Queen of Elphame

Queen of Elphame[1] or "Elf-hame" (-hame stem only occurs in conjectural reconstructed orthography[2][3]), in the folklore belief of Lowland Scotland and Northern England, designates the elfin queen of Faerie, mentioned in Scottish witch trials. She is equivalent to the Queen of Fairy who rules Faërie or Fairyland. The Queen, according to testimony, has a husband named "Christsonday".

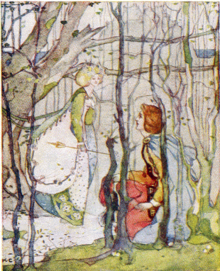

Such a queen also appears in the legend of Thomas the Rhymer, but she is queen of a nameless world in the medieval verse romance. The name "Queen of Elfland" is mentioned for her only in a later ballad (version A). Thomas the Rhymer's abduction by the queen was not just familiar folklore, but described as a kindred experience by at least one witch (Andro Man). The "Queen of Fairies" in Tam Lin may be the queen of the same world, at least, she too is compelled deliver humans as "tithe to hell" every seven years.[4]

In Scottish popular tradition the Fairy Queen was known as the Gyre-Carling or Nicnevin,[5] In one metrical legend, "The Faeries of Fawdon Hill" is where the Fairy Court is held, presided by Queen Mab.[6]

History of usage

The actual text spelling is "Quene of Elfame" and other variants in the witch trial transcripts, and the supposition of a -hame stem, leading to the etymological meaning "Elf-home" in the Scots language), is speculative on the part of Robert Pitcairn, the modern editor.[2][3][a] The Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue lists only the Elfame and elphyne spellings, both defined as "Fairyland".[7] Other spellings include: "Quene of Elphane" and "Court of Elfane" (accused witch Alison Pearson[2]), "Court of Elfame" (Bessie Dunlop),[3] "Queen of Elphen" (Andro Man).[8]

The "Queen of Elphame" designation was only used in isolated instances in the 19th century.[10] Serious scholarship on Thomas the Rhymer, for instance, generally do not employ this spelling. But it was embraced by Robert Graves who used "Queen of Elphame" in his works. Usage has since spread in various popular publications.

The theory that the queen whom Thomas Rhymer met at Erceldoune was the Saxon goddess Ercel, i.e. Hörsel or Ursel (cf. St. Ursula) according to a German origin explanation noted in passing by Fiske[11][b] though it has received scarce notice aside from Barbara G. Walker, who cites Graves's The White Goddess for this insight.[13][verification needed]

Descriptions of the queen

The Queen of Elphame was invoked, under various names, in Scottish witch trials. The forms "Queen of Elfame" (sic.) ("Elphane", also "Court of Elfane") occur in documents from the trial of Alison Pearson (Alesoun Peirsoun) in 1588,[14][15] and emendation to "elf-hame" was suggested by the editor, Robert Pitcairn. Alison was carried off to Elfame on a number of occasions over the years, where she made good acquaintance with the Queen. But rather than the Queen herself, it was mostly with her elfin minions that Alice engaged in specific interactions, with William Simpson, Alison's cousin or uncle being a particularly close-knitted mentor, teaching her medicinal herbs and the art of healing, which she then profited from by peddling her remedies to her patients, which included the Bishop of St. Andrews. The elfin folk from this world would arrive unexpectedly, allowing her to join in their herb-picking before sunrise, and brewing their salves (sawis) before her eyes. But they were often abusive, striking her in a manner that left her bereft of all her powers ("poistee" or "poustie") on her sides, rendering her bedridden for twenty weeks at a time.

