Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Maximilian I (also known as Maximilian Joseph) (27 May 1756 – 13 October 1825) was Duke of Zweibrücken from 1795 to 1799, Prince-Elector of Bavaria (as Maximilian IV Joseph) from 1799 to 1805, King of Bavaria (as Maximilian I) from 1806 to 1825. He was a member of the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld, a branch of the House of Wittelsbach.

Biography

Early life

Maximilian, the son of the count palatine Frederick Michael of Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld and Maria Francisca of Sulzbach, was born on the 27 May 1756 at Schwetzingen – between Heidelberg and Mannheim.[citation needed]

After his father's death and with a mother having been repudiated "for her immoral lifestyle", he was carefully educated under the supervision of his uncle, Duke Christian IV of Zweibrücken[1] who settled him in the Hôtel des Deux-Ponts, became Count of Rappoltstein in 1776,[citation needed] and took service in 1777 as a colonel in the French army and rose rapidly to the rank of major-general.[1] From 1782 to 1789 he was stationed at Strasbourg.[1] During his time at the University Klemens von Metternich, the future Austrian chancellor was for some time accommodated by Prince Maximilian.[2] By the outbreak of the French Revolution Maximilian exchanged the French for the Austrian service, taking part in the opening campaigns of the revolutionary wars.[1]

Duke of Zweibrücken and Elector of Bavaria and the Palatinate

On 1 April 1795 he succeeded his brother, Charles II, as duke of Zweibrücken, however, his duchy was entirely occupied by the French.[1] On 16 February 1799 Maximilian Joseph became Elector of Bavaria[1] and Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Arch-Steward of the Empire, and Duke of Berg on the extinction of the Palatinate-Sulzbach line with the death of the elector Charles Theodore.[1]

The sympathy with France and with French ideas of enlightenment which characterized his reign was at once manifested. In the newly organized ministry Count Max Josef von Montgelas, who, after falling into disfavour with Charles Theodore, had acted for a time as Maximilian Joseph's private secretary, was the most potent influence, an influence wholly "enlightened" and French.[1] Agriculture and commerce were fostered, the laws were ameliorated, a new criminal code drawn up, taxes and imposts equalized without regard to traditional privileges, while a number of religious houses were suppressed and their revenues used for educational and other useful purposes.[1] He closed the University of Ingolstadt in May 1800 and moved it to Landshut.[citation needed]

In foreign politics Maximilian Joseph's attitude was from the German point of view less commendable. With the growing sentiment of German nationality he had from first to last no sympathy, and his attitude throughout was dictated by wholly dynastic, or at least Bavarian, considerations. Until 1813 he was the most faithful of Napoleon's German allies, the relation being cemented by the marriage of his eldest daughter to Eugène de Beauharnais. His reward came with the Treaty of Pressburg (26 December 1805), by the terms of which he was to receive the royal title and important territorial acquisitions in Swabia and Franconia to round off his kingdom. He assumed the title of king on 1 January 1806.[1] On 15 March he ceded the Duchy of Berg to Napoleon's brother-in-law Joachim Murat.[citation needed]

King of Bavaria

The new King of Bavaria was the most important of the princes belonging to the Confederation of the Rhine, and remained Napoleon's ally until the eve of the Battle of Leipzig, when by the Treaty of Ried (8 October 1813) he made the guarantee of the integrity of his kingdom the price of his joining the Allies.[1] On 14 October, Bavaria made a formal declaration of war against Napoleonic France. The treaty was passionately backed by Crown Prince Ludwig and by Marshal von Wrede.[citation needed]

By the first Treaty of Paris (3 June 1814), however, he ceded Tyrol to Austria in exchange for the former Grand Duchy of Würzburg. At the Congress of Vienna, which he attended in person, Maximilian had to make further concessions to Austria, ceding Salzburg and the regions of Innviertel and Hausruckviertel[citation needed] in return for the western part of the old Palatinate. The king fought hard to maintain the contiguity of the Bavarian territories as guaranteed at Ried but the most he could obtain was an assurance from Metternich in the matter of the Baden succession, in which he was also doomed to be disappointed.[3]

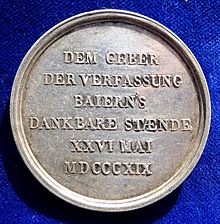

At Vienna and afterwards Maximilian sturdily opposed any reconstitution of Germany which should endanger the independence of Bavaria, and it was his insistence on the principle of full sovereignty being left to the German reigning princes that largely contributed to the loose and weak organization of the new German Confederation. The Federative Constitution of Germany (8 June 1815) of the Congress of Vienna was proclaimed in Bavaria, not as a law but as an international treaty. It was partly to secure popular support in his resistance to any interference of the federal diet in the internal affairs of Bavaria, partly to give unity to his somewhat heterogeneous territories, that Maximilian on 26 May 1818 granted a liberal constitution to his people. Montgelas, who had opposed this concession, had fallen in the previous year, and Maximilian had also reversed his ecclesiastical policy, signing on 24 October 1817 a concordat with Rome by which the powers of the clergy, largely curtailed under Montgelas's administration, were restored.[1]

