Talk:Human microbiome/Archive 1

| This is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 |

Title change to "Human microbiome"

It appears the name of this article has changed over time, and some are not happy with the current title of "human flora" because it excludes all the animals within us. The term "human microbiome" appears to be more accurate and gaining in usage. Here's a recent NYT article on the subject: How Microbes Defend and Define Us. (It uses simply "microbiome," but that refers to any community of microorganisms. "Human microbiome" is more precise and incorporated in the name of the Human Microbiome Project.) I suggest we change the title to "Human microbiome." Frappyjohn (talk) 01:54, 9 November 2010 (UTC)

I agree about changing the name of the article. Since bacteria is not a plant, it is just non-sense calling it by micro flora or even flora. Then it is plausible changing it to Human Microbiome (or microbiota) — Preceding unsigned comment added by Gustavo.leite (talk • contribs) 04:34, 26 February 2011 (UTC)

A title change, please.I am totally pro "Human microbiome" too. Flora is okay, but taxonomically old fashioned. The term "biome" appropriately emphasizes the ecological nature of current research in this area, plus we can refer to the Human Microbiome Project, which is organizing the research. Plus, I want mites and any other animals here, too. They belong here; I came here specifically to read about them. A search for "human flora" can bounce here. Eperotao (talk) 00:02, 10 April 2011 (UTC)

Per the above, I have renamed (i.e. moved) the article from "Human flora" to "Human microbiome." I did a quick cleanup of the lead paragraph (but did I err in equating "microbiome" with microbiota"?). The second paragraph seems to stand as is as an explanation of why "microflora" is a misnomer. The rest of the article probably needs cleanup. I see its subheads all use "flora," for example. Frappyjohn (talk) 04:33, 12 April 2011 (UTC)

The introduction needs a serious edit here. The 10:1 ratio was based on using numbers from very crude estimates never intended to be widely used and never seriously quantified. It looks to me that there is an edit that really doesn't get that point across and still leaves that poor 10:1 estimate front and center. I am going to attempt to edit this. This article explains it very well, http://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/en/11-is-new-estimated-ratio-of-bacterial-to-human-cells/ and because every link I've saved from the site is already broken in just a couple months,

"Recently, three scientists from Israel and Canada took it upon themselves to critically examine where this estimate came from and whether it holds true.

In a paper published in BioRxiv, Sender, et al. showed both the numerator and the denominator of the 10:1 ratio appeared to be based on crude assessments from decades ago. They traced the origin of the numbers back to a 1972 journal article by Thomas D. Luckey, who performed what they called a “back of the envelope estimate” that was never intended to be quoted widely.

Usual estimations of bacterial cells in the body range from 1014 or 1015, assuming a “reference man” of between 20 and 30 years of age who is 170 cm tall and weighs 70 kg; measured concentrations of bacteria (that is, bacteria per gram) are then multiplied by the volume of each organ.

The main problem with the estimation method was that it assumed a constant bacterial density throughout the digestive tract. Now we know most of the microbes in the digestive tract are concentrated in the colon. By incorporating this and other more recent information, authors came up with 3.9×1013 as the new estimate of bacteria in a standard adult male." — Preceding unsigned comment added by Dwot (talk • contribs) 13:46, 25 February 2016 (UTC)

Small change

I changed the location to where the link "lowered immunity" was pointing. Before it was an non-excisting article and I changed it to "Immune System". If you feel that the change was for the worst please feel free to change it back.

good/ bad

there is good and bad bacteria! what happens when you dont have the good bacteria and what should you do about it and what are or if any symptoms?

- You can survive, but you may not digest food as well or get as much nutrition out of your food. "Bad" bacteria may take the opportunity to grow too much in your intestines. You may get diarrhea and feel sick. See a doctor if you think this is happening to you. There are supplements called probiotics that can replace the "good" bacteria in your gut. See the page on gut flora that has a lot more info on this. delldot | talk 20:10, 15 November 2005 (UTC)

Most?

