Net neutrality in the United States

| Part of a series about |

| Net neutrality |

|---|

| Topics and issues |

| By country or region |

In the United States, net neutrality has been an issue of contention among network users and access providers since the 1990s.[1] Until 2015, there were no clear legal restrictions against practices impeding net neutrality.[2][3][4][5] In 2005 and 2006, corporations supporting both sides of the issue spent large amounts of money lobbying Congress.[6] Between 2005 and 2012, five attempts to pass bills in Congress containing net neutrality provisions failed. Each sought to prohibit Internet service providers from using various variable pricing models based upon the user's Quality of Service level, described as tiered service in the industry and as price discrimination by some economists.[7][8]

In April 2014, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reported a new draft rule that would have permitted ISPs to offer content providers a faster track to send content, thus reversing its earlier net neutrality position.[9] In May 2014, the FCC decided to consider two options: permitting fast and slow broadband lanes, thereby compromising net neutrality; and second, reclassifying broadband as a telecommunication service, thereby preserving net neutrality.[10] In November 2014, President Barack Obama recommended that the FCC reclassify broadband Internet service as a telecommunications service.[11] In January 2015, Republicans presented an HR discussion draft bill that made concessions to net neutrality but prohibited the FCC from enacting any further regulation affecting ISPs.[12] On February 26, 2015, the FCC ruled in favor of net neutrality by reclassifying broadband as a common carrier under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934 and Section 706 of the Telecommunications act of 1996.[2][13][14] On April 13, 2015, the FCC published the final rule on its new "Net Neutrality" regulations.[15][16] These rules went into effect on June 12, 2015.[17]

Regulatory history

Early history 1980–early 2000s

While the term is new, the ideas underlying net neutrality have a long pedigree in telecommunications practice and regulation. The concept of network neutrality originated in the age of the telegram in 1860 or even earlier, where standard (pre-overnight telegram) telegrams were routed 'equally' without discerning their contents and adjusting for one application or another. Such networks are "end-to-end neutral".

Services such as telegrams and the phone network (officially, the public switched telephone network or PSTN) have been considered common carriers under U.S. law, which means that they have been akin to public utilities and expressly forbidden to give preferential treatment. They have been regulated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in order to ensure fair pricing and access.

In the late 1980s the Internet became legally available for commercial use, and in the early years of public use of the Internet, this was its main use - public access was limited and largely reached through dial-up modems (as was the Bulletin board system dial-up culture that preceded it). The Internet was viewed more as a commercial service than a domestic and societal system. Being business services, cable modem Internet access and high-speed data links, which make up the Internet's core, had always since their creation been categorized under U.S. law as an information service, unlike telephone services (including services by dial-up modem), and not as a telecommunications service, and thus had not been subject to common carrier regulations, as upheld in National Cable & Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Services.

However, by the late 1990s and early 2000s the Internet started to become common in households and wider society. Also in the 1980s, arguments about the public interest requirements of the telecommunications industry in the U.S. arose; whether companies involved in broadcasting were best viewed as community trustees, with obligations to society and consumers, or mere market participants with obligations only to their shareholders.[18] The legal debate about net neutrality regulations of the 2000s echoes this debate.

By the 1990s, some U.S. politicians began to express concern over protecting the Internet:

How can government ensure that the nascent Internet will permit everyone to be able to compete with everyone else for the opportunity to provide any service to all willing customers? Next, how can we ensure that this new marketplace reaches the entire nation? And then how can we ensure that it fulfills the enormous promise of education, economic growth and job creation?

In the early 2000s, legal scholars such as Tim Wu and Lawrence Lessig raised the issue of neutrality in a series of academic papers addressing regulatory frameworks for packet networks. Wu in particular noted that the Internet is structurally biased against voice and video applications. The debate that started in the U.S. extended internationally with distinct differences of the debate in Europe.[20]

FCC promotes freedom without regulation (2004)

In February 2004 then Federal Communications Commission Chairman Michael Powell announced a set of non-discrimination principles, which he called the principles of "Network Freedom". In a speech at the Silicon Flatirons Symposium, Powell encouraged ISPs to offer users these four freedoms:

- Freedom to access content.

- Freedom to run applications.

- Freedom to attach devices.

- Freedom to obtain service plan information.[21]

In early 2005, in the Madison River case, the FCC for the first time showed willingness to enforce its network neutrality principles by opening an investigation about Madison River Communications, a local telephone carrier that was blocking voice over IP service. Yet the FCC did not fine Madison River Communications. The investigation was closed before any formal factual or legal finding and there was a settlement in which the company agreed to stop discriminating against voice over IP traffic and to make a $15,000 payment to the US Treasury in exchange for the FCC dropping its inquiry.[22] Since the FCC did not formally establish that Madison River Communications violated laws and regulation, the Madison River settlement does not create a formal precedent. Nevertheless, the FCC's action established that it would not sit idly by if other US operators discriminated against voice over IP traffic.

CLEC, dial-up, and DSL deregulation (2004–2005)

In 2004, the court case USTA v. FCC voided the FCC's authority to enforce rules requiring telephone operators to unbundle certain parts of their networks at regulated prices. This caused the economic collapse of many competitive local exchange carriers (CLEC).[23]

In the United States, broadband services were historically regulated differently according to the technology by which they were carried. While cable Internet has always been classified by the FCC as an information service free of most regulation, DSL was regulated as a telecommunications service. In 2005, the FCC reclassified Internet access across the phone network, including DSL, as "information service" relaxing the common carrier regulations and unbundling requirement.

During the FCC's hearing, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association urged the FCC to adopt the four criteria laid out in its 2005 Internet Policy Statement as the requisite openness. This made up a voluntary set of four net neutrality principles.[24] Implementation of the principles was not mandatory; that would require an FCC rule or federal law.[25] The modified principles were as follows:[26][27]

- Consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice;

- Consumers are entitled to run applications and services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement;

- Consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network; and

- Consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

In 2006, representatives from several major U.S. corporations and the federal government publicly addressed U.S. Internet services in terms of the nature of free market forces, the public interest, the physical and software infrastructure of the Internet, and new high-bandwidth technologies.[citation needed] In December 2006, the AT&T/Bell South merger agreement defined net neutrality as an agreement on the part of the broadband provider: "not to provide or to sell to Internet content, application or service providers ... any service that privileges, degrades or prioritizes any (data) packet transmitted over AT&T/BellSouth's wireline broadband Internet access service based on its source, ownership or destination."[28]

FCC attempts at enforcing Net Neutrality, 2005 - 2010

- Attempt to prevent Comcast from throttling BitTorrent

In October 2007, Comcast, the largest cable company in the US, was found to be blocking or severely delaying BitTorrent uploads on their network using a technique which involved creating 'reset' packets (TCP RST) that appeared to come from the other party.[29][30] On March 27, 2008, Comcast and BitTorrent reached an agreement to work together on network traffic where Comcast was to adopt a protocol-neutral stance "as soon as the end of [2008]", and explore ways to "more effectively manage traffic on its network at peak times."[31] In December 2009 Comcast reached a proposed settlement of US$16 million, admitting no wrongdoing[32] and amounting to no more than US$16 per share.[33]

In August 2008, the FCC made its first Internet network management decision.[34] It voted 3-to-2 to uphold a complaint against Comcast ruling that it had illegally inhibited users of its high-speed Internet service from using file-sharing software because it throttled the bandwidth available to certain customers for video files to ensure that other customers had adequate bandwidth.[35][36] The FCC imposed no fine, but required Comcast to end such blocking in the year 2008, ordered Comcast to disclose the details of its network management practices within 30 days, submit a compliance plan for ending the offending practices by the end of the year, and disclose to the public the details of intended future practices. Then-FCC chairman Kevin J. Martin said the order was meant to set a precedent, that Internet providers and all communications companies could not prevent customers from using their networks the way they see fit, unless there is a good reason. In an interview Martin stated that "We are preserving the open character of the Internet" and "We are saying that network operators can't block people from getting access to any content and any applications." The case highlighted whether new legislation is needed to force Internet providers to maintain network neutrality, i.e., treat all uses of their networks equally. The legal complaint against Comcast was related to BitTorrent, software that is commonly used for downloading movies, television shows, music and software on the Internet.[37]

