Sonora

Sonora | |

|---|---|

| Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora | |

|

| |

State of Sonora within Mexico | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Capital | Hermosillo |

| Largest City | Hermosillo |

| Municipalities | 72 |

| Admission | January 10, 1824[1] |

| Order | 12th[a] |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Claudia Pavlovich |

| • Senators[2] | Anabel Acosta Islas Ernesto Gandara Camou Alfonso Burquez Valenzuela |

| • Deputies[3] | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 179,355 km2 (69,249 sq mi) |

| Ranked 2nd | |

| Highest elevation | 2,620 m (8,600 ft) |

| Population (2015)[6] | |

| • Total | 2,850,330 |

| • Rank | 18th |

| • Density | 16/km2 (41/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 27th |

| Demonym | Sonorense |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST [7]) |

| Postal code | 83–85 |

| Area code | |

| ISO 3166 code | MX-SON |

| HDI | |

| GDP | US$ 16,416,142.57 th[b] |

| Website | Official Web Site |

| ^ a. Joined to the federation under the name of Estado de Occidente (Western State) also recognized as Sonora y Sinaloa. ^ b. The state's GDP was $210,126,625 thousand of pesos in 2008,[8] amount corresponding to $16,416,142.57 thousand of dollars, being a dollar worth 12.80 pesos (value of June 3, 2010).[9] | |

Sonora (Spanish pronunciation: [soˈnoɾa] ), officially Free and Sovereign State of Sonora (Template:Lang-es), is one of 31 states that, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 72 municipalities; the capital city is Hermosillo. Sonora is located in Northwest Mexico, bordered by the states of Chihuahua to the east, Baja California to the northwest and Sinaloa to the south. To the north, it shares the U.S.–Mexico border with the states of Arizona and New Mexico, and on the west has a significant share of the coastline of the Gulf of California.

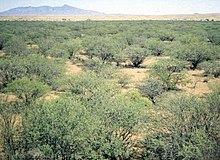

Sonora's natural geography is divided into three parts: the Sierra Madre Occidental in the east of the state; plains and rolling hills in the center; and the coast on the Gulf of California. It is primarily arid or semiarid deserts and grasslands, with only the highest elevations having sufficient rainfall to support other types of vegetation.

Sonora is home to eight indigenous peoples, including the Mayo, the Yaqui, and Seri. It has been economically important for its agriculture, livestock (especially beef), and mining since the colonial period, and for its status as a border state since the Mexican–American War. With the Gadsden Purchase, Sonora lost more than a quarter of its territory.[10] From the 20th century to the present, industry, tourism, and agribusiness have dominated the economy, attracting migration from other parts of Mexico.

Etymology

Several theories exist as to the origin of the name "Sonora". One theory states that the name was derived from Nuestra Señora, the name given to the territory when Diego de Guzmán crossed the Yaqui River on the day of Nuestra Señora del Rosario ("Our Lady of the Rosary"), which falls on 7 October with the pronunciation possibly changing because none of the indigenous languages of the area have the ñ sound. Another theory states that Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his companions, who had wrecked off the Florida coast and made their way across the continent, were forced to cross the arid state from north to south, carrying an image of Nuestra Señora de las Angustias ("Our Lady of Anguish") on a cloth. They encountered the Opata, who could not pronounce Señora, instead saying Senora or Sonora. A third theory, written by Father Cristóbal de Cañas in 1730, states that the name comes from the word for a natural water well, sonot, which the Spaniards eventually modified to "Sonora". The first record of the name Sonora comes from explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, who passed through the state in 1540 and called part of the area the Valle de la Sonora. Francisco de Ibarra also traveled through the area in 1567 and referred to the Valles de Señora.[11]

History

Pre-Hispanic period

Evidence of human existence in the state dates back over 10,000 years, with some of the best-known remains at the San Dieguito Complex in the El Pinacate Desert. The first humans were nomadic hunter gatherers who used tools made from stones, seashells, and wood.[12][13] During much of the prehistoric period, the environmental conditions were less severe than they are today, with similar but more dense vegetation spread over a wider area.[14]

The oldest Clovis culture site in North America is believed to be El Fin del Mundo in northwestern Sonora. It was discovered during a 2007 survey. It features occupation dating around 13,390 calibrated years BP.[15] In 2011, remains of Gomphothere were found; the evidence suggests that humans did in fact kill two of them here.

Agriculture first appeared around 400 BCE and 200 CE in the river valleys. Remains of ceramics have been found dating from 750 CE with diversification from 800 and 1300 CE[13] Between 1100 and 1350, the region had socially complex small villages with well-developed trade networks. The lowland central coast, however, seems never truly to have adopted agriculture.[14] Because Sonora and much of the northwest does not share many of the cultural traits of that area, it is not considered part of Mesoamerica. Though evidence exists of trade between the peoples of Sonora and Mesoamerica, Guasave in Sinaloa is the most north-westerly point considered Mesoamerican.[16]

Three archaeological cultures developed in the low, flat areas of the state near the coast: the Trincheras tradition, the Huatabampo tradition, and the Central Coast tradition. The Trincheras tradition is dated to between 750 and 1450 CE and mostly known from sites in the Altar, Magdalena, and Concepción valleys, but its range extended from the Gulf of California into northern Sonora. The tradition is named after trenches found in a number of sites, the best known of which is the Cerro de Trincheras. The Huatabampo tradition is centered south of the Trincheras along the coast, with sites along extinct lagoons, estuaries, and river valleys. This tradition has a distinctive ceramic complex. Huatabampo culture shows similarities with the Chametla to the south and the Hohokam to the north. This probably ended around 1000 CE. Unlike the other two tradition, the Central Coast remained a hunter-gatherer culture, as the area lacks the resources for agriculture.[17]

The higher elevations of the state were dominated by the Casas Grandes and Río Sonora tradition. The Río Sonora culture is located in central Sonora from the border area to modern Sinaloa. A beginning date for this culture has not been determined but it probably disappeared by the early 14th century. The Casas Grandes tradition in Sonora was an extension of the Río Sonora tradition based in the modern state of Chihuahua, which exterted its influence down to parts of the Sonoran coast.[18][19]

Climatic changes in the middle of the 15th century resulted in the increased desertification of northwest Mexico in general. This is the probable cause for the drastic decrease in the number and size of settlements starting around this time. The peoples that remained in the area reverted to a less complex social organization and lifestyle.[20] Whatever socially complex organization existed in Sonora before the Spaniards were long gone by the 16th century.[19]

Colonial period

Little reliable information remains about the area in the 16th century following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Some state that the first Spanish settlement was founded by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in 1530, near Huépac. Others state that Francisco Vásquez de Coronado founded a village on the edge of the Yaqui River in 1540 on his way north.[18][20][21] Another source states that the first Spanish presence was not until 1614, by missionaries such as Pedro Méndez and Pérez de Rivas, working with the Mayo.[22] Unlike in central Mexico, no central social or economic centralization occurred in the Sonora area, given the collapse of population centers in the 15th century. The five traditions of the past had broken down to a number of fractured ethnicities. No empire or other system was present for the Spaniards to co-opt for domination purposes.[18][20] In addition, the Yaqui people resisted European intrusion on their lands, effectively keeping the Spaniards out of their area until the 17th century.[23] While exploration of the area happened through the expeditions of the 16th century, significant permanent Spanish settlement did not become possible until the establishment of the mission system.[18][20][24][25]

Jesuit priests began to work in Sonora in the 1610s in the lowlands near the coast. Originally, these missionaries worked out a peaceful compromise with the 30,000 Yaquis allowing for the establishment of more than fifty mission settlements in the Sonora river valleys. This broke down when the Jesuits opposed the native shamanic religious tradition. The Opata were more receptive to the missionaries and allied with them. After this, the Jesuits began to move into Pima and Tohono O'odham territories.[23] Spanish exploration and missionary work was sufficient to consider the territory part of New Spain. An agreement between General Pedro de Perea and the viceroy of New Spain resulted in the general shaping of the province, initially called Nueva Navarra in 1637, but renamed Sonora in 1648.[22]

