Soviet Navy

The Soviet Navy (Template:Lang-ru, literally "Military Maritime Fleet of the USSR") was the naval arm of the Soviet Armed Forces. Often referred to as the Red Fleet, the Soviet Navy was a large part of the Soviet Union's strategic plan in the event of a conflict with the United States, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), or another conflict related to the Warsaw Pact. The influence of the Soviet Navy played a large role in the Cold War, as the majority of conflicts centered around naval forces.

The Soviet Navy was divided into four major fleets: the Northern, Pacific, Black Sea, and Baltic Fleets; under separate command was the Leningrad Naval Base. The Caspian Flotilla was a smaller force operating in the land-locked Caspian Sea. Main components of the Soviet Navy included Soviet Naval Aviation, Naval Infantry (Soviet Marines), and Coastal Artillery.

Most of the Soviet Navy was reformed into the Russian Navy after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, while some elements became the basis of the Ukrainian, Azerbaijani and Georgian navies.

Early history

Russian Civil War

The Soviet Navy was based on a republican naval force formed from the remnants of the Imperial Russian Navy, which had been almost completely destroyed in the Revolution of 1917, the Russian Civil War, and the Kronstadt rebellion. During the revolution, sailors deserted their ships at will and generally neglected their duties. The officers were dispersed (some were killed by the Red Terror, some joined the "White" (anti-communist) armies, and others simply resigned) and most of the sailors left their ships. Work stopped in the shipyards, where uncompleted ships deteriorated rapidly.

The Black Sea Fleet fared no better than the Baltic. The Bolshevik revolution entirely disrupted its personnel, with mass murders of officers; the ships were allowed to decay to unserviceability. At the end of April 1918, German troops entered Crimea and started to advance towards the Sevastopol naval base. The more effective ships were moved from Sevastopol to Novorossiysk where, after an ultimatum from Germany, they were scuttled by Vladimir Lenin's order. The ships remaining in Sevastopol were captured by the Germans and then, after November 1918, by the British. On 1 April 1919, when Red Army forces captured Crimea, the British squadron had to withdraw, but before leaving they damaged all the remaining battleships and sank thirteen new submarines. When the White Army captured Crimea in 1919, it rescued and reconditioned a few units. At the end of the civil war, Wrangel's fleet, a White fleet, moved to Bizerta in French Tunisia, where it was interned.

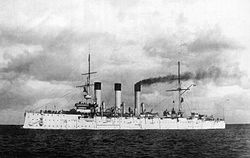

The first ship of the revolutionary navy could be considered the rebellious Imperial Russian cruiser Aurora, whose crew joined the Bolsheviks. Sailors of the Baltic fleet supplied the fighting force of the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution. Some imperial vessels continued to serve after the revolution, albeit with different names.

The Soviet Navy, established as the "Workers' and Peasants' Red Fleet" (Russian: Рабоче-Крестьянский Красный флот, Raboche-Krest'yansky Krasny Flot or RKKF) by a 1918 decree of the Soviet government, was less than service-ready during the interwar years.

As the country's attentions were largely directed internally, the Navy did not have much funding or training. An indicator of its reputation was that the Soviets were not invited to participate in negotiations for the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited the size and capabilities of the most powerful navies. The greater part of the old fleet was sold by the Soviet government to Germany for scrap. In the Baltic Sea there remained only three much-neglected battleships, two cruisers, some ten destroyers, and a few submarines. Despite this state of affairs, the Baltic Fleet remained a significant naval formation, and the Black Sea Fleet also provided a basis for expansion. There also existed some thirty minor-waterways combat flotillas.

Interwar period

During the 1930s, as the industrialization of the Soviet Union proceeded, plans were made to expand the Soviet Navy into one of the most powerful in the world. Approved by the Labour and Defence Council in 1926, the Naval Shipbuilding Program included plans to construct twelve submarines; the first six were to become known as the Dekabrist class.[2] Beginning 4 November 1926, Technical Bureau Nº 4 (formerly the Submarine Department, and still secret), under the leadership of B.M. Malinin, managed the submarine construction works at the Baltic Shipyard.[2] In subsequent years, 133 submarines were built to designs developed during Malinin's management. Additional developments included the formation of the Pacific Fleet in 1932 and the Northern Fleet in 1933. The forces were to be built around a core of powerful Sovetsky Soyuz-class battleships. This building program was only in its initial stages by the time the German invasion forced its suspension in 1941.