The first line of the article says that most of the bacteria in/on the body perform "tasks that are useful or even essential to human survival". Can anyone verify this or cite a source? I wonder if I should maybe tag it with {{Fact}}? Thanks, delldot | talk 20:10, 15 November 2005 (UTC)

Question on immune system and normal flora

I was curious why the body's immune system doesn't attack the normal flora and came here to try to find that. Could someone explain (and add to the article?) why this is the case? Thanks.

- Well, none of those bugs are invasive. They don't destroy the gut wall and are therefore not tagged as "harmful" by the immune system. I'm not sure if this is the right page to discuss this phenomenon - it's a list. JFW | T@lk 20:56, 16 November 2005 (UTC)

Normal flora is (generally) not pathogenic. There's no need to defend against them, so the body doesn't. We have a commensal relationship, such as breaking down food. Not mentioned in the article, because our skin is COVERED with bacteria, we have a living shield against many bacteria that may be pathogenic; normal flora protects us against other bacteria (or often fungi). We have simply learned that it is best not to kill our tiny friends. Eedo Bee 14:56, 19 August 2007 (UTC)

Numbers wrong?

This article and the article on Gut Flora disagree on the (1) the number of human cells in the body and (2) the number of bacteria. This kind of disagreemtn is what frightens me about the Wikipedia. Can someone with the knowledge please correct. Goaty 02:46, 7 December 2005 (UTC)

- This article was most likely wrong as it contradicts its source. I wonder what AxelBoldt was thinking by making the change without even explaining the edit. Put 1013 for the amount of cells and 1014 for the amount of bacteria back where they supposedly belong. 202.162.85.116 00:41, 22 February 2006 (UTC)

There should definitely be some sort of citation for those numbers of scale comparison (bacterial cell numbers vs. somatic cell numbers). I have read estimates of 10 trillion body cells in the average adult. 10,000,000,000,000 (1013) --Frenkmelk 01:56, 7 December 2006 (UTC)

Some numbers in the section "Culturable and nonculturable bacteria" are confusing. The number of bacteria is given as 4 quadrillion, which is 4*10**15. The number of bacterial cells is given as 10**14. Please revise. --Rickhev1 (talk) 20:03, 15 December 2009 (UTC)

The numbers are still inconsistent: 10 trillion cells is mentioned here (no citation), 100 trillion is mentioned in Gut flora (no citation), and "between 50 and 75 trillion cells" is the statement in List of distinct cell types in the adult human body (you guessed it, no citation). 199.46.198.232 (talk) 19:20, 1 November 2010 (UTC)

These articles might be useful for this page: PMID 16033867, PMID 17183309, and PMID 17183312. Ninjatacoshell 19:26, 31 May 2007 (UTC)

Name Change

The title "Bacteria in the human body" in lieu of "Normal Flora" is misleading, as not all normal flora is bacterial, just microbial. We have non-pathogenic levels of fungi and sometimes parasitic animals (nematodes) that are considered "Normal Flora". Appreciation of the basic differences between the Domains of life is a must. Eedo Bee 15:01, 19 August 2007 (UTC)

I would ask that a moderator change the name, this issue was posed a considerably long time ago (relatively). Normal Flora is the appropriate name. Eedo Bee 13:31, 27 August 2007 (UTC)

Scientific research into the role of bacteria and Hunger

I don't have access to specific documents, just a hyper link to title and information numbers... Dynamics of intragastric bacteria plexus in early morning hunger. If someone who could use this url to find information that might be suitable to inclusion on this page, it might be interesting. the url is from a japanese researcher..just a thought though. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Kesuki (talk • contribs) 21:56, 13 March 2008 (UTC)

NAP book: Microbial Evolution and Co-Adaptation

Freely-available book on this topic released from the National Academies: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12586#description II | (t - c) 17:30, 21 April 2009 (UTC)

some recent scientific papers

I don't have time now, but here are some recent refs, freely available as pdfs on the internet,that cover the topic of microflora in the skin and nose

Grice et al Science 29 may 2009 page 1190 Grice et al Genome Research 2008 page 1043 Dowd et al BMC Microbiology 6 march 2008 Gao et al Proceedings US national academy sciences Feb 20,2007 page 2927