The most famous missionary of Sonora, as well as much of what is now the American Southwest, was Eusebio Kino.[26] He arrived in Sonora in 1687 and started missionary work in the Pimería Alta area of Sonora and Arizona. He began his first mission at Cucurpe, then established churches and missions in other villages such as Los Remedios, Imuris, Magdalena, Cocóspera, San Ignacio, Tubutama and Caborca. To develop an economy for the natives, Father Kino also taught them European farming techniques.[21][27]

The initial attraction of Sonora for the Spaniards was its fertile farmlands along the river valleys[28] and its position as part of a corridor linking the central Mexican highlands around Mexico City up the Pacific coast and on into Arizona and points north. This corridor still exists in the form of Federal Highway 15.[29] After the establishment of the mission system, Spanish colonists followed. Indigenous response was a mixture of accommodation and violence, as different strategies were employed by different groups at different times. The sporadic violence, which would continue throughout the colonial period, resulted in the Spanish building presidios and other fortifications to protect missions and Spanish settlements.[21][23] While the colonization process was not especially violent, the impact on the indigenous of the area was severe, as it almost completely disrupted their formerly very independent lives, forcing them to conform to an alien centralized system. One consequence of this was alcoholism among the native peoples.[22]

In 1691, what are now the states of Sonora and Sinaloa were joined into an entity called the Provincias de Sonora, Ostimuri, y Sinaloa. They would remain as such through the rest of the colonial period until 1823.[27] At this time, about 1,300 Spanish settlers were in the area.[30] Colonization increased in the 18th century, especially from 1700 to 1767, when mineral deposits were discovered, especially in Álamos. This led to the establishment of a number of royally controlled mining camps, forcing many natives off their agricultural lands. Loss of said lands along the Yaqui and Mayo Rivers led to native uprisings during this time.[22] A major Seri rebellion took place on the coast area in 1725–1726, but the largest uprising was by the Yaquis and Mayos from 1740 to 1742 with the goal of expelling the Spaniards. Part of the reason for the rebellion was that the Jesuits, as well as the secular Spaniards, were exploiting the indigenous. This rebellion destroyed the reputation of the Jesuit mission system. Another Seri rebellion occurred in 1748, with Pima and Tohono O’otham support and lasted into the 1750s. This kept the settlement situation in disarray. With population of the Mexican split half indigenous and half Spanish, about one-quarter of the indigenous population lived in Sonora alone.[31] In 1767, the king of Spain expelled the Jesuits from Spanish-controlled territories, ending the mission system.[32]

Independence

In 1821, the colonial era in Sonora was ended by the Mexican War of Independence, which started in 1810. However, Sonora was not directly involved in the war, as independence came by way of decree. One positive aspect of independence is that it allowed for economic development. The former province of Sonora, Ostimuri, y Sinaloa was divided in 1823 to form the states of Sonora and Sinaloa, with the Sonoran capital in Ures.[27] However, they were reunited in 1824 and remained so until the 1830s, despite of the fact that Sonora was declared a state by the 1824 Constitution of Mexico.[26] Sonora became separate again in 1831, when it wrote its first state constitution, which put the capital in Hermosillo. In 1832, the capital was moved to Arizpe.[27]

In 1835, the government of Sonora put a bounty on the Apache which, over time, evolved into a payment by the government of 100 pesos for each scalp of a male 14 or more years old. James L. Haley wrote: "In 1835, Don Ignacio Zuniga, who was the long-time commander of the presidios of northern Sonora, asserted that since 1820 the Apaches had killed at least five thousand settlers, which convinced another four thousand to flee, forced the abandonment of over one hundred settlements, and caused the virtual depopulation of the interior frontier. ... The state of Sonora resorted to paying a bounty on Apache scalps in 1835."[33]

The struggles between the Conservatives, who wanted a centralized government, and Liberals, who wanted a federalist system, affected the entire country during the 19th century. In 1835, a centralist government was instituted based on what were called the Bases Constitutionales ("Constitutional Bases"). They were followed by the Siete Leyes Constitutionales ("Seven Constitutional Laws"), which remained in effect until 1837. But in December of the same year, General José de Urrea proclaimed in Arizpe the re-establishment of the Constitution of 1824, initially supported by then Governor Manuel Gándara. However, for the rest of the century, Gándara and succeeding governors would support a centralized government, leading to political instability in the state.[21][27] In 1838, the capital was moved back to Ures.[21]

The fertile lands of the Mayo and Yaquis continued to attract outsiders during the 19th century. These were now Mexicans rather than Spaniards, and later in the century, it was a major draw for North Americans.[28] By the end of the 19th century, however, the area received large numbers of immigrants from Europe, especially from Germany, Italy, and Russia, the Middle East, mainly Lebanon or Syria, and even China,[34] who brought new forms of agriculture, mining, livestock, industrial processes, ironwork, and textiles.[26]

The Mexican–American War resulted in only one major military confrontation between Mexican and U.S. forces, but its consequences were severe for the state. In October 1847, the warship USS Cyane laid siege to Guaymas Bay, resulting in U.S. control of this part of the coast until 1848.[27][35] When the war ended, Sonora lost 339,370 hectares of its territory to the U.S. through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Additionally, the war ruined the state's economy.[27] Sonora lost more territory in the 1850s, through the Gadsden Purchase. Before the war, Sonora was the largest entity in Mexico, but as a result of the Gadsden Purchase, the northernmost part of the state became part of the United States. The majority of the area is today's Arizona south of the Gila River and a part of the present-day southwestern New Mexico.[21] The area's political vulnerability immediately after the war made it susceptible to buccaneers such as William Walker, Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon, and Henry Alexander Crabb, who attacked Sonoran ports such as Guaymas and Caborca. However, most attacks were repelled.[21] The economy did not begin to recover from the war until the late 1850s, when Ignacio Pesqueira became governor and attracted foreign investment to the state, especially in the mining sector, as well as worked to create markets abroad for agricultural products.[27]

During the French intervention in Mexico, Sonora was invaded by French troops as part of the effort to install Maximilian I as a monarch in Mexico. The port of Guaymas was attacked by forces under Armando Castagny, forcing Mexican forces under Pesqueira and General Patoni to retreat north of the city. French troops attacked the Mexicans again at a place called La Pasión, again resulting in defeat for the Mexican resistance. The French were not defeated in the state until the Battle of Llanos de Ures in 1866 by Pesqueria, Jesús García Morales and Ángel Martínez.[26][36] Shortly after this, the state's current constitution was written in 1871, and its capital was permanently moved to Hermosillo.[21][37]

During the regime of Porfirio Díaz from the late 19th century to the 20th century, major economic changes occurred. These changes promoted rapid economic growth, which had far-reaching social and political consequences. Sonora and the rest of the northern states rapidly increased in economic importance. Development of a rail system integrated the state's economy into the national, and also allowed greater federal control over all of Mexico's territory. After 1880, this rail system was extended north into the U.S., making it an important part of binational economic relations to this day.[38] However, the changes also permitted foreigners and certain Mexicans to take over very large tracts of land in Mexico. In Sonora, Guillermo Andrade controlled 1,570,000 hectares (15,700 km2; 6,100 sq mi), Manuel Peniche and American William Cornell Green about 500,000 hectares (5,000 km2; 1,900 sq mi). Foreign industry owners also tended to bring in Asian and European workers.[21] Chinese immigration into Sonora would begin at this time, and the Chinese soon became an economic force as they built small businesses that spread wherever economic development occurred.[39]

The appropriation of land for both agriculture and mining placed renewed pressure on the Yaquis and other native peoples of Sonora. Previously, active resistance had given the Yaqui fairly autonomous control of a portion of the state and kept their agricultural system along the Yaqui River. Encroachment on this land led to uprisings and guerilla warfare by the Yaquis after 1887. By 1895, the federal and state governments began to violently repress the Yaquis and forcefully relocate captured Yaquis to the plantations in Mexico’s tropical south, especially the henequen plantations in the Yucatán Peninsula. The Yaqui resistance continued into the 20th century, with the expulsions reaching a peak between 1904 and 1908, by which time about one quarter of this population had been deported. Still more were forced to flee into Arizona.[40]