The form "Queen of Elphen" occurs in the 1598 witchcraft trial indictment (ditty) and confession of Andro Man (Andrew Man) of Aberdeen.[16] Andro Man confessed that as a boy he saw "the Devil" his master "in the likeness and shape of a woman, whom [he] callest the Queen of Elphen," and as an adult, during the span of some thirty-two years he had carnal relations with the "Quene of Elphen" on whom he begat many bairns.[17] Further down however, the Devil whom he calls "Christsonday" is the goodman (husband), though "the Quene has grip of all the craft".[18]

Andro Man further confessed that on the Holy Rood Day (Ruidday in harvest) the Queen of Elphen and her company rode white horses (quhyt haiknayes) alongside the Devil (Christsondy) who appeared out of snow in the form of a stag. She and her companions had human shapes, "yet were as shadows", and that they were "playing and dancing whenever they pleased."[18][19]

Bessie Dunlop in 1576 confessed that the dead man's spirit she had congress with (Thom Reid) was one of "the good neighbours or brownies, who dwelt at the Court of Faery (Elf-hame)" ("gude wychtis that wynnitin the Court of Elfame.."), and they had come to take her away, but she refused to comply thereby angering Thom. When interrogated, Bessie denied having carnal relations with Thom, though he once took her by the apron and "wald haif had hir gangand with him to Elfame." Bessie was informed that the queen had secretly visited her before, and according to Thom, when Bessie lay in bed in child-birth, it was the "Quene of Elfame" who in the guise of a stout woman had offered her a drink and prophesied her child's death and her husband's cure. And indeed, it was at the behest of this Queen who was his master that Thom had come to Bessie at all.[20][21]

The Queen's shape-shifting magic extends to her own person. Andro Man's confession also noted that "she can be old or young as she pleases".[22][verification needed]

Marion Grant, of the same coven as Andro Man, witnessed the queen as a "fine woman, clad in a white walicot."[23] Similarly, Isobel Gowdie's confession described the "Qwein of Fearrie" as handsomely ("brawlie") clothed in white linen and in white and brown clothes, and that providing more food than Isobel could eat.[24][25]

Queen of Elfland in ballads

The traditional ballads do not call her the "Queen of Elphame" as such (except as so altered in Robert Graves's edition[26][27]). In ballad version A of Thomas the Rhymer names as "Queen of Elfland" the being who spirits Thomas away, and the two queens may be equivalent according to common belief. For instance, Andro Man's accusers charged that he had learned to his art of healing from his "Quene of Elphen" and plied his trade in return for "meit or deit", just like Thomas the Rhymer.[17][28] They also extracted from him the affirmation that he has known dead men like Thomas the Rhymer and the king who died in Flowdoun (James IV) who were in the Queen's company.[18]

Furthermore, the romance version of the Legend of Thomas the Rhymer speaks of the "fee to hell," synonymous with the "teindings unto hell" in the Greenwood (or "E") variant ballad (also occurs as "teind to hell" in the "Tam Lin"), while the aforementioned accused witch, "the poor Alison Pearson who lost her life in 1586 for believing these things, testified that the tribute was annual"[29][30]

In both the ballad and romance forms of the legend of Thomas the Rhymer, the supernatural queen initially mistaken for the Queen of Heaven (i.e., Virgin Mary) by the protagonist, but she identifies herself as "Queen of Elfland" (ballad A) or the queen of some supernatural realm that remains nameless (romance). The nameless land or romance is the same as the Elfland of ballad insofar as the queen is able to show Thomas three paths, one leading to her homeland and the other two to Heaven and Hell, and J. A. H. Murray says it is a place which would be called "Faërie or Fairy-land" in tales from later periods.[31]

True Thomas lay oer yond grassy bank,

And he beheld a ladie gay,

A ladie that was brisk and bold,

Come riding oer the fernie brae.

...

True Thomas he took off his hat,

And bowed him low down till his knee:

“All hail, thou mighty Queen of Heaven!

For your peer on earth I never did see.”

“O no, O no, True Thomas,” she says,

“That name does not belong to me;

I am but the queen of fair Elfland,

And I’m come here for to visit thee.

—"Thomas Rymer", Child's Ballad #37A[32]Thomas lay on Huntlie bank,

A-spying ferlies with his ee,

And he did espy a lady bold

Come riding down from the eldern tree

...

Thomas took off both cloak and cap,

And bowed him low down till his knee,

'O save you, save you, Queen of Heaven,

For your peer on earth I ne'er did see!'

'I'm not the Queen of Heaven, Thomas,

That name does not belong to me;

I am but the Queen of fair Elphame

Come out to hunt in my follie.