- Attempt to expand 2005 FCC rules

Towards the end of 2009, FCC Chair Julius Genachowski announced at the Brookings Institution a series of proposals that would prevent telecommunications, cable and wireless companies from blocking certain information on the Internet, for example, Skype applications.[38] In September 2009, he proposed to add two rules to its 2005 policy statement, viz., the nondiscrimination principle that ISPs must not discriminate against any content or applications, and the transparency principle, requiring that ISPs disclose all their policies to customers. He argued that wireless should be subject to the same network neutrality as wireline providers.[39] In October 2009, the FCC gave notice of proposed rule making on net neutrality.[40]

- Legal outcome : FCC case rejected

In two rulings, in April and June 2010 respectively, both of the above were rejected by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in Comcast Corp. v. FCC. On April 6, 2010, the FCC's 2008 cease-and-desist order against Comcast to slow and stop BitTorrent transfers was denied. The U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the FCC has no powers to regulate any Internet provider's network, or the management of its practices: "[the FCC] 'has failed to tie its assertion' of regulatory authority to an actual law enacted by Congress",[41][42] and in June 2010, it overturned (in the same case) the FCC's Order against Comcast, ruling similarly that the FCC lacked the authority under Title One of the Communications Act of 1934, to force ISPs to keep their networks open, while employing reasonable network management practices, to all forms of legal content.[43] In May 2010, the FCC announced it would continue its fight for net neutrality.[44]

FCC's conditions for spectrum auction (2008)

In February 2008, Kevin Martin, then Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, said that he is "ready, willing and able," to prevent broadband ISPs from irrationally interfering with their subscribers' Internet access.[45]

In 2008, when the FCC auctioned off the 700 MHz block of wireless spectrum in anticipation of the DTV transition, Google promised to enter a bid of $4.6 billion, if the FCC required the winning licensee to adhere to four conditions:[46]

- Open applications: Consumers should be able to download and use any software application, content, or services they desire;

- Open devices: Consumers should be able to use a handheld communications device with whatever wireless network they prefer;

- Open services: Third parties (resellers) should be able to acquire wireless services from a 700 MHz licensee on a wholesale basis, based on reasonably nondiscriminatory commercial terms;

- Open networks: Third parties, such as Internet service providers, should be able to interconnect at any technically feasible point in a 700 MHz licensee's wireless network.

These conditions were broadly similar to the FCC's Internet Policy Statement; FCC's applications and content were combined into a single bullet, and an extra bullet requiring wholesale access for third party providers was included. The FCC adopted only two of these four criteria for the auction, viz., open devices and open applications, and only applied these conditions to the nationwide C block portion of the band.[47]

President Barack Obama's American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 called for an investment of $7.2 billion in broadband infrastructure and included an openness stipulation.

FCC Open Internet Order (2010)

In December 2010, the FCC approved the FCC Open Internet Order banning cable television and telephone service providers from preventing access to competitors or certain web sites such as Netflix. On December 21, 2010, the FCC voted on and passed a set of 6 net "neutrality principles":

- Transparency: Consumers and innovators have a right to know the basic performance characteristics of their Internet access and how their network is being managed;

- No Blocking: This includes a right to send and receive lawful traffic, prohibits the blocking of lawful content, apps, services and the connection of non-harmful devices to the network;

- Level Playing Field: Consumers and innovators have a right to a level playing field. This means a ban on unreasonable content discrimination. There is no approval for so-called "pay for priority" arrangements involving fast lanes for some companies but not others;

- Network Management: This is an allowance for broadband providers to engage in reasonable network management. These rules don't forbid providers from offering subscribers tiers of services or charging based on bandwidth consumed;

- Mobile: The provisions adopted today do not apply as strongly to mobile devices, though some provisions do apply. Of those that do are the broadly applicable rules requiring transparency for mobile broadband providers and prohibiting them from blocking websites and certain competitive applications;

- Vigilance: The order creates an Open Internet Advisory Committee to assist the Commission in monitoring the state of Internet openness and the effects of the rules.[48]

The net neutrality rule did not keep ISPs from charging more for faster access. The measure was denounced by net neutrality advocates as a capitulation to telecommunication companies such as allowing them to discriminate on transmission speed for their profit, especially on mobile devices like the iPad, while pro-business advocates complained about any regulation of the Internet at all. Republicans in Congress announced to reverse the rule through legislation.[49][50] Advocates of net neutrality criticized the changes.[51]

FCC's authority narrowed (2014)

On January 14, 2014, the DC Circuit Court determined in the case of Verizon Communications Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission[52] that the FCC has no authority to enforce Network Neutrality rules, since service providers are not identified as "common carriers".[53] The court agreed that FCC can regulate broadband and may craft more specific rules that stop short of identifying service providers as common carriers.[54]

Section 706 vs. Title II

As a response to the DC Circuit Court's decision, a dispute developed as to whether net neutrality could be guaranteed under existing law, or if reclassification of ISPs was needed to ensure net neutrality.[55] Wheeler stated that the FCC had the authority under Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 to regulate ISPs, while others, including President Obama,[56] supported reclassifying ISPs as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. Critics of Section 706 point out that the section has no clear mandate to guarantee equal access to content provided over the internet, while subsection 202(a) of the Communications Act states that common carriers cannot "make any unjust or unreasonable discrimination in charges, practices, classifications, regulations, facilities, or services." Advocates of net neutrality have generally supported reclassifying ISPs under Title II, while FCC leadership and ISPs have generally opposed such reclassification. The FCC stated that if they reclassified ISPs as common carriers, the commission would selectively enforce Title II, so that only sections relating to broadband would apply to ISPs.[55]

Deliberations about reclassification as common carriers (2014-2015)

Policy proposals (2014)

On February 19, 2014 the FCC announced plans to formulate new rules to enforce net neutrality while complying with the court rulings.[58] However, in the event, on April 23, 2014, the FCC reported a new draft rule that would permit broadband ISPs such as Comcast and Verizon to offer content providers, such as Netflix, Disney or Google, willing to pay a higher price, faster connection speeds, so their customers would have preferential access, thus reversing its earlier position and (so far as opinion outside the ISP sector generally agreed) would deny net neutrality.[9][59][60][61][62]

Public response was heated, pointing out FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler's past as a President and CEO of two major ISP-related organizations, and the suspicion of bias towards the profit-motives of ISPs as a result. Shortly afterwards, during late April 2014, the contours of a document leaked that indicated that the FCC under Wheeler would consider promulgating rules allowing Internet service providers (ISPs) to violate net neutrality principles by making it easier for Internet users to access certain content — whose owners paid fees to the ISPs (including cable companies and wireless ISPs) — and harder to access other content,[63] thus undermining the traditional open architecture of the Internet. These plans received substantial backlash from activists, the mainstream press, and some other FCC commissioners.[64][65] In May 2014, over 100 Internet companies — including Google, Microsoft, eBay, and Facebook — signed a letter to Wheeler voicing their disagreement with his plans, saying they represented a "grave threat to the Internet".[66] As of May 15, 2014, the "Internet fast lane" rules passed with a 3–2 vote. They were then open to public discussion that ended July 2014.[67]