20th century

The policies of the Díaz government caused resentment not only among the Yaquis, but also throughout the country.[41] One of the preludes to the Mexican Revolution was the 1906 Cananea miner's strike. Approximately 2,000 strikers sought negotiations with American mine owner William Greene, but he refused to meet with them. The strike quickly turned violent when the miners tried to take control of the mine and gunfire was exchanged. Greene requested help from federal troops, but when it was obvious they could not arrive in time, he appealed to the governments of Arizona and Sonora to allow Arizona volunteers to assist him. This increased the scale of the violence. When Mexican federal troops arrived two days later, they put everything to a brutal end, with the suspected leaders of the strike executed. The heavy-handed way in which Díaz had handled the strike made resentment against Diaz grow, with more strikes beginning in other areas.[42][43]

In late 1910, the Mexican Revolution began in earnest, and Díaz was quickly deposed. The governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, sought refuge in Sonora, and became one of the principal political leaders during the rest of the war, with his main base of operations in Hermosillo. A number of the revolutionary leaders who joined Carranza in Sonora did not come from peasant backgrounds, but rather the lower middle class of hacienda-managers, shopkeepers, mill-workers, or schoolteachers, who opposed large-scale landowners and the Porfirian elite.[44] After Díaz was deposed, Carranza competed for power against Álvaro Obregón and others.[43] The Yaquis joined with Álvaro Obregón’s forces after 1913.[41]

By 1920, Carranza had become president of Mexico, but found himself opposed by Obregón and others. Carranza tried to suppress political opposition in Sonora, which led to the Plan of Agua Prieta, which formalized the resistance to Carranza by Obregón and his allies (primarily Abelardo L. Rodríguez, Benjamín Hill and Plutarco Elías Calles). This movement soon dominated the political situation, but it caused widespread political instability in doing so.[45] Obregón deposed Carranza and became the next president of Mexico. For the 1924 presidential elections, Obregón chose to succeed himself Plutarco Elias Calles, who was also a revolutionary leader from Sonora.[46] This effectively ended the war, but hostilities had again destroyed the Sonoran economy.[43] From 1920 to the early 1930s, four Sonorans came to occupy the Mexican presidency: Adolfo de la Huerta, Obregón, Calles and Rodríguez.[26]

The Chinese first arrived at Guaymas in the late 19th century and congregated there and in Hermosillo. Over the following decades, they moved into growing communities such as Magdalena and Cananea. Rather than working in the fields, most started their own small businesses, networking with other Chinese.[34] These business spanned a wide range of industries from manufacturing to retail sales of nearly every type of merchandise.[47] The Chinese in Sonora not only become successful shopkeepers, they eventually came to control local small businesses in many areas of the state.[48] By 1910, the Chinese population in Sonora was 4,486 out of a total population of 265,383, making them the largest foreign presence in the state, with only North Americans a close second at 3,164. Almost none were female, as there were only 82 Chinese females in the entire country at the time. The Chinese population reached its peak in 1919 with 6,078 people, again with almost no Chinese women.[48]

Resentment against Chinese success began quickly, and Sinophobia rose sharply during the Mexican Revolution as many Chinese prospered despite the war, and many attacks were targeted against them.[47] The first organized anti-Chinese campaign in Sonora began in 1916 in Magdalena.[49] A more serious campaign began in 1925, calling for their expulsion from the state.[50] Mass expulsions were mostly carried out in Sonora and Sinaloa, partly because of their large populations, but the Chinese, often with their Mexican wives and children, were deported from all over the country. Some were returned to China but many others were forced to enter the U.S. through the border with Sonora, even though Chinese exclusion laws were still in effect there.[51] Sonoran governor Rodolfo Elias Calles was responsible for the expulsion of most Chinese-Mexican families into U.S. territory. Despite the diplomatic problems this caused, Elias Calles did not stop the expulsions until he himself was expelled from Sonora. However, by that time almost all of Sonora’s Chinese-Mexicans had disappeared.[52] By the 1940 census, only 92 Chinese were still living in Sonora, with more than two-thirds of these having acquired Mexican citizenship. This had the unintended consequence of nearly collapsing the Sonoran economy.[53]

The efforts at modernization and economic development begun in the Díaz period would continue through the Revolution and on through the rest of the 20th century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the process of electrification greatly increased the demand for copper, which led to a boom in mining in Sonora and neighboring Arizona. Cananea grew very quickly from a village of 900 to a city of 20,000. It also led to a network of roads, railroads and other connections across the border.[54] However, organized development of the state’s agriculture was put on hold because of the Revolution, the Great Depression and other political upheavals.[55]

In the 1930s, Sonora benefitted from a number of national policies aimed at developing the cities on the border with the U.S. and at building a number of dams to help develop agriculture and the general water supply.[56] Major agricultural reform was begun in the 1940s in the Mayo River area, when the delta was cleared of natural vegetation and made into farmland. Water for these farms was secure through the building of the Mocúzari Dam about 15 miles (24 km) from Navojoa. When it was completed in 1951, there was a system of canals, wells and highways to support large-scale agriculture for shipment to other places.[55]

In the last half of the 20th century, the state's population has grown and foreign investment has increased due to its strategic location along the border and its port of Guaymas. More than 200 international and domestic enterprises moved into the state, allowing for the development of modern infrastructure such as highways, ports and airports, making the state one of the best connected in the country. A bridge was built over the Colorado River to link Sonora with neighboring Baja California in 1964. One important sector of the economy has been industry, culminating in the Ford automotive plant in Hermosillo and a number of assembly plants called maquiladoras on the border with the U.S. One of the fastest growing sectors of the economy has been tourism, now one of the most important sectors of the economy, especially along the coast, with the number of visitors there increasing every year. This has led to a surge in hotel infrastructure, especially in Puerto Peñasco.[56]

For most of the 20th century, Mexico was dominated by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Discontent with this one-party system became prominent in the northern states of Mexico, including Sonora. As early as 1967, a competing party, the National Action Party (PAN), won control of the city government of Sonora's capital, Hermosillo.[57] PAN won important municipal victories in the state in 1983, which President de la Madrid refused to officially recognize but was forced to let stand.[58] PAN's growing strength by the 1980s forced the PRI to nominate candidates who were similar to PAN, successful business executives who favored economic liberalization over traditional Mexican statism, preferred in the north of the country. Institutional Revolutionary Party won the Sonoran gubernatorial race in 1985, but it was heavily contested with obvious problems of fraud.[59] By the 1990s, PRI operatives caught manipulating election results were actually prosecuted by the Sonoran state attorney.[60] This along with other events in the country eventually led to the end of the one-party system when Vicente Fox was elected president in 2000. PAN has since dominated most of the north of the country, but Sonora did not have its first PAN governor until 2009, with the election of Guillermo Padrés Elías.[61]

Sonora's border with Arizona has received more attention since 2000, with the increase of illegal border crossings and drug smuggling, especially in rural areas such as around Naco, which is one of the main routes into the U.S.[62] Starting in the 1990s, increased border patrols and the construction of corrugated metal and chain link fences in California and Texas dramatically cut illegal border crossing in these two states. This led illegal immigrants into the more dangerous desert areas of Arizona and New Mexico, which have mostly seen rises in illegal crossings since then.[63][64] Many migrants now come to the Arizona border between Agua Prieta and Nogales, with Naco as one of the preferred routes for "coyotes" (also called "polleros" or "enganchadores") or smugglers who offer to take migrants across.[62][65] Migrant shelters and hotel in border towns cater to those waiting to cross into Arizona.[66] Providing lodging for migrants is a growing business in Naco and other border towns, where the rate is between 200 and 300 pesos per night per person. Many of these lodgings are filled with people who cannot cross the border.[65] One example is the Hospedaje Santa María, which is a run-down, two-story building.[64]

Forty-five percent of the deaths of migrants occur on the Arizona side of the border.[65] According to Arizonan authorities, 2010 was a record year for deaths in Arizona for people crossing illegally from Sonora, with the bodies of 252 crossers found in the deserts between the New Mexico and California borders. This broke the previous record of 234 in 2007, with nearly 2,000 found in this area since 2001.[67] However, Mexican officials state that the figures are higher, with over four hundred dying in Arizona deserts in 2005 alone. In 2006, Mexican officials began to distribute maps of Arizona to Mexicans gathered in Sonoran border town with the intention of crossing illegally. The Mexican government stated the reason for the maps was to help Mexican avoid dangerous areas that have caused deaths from the desert's heat.[66]

