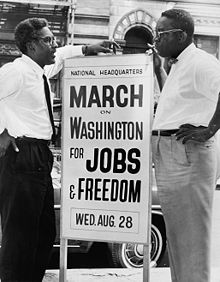

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (or "The Great March on Washington", as styled in a sound recording released after the event)[1][2] was one of the largest political rallies for human rights in United States history[3] and called for civil and economic rights for African Americans. It took place in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King, Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech advocating racial harmony during the march.[4]

The march was organized by a group of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations,[5] under the theme "jobs, and freedom".[3] Estimates of the number of participants varied from 200,000 to 300,000.[6] Observers estimated that 75–80% of the marchers were black and the rest were white and non-black minorities.

The march is widely credited with helping to pass the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965).

Background and Organization

The march was planned and initiated by A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, president of the Negro American Labor Council,[6] and vice president of the AFL-CIO. Randolph had planned a similar march in 1941. The threat of the earlier march had convinced President Roosevelt to establish the Committee on Fair Employment Practice and ban discriminatory hiring in the defense industry.

The 1963 march was an important part of the rapidly expanding Civil Rights Movement. It also marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln.

In the political sense, the march was organized by a coalition of organizations and their leaders including: Randolph who was chosen as the titular head of the march, James Farmer (president of the Congress of Racial Equality), John Lewis (chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), Martin Luther King, Jr. (president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference),[6] Roy Wilkins (president of the NAACP),[6] Whitney Young (president of the National Urban League).

The mobilization and logistics of the actual march itself was administered by deputy director Bayard Rustin, a civil rights veteran and organizer of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first of the Freedom Rides to test the Supreme Court ruling that banned racial discrimination in interstate travel. Rustin was a long-time associate of both Randolph and Dr. King. With Randolph concentrating on building the march's political coalition, Rustin built and led the team of two hundred activists and organizers who publicized the march and recruited the marchers, coordinated the buses and trains, provided the marshals, and set up and administered all of the logistic details of a mass march in the nation's capital.[7]

The march was not universally supported among civil rights activists. Some, including Rustin (who assembled 4,000 volunteer marshals from New York), were concerned that it might turn violent, which could undermine pending legislation and damage the international image of the movement.[8] The march was condemned by Malcolm X, spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, who termed it the "farce on Washington".[9]

March organizers themselves disagreed over the purpose of the march. The NAACP and Urban League saw it as a gesture of support for a civil rights bill that had been introduced by the Kennedy Administration. Randolph, King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) saw it as a way of raising both civil rights and economic issues to national attention beyond the Kennedy bill. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) saw it as a way of challenging and condemning the Kennedy administration's inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans.[5]

The March

On August 28, more than 2,000 buses, 21 chartered trains, 10 chartered airliners, and uncounted cars converged on Washington.[10] All regularly scheduled planes, trains, and buses were also filled to capacity.[5]

The march began at the Washington Monument and ended at the Lincoln Memorial with a program of music and speakers. The march failed to start on time because its leaders were meeting with members of Congress. To the leaders' surprise, the assembled group began to march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial without them.

The 1963 March also spurred anniversary marches that occur every five years, hi with the 20th and 25th being some of the most well known. The 25th Anniversary theme was "We Still have a Dream...Jobs*Peace*Freedom."

Speakers

Representatives from each of the sponsoring organizations addressed the crowd from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial. Speakers included all six civil-rights leaders of the so-called, "Big Six"; Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish religious leaders; and labor leader Walter Reuther. None of the official speeches were by women; Josephine Baker gave a speech during the preliminary offerings, but women's presence in the official program was limited to a "tribute" led by Bayard Rustin (planned to be Myrlie Evers, who was unable to attend due to a prior commitment in Boston).

Floyd McKissick read James Farmer's speech because Farmer had been arrested during a protest in Louisiana; Farmer had written that the protests would not stop "until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the North."[11]

Official program

Marian Anderson was scheduled to lead the National Anthem but was unable to arrive on time; Camilla Williams performed in her place. Following an invocation by Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director A. Philip Randolph, followed by Eugene Carson Blake. A tribute to "Negro Women Fighters for Freedom" was then led by Bayard Rustin (substituting for the absent Myrlie Evers), who introduced Daisy Bates, Diane Nash, Prince E. Lee, Rosa Parks, and Gloria Richardson. The following speakers were SNCC chairman John Lewis, labor leader Walter Reuther and CORE chairman Floyd McKissick (substituting for arrested CORE director James Farmer). The Eva Jessye Choir then sang, and Rabbi Uri Miller (president of the Synagogue Council of America) offered a prayer, followed by National Urban League director Whitney Young, NCCIJ director Mathew Ahmann, and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins. After a performance by singer Mahalia Jackson, American Jewish Congress president Joachim Prinz spoke, followed by SCLC president Martin Luther King, Jr. Rustin then read the march's official demands for the crowd's approval, and Randolph led the crowd in a pledge to continue working for the march's goals. The program was closed with a benediction by Morehouse College president Benjamin Mays.

