Mahammad Amin Rasulzade

Mahammad Amin Rasulzade | |

|---|---|

Məhəmməd Əmin Rəsulzadə | |

Rasulzade c. 1950 | |

| President of Azerbaijani National Council | |

| In office 27 May 1918 – 7 December 1918 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 January 1884 Novkhany, Baku uezd, Baku Governorate, Caucasus Viceroyalty, Russian Empire (now Azerbaijan) |

| Died | 6 March 1955 (aged 71) Ankara, Turkey |

| Resting place | Cebeci Asri Cemetery |

| Political party | Musavat Party Democrat Party[1] |

| Spouse | Umbulbanu Rasulzade |

| Profession | The Leader of Azerbaijan |

| Signature | |

Mahammad Amin Akhund Haji Molla Alakbar oghlu Rasulzade[a] (31 January 1884 – 6 March 1955) was an Azerbaijani politician, journalist and the head of the Azerbaijani National Council. He is mainly considered the founder of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918 and the father of its statehood. His expression "Bir kərə yüksələn bayraq, bir daha enməz!" ("The flag once raised shall never fall!") became the motto of the independence movement in Azerbaijan in the early 20th century.

Early life

[edit]

Born on 31 January 1884 to Akhund Haji Molla Alakbar Rasulzadeh in Novkhany,[2] near Baku, Mahammad Amin Rasulzade received his education at the Russian-Muslim Secondary School and then at the Technical College in Baku. In his years of study he created "Muslim Youth Organisation Musavat",[3] first secret organisation in Azerbaijan's contemporary history, and beginning from 1903 Rasulzade began writing articles in various opposition newspapers and magazines. At that time, his anti-monarchist platform and his demands for the national autonomy of Azerbaijan, aligned him with Social Democrats and future Communists. In 1904 he founded the first Muslim social-democrat organisation "Hummet" and became editor-in-chief of its newspapers, Takamul (1906–1907) and Yoldash (1907). Rasulzade also published many articles in non-partisan newspapers such as Hayat, Irshad, and the journal Fuyuzat. His dramatic play titled The Lights in the Darkness was staged in Baku in 1908.

Rasulzade and his co-workers were representatives of the Azerbaijani intelligentsia. Most of them, including Rasulzade himself, had been members of the Baku organization of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers' Party (Bolsheviks) in 1905.[4] A photograph is extant in Soviet archives, showing Rasulzade with Prokopius Dzhaparidze and Meshadi Azizbekov, Bolsheviks who later became famous as two of the 26 Baku Commissars shot during the civil war.[5] During the First Russian Revolution (1905–1907), Rasulzade actively participated in revolutionary developments. As the story goes, it was Rasulzade who saved young Joseph Stalin in 1905 in Baku, when police were searching for the latter as an active instigator of riots.[6]

In 1909, under the persecution from Tsarist authorities, Rasulzade fled Baku to participate in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911. While in Iran, Rasulzade edited Iran-e Azad newspaper,[7] became one of the founders of Democrat Party of Persia and began publishing its newspaper Iran-e Now[8] which means "New Iran" and which has been described as "the greatest, most important and best known of the Persian newspapers, and the first to appear in the large size usual in Europe".[9] In 1911, Rasulzade also published his book "Saadet-e bashar" ("Happiness of Mankind") in defense of the revolution. Rasulzade was fluent in Persian.[10]

After Russian troops entered Iran in 1911 and, in cooperation with British, assisted Qajar Court to put an end to Iranian Constitutional Revolution, Rasulzade fled to Istanbul, then capital of Ottoman Empire. Here, in the wake of Young Turk Revolution, Rasulzade founded a journal called Türk Yurdu (The Land of Turks), in which he published his famous article "İran Türkleri" about the Iranian Turks.[11]

The Musavat Party and Azerbaijan Democratic Republic

[edit]

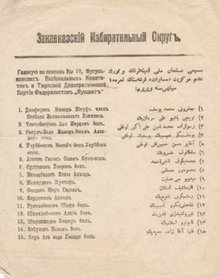

After the Amnesty Act of 1913, dedicated to the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty, Rasulzade returned to Baku, left the Hummet party he was previously member of, and joined the then secret Musavat (Equality) party in 1913, established in 1911, which initially promoted pan-Islamist, pan-Turkist and Socialist ideas,[12][13][14][15][16] or more precisely Pan-Islamism yet with affinity for greater cultural bonds with the Turkic world,[17] and which eventually became Azerbaijani nationalist party, and quickly became its chief. In 1915 he started to publish the party's newspaper "Açıq Söz" (Open word) which lasted until 1918. When the February Revolution happened, Musavat together with other secret political parties in the Russian Empire, were quickly legalized and became a leading party of Caucasian Muslims after it merged with Party of Turkic Federalists headed by Nasib Yusifbeyli. The October Revolution in 1917 lead to the secession of Transcaucasia from Russia and Rasulzade became head of Muslim faction in the Seym, the parliament of the Transcaucasian Federation. After the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Federation, the Muslim faction re-organized into the Azerbaijani National Council, whose head Rasulzade was unanimously elected in May 1918.

