Proper motion

Proper motion is the astronomical measure of the observed changes in apparent positions of stars in the sky as seen from the center of mass of the Solar System, as compared to the imaginary fixed background of the more distant stars.[1]

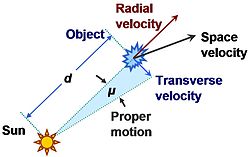

It was first physically measured individually in both seconds of time in right ascension (RA or α) and seconds of arc in declination (Dec. or δ), whose calculated combined value, is the total proper motion (μ)[2] expressed in seconds of arc per year (arcsec/yr) or per century (arcsec/100yr), where 3600 arcseconds equal one degree.[3] Because most proper motions are much less than one arcsec per year, most modern catalogues, like the Hipparcos Index Catalogue (HIP), now express proper motion in terms of milliarcseconds per year (mas/yr), where 1000 mas equals one arcsecond. This measured sky motion is separate from the radial velocity, measured in kilometres per second (km/s), being the velocity moving toward or away from the observer, as usefully obtained by the small Doppler shifts seen in starlight when using astronomical spectroscopy. Knowledge of the proper motion and Doppler shift allow approximate calculations of a star's true motion in space in respect to the Sun.

Proper motion is not entirely "proper" (that is, intrinsic to the star), because it includes a component due to the motion of the Solar System itself.[4]

Introduction

Over the course of centuries, stars appear to maintain nearly fixed positions with respect to each other, so that they form the same constellations over historical time. Ursa Major or Crux, for example, looks nearly the same now as they did hundreds of years ago. However, precise long-term observations show that the constellations change shape, albeit very slowly, and that each star has an independent motion.

This motion is caused by the movement of the stars relative to the Sun and Solar System. The Sun travels in a nearly circular orbit (the solar circle) about the center of the Milky Way at a speed of about 220 km/s at a radius of 8±0.65 kPc from the center,[5][6] which can be taken as the rate of rotation of the Milky Way itself at this radius.[7][8]

The proper motion is a two-dimensional vector (because it excludes the component in the direction of the line of sight) and is thus defined by two quantities: its position angle and its magnitude. The first quantity indicates the direction of the proper motion on the celestial sphere (with 0 degrees meaning the motion is due north, 90 degrees meaning the motion is due east, and so on), and the second quantity is the motion's magnitude, expressed in seconds of arc per year.

Proper motion may alternatively be defined by the angular changes per year in the star's right ascension (μα) and declination (μδ). On the celestial sphere, the coordinate of α corresponds to 'celestial' longitude, where all right ascensions are measured from the vernal equinox V, the point on the sky where the Sun crosses the celestial equator on near March 21. δ corresponds to 'celestial' latitude.[9]

The components of proper motion by convention are arrived at as follows. Suppose in a year an object moves from coordinates (α, δ) to coordinates (α1, δ1), with angles measured in seconds of arc. Then the changes of angle in seconds of arc per year are:[10]

The magnitude of the proper motion μ is given by vector addition of its components:[11][12]

,

where δ is the declination. The factor in cos δ accounts for the fact that the radius from the axis of the sphere to its surface varies as cos δ, becoming, for example, zero at the pole. Thus, the component of velocity parallel to the equator corresponding to a given angular change in α is smaller the further north the object's location. The change μα , which must be multiplied by cos δ to become a component of the proper motion, is sometimes called the "proper motion in right ascension", and μδ the "proper motion in declination".[13]

If the proper motion in right ascension has been converted by cos δ into either arcsecond or milliarcsecond, the result is expressed as μα* ('mu alpha asterisk'), i.e. the proper motion results in right ascension within the Hipparcos Catalogue (HIP) are expressed in the right ascension mas/yr, and therefore have already been converted.[14] Hence, the individual proper motions in right ascension and declination are made equivalent for straightforward calculations of various other stellar motions.

Position angle θ is related to these components by:[2][15]

Examples

For the majority of stars seen in the sky, the observed proper motions are usually small and unremarkable. Such stars are often either faint or are significantly distant, have changes of below 10 milliarcseconds per year, and do not appear to move appreciably over many millennia. A few do have significant motions, and are usually called high-proper motion stars. Motions can also be in almost seemingly random directions. Two or more stars, double stars or open star clusters, which are moving in similar directions, exhibit so-called shared or common proper motion (or cpm.), suggesting they may be gravitationally attached or share similar motion in space.

Barnard's star has the largest proper motion of all stars, moving at 10.3 seconds of arc per year. Large proper motion is usually a strong indication that a star is relatively close to the Sun. This is indeed the case for Barnard's Star, located at a distance of about 6 light-years. After the Sun and the Alpha Centauri system, it is the nearest known star to Earth. Because it is a red dwarf with an apparent magnitude of 9.54, it is too faint to see without a telescope or powerful binoculars.

A proper motion of 1 arcsec per year at a distance of 1 light-year corresponds to a relative transverse speed of 1.45 km/s. Barnard's star's transverse speed is 90 km/s and its radial velocity is 111 km/s (which is at right angles to the transverse velocity), which gives a true motion of 142 km/s. True or absolute motion is more difficult to measure than the proper motion, because the true transverse velocity involves the product of the proper motion times the distance. As shown by this formula, true velocity measurements depend on distance measurements, which are difficult in general. Currently, the nearby star with the largest true velocity (relative to the Sun) is Wolf 424, which moves at 555 km/s or 1/540 of the speed of light.

