Communist Party USA

The Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) is one of several Marxist-Leninist groups in the United States. For many years (1959-2000) it was led by Gus Hall. Perhaps the most famous ex-member of the CPUSA is Angela Davis. The current leader of the party is Sam Webb.

Formation and early history

In January, 1919, Lenin invited the left wing of the Socialist Party to join the Communist International. During the spring of 1919 the left wing of the Socialist Party, buoyed by a large influx of new members from countries involved in the Russian Revolution, prepared to wrest control from the smaller controlling faction of moderate socialists. A referendum to join the Comintern passed with 90% support but the results were suppressed by the incumbent leadership. Elections for the party's National Executive Committee resulted in 12 leftists being elected out of a total of 15. Calls were made to expel moderates from the party. The moderate incumbents struck back by expelling several state organizations, half a dozen language federations, and many locals, in all two thirds of the membership. They then called an emergency convention which was held in Chicago on August 30, 1919. Plans were made by the left wing to continue to gain control of the party at a June conference, the National Conference of the Left Wing, but the language federations, independent socialist organizations from areas involved in the Russian Revolution, eventually joined by Charles Ruthenberg and Louis Fraina broke away from that effort and determined to form their own party, forming the Communist Party of America on September 2, 1919 at a separate convention in Chicago. Meanwhile plans led by John Reed and Benjamin Gitlow to crash the Socialist Party convention went ahead. It was planned that delegations from the portions of the party which had been expelled would arrive early and demand participation. Tipped off, the incumbents dealt with that maneuver by calling the police who obligingly expelled the leftists from the hall. The remaining leftist delegates walked out and meeting with the expelled delegates formed the Communist Labor Party on September 1, 1919. Under pressure from the Communist International, these two communist parties officially merged at a conference in Woodstock, New York in May, 1921. Only 10% of the members of the newly formed party were fluent in English.

The Red Scare

From its inception, the Communist Party USA came under attack from state and federal governments and later the FBI. Initially there was a strong reaction in the United States to the Russian Revolution and associated events in Germany and Hungary. This led to the Palmer Raids or Red Scare in late 1919 and January, 1920 when Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer acting under the Sedition Act of 1918 arrested many thousand party members. Although some were released, many were deported to their countries of origin which were now embroiled in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution.

The underground party

Consequently, the Communist Party was forced underground and went through name changes to evade the authorities. Following the recruitment of, the Workers Council — another factional grouping coming out of the Socialist Party — the aboveground front for the illegal Communist Party gradually replaced the underground party. Despite a struggle by some party members to retain an illegal appartus on principle, the aboveground and underground parties were fully merged, the new party being officially named the Worker (Communist) Party. Significantly, the party also recruited an organisation of African-American socialists called the African Blood Brotherhood, some of the members of which would later be important to communist work among Black people.

The legal party

Having emerged into legality the party developed a number of more or less fixed factional groupings within its leadership. Firstly there was the faction around the party's Chairman Charles Ruthenberg which was largely organised by his supporter Jay Lovestone. Opposing this faction was the Foster-Cannon caucus which was headed by the party's specialist in trade union questions William Z. Foster, who was the head of the Trade Union Unity League, and James P. Cannon, who led the International Labor Defense organisation. The base of the first faction being concentrated on the party's foreign language federations while the latter found support among 'native' workers.

Early factional struggles

In 1925 Charles Ruthenberg and William Z. Foster led mutually hostile factions within the party. Comintern representative Sergei Gusev ordered the majority Foster faction to surrender control to Ruthenberg's faction.; Foster complied.

Ruthenberg died in 1927 and his ally, Jay Lovestone, succeeded him as party secretary. The party's status as a section of the Comintern ensured that factional struggles in the leading party of the Comintern, the ruling Russian section, would impact on the Communist Party in America. Therefore the attendance of party members at the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928 was certain to have repercussions. Repercussions which would surprise especially those who sought to utilise their connections to leading circles in the Comintern to their advantage in the American party such as Cannon and Lovestone.