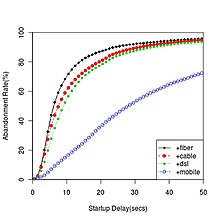

On May 15, 2014, in the face of continuing intense focus and criticism, the FCC stated it would consider two options regarding Internet services: first, permit fast and slow broadband lanes, thereby compromising net neutrality; and second, reclassify broadband as a telecommunication service, thereby preserving net neutrality.[10][68] The same day, the FCC opened a public comment period on how FCC rulemaking could best protect and promote an open Internet, garnering over one million responses, the most the FCC had ever received for rulemaking.[69] The FCC proposal for a tiered Internet received heavy criticism. Opponents argued that a user accessing content over the "fast lane" on the Internet would find the "slow lane" intolerable in comparison, greatly disadvantaging any content provider who is unable to pay for "fast lane" access. They argued that a tiered Internet would suppress new Internet innovations by increasing the barrier to entry. Video providers Netflix[70] and Vimeo[71] in their comments filed with the FCC used the research of S.S. Krishnan and Ramesh Sitaraman that provided quantitative evidence of the impact of Internet speed on online video users.[57] Their research studied the patience level of millions of Internet video users who waited for a slow-loading video to start playing. Users with faster Internet connectivity, such as fiber-to-the-home, demonstrated less patience and abandoned their videos sooner than similar users with slower Internet connectivity.[72][73][74]

Opponents of the rules declared September 10, 2014 to be the "Internet Slowdown". Participating websites were purposely slowed down to show what they felt would happen if the new rules took effect. Websites that participated in the Internet Slowdown included Netflix,[75] Reddit, Tumblr, Twitter, Vimeo and Kickstarter.[76][77][78][79] The Economist described the "Battle for the Net [...] now casting the upcoming FCC decision as an epic clash between "Team Internet" (a plucky band of high-tech multi-millionaires) and "Team Cable" (a dastardly bunch of Big-ISP billionaires)."[80] On November 10, 2014, President Obama stepped in, and recommended the FCC reclassify broadband Internet service as a telecommunications service in order to preserve net neutrality.[11][81][82]

Ruling

On January 16, 2015, Republicans presented legislation, in the form of a U. S. Congress HR discussion draft bill, that made concessions to net neutrality but prohibited the FCC from accomplishing that goal, or from enacting any further regulation affecting ISPs.[12][83] Two weeks later, on January 31, AP News reported the FCC would present the notion of applying ("with some caveats") common carrier status to the internet in a vote expected on February 26, 2015.[84][85][86][87][88] Adoption of this notion would reclassify internet service from one of information to one of telecommunications[89] and ensure net neutrality, according to FCC chairman Tom Wheeler.[90][91] On the day before the FCC vote, the FCC was expected to vote to regulate the Internet in this manner, as a public good,[13][14] and on February 26, 2015 the FCC voted to apply common carrier of the Communications Act of 1934 and Section 706 of the Telecommunications act of 1996 to the internet.[2][3][4][13][14] On the same day, the FCC also voted to preempt state laws in North Carolina and Tennessee that limited the ability of local governments in those states to provide broadband services to potential customers outside of their service areas. While the latter ruling affects only those two states, the FCC indicated that the agency would make similar rulings if it received petitions from localities in other states.[92] In response to ISP and opponent views, the FCC chairman, Tom Wheeler, commented, "This is no more a plan to regulate the Internet than the First Amendment is a plan to regulate free speech. They both stand for the same concept."[93]

On March 12, 2015, the FCC released the specific details of its new net neutrality rules,[94][95][96] and on April 13, 2015, the final rule was published.[15][16]

Social media platforms had a large role on engaging the public in the debate surrounding net neutrality. Popular websites such as Tumblr, Vimeo, and Reddit also participated in the “internet slowdown” on September 10, 2014, which the organization said was the largest sustained (lasting more than a single day) online protest effort in history.[97] On January 26, 2015 popular blogging site Tumblr placed links to group Fight For The Future, a net neutrality advocacy group. The website displayed a countdown to the FCC vote on Title II on February 26, 2015. This was part of a widespread internet campaign to sway congressional opinion and encourage users to call or submit comments to congressional representatives.[98] Net neutrality advocacy groups such as Save the Internet coalition[99] and Battle for the Net[100] responded to the 2015 FCC ruling by calling for defense of the new net neutrality rules.[99]

Timeline of significant events

January 12, 2003 - Law Professor Tim Wu coins phrase Net Neutrality while discussing “competing contents and applications.” [101]

June 27, 2005 - Supreme Court decides that “communications, content, and applications are allowed to pass freely over the Internet's broadband pipes”[102]

September 1, 2007 - “Comcast begins interfering with Bittorrent traffic on its network.”

January 9, 2008 - FCC investigates Comcast traffic policy and treatment of Bittorrent traffic [103]

August 9, 2010 - Google and Verizon try to cut deal to make larger parts of internet to be exempt from protection from the net neutrality rules from the FCC [104]

December 21, 2010 - FCC creates “Open Internet Rules” which “established high-level rules requiring transparency and prohibiting blocking and unreasonable discrimination to protect Internet openness”.

September 23, 2011 - The Federal Register publishes the Open Internet Rules[105]

May 13, 2014 - FCC releases new proposal including new rules on allowing “fast lanes and slow lanes online”[106]

June 13, 2014 - FCC investigates large companies such as Netflix for interconnection policies [107]

July 15, 2014 - FCC opens up on Public Knowledge for public comments, received 1.1 millions comments on the first day. Determined that "less than 1% of comments were clearly opposed to net neutrality." [108] [109]

September 15, 2014 - FCC receives 3.7 million comments in total. “The FCC's server crashes again as millions more people, companies, and advocacy organizations weigh in on the open internet rules.”

February 26, 2015 - FCC passes the Title II Net Neutrality Rules. “In a 3-2 party-line vote, the FCC passes open internet rules applying to both wired and wireless internet connections grounded in Title II authority.” [110]

June 12, 2015 - Net neutrality rules go into effect.[111]

June 14, 2016 - New rules are upheld by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.[112]

Violations

Many broadband operators imposed various contractual limits on the activities of their subscribers. In the best known examples, Cox Cable disciplined users of virtual private networks (VPNs) and AT&T, as a cable operator, warned customers that using a Wi-Fi service for home-networking constituted "theft of service" and a federal crime.[113] Comcast blocked ports of VPNs, forcing the state of Washington, for example, to contract with telecommunications providers to ensure that its employees had access to unimpeded broadband for telecommuting applications. These early instances of "broadband discrimination" prompted both academic and government responses. Other broadband providers proposed to start charging service and content providers in return for higher levels of service (higher network priority, faster or more predictable), creating what is known as a tiered Internet. Packets originating from providers who pay the additional fees would in some fashion be given better than "neutral" handling, accelerated or more reliable handling of selected packets.[citation needed]

In 2007 it was discovered that Comcast was blocking people from sharing digital files of the King James Bible and public-domain song recordings.[114]

In April 2012, the CEO of Netflix criticized Comcast for not "following net neutrality principles". Netflix charged that Comcast was restricting access to popular online video sites, in order to promote Comcast's own Xfinity TV service. The criticism followed similar comments from Washington, D.C.-based consumer group Free Press, which said that Comcast's policies gave "the Comcast product an unfair advantage against other Internet video services".[115]

In September 2012, a group of public interest organizations such as Free Press, "Public Knowledge" and the "New American Foundation's Open Technology Institute" filed a complaint with the FCC that AT&T was violating net-neutrality rules by restricting use of Apple's video-conferencing application "FaceTime" to certain customers. The application could formerly be used over Wi-Fi signals was suddenly restricted to cellular connection and customers with a shared data plan on AT&T, excluding those with older unlimited or tiered data plans.[116]

Broadband providers can block common service ports, such as port 25 (SMTP) or port 80 (HTTP), preventing consumers (and botnets) from hosting web and email servers unless they upgrade to a "business" account.[citation needed]

Contrary to transporting all data equally (as long as it is legal) regardless of what kind of data or who it is from and to, Charter Communications's rules say all internet users without a commercial account (aka another class of user or fast lane) are not allowed to: "[Run] any type of server on the system that is not consistent with personal, residential use. This includes but is not limited to FTP, IRC, SMTP, POP, HTTP, SOCS, SQUID, NTP, DNS or any multi-user forums."[117]