Jousimies-somer et al Journal Clinical Microbiology dec 1989, page 2736

Larson et al Journal Clinical Microbiology, march 1986 page 604

one point these papers make is that different parts of the human skin are very different; to quote the grice 2009 paper "The skin is also an ecosystem, harboring [microbes] that live in a range of ...distinct niches. For example,hairy moist underarms lie a short distance from smooth dry forearms, but these two niches are likely as ..dissamilar as rainforest are to deserts"Cinnamon colbert (talk) 13:51, 21 July 2009 (UTC)

intro

I think most scientists view the human microflora as consisting of "permament" residients - bacteria consistiently found, and transients, which can make up a lot of the total bacteriaCinnamon colbert (talk) 15:50, 23 July 2009 (UTC)File:Bold text--117.96.1.61 (talk) 07:26, 21 October 2010 (UTC)

Regards

--117.96.1.61 (talk) 07:26, 21 October 2010 (UTC)Baliram singh

unit = %

"Range of Incidence" should read "Range of Incidence / %" to name the used unit. I do this edit. Helps non-native speakers as me. --Helium4 (talk) 06:27, 13 January 2012 (UTC)

Merger from Bacterial flora

I propose that the article Bacterial flora should be merged into this article. Both articles cover the same subject, the human body flora. Having two articles on seems redundant to me. I believe that both articles contain information the other one could benefit from, however in my opinion the article Human microbiome is more extensive and cites more reliable sources. Nevertheless I believe there is a lot of content in Bacterial flora that this article could benefit from. --Shinryuu (talk) 01:36, 26 November 2012 (UTC)

The content of Bacterial flora belongs rightly to the subject covered here in Human microbiome, then Bacterial flora could redirect to Flora (microbiology) or be given its own page. Drlectin (talk) 13:50, 10 January 2013 (UTC)

- I concur, and I support the merger. — James Estevez (talk) 21:31, 20 April 2013 (UTC)

- Support. I agree that the bacterial flora should be merged into this article, as this article is slightly broader in that it covers archaea and fungal flora as well. Ashleyleia (talk) 18:21, 21 April 2013 (UTC)

- Support. I agree that the content specific to the Human microbiome should be transferred here, but I believe the two pages should remain separate, as the two terms are not synonymous. I would, however, then support the merge/redirect of the remaining material at Bacterial flora to Flora (microbiology). AdventurousSquirrel (talk) 02:28, 16 May 2013 (UTC)

- Seemed like everyone was more or less on the same page, so I was bold and went ahead with the changes. Please let me know if you see any issues. AdventurousSquirrel (talk) 03:45, 16 May 2013 (UTC)

Introduction - is misleading at best or more likely wrong

First line as of Aug 17/2013: "The human microbiome (or human microbiota) is the aggregate of microorganisms, a microbiome that resides on the surface and in deep layers of skin, in the saliva and oral mucosa, in the conjunctiva, and in the gastrointestinal tracts." This is wrong. The article itself goes on to talk about vaginal organisms. I also think it would be helpful to enumerate the types of bugs found, rather than repeating the same word in a single sentence as if that is going to help!! (microbiome). Obviously, somebody needs to EDIT this. Archea, Bacteria, Fungi (including yeast) are mentioned later, but how about viruses and algae (which I have read ARE part of our microbiome) and protozoa (which I have no knowledge of, yea or nay)? Multicellular or only single celled? rotifers? IDK. This article also fails full disclosure of the true meagerness of what we know (observed) compared to what is unknown. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence and so, last I heard, for the most part we can not be confident where none exist. The brain, in our lungs, ears, eyes, nose, blood, nerves, urethra, vagina, etc. etc.?? I mention some of these even though I KNOW they are inhabited because the introduction implies a very limited number of habitats. I think this is grossly misleading. I also think the differentiation between a (micro) parasite and "normal flora" (and is a pathogen a parasite?) is unnecessary and confusing. (Not to mention differences between symbiotic vs commensal microorganisms.) Wouldn't, say, the TB bacteria be part of a CARRIER'S "normal flora" but using the arbitrary definition here NOT be part of it for a person with symptomatic TB? (Is there really a unambiguous meaning of "normal flora"?) How can you exclude pathogens and parasites? (I understand that the original title was something about flora, but so what?) Bottom line; this needs: 1. Improved, more general definition of where these critters are known to exist, and where they are KNOWN not to exist, with mention that the rest of body is a great unknown. 2. Improved definition of what types of organisms are included. 3. Explanation of parasites, pathogens, symbiotes, and commensal organisms in the context of this article on the human microbiome. Together with the rationale (if there is one) in separating out hostile species. What about enemies of our enemies...are they necessarily our friends? Context.173.189.75.50 (talk) 20:52, 17 August 2013 (UTC)

Commensalism or mutualism?