Following the lead of the Comintern

As a section of the Communist International (“Comintern”), the Communist Party closely adhered to the decisions of that body, as it was bound to do by virtue of its affiliation. Therefore, when he attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern, Cannon sought to gain advantage for his joint faction with Foster in their power struggle against the former Ruthenberg faction now led by Lovestone. Cannon was later to describe himself in retrospect as a "well trained factional hooligan" and was not committed in any way to Trotskyism and had in his documents included statements derogatory to Trotsky. However he and Maurice Spector of the Communist Party of Canada were accidentally issued a copy of Trotsky's "Critique of the Draft Program of the Comintern" that they were instructed to read and return. Persuaded by its contents, they came to an agreement to return to America and campaign for the document's positions. A copy of the document was then smuggled out of the country in a child's toy.

Back in America, Cannon and his close associates in the ILD such as Max Shachtman and Martin Abern, dubbed the three generals without an army, began to organise support for Trotsky's theses. However, as this attempt to develop a Left Opposition came to light, they were threatened with expulsion from the party. After a short struggle in which they were ruthlessly opposed by Lovestone, the party's national secretary, they were expelled and their supporters purged along with them. They were left with very few supporters, although groups won to their positions were to be expelled from the party for years to come. They organised the Communist League of America as a section of Trotsky's International Left Opposition.

At the same Congress, Lovestone had impressed the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as a strong supporter of Nikolai Bukharin the general secretary of the Comintern. This was to have devestating consequences for Lovestone when, in 1929, Bukharin was on the losing end of a struggle with Stalin and was purged from his position on the Politburo as well as removed as head of the Comintern.

In a reversal of the events of 1925, a Comintern delegation was sent to the United States and demanded that Lovestone resign as party secretary in favour of his arch-rival Foster, despite the fact that Lovestone enjoyed the support of the vast majority of the American party's membership. Lovestone traveled to the Soviet Union and appealed directly to the Comintern. Stalin informed Lovestone that he "had a majority because the American Communist Party until now regarded you as the determined supporters of the Communist International. And it was only because the Party regarded you as friends of the Comintern that you had a majority in the ranks of the American Communist Party".

When Lovestone returned to the United States, he and his ally Benjamin Gitlow were purged despite holding the leadership of the party. Ostensibly, this was not due to Lovestone's insubordination in challenging a decision by Stalin to his face but for his support of the thesis of American Exceptionalism, an argument they used to assert that socialism could be achieved peacefully in the USA and which contradicted the new Third Period position that Stalin and the Comintern were trying to persuade Communist parties to adopt. This position was seen as symptomatic of Lovestone's "Bukharinism" and his support for the Right Opposition.

They too formed their own group called the Communist Party (Opposition), a section of the pro-Bukharin International Communist Opposition which was initially larger than the Trotskyists but failed to survive past 1941. Lovestone had initially called his faction the Communist Party (Majority Group) in the expectation that the majority of the CPUSA's members would join him, but only a few hundred people joined Lovestone's new organization.

See also External link to Stalin's comments. and Exceptionalism

Union organizing and other progressive work

Following the disputes described above a new party leadership was installed headed by Earl Browder formerly a subordinate of William Foster. It has been speculated that Foster himself was passed over for various reasons but his ill health in this period undoubtedly played a role. The first part of Browder's leadership coincided with the so called Third Period of renewed revolutionary offensive as the period after 1928 was described by the Comintern. This Third Period meant that other left wingers were described by the communists as being social-fascists and any alliance with them was therefore rejected.

In the depths of the Great Depression, which the Third Period ran in parallel with, this led the CP to attempt to launch new unions unconnected to the older unions affiliated to the American Federation of Labor. This policy of dual unions had however previously been decisively opposed by the CP as adventurist and ultra-left. Although the new unions were grouped in the Foster led Trade Union Education League now renamed the Trade Union Unity League, Foster himself was ill through most of this period and took little part in the work. None of the unions formed amounted to very much numerically although many helped to form cadre who were later to take part in the great upsurge of the 1930s.

