Ted Bundy

Ted Bundy | |

|---|---|

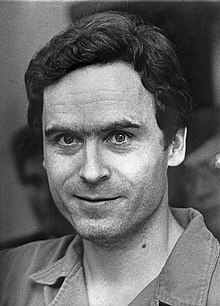

Bundy in July 1978 | |

| Born | Theodore Robert Cowell November 24, 1946 Burlington, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | January 24, 1989 (aged 42) |

| Cause of death | Execution by electrocution[2] |

| Resting place | Body cremated in Gainesville, Florida; ashes scattered at an undisclosed location at Cascade Range, Washington. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Carole Ann Boone

(m. 1980–1986) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parents |

|

| Conviction(s) | |

| Criminal penalty | Death by electrocution |

| Escaped |

|

| Details | |

| Victims | 30 confessed; total unconfirmed |

Span of crimes | February 1, 1974Template:G has been used for the following templates in the past:

|

| Country | United States |

| State(s) |

|

Date apprehended | August 16, 1975 |

Theodore Robert Bundy (né Cowell; November 24, 1946 – January 24, 1989) was an American serial killer who kidnapped, raped, and murdered numerous young women and girls during the 1970s and possibly earlier. After more than a decade of denials, before his execution in 1989 he confessed to 30 homicides that he committed in seven states between 1974 and 1978. The true number of victims is unknown and possibly higher.

Bundy was regarded as handsome and charismatic, traits that he exploited to win the trust of victims and society. He would typically approach his victims in public places, feigning injury or disability, or impersonating an authority figure, before knocking them unconscious and taking them to secluded locations to rape and strangle them. He sometimes revisited his secondary crime scenes, grooming and performing sexual acts with the decomposing corpses until putrefaction and destruction by wild animals made any further interactions impossible. He decapitated at least 12 victims and kept some of the severed heads as mementos in his apartment.[3] On a few occasions, he broke into dwellings at night and bludgeoned his victims as they slept.

In 1975, Bundy was jailed for the first time when he was incarcerated in Utah for aggravated kidnapping and attempted criminal assault. He then became a suspect in a progressively longer list of unsolved homicides in several states. Facing murder charges in Colorado, he engineered two dramatic escapes and committed further assaults in Florida, including three murders, before his ultimate recapture in 1978. For the Florida homicides, he received three death sentences in two separate trials. Bundy was executed in the electric chair at Florida State Prison in Raiford, Florida on January 24, 1989.[4]

Biographer Ann Rule, who had previously worked with Bundy, described him as "a sadistic sociopath who took pleasure from another human's pain and the control he had over his victims, to the point of death, and even after."[5] He once called himself "the most cold-hearted son of a bitch you'll ever meet."[6][7] Attorney Polly Nelson, a member of his last defense team, wrote he was "the very definition of heartless evil."[8]

Early life

Childhood

Ted Bundy was born Theodore Robert Cowell on November 24, 1946, to Eleanor Louise Cowell (1924–2012; known as Louise) at the Elizabeth Lund Home for Unwed Mothers[9] in Burlington, Vermont. His father's identity has never been confirmed. His birth certificate is said to assign paternity to a salesman and Air Force veteran named Lloyd Marshall,[10] though other accounts state his father is listed as "Unknown".[11] Louise claimed she had been seduced by an old money war veteran named Jack Worthington,[12] and the King County Sheriff's Office has him listed as the father in their files.[13] Some family members have expressed suspicions that Bundy might have been fathered by Louise's own violent, abusive father, Samuel Cowell,[14] but no material evidence has ever been cited to support this.[15]

