Myeloperoxidase

| Myeloperoxidase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.11.2.2 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Template:PBB Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a peroxidase enzyme that in humans is encoded by the MPO gene.[1] Myeloperoxidase is most abundantly expressed in neutrophil granulocytes (a subtype of white blood cells).[2] It is a lysosomal protein stored in azurophilic granules of the neutrophil and released into the extracellular space during degranulation. MPO has a heme pigment, which causes its green color in secretions rich in neutrophils, such as pus and some forms of mucus.

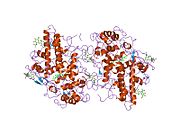

Structure

The 150-kDa MPO protein is a dimer consisting of two 15-kDa light chains and two variable-weight glycosylated heavy chains bound to a prosthetic heme group. Three isoforms have been identified, differing only in the size of the heavy chains.[3] It contains a calcium binding site with seven ligands, forming a pentagonal pyramid conformation. One of the ligands is the carbonyl group of Asp 96. Calcium-binding is important for structure of the active site because of Asp 96's close proximity to the catalytic His95 side chain.

Function

MPO produces hypochlorous acid (HOCl) from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and chloride anion (Cl−) (or the equivalent from a non-chlorine halide) during the neutrophil's respiratory burst. It requires heme as a cofactor. Furthermore, it oxidizes tyrosine to tyrosyl radical using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidizing agent.[4]

Hypochlorous acid and tyrosyl radical are cytotoxic, so they are used by the neutrophil to kill bacteria and other pathogens.

Inhibitors of MPO

Azide has been used traditionally as an MPO inhibitor, but 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (4-ABH) is a more specific inhibitor of MPO.[5]

Genetics

The human gene is located on chromosome 17 (17q23.1).[1]

Role in disease

Myeloperoxidase deficiency is a hereditary deficiency of the enzyme, which predisposes to immune deficiency.[6]

Antibodies against MPO have been implicated in various types of vasculitis, most prominently crescentic glomerulonephritis and Churg-Strauss syndrome. They are detected as perinuclear ANCAs (p-ANCAs), as opposed to the cytoplasmic ANCAs (c-ANCAs) against proteinase-3 (PR3), which are strongly associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Recent studies have reported an association between elevated myeloperoxidase levels and the severity of coronary artery disease.[7] And Heslop et al. reported that elevated MPO levels more than doubled the risk for cardiovascular mortality over a 13-year period.[8] It has also been suggested that myeloperoxidase plays a significant role in the development of the atherosclerotic lesion and rendering plaques unstable.[9][10]

Medical uses

An initial 2003 study suggested that MPO could serve as a sensitive predictor for myocardial infarction in patients presenting with chest pain.[11] Since then, there have been over 100 published studies documenting the utility of MPO testing. The 2010 Heslop et al. study reported that measuring both MPO and CRP (C-reactive protein; a general and cardiac-related marker of inflammation) provided added benefit for risk prediction than just measuring CRP alone.[8]

Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase used to be administered in the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia to demonstrate that the leukemic cells were derived from the myeloid lineage. However, the use of myeloperoxidase staining in this setting has been supplanted by the widespread use of flow cytometry.[citation needed] Myeloperoxidase staining is still important in the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma, contrasting with the negative staining of lymphomas, which can otherwise have a similar appearance.[12]

Myeloperoxidase is the first and so far only human enzyme known to break down carbon nanotubes, allaying a concern among clinicians that using nanotubes for targeted delivery of medicines would lead to an unhealthy buildup of nanotubes in tissues.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: Myeloperoxidase".

- ^ Klebanoff SJ (May 2005). "Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe". J. Leukoc. Biol. 77 (5): 598–625. doi:10.1189/jlb.1204697. PMID 15689384.

- ^ Mathy-Hartert M, Bourgeois E, Grülke S, Deby-Dupont G, Caudron I, Deby C, Lamy M, Serteyn D (April 1998). "Purification of myeloperoxidase from equine polymorphonuclear leucocytes". Can. J. Vet. Res. 62 (2): 127–32. PMC 1189459. PMID 9553712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heinecke JW, Li W, Francis GA, Goldstein JA (June 1993). "Tyrosyl radical generated by myeloperoxidase catalyzes the oxidative cross-linking of proteins". J. Clin. Invest. 91 (6): 2866–72. doi:10.1172/JCI116531. PMC 443356. PMID 8390491.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kettle AJ, Gedye CA, Winterbourn CC (January 1997). "Mechanism of inactivation of myeloperoxidase by 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide". Biochem. J. 321. ( Pt 2): 503–8. PMC 1218097. PMID 9020887.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kutter D, Devaquet P, Vanderstocken G, Paulus JM, Marchal V, Gothot A (2000). "Consequences of total and subtotal myeloperoxidase deficiency: risk or benefit ?". Acta Haematol. 104 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1159/000041062. PMID 11111115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, Aviles RJ, Pearce GL, Penn MS, Topol EJ, Sprecher DL, Hazen SL (November 2001). "Association between myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease". JAMA. 286 (17): 2136–42. doi:10.1001/jama.286.17.2136. PMID 11694155.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Heslop CL, Frohlich JJ, Hill JS (March 2010). "Myeloperoxidase and C-reactive protein have combined utility for long-term prediction of cardiovascular mortality after coronary angiography". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55 (11): 1102–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.050. PMID 20223364.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nicholls SJ, Hazen SL (June 2005). "Myeloperoxidase and cardiovascular disease". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 (6): 1102–11. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000163262.83456.6d. PMID 15790935.

- ^ Lau D, Baldus S (July 2006). "Myeloperoxidase and its contributory role in inflammatory vascular disease". Pharmacol. Ther. 111 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.023. PMID 16476484.

- ^ Brennan ML, Penn MS, Van Lente F, Nambi V, Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Goormastic M, Pepoy ML, McErlean ES, Topol EJ, Nissen SE, Hazen SL (October 2003). "Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain". N. Engl. J. Med. 349 (17): 1595–604. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035003. PMID 14573731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leong A S-Y, Cooper K, Leong, FJ W-M (2003). Manual of Diagnostic Antibodies for Immunohistology. London: Greenwich Medical Media. pp. 325–326. ISBN 1-84110-100-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kagan VE, Konduru NV, Feng W, Allen BL, Conroy J, Volkov Y, Vlasova II, Belikova NA, Yanamala N, Kapralov A, Tyurina YY, Shi J, Kisin ER, Murray AR, Franks J, Stolz D, Gou P, Klein-Seetharaman J, Fadeel B, Star A, Shvedova AA (April 2010). "Carbon nanotubes degraded by neutrophil myeloperoxidase induce less pulmonary inflammation". Nat Nanotechnol. 5 (5): 354–9. doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.44. PMID 20364135.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)