By 1932 the worst excesses of the Third Period and the Great Depression were somewhat lessened and with the election of Roosevelt union organising began an upsurge. Initially this saw new union members drafted into 'federal' union locals by the AFL, which soon proved to be a failure. Therefore the strategy of the United Mine Workers, led by John L. Lewis, to unionise those basic industries related to their own received great support both from rank and file unionists and the new Committee of Industrial Organizations. Many of these new unions such as the Steel Workers Organising Committee and, most importantly, the United Auto Workers hired communists as local organisers largely due to the work they had been doing for years previously. In addition the CP dissolved its own small dual unions into the new CIO affiliated unions thus the Auto Workers Union was wound up with its members joing the UAW.

In addition to the industries and unions named above communists were important to union organising drives in rubber, longshore and among garment workers. Even farm workers were organised by party members and the membership of the party grew considerably. Communists organized the unemployed and fought successfully for unemployment insurance and what eventually became social security. They fought against evictions and housing repossessions. The CPUSA was the only political party at that time that explicitly denounced racism and fought for reforms in that area of US social life.

Key to this turn was the rejection by the Comintern of the Third Period and the adoption of the Popular Front policy which in America meant that the party sought unity with forces to its right. Earl Browder offered to run as Norman Thomas' running mate on a joint Socialist Party-Communist Party ticket in the 1936 presidential election but Thomas rejected this overture.

The Popular Front policy not only meant attempts to cooperate with the Socialists, who had previously been fiercely denounced as "social fascists', but also with liberals and even the Democratic Party. Indeed while standing its own candidates for office the CPUSA pursued a policy of representing the Democratic Party as the lesser evil in elections. Intellectually the Popular Front period saw the development of a strong communist influence in intellectual and artistic life. This was often through various party influenced or controlled organisations or, as they were pejoratively known, "fronts."

It was during the Popular Front period that party members rallied to the defence of the Spanish Republic after a fascist military uprising tried to overthrow it resulting in the Spanish Civil War (1936 to 1939). Throughout the world, leftists rallied to the defence of the Spanish Republic, raising funds for medical relief and, in many cases, volunteering to fight for the Republic. The CPUSA was no exception to this phenomenon. Many of its members made their way to Spain with the aid of the party to join the Lincoln Brigade, one of the International Brigades consisting of American citizens. Among its other achievements, the Lincoln Brigade was the first American military force to include blacks and whites integrated on an equal basis.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

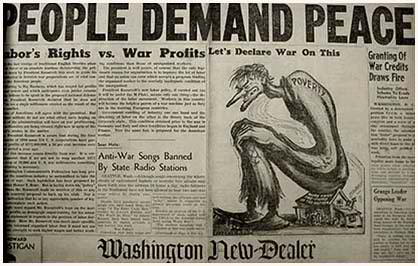

The Washington Commonwealth Federation newspaper after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact

The CPUSA was adamantly opposed to fascism during the Popular Front period. In fact, the Popular Front was motivated by a fear of fascism, and the possible threat to the Soviet Union that Nazi Germany posed. The signing of a non-aggression pact with Hitler (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) in 1939 meant that the CPUSA turned its focus from anti-fascism to advocacy of peace. The CPUSA even went so far as to accuse Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt of provoking aggression against Hitler. The CPUSA went so far as to denounce the Polish government as fascist after the German and Soviet invasion. In loyal, indeed abject, allegiance to Russia this policy was again changed after the Soviet Union was attacked with the launch of Operation Barbarossa on June 22,1941. So sudden was this change that CPUSA members of the UAW negotiating on behalf of the union literally changed their position from being in favour of strike action to opposing it in the same negotiating session.