The Soviet Navy had some minor action in the Winter War against Finland in 1939–1940, on the Baltic Sea. It was limited mainly to cruisers and battleships fighting artillery duels with Finnish forts.[citation needed]

World War II: The Great Patriotic War

Building a Soviet fleet was a national priority, but many senior officers were killed in purges in the late 1930s.[3] The naval share of the national armaments budget fell from 11.5% in 1941 to 6.6% in 1944.[4]

When Germany invaded in 1941 and captured millions of soldiers, many sailors and naval guns were detached to reinforce the Red Army; these reassigned naval forces had especially significant roles on land in the battles for Odessa, Sevastopol, Stalingrad, Novorossiysk, Tuapse, and Leningrad. The Baltic fleet was blockaded in Leningrad and Kronstadt by minefields, but the submarines escaped. The surface fleet fought with the anti-aircraft defence of the city and bombarded German positions.[5]

The U.S. and Britain through Lend Lease gave the USSR ships with a total displacement of 810,000 tons.[6]

The composition of the Soviet fleets in 1941 included:[7]

- 3 aged battleships,

- 7 cruisers (including 4 modern Kirov-class heavy cruisers),

- 59 destroyer-leaders and squadron-destroyers (including 46 modern Type 7 and Type 7U destroyers),

- 218 submarines,

- 269 torpedo boats,

- 22 patrol vessels,

- 88 minesweepers,

- 77 submarine-hunters,

- and a range of other smaller vessels.

In various stages of completion were another 219 vessels including 3 battleships, 2 heavy and 7 light cruisers, 45 destroyers, and 91 submarines.

Included in the totals above are some pre-World War I ships (Novik-class destroyers, some of the cruisers, and all the battleships), some modern ships built in the USSR and Europe (like the Italian-built destroyer Tashkent[8] and the partially completed German cruiser Lützow). During the war, many of the vessels on the slips in Leningrad and Nikolayev were destroyed (mainly by aircraft and mines), but the Soviet Navy received captured Romanian destroyers and Lend-Lease small craft from the U.S., as well as the old Royal Navy battleship HMS Royal Sovereign (renamed Arkhangelsk) and the United States Navy cruiser USS Milwaukee (renamed Murmansk) in exchange for the Soviet part of the captured Italian navy.

In the Baltic Sea, after Tallinn's capture, surface ships were blockaded in Leningrad and Kronstadt by minefields, where they participated with the anti-aircraft defense of the city and bombarded German positions. One example of Soviet resourcefulness was the battleship Marat, an aging pre-World War I ship sunk at anchor in Kronstadt's harbor by German Stukas in 1941. For the rest of the war, the non-submerged part of the ship remained in use as a grounded battery. Submarines, although suffering great losses due to German and Finnish anti-submarine actions, had a major role in the war at sea by disrupting Axis navigation in the Baltic Sea.

In the Black Sea, many ships were damaged by minefields and Axis aviation, but they helped defend naval bases and supply them while besieged, as well as later evacuating them. Heavy naval guns and courageous sailors helped defend port cities during long sieges by Axis armies. In the Arctic Ocean, Soviet Northern Fleet destroyers (Novik-class, Type 7, and Type 7U) and smaller craft participated with the anti-aircraft and anti-submarine defense of Allied convoys conducting Lend-Lease cargo shipping. In the Pacific Ocean, the Soviet Union was not at war with Japan before 1945, so some destroyers were transferred to the Northern Fleet.[5]

From the beginning of hostilities, Soviet Naval Aviation provided air support to naval and land operations involving the Soviet Navy. This service was responsible for the operation of shore-based floatplanes, long-range flying boats, catapult-launched and vessel-based planes, and land-based aircraft designated for naval use.

