Second Thomas Shoal

| Disputed atoll | |

|---|---|

Second Thomas Shoal | |

| Other names | Ayungin Shoal (Philippine English) Bãi Cỏ Mây (Vietnamese) Buhanginan ng Ayungin (Filipino) Rén'ài Jiāo 仁爱礁/仁愛礁 (Chinese) |

| Geography | |

| Location | South China Sea |

| Coordinates | 9°44′N 115°52′E / 9.733°N 115.867°E |

| Archipelago | Spratly Islands |

| Administration | |

| Region | Southwestern Tagalog Region |

| Province | Palawan |

| Municipality | Kalayaan |

| Claimed by | |

Second Thomas Shoal, also known as Ayungin Shoal (Filipino: Buhanginan ng Ayungin, lit. 'sandbank of silver perch'), Bãi Cỏ Mây (Vietnamese) and Rén'ài Jiāo (Chinese: 仁爱礁/仁愛礁),[1] is a submerged reef in the Spratly Islands of the South China Sea, 105 nautical miles (194 km; 121 mi) west of Palawan, Philippines.[2] It is a disputed territory and claimed by multiple nations.[3]

The reef is occupied by a garrison of Philippine Navy personnel aboard a ship, the BRP Sierra Madre, that was intentionally grounded on the reef in 1999 and has been periodically replenished since then.

History

[edit]The atoll is one of three named after Thomas Gilbert, captain of the Charlotte:

- First Thomas Shoal – 09°19′N 115°56′E / 9.317°N 115.933°E, South of Second Thomas Shoal.[4]

- Second Thomas Shoal – 09°44′N 115°52′E / 9.733°N 115.867°E, Southeast of Mischief Reef.[4]

- Third Thomas Shoal – 10°54′N 115°56′E / 10.900°N 115.933°E, Northeast of Flat Island – some distance North of Second Thomas Shoal.[5]

Geographical location

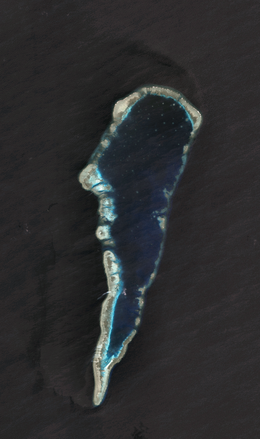

[edit]Located south-east of Mischief Reef (09°55′N 115°32′E / 9.917°N 115.533°E), Second Thomas Shoal is near the centre of Dangerous Ground in the north-eastern part of the Spratly Islands. There are no settlements north or east of it.[4][5] It is a tear-drop shaped atoll, 11 nautical miles (20 km; 13 mi) long, from north to south[6] and fringed with coral reefs.[7] The coral rim surrounds a lagoon, which has depths of up to 27 metres (89 ft) and is accessible to small boats from the east. Drying reef patches are found east and west of the reef rim.

Geographical features

[edit]On July 12, 2016, the UNCLOS tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration concluded that Second Thomas Shoal is, or in its natural condition was, exposed at low tide and submerged at high tide and, accordingly, has low-tide elevations that do not generate an entitlement to a territorial sea, exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.[8]

Territorial claims

[edit]Second Thomas Shoal is claimed by China, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.[9]

The Philippine Navy maintains a presence of less than a dozen Marine personnel on a 100 m (330 ft) long Second World War US-built Philippine Navy landing craft, the BRP Sierra Madre, which was deliberately run aground at the atoll in 1999, in response to the Chinese reclamation of Mischief Reef.[10][11] The Philippines claims that the atoll is part of its continental shelf.[12] Parts of the Spratly group of islands, where Second Thomas Shoal lies, are claimed by China, Brunei, the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam.