Migration and drug smuggling problem has affected most border towns. Many people make a living by catering migrants or working as "coyote" guides.[64] People hoping to cross the border and those recently deported crowd the border area; some of these people return home, but many others decide to stay on the Sonoran border, working to earn money for another attempt. These workers put a strain on insufficient municipal medical services.[65] The walls, which have shut down much of the illegal crossing into Texas and California, have also been built on parts of the Arizona border, especially between towns such as the two Nacos and the two Nogaleses. The wall in Naco is four meters high and made of steel. It currently extends 7.4 kilometres (4.6 mi), but there are plans to extend it another 40 kilometres (25 mi). Security there was further tightened after the 2001 September 11 attacks. The U.S. Border Patrol credits the wall and better surveillance technology with cutting the number of captured border crossers near Naco by half in 2006. People on both sides of the wall have mixed feelings about it.[64]

Violence connected to drug smuggling on the border and in Mexico in general has caused problems with tourism, an important segment of the entire country. Federal troops have been stationed here due to the violence, which has the population divided. While the security they can provide is welcomed, there is concern about the violation of human rights. In 2005, the state began advertising campaigns to reassure Arizonans that it is safe to cross the border.[68][69]

Geography and environment

Natural divisions

Sonora is located in northwest Mexico. It has a territory of 184,934 square kilometres (71,403 sq mi) and is the second largest state of the country.[37][70] It borders the states of Sinaloa, Chihuahua, and Baja California Norte, with the U.S. to its north and the Gulf of California to its west.[70] Its border with the U.S. is 588 kilometres (365 mi) long.[37] The state is divided into five hydraulic regions – Río Colorado, Sonora Norte, Sonora Sur, Sinaloa, Cuencas Cerradas del Norte.[37][71]

The state's geography is divided into three regions created by the rise of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains and the separation of the Baja California Peninsula, with all three running roughly north-south. The mountains dominate eastern Sonora, while the center is dominated by plains and rolling hills, which then extend west to the coast on the Gulf of California.[37][72]

Center plains and coast

The center plains and coastline were both created by the tearing away of the Baja California Peninsula between ten and twelve million years ago. These plains are between 50 kilometres (31 mi) and 120 kilometres (75 mi) wide, wedged between the Sierra Madre and the Gulf of California, which began to form between 5.5 and 6 million years ago. Climate patterns bring moisture east from the Pacific Ocean, forming rivers and streams that cross the plains area and empty into the gulf. These rivers have brought down sediment from the volcanic rock of the Sierra Madre and eventually buried most of the mountains and hills of the center of the state, smoothing them into plains. These soils are rich in clays and thousands of feet thick in places, making this region very fertile, only lacking water.[72]

The state has 816 kilometres (507 mi) of coastline, all of which faces the Gulf of California, with its relatively shallow and very calm waters.[37] There are beaches along most of this coastline, some of which with fine, white sand. The best known of these are San Carlos, Puerto Peñasco and Bahía Kino. San Carlos, with its Los Algodones Beach is one of the most visited areas on the Sonoran coast. Los Algodones ("The Cottons") is named for its dunes of white sand, which can be compared to cotton balls. San Carlos has a large variety of sea life off its shores, making it popular for sports fishing and scuba diving. A number of Yaquis, Seris and Guaymas on and around the Tetakawi Hill, making a living from fishing.[73][74]

Puerto Peñasco is located in the extreme northwest of the state in the Upper Gulf somewhat near where the Colorado River empties. It contains 110 kilometres (68 mi) of beaches on calm seas, located in the Altar Desert near El Pinacate biosphere reserve, with some of the driest climates in Mexico. Since the 1990s, it has experienced large-scale development along its 110 kilometres (68 mi) of beaches, which have calm seas. The area has experienced a building boom since the 2000s.[73] However, as of late 2013, many buildings are vacant, for sale, or neglected due to the suppressed economic conditions and the corresponding decline in tourism.

Bahía Kino is located near San Carlos, with a dock located in the community of Kino Viejo. This bay's beaches have white sand, with warm calm waters off of them. For this reason, Bahía Viejo calls itself la perla del Mar de Cortés ("the pearl of the Gulf of California"). The area is popular for scuba diving and sports fishing as its waters are filled with various species of multicolored fish, small invertebrates, large crustaceans, manta rays, sponges and turtles. On the neighboring islands, sea lions can be seen. Off this coast is the Isla Tiburón, Mexico’s largest island and a nature reserve with wild sheep and deer. There are indigenous communities here, especially at Punta Chueca, which still practice hunting, fishing and collecting natural resources, as well as selling crafts to tourists.[73][75]

Lesser known beaches include El Desemboque, El Himalaya and Huatabampito. El Desemboque is a small Seri village with beaches located 370 kilometres (230 mi) northwest of Hermosillo, just south of Puerto Libertad. Activities in the area include scuba diving and swimming in isolated and relatively undeveloped beaches. The current name is from Spanish (disembarkation point), but the Seri name for the area means "where there are clams."[76] El Himalaya Beach is located forty km from Guaymas. It is a semi virgin beach surrounded by calm waters, mountains, and unusual species of flora and fauna and cave paintings. The area is filled with large stone yellow-red rock formations that were created by a volcanic eruption.[77] Huatabampito is an area of beaches in the south of the state. The beaches have delicate dune of fine sand and the waters are clear with a green-blue color. Each year, whales arrive to this area to reproduce in the warm waters. This is the main attraction, bringing visitors from Mexico and abroad.[78]

Sierra Madre Occidental

The east of the state is dominated by the Sierra Madre Occidental, which has less extreme temperatures and, due to the high altitude, relatively more rainfall.[70] As moist air masses move inland from the Pacific and the tropics and are forced against the mountains, they cool and this leads to precipitation, mostly rain but occasional snows in the highest regions. This process takes most of the moisture out of the air and feeds the various rivers and streams, which empty into Gulf as well as underground aquifers that are under the coastal plain.[79]

Flora and fauna

Habitats and vegetation vary greatly depending on elevation and rainfall.[80] An estimated 2,230,000 hectares (22,300 km2; 8,600 sq mi) of Sonora is in arid grasslands; 1,200,000 hectares (12,000 km2; 4,600 sq mi) are covered in forests, 301,859 hectares (3,018.59 km2; 1,165.48 sq mi) in rainforest and 1,088,541 hectares (10,885.41 km2; 4,202.88 sq mi) in farmland. Seventy percent of the territory, or 13,500,000 hectares (135,000 km2; 52,000 sq mi), is covered in desert vegetation or arid grasslands.[37] The Yécora municipality in eastern Sonora has one of the highest grass diversities in Mexico.[81] There are eight types of desert vegetation, seven of which are native to the Sonora Desert and one in the area that transitions to the Chihuahua Desert. Most are scrubs or small bushes, which generally do not reach over 4 metres (13 ft) in height, most of the rest are cactus, with some mangroves and other halophile plants.[37] Many plants are rainfall sensitive, with most trees and shrubs growing leaves and flowers just before or during the rainy season, then drop their leaves afterwards. However, there are plants in flower at one time or another throughout the year.[82] Coastal plants receive less water stress due to lower evaporation rates, and substantial moisture from dew, especially in the cooler months.[83]

Most forests are located in the northeast of the state, covering about 6.4% of the state. This is the area with the coolest temperatures.[37] Deforestation has been a significant problem, especially after 1980, because the rate of cutting trees has increased. In central Sonora, the area covered by Madrean evergreen woodland and Sonoran Desert scrub decreased 28% and 31%, respectively, between 1973 and 1992 (ValdezZamudio et al. 2000). During this same period,[84] For example, much of the forests of mesquite trees in the lower elevations of the state have disappeared because of the demand for local fuels and the market for mesquite charcoal in Mexico and the U.S.[85]

Most of northern Mexico suffers from one of the world’s highest rates of desertification due to land degradation in arid and semi arid areas, with the loss of biological and/or economic productivity, but the process is most severe Sonora as neighboring Sinaloa. Land degradation occurs because of clearing land for agriculture, the planting of non-native buffelgrass for grazing, the cutting of forests, overgrazing of natural vegetation and soil salinization from irrigation. A study by Balling in 1998 showed higher soil and air temperatures in areas that have been overgrazed, deforested and otherwised cleared land, likely due to the lack of shading vegetation, which leads to higher soil evaporation and desert conditions. Studies have also indicated that warming trends are higher in Sonora than in neighboring Arizona, into which the Sonora Desert also extends.[84]