Throughout World War Two, the CPUSA went from pursuing a policy of militant, if bureaucratic, trade unionism to opposing strike actions at all costs. In fact the leadership of the CPUSA were among the most patriotic elements during these years advocating the No Strike Pledge and social peace. It seems that Earl Browder actually anticipated a prolonged period of social harmony after the war: in order to better integrate the communist movement into American life the party was officially dissolved in 1944 and replaced by a Communist Political Association. After the war, however, the international communist movement swung to the left. Browder found himself isolated when a critical letter from the leader of the French Communist Party received wide circulation. As a result of this, he was retired and replaced by William Z. Foster, who would remain the senior leader of the party until his own retirement in 1958.

With the end of the war, the CPUSA was reformed under Foster's leadership. In line with other communist parties world wide, the CPUSA also swung to the left and as a result of this experienced a brief period in which a number of internal critics argued for a more leftist stance than the leadership was willing to countenance. The result of this was the expulsion of some handfuls of "premature anti-revisionists." Few of these were recruited to the Trotskyist movement, although this might have seemed the logical destination for them. William Dunne, Foster's former close ally, and brother of three leading members of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, was one of the comrades to urge a more militant policy. Others included a small grouping in New York City who would have some influence on the later anti-revisionist milieu.

More important for the party was the renewal of state persecution of the CPUSA and, crucially, the turning away of allies within the trades unions. Losing allies within the unions and facing McCarthyite attacks, party militants were systematically weeded out of the unions by various ruses, including loyalty pledges. The raiding of CPUSA-influenced unions by other unions reduced their support base, further isolating them. A number of unions were decimated by this offensive, as radicals and progressives unconnected to the party were sacked, including the Trotskyist arch-enemies of the party. In large parts of the country, members of the party were actually forced underground as the party moved back to functioning as a semi-legal organisation.

Government prosecutions

When the Communist Party was formed in 1919 the United States government was engaged in prosecution of Socialists who had opposed World War I and military service. This persecution was continued in 1919 and January, 1920 in the Palmer Raids or the Red Scare. Many ordinary members of the Party were arrested and deported; leaders were prosecuted and in some cases sentenced to prison terms. In the late 1930s with the authorization of President Franklin Roosevelt the FBI began investigating both domestic Nazis and Communists. The Smith Act which outlawed advocacy of violent overthrow of the government was passed in 1940.

It was during 1940 to 1949 that Herbert Philbrick acting as a citizen volunteer joined the Communist Party while meanwhile transmitting a record of his activities and contacts to the FBI. He surfaced, together with a few others, at the trial under the Smith Act of the leadership of the Communist Party in 1949, United States v. Foster, et. al..

Discoveries of instances of Soviet espionage and Communist infiltration of government and industry resulted in great apprehension during the postwar period about Communist activities [1]. Much of this was justified but particularly in the case of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his ilk there were excesses. Such excessive suspicion and persecution became known as McCarthyism and resulted in a backlash; see Reaction to McCarthyism.

In 1948, Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster and other CPUSA leaders were arrested under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government".

The case began in March, 1948. It was difficult for the prosecution to prove that the twelve men had broken the Alien Registration Act, as none of the defendants had ever openly called for violence or had been involved in accumulating weapons for a proposed revolution. The prosecution therefore relied on passages from the work of Karl Marx and other revolutionary figures from the past.

Although the CPUSA vehemently opposed prosecution of its members under the Smith Act in 1948, when Trotskyists of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) became the first to be prosecuted under the Smith Act in 1941, the CPUSA leadership supported the prosecution and convictions. This can be traced to the party's subservience to Moscow and Stalin’s hatred of Leon Trotsky and his followers. The SWP in stark contrast sought to defend the Communists.