For the first three years of his life, Bundy lived in the Philadelphia home of his maternal grandparents, Samuel (1898–1983) and Eleanor Cowell (1895–1971), who raised him as their son to avoid the social stigma that accompanied birth outside of wedlock. Family, friends, and even young Ted were told that his grandparents were his parents and that his mother was his older sister. He eventually discovered the truth, although he had varied recollections of the circumstances. He told a girlfriend that a cousin showed him a copy of his birth certificate after calling him a "bastard,"[16] but he told biographers Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth that he found the certificate himself.[11] Biographer and true crime writer Ann Rule, who knew Bundy personally, believed that he did not find out until 1969, when he located his original birth record in Vermont.[17] Bundy expressed a lifelong resentment toward his mother for never talking to him about his real father, and for leaving him to discover his true parentage for himself.[18]

In some interviews, Bundy spoke warmly of his grandparents[19] and told Rule that he "identified with," "respected," and "clung to" his grandfather.[20] In 1987, however, he and other family members told attorneys that Samuel Cowell was a tyrannical bully and a bigot who hated blacks, Italians, Catholics, and Jews, beat his wife and the family dog, and swung neighborhood cats by their tails. He once threw Louise's younger sister Julia down a flight of stairs for oversleeping.[21] He sometimes spoke aloud to unseen presences,[22] and at least once flew into a violent rage when the question of Bundy's paternity was raised.[21]

Bundy described his grandmother as a timid and obedient woman who periodically underwent electroconvulsive therapy for depression[22] and feared to leave their house toward the end of her life.[23] Bundy occasionally exhibited disturbing behavior at an early age. Julia recalled awakening from a nap to find herself surrounded by knives from the kitchen and Bundy standing by the bed smiling.[24]

In 1950, Louise changed her surname from Cowell to Nelson,[10] and at the urging of multiple family members, she left Philadelphia with her son to live with cousins Alan and Jane Scott in Tacoma, Washington.[25] In 1951 Louise met Johnny Culpepper Bundy (1921–2007), a hospital cook, at an adult singles night at Tacoma's First Methodist Church.[26] They married later that year and Johnny Bundy formally adopted Ted.[26] Johnny and Louise conceived four children of their own, and although Johnny tried to include his adoptive son in camping trips and other family activities, Ted remained distant. He later complained to his girlfriend that Johnny wasn't his real father, "wasn't very bright," and "didn't make much money."[27]

Bundy had different recollections of Tacoma when he spoke to his biographers. When he talked to Michaud and Aynesworth, he described how he roamed his neighborhood, picking through trash barrels in search of pictures of naked women.[28] When he spoke to Polly Nelson, he explained how he perused detective magazines, crime novels, and true crime documentaries for stories that involved sexual violence, particularly when the stories were illustrated with pictures of dead or maimed bodies.[29] In a letter to Rule, he asserted that he "never, ever read fact-detective magazines, and shuddered at the thought" that anyone would.[30] In his conversation with Michaud, he described how he would consume large quantities of alcohol and "canvass the community" late at night in search of undraped windows where he could observe women undressing, or "whatever [else] could be seen."[31]

Bundy also varied the accounts of his social life. He told Michaud and Aynesworth that he "chose to be alone" as an adolescent because he was unable to understand interpersonal relationships.[32] He claimed that he had no natural sense of how to develop friendships. "I didn't know what made people want to be friends," he said. "I didn't know what underlay social interactions."[33] Classmates from Woodrow Wilson High School told Rule, however, that Bundy was "well known and well liked" there, "a medium-sized fish in a large pond."[34]

Downhill skiing was Bundy's only significant athletic avocation; he enthusiastically pursued the activity by using stolen equipment and forged lift tickets.[11]

During high school, he was arrested at least twice on suspicion of burglary and auto theft. When he reached age 18, the details of the incidents were expunged from his record, which is customary in Washington.[35]

University years

After graduating from high school in 1965, Bundy attended the University of Puget Sound (UPS) for one year before transferring to the University of Washington (UW) to study Chinese.[36] In 1967, he became romantically involved with a UW classmate who is identified by several pseudonyms in Bundy biographies, most commonly "Stephanie Brooks."[37] In early 1968 he dropped out of college and worked at a series of minimum-wage jobs. He also volunteered at the Seattle office of Nelson Rockefeller's presidential campaign[38] and became Arthur Fletcher's driver and bodyguard during Fletcher's campaign for Lieutenant Governor of Washington State.[39]