The state contains 139 species and subspecies of native mammals, with the most important being white tailed deer, mule deer, wild sheep, bats, hares, squirrels, moles, beavers, coyotes, wolves, foxes, jaguars, and mountain lions. Amphibians and reptiles include frogs and toads, desert tortoises, chameleons, gila monsters, rattlesnakes and other types of snakes. The number of bird species native to the state is not known, but major species include roadrunners, quail, turkeys, buzzards and doves.[37]

Climate

During the Pliocene, the detachment of Baja California, the development of the Gulf of California and the Subartic California current drastically reduced moisture coming into Sonora leading to severe regional aridity in both this state and neighboring Baja California. This created xeric communities and the development of species endemic only to this region.[86]

There are four major climate regions in the state: dry desert (Köppen BW), arid lands (BS), semi moist lands, and temperate zones (Cwb).[87] Ninety percent of the state has desert or arid conditions. The other two climates are restricted to the areas of the state with the highest altitude such as the Yécora area, the mountains north of Cananea and a strip along the southeast of the state on the Chihuahua border.[37][70]

Average high temperatures range from 12.7 °C (54.9 °F) in Yécora to 35 °C (95 °F) in Tesia, municipality of Navojoa. Average low temperatures range from 5.9 °C (42.6 °F) in Yécora to 35.2 in Orégano, municipality of Hermosillo.[37][70] In the winter, cold air masses from the north reach the state, and can produce below freezing temperatures and high winds at night in the higher elevations, but the temperature can then jump back up to over 20C during the day. Freezing temperatures in the lowlands almost never occur.[80][88] In February 2011, the Mexican government recorded a low in Yécora of −12C.[88]

Precipitation is seasonal and most occurs in the higher elevations. In hot and arid or semi arid lands, evaporation vastly exceeds precipitation.[89] Mexico’s most arid area, the Altar Desert is located in this state.[70] The east of the state is dominated by the Sierra Madre Occidental, which has less extreme temperatures and relatively more rainfall due to altitude.[70] Most moisture comes in from the Pacific Ocean and the tropics, which is pushed against the Sierra Madre. This cools the air masses, leading to rain and occasionally snow in the higher elevations. While most of the rain falls in the mountainous areas, much of this water finds its way back to the western coastal plains in the form of rivers and streams that empty into the Gulf of California and fill underground aquifers.[79] Most of the year’s precipitation falls during the rainy season, which is locally called “las aguas” (the waters). These last from July to mid September, when monsoon winds bring moist air from southerly tropical waters. Most of this is from the Pacific Ocean west of Central America but can also come from Gulf of Mexico as well. This moister flow results in nearly daily afternoon thunderstorms. After the las aguas, there may be additional moisture brought in by hurricanes, which generally move west along the Pacific coast of Mexico and occasionally come inland, especially in southern Sonora. However, these storms tend to drop large quantities of rain in a short time, causing flooding and destruction.[83]

In the winter, from November to February, there are light rains called equipatas ("horse hoofs", named after the sound the rain makes). These rains come in from the north from the southern extensions of frontal storms that originate in the northern Pacific Ocean. These end by March or April when the fronts are no longer strong enough to reach this far south. They end even earlier in the extreme south of the state as the storm systems retreat, with the dry season lasting eight or nine months in this part of the state. In the north these rains support a wide variety of spring annuals and wildflowers, but the water they supply in the south of the state is still important to help replenish wells.[83]

Hydrology

With the exception of the Colorado River, river and aquifer systems in Sonora are a result of rains from incoming clouds rising above the Sierra Madre Occidental. This water runs down the west side of the mountains along the canyons and valleys towards the plains and coast and into the Gulf of California,[79] Sonora has seven major rivers – the Colorado River, the Concepción River, the San Ignacio River, the Sonora River, the Mátepe River, the Yaqui River and the Mayo River. Dams, such as Alvaro Obregon, Adolfo Ruiz Cortines, Plutarco Elias Calles, Abelardo Rodriguez and Lazaro Cardenas, have been built along some of these rivers, at least two of them where natural lakes existed.[37][87] Some of the dams formed large deltas, such as that of the Mayo River.[28] The largest aquifers are mostly found between Hermosillo and coast, the Guaymas Valley and the area around Caborca. Most of these are having problems due to overpumping for agricultural irrigation.[37]

Protected areas

Sonora has 18,463 square kilometres (7,129 sq mi) of protected wildlife areas.[90] Protected natural areas in the state are of three types: biosphere reserves, areas for the protection of flora and fauna and areas for the protection of natural resources.[91] The El Pinacate biosphere reserve is located between Puerto Peñasco and the U.S. border in the Altar Desert. The reserve consists of an area with a series of gigantic dormant volcanic craters, which are covered with flora and fauna. It is frequently visited by foreign tourists, researchers and photographers. The reserve has a site museum, which displays the area history from its formation to the present. The craters are named Badillo, Molina or El Trébol, Cerro Colorado, Volcan Grande, Caravajales and the largest, Mc Dougal.[92]

The Cañón las Barajitas ("Barajitas Canyon") is a protected natural area which consists of three different ecosystems, located 31 kilometres (19 mi) north of San Carlos. It contains a kilometer of beaches and a canyon which has two distinct microclimates, one arid and desert-like and the other subtropical. The area was a wide variety of fauna including whales, dolphins and manta rays that can be seen off the coast depending on the season. Activities for visitors include kayaking, paddleboats, scuba diving and fishing. There are also caves as well as a solor observatory.[93]

The Alto Golfo y Delta ("Upper Gulf and Delta") biosphere reserve encompasses is in the northwest of Sonora and northeast of Baja California Norte at the northernmost part of the Gulf of California and the delta of the Colorado River. The area is home to a very large number of marine species. There are also rocky beaches along with those with fine sand. Some of these are home to groups of seals and sea lions. The reserve was created in 1993 and encompasses an area of 934,756 hectares. On land, there are arid scrubbrush, coastal dunes and an estuary. It extends into the far upper part of the Gulf of California.[94]

The Bahía e islas de San Jorge ("Bay and Islands of San Jorge"), covering 130 square kilometres (50 sq mi), are located on Sonora’s northern coast between Caborca and Puerto Peñasco. The islands were first made a federal reserve in 1978 due to its important to migratory birds. They are especially important to species such as the Sterna antillarum, colonies of Sula leucogaster, Myotis vivesi and Zalophus californianus. The islands are large rocks and are white from guano. The beaches extend for ten km and end at the bay of San Jorge on the south end. The area is home to sea lions and a type of bat that fishes. There are sand dunes with arid zone vegetation as well as a small estuary. The climate is very arid and semi hot with an average temperature of between 18 and 22 °C (64 and 72 °F).[95]

The Isla Tiburón is an ecological resereve with about 300 species of plants with desert and marine wildlife. The island was once inhabited by the Seris, and they still consider it their territory.[96]

The La Mesa el Campanero-Arroyo El Reparo reserve is found in the municipality of Yécora. It is a mesa with mountains which cover 43,000 hectares (430 km2; 170 sq mi), containing pine and tropical forests, rivers, arroyos, rock formations and dirt roads. Due to its altitude of between 700 and 2100 masl, its temperatures are temperate for the state. It is part of the Sierra Madre Occidential bio region and in the upper basins of the Yaqui and Mayo rivers.[97]

Politics and government

Sonora is divided into 72 municipalities.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

The border

Sonora's border with the U.S. is 588 kilometres (365 mi) long,[37] and runs through desert and mountains, from the western Chihuahuan Desert, through an area of grasslands and oak mountain areas to the Sonoran Desert west of Nogales. The area gets drier from here west and the last third of the border is generally uninhabited. There are six official border crossings. From east to west these at Agua Prieta, Naco, Nogales, Sasabe, Sonoyta and San Luis Río Colorado. In populated areas, much of the border is marked by corrugated metal walls, but most of the rest is marked by barbed wire fence and border monuments.[98]