Attempted legislation

Arguments associated with net neutrality regulations came into prominence in mid-2002, offered by the "High Tech Broadband Coalition", a group comprising the Business Software Alliance; the Consumer Electronics Association; the Information Technology Industry Council; the National Association of Manufacturers; the Semiconductor Industry Association; and the Telecommunications Industry Association, some of which were developers for Amazon.com, Google, and Microsoft. The full concept of "net neutrality" was developed by regulators and legal academics, most prominently law professors Tim Wu, Lawrence Lessig and Federal Communications Commission Chairman Michael Powell often while speaking at the University of Colorado School of Law Annual Digital Broadband Migration conference or writing in Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law.[118]

By late 2005, several Congressional draft bills contained net neutrality regulations, as a part of ongoing proposals to reform the Telecommunications Act of 1996, requiring Internet providers to allow consumers access to any application, content, or service. However, important exceptions have permitted providers to discriminate for security purposes, or to offer specialized services like "broadband video" service.[citation needed]

In April 2006, a large coalition of public interest, consumer rights and free speech advocacy groups and thousands of bloggers—such as Free Press, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, American Library Association, Christian Coalition of America, Consumers Union, Common Cause and MoveOn.org—launched the SavetheInternet.com Coalition, a broad-based initiative working to "ensure that Congress passes no telecommunications legislation without meaningful and enforceable network neutrality protections." Within two months of its establishment, it delivered over 1,000,000 signatures to Congress in favor of net neutrality policies and by the end of 2006, it had collected more than 1.5 million signatures.[citation needed]

Two proposed versions of "neutrality" legislation were to prohibit: (1) the "tiering" of broadband through sale of voice- or video-oriented "Quality of Service" packages; and (2) content- or service-sensitive blocking or censorship on the part of broadband carriers. These bills were sponsored by Representatives Markey, Sensenbrenner, et al., and Senators Snowe, Dorgan, and Wyden.

In 2006 Congressman Adam Schiff (D-California), one of the Democrats who voted for the 2006 Sensenbrenner-Conyers bill, said: "I think the bill is a blunt instrument, and yet I think it does send a message that it's important to attain jurisdiction for the Justice Department and for antitrust issues."[119] Net neutrality bills were referred to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, whose Committee Chair until 2014, Jay Rockefeller (D-West Virginia) had expressed caution about introducing unnecessary legislation that could tamper with market forces.[citation needed]

The following legislative proposals have been introduced in Congress to address the net neutrality question:

| Title | Bill number | Date introduced | Sponsors | Provisions | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109th Congress of the United States (January 2005 – January 2007) | |||||

| Internet Freedom and Nondiscrimination Act of 2006[120][121] | S. 2360 | March 2, 2006 | Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon) |

|

Killed by the end of 109th Congress. |

| Communications Opportunity, Promotion and Enhancement Bill of 2006[123][124][125] | H.R. 5252 | March 30, 2006 | Representative Joe Barton (R-Texas and Chairman of the House Commerce Committee) |

|

Passed 321–101 by the full House of Representatives on June 8, 2006– but with the Network Neutrality provisions of the Markey Amendment removed. Bill killed by end of 109th Congress.[128] |

| Network Neutrality Act of 2006[129] | H.R. 5273 | April 3, 2006 | Representative Ed Markey (D-Massachusetts) |

|

Defeated 34–22 in committee with Republicans and some Democrats opposing, most Democrats supporting.[130] |

| Communications Opportunity, Promotion and Enhancement Bill of 2006[131] | S. 2686 | May 1, 2006 | Senators Ted Stevens (R-Alaska) & Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii) | Aims to amend the Communications Act of 1934 and addresses net neutrality by directing the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to conduct a study of abusive business practices predicted by the Save the Internet coalition and similar groups. | Sent to Senate in a 15–7 committee vote and defeated by the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, & Transportation on June 28, 2006. Killed by the end of 109th Congress. |

| Internet Freedom and Nondiscrimination Act of 2006[132] | H.R. 5417 | May 18, 2006 | Representatives Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wisconsin) & John Conyers (D-Michigan) |

|

Approved 20-13 by the House Judiciary committee on May 25, 2006. Killed by the end of 109th Congress. |

| 110th Congress of the United States (January 2007 – January 2009) | |||||

| Internet Freedom Preservation Act (casually known as the Snowe-Dorgan bill)[134] | S. 215 (110th Congress) formerly S. 2917 (109th Congress) | January 9, 2007 | Senators Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) & Byron Dorgan (D-North Dakota), Co-Sponsors: Barack Obama (D-Illinois), Hillary Clinton (D-New York), John Kerry (D-Massachusetts) and other Senators |

|

Read twice and referred to the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. |

| Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2008[136] | H.R.5353 | February 12, 2008 | Representatives Edward Markey (D-Massachusetts) & Charles Pickering (R-Mississippi) |

|

Introduced to the House Energy and Commerce Committee |

| 111th Congress of the United States (January 2009 – January 2011) | |||||

| Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009[138][139] | H.R.3458 | 2009 | – |

|

– |

| 112th Congress of the United States (January 2011 – January 2013) | |||||

| Data Cap Integrity Act of 2012[142] | S. 3703 | December 20, 2012 | Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon) | To improve the ability of consumers to control their digital data usage, promote Internet use, and for other purposes. | Read twice and referred to the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. |

| (D) = a member of the House or Senate Democratic Caucus; (R) = a member of the House or Senate Republican Conference | |||||

Positions

There has been extensive debate about whether net neutrality should be required by law in the United States. Debate over the issue predates the coining of the term. Advocates of net neutrality have raised concerns about the ability of broadband providers to use their last mile infrastructure to block Internet applications and content (e.g. websites, services, and protocols), and even to block out competitors.[143] While opponents claim net neutrality regulations would deter investment into improving broadband infrastructure and try to fix something that isn't broken.[144][145]

Only a few U.S. technology trade associations and the U.S. financial sector were neutral as of 2006.[146][citation needed]

In 2014 Professor Susan Crawford, a legal and technology expert at Harvard Law School suggested that municipal broadband might be a possible solution to net neutrality concerns.[147]

Support of net neutrality

Organizations that support net neutrality come from widely varied political backgrounds and include groups such as MoveOn.org, Free Press, Consumer Federation of America, AARP, American Library Association, Gun Owners of America, Public Knowledge, the Media Access Project, the Christian Coalition, and TechNet.[148][149][150] Tim Berners-Lee (the inventor of the World Wide Web) has also spoken out in favor of net neutrality.[151] In May 2014, some websites admitted to inserting code that slowed access to their site by users from known FCC IP addresses, as a protest on the FCC's position on net neutrality.[152]

Proponents of net neutrality, in particular those in favor of reclassification of broadband to "common carrier", have many concerns about the potential for discriminatory service on the part of providers such as Comcast. Common-carriage principles require network operators to serve the public regardless of geographical location, district income levels, or usage. Telecommunications companies are required to provide services, such as phone access, to all consumers on the premise that it is a necessity that should be available to all people equally. If the FCC's ability to regulate this aspect is removed, providers could cease to offer services to low income neighborhoods or rural environments. Those in favor of net neutrality often cite that the internet is now an educational necessity, and as such should not be doled out at the discrimination of private companies, whose profit-oriented models cause a conflict of interest.