—Robert Grave's version, "Thomas the Rymer"[26]

But, in Tam Lin the equivalent character "Queen o' Fairies" is a more sinister figure. She captures mortal men, and entertains them in her subterranean home; but then uses them to pay a "teind to Hell":

'And ance it fell upon a day,

A cauld day and a snell,

When we were frae the hunting come,

That frae my horse I fell,

The Queen o' Fairies she caught me,

In yon green hill do dwell.

"And pleasant is the fairy land,

But, an eerie tale to tell,

Ay at the end of seven years,

We pay a tiend to hell,

I am sae fair and fu o flesh,

I'm feard it be myself.

—;"Tam Lin", Child's Ballad #39A, str.23-24

[33]

Sempill ballad

Robert Sempill in a ballad (1583) on the bishop Patrick Adamson refers to Alison Pearson participating in the fairy ride.[34][35] The Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue also, in giving the entry Elphyne "Fairy-land," and gives Sempill's ballad as an example in usage.[36][37]

For oght the kirk culd him fobid, He sped him sone, and gat the thrid; Ane carling of the Quene of Phareis, That ewill win geir to elphyne careis; Through all Braid Abane scho hes bene, On horsbak on Hallow ewin; And ay in seiking cetayne nyghtis, As scho sayis with sur [our] sillie wychtis. — R.S., 'Legend of the Bischop of St. Androis Lyfe, callit Mr Patrick Adamsone alias Cousteane", Poems 16th Cent. in: Scottish Poems of the XVIth Century, p. 320-321[38][40]

Robert Jamieson also noted the ballad under the etymological explanation of seelie meaning "happy."[39] The ballad thus mention the Queen of Fairies, elphyne meaning Elfland (Fairyland), and seelie witches in a single passage.

See also

- Álfheimr - Homeland of elves in Norse mythology

- Border ballads

- Elf

- Fairy Queen

- Fairy

- Otherworld

- Classifications of fairies

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ^ Note that Pitcairn he appends a question mark in one footnote (I, 162) but none in the other (I, 53).

- ^ Fiske explained Erceldoune was ("Hörsel-Hill"), alluding to the Hörsel or Ursel, a goddess who Baring-Gould proposed was the archetype of St. Ursula.[12]

Citations

- ^ a b Pitcairn 1833

- ^ a b c In the trial of "Alesoun Peirsoun in Byrehill" of 1588, original transcripts read "Quene of Elfame," "Quene of Elphane," and "Court of Elfane", which Pitcairn's glosses in footnote as: "The brownies or fairies, and the Queen of Faery (q. d. elf-hame ?) (Pitcairn 1833, Vol. 1, Part 3, p.162)

- ^ a b c In the trial of Bessie or Elisabeth Dunlop, "Elfame" in text glossed: "the good neighbours or brownies, who dwelt at the Court of Faery (Elf-hame) (Pitcairn 1833, Vol. 1, Part 2, p.53)

- ^ Child, Francis James (1884), "39. Tam Lin", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. 1 (Part 2), Houghton Mifflin, pp. 335–357

- ^ "Introduction to the Tale of Tamerlane: On the Fairies of Popular Superstition", Part IV, p.198 in: Scott, Walter (1803). Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. Vol. 2. James Ballantyne. pp. 174–241.:

- ^ Metrical Legends of Northumberland: containing the traditions of Dunstanborough Castle, and other poetical romances. With notes and illustrations, James Service, W. Davison, 1834

- ^ a b DOST (Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue) entry, retrieved using the electronic "Dictionary of the Scots Language". Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Miscellany of the Spalding Club (1841), 1, pp.119-125

- ^ Chambers's Edinburgh Journal (1844-04-27), Vol. 1, No. 1, p.259

- ^ In Pitcairn's index,[1] cross-referencing to I, 52, 56 (Bessie Dunlop case) and I, 162 (Alison Pearson); and later in regards to Andro Man by Chambers's Journal[9]

- ^ Fiske, John (1885) [1873]. Myths and Myth-maker (7 ed.). Houghton, Mifflin and Company. p. 30.

- ^ Baring-Gould, Sabine (1868). Curious Myths of the Middle Ages. Vol. 2. Rivingtons. p. 66.