Standoffs

[edit]In response to China's occupation of Mischief Reef in 1994, Philippine president Joseph Estrada in 1998 decided to "as well put up our own structures". In May 1999, two Philippine ships—the BRP Sierra Madre and the BRP Lanao del Norte—were intentionally grounded on the shoal. According to Chinese officials' narrative, the Philippines partly complied with China's demand to remove the ships, towing away the BRP Lanao del Norte but leaving the BRP Sierra Madre on the shoal.[13] Estrada promised that the latter vessel would also be towed away.[14][15] However, the BRP Sierra Madre served as an informal outpost of the Philippine Navy until 2014, when the Philippines declared it a "permanent installation";[13] in response, the Chinese government asked the Philippines to remove the grounded ship.[16][17]

Philippine supply ships have avoided Chinese blockades in order to deliver food, water and other supplies to the BRP Sierra Madre garrison.[18] PRC coast guard vessels blocked two attempts by Philippine ships to resupply the garrison on March 9, 2014, thus supplies were airdropped to it three days later. Another supply ship with replacement troops successfully reached the atoll on March 29, 2014, by sailing through shallow waters where the PRC vessels, having deeper drafts, were unable to follow.[19] Since then, the Philippine military has been sending relief and provisions by supply boats.[20]

In 2017, the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte accepted a gentlemen's agreement with China to maintain the status quo for the South China Sea while both sides tried to strengthen their relations.[21][22] Under the status quo agreement, no construction materials would be allowed to fortify the Sierra Madre to avoid escalations.[23] In 2023, Philippine president Bongbong Marcos said, "I am not aware of such agreement. If there was, I rescind it as of this moment".[24][25] A year later, Marcos said he was "horrified" by revelations about the said "gentlemen's agreement".[26]

In November 2021 and August 2023, China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels used water cannons and blocked Philippine supply boats, preventing the boats from delivering essential supplies to the Philippine marines stationed on the Sierra Madre.[27][28] On October 22, 2023, Philippine officials disclosed that Chinese vessels had rammed a Philippine Coast Guard ship and a military-run supply boat on October 17, during a replenishment mission to the Sierra Madre.[29] Earlier in the same year, a PRC coast guard ship intercepted a Philippine coast guard ship en route to the Sierra Madre and beamed a green laser light at the latter, which light the Philippine side alleged was "military grade" and caused its crew to suffer from temporary blindness. The incident, which China denied, led to the Philippines' filing of a diplomatic protest.

In April 2024, China stated it reached an agreement with the Philippines in adopting a "new model" over the disputed atoll; the claim, however, was refuted by Philippine defense secretary Gilberto Teodoro, who said that the Philippines would not enter into any agreements compromising its territorial claims.[30] In June, China's coast guard interfered with a new supply mission to the Sierra Madre by the Philippine Navy. A month later, a "provisional agreement" on supply missions had been reached between China and the Philippines as part of efforts to de-escalate tensions, with the details kept secret.[31] On August 20, the day after a clash between the two coast guards occurred near the Sabina Shoal, the Philippine government stated it was considering expanding the provisional agreement covering the Second Thomas Shoal to other areas.[32]

Alternate names

[edit]The Singapore National University Gazetteer,[33] and the US NGA Gazetteer[34] list the following as other names for the Second Thomas Shoal:

- Filipino – Ayungin

- French – Banc Thomas Deuxième

- Mandarin Chinese – Ren'ai Jiao

- Other Chinese names – Jen-ai An-sha, Jen-ai Chiao, Jên-ai Chiao, Ren'ai Ansha, 仁愛暗沙, 仁爱礁, 断节

- Other English names – Thomas Shoal Second

- Other names – Duanjie

- Vietnamese – Bãi Cỏ Mây

References

[edit]- ^ Sailing Directions – South China Sea. Taunton: UK Hydrographic Office.

- ^ Sailing Directions Enroute : Publication 158 – Philippine Islands. Springfield, Virginia: US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). 2013.

- ^ "TOPIC: Sierra Madre, Second Thomas Shoal, and the U.S. Commitment to Defense of the Philippines" (PDF). pacom.mil. February 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c NGA Chart 93046 – SE Dangerous Ground

- ^ a b NGA Chart 93045 – NE Dangerous Ground

- ^ Sailing Directions (Enroute), Pub. 161: South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand (PDF). Sailing Directions. United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 2017. p. 15.