Outside of the US several countries have removed net neutrality protocols and have started double charging for delivering content (once to consumer and again to content providers). This equates to a toll being required for certain internet access, essentially limiting what is available to all people, in particular low income households.[153]

Large already well established companies may not be hurt by the cost increase that providers such as Comcast intend to levy upon them, but it would permanently stifle small businesses and the internet's ability to encourage start-ups.[154] Many have pointed out that sites such as Facebook, Google, and Amazon would not have been able to survive if net neutrality hadn't been in place.[155] Concerns abound as to what kind of long term damage would be inflicted on future website innovations, including educational content such as MIT's OpenCourseWare which is a free website offering online video lectures to the public.[156]

Internet was created to be a free and open exchange.”[157]

For Conti, he sees the children's education is at stake and that lessons that incorporate the use of the internet are under risk since charter schools like Conti and public schools may not afford the Internet and in additions families may not be able to afford Internet at home for their children's educational needs. Students from virtual charter schools, public schools, children with special needs and homeschool children all depend mostly on web instructions, according to Charamonte.[157]

Barbara Stripling, the president American Library Association stated that “An open Internet is essential to our nation’s educational achievement, freedom of speech and economic growth,”[157] According to Barbara, “School, public and college libraries rely upon the public availability of open, affordable Internet access for school homework assignments, distance learning classes, e-government services, licensed databases, job-training videos, medical and scientific research, and many other essential services, we must ensure the same quality access to online educational content as to entertainment and other commercial offerings.”[157]

Not all net neutrality proponents emphasize transparency to customers, and most proponents do not phrase net neutrality in terms of existing telecom carrier restrictions even when the desired state is equivalent.[citation needed] In many cases, a return to treating Internet service links as telecommunication rather than information carrier services would re-invoke sufficient restrictions on discrimination and refusal to carry to satisfy most definitions of net neutrality and would return carriers to the conditions of limited liability that were in part breached by the 2005 FCC decision that DSL services are information services, and thus not subject to common carrier rules.[citation needed]

Previously existing FCC rules do not prevent telecommunications companies from charging fees to certain content providers in exchange for preferential treatment (the so-called "fast lanes"). Neutrality advocates Tim Wu and Lawrence Lessig have argued that the FCC does have regulatory power over the matter, following from the must-carry precedent set in the Supreme Court case Turner Broadcasting v. Federal Communications Commission.[158]

Net neutrality proponents claim that telecom companies seek to impose a tiered service model in order to control the pipeline and thereby remove competition, create artificial scarcity, and oblige subscribers to buy their otherwise noncompetitive services.[159] Many believe net neutrality to be primarily important for the preservation of current internet freedoms; a lack of net neutrality would allow Internet service providers, such as Comcast, to extract payment from content providers like Netflix, and these charges would ultimately be passed on to consumers.[160][161] Prominent supporters of net neutrality include Vinton Cerf, co-inventor of the Internet Protocol, Tim Berners-Lee, creator of the Web, law professor Tim Wu, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, Tumblr founder David Karp, and Last Week Tonight host John Oliver.[162][163][164][165] Organizations and companies that support net neutrality include the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Greenpeace, Tumblr, Kickstarter, Vimeo, Wikia, Mozilla Foundation, and others.[159][166][167][168]

Opposition to net neutrality

Opponents argue that (1) net neutrality regulations severely limit the Internet's usefulness; (2) net neutrality regulations threaten to set a precedent for even more intrusive regulation of the Internet; (3) imposing such regulation will chill investment in competitive networks (e.g., wireless broadband) and deny network providers the ability to differentiate their services; and (4) that network neutrality regulations confuse the unregulated Internet with the highly regulated telecom lines that it has shared with voice and cable customers for most of its history;[citation needed] (5) net neutrality would benefit industry lobbyists, and not consumers due to the potential of regulatory capture with policies that protect incumbent interests.[169]

Organizations opposing net neutrality are the free-market advocacy organizations FreedomWorks Foundation,[170] Americans for Prosperity, the National Black Chamber of Commerce, LULAC, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, the Progress and Freedom Foundation and high-tech trade groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.[citation needed] For example, former hedge fund manager turned journalist Andy Kessler has argued, the threat of eminent domain against the telecommunication providers, instead of new legislation, is the best approach by forcing competition and better services.[171] The Communications Workers of America, the largest union representing installers and maintainers of telecommunications infrastructure, opposes the regulations.

A number of net neutrality opponents have created a website called Hands Off The Internet[citation needed] to explain their arguments against net neutrality. Principal financial support for the website comes from AT&T, and members include technology firms such as Alcatel, 3M and pro-market advocacy group Citizens Against Government Waste.[172][173][174][175] Many conspiracy theorists allege corporate astroturfing.[172] For example, one print ad seems to frame the Hands Off the Internet message in pro-consumer terms. "Net neutrality means consumers will be stuck paying more for their Internet access to cover the big online companies' share," the ad claims.[176]

In November 2005 Edward Whitacre, Jr., then chief executive officer of SBC Communications, stated "there's going to have to be some mechanism for these [Internet upstarts] who use these pipes to pay for the portion they're using", and that "The Internet can't be free in that sense, because we and the cable companies have made an investment,"[177] sparking a furious debate. SBC spokesman Michael Balmoris said that Whitacre was misinterpreted and his comments only referred to new tiered services.[178]

Net neutrality laws are generally opposed by the cable television and telephone industries, and some network engineers and free-market scholars from the conservative to libertarian, including Christopher Yoo and Adam Thierer.[citation needed]

Net neutrality opponents such as IBM, Intel, Juniper, Qualcomm, and Cisco claim that net neutrality would deter investment into broadband infrastructure, saying that "shifting to Title II means that instead of billions of broadband investment driving other sectors of the economy forward, any reduction in this spending will stifle growth across the entire economy. Title II is going to lead to a slowdown, if not a hold, in broadband build out, because if you don’t know that you can recover on your investment, you won’t make it."[144][179] Others argue that the regulation is "a solution that won’t work to a problem that simply doesn’t exist".[180] Prominent opponents also include Netscape founder and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, co-inventor of the Internet Protocol Bob Kahn, PayPal founder and Facebook investor Peter Thiel, MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte, Internet engineer and former Chief Technologist for the FCC David Farber, VOIP pioneer Jeff Pulver and Nobel Prize economist Gary Becker.[181][182][183][184][185] Organizations and companies that oppose net neutrality regulations include several major technology hardware companies, cable and telecommunications companies, hundreds of small internet service providers, various think tanks, several civil rights groups, and others.[144][186][187][188][189]

Critics of net neutrality argue that data discrimination is desirable for reasons like guaranteeing quality of service. Bob Kahn, co-inventor of the Internet Protocol, called the term net neutrality a slogan and opposes establishing it, but he admits that he is against the fragmentation of the net whenever this becomes excluding to other participants.[181] Vint Cerf, Kahn's co-founder of the Internet Protocol, explains the confusion over their positions on net neutrality, "There’s also some argument that says, well you have to treat every packet the same. That’s not what any of us said. Or you can’t charge more for more usage. We didn’t say that either."[190]

Alternative FCC proposals

An alternate position was proposed in 2010 by then-FCC Commissioner Julius Genachowski, which would narrowly reclassify Internet access as a telecommunication service under Title Two of the Communications Act of 1934. It would apply only six[191] common carrier rules under the legal principle of forbearance that would sufficiently prevent unreasonable discrimination and mandate reasonable net neutrality policies under the concept of common carriage. Incumbent ISP AT&T opposed the idea saying that common carrier regulations would "cram today's broadband Internet access providers into an ill-fitting 20th century regulatory silo" while Google supported the FCC proposal "In particular, the Third Way will promote legal certainty and regulatory predictability to spur investment, ensure that the Commission can fulfill the tremendous promise of the National Broadband Plan, and make it possible for the Commission to protect and serve all broadband users, including through meaningful enforcement".[192]