Like others in the world, the border is a culture unto itself, not belonging 100% to either country. Interaction between the peoples on both sides is a part of both the culture and the economy. In the 1980s, an international volleyball game was regularly held near Naco, with the chain link border fence serving as the net. Much of Arizona and Sonora share a cuisine based on the wheat, cheese and beef that was introduced to the region by the Spaniards, with wheat tortillas being especially large on both sides of the border. This diet is reinforced by the vaquero/cowboy tradition which continues in both states.[98] The six border crossings are essential to the existence and extent of the communities that surround them, as most of them function as ports for the passage of goods between the two countries.[99] People regularly shop and work on the other side, taking advantage of opportunities there.[98] The economic opportunities of the border are not equal on both sides. Most of the population along this border lives on the Sonoran side, many of which have moved here for the opportunities created by the maquiladoras and other businesses. These are lacking on the Arizona side.[99]

The border has separated the region’s indigenous populations, such as the Tohono O’odham. While members of the Tohono O’odham have special border crossing privileges, these have become endangered as Mexican farmers encroach on tribal lands in Sonora, which are vulnerable to drug smugglers. Yaquis in Arizona travel south to the Yaqui River area for festival, especially Holy Week, and Yaquis travel north to Arizona for cultural reasons as well. When Father Kino arrived in this area, he named much of it the Pimería Alta, as Pima territory extends from the highlands of eastern Sonora up towards Tucson.[98]

Authorities on each side work to keep out from the other that which is undesirable. For the U.S., this mostly involves drugs and illegal immigrants. For Mexico, this mostly involves struggling against the importation of untaxed goods, especially automobiles. Smuggling people and drugs into the U.S. is big business in Mexico, but while it affects everyone living on the border, it is generally not seen, except for occasional newspaper headlines, occasional violent crime and religious articles geared to those in the trade. Illegal crossings taking place through tunnels, hidden cars and trucks or most commonly, simply passing through a gap in the fence, especially in the more remote areas. In 1990, a tunnel linking two warehouses in Agua Prieta and Douglas, AZ was discovered. It was sophisticated with hydraulic equipment and means to move large quantities of goods. At least three corridos have been written about this tunnel.[98]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1895[100] | 192,721 | — |

| 1900 | 221,682 | +15.0% |

| 1910 | 265,383 | +19.7% |

| 1921 | 275,127 | +3.7% |

| 1930 | 316,271 | +15.0% |

| 1940 | 364,176 | +15.1% |

| 1950 | 510,607 | +40.2% |

| 1960 | 783,378 | +53.4% |

| 1970 | 1,098,720 | +40.3% |

| 1980 | 1,513,731 | +37.8% |

| 1990 | 1,823,606 | +20.5% |

| 1995 | 2,085,536 | +14.4% |

| 2000 | 2,216,969 | +6.3% |

| 2005 | 2,394,861 | +8.0% |

| 2010 | 2,662,480 | +11.2% |

| 2015[101] | 2,850,330 | +7.1% |

General population

Economic growth in the state since the Mexican Revolution has led to steady population growth. However, this population growth has been concentrated on the arid coastline due to the dominant agriculture and fishing industries. Eighty five percent of Sonora’s population growth since 1970 has been in this area.[102] Another area where there have been gains are municipalities with industry, such as in Hermosillo and along the U.S. border. However, those municipalities with none of these economic advantages do not see population growth and some see population decreases.[103] Despite population growth, Sonora is still one of the least densely populated states in the country.[102] About 90% of the state’s population is Catholic, with about 5% belonging to Evangelical or Protestant groups and over 7% professing some other faith.[103]

The 1921 census reported Sonora's population as 55.84% white, 30.38% mixed indigenous and white, and 13.78% indigenous.[104]

Indigenous population

The most numerous indigenous groups in the state are the Mayo, the Yaquis and the Seris; however there are a number of other groups which have maintained much of their way of life in territory in which they have live in for centuries.[105] There were at least nine tribes, eight of which remain today. Seven are indigenous to Sonora, with one migrating to the state over a century ago from the U.S.[106] These cultures generally hold in reverence the deserts, mountains, riverbeds and Gulf of California with which they have contact. Many of these beliefs have been adapted to Catholicism. There are efforts to preserve indigenous languages, but with groups of diminished size, this has been a challenge.[105] As of 2000, there were 55,609 people, or 2.85% of the population, who spoke an indigenous language in the state. The indigenous population is concentrated in fourteen municipalities, which are home to 91% of the total indigenous population of the state. The municipalities with the greatest presence include Etchojoa with 19% of the municipal population, Guaymas with 8.34%, Huatabampo with 11.8%, Navojoa with 5.92%, Hermosillo with 1.1%, Cajeme with 1%, Bácum with 9.26%, Benito Juárez with 5.2%, San Ignacio Río Muerto with 7.4%, Nogales with 1.2%, Álamos with 3.9%, San Miguel de Horcasitas with 13.7%, Yécora with 6.8% and San Luis Río Colorado with 5.1%.[103]

The Mayos are the most numerous indigenous ethnic group in the state with more than 75,000 who have maintained their language and traditions. These people, who call themselves Yoreme, are descended from ancient Huatabampo culture.[107][108] They are concentrated along the Mayo River. Most are found in the municipalities of Álamos, Quiriego and others in the south of the state, as well as in some parts of the coast near the Isla Tiburón. There is also a notable community in the northwest of Sonora.[107][108] Their religion is a mix of Catholicism and traditional beliefs, which they assimilated along with European farming and livestock knowledge. Mayo houses often have a cross made of ironwood to protect against evil. Ethnically pure Mayos tend to segregate themselves from mestizos and other ethnicities.[107][108] The Mayos make their living from subsistence farming, working on larger farms and combing wild area for herbs, fruits and other resources. They also work making crafts in wood making utensils and decorative items.[28]

The Yaquis are the indigenous group mostly closely associated with the state of Sonora.[109] These people are second most numerous in the state with about 33,000 members traditionally located along the Yaqui River. They are found principally in the communities of Pótam, Huíviris, Torim, Cocorit, Bácum, Vícam, Rahúm and Belem, which have semi autonomous government. The Yaqui have been able to maintain most of their traditions including ancestor worship, original language, and many of their traditional rites and dances, with the deer dance the best known among outsiders. The Yaquis call themselves and the Mayos the “Yoreme” or "Yoeme". The Yaqui and Mayo languages are mutually intelligible, and the two peoples are believed to have been united until relatively recently. One of the Yaqui religious celebrations which is best known among outsiders is Holy Week, along with rituals associated with Lent and Day of the Dead. As they consider the soul immortal, funerals are not a somber occasion but rather celebrations with banquets and music.[107] The preservation of history is important to the Yaqui, especially the struggles they have had to maintain their independence.[109]

The Seris call themselves the Comcáac,[110] which means “the people” in the Seri language. The name Seri comes from the Opata language and means “men of sand.”[111] There are about 650 Seri people today. They are well known among outsiders in the state because of their culture and the crafts they produce in ironwood. For centuries they have inhabited the central coast of the state, especially in Punta Chueca, El Desemboque and Kino Viejo as well as a number of islands in the Gulf of California in and around the Isla Tiburón. Generally, the Seris are the tallest of the indigenous peoples of the region, and the first Spaniards to encounter them described them as "giants."[citation needed] Their traditional diet almost entirely consisted of hunted animals and fish. However, this diet changed after the arrival of the Spaniards, when the use of firearms led to the extinction of many food animals. The Seris' traditional beliefs are based on the animals in their environment, especially the pelican and the turtle, with the sun and moon playing important roles as well.[111][112] Rituals are now based on Catholicism,[111][112] especially those related to birth, puberty and death, but they include traditional chants about the power of the sea, the shark and great deeds of the past. They are also known for the use of face paint during rituals which is applied in lines and dots of various colors.[111][112]

The Tohono O’odham, still referred to as the Pápago by Spanish speakers, have inhabited the most arid areas of the state, and are mostly found in Caborca, Puerto Peñasco, Sáric, Altar and Plutarco Elías Calles in the north of the state. However, most people of this ethnicity now live in neighboring Arizona. The Tohono O’odham have as a principle deity the “Older Brother,” who dominates the forces of nature. Among their most important rituals is one called the Vikita, which occurs in July, with dances and song to encourage rainfall during the area’s short rainy season. In July, during the full moon, a dance called the Cu-cu is performed, which is to ask for favors from Mother Nature so that there will be no drought and the later harvests will be abundant. The dance is performed during a large festival with brings together not only the Tohono O’odham from Sonora, but from Arizona and California as well. The feast day of Francis of Assisi is also important. Many of these people are known as skilled carpenters, making furniture as well as delicate figures of wood. There are also craftspeople who make ceramics and baskets, especially a type of basket called a “corita.”.[113][114]

