Muzo

Muzo

Villa de la Santísima Trinidad de los Muzos | |

|---|---|

Municipality and town | |

View of Muzo | |

| Etymology: Muzo | |

| Nickname: Emerald capital of the world | |

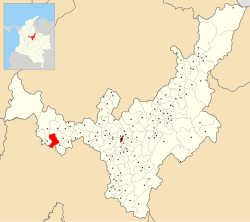

Location of the municipality and town of Muzo in the Boyacá Department of Colombia | |

| Coordinates: 5°31′52.8″N 74°06′26.2″W / 5.531333°N 74.107278°W | |

| Country | |

| Department | Boyacá Department |

| Province | Western Boyacá Province |

| Founded | 20 February 1559 |

| Founded by | Luis Lanchero |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Neicer Albeiro Susa Sotelo (2020–2023) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality and town | 147 km2 (57 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 815 m (2,674 ft) |

| Population (2015) | |

| • Municipality and town | 9,040 |

| • Density | 61/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 5,350 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Colombia Standard Time) |

| Website | Official website |

Muzo (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈmuso]) is a town and municipality in the Western Boyacá Province, part of the department of Boyacá, Colombia. It is widely known as the world capital of emeralds for the mines containing the world's highest quality gems of this type. Muzo is situated at a distance of 178 kilometres (111 mi) from the departmental capital Tunja and 118 kilometres (73 mi) from the capital of the Western Boyacá Province, Chiquinquirá. The urban centre is at an altitude of 815 metres (2,674 ft) above sea level. Muzo borders Otanche and San Pablo de Borbur in the north, Maripí and Coper in the east, Quípama in the west and the department of Cundinamarca in the south.[1]

Etymology[edit]

The town of Muzo was called Villa de la Santísima Trinidad de los Muzos, or simply Trinidad, when the Spanish conquistadors first founded the settlement in western Boyacá. Muzo is the autonym of the Muzo, the indigenous people who inhabited the region before the Spanish conquest.[1]

Climate[edit]

The median temperature of Muzo is 26 °C (79 °F) and the annual precipitation 3,152 millimetres (124.1 in).[1]

History[edit]

Before the Spanish conquest of the Eastern Colombian Andes, the region of Muzo was inhabited by the people with the same name. They extracted emeralds in pre-Columbian times, giving them the name "The Emerald People". Using poles of hard tropical wood and water, the people peeled the emeralds from the formations, in particular the Muzo Formation, named after the municipality. Historians have estimated the Muzo settled in the area of Muzo around 1000 AD.[2]

The Cariban-speaking Muzo, like their Chibcha neighbours, adored the Sun and Moon as deities. Unlike their eastern neighbours, they did not construct temples.[3]

Spanish conquest[edit]

After the successful conquest by the Spanish of the eastern neighbours, the Muisca, and partial submittal of the Panche, the southern neighbours of the Muzo, the Spanish, in search of valuable resources, sent various conquistadors into the territories inhabited by the Muzo. The first to arrive in Muzo territory was Luis Lanchero, soldier of the conquest expedition led by Nikolaus Federmann, in 1539.[4] He encountered fierce resistance by the indigenous Muzo and had to return to the newly founded capital Santafe de Bogotá of the New Kingdom of Granada in 1541. The Muzo used the rugged terrain to their advantage and attacked the forty conquistadors, whose horses had problems crossing the hills of Muzo, using poisoned arrows.[5] During a second invasion by the Spanish into the Muzo lands, in 1544, conquistador Diego Martínez discovered the rich emerald deposits of Muzo.[6]

A third campaign to submit the Muzo was executed by conquistador Pedro de Ursúa in 1552. Also he failed to conquer the Muzo. A fourth time the Spanish attempted to subdue the Muzo to the Spanish Crown was successful; Luis Lanchero returned to the area where he was driven out almost two decades earlier, defeated the Muzo and founded the town of Villa de la Santísima Trinidad de los Muzos on February 20, 1559.[1]

Colonial period[edit]

The first evangelisation was performed by Juan de los Barrios in 1566. The Spanish were highly interested in the emeralds of Muzo, proving to be the highest quality emeralds worldwide.[1] They set up encomiendas to guard the valuable gemstones and used the indigenous people to perform slave labour for the extraction of the minerals.

Economy[edit]

The main economical activity with approximately 75% of the municipal income is emerald mining. Agriculture and livestock farming comprise the remaining quarter of the economy of Muzo. Agricultural products cultivated are sugarcane, cacao, yuca, avocadoes and citrus fruits.[1]

Emerald mining[edit]

The Muzo mines are situated in the western flank of the Eastern ranges of the Colombian Andes. The Devonshire, one of the world's most famous uncut emeralds, is from the Muzo mines. It is a 1,383.95 carats (276.790 g) emerald and was a gift to the 6th Duke of Devonshire by Emperor Dom Pedro I of Brazil in 1831.

The US National Museum Division of Mineralogy and Petrology carried out a study of the mines in 1916.

Gallery[edit]

-

Emerald from Muzo

-

Muzo emeralds

-

Emerald

-

Individual emerald

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Branquet, Yannick; Laumonier, Bernard; Cheilletz, Alain; Giuliani, Gaston (1999). "Emeralds in the Eastern Cordillera of Colombia: Two tectonic settings for one mineralization" (PDF). Geology. 27: 597–600. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Giuliani, Gaston; Cheilletz, Alain; Arboleda, Carlos; Carrillo, Victor; Rueda, Félix; Baker, James H. (1995). "An evaporitic origin of the parent brines of Colombian emeralds: fluid inclusion and sulphur isotope evidence" (PDF). European Journal of Mineralogy. 7: 151–165. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Henao, Jesús María; Arrubla, Gerardo (1820). Historia de Colombia para la enseñanza secundaria [History of Colombia for the secondary education] (in Spanish). Indiana University. pp. 1–592. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Ortega Medina, Laura Milena (2007). Tipología y condiciones de formación de las manifestaciones del sector esmeraldífero "Peña Coscuez" (municipio San Pablo de Borbur, Boyacá) (PDF) (MSc. thesis). Universidad Industrial de Santander. pp. 1–121. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- Ocampo López, Javier (2013). Mitos y leyendas indígenas de Colombia [Indigenous myths and legends of Colombia] (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A. ISBN 978-958-14-1416-1.

- Pignatelli, Isabella; Giuliani, Gaston; Ohnenstetter, Daniel; Agrosì, Giovanna; Mathieu, Sandrine; Morlot, Christophe; Branquet, Yannick (2015). "Colombian Trapiche Emeralds: Recent Advances in Understanding Their Formation". Gems & Gemology. LI: 222–259.

- Puche Riart, Octavio (1996). La explotación de las esmeraldas de Muzo (Nueva Granada), en sus primeros tiempos [The exploitation of the emeralds of Muzo (New Kingdom of Granada), the first period] (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. 3. pp. 99–104. ISBN 0902806-38-6. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Tequia Porras, Humberto (2008). Asentamiento español y conflictos encomenderos en Muzo desde 1560 a 1617 - Spanish settlement and encomienda conflicts in Muzo from 1560 to 1617 (M.A.) (PDF) (M.A. thesis) (in Spanish). Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. pp. 1–91. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Uribe, Sylvano E. (1960). "Las esmeraldas de Colombia" [The emeralds from Colombia] (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia. 65 (in Spanish). XVIII: 1–8. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

External links[edit]

- MUZO Emerald Colombia official site of Muzo Emeralds, with details on the emerald mine

- The Emerald Deposits of Muzo, Colombia Online copy of the 1916 U.S. National Museum study