As post-war spoils, the Soviets received several Italian warships and much German naval engineering and architectural documentation.

Cold War

In February 1946 the Red Fleet was renamed the Soviet Navy (Template:Lang-ru),[9] literally the Soviet Military Maritime Fleet. After the war, the Soviets concluded that they needed a navy that could disrupt supply lines, and display a small naval presence to the developing world.[10] As the natural resources the Soviet Union needed were available on the Eurasian land mass, it did not need a navy to protect a large commercial fleet, as the western navies were configured to do.[10] Later, countering seaborne nuclear delivery systems became another significant objective of the navy, and an impetus for expansion.[10]

The Soviet Navy was structured around submarines and small, maneuverable, tactical vessels.[10] The Soviet shipbuilding program kept yards busy constructing submarines based upon World War II German Kriegsmarine designs, which were launched with great frequency during the immediate post-war years. Afterwards, through a combination of indigenous research and technology obtained through espionage from Nazi Germany and the Western nations, the Soviets gradually improved their submarine designs, though they initially lagged the NATO countries by a decade or two.

The Soviets were quick to equip their surface fleet with missiles of various sorts. Indeed, it became a feature of Soviet design to place large missiles onto relatively small, but fast, missile boats, while in the West such an approach would never have been considered tactically feasible. The Soviet Navy did also possess several very large and well-armed guided-missile cruisers, like those of the Kirov and Slava classes. By the 1970s, Soviet submarine technology was in some respects more advanced than in the West, and several of their submarine types were considered superior to their American rivals.[11]

The 5th Operational Squadron (ru:5-я Средиземноморская эскадра кораблей ВМФ)[12] operated in the Mediterranean Sea. The squadron's main function was to prevent largescale naval ingress into the Black Sea, which could bypass the need for any invasion to be over the Eurasian land mass.[10] Flagship of the squadron was for a long period the Sverdlov class cruiser Zhdanov.

Carriers and aviation

Large carriers were not needed to support the naval strategy of disrupting sea lines of communication.[10] Moreover, among the armed services the Navy was lowest in priority in the consideration of the Party's management. Premiers Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev considered aircraft carriers overly expensive, time-consuming, and vulnerable to attack.[citation needed]

The Soviet Navy still had the mission of confronting Western submarines, creating a need for large surface vessels to carry anti-submarine helicopters. During 1968 and 1969 the Moskva-class helicopter carriers were first deployed, succeeded by the first of four aircraft-carrying cruisers of the Kiev class in 1973. Both of these types were capable of operating ASW helicopters, and the Kiev class also operated V/STOL aircraft (e.g., the Yak-38 'Forger'); they were designed to operate for fleet defense, primarily within range of land-based Soviet Naval Aviation aircraft.

During the 1970s the Soviets began Project OREL, whose stated purpose was to create an aircraft carrier capable of basing fixed-wing fighter aircraft in defense of the deployed fleet. The project was canceled during the planning stages when strategic priorities shifted once more. It was during the 1980s that the Soviet Navy acquired its first true aircraft carrier, Tbilisi, subsequently renamed Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union Kuznetsov,[13] which carries Sukhoi Su-33 'Flanker-D' and MiG-29 fighters, and Ka-27 helicopters. A distinctive feature of Soviet aircraft carriers has been their offensive missile armament (as well as long-range anti-aircraft warfare armament), again representing a fleet-defense operational concept, in distinction to the Western emphasis on shore-strike missions from distant deployment. A second carrier (pre-commissioning name Varyag) was under construction when the Soviet Union disintegrated. Construction stopped and the ship was sold, incomplete, to China by Ukraine. It was commissioned into the People's Liberation Army Navy in 2012 as Liaoning.

Soon after the launch of this second Kuznetsov-class ship, the Soviet Navy began the construction of an improved aircraft carrier design, Ulyanovsk, which was to have been slightly larger than the Kuznetsov class and nuclear-powered. The project was terminated, and what little structure had been initiated in the building ways was scrapped.