The Opatas are location in a number of communities in the center and northwest of the state, but have been disappearing as a distinct ethnicity. This group has lost its traditional rituals, and the language died out in the 1950s. The name means “hostile people” and was given to them by the Pimas, as the Opatas were generally in conflict with their neighbors. They were especially hostile to the Tohono O’odham, who they depreciatingly refer to as the Papawi O’otham, or “bean people.” Today’s Opatas have completely adopted the Catholic religion with Isidore the Laboror as the ethnicity’s patron saint.[115][116]

The Pimas occupy the mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental in eastern Sonora and western Chihuahua state. The Pimas call themselves the O’ob, which means "the people." The name Pima was given to them by the Spaniards because the word pima would be said in response to most questions asked to them in Spanish. This word roughly means “I don’t know” or “I don’t understand.” The traditional territory of this ethnicity is known as the Pimería, and it is divided into two regions: the Pimería Alta and the Pimería Baja. The principle Pima community in Sonora is in Maycoba, with other communities in Yécora and its vicinity as well as the community of San Diego, where there is a center selling Pima handcrafts. Pima religion is a mix of traditional beliefs and Catholicism. One of the most important celebrations is the feast of Francis of Assisi, who has been adopted as the patron saint of the Pima. Another important festival is called the Yúmare, which has a variable date with the purpose of asking for an abundant harvest, especially corn. Festivals generally last four days and consist of chants and dances such as the Pascola, accompanies by a fermented corn drink called tesguino.[115][117]

The Guarijíos are one of the least understood groups in the state, and are mostly restricted to an area called the Mesa del Matapaco in the southeast. The Guarijíos are related to the Tarahumaras and the Cáhitas. This was the first group encountered by the Jesuits in 1620. Initially, they lived in the area around what is now Álamos, but when the Spaniards arrived, they were dispossessed of their lands. They also did not intermarry with the newcomers, isolating themselves. For this reason, people of this group have very distinct facial features, and have keep their traditions almost completely intact. They remain isolated but are known for their handcrafts. In the 1970s, there was oppression of this group, which was not formally recognized until 1976. In this year, they were granted an ejido.[115][118]

The Cocopah is the smallest native indigenous group to Sonora with about 170 members, who live mostly in San Luis Río Colorado, along the U.S. border, in addition to nearby communities in Arizona and Baja California. Their own name for themselves, Kuapak, means “which comes” and possibly refers to the frequent changes in the course of the Colorado River.[119] Traditional native dress is in disuse. It is characterized by the use of feathers and necklaces made of bones, and include nose rings and earrings with colorful belts for the men. The women used to wear skirts made of feathers. They still practice a number of traditional rituals such as cremation upon death so that the soul can pass on to the afterlife without the body encumbering it. Another traditional practice is the use of tattoos.[119][120]

The Kickapoos are not native to Sonora, but migrated here from the U.S. over a century ago. Today, they are found in the communities of El Nacimiento in the state of Coahuila, Tamichopa in the municipality of Bacerac, as well as on several different reservations in the U.S. However, the Kickapoo community in Sonora is in danger of disappearing. In the 1980s, there were attempts to gather these disparate groups into one community. Eighty members remain in Sonora and they have lost their ancestral language, which was part of the Algonquin family, with the last speaker dying in 1996, although the language is still widely spoken in other Kickapoo communities, especially in Coahuila. The Kickapoo community in Sonora has also lost much of their traditional culture.[119][121]

Economy

General profile

Despite a rough terrain and a harsh climate, Sonora, like the rest of the northern Mexico, is rich in mineral resources. This has led to a history of self-reliance, and many see themselves as the heirs to a pioneering tradition.[122] A large part of this is linked to the vaquero or cowboy tradition, as much of the state’s economy has traditionally been linked to livestock.[123] Sonorans and other norteños (northerners) have a reputation for being hard working and frugal, and being more individualistic and straightforward than other Mexicans.[122] Although most people in the state are employed in industry and tourism, the trappings of the cowboy, jeans, cowboy hats and pickup trucks, are still very popular.[123]

In 2000, the gross domestic product (GDP) of the state was 40,457 million pesos, accounting for 2.74% of the country's total.[124] In 2008, Moody’s Investor’s Service gave the state an A1.mx (Mexico) and Ba1 (global) ratings, based mostly on its strong economic base. The state has a highly skilled labor force, and strong ties to the U.S. economy, mostly due to its shared border with Arizona. This links affects various sectors of the state’s economy. Sonora is one of Mexico’s wealthier states with the GDP per capita about 15% higher than average, and GDP growth generally outpaces the rest of the country, with a growth of 8.4% in 2006 as compared to the national average of 4.8%.[125] The economic success of the state, especially its industrial and agricultural sectors, as well as the border, have attracted large numbers of migrants to the state, from the central and southern parts of Mexico.[126]

Agriculture and livestock

Agriculture is the most important economic activity in the state, mostly with the production of grains. The major agricultural regions include the Yaqui Valley, the Mayo Valley, the Guaymas Valley, the coast near Hermosillo, the Caborca coast and the San Luis Río Colorado Valley. These areas permit for large scale irrigation to produce large quantities of crops such as wheat, potatoes, watermelons, cotton, corn, melons, sorghum, chickpeas, grapes, alfalfa, oranges and more. In 2002, agricultural production included 1,533,310 tonnes (3.38037×109 lb) of wheat, 172,298 tonnes (379,852,000 lb) of potatoes, 297,345 tonnes (655,534,000 lb) of wine grapes (both red and white), 231,022 tonnes (509,316,000 lb) of alfalfa, 177,430 tonnes (391,170,000 lb) of oranges and 155,192 tonnes (342,140,000 lb) of watermelon.[124][127] Sonora and Baja California Norte are Mexico's two largest wheat-producing states,[128] with Sonora alone producing 40% of Mexico’s wheat.[129]

There is some small scale farming done in the state, especially in the highlands areas, growing corn and other staples mostly for auto consumption, highly dependent on the rainy season in the late summer as there is no irrigation. If these rains fail, the area suffers.[82] However, most of the agriculture continues to shift away from small farms producing for local markets to largescale commercial agro-industry.[129] Many of the country’s largest agribusiness farms are located in Sonora.[122] This agricultural production is concentrated in the lowlands areas, with much of the production exported to the U.S. This includes non-traditional crops such as fruits, nuts and winter vegetables such as tomatoes, especially since NAFTA.[129]

Irrigation is essential for reliable agriculture on the coastal lowlands of the state,[130] and large scale irrigation infrastruction is needed for large scale production. After the Mexican Revolution, the federal government took control of Sonora’s irrigation infrastructure and after World War II, began extensive dam and reservoir construction. From the 1940s to the 1970s, advanced in agricultural techniques were pioneered by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) based in Ciudad Obregón. This combined new varieties of wheat, with irrigation, fertilizers and pesticides to greatly increase production. Mexico went from a wheat importer in the 1940s to a wheat exporter in the 1960s.[129]

However, such intensive agriculture in such an arid area has had a significant negative impact of water supplies. Eighty-eight percent of all water taken from above and below the surface is used for agriculture. One third of aquifers are overdrafted, especially in Caborca, Guaymas and the coast near Hermosillo.[131] There have been water disputes in the state, notablely between officials from Hermosillo and the relatively water-rich Ciudad Obregón.[132] The overpumping has drastically lowered water tables and has increased soil salinity in many areas. In some areas, the tables have dropped by as much as one or two meters per year, making fresh water increasing unavailable and forcing the abandonment of croplands. For this reason, in the last quarter of the 20th century area under cultivation in Sonora dropped by more than 24%.[129]

The state still maintains its traditional livestock industry, especially in beef cattle, which has a national reputation for quality. In 2001, the state produced 1,477,686 heads of cattle, 1,229,297 pigs, 38,933 sheep, 33,033 goats, 83,260 horses and 11,988,552 heads of domestic fowl.[124] The availability of relatively inexpensive semiarid land, along with proximity to U.S. markets, concentrates livestock production in Sonora and other northern states.[133]