- ^ "Imagery – Landsat 7 Path 118 Row 53". NASA. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "Award" (PDF). Permanent Court of Arbitration. July 12, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 29, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2016. p.174

- ^ Robert C. Beckman; Ian Townsend-Gault; Clive Schofield; Tara Davenport; Leonardo Bernard (January 2013). Beyond Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea: Legal Frameworks. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-78195-594-9.

- ^ "A game of shark and minnow". The New York Times. October 27, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Michael. "Manila monitoring Chinese shoal moves". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "DFA statement on China's allegation that the PH agreed to pull out of Ayungin Shoal". Department of Foreign Affairs (Philippines). Official Gazette (Philippines). March 14, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Green, Michael; Hicks, Kathleen; Cooper, Zack; Schaus, John; Douglas, Jake (May 24, 2017). Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia: The Theory and Practice of Gray Zone Deterrence. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 170-171. ISBN 978-1-4422-7998-8. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ "Letter | Philippine-China 'gentleman's agreement' on South China Sea is best adhered to". South China Morning Post. April 26, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ https://www.manilatimes.net/2023/08/14/opinion/columns/ph-did-promise-to-remove-brp-sierra-madre-from-ayungin/1905253 PRESIDENT Joseph Estrada did promise in 1999 to remove the BRP Sierra Madre, which his Navy deliberately grounded on Ayungin (Second Thomas Shoal). In the instances when the governments of Estrada and later of President Benigno Aquino 3rd were reminded of that commitment by the Chinese, they claimed that technical difficulties prevented them from removing the landing ship, tank (LST) Sierra Madre.

- ^ "China 'posturing' to seize Ayungin – Golez". Rappler. March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Esmaquel, Paterno (March 18, 2014). "China digs up details vs PH on Ayungin". Rappler. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ de Castro, Erik; Ng, Roli (March 31, 2014). "Philippine ship dodges China blockade to reach South China Sea outpost". www.reuters.com. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Gomez, Jim, Associated Press, "Philippine supply ship evades Chinese blockade", March 29, 2014

- ^ Campbell, Eric (May 20, 2014). "Reef Madness". ABC News. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Letter | Philippine-China 'gentleman's agreement' on South China Sea is best adhered to". South China Morning Post. April 26, 2024. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1AV0VS/ China has assured the Philippines it will not occupy new features or territory in the South China Sea, under a new "status quo" brokered by Manila as both sides try to strengthen their relations, the Philippine defence minister said.

- ^ Bautista, Jane. "Duterte's China 'agreement' on Ayungin prevented supply of construction material, says his spokesman". Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ Corrales, Nestor (August 10, 2023). "Pact on Ayungin rescinded, if there's any – Marcos". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ https://pco.gov.ph/news_releases/no-existing-agreement-to-remove-brp-sierra-madre-from-ayungin-shoal-pbbm/ “And let me go further, if there does exist such an agreement, I rescind that agreement now,” President Marcos said. PND

- ^ "Marcos 'horrified' by Xi-Duterte 'gentleman's agreement' on South China Sea". South China Morning Post. April 10, 2024. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ "Chinese vessels use water cannon to block Philippines vessels from disputed shoal". TheGuardian.com. November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Philippines tells China it will not abandon post in disputed reef". CNA. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Philippines says a coast guard ship and supply boat were rammed by Chinese vessels at disputed shoal". AP News. October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Philippines denies deal with China over disputed South China Sea shoal". April 26, 2024.

- ^ Edjen Oliquino (August 13, 2024). "Phl-China pact over Ayungin Shoal subject to review, says DFA". Daily Tribune. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Darryl John Esguerra (August 20, 2024). "PH mulls expanding Ayungin Shoal 'provisional arrangement' with China". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Spratly Islands – Names" (PDF). Gazetteer 75967. National University, Singapore. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ "Spratly Islands Gazetteer". US NGA.