In part to perform the functions usual to carrier-borne aircraft, the Soviet Navy deployed large numbers of strategic bombers in a maritime role, with the Aviatsiya Voenno-Morskogo Flota (AV-MF, or Naval Aviation service). Strategic bombers like the Tupolev Tu-16 'Badger' and Tu-22M 'Backfire' were deployed with high-speed anti-shipping missiles. The primary role of these aircraft was the interception of NATO supply convoys traveling the sea lines of communication between Europe and North America, and thus countering Operation REFORGER.

Submarines

Due to the USSR's geographic position, submarines were considered the capital ships of the Navy. It was submarines that could penetrate attempts at blockade, either in the constrained waters of the Baltic and Black Seas or in the remote reaches of the USSR's western Arctic. Surface ships were clearly much easier to find and attack. The USSR had entered World War II with more submarines than Germany, but geography and the speed of the German attack precluded it from effectively using its more numerous fleet to its advantage. Because of its opinion that "quantity had a quality of its own" and the insistence of Fleet Admiral Gorshkov, the Soviet Navy continued to operate many first-generation missile submarines, built in the early 1960s, until the end of the Cold War in 1991.

In some respects, including speed and reactor technology, Soviet submarines achieved unique successes, but for most of the era lagged their Western counterparts in overall capability. In addition to their relatively high speeds and great operating depths they were difficult Anti-submarine warfare (ASW) targets to destroy because of their multiple compartments, their large reserve buoyancy, and especially their double-hulled design.[14] Their principal shortcomings were insufficient noise damping (American boats were quieter) and primitive sonar technology. Acoustics was a particularly interesting type of information that the Soviets sought about the West's submarine-production methods, and the long-active John Anthony Walker spy ring may have made a major contribution to their knowledge of such.[14]

The Soviet Navy possessed numerous purpose-built guided missile submarines, such as the Template:Sclass-, as well as many ballistic missile and attack submarines; their Template:Sclass- are the world's largest submarines. The Soviet attack-submarine force was, like the rest of the Navy, designed for interception of NATO convoys, but also targeted American aircraft-carrier battle groups.

Over the years Soviet submarines suffered a number of accidents, most notably on several nuclear boats. The most famous incidents include the Template:Sclass- K-219, and the Template:Sclass- Komsomolets, both lost to fire, and the far more menacing nuclear reactor leak on the Template:Sclass- K-19, narrowly averted by her captain. Inadequate nuclear safety, poor damage control, and quality-control issues during construction (particularly on the earlier submarines) were typical causes of accidents. On several occasions there were alleged collisions with American submarines. None of these, however, has been confirmed officially by the U.S. Navy.

Transition

After the dissolution of the USSR and the end of the Cold War, the Soviet Navy, like other branches of Armed Forces, eventually lost some of its units to former Soviet Republics, and was left without funding.

Inventory

Soviet Navy in 1990:[15]