Another strategy of the prosecution was to ask the defendants questions about other party members. Unwilling to provide information on others, they were put in prison and charged with contempt of court. The trial dragged on for eleven months and eventually, the judge, Harold Medina, who some say made no attempt to disguise his own feelings about the defendants, sent the party's lawyers to prison for contempt of court.

After a nine month trial the leaders of the Communist Party were found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. They appealed to the Supreme Court but on June 4, 1951, the judges ruled, 6-2, that the conviction was legal.

This decision was followed by the arrests of 46 more communists during the summer of 1951. This included Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, who was also convicted for contempt of court after telling the judge that she would not identify people as Communists as she was unwilling "do degrade or debase myself by becoming an informer". She was also found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to two years in prison.

The crises of 1956

The 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary and the Secret Speech of Nikita Khrushchev to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union criticising Stalin had a cataclysmic effect on the CPUSA [2]. Membership plummeted and the leadership briefly faced a challenge from a loose grouping led by Daily Worker editor John Gates, which wished to democratise the party. Perhaps the greatest single blow dealt to the party in this period was the loss of the Daily Worker, published since 1924, which was suspended in 1958 due to falling circulation. Most of the critics would depart from the party demoralised, but remained active in progressive causes often working harmoniously with party members. This diaspora rapidly came to provide the audience for publications like the National Guardian and Monthly Review, which were to be important in the development of the New Left in the 1960s.

The post-1956 upheavals in the CPUSA also saw the advent of a new leadership around former steel worker Gus Hall. Hall's views were very much those of his mentor Foster, but the younger man was to be more rigorous in ensuring the party was completely orthodox than the older man in his last years. Therefore, while remaining critics who wished to liberalise the party were expelled, so too, in 1961, were other critics who sought to return the party to an even more stringent form of Stalinism. Never a coherent or organised faction, these critics would include elements on both coasts who would come together to form the Progressive Labor Movement in the early 1960's. Through Progressive Labor, which soon adopted the title of party, former CPUSA cadre would come to play a role in many of the numerous Maoist organisations of the 1970s. Jack Shulman, Foster's secretary, who also played a role in these organization, was not expelled but resigned.

Recovery after McCarthyism

In the 1970s, the CPUSA managed to grow in membership to about 25,000 members, despite the exodus of numerous Anti-Revisionist and Maoist groups from its ranks. However, in 1984, seeing the onslaught of Ronald Reagan's anti-Communist administration and decreased CPUSA membership, Gus Hall chose to end the CPUSA's nation-wide electoral campaigns, and the CPUSA has endorsed the Democratic Party in every national election ever since. The CPUSA still runs candidates for local office.

Throughout most of its history the Communist Party has been under pressure from the United States government, especially the FBI, and was heavily infiltrated. Following the McCarthy years, membership and activities of the Communist Party were kept secret with very few visible members, although many community leaders throughout the United States were affiliated with the Party.

Soviet funding of the Party

From 1959 until 1989, when Gus Hall attacked the initiatives taken by Gorbachev in the Soviet Union, the Party received a substantial subsidy from the Soviet Union. (There is at least one receipt signed by Gus Hall in the KGB archives. [3]) Starting with $75,000 in 1959 this was increased gradually to $3 million in 1987. This substantial amount reflected the Party's subservience to the Moscow line in contrast to the French and Italian Parties whose Eurocommunism deviated from the orthodox line. The cutoff of funds in 1989 resulted in a financial crisis resulting in cutting back publication in 1990 of the Party newspaper, the People's Daily World to weekly publication, the People's Weekly World. [References for this section are provided below.]

Idealism of Party members

Communist party members consider Party membership an honor and often work very hard toward realization of the idealistic goals of communism. Generally the life of a Communist is organized around Party activities with the expectation that they will in a disciplined way advance the goals of the Party.