The new parliament proved to be more independent than he had anticipated and in 1819 Maximilian resorted to appealing to the powers against his own creation; but his Bavarian "particularism" and his genuine popular sympathies prevented him from allowing the Carlsbad Decrees to be strictly enforced within his dominions. The suspects arrested by order of the Mainz Commission he was accustomed to examine himself, with the result that in many cases the whole proceedings were quashed, and in not a few the accused dismissed with a present of money.[1]

Maximilian died at Nymphenburg Palace, near Munich,[citation needed] on 13 October 1825 and was succeeded by his son Ludwig I.[1] Maximilian is buried in the crypt of the Theatinerkirche in Munich.[citation needed]

Cultural legacy

Under the reign of Maximilian Joseph the Bavarian Secularization (1802–1803) led to the nationalisation of cultural assets of the Church. The Protestants were emancipated. In 1808 he founded the Academy of Fine Arts Munich.[citation needed]

The city of Munich was extended by the first systematic expansion with the new Brienner Strasse as core. In 1810 Max Joseph ordered construction of the National Theatre Munich in French neo-classic style. The monument Max-Joseph Denkmal before the National Theatre was created in the middle of the square Max-Joseph-Platz as a memorial for King Maximilian Joseph by Christian Daniel Rauch and carried out by Johann Baptist Stiglmaier. It was only revealed in 1835 since the king had rejected to be eternalized in sitting position.[citation needed]

In 1801 he led the rescue operation when a glassmaker's workshop collapsed, saving the life of Joseph von Fraunhofer, a 14-year-old orphan apprentice. Max Joseph donated books and directed the glassmaker to give Fraunhofer time to study. Fraunhofer went on to become one of the most famous optical scientists and artisans in history, inventing the spectroscope and spectroscopy, making Bavaria noted for fine optics, and joining the nobility before his death at age 39.[citation needed]

He was elected a Royal Fellow of the Royal Society in 1802.[4]

Private life and family

Maximilian married twice[1] and had children by both marriages:[citation needed]

His first wife was Auguste of Hesse-Darmstadt,[1] daughter of Prince Georg Wilhelm of Hesse-Darmstadt (14 April 1765 – 30 March 1796). They were married on 30 September 1785 in Darmstadt.[citation needed] They had five children:[citation needed]

- Crown Prince Ludwig (1786–1868), married Therese of Saxe-Hildburghausen.

- Princess Augusta Amalia Ludovika, (21 June 1788 – 13 May 1851), married Eugène de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg.

- Princess Amalie Marie Auguste (9 October 1790 – 24 January 1794), died in infancy.

- Princess Caroline Augusta (8 February 1792 – 9 February 1873), married William I of Württemberg, and then Francis II of Austria.

- Prince Karl Theodor Maximilian (7 July 1795 – 16 August 1875).

Maximilian's second wife was Karoline of Baden,[1] daughter of Margrave Karl Ludwig of Baden (13 July 1776 – 13 November 1841). They were married on 9 March 1797 in Karlsruhe.[citation needed] They had eight children:[citation needed]

- Stillborn son (5 September 1799)

- Prince Maximilian Joseph Karl Friedrich (28 October 1800 – 12 February 1803), died in infancy.

- Princess Elisabeth Ludovika ("Elise") (13 November 1801 – 14 December 1873), married Frederick William IV of Prussia.

- Princess Amalie Auguste (13 November 1801 – 8 November 1877), married John I of Saxony.

- Princess Sophie Friederike Dorothee (27 January 1805 – 1872), married Archduke Franz Karl of Austria, mother of Franz Joseph I of Austria and Maximilian I of Mexico.

- Princess Marie Anne Leopoldine (27 January 1805 – 13 September 1877), married Frederick Augustus II of Saxony.

- Princess Ludovika Wilhelmine (1808–1892), married Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria.

- Princess Maximiliana (21 July 1810 - 4 February 1821), died in childhood.

Styles

- 27 May 1756 - 1 April 1795: His Serene Highness Prince Maximillian Joseph of Bavaria

- 1 April 1795 - 16 February 1799: His Highness The Duke of Zweibrücken

- 16 February 1799 - 1 January 1806: His Highness The Duke of Zweibrücken, Elector of Bavaria, Duke of Berg, Elector Palatine

- 1 January 1806 - 13 October 1825: His Majesty The King of Bavaria

Ancestry

| King Maximilian I Joseph's relation to Elector Maximilian I of Bavaria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

References

- Palmer, Alan (1972). Metternich: Councillor of Europe (1997 reprint ed.). London: Orion. ISBN 978-1-85799-868-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Libray Catalog". Royal Society. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Maximilian I, King of Bavaria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 921.

- People from Schwetzingen

- House of Wittelsbach

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Kings of Bavaria

- Princes of Bavaria

- Roman Catholic monarchs

- Counts Palatine of Neuburg

- Counts Palatine of Sulzbach

- Counts Palatine of Zweibrücken

- 19th-century monarchs in Europe

- Dukes of Jülich

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Joseph

- Academy of Fine Arts, Munich

- 1756 births

- 1825 deaths

- Burials at the Theatine Church, Munich