In October 2014, after the initial proposal was shot down, the FCC began drafting a new proposal that would take a hybrid regulatory approach to the issue. Although this alternative has not yet been circulated, it is said to propose that there be a divide between "wholesale" and "retail" transactions.[193] In order to illustrate clear rules that are grounded by law, reclassification of Title II of the Communications Act of 1934 will be involved as well as parts of Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Data being sent between content provider and ISPs will involve stricter regulations compared to transactions between ISP's and consumers, which will involve more lax parameters. Restrictions on offering a data fast lane will be enforced between content providers and ISPs to avoid unfair advantages. This hybrid proposal has become the most popular solution among the three options that FCC has reported. However, ISPs, such as AT&T who has already warned the public via tweet "any use of Title II would be problematic", are expected to dispute this solution.[193] The official proposal was rumored to become public by the end of 2014.[194]

Opinions cautioning against legislation

In 2006 Bram Cohen, the creator of BitTorrent, said "I most definitely do not want the Internet to become like television where there's actual censorship... however it is very difficult to actually create network neutrality laws which don't result in an absurdity, like making it so that ISPs can't drop spam or stop... attacks."[195]

In June 2007, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) urged restraint with respect to new regulations proposed by net neutrality advocates, noting the "broadband industry is a relatively young and evolving one," and given no "significant market failure or demonstrated consumer harm from conduct by broadband providers" such regulations "may well have adverse effects on consumer welfare, despite the good intentions of their proponents."[196] The FTC conclusions were questioned in Congress in September 2007, when Sen. Byron Dorgan, D-N.D., chairman of the Senate interstate commerce, trade and tourism subcommittee, told FTC Chairwoman Deborah Platt Majoras that he feared new services as groundbreaking as Google could not get started in a system with price discrimination.[197]

In 2011 Aparna Watal, a legal officer at an Internet company named Attomic Labs, has put forward three points for resisting any urge "to react legislatively to the apparent regulatory crisis".[198] Firstly, "contrary to the general opinion, the Comcast decision does not uproot the Commission's authority to regulate ISPs. Section 201(b) of the Act, which was cited as an argument by the Commission but not addressed by the Court on procedural grounds, could grant the Commission authority to regulate broadband Internet services where they render "charges, practices and regulations for, and in connection with" common carrier services unjust and unreasonable."[198] Secondly, she suggests, it is "undesirable and premature to legislatively mandate network neutrality or for the Commission to adopt a paternalistic approach on the issue ... [as] there have been few overt incidents to date, and the costs of those incidents to consumers have been limited."[198] She cites "prompt media attention and public backlash" as effective policing tools to prevent ISPs from throttling traffic. She suggests that it "would be more prudent to consider introducing modest consumer protection rules, such as requiring ISPs to disclose their network management practices and to allow for consumers to switch ISPs inexpensively, rather than introducing network neutrality laws."[198] "While by regulating broadband services the commission is not directly regulating content and applications on the Internet", content will be affected by the reclassification. "The different layers of the Internet work in tandem with each other such that there is no possibility of throttling or improving one layer's performance without impacting the other layers. ... To let the Commission regulate broadband pipelines connecting to the Internet and disregard that it indirectly involves regulating the data that runs through them will lead to a complex, overlapping, and fractured regulatory landscape in the years to come."[198]

Unresolved issues

The Internet is a highly federated environment composed of thousands of carriers, many millions of content providers and more than a billion end users – consumers and businesses. Prioritizing packets is complicated even if both the content originator and the content consumer use the same carrier.[citation needed] It is much less reliable if the packets have to traverse multiple carrier networks, because the packet getting "premium" service while traversing network A may drop down to non-premium service levels in network B.[citation needed]

As of 2006 the debate over "neutrality" did not yet capture some dimensions of the topic; for example, if voice packets should get higher priority than packets carrying email or if emergency services, mission-critical, or life-saving applications, such as tele-medicine, should get priority over spam.[199] The discussion is terrestrial-network centered, even though the Internet is inherently global and mobility is the fastest growing source of new demand.[citation needed]

Alternatives to cable and DSL

Much of the push for network neutrality rules comes from the lack of competition in broadband services. For that reason, municipal wireless and other wireless service providers are highly relevant to the debate. If successful, such services would provide a third type of broadband access with the potential to change the competitive landscape. For similar reasons, the feasibility of broadband over powerline services is also important to the network neutrality issue. However, as of spring of 2006, deployments beyond cable and DSL service have created little new competition.[citation needed][needs update]

In response, cable companies have lobbied Congress for a federal preemption to ban states and municipalities from competing and thereby interfering with interstate commerce. However, there is current Supreme Court precedent for an exception to the Commerce Power of Congress for states as states going into business for their citizens.

In 2006 it has been proposed that neither municipal wireless nor other technological solutions such as encryption, onion routing, or time-shifting DVR would be sufficient to render possible discrimination moot.[200]

3GPP cellular networks provide a practical broadband alternative known as EVDO, which, along with WiMax, represents a fourth and fifth alternative. The latter has been deployed in limited areas, but 3GPP in much wider ones.

Utility company restrictions

EPB, the municipal utility serving Chattanooga, Tennessee, petitioned the FCC to allow them to deliver internet to communities outside of the 600-square mile area that they service.[201] A similar petition was made by Wilson, North Carolina. According to FCC officials, some residents who lived just outside the service areas of the Chattanooga and Wilson utilities then had no broadband service available.[92] One of the two February 26, 2015 rulings set aside those states' restrictions on municipal broadband, although legal challenges to the FCC's authority to do so were seen as likely.[92] At the time of the ruling, 19 U.S. states had laws that made it difficult or impossible for utility companies to deliver Internet outside of the area that they service.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (April 8, 2011). "House Votes Against 'Net Neutrality'". New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c Staff (February 26, 2015). "FCC Adopts Strong, Sustainable Rules To Protect The Open Internet" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Ruiz, Rebecca R.; Lohr, Steve (February 26, 2015). "In Net Neutrality Victory, F.C.C. Classifies Broadband Internet Service as a Public Utility". New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Flaherty, Anne (February 25, 2015). "FACT CHECK: Talking heads skew 'net neutrality' debate". AP News. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Osipova, Natalia (May 15, 2014). "How Net Neutrality Works". New York Times.

- ^ "AT&T, Comcast Rout Google, Microsoft in Net Neutrality Battle". Bloomberg News. July 20, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ^ "Bill Text – 109th Congress (2005–2006) – THOMAS (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Dolasia, Merra (February 12, 2014). "The Debate about Net Neutrality and Why We Should Care". DOGO News.

- ^ a b Wyatt, Edward (April 23, 2014). "F.C.C., in 'Net Neutrality' Turnaround, Plans to Allow Fast Lane". New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Staff (May 15, 2014). "Searching for Fairness on the Internet". New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Wyatt, Edward (November 10, 2014). "Obama Asks F.C.C. to Adopt Tough Net Neutrality Rules". New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Weisman, Jonathan (January 19, 2015). "Shifting Politics of Net Neutrality Debate Ahead of F.C.C.Vote". New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c Weisman, Jonathan (February 24, 2015). "As Republicans Concede, F.C.C. Is Expected to Enforce Net Neutrality". New York Times. CNBC. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Lohr, Steve (February 25, 2015). "The Push for Net Neutrality Arose From Lack of Choice". New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Reisinger, Don (April 13, 2015). "Net neutrality rules get published -- let the lawsuits begin". CNET. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ a b Federal Communications Commission (April 13, 2015). "Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet - A Rule by the Federal Communications Commission on 04/13/2015". Federal Register. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Open Internet - FCC.gov". fcc.gov. Federal Communications Commission.

- ^ Mark S. Fowler and Daniel L. Brenner, A Marketplace Approach to Broadcast Regulation, 60 Texas L. Rev. 207 (1982) is the definitive statement of this by the FCC chairman at the time, but this theory has been worked out extensively since.