Organizing

Like most political parties, Communists have often participated in the organization of independent organizations (front groups) which support some aspect of their platform or serve organizing goals. In addition, Communist Party members, working together within an organization such as a labor union proceeding skillfully, were often able, together with others who supported them (or at least did not actively oppose them), to rise to leadership positions and in some cases to dominate the organization. In some cases, especially in labor organizations such as the Screen Actors Guild this practice resulted in a backlash as more conservative members such as Ronald Reagan [4] competed for control of the organization. Many conservatives opportunistically used red-baiting to attack and force the expulsion of Communists from union leadership and even their jobs.

CPUSA funding and espionage

With the declassification of the FBI's files on the CPUSA, Russian archives holding the records of the Communist International and the CPUSA, and decrypted World War II Soviet messages between KGB offices in the United States and Moscow, also known as the Venona Cables, the extent of the CPUSA's involvement of espionage is now becoming public knowledge. The USSR covertly subsidized the CPUSA from its foundation in 1919 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Releases from the Comintern archives show that all national Communist parties which conformed to the Soviet line were funded in the same fashion. From the Communist point of view this international funding arose from the internationalist nature of communism itself; fraternal assistance was considered the duty of Communists in any one country to give aid to their comrades in other countries.

Documentation released since 1991 from former Soviet states confirms suspicions that Soviet money continued to flow into the United States and buy influence within the CPUSA. Funding paid organizers, published newspapers and other Communist materials, and supported a variety of fraternal, educational and Union activities influenced by the CPUSA. Sometimes these funds were transferred as unspecified subsidies, but often they were earmarked by the Comintern for various uses. While the prominence and activity of the CPUSA was greatly reduced after the 1950s, the recently released documents show some transfers of Soviet money occurring as late as 1987. Gus Hall requested two million dollars for the publication of the Daily Worker and the rental fees for the CPUSA headquarters.

Also, it is now known that on April 10, 1943 KGB agent and New York resident Vassili M. Zarubin met CPUSA official Steve Nelson in Oakland and discussed espionage. Even Robert Meeropol, son of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, when pressed on PBS’s Frontline, admitted the possibility that his father may have participated in espionage after reading Venona transcripts which spoke of Julius Rosenberg's meeting with KGB and NKVD agents. However, Meeropol argues in his book, An Execution in the Family (St. Martin's Press, 2003, ISBN 0312306369), that Venona completely exonerated his mother, and that in any event both of his parents were killed for crimes they did not commit. David Greenglass, who is indicated in the Venona transcripts as a greater espionage figure than Julius Rosenberg, was not tried or convicted after he named his sister Ethel and Julius as spies.

Theodore Alvin Hall, a Harvard trained physicist and CPUSA member began passing information on the atomic bomb to the Soviets soon after he was hired at Los Alamos at age 19. Hall, who was known as Mlad by his KGB handlers, escaped prosecution. Hall's wife, aware of his espionage, claims that their KGB handler had advised them to plead innocence, like the Rosenberg’s did, if formally charged. Historian Ronald Radosh questions whether Joseph Stalin would have given Kim Il Sung the green light to start the Korean War had the Soviet Union not possessed atomic weapons thus sparing the millions of lives lost in the conflict. Conversely, historians of the Koren conflict wonder if the US would have backed Douglas MacArthur's plans to drop an atomic bomb on China (thus possibly causing millions of deaths) had the USSR not had nuclear weapons of its own.

Current activities

The current National Chair is Sam Webb. The newspaper is the People's Weekly World. The monthly journal is Political Affairs.

Leaders of the Communist Party USA

- Charles Ruthenberg, General Secretary (1919-1927), James P. Cannon, Party Chairman, (1919-1928)

- Jay Lovestone (1927-1929)

- William Z. Foster (1929-1932)

- Earl Browder (1932-1945)

- Eugene Dennis, General Secretary (1945-1959) and William Z. Foster, Party Chairman (1945-1957)

- Gus Hall (1959-2000)

- Sam Webb (since 2000)

See also

External links

- Official website, including FAQ's

- Official newspaper

- Party's Monthly publication

- Article: Communists Should Not Teach In American Colleges, 1949, by Raymond B. Allen, President of the University of Washington, Seattle.