On 28 May 1918 the Azerbaijani National Council, headed by Rasulzade, declared an independent Azerbaijan Republic. Rasulzade also initiated the establishment of Baku State University together with Rashid Khan Gaplanov, minister of education with the funding of oil baron Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev in 1919. Rasulzade taught Ottoman literature at the university.

Bir kərə yüksələn bayraq, bir daha enməz! The flag once raised will never fall!

— Mahammad Amin Rasulzade

After the collapse of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in April 1920, Rasulzade left Baku and went into hiding in the mountainous village of Lahıc, Ismailli to direct the resistance to Sovietization. But in August 1920, after the Soviet Russian army crushed the rebellions of Ganja, Karabakh, Zagatala and Lankaran, led by ex-officers of the Azerbaijani National Army, Rasulzade was arrested and brought to Baku. It was only due to an earlier rescue of Joseph Stalin, as Rasulzade hid Stalin from the police, that Rasulzade was released and transferred from Azerbaijan to Russia.[18] For the next two years, Rasulzade worked as the press representative at the Commissariat on Nations in Moscow. He was seconded to Saint Petersburg in 1922 from where he escaped to Finland.

Exile

[edit]For the rest of his life, Rasulzade lived in exile first in Turkey. Between 1923 and 1927, he was an editor-in-chief of the magazine called Yeni Kafkasya (Turkish: New Caucasus)[19] which was suspended by the Kemalist government by the request of Moscow. Rasulzade continued to publish various articles, newspapers, and magazines from 1928 until 1931 in Turkey.[20] However, the 1931 suppression of the emigre publications[citation needed] coincided with Rasulzade's expulsion from Turkey, and some saw it as the result of caving in to Soviet pressure.[citation needed] In exile Rasulzade published a pamphlet titled O Pantiurkizme v sviazi s kavkazskoi problemoi (О Пантюркизме в связи с кавказской проблемой, Pan-Turkism with regard to the Caucasian problem), in which he firmly stated his view: Pan-Turkism was a cultural movement rather than a political program.[21] Thus, he went to Poland in 1938, where he met his wife, Wanda, niece of Polish statesman Józef Piłsudski, then to Romania in 1940.[citation needed]

During his exile in 1942, Rasulzade was contacted by the leadership of Nazi Germany, who, when forming national legions from representatives of the peoples of the Soviet Union, relied on well-known and authoritative representatives, such as Rasulzade and other leaders of the 1918 Caucasian republics.[22] Hitler tried to recruit Rasulzade as a leader of a German-occupied Caucasus.[23] Rasulzade was convinced of the close connection between Musavatism and Nazism. He noted that the social program of the Musavat party was of a national socialist nature.[24] During a meeting with the German leadership in May 1942, Rasulzade attempted to form a strategic alliance with Nazi Germany in order to restore Azerbaijan's independence.[25] Rasulzade demanded that Nazi Germany announce its absolute commitment to the restoration of the Transcaucasian states, however, due to the evasive nature of the Reich in the conversation, he left Berlin.[26]

Finally, after World War II, he went back to Ankara, Turkey in 1947, where he participated in the politics of the marginal Pan Turkic movement.[27] Due to sensitivity of his presence in either Turkey or Iran, and being often exiled, Rasulzade "cherished bad memories of both Iran and Turkey".[28] In his appeal to Azerbaijani people in 1953 through Voice of America, he stressed his hope that one day it will become independent again.[29] He died in 1955, a broken man according to Thomas Goltz,[27] and was buried in Cebeci Asri cemetery in Ankara.[18]

Legacy and honors

[edit]

Rasulzade was commemorated by many memorials throughout Azerbaijan, such as Baku State University, which was named after his honor. Rasulzade was depicted on the obverse of the Azerbaijani 1000 manat banknote of 1993–2006.[30]

The Mehmet Emin Resulzade Anatolian High School was named after him and is a public high school at Ankara, Turkey.[31]

Major works

[edit]Rasulzade's works include:[3][32]

- The critic of the party of Etedaliyun (Persian: تنقید فرقه اعتدالیون، و یا، اجتماعیون - اعتدالیون, romanized: Tanqid-e firqa-ye-Etedālīyūn va ya, Ejtemāīyūn-e etedālīyūn). Teheran, 1910 (in Persian);