Controversy over John Lewis' speech

Although one of the officially stated purposes of the march was to support the civil rights bill introduced by the Kennedy Administration, several of the speakers criticized the proposed law as insufficient.

John Lewis of SNCC was the youngest speaker at the event.[12] His speech—which a number of SNCC activists had helped write—took the Administration to task for how little it had done to protect southern blacks and civil rights workers under attack in the Deep South.[9][13] Cut from his original speech at the insistence of more conservative and pro-Kennedy leaders[5][14] were phrases such as:

In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the administration's civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late. ...

I want to know, which side is the federal government on?...

The revolution is a serious one. Mr. Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the streets and put it into the courts. Listen, Mr. Kennedy. Listen, Mr. Congressman. Listen, fellow citizens. The black masses are on the march for jobs and freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won't be a "cooling-off" period.

...We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently...

Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and even SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of his speech.[15]

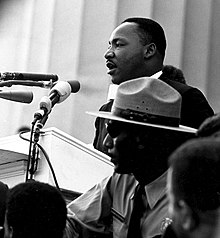

Martin Luther King, Jr.'s speech

The speech given by SCLC president King, who spoke last, became known as the "I Have a Dream" speech, which was carried live by TV stations and subsequently considered the most impressive moment of the march. Over time it has been hailed as a masterpiece of rhetoric, added to the National Recording Registry and memorialized by the National Park Service with an inscription on the spot where King stood to deliver the speech.

Singers

Gospel legend Mahalia Jackson sang "How I Got Over", musician Bob Dylan performed several songs, including "Only a Pawn in Their Game", about the culturally fed racial hatred amongst Southern whites that led to the assassination of Medgar Evers; and "When the Ship Comes In", during which he was joined by fellow folk singer Joan Baez, who earlier had led the crowds in several verses of "We Shall Overcome" and "Oh Freedom". Peter, Paul and Mary sang "If I Had a Hammer" and Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind". Marian Anderson sang at the march as well.

Media coverage

Media attention gave the march national exposure, carrying the organizers' speeches and offering their own commentary. In his section The March on Washington and Television News, William Thomas notes: "Over five hundred cameramen, technicians, and correspondents from the major networks were set to cover the event. More cameras would be set up than had filmed the last Presidential inauguration. One camera was positioned high in the Washington Monument, to give dramatic vistas of the marchers".[16]

Criticism

Black nationalist Malcolm X, in his Message to the Grass Roots speech, criticized the march, describing it as "a picnic" and "a circus". He said the civil rights leaders had diluted the original purpose of the march, which had been to show the strength and anger of black people, by allowing white people and organizations to help plan and participate in the march.[17]

See also

References

- Footnotes

- ^ Ward, Brian (April 1998). "Recording the Dream". History Today.

Yet by the end of the year the company was promoting its Great March to Washington album, featuring `I Have A Dream' in its entirety.

- ^ King III, Martin Luther (2010-08-25). "Still striving for MLK's dream in the 21st century". The Washington Post. Washington, DC. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ^ a b Bayard Rustin Papers (1963-08-28), March on Washington (Program), National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved 2013-05-21

- ^ Suarez, Ray (2003-08-28). "Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" Remembered". PBS NewsHour. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

{{cite episode}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d "March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom". Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement.

- ^ a b c d "Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Mathew Ahmann, Executive Director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice, in a Crowd". World Digital Library. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Branch 1988, p. 872.

- ^ Branch 1988, p. 871.

- ^ a b Branch 1988, p. 874.

- ^ Branch 1988, p. 876.

- ^ Current biography yearbook. H. W. Wilson Company. 1965. p. 121.

- ^ Doak, Robin Santos (2007). The March on Washington: Uniting Against Racism. Capstone. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7565-3339-7. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Full Text of John Lewis' Speech ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ Lewis, John (1998). Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0156007088.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Carson, Clayborne (1981). In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Harvard University Press.

- ^ "The March on Washington and Television News," by William Thomas

- ^ Malcolm X (1990) [1965]. Malcolm X Speaks. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. pp. 14–17. ISBN 0-8021-3213-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Bibliography

- Branch, Taylor (1988). Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63. New York; London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671687427.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leonard Freed, This Is the Day: The March on Washington, Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2013; ISBN 978-1-60606-121-3.

- Marable, Manning (2002). Freedom: A Photographic History of the African American Struggle. Phaidon Press. ISBN 9780714845173.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Tuttle, Kate (1999). "March on Washington, 1963". Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 9780465000715.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Williams, Juan (1987). Eyes on the prize: America's civil rights years, 1954-1965. New York, NY: Viking. ISBN 9780245546686.

External links

- The short film "The March on Washington (1963)" is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The March, 1963, from the National Archives YouTube Channel

- Eyes on the Prize March on Washington video page, PBS, retrieved 2010-09-19

- March on Washington – King Encyclopedia, Stanford University

- March on Washington August 28, 1963 ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- March on Washington, WDAS History

- The 1963 March on Washington - slideshow by Life magazine

- Original Program for the March on Washington

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech at the March