- Article: Guilty as charged by Arnold Beichman, survey of Soviet documents on Communists in America Hoover Institute - Hoover Digest 1999.

References

References for: Soviet funding of the Party

- The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, Basic Books, 1999, hardcover edition, p. 287-293, p. 306, ISBN 0465003109. Vasili Mitrokhin was an archivist who worked for the KGB. After 1972, when the KGB established its new modern offices at Yasenovo, Mitrokhin was entrusted with transferring the corpus of KGB files from its old office at the Lubyanka in Moscow to the new offices. During the next ten years while performing these duties he copied many files which he turned over to British intelligence when he defected in March, 1992.

- Operation Solo: The FBI's Man in the Kremlin, John Barron, Regnery Publishing, 1996, ISBN 0895264862; 2001 edition, ISBN 0709160615. This biography of Morris Childs, who together with his brother Jack arranged for and handled the money transfers during the 1960s and 70s, contains much of the same material.

Further reading

- American Communist History a peer-reviewed journal published by the Historians of American Communism. [5]

- Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes, "The American Communist Movement: Storming Heaven Itself, Twayne Publishers (Macmillan), 1992, hardcover, 210 pages, ISBN 080573855X, trade paperback ISBN 0805738568

- Theodor Draper, The Roots of American Communism, Viking, 1957

- Theodor Draper, American Communism and Soviet Russia: The Formative Period, Viking, 1960

- Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism:The Depression Decade, Basic Books, 1984, hardcover, ISBN 0465029450, trade paperback, 1985, ISBN 0465029469

- Maurice Isserman, Which Side Were You On?: The American Communist Party During the Second World War, Wesleyan University Press, 1982 and 1987, University of Illinois Press, 1993, trade paperback, ISBN 0252063368, reprint edition ISBN 0819561118

- Philip J. Jaffe, Rise and Fall of American Communism, Horizon Press, 1975, hardcover, ISBN 0818008172

- Joseph R. Starobin, American Communism in Crisis, 1943-1957, Harvard University Press, 1972, hardcover, ISBN 0674022750

- Irving Howe and Lewis Coser, The American Communist Party: A Critical History, Beacon Press, 1957

- Guenter Lewy, The Cause That Failed: Communism in American Political Life, Oxford University Press, 1997, hardcover, ISBN 0195057481

- Aileen S. Kraditor, Jimmy Higgins: The Mental World of the American Rank-And-File Communist, 1930-1958 Greenwood Publishing Company, 1988, hardcover, ISBN 0313262462

Union history

- Bert Cochran, Labor and Communism: The Conflict That Shaped American Unions, Princeton University Press, 1977, ISBN 0691046441

- Harvey Levenstein, Communism, Anticommunism, and the CIO, Greenwood, 1981, hardcover, ISBN 0313220727

- Max M. Kampelman, Communist Party Vs the Cio: A Study in Power Politics (American Labor Series No. 2), Ayer Company Publishing, 1971, hardcover, ISBN 0405029292

- Ronald W. Schatz, Electrical Workers: A History of Labor at General Electric and Westinghouse, 1923-60, University of Illinois Press, 1983, hardcover, ISBN 0252010310; paperback reprint ISBN 0252014383

- Joshua B. Freeman, In Transit: The Transport Workers Union in New York City, 1933-1966 With a New Epilogue, Temple University Press, 2001, trade paperback 446 pages, ISBN 156639922X

- Roger Keeran, Communist Party and the Auto Workers Unions, Indiana University Press, 1980, hardcover, ISBN 0253157544

- Cletus E. Daniel, Bitter Harvest: A History of California Farmworkers, 1870-1941, University of California Press, 1982, trade paperback, ISBN 0520047222; textbook binding, Cornell University Press, 1981, ISBN 0801412846