- ^ Walker, Barbara (1983). The Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets. Harper&Row., under heading "Thomas Rhymer." She cites Graves, W. G., p. 483 in the paragraph, though Graves does not seem to have made this Ersel/Hörsel/Ursel goddess connection in this work.

- ^ Pitcairn 1833, Vol. 1, Part 2, p.161-5

- ^ Rendered into modern prose, in:Linton, Elizabeth Lynn (1861). Witch Stories. Chapman and Hall. pp. 12–.

- ^ The Miscellany of the Spalding Club, vol. 1, 1841, pp. 119–125

- ^ a b Miscellany of the Spalding Club, 1, p.119

- ^ a b c Miscellany of the Spalding Club, 1, p.121

- ^ "Did Shakespeare Visit Scotland", in Chambers' Edinburgh Journal, Apr. 27, 1844

- ^ Pitcairn 1833, Vol. 1, Part 2, pp.49-, 53, 56, 57

- ^ Linton 1861, Witch Stories, pp.8-12

- ^ Robert Graves, English and Scottish Ballads (Heinemann, 1963), p. 157.

- ^ Miscellany of the Spalding Club, 1, p.171

- ^ Pitcairn 1833, Vol. 3, p.604

- ^ Thomas Wright, Narratives of sorcery and magic, from the most authentic sources (Redfield, 1852), pp. 350, 352

- ^ a b Graves, Robert. English and Scottish ballads.

- ^ Hoffman, Daniel G. (1959). "The Unquiet Graves". The Sewanee Review. 67 (2): 305–316. JSTOR 27538819., written like an ode, questions if "he actually found either a folk informant or a re liable printed text for his unique"

- ^ Noted in Murray 1875, p. xlvi

- ^ Commonality between the Rhymer's romance and "Tam Lin" noted in Child 1884, Vol. I, p.339 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFChild1884 (help)

- ^ Greenwood variant given in Child 1892, Pop. Ball. IV, pp.454-5; referred to as "E" version by later scholars such as Emily B. Lyle.

- ^ Murray, James A. H., ed. (1875). The Romance and Prophecies of Thomas of Erceldoune: printed from five manuscripts; with illustrations from the prophetic literature of the 15th and 16th centuries. EETS O.S. Vol. 61. London: Trübner. p. xxiii.

- ^ Child, Francis James (1884), "37. Thomas Rymer", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. 1 (Part 2), Houghton Mifflin, pp. 317–329

- ^ Child, Francis James (1884), The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. 1 (Part 2), Houghton Mifflin, pp. 335–338 https://books.google.com/books?id=m9IVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA335

{{citation}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Pitcairn 1833, Vol. 1, Part 3, p.163n

- ^ Henderson, Lizanne; Cowan, Edward J. (2001). Scottish Fairy Belief: A History. Dundrun. p. 166. ISBN 9781862321908.

- ^ The DOST (Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue) cites year 1583 for "Sempill Sat. P. xlv. 372", i.e., Robert Sempill (1891). Cranstoun, James (ed.). Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation. Vol. 1. William Blackwell and Sons for the Scottish Text Society. p. 365. (Poem 45, v.372).[7]

- ^ Cranstoun ed., Volume 2 (1893), p. 320 contains a glossary which defines elphyne as "elfland".

- ^ The fuller title taken from: Dalyell, John Graham Dalyell, Sir, 6th Bart. (1801), Scotish Poems of the Sixteenth Century, Edinburgh: Printed for Archibald Constable https://books.google.com/books?id=V3pLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA320

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jamieson, John (1825), Supplement to the Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language, Printed at the University Press for W. & C. Tait https://books.google.com/books?id=amAJAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA362

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Text given is as quoted by Jamieson[39]

References

- Chambers, William; Chambers, Robert (27 April 1844), Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, vol. 1, p. 259

- Pitcairn, Robert, ed. (1833). Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland. Vol. Vol. 1, Part 2. Edinburgh: Printed for the Bannatyne Club. pp. 49–, 53, 56, 57.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) (Bessie Dunlop)- Vol. 1, Part 3, pp. 162–165 (Alison Pearson)

- Vol. 3, Part 2, pp. 604-, p. 658 (Appendix:Isobel Gowdie, index)

- The Miscellany of the Spalding Club, vol. 1, 1841, pp. 119–125