- The happiness of the mankind (Persian: سعادت بشر, romanized: Saadet-e basher). Ardebil, 1911 (in Persian);

- Two views on the form of government (together with Ahmet Salikov). Baku, 1917 (in Azerbaijani);

- Democracy. Baku, 1917 (in Azerbaijani);

- Which government is good for us? Baku, 1917 (in Azerbaijani);

- Role of Musavat in the formation of Azerbaijan. Baku, 1920 (in Azerbaijani);

- Azerbaijan Republic: characteristics, formation and contemporary state. Istanbul, 1923 (in Ottoman Turkish);

- Siyavush of our century. Istanbul, 1923 and second edition in 1925 (in Ottoman Turkish);

- Ideal of liberty and youth. Istanbul, 1925 (in Ottoman Turkish);

- Political Situation in Russia. Istanbul, 1925 (in Ottoman Turkish);

- The collapse of revolutionary socialism and the future of democracy. Istanbul, 1928 (in Ottoman Turkish);

- Nationality and Bolshevism. Istanbul, 1928 (in Ottoman Turkish);

- Panturanism in regard with the Caucasian problem. Paris, 1930 (in Russian; reprinted with an English introduction in 1985 in Oxford);

- Azerbaijan's struggle for independence. Paris, 1930 (in French);

- Shefibeycilik. Istanbul, 1934 (in Turkish);

- Contemporary Azerbaijani literature. Berlin, 1936 (in Turkish);

- Contemporary Azerbaijani literature. Berlin, 1936 (in Russian);

- The problem of Azerbaijan. Berlin, 1938 (in German);

- Azerbaijan's struggle for independence. Warsaw, 1938 (in Polish)

- Azerbaijan's cultural traditions. Ankara, 1949 (in Turkish);

- Contemporary Azerbaijani literature. Ankara, 1950 (in Turkish);

- Contemporary Azerbaijani history. Ankara, 1951 (in Turkish);

- Great Azerbaijani poet Nizami. Ankara, 1951 (in Turkish);

- National Awareness. Ankara. 1978 (in Turkish);

- Siyavush of our century. Ankara, 1989 (in Turkish);

- Iranian Turks. Istanbul, 1993 (in Turkish);

- Caucasian Turks. Istanbul, 1993 (in Turkish).

Notes

[edit]- ^

- Azerbaijani: محمد امین آخوند حاجی ملا علی اکبر اوغلی رسولزاده, Məhəmməd Əmin Axund Hacı Molla Ələkbər oğlu Rəsulzadə, IPA: [mæhæmˈmæd æˈmin ɾæsulzɑːˈdæ]

- Turkish: Mehmet Emin Ahund Hacı Molla Alekber oğlu Resulzâde

- Russian: Мамед Эмин Ахунд Гаджи Молла Алекбер оглы Расулзаде, romanized: Mamed Emin Akhund Gadzhi Molla Alekber ogly Rasulzade

References

[edit]- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 103. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- ^ Gümüşsoy, Emine (2007). "Mehmed Emin Resulzâde and a Nationalist Journal: Azeri Turk". Kahramanmaraş Sütçüimam University Journal of Social Sciences (in Turkish). 4 (1–2). Kahramanmaraş Sütçüimam University: 45–56 – via DergiPark.

Mehmed Emin Resulzâde 31 Ocak 1884'de Bakü'nün Novhanı köyünde dünyaya gelmiştir. Babası Ahund Hacı Molla Alekber Resulzâde, annesi Zal kızı Ziynet'tir.

- ^ a b "Memmed Amin Resûlzâde (Bakû/Novhanı, 31 Ocak 1884 - Ankara, 6 Mart 1955)" (PDF). Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Turkey. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2021. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ Firuz Kazemzadeh (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia. New York Philosophical Library. p. 21. ISBN 0-8305-0076-6. OCLC 1943521.

- ^ M.D. Guseinov. Тюркская Демократическая Партия Федералистов "Мусават" в прошлом и настоящем. Baku, 1927, p. 9

- ^ Rais Rasulzade (his grandson), "Mahammad Amin Rasulzade: Founding Father of the First Republic," Archived 2011-12-08 at the Wayback Machine in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 7:3 (Autumn 1999), pp. 22-23.

- ^ J. Castagne. "Le Bolshevisme et l'Islam". Revue du Monde Mussulman. 51 (1). Paris: 245–246.

- ^ Mammed Amin Rasulzade (1992). "Rasulzade's letter to Tereqqi newspaper's 16 August 1909 issue". Works, Volume I. Baku.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nassereddin Parvin (2012-03-30). "IRĀN-E NOW". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. pp. 498–500. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- ^ Gasimov, Zaur (2022). "Observing Iran from Baku: Iranian Studies in Soviet and Post-Soviet Azerbaijan". Iranian Studies. 55 (1): 40. doi:10.1080/00210862.2020.1865136. S2CID 233889871.