I'm wondering about describing (the various carbohydrate-digesting) gut bacteria as "commensal.” (Paragraph #5 under the Bacteria subtitle: "Many of the bacteria in the digestive tract, collectively referred to as the gut flora, are able to break down certain nutrients such as carbohydrates that humans otherwise could not digest. The majority of these commensal bacteria….") Since the bacteria also benefit by having a warm, nutrient rich environment, wouldn’t the relationship be defined as mutualism? ---- — Preceding unsigned comment added by Dfirak (talk • contribs) 04:13, 13 November 2013 (UTC)

Link broken: Respiratory flora

Changed link to "Lung microbiome" ("Respiratory flora" was broken) feel free to reverse/delete altogether if not strictly correct, this could also need a reference to nasal microbiome too. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 134.211.129.121 (talk) 06:16, 19 June 2014 (UTC)

Move discussion in progress

There is a move discussion in progress on Talk:Microbiota (disambiguation) which affects this page. Please participate on that page and not in this talk page section. Thank you. —RMCD bot 20:15, 27 January 2015 (UTC)

Section on Demodex mites

This section and the associated microphotograph are at odds with the qualification in the definition/introduction that "[m]icro-animals which live on the human body are excluded" from microbiota. Seems like either the former should be removed or if appropriate the latter altered, I am not familiar enough with the consensus use of this term to know which. 146.129.38.53 (talk) 18:49, 26 June 2015 (UTC)

I'm going to be bold and remove the referenced section so the content reflects the definition given in the introduction, if anyone thinks this is premature feel free to revert and potentially edit the intro. 146.129.38.53 (talk) 19:47, 26 June 2015 (UTC)

Prokaryotes

There's >2700 species in humans. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00293-5 JFW | T@lk 12:10, 7 October 2015 (UTC)

External links modified

Hello fellow Wikipedians,

I have just added archive links to one external link on Human microbiota. Please take a moment to review my edit. If necessary, add {{cbignore}} after the link to keep me from modifying it. Alternatively, you can add {{nobots|deny=InternetArchiveBot}} to keep me off the page altogether. I made the following changes:

- Added archive https://web.archive.org/20051128011443/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/books/bv.fcgi?rid=mmed.chapter.500 to http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=mmed.chapter.500

When you have finished reviewing my changes, please set the checked parameter below to true to let others know.

This message was posted before February 2018. After February 2018, "External links modified" talk page sections are no longer generated or monitored by InternetArchiveBot. No special action is required regarding these talk page notices, other than regular verification using the archive tool instructions below. Editors have permission to delete these "External links modified" talk page sections if they want to de-clutter talk pages, but see the RfC before doing mass systematic removals. This message is updated dynamically through the template {{source check}} (last update: 18 January 2022).

- If you have discovered URLs which were erroneously considered dead by the bot, you can report them with this tool.

- If you found an error with any archives or the URLs themselves, you can fix them with this tool.

Cheers. —cyberbot IITalk to my owner:Online 07:14, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

Ordering content

Per discussion here I merged content that grew up in the Microbiota article into this article. After blending, I will update the lead of this article and copy it to that section, with a link to this main article, per WP:SYNC. Jytdog (talk) 20:12, 18 June 2016 (UTC)

While working on that, it is has become clear that we have the same problem here with content related to Gut flora, where a bunch of content has been entered here that is not there. Before I can finish the above, I need to merge the gut flora content here into that article, and bring the lead of that article here. Jytdog (talk) 20:21, 18 June 2016 (UTC)

Content not supported by the source

The following was added somewhere in this set of edits. It is contradicted by the source.