Fishing

Sonora is a major producer of seafood in Mexico with a developed fishing infrastructure.[124] The Gulf of California contains a large quantity of fish and shellfish, but major fishing did not begin in Sonora and neighboring Sinaloa until the mid 20th century. Today, some of Mexico’s largest commercial fisheries are in the state.[134] Sonora is one of Mexico’s leading fish producing states, with 70% of Mexico’s total coming from the Pacific coast, including the Gulf of California.[135]

Much of the catch is shrimp and sardines, with about three quarters exported to the U.S.[124][134] In 2002, the catch totaled 456,805 tons of seafood with a value of about 2,031 million pesos. In addition to what is caught at sea, there is active fish farming which raises mostly oysters and shrimp.[124] Much of the commercial and sports fishing is essentially unregulated and has had a very pronounced impact on the Gulf of California, with commercially important species such as shrimp, groupers, snappers, corvinas, yellowtail,[disambiguation needed] billfishes have been harvested well above sustainability. Two species which have been particularly hard hit are sharks and manta rays. In addition, shrimp trawling catches a large amount of non target species, which are discarded, and have destroyed large areas of the Gulf’s seafloor. All this has led to rapidly declining harvests.[134]

Industry and mining

Most of the industry of the state is related to agriculture and fishing, in food processing and packing.[124] In the 1980s, the state gained a large number of industrial plants called “maquiladoras,” mostly situated along the border and in the capital of Hermosillo.[124] These are assembly plants run by mostly U.S. companies, which have certain duty and tax breaks. By the end of the 20th century, these enterprises had a large influence on the expansion and modernization of the border area, including Sonora. They not only introduced new sources of employment, their U.S. management styles have had influence on business in the state and the rest of the north. However, maquiladoras peaked in 2001, and now many U.S. companies are moving production facilities to China. The number of maquiladoras has declined, but the value of their output has increased as those that remain shift to higher value-added goods and automation. In addition, many of the plants abandoned by U.S. companies have been taken over by Mexican firms. Despite the decline of maquiladoras, exports from them have risen 40%.[136]

In addition to livestock, mining is another traditional element of Sonora’s economy, beginning with a major find near the city of Álamos. While the silver of that area has mostly been depleted, Sonora still plays a large part in Mexico’s standing as one of the top fifteen producers of minerals in the world, leading in silver, celestite and bismuth. Sonora is the leading producer of gold, copper, graphite, molybdenum, and wollastonite. There are still deposits of silver in the Sierra Madre Occidental. Sonora also has one of the largest coal reserves in the country.[137] The state has the largest mining surface in Mexico,[137] and three of the country’s largest mines: La Caridad, Cananea and Mineria María. It is also home to North America’s oldest copper mine, located in Cananea.[138] Grupo México, with one of its principle mining operations in Cananea, is the world’s third-largest copper producer in the world.[139] In 2002, mines produced 6,634.5 kilograms of gold, 153,834 kilograms of silver, five tons of lead, 267,171 tons of copper, three tons of zinc, 18,961 tons of iron, 7,176 tons barium sulphate. However, annual production is heavily dependent on world market prices.[124]

Mexico’s mining industry was mostly dominated by the Spaniards during the colonial period, and then by foreign enterprises after Independence. In the 1960s and 1970s, the government forced out most foreign interests in Mexican mining, beginning with the increasing restriction of ownership in Mexican mining companies.[137] These restrictions were relaxed starting in 1992, with the only restriction that the operating company be Mexican. Within three years of the change, more than seventy foreign companies, mostly U.S. and Canadian enterprises, opened offices in Hermosillo.[138]

Major mining operations have had severe environmental impact, especially in the areas surrounding it, with Cananea as the primary example. Mining has been functioning here for over a century, with mining and smelter wastes polluting the San Pedro and Sonora Rivers near the mine, threatening both watersheds. Mining operations also destroy nearby forests due to the demand for building materials and fuel. Few old trees stand near the city of Cananea and the town of San Javier in central Sonora.[138]

Tourism

Business and leisure visitors to the state primarily come from Mexico (over 60%), with the majority of foreign visitors coming from the U.S., especially the states of Arizona, California and New Mexico. The four most important destinations in the state for leisure and business travelers include Nogales, Hermosillo, Guaymas and Puerto Peñasco, with beach destinations preferred by most leisure travelers. One advantage that Sonora has is its proximity to the U.S., from which come most of the world’s travelers. In second place are tourists from Canada, many of whom visit as part of cruises. U.S. tourists mostly visit Puerto Peñasco, San Carlos and Navajoa and prefer areas they consider friendly, with no “anti-U.S.” sentiment. Leisure visitors from the U.S. tend to be between 40 and 65 years of age, married or in a relationship, educated at the university level or higher, with about thirty days of vacation time, and they and primarily research travel options on the Internet. Most visit to relax and experience another culture. Most domestic visitors also use the Internet, with about half having a university education or higher and about half are married or with a partner. Most domestic visitors are on vacation with their families. The busiest domestic travel times are Holy Week, summer and Christmas, with the overall busiest months being January, April, July, August and December.[140]

In 2009, the state received 7,024,039 visitors, which added 20,635 million pesos to the economy. Most visitors are domesticspending an average of 742 pesos. Foreign visitors spend on average of 1,105 pesos. Most stay on average 3.3 nights. Just over half of toursts in the state arrive to their destinations by private automobile, followed by airplane and commercial bus.[140]

During the 2000s, Sonora has increased its tourism infrastructure. In the last half of the 2000s, Sonora has increased its network of highways from 3,600 kilometres (2,200 mi) to 4,500 kilometres (2,800 mi), accounting for 6.7% of all highways in Mexico. It ranks second in four-lane highways, surpassed only by Chihuahua. From 2003 to 2009 the number of hotels in the state has increased from 321 to 410 and the number of rooms from 13,226 to 15,806, over 20%. Most of these hotels and rooms are in Hermosillo (57 hotels/3232 rooms) followed by Puerto Peñasco (40/3158), Ciudad Obregón (41/1671), Guaymas/San Carlos (28/1590), Nogales (24/1185), Navojoa (15/637) and Magdalena de Kino (10/284).[140] The cities of Hermosillo, Ciudad Obregón, Guaymas, Nogales, San Luis Río Colorado, Puerto Peñasco, Bahía Kino and Álamos all have 5-star hotels.[124] There are 2,577 restaurants in the state with 1288 in Hermosillo.[140]

Hotel occupation went from 45% in 2003 to 57.7% in 2006 but dropped to 36% in 2009. The state’s tourism suffered in 2008 and 2009, mostly due to the economic downturn and the AHN1 influenza crisis, which brought hotel occupancy rates down about 30%.[140]

Sonora’s major tourist attraction is its beaches, especially San Carlos, Puerto Peñasco, Bahía Kino and the Gulf of Santa Clara in San Luis Río Colorado.[124] San Carlos has a large variety of sea life off its shores, making it popular for sports fishing and scuba diving. One of its main attractions is the Playa de los Algodones, called such because its sand dunes look like cotton balls. On one of hills behind it, there is a lookout point which allows for views of the area. A number of Yaquis, Seris and Guaimas on and around the Tetakawi Hill, making a living from fishing. Puerto Peñasco has recently experienced large scale development along its 110 kilometres (68 mi) of beaches, which have calm seas. It is located extreme northwest of the state. Some of the available activities include jet skiing, boating, sailing, sports fishing, scuba diving and snorkeling. It is located near El Pinacate biosphere reserve. There is also an aquarium called the Acuario de Cer-Mar, which is a research center open to the public. The aquarium has a number of species such as marine turtles, octopus, seahorses and many varieties of fish. Bahía Kino is named after the Jesuit missionary, who visited the area in the 17th century. In the 1930s, a group of fishermen established a village in what is now known as Kino Viejo. This bay’s beaches have white sand, with warm calm waters off of them. For this reason, Kino Viejo calls itself la perla del Mar de Cortés (the pearl of the Gulf of California). Available activities include horseback riding, scuba diving and sports fishing. The Isla Tiburón is 28 kilometres (17 mi) from Bahia Kino in the Gulf of California. It is the largest island of Mexico, measuring 50 by 20 kilometres (31 by 12 mi). It has been declared an ecological reserve to protect its flora and fauna, such as the wild rams and deer that live here.[73]