In 1992, Rho Aquilae became the first star to have its Bayer designation invalidated by moving to a neighbouring constellation – it is now a star of the constellation Delphinus.[16]

Usefulness in astronomy

Stars with large proper motions tend to be nearby; most stars are far enough away that their proper motions are very small, on the order of a few thousandths of an arcsecond per year. It is possible to construct nearly complete samples of high proper motion stars by comparing photographic sky survey images taken many years apart. The Palomar Sky Survey is one source of such images. In the past, searches for high proper motion objects were undertaken using blink comparators to examine the images by eye, but modern efforts use techniques such as image differencing to automatically search through digitized image data. Because the selection biases of the resulting high proper motion samples are well-understood and well-quantified, it is possible to use them to construct an unbiased census of the nearby stellar population — how many stars exist of each true brightness, for example. Studies of this kind show that the local population of stars consists largely of intrinsically faint, inconspicuous stars such as red dwarfs.

Measurement of the proper motions of a large sample of stars in a distant stellar system, like a globular cluster, can be used to compute the cluster's total mass via the Leonard-Merritt mass estimator. Coupled with measurements of the stars' radial velocities, proper motions can be used to compute the distance to the cluster.

Stellar proper motions have been used to infer the presence of a super-massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.[17] This black hole is suspected to be Sgr A*, with a mass of 4.2 × 106 M☉, where M☉ is the solar mass.

Proper motions of the galaxies in the Local Group are discussed in detail in Röser.[18] In 2005, the first measurement was made of the proper motion of the Triangulum Galaxy M33, the third largest and only ordinary spiral galaxy in the Local Group, located 0.860 ± 0.028 Mpc beyond the Milky Way.[19] Although the Andromeda Galaxy is known to move, and an Andromeda–Milky Way collision is predicted in about 5 – 10 billion years, the proper motion of the Andromeda galaxy, about 786 kpc distant, is still an uncertain matter, with an upper bound on its transverse velocity of ≈ 100 km/s.[8][20][21] Proper motion of the NGC 4258 (M106) galaxy in the M106 group of galaxies was used in 1999 to find an accurate distance to this object.[22] Measurements were made of the radial motion of objects in that galaxy moving directly toward and away from us, and assuming this same motion to apply to objects with only a proper motion, the observed proper motion predicts a distance to the galaxy of 7.2±0.5 Mpc.[23]

History

Proper motion was suspected by early astronomers (according to Macrobius, AD 400) but proof was provided in 1718 by Edmund Halley, who noticed that Sirius, Arcturus and Aldebaran were over half a degree away from the positions charted by the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus roughly 1850 years earlier.[24]

The term "proper motion" derives from the historical use of "proper" to mean "belonging to" (cf, propre in French and the common English word property). There is no such thing as "improper motion" in astronomy.[1]

Stars with high proper motion

The following are the stars with highest proper motion from the Hipparcos catalog.[25] See List of stars in the Hipparcos Catalogue. It does not include stars such as Teegarden's star, which are too faint for that catalog. A more complete list of stellar objects can be made by doing a criteria query at http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/ .

| # | Star | Proper motion | Radial velocity (km/s) |

Parallax (mas) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μα · cos δ (mas/yr) |

μδ (mas/yr) | ||||

| 1 | Barnard's star | −798.58 | 10328.12 | −110.51 | 548.31 |

| 2 | Kapteyn's star | 6505.08 | −5730.84 | +245.19 | 255.66 |

| 3 | Groombridge 1830 | 4003.98 | −5813.62 | −98.35 | 109.99 |

| 4 | Lacaille 9352 | 6768.20 | 1327.52 | +8.81 | 305.26 |

| 5 | Gliese 1 (CD −37 15492) (GJ 1) | 5634.68 | −2337.71 | +25.38 | 230.42 |

| 6 | HIP 67593 | 2118.73[27] | 5397.57[27] | -4.4 | 187.76 |

| 7 | 61 Cygni A & B | 4133.05 | 3201.78 | −65.74 | 286 |

| 8 | Lalande 21185 | −580.27 | −4765.85 | −84.69 | 392.64 |

| 9 | Epsilon Indi | 3960.93 | −2539.23 | −40.00 | 276.06 |

Software

There are a number of software products that allow a person to view the proper motion of stars over differing time scales. Two free ones are:

- HippLiner – Freeware – Windows, Moderately sophisticated, with some pretty displays. Still under development, needs some more navigation and configuration features.

- XEphem – Freeware – Linux and Apple OS X – complete astrometry package, can view a region of the sky, set a time step, and watch stars move over time.

- Proper Motion Simulator Web site - Runs in your browser. Watch the positions of the stars change with time. Fly through the constellations to get a sense of their volume.