- Uterus

The uterus has been found to possess its own characteristic microbiome that differs significantly from the vaginal microbiome. Microbiota in the uterus has been identified as having an effect on pregnancy outcomes. Specific bacteria are associated with a successful birth while others, while not causing signs or symptoms, are associated with a negative outcome.[1]

References

This source in the section about the uterus talks about one clinical study of 33 women undergoing ART, which is too small to generalize from, but what it says is "There were 278 genus calls present across patient samples. In both patients who became pregnant and those that did not, Lactobacillus and Flavobacterium represented the most common species. Moreover, the diversity indices between the two groups were high but appeared to be similar. After multiple test corrections, there were no associations large enough between specific bacteria and outcomes. However, in this pilot study the sample size was small, and differences may be seen with larger numbers in future studies." In other words, the opposite of the content above. Jytdog (talk) 12:09, 25 June 2016 (UTC)

- The information on the number of genera found in the uterus was the only piece of information I used in the this article from that particular small study.

- The sentence I wrote: "Specific bacteria are associated with a successful birth while others, while not causing signs or symptoms, are associated with a negative outcome" is based on other statements later by Franasiak, et.al in the review article where they state:

"... [Pregnancy O]utcomes improved when Lactobacilli were present. This is sharp contrast to other species such as Propionibacterium and Actinomyces among others, where impaired clinical outcomes were documented."

- These sentences about outcomes appear later in the article in two paragraphs before the section 'Male Reproductive Tract Microbiome' and after the section you quote above.

- The article is, admittedly a combination of bacteriology (refs not required to be MEDRS), and clinical content (MEDRS). The information on the number of genera is adequately sourced. The content about the pregnancy outcomes is MEDRS sourced.

- Courtesy and civility suggest that the blanking of content be discussed on the talk page before the content and references are removed. A lot of content disappeared over the minor issue you raised which could have amicably solved between two editors, in good faith, who want to see an improved encyclopedia. Would you be so kind to rollback your own content deletion? Best Regards,

- Barbara (WVS) (talk) 23:18, 25 June 2016 (UTC)

- The sentence quoted is from the section of that article discussing the ovarian follicle microbiome, not the uterus. The content added to the article made claims about pregnancy outcomes which is biomedical information and MEDRS applies.Jytdog (talk) 00:07, 26 June 2016 (UTC)

- I've gone ahead and added content here, and to endometrium based on that ref. I an not sure this should be called "uterus" but i left it that way. Jytdog (talk) 04:01, 26 June 2016 (UTC)

Like and thank you. Best Regards, Barbara (WVS) (talk) 00:40, 27 June 2016 (UTC)

Like and thank you. Best Regards, Barbara (WVS) (talk) 00:40, 27 June 2016 (UTC)

- Barbara (WVS) (talk) 23:18, 25 June 2016 (UTC)

uterus sub section

[1] might be good to add to above sub section (I have access to full article if needed)--Ozzie10aaaa (talk) 22:29, 27 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thank you for your suggested source. I can get on with adding content and references and have some peace. Best Regards,Barbara (WVS) (talk) 03:42, 1 July 2016 (UTC)

- I think I know what you mean--Ozzie10aaaa (talk) 11:34, 11 July 2016 (UTC)

necrobiome

User:Thenhl15 about the content you added here and restored with no edit note here. As noted, please use reviews published in the biomedical literature, not primary sources (papers where the actual experiments are described) and popular media. See WP:MEDDEF. We also don't name who did what (because we don't use primary sources and report various papers - we transmit accepted knowledge as found in reviews) Jytdog (talk) 12:55, 7 June 2017 (UTC)

Microbial metabolism diagram and metabolite table

This review's coverage of microbiota-derived metabolite biosynthesis/pharmacodynamics is pretty comprehensive.[1] PMID 26531326 seems to cover the same topic - need to get access to it. Seppi333 (Insert 2¢) 08:59, 27 June 2016 (UTC)

- here Barbara (WVS) (talk) 08:59, 28 June 2016 (UTC)