- ^ "Remarks as Delivered". Artcontext. January 11, 1994. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Jan Krämer, Lukas Wiewiorra, Christof Weinhardt, Net Neutrality in the United States and Europe, CPI Antitrust Chronicle, March 2012(2)

- ^ Powell, Michael (February 8, 2004). "Preserving Internet Freedom: Guiding Principles for the Industry" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ "In the Matter of Madison River Communications, LLC and affiliated companies" (PDF). Consent Decree DA 05-543. FCC. 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ United States Court of Appeals. "No. 00-1012" (PDF).

- ^ Federal Communications Commission (August 5, 2005). "New Principles Preserve and Promote the Open and Interconnected Nature of Public Internet" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ "Before the Federal Communications Commission" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Isenberg, David (August 7, 2005). "How Martin's FCC is different from Powell's". Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ "Policy statement" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Re : Notice of Ex Parte Communication in the Matter of Review of AT&T Inc . and BellSouth Corp Application For Consent to Transfer of Control, WC Docket No. 06-74" (PDF). Federal Communications Commissions. December 28, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Cheng, Jacqui (October 19, 2007). "Evidence mounts that comcast is targeting Bittorrent Traffic". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ Ernesto (August 17, 2007). "Comcast Throttles BitTorrent Traffic, Seeding Impossible". TorrentFreak. TorrentFreak BV. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ Kumar, Vishesh (March 27, 2008). "Comcast, BitTorrent reached an agreement to work together on network traffic". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Duncan, Geoff (December 23, 2009). "Comcast to Pay $16 Million for Blocking P2P Applications". Digital Trends. Retrieved December 23, 2009.

- ^ Cheng, Jacqui (December 22, 2009). "Comcast settles P2P throttling class-action for $16 million". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved December 23, 2009.

- ^ "THE FCC TACKLES NET NEUTRALITY: AGENCY JURISDICTION AND THE COMCAST ORDER" (PDF). Berkley Technology Law Journal. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Toy-safety bill advances, No to Internet rationing". The Week. August 8, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Kathleen Ann Ruane (February 20, 2009). "Net Neutrality: The Federal Communications Commission's Authority to Enforce its Network Management Principles" (PDF). Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ Hansell, Saul (August 2, 2008). "F.C.C. Vote Sets Precedent on Unfettered Web Usage". New York Times.

- ^ "VOIP over cellular connections".

- ^ Nate Anderson (September 21, 2009). "FCC Chairman wants network neutrality, wired and wireless". Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ Tim Greene (October 22, 2009). "FAQ: What's the FCC vote on net neutrality all about?".

- ^ Gross, Grant (April 6, 2010). "Court rules against FCC's Comcast net neutrality decision". Reuters. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan (April 6, 2010). "Court: FCC has no power to regulate Net neutrality". CNET.

- ^ Ann Ruane, Kathleen (April 29, 2013). "The FCC's Authority to Regulate Net Neutrality After Comcast v. FCC" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Matthew Lasar (May 5, 2010). "FCC on net neutrality: yes we can". arstechnica.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "FCC says will act on Web neutrality if needed". Reuters. February 25, 2008.

- ^ "Google Intends to Bid in Spectrum Auction If FCC Adopts Consumer Choice and Competition Requirements". Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "FCC sets 700 MHz auction rules: limited open access, no wholesale requirement". July 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Gustin, Sam (December 21, 2010). "FCC Passes Compromise Net Neutrality Rules". Wired.

- ^ Bartash, Jeffry (December 22, 2010). "FCC adopts web rules". MarketWatch. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ "FCC Adopts Net Neutrality Rules". Care2.com. December 21, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Kang, Cecilia (December 22, 2010). "FCC Approves Net-Neutrality Rules; Criticism is Immediate". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ^ Full text of decision and correction

- ^ Robertson, Adi. "Federal court strikes down FCC net neutrality rules". The Verge. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon. "Net neutrality is half-dead: Court strikes down FCC's anti-blocking rule". Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Berkman, Fran (May 20, 2014). "Title II is the key to net neutrality—so what is it?". The Daily Dot. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (November 10, 2014). "Obama Asks F.C.C. to Adopt Tough Net Neutrality Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Krishnan, S. Shunmuga; Sitaraman, Ramesh K. (November 2012). "Video Stream Quality Impacts Viewer Behavior" (PDF). University of Massachusetts. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ Nancy Weil (February 19, 2014). "FCC will set new net neutrality rules". Computerworld. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Staff (April 24, 2014). "Creating a Two-Speed Internet". New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Carr, David (May 11, 2014). "Warnings Along F.C.C.'s Fast Lane". New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (April 23, 2014), In Policy Shift, F.C.C. Will Allow a Web Fast Lane, Washington, DC, retrieved April 23, 2014

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nagesh, Gautham (April 23, 2014), FCC to Propose New 'Net Neutrality' Rules: Proposal Would Allow Broadband Providers to Give Preferential Treatment to Some Traffic, Washington, DC: Wall Street Journal, retrieved April 23, 2014

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (April 23, 2014). "F.C.C., in a shift, backs fast lanes for web traffic". New York Times. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Hattem, Julian (April 25, 2014). "NYT blasts net neutrality proposal". The Hill. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Gustin, Sam (May 7, 2014). "Net Neutrality: FCC Boss Smacked by Tech Giants, Internal Dissent". TIME. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Nagesh, Gautham (May 7, 2014). "Internet Companies, Two FCC Commissioners Disagree With Proposed Broadband Regulations". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Edwards, Haley Sweetland (May 15, 2014). "FCC Votes to Move Forward on Internet 'Fast Lane'". Time. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Wyatt, Edward (May 15, 2014). "F.C.C. Backs Opening Net Rules for Debate". New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Hu, Elise (July 21, 2014). "1 Million Net Neutrality Comments Filed, But Will They Matter?". National Public Radio. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "NetFlix comments to FCC, page 17, Sept 16th 2014".

- ^ "Vimeo Open Letter to FCC, page 11, July 15th 2014" (PDF).

- ^ "Patience is a Network Effect, by Nicholas Carr, Nov 2012".

- ^ "NPR Morning Edition: In Video-Streaming Rat Race, Fast is Never Fast Enough, October 2012". Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ Christopher Muther (February 2, 2013). "Instant gratification is making us perpetually impatient". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ Rose Eveleth (September 10, 2014). "Why Netflix Is 'Slowing Down' Its Website Today". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Fight for the Future. "Join the Battle for Net Neutrality". Battle for the Net. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Samuel Gibbs. "Battle for the net: why is my internet slow today?". the Guardian. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ The Christian Science Monitor. "Internet Slowdown Day: Why websites feel sluggish today (+video)". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Sharon Gaudin (September 10, 2014). "Internet Slowdown Day becomes an online picket protest". Computerworld. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ M.H. (September 10, 2014). "Net neutrality: Faux go-slow". The Economist. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ NYT Editorial Board (November 14, 2014). "Why the F.C.C. Should Heed President Obama on Internet Regulation". New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ Sepulveda, Ambassador Daniel A. (January 21, 2015). "The World Is Watching Our Net Neutrality Debate, So Let's Get It Right". Wired (website). Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Staff (January 16, 2015). "H. R. _ 114th Congress, 1st Session [Discussion Draft] – To amend the Communications Act of 1934 to ensure Internet openness..." (PDF). U. S. Congress. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (February 2, 2015). "In Net Neutrality Push, F.C.C. Is Expected to Propose Regulating Internet Service as a Utility". New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (February 2, 2015). "F.C.C. Chief Wants to Override State Laws Curbing Community Net Services". New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ Flaherty, Anne (January 31, 2015). "Just whose Internet is it? New federal rules may answer that". AP News. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Fung, Brian (January 2, 2015). "Get ready: The FCC says it will vote on net neutrality in February". Washington Post. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Staff (January 2, 2015). "FCC to vote next month on net neutrality rules". AP News. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (February 4, 2015). "F.C.C. Plans Strong Hand to Regulate the Internet". New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ Wheeler, Tom (February 4, 2015). "FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler: This Is How We Will Ensure Net Neutrality". Wired. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ The Editorial Board (February 6, 2015). "Courage and Good Sense at the F.C.C. – Net Neutrality's Wise New Rules". New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c Gross, Grant (February 26, 2015). "FCC votes to overturn state laws limiting municipal broadband". CIO Magazine. IDG News Service. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Liebelson, Dana (February 26, 2015). "Net Neutrality Prevails in Historic FCC Vote". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ Ruiz, Rebecca R. (March 12, 2015). "F.C.C. Sets Net Neutrality Rules". New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Sommer, Jeff (March 12, 2015). "What the Net Neutrality Rules Say". New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ FCC Staff (March 12, 2015). "Federal Communications Commission - FCC 15-24 - In the Matter of Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet - GN Docket No. 14-28 - Report and Order on Remand, Declaratory Ruling, and Order" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ "Sep 10th is the Internet Slowdown". Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ "Breaking: Grumpy Cat Soars over Comcast Headquarters to say "Don't Mess With The Internet"". Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "Save The Internet". Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ "Epic Victory at the FCC". Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ Tim Wu, "Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination", Columbia University Law School, 2003