See also

- Radial velocity

- Peculiar motion

- Solar apex

- Leonard-Merritt mass estimator

- Very Long Baseline Interferometry

- Galaxy rotation curve

- Celestial coordinates

- Milky Way

References

- ^ a b Theo Koupelis; Karl F. Kuhn (2007). In Quest of the Universe. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 369. ISBN 0-7637-4387-9.

- ^ a b D. Scott Birney; Guillermo Gonzalez; David Oesper (2007). Observational Astronomy. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-85370-5.

- ^ Simon F. Green; Mark H. Jones (2004). An Introduction to the Sun and Stars. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-521-54622-2.

- ^ D. Scott Birney; Guillermo Gonzalez; David Oesper (2007). Observational Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-521-85370-2.

- ^ Horace A. Smith (2004). RR Lyrae Stars. Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-521-54817-9.

- ^ M Reid; A Brunthaler; Xu Ye; et al. (2008). "Mapping the Milky Way and the Local Group". In F. Combes; Keiichi Wada (eds.). Mapping the Galaxy and Nearby Galaxies. Springer. ISBN 0-387-72767-1.

- ^ Y Sofu; V Rubin (2001). "Rotation Curves of Spiral Galaxies". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 39: 137–174. arXiv:astro-ph/0010594. Bibcode:2001ARA&A..39..137S. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.39.1.137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Abraham Loeb; Mark J. Reid; Andreas Brunthaler; Heino Falcke (2005). "Constraints on the proper motion of the Andromeda galaxy based on the survival of its satellite M33" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 633 (2): 894–898. arXiv:astro-ph/0506609. Bibcode:2005ApJ...633..894L. doi:10.1086/491644.

- ^ D. Scott Birney; Guillermo Gonzalez; David Oesper (2006). Observational Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-85370-2.

- ^ William Marshall Smart; Robin Michael Green (1977). Textbook on Spherical Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-521-29180-1.

- ^ Charles Leander Doolittle (1890). A Treatise on Practical Astronomy, as Applied to Geodesy and Navigation. Wiley. p. 583.

- ^ Majewski, Steven R. (2006). "Stellar Motions". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ Simon Newcomb (1904). The Stars: A study of the Universe. Putnam. pp. 287–288.

- ^ Matra Marconi Space, Alenia Spazio (September 15, 2003). "The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues : Astrometric and Photometric Star Catalogues derived from the ESA Hipparcos Space Astrometry Mission" (PDF). ESA. p. 25. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- ^ See Majewski, Steven R. (2006). "Stellar motions: parallax, proper motion, radial velocity and space velocity". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- ^ Hirshfeld, Alan; Sinnott, Roger W.; Ochsenbein, François; Lemay, D. (1992). "Book-Review – Sky Catalogue 2000.0 – V.1 – Stars to Magnitude 8.0 ED.2". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 86: 221. Bibcode:1992JRASC..86..221H.

- ^ AM Ghez; et al. (2003). "The First Measurement of Spectral Lines in a Short-Period Star Bound to the Galaxy's Central Black Hole: A Paradox of Youth". Astrophysical Journal. 586 (2): L127–L131. arXiv:astro-ph/0302299. Bibcode:2003ApJ...586L.127G. doi:10.1086/374804.

- ^ Andreas Brunthaler (2005). "M33 – Distance and Motion". In Siegfried Röser (ed.). Reviews in Modern Astronomy: From Cosmological Structures to the Milky Way. Wiley. pp. 179–194. ISBN 3-527-40608-5.

- ^ A. Brunthaler; M.J. Reid; H. Falcke; L.J. Greenhill; C. Henkel (2005). "The Geometric Distance and Proper Motion of the Triangulum Galaxy (M33)". Science. 307 (5714): 1440–1443. arXiv:astro-ph/0503058. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1440B. doi:10.1126/science.1108342. PMID 15746420.

- ^ Roeland P. van der Marel (2008). "M31 Transverse Velocity and Local Group Mass from Satellite Kinematics". The Astrophysical Journal. 678: 187–199. arXiv:0709.3747. Bibcode:2008ApJ...678..187V. doi:10.1086/533430.

- ^ Manuel Metz; Pavel Kroupa; Helmut Jerjen (2007). "The spatial distribution of the Milky Way and Andromeda satellite galaxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 374 (3): 1125–1145. arXiv:astro-ph/0610933. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.374.1125M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11228.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Steven Weinberg (2008). Cosmology. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-19-852682-2.

- ^ J. R. Herrnstein; et al. (1999). "A geometric distance to the galaxy NGC4258 from orbital motions in a nuclear gas disk". Nature. 400 (6744): 539–541. arXiv:astro-ph/9907013. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..539H. doi:10.1038/22972.

- ^ Otto Neugebauer (1975). A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. Birkhäuser. p. 1084. ISBN 3-540-06995-X.

- ^ Staff (September 15, 2003). "The 150 Stars in the Hipparcos Catalogue with Largest Proper Motion". ESA. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ "SIMBAD". Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ a b Fabricius, C.; Makarov, V.V. (May 2000). "Hipparcos astrometry for 257 stars using Tycho-2 data". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement. 144: 45–51. Bibcode:2000A&AS..144...45F. doi:10.1051/aas:2000198. Retrieved 2016-04-13.