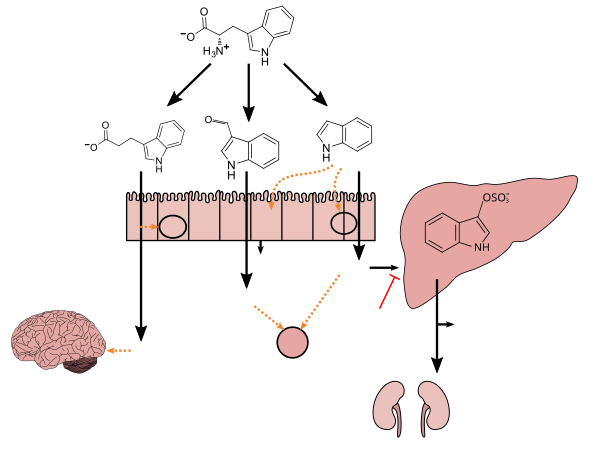

Metabolism diagram

Tryptophan metabolism by human gastrointestinal microbiota ()

|

The File:Microbiota-derived_3-Indolepropionic_acid.jpg diagram was recently recreated as an svg image with annotated wikitext (i.e., the diagram shown in this section). Does anyone have any feedback/suggestions for revision? Seppi333 (Insert 2¢) 00:23, 4 November 2017 (UTC)

Section references

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zhang LS, Davies SS (April 2016). "Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions". Genome Med. 8 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x. PMC 4840492. PMID 27102537.

Lactobacillus spp. convert tryptophan to indole-3-aldehyde (I3A) through unidentified enzymes [125]. Clostridium sporogenes convert tryptophan to IPA [6], likely via a tryptophan deaminase. ... IPA also potently scavenges hydroxyl radicals

Table 2: Microbial metabolites: their synthesis, mechanisms of action, and effects on health and disease

Figure 1: Molecular mechanisms of action of indole and its metabolites on host physiology and disease - ^ Wikoff WR, Anfora AT, Liu J, Schultz PG, Lesley SA, Peters EC, Siuzdak G (March 2009). "Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (10): 3698–3703. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3698W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812874106. PMC 2656143. PMID 19234110.

Production of IPA was shown to be completely dependent on the presence of gut microflora and could be established by colonization with the bacterium Clostridium sporogenes.

IPA metabolism diagram - ^ "3-Indolepropionic acid". Human Metabolome Database. University of Alberta. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Omar RA, Chain DG, Frangione B, Ghiso J, Pappolla MA (July 1999). "Potent neuroprotective properties against the Alzheimer beta-amyloid by an endogenous melatonin-related indole structure, indole-3-propionic acid". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (31): 21937–21942. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.31.21937. PMID 10419516. S2CID 6630247.

[Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA)] has previously been identified in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of humans, but its functions are not known. ... In kinetic competition experiments using free radical-trapping agents, the capacity of IPA to scavenge hydroxyl radicals exceeded that of melatonin, an indoleamine considered to be the most potent naturally occurring scavenger of free radicals. In contrast with other antioxidants, IPA was not converted to reactive intermediates with pro-oxidant activity.

Metabolite table

• named ref citations used in the table above that are currently included in the article lead or the diagram.[1][8][13][14]

Reflist

|

|---|

|

References

|

External links modified

Hello fellow Wikipedians,

I have just modified one external link on Human microbiota. Please take a moment to review my edit. If you have any questions, or need the bot to ignore the links, or the page altogether, please visit this simple FaQ for additional information. I made the following changes:

- Added archive https://web.archive.org/web/20131016102359/http://www.usc.edu/hsc/pharmacy/pd_labs/COPM11-00.pdf to http://www.usc.edu/hsc/pharmacy/pd_labs/COPM11-00.pdf

When you have finished reviewing my changes, you may follow the instructions on the template below to fix any issues with the URLs.

This message was posted before February 2018. After February 2018, "External links modified" talk page sections are no longer generated or monitored by InternetArchiveBot. No special action is required regarding these talk page notices, other than regular verification using the archive tool instructions below. Editors have permission to delete these "External links modified" talk page sections if they want to de-clutter talk pages, but see the RfC before doing mass systematic removals. This message is updated dynamically through the template {{source check}} (last update: 18 January 2022).