- 63 ballistic missile submarines

- 6 Typhoon-class submarine

- 40 Delta-class submarine

- 12 Yankee-class submarine

- 5 Hotel-class submarine

- 72 cruise missile submarines

- 6 Oscar-class submarine

- 6 Yankee Notch submarine

- 14 Charlie-class submarine

- 30 Echo-class submarine

- 16 Juliett-class submarine

- 5 Akula-class submarine

- 2 Sierra-class submarine

- 1 Alfa-class submarine

- 46 Victor-class submarine

- 6 November-class submarine

- 3 Yankee SSN submarine

- ≈65 conventional attack submarines

- 18 Kilo-class submarine

- 20 Tango-class submarine

- 25 Foxtrot-class submarine

- 9 auxiliary submarine

- 1 Beluga-class submarine

- 1 Lima-class submarine

- 2 India-class submarine

- 4 Bravo-class submarine

- 1 Losos-class submarine

- 6 aircraft carriers / aviation cruisers

- 4 Kiev-class aircraft carrier

- 2 Moskva-class helicopter carrier

- 30 cruisers

- 3 Slava-class cruiser

- 7 Kara-class cruiser

- 4 Kresta I-class cruiser

- 10 Kresta II-class cruiser

- 4 Kynda-class cruiser

- 2 Sverdlov-class cruiser

- 45 destroyers

- 11 Sovremennyy-class destroyer

- 11 Udaloy-class destroyer

- 18 Kashin-class destroyer

- 3 Kanin-class destroyer

- 2 Kildin-class destroyer

- 113 frigates

- 32 Krivak-class frigate

- 1 Koni-class frigate

- 18 Mirka-class frigate

- 31 Petya-class frigate

- 31 Riga-class frigate

- 35 amphibious warfare ships

- 2 Ivan Rogov-class landing ship

- 19 Ropucha-class landing ship

- 14 Alligator-class landing ship

- 6 Polnocny-class landing ship

- ≈425 patrol boats

Soviet Naval Aviation

The regular Soviet naval aviation units were created in 1918. They participated in the Russian Civil War, cooperating with the ships and the army during the combats at Petrograd, on the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, the Volga, the Kama River, Northern Dvina and on the Lake Onega. The newborn Soviet Naval Air Force consisted of only 76 obsolete hydroplanes. Scanty and technically imperfect, it was mostly used for resupplying the ships and the army.

In the second half of the 1920s, the Naval Aviation order of battle began to grow. It received new reconnaissance hydroplanes, bombers, and fighters. In the mid-1930s, the Soviets created the Naval Air Force in the Baltic Fleet, the Black Sea Fleet and the Soviet Pacific Fleet. The importance of naval aviation had grown significantly by 1938–1940, to become one of the main components of the Soviet Navy. By this time, the Soviets had created formations and units of the torpedo and bomb aviation.

Soviet Naval Infantry

During World War II, about 350,000 soviet sailors fought on land. At the beginning of the war, the navy had only one brigade of marines in the Baltic fleet, but began forming and training other battalions. These eventually were:

- 6 naval infantry regiments (650 marines in two battalions)

- 40 naval infantry brigades of 5–10 battalions, formed from surplus ships' crews. Five brigades were awarded Gvardy (Guards) status.

- Numerous smaller units.

The military situation demanded the deployment of large numbers of marines on land fronts, so the Naval Infantry contributed to the defense of Moscow, Leningrad, Odessa, Sevastopol, Stalingrad, Novorossiysk, Kerch. The Naval Infantry conducted over 114 landings, most of which were carried out by platoons and companies. In general, however, Naval Infantry served as regular infantry, without any amphibious training. They conducted four major operations: two during the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, one during the Caucasus Campaign and one as part of the Landing at Moonsund, in the Baltic. During the war, five brigades and two battalions of naval infantry were awarded Guards status. Nine brigades and six battalions were awarded decorations, and many were given honorary titles. The title Hero of the Soviet Union was bestowed on 122 members of naval infantry units.

The Soviet experience in amphibious warfare in World War II contributed to the development of Soviet combined arms operations. Many members of the Naval Infantry were parachute trained, conducting more drops and successful parachute operations, than the Soviet Airborne Troops (VDV).

The Naval Infantry was disbanded in 1947, with some units being transferred to the Coastal Defence Forces.

In 1961, the Naval Infantry was re-formed and became one of the active combat services of the Navy. Each Fleet was assigned a Marine unit of regiment (and later brigade) size. The Naval Infantry received amphibious versions of standard Armoured fighting vehicle, including tanks used by the Soviet Army.

By 1989, the Naval Infantry numbered 18,000 marines, organized into a Marine Division and 4 independent Marine brigades;

- 55th Marine Division, at Vladivostok

- 63rd Guards Kirkenneskaya Brigade at Pechenga (Northern Fleet)

- 175th Brigade, at Tumanny in the North

- 336th Guards Brigade at Baltiysk (Baltic Fleet)

- 810th Brigade, at Sevastopol (Black Sea Fleet)

By the end of the Cold War, the Soviet Navy had over eighty landing ships, as well as two Ivan Rogov-class landing ships. The latter could transport one infantry battalion with 40 armoured vehicles and their landing craft. (One of the Rogov ships has since been retired.)