- ^ Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Azerbaijan Government 1918-1920. Baku, "Youth", 1990. page 25 lines 3-11 from above

- ^ Pan-Turkism: From Irrendentism to Cooperation by Jacob M. Landau P.55

- ^ On the Religious Frontier: Tsarist Russia and Islam in the Caucasus by Firouzeh Mostashari P. 144

- ^ Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires by Aviel Roshwald, page 100

- ^ Disaster and Development: The politics of Humanitarian Aid by Neil Middleton and Phil O'keefe P. 132

- ^ The Armenian-Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications by Michael P. Croissant P. 14

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski, Russian and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition, Columbia University Press, 1995, p. 52.

- ^ a b Smele, Jonathan D. (2015-11-19). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 920. ISBN 9781442252813.

- ^ Zaur Gasimov (Fall 2012). "Anti-communism Imported? Azeri Emigrant Periodicals in Istanbul and Ankara (1920-1950s)". Cumhuriyet Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi. 8 (16): 9.

- ^ Məhəmməd Əmin Rəsulzadə Ensklopediyası. 194.

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski (1995). Russian and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-231-07068-3.

- ^ Thomas de Waal (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 278. ISBN 9780199350704.

- ^ Simon Sebag Montefiore (2009). Young Stalin. New York: Random House. p. 575. ISBN 9780307498922.

where Hitler tried to recruit him as a leader of a German-sponsored Caucasus

- ^ Schnelle, Johannes (2020). Gorsky, Anton [in Russian] (ed.). ""Враг моего врага": деятельность азербайджанской партии "Мусават" в Германии (1933-1939)" ["The enemy of my enemy": the activities of the Azerbaijani party "Musavat" in Germany (1933-1939)]. Istorichesky Vestnik (in Russian). 32. St. Petersburg: 84–111. doi:10.35549/HR.2020.2020.32.005. ISSN 2411-1511. S2CID 225281245.

- ^ Kucera, Joshua (May 21, 2020). "Armenia, Azerbaijan trade Nazi collaboration accusations". Eurasianet. New York: Harriman Institute. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

Rasulzade was later exiled when the Soviet Union took over Azerbaijan, and during World War II briefly tried to enlist Nazi Germany in a tactical alliance to restore Azerbaijan's independence

- ^ Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-231-07068-3.

- ^ a b Goltz, Thomas (1998). Azerbaijan diary : a rogue reporter's adventures in an oil-rich, war-torn, post-Soviet republic. M.E. Sharpe. p. 18. ISBN 0-7656-0243-1.

- ^ Charles van der Leeuw, Azerbaijan: A Quest for Identity, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 121.

- ^ http://www.rasulzade.org/ME_Rasulzade_nin_Amerikanin_Sesinde_chixishi.mp3[permanent dead link]

- ^ National Bank of Azerbaijan Archived 2009-04-14 at the Wayback Machine. National currency: 1000 manat Archived 28 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ "T.C. Millî Eğiim Bakanlığı". www.meb.gov.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ "Məhəmməd Əmin Rəsulzadə (1884 Bakı - 1955 Ankara)". Retrieved 2007-04-02.[permanent dead link]

Further reading

[edit]- Balayev, Aydin (2015). "Mamed Emin Rasulzadeh and the establishment of the Azerbaijani state and nation in the early twentieth century". Caucasus Survey. 3 (2): 136–149. doi:10.1080/23761199.2015.1045292. S2CID 142581341.

External links

[edit]- Leader's Page Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Mahammad Amin Rasualzade Website

- Speech by Rasulzadeh[permanent dead link]

- "Mahammad Amin Rasulzade, Founding Father of the First Republic," by grandson Rais Rasulzade, Azerbaijan International, Vol. 7:3 (Autumn 1999), pp. 22–23.

- "Mahammad Amin Rasulzade, Statesman, Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan Leaders" (1918–1920), in Azerbaijan International, Vol 6:1 (Spring 1998), pp. 26–30.

- Azerbaijani-language writers

- 1884 births

- 1955 deaths

- People from Absheron District

- Russian Constituent Assembly members

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic politicians

- Musavat politicians

- Azerbaijani anti-communists

- People of the Persian Constitutional Revolution

- Azerbaijani exiles

- Azerbaijani emigrants to Iran

- Azerbaijani emigrants to Turkey

- Burials at Cebeci Asri Cemetery

- Azerbaijani nationalists

- Pan-Turkists

- Democrat Party (Persia) politicians

- Azerbaijani independence activists

- 20th-century Persian-language writers

- Azerbaijani Persian-language writers

- Azerbaijani collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Muslims from the Russian Empire

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Iran