- If you have discovered URLs which were erroneously considered dead by the bot, you can report them with this tool.

- If you found an error with any archives or the URLs themselves, you can fix them with this tool.

Cheers.—InternetArchiveBot (Report bug) 01:35, 12 January 2018 (UTC)

urinary

if anybody cannot access the 2 reviews i added the urinary tract section, i will be happy to send them. Jytdog (talk) 23:32, 15 July 2018 (UTC)

- and my apologies for this edit note. too harsh. but really. the two refs were added the end of the paragraph, meaning they both support everything in the paragraph. am fine with them being on every sentence. Jytdog (talk) 23:36, 15 July 2018 (UTC)

- This statement is curious, seems unnecessary, and not supported by either reference, imo: "anaerobic bacteria would not grow in the conditions commonly used in cultures." Common culture methods for anaerobic bacteria: PMID 19768627; PMID 27028132; 2015 review. We can delete the statement or use these more specific refs. --Zefr (talk) 23:53, 15 July 2018 (UTC)

- @Jytdog: See below.

PMID 28753805 →http://sci-hub.tw/10.1016/j.euf.2016.11.001

PMID 28444712 →http://sci-hub.tw/10.1002/nau.23006

Seppi333 (Insert 2¢) 03:36, 17 July 2018 (UTC)

- PMID 28753805

Moreover, the bladder and urine have long been considered sterile in healthy individuals because of technical difficulties in characterizing the full spectrum of urinary bacterial species using standard microbiological methods. Advances in molecular biology techniques and culture methods have allowed definition of a specific microbiome associated with several body sites previously believed to be sterile, including the urinary tract

andTraditionally, the study of urinary bacterial communities mainly included standard urine cultures, which had significant limitations for detection of the full spectrum of urinary bacterial species (slow-growing bacteria that die in the presence of oxygen). Advances in new approaches such as 16S rRNA sequencing and enhanced or expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) have led to rapid progress in UM knowledge

- PMID

Conventionally, urine is considered to be sterile, illustrated by the frequent absence of bacterial growth when urine is cultured from asymptomatic individuals and in the diagnostic setting. However, key studies using new techniques have found bacterial identifiers within voided urine which is apparently sterile when subjected to conventional laboratory culture, taken from patients with no associated symptoms of infection

- PMID

- PMID 28753805

- Yes I slapped that in to the page the stop the foolish edit war over badly sourced content. Yes it can be improved. Jytdog (talk) 13:58, 17 July 2018 (UTC)

- which I just did adding two words so it now reads "standard clinical microbiological culture methods to detect bacteria in urine when people show signs of a urinary tract infection". Jytdog (talk) 14:00, 17 July 2018 (UTC)

- The reason why it is useful, perhaps even necessary, is to address the common conception that urine is sterile. Jytdog (talk) 14:05, 17 July 2018 (UTC)

Mass of all the bacteria in one's body

It gives the numerical comparison but what's the estimated weight of all the bacteria in one's body, and what proportion would it be to the mass of one's cells? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 50.101.119.176 (talk) 21:31, 7 April 2019 (UTC)

Time to update this page?

I would like to suggest that it is time to revise and update the Human Microbiota page. Of the 88 references there seem to be only 22 that are later than 2014, although most of the literature has been published since then. PubMed lists 48,073 items of ‘Human Microbiota’ of which 35,957 items are from the last 5 years. Thus 75% of published literature on the topic is less than 5 years old while only 25% of the WP page is so new.

Specifically I think the page could be updated with the following changes:

1. The page should refer to the Microbiota page – that page gives an overview of the various microbiota, of which Human is just one type.

2. Section 2 should be renamed as “Study methods” or “Techniques”. Most of Section 2 could probably be eliminated, since the same information is presented in the Microbiota page.

3. The Human Microbiome Project is cited appropriately, but has been completed and so could be summarized in the past tense. It has its own page, which should be referenced.

4. The description of bacterial Tryptophan metabolism is quite extensive but no other pathways and metabolites are reviewed. How relevant is it? Should it be cut or should all possible pathways be reviewed as well?