At 75 units, the Soviet Union had the world's largest inventory of combat air-cushion assault craft. In addition, many of the 2,500 vessels of the Soviet merchant fleet (Morflot) could off-load weapons and supplies during amphibious landings.

On November 18, 1990, on the eve of the Paris Summit where the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty and the Vienna Document on Confidence and Security-Building Measures (CSBMs) were signed, Soviet data were presented under the so-called initial data exchange. This showed a rather sudden emergence of three so-called coastal defence divisions (including the 3rd at Klaipėda in the Baltic Military District, the 126th in the Odessa Military District and seemingly the 77th Guards Motor Rifle Division with the Northern Fleet), along with three artillery brigades/regiments, subordinate to the Soviet Navy, which had previously been unknown as such to NATO.[16] Much of the equipment, which was commonly understood to be treaty limited (TLE) was declared to be part of the naval infantry. The Soviet argument was that the CFE excluded all naval forces, including its permanently land-based components. The Soviet Government eventually became convinced that its position could not be maintained.

A proclamation of the Soviet government on July 14, 1991, which was later adopted by its successor states, provided that all "treaty-limited equipment" (tanks, artillery and armored vehicles) assigned to naval infantry or coastal defense forces, would count against the total treaty entitlement.

Heads of the Soviet Naval Forces

Commanders of Naval Forces of the RSFSR ("KoMorSi")

- Vasili Mikhailovich Altfater[17] (15 October 1918 – 22 April 1919),

- Yevgeny Andreyevich Berens (24 April 1919 – 5 February 1920),

- Aleksandr Vasiliyevich Nemits (5 February 1920 – 22 November 1921).

Commander-in-Chief's Assistant for Naval Affairs (from 27 August 1921)

Commanders-in-Chief of the Naval Forces of the U.S.S.R. ("NaMorSi") (from 1 January 1924)

- Eduard Samoilovich Pantserzhansky (22 November 1921 – 9 December 1924),

- Vyacheslav Ivanovich Zof (9 December 1924 – 23 August 1926),

- Romuald Adamovich Muklevich (23 August 1926 – 11 June 1931),

- Fleet Flag-officer 1st Rank[18] Vladimir Mitrofanovich Orlov (11 June 1931 – 15 August 1937),

- Fleet Flag-officer 2nd Rank[18] Lev Mikhailovich Galler (10 July – 15 August 1937) Acting,

- Fleet Flag-officer 1st Rank Mikhail Vladimirovich Viktorov (15 August 1937 – 30 December 1937).

People's Commissars for the U.S.S.R. Navy ("NarKom VMF USSR") (from 1938)

- Army Commissar 1st Rank Pyotr Alexandrovich Smirnov (30 December 1937 – 5 November 1938),

- Army Commander 1st Rank Mikhail Petrovich Frinovsky (5 November 1938 – 20 March 1939),

- Admiral[19] Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov (from 27 April 1939).

Commanders-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy ("GlavKom VMF") (from 1943)

- Fleet Admiral Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov (to January 1947),

- Admiral Ivan Stepanovich Yumashev (17 January 1947 – 20 July 1951),

- Fleet Admiral of the Soviet Union Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov (20 July 1951 – 5 January 1956), second term,

- Fleet Admiral of the Soviet Union Sergey Georgyevich Gorshkov (5 January 1956 – 8 December 1985), considered the officer most responsible for reforming the Soviet Navy,

- Fleet Admiral Vladimir Nikolayevich Chernavin (8 December 1985 – December 1991; CIS Navy through August 1992).