- ^ Art Brodsky, "Public Knowledge Statement Regarding NCTA v BrandX Internet", Public Knowledge,June 27, 2005

- ^ Harold Feld, "Martin’s Big CES Announcement", Public Knowledge, January 9, 2008

- ^ John Bergmayer, "Theres only one internet", Public Knowledge, August 9, 2010

- ^ Harold Feld, "Quick Guide Upcoming Net Neutrality Rules Challenge", Public Knowledge, September 23, 2011

- ^ Michael Weinberg, "How the FCCs Proposed Fast Lanes Would Actually Work", Public Knowledge, May 13, 2014

- ^ Sam Gustin, "Netflix Pays Verizon in Streaming Deal", Time, April 28, 2014

- ^ Michael Weinberg, "Officially Explaining the Importance of an Open Internet", Public Knowledge, July 15, 2014

- ^ Bob Lannon, Andrew Pendelton, "What can we learn from 800000 Public Comments on the FCCs net Neutrality Plan", Sunlight Foundation, September 2, 2014

- ^ Michael Weinberg, "Landmark Day for Net Neutrality", Public Knowledge, September 15, 2014

- ^ FCC.gov, "Open Internet", FCC,

- ^ Alina Selyukh (June 14, 2016). "U.S. Appeals Court Upholds Net Neutrality Rules In Full". NPR.

- ^ NETWORK NEUTRALITY, BROADBAND DISCRIMINATION, Tim Wu Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law, Vol. 2, p. 141, 2003

- ^ Comcast Blocks Bible From Being Uploaded October 22, 2007 Fox News, Associated Press

- ^ Adario Strange (April 16, 2012). "Netflix CEO Attacks Comcast Over Net Neutrality Issues". PC Magazine. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Brian X. Chen (September 18, 2012). "Groups Prepare to Fight AT&T Over FaceTime Restrictions". The New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ Charter Services, then click "Residential Services Terms and Conditions" then click "Internet Acceptable Use Policy" (direct link is disabled)

- ^ Videos from the Digital Broadband Migration conference and papers from the Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law about Net Neutrality law are collected at http://neutralitylaw.com Archived March 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "House panel votes for Net neutrality". CNET News.com. May 25, 2006. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2006.

- ^ Wyden, Ron (March 2, 2006). "Wyden Moves to Ensure Fairness of Internet Usage with New Net Neutrality Bill". Archived from the original on June 28, 2006. Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ "IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES" (PDF). Public Knowledge. March 2, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Anonymous (March 2006). "Wyden Offers Bill to Bar Internet Discrimination". Telecommunications Reports (72): 27–28.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ U.S. Government Printing Office (May 15, 2006). "FULL TEXT of Communications Opportunity, Promotion and Enhancement Act of 2006 (H.R. 5252)" (PDF). Retrieved August 11, 2006.

- ^ Upton, Fred (March 30, 2006). "Upton Hearing Examines Bipartisan Bill that Will Bring Choice & Competition to Video Services". Archived from the original on July 2, 2006. Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h109-5252 H.R. 5252[109th]

- ^ a b c d Bagwell, Dana. "A First Amendment Case For Internet Broadband Network Neutrality". University of Washington. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ Barton, Joe (2006). Advanced Telecommunications and Opportunities Reform Act. 109th Congress (2005–2006) H.R.5252. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ "Huge Victory for Real People as Telco Bill Dies". Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- ^ a b Markey, Ed (April 3, 2006). "Markey Network Neutrality Amendment" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ http://clerk.house.gov/evs/2006/roll239.xml

- ^ Stevens, Ted (May 1, 2006). "Communications, Consumer's Choice, and Broadband Deployment Act of 2006" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ "To amend the Clayton Act with respect to competitive and nondiscriminatory access to the Internet" (PDF). Public Knowledge. May 18, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Sensenbrenner, James, Jr. "Internet Freedom and Nondiscrimination Act of 2006". 109th Congress (2005–2006) H.R.5417. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ U.S. Government Printing Office (January 9, 2007). "FULL TEXT of Internet Freedom Preservation Act (S. 215)" (PDF). Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Snowe, Olympia. "Internet Freedom Preservation Act". Internet Freedom Preservation Act (2006 (S.2917, 109th Congress) and 2007 (2.215, 110th Congress)). Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ Open Congress. "FULL TEXT of Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2008 (H.R.5353)". Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Markey, Ed (2008). "Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2008". 110th Congress (2007–2008) H.R.5353. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009, H.R. 3458

- ^ Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009, H.R. 3458

- ^ Markey, Ed (2009). "Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009". 111th Congress (2009–2010)H.R.3458. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ Anna Eshoo, Edward Markey (July 31, 2009). "Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009". United States Congress. Sec 3., Sec. 11 (of the Communications Act of 1934), (d) Reasonable Network Management

- ^ Kravets, David (December 20, 2012). "Net Neutrality, Data-Cap Legislation Lands in Senate". Wired. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ Lessig, L. 1999. Cyberspace’s Architectural Constitution, draft 1.1, Text of lecture given at www9, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- ^ a b c http://www.tiaonline.org/sites/default/files/pages/Internet_ecosystem_letter_FINAL_12.10.14.pdf

- ^ Tribune, Chicago. "The Internet isn't broken. Obama doesn't need to 'fix' it".

- ^ Schor, Elana (May 3, 2006). "Finance firms may weigh in on net-neutrality battle". The Hill. Archived from the original on June 12, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- ^ Crawford, Susan (April 28, 2014). "The Wire Next Time". New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ Broache, Anne (March 17, 2006). "Push for Net neutrality mandate grows". CNET News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- ^ http://cdn.moveon.org/content/pdfs/MoveOnChristianCoalition.pdf

- ^ Sacco, Al (June 9, 2006). "U.S. House Shoots Down Net Neutrality Provision". CIO.com. Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- ^ Tim Berners-Lee. "Net Neutrality: This is serious".

- ^ McMillan, Robert (May 16, 2014). "Websites Throttle FCC Staffers to Protest Gutting of Net Neutrality". Wired. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ "In Developing Countries, Google and Facebook Already Defy Net Neutrality – MIT Technology Review". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Entrepreneurs Explain How The End of Net Neutrality Would Mean Their Startups Don't Exist". Techdirt. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Net Neutrality and the Future of the Internet". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "MIT OpenCourseWare – Free Online Course Materials". mit.edu. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Chiaramonte, Perry (January 24, 2014). "Educators fear net neutrality reversal will increase cost of learning". Fox News.

- ^ [1] Archived January 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "What Is Net Neutrality?". The American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ Lawrence Lessig and Robert W. McChesney (June 8, 2006). "No Tolls on The Internet". Columns.

- ^ Morran, Chris (February 24, 2015). "These 2 Charts From Comcast Show Why Net Neutrality Is Vital". The Consumerist. Retrieved February 28, 2015.