5. Section 6 should include at least a mention and a citation for each of the conditions that have been associated with changes in the balance of organisms in the microbiota. These should include vaginosis, obesity, diabetes (Types -1 and -2), autism, C. diff infection. Obviously there should be an appropriate allocation of space for each condition – some have a well-established connection to the microflora and others are rather speculative.

6. There should be a new section on current efforts to modify human health by changing the microbiota. Probiotic food supplements and fecal transplants should be covered.

7. Sections 7 and 8 seem very minor and could be removed.

8. References to reviews that are over 5 years old could be considered for removal.

Does anyone have any comments on this?

Ed Shillitoe (talk) 15:20, 3 July 2019 (UTC)

@E.Shillitoe:, all of these seem reasonable to me. Do you want to try boldly making some edits? If you need specific advice, let me know. But also this article should be kept pretty high-level - we like to use WP:SUMMARY style and there's articles like human gastrointestinal microbiota for more details. II | (t - c) 23:54, 12 July 2019 (UTC)

Relative numbers section

As I understand it, the previous figure of 100 trillion cells was in reference to microbes, not bacteria, which means it would have included fungi and viruses and such. Am I mistaken, or are these two reports not even talking about the same subsets of cells? Krychek (talk) 21:00, 4 September 2018 (UTC)

- I do not know whether it referred to microbes in total; even then it seems high. But anyway, what I personally remember is that in local universities, the teachers happily picked up the 10:1 reference. Only in the microbial ecology department have there been comments that the number 10:1 is too high. The article acknowledges this via "more recent estimates have lowered that ratio to 3:1 or even to approximately the same number", but I would also include lower numbers such as 1:1.3, and, most importantly, actually add more links to papers that discuss the number. Either way, I think we need to focus on simple fatual numbers. IF we compare to the number of BACTERIA, then only bacteria should be compared, and here I think the number is closer to e. g. 1.3 or 2.0, than 3.0 or even 10.0. Note that I do not really recall that it was to microbes; I always thought it referred to bacteria primarily. 2A02:8388:1641:8380:3AD5:47FF:FE18:CC7F (talk) 12:14, 17 September 2019 (UTC)

The statements about total microbe counts require better sourcing

News articles don't suffice for biomedical content sourcing. The sole medical source for that statement is a primary source, which, per WP:MEDRS, should not be used to contradict assertions about microbe counts from review articles (e.g., [2] states 100 trillion). Seppi333 (Insert 2¢) 04:08, 21 February 2020 (UTC)

- Seppi333 this resource is a review in Nature and would seem to suffice. (Altmäe, S., Franasiak, J.M. & Mändar, R. The seminal microbiome in health and disease. Nat Rev Urol 16, 703–721 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-019-0250-y) Should I make the change? AshLin (talk) 03:15, 28 March 2020 (UTC)

Remove the 10:1 myth from the article

Repeating myths even when cushioned in a negative will cause some skim readers to take away the myth rather than the truth. So, don't discuss the 10:1 myth at length in the Relative numbers section. Just remove and replace by what we now know is closer to the truth: human to bacteria at around 1:1 with bacteria contributing no significant amount of weight because the cells are tiny (200g for 70kg human). See Sender 2016 PLoS Biology. — J.S.talk 16:30, 14 January 2021 (UTC)

Genetic modification of bacteria, ... in gastrointestinal tract

Can the human microbiome (gastrointestinal tract) be genetically modified to destroy microplastics that have been consumed ? Might be possible I think as other organisms also have mechanisms to break down (certain) plastics, see Plastisphere#Degradation_by_organisms. This could then benefit health as the microplastics no longer linger in the body (and microplastics can trigger certain cancers). Perhaps info on that can be added to article. --Genetics4good (talk) 08:34, 27 February 2021 (UTC)

Add a reference or bibliography

A reference or bibliography for ‘turtles all the way down’, by John Green for this article being quoted many times. I would try and do this although this is my first time and I would not like to mess up on an important article. Megabits13 (talk) 20:56, 16 January 2022 (UTC)Megabits13