See also

- Soviet Naval Aviation

- Soviet Naval Infantry

- Naval history of World War II

- 1966 Soviet submarine global circumnavigation

- List of ships of the Soviet Navy

- List of USSR navy flags

- Morskaya Aviatsiya World War II Soviet Naval Air Service

- List of Russian admirals

References

- ^ https://fas.org/irp/dia/product/smp_84_ch3.htm

- ^ a b Periods of Activities (1926–1941), Online (Accessed 5/24/2008), SOE CDB ME "Rubin", Russia, Saint-Petersburg

- ^ Jürgen Rohwer and Mikhail S. Monakov, Stalin's Ocean-going Fleet: Soviet Naval Strategy and Shipbuilding Programmes, 1935–1953 (Psychology Press, 2001)

- ^ Mark Harrison, "The Volume of Soviet Munitions Output, 1937–1945: A Reevaluation," Journal of Economic History (1990) 50#3 pp. 569–589 at p 582

- ^ a b Sergeĭ Georgievich Gorshkov, Red Star Rising at Sea (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1974)

- ^ Boris V. Sokolov, "The role of lend-lease in Soviet military efforts, 1941–1945," Journal of Slavic Military Studies (1994) 7#3 pp: 567–586.

- ^ Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946

- ^ http://flot.sevastopol.info/ship/lider/tashkent.htm reference

- ^ Красный Флот (Советский Военно-Морской Флот)1943-1955 гг

- ^ a b c d e f Congressional Research Service (October 1976). "Soviet Oceans Development". 94th Congress, 2nd session. U.S. Government Printing Office. 69-315 WASHINGTON : 1976. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ J.E. Moore, "The Modern Soviet Navy", in: Soviet War Power, ed. R. Bonds (Corgi 1982)

- ^ Michael Holm, 5th Operational Squadron, accessed 16 February 2012

- ^ "The Self-Designing High-Reliability Organization: Aircraft Carrier Flight Operations at Sea." Rochlin, G. I.; La Porte, T. R.; Roberts, K. H. Footnote 39. Naval War College Review. Autumn, 1987, Vol. LI, No. 3.

- ^ a b Norman Polmar, Guide to the Soviet Navy, Fourth Edition (1986), United States Naval Institute, Annapolis Maryland, ISBN 0-87021-240-0

- ^ "Soviet Navy Ships - 1945-1990 - Cold War". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ IISS Military Balance 1991–1992, p.30–31

- ^ Military ranks were abolished in 1918–1935.

- ^ Fleet Flag-officer 2nd Rank from 17 January 1938, Admiral (June 1940), Admiral of the Fleet (February 1944), Rear Admiral (1948), Admiral of the Fleet (1953), Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union (March 1955), Vice-Admiral (February 1956), Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union (1988, posthumous).

Bibliography

- Goldstein, Lyle; Zhukov, Yuri (2004). "A Tale of Two Fleets: A Russian Perspective on the 1973 Naval Standoff in the Mediterranean". Naval War College Review.

- Goldstein, Lyle; John Hattendorf; Zhukov, Yuri. (2005) "The Cold War at Sea: An International Appraisal". Journal of Strategic Studies. ISSN 0140-2390

- Gorshkov, Sergeĭ Georgievich. Red Star Rising at Sea (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1974)

- Nilsen, Thomas; Kudrik, Igor; Nikitin, Aleksandr (1996). Report 2: 1996: The Russian Northern Fleet. Oslo/St. Petersburg: Bellona Foundation. ISBN 82-993138-5-6. Chapter 8, "Nuclear submarine accidents".

- Oberg, James (1988). Uncovering Soviet Disasters. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 0-394-56095-7.

- Rohwer, Jürgen, and Mikhail S. Monakov, Stalin's Ocean-Going Fleet: Soviet Naval Strategy and Shipbuilding Programmes, 1935–1953 (Psychology Press, 2001)

- Sontag, Sherry; Drew, Christopher; Drew, Annette Lawrence (1998). Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage. Harper. ISBN 0-06-103004-X.

External links

- Russian Navy

- Globalsecurity.org page on the Soviet Navy.

- Admiral Gorshkov and the Soviet Navy

- Soviet Submarines

- Red Fleet

- Flags & Streamers

- Warship Listing

- Russian Navy Weapons

- All Soviet Warships – Complete Ship List (English)

- All Soviet Submarines – Complete Ship List (English)

- Understanding Soviet naval developments (English)