Agricultural issues

- Robin D.G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, University of North Carolina Press, 1990, trade paperback, ISBN 0807842885

- Lowell K., Dyson, Red Harvest: The Communist Party and American Farmers, University of Nebraska Press, 1982, hardcover, ISBN 0803216599

Social and ethnic issues

- Nathan Glazer, The Social Basis of American Communism, Greenwood, 1974, ISBN 0837174767

- Harvey E. Klehr, Communist Cadre: The Social Background of the American Communist Party, Hoover Institution Press, 1960, ISBN 0685672794

- Auvo Kostiainen, The Forging of Finnish-American Communism, 1917-1924: A Study in Ethnic Radicalism, Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, Series B, No. 147, University of Turku, Turku, Finland, 1978

- Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression, University of Illinois Press, 1983, hardcover, ISBN 0252006445; Grove Press reprint, 1985, ISBN 0802151833

- Charles H., Martin, The Angelo Herndon Case and Southern Justice Louisiana State University Press, 1976, ISBN 0807101745

- Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro a Tragedy of the American South, Oxford University Press, 1972, trade paperback, ISBN 0195014855; Louisiana State University Press; 1979, trade paperback, ISBN 0807104981

Related issues

- Daniel Aaron, Writers on the Left: Episodes in American Literary Communism, Harcourt Brace & World, 1959

- Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960, Doubleday, 1980, hardcover, ISBN 0385129009; University of Illinois Press, 2003, trade paperback, 576 pages, ISBN 0252071417

- Robert Rosenstone, Crusade on the Left: The Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War, Pegasus, 1969.

- Constance Ashton Myers, The Prophet's Army : Trotskyists in America, 1928-1941, Greenwood, 1977, hardcover, 281 pages, ISBN 0837190304

- Robert Jackson Alexander and Robert S. Alley, Right Opposition: The Lovestoneites and the International Communist Opposition of the 1930's, Greenwood, 1981, hardcover, 342 pages, ISBN 0313220700

New Left

- Peter Collier and David Horowitz, Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts about the '60s, Summit Books, 1989, hardcover, ISBN 0671667521; Summit Books, trade paperback, ISBN 0671701282; Simon and Schuster, 1996, trade paperback, 398 pages, ISBN 0684826410

- Todd Gitlin, Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, Bantam, 1987, hardcover, ISBN 0553052330; Bantam Dell, 1993, trade paperback, ISBN 0553372122

- James E. Miller also known as Jim or James Miller, Democracy Is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago, Touchstone Books, 1988, hardcover, ISBN 0671530569; Harvard University Press, 1994, trade paperback, ISBN 0674197259; Touchstone Books, 1988, trade paperback, ISBN 067166235X

Espionage and infiltration

- Allen, Weinstein, Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case, Knopf, 1978, hardcover, ISBN 0394495462

- Ronald Radosh and Joyce Milton, The Rosenberg File: A Search for the Truth, Henry Holt, 1983, hardcover, ISBN 0030490367; Yale University Press, 2nd edition, 1997, trade paperback, 616 pages, ISBN 0300072058

- Earl Latham, Communist Controversy in Washington: From the New Deal to McCarthy, Holiday House, 1972, ISBN 0689701217; hardcover, ISBN 1125650796

- Richard M. Fried, Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective, Oxford University Press, 1991, trade paperback, ISBN 019504360X; ISBN 0195043618

Joe McCarthy

- David M. Oshinsky, Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy, Simon and Schuster, 1985, trade paperback, ISBN 0029237602; Free Press, ISBN 0029234905

- Thomas C. Reeves, Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, Stein & Day, 1983, hardcover, ISBN 0812823370

Bibliography

- John Earl Haynes, Communism and Anti-Communism in the United States: An Annotated Guide to Historical Writings (Garland Reference Library of Social Science, Vol 379), Garland Science, 1987, hardcover ISBN 0824085205

- Newsletter of the Historians of American Communism