In August of that year, Bundy attended the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami as a Rockefeller delegate.[40] Shortly thereafter Brooks ended their relationship and returned to her family home in California, frustrated by what she described as Bundy's immaturity and lack of ambition. Psychiatrist Dorothy Lewis would later pinpoint this crisis as "probably the pivotal time in his development".[41] Devastated by Brooks' rejection, Bundy traveled to Colorado and then farther east, visiting relatives in Arkansas and Philadelphia and enrolling for one semester at Temple University.[42] It was at this time in early 1969, Rule believes, that Bundy visited the office of birth records in Burlington and confirmed his true parentage.[42][43]

Bundy was back in Washington by the fall of 1969 when he met Elizabeth Kloepfer (identified in Bundy literature as Meg Anders, Beth Archer, or Liz Kendall), a divorcée from Ogden, Utah who worked as a secretary at the University of Washington School of Medicine.[44] Their stormy relationship would continue well past his initial incarceration in Utah in 1976.

In mid-1970, Bundy, now focused and goal-oriented, re-enrolled at UW, this time as a psychology major. He became an honor student and was well regarded by his professors.[45] In 1971, he took a job at Seattle's Suicide Hotline Crisis Center, where he met and worked alongside Ann Rule, a former Seattle police officer. An aspiring crime writer, she would later write one of the definitive Bundy biographies, The Stranger Beside Me. Rule saw nothing disturbing in Bundy's personality at the time, and described him as "kind, solicitous, and empathetic".[46]

After graduating from UW in 1972,[47] Bundy joined Governor Daniel J. Evans' re-election campaign.[48] Posing as a college student, he shadowed Evans' opponent, former governor Albert Rosellini, and recorded his stump speeches for analysis by Evans' team.[49][50] Paradoxically, Evans appointed Bundy to the Seattle Crime Prevention Advisory Committee.[51] After Evans was re-elected, Bundy was hired as an assistant to Ross Davis, Chairman of the Washington State Republican Party. Davis thought well of Bundy and described him as "smart, aggressive ... and a believer in the system".[52] In early 1973, despite mediocre LSAT scores, Bundy was accepted into the law schools of UPS and the University of Utah on the strength of letters of recommendation from Evans, Davis, and several UW psychology professors.[53][54]

During a trip to California on Republican Party business in the summer of 1973, Bundy rekindled his relationship with Brooks. She marveled at his transformation into a serious, dedicated professional who was seemingly on the cusp of a legal and political career. He continued to date Kloepfer as well; neither woman was aware of the other's existence. In the fall of 1973, Bundy matriculated at UPS Law School,[55] and continued courting Brooks, who flew to Seattle several times to stay with him. They discussed marriage; at one point he introduced her to Davis as his fiancée.[27]

In January 1974, however, he abruptly broke off all contact. Her phone calls and letters went unreturned. Finally reaching him by phone a month later, Brooks demanded to know why Bundy had unilaterally ended their relationship without explanation. In a flat, calm voice, he replied, "Stephanie, I have no idea what you mean" and hung up. She never heard from him again.[56] He later explained, "I just wanted to prove to myself that I could have married her".[57] Brooks concluded in retrospect that he had deliberately planned the entire courtship and rejection in advance as vengeance for the breakup she initiated in 1968.[56]

By then, Bundy had begun skipping classes at law school. By April, he had stopped attending entirely,[58] as young women began to disappear in the Pacific Northwest.[59]

First two series of murders

Washington, Oregon

There is no consensus on when or where Bundy began killing women. He told different stories to different people and refused to divulge the specifics of his earliest crimes, even as he confessed in graphic detail to dozens of later murders in the days preceding his execution.[60] He told Nelson that he attempted his first kidnapping in 1969 in Ocean City, New Jersey, but did not kill anyone until sometime in 1971 in Seattle.[61] He told psychologist Art Norman that he killed two women in Atlantic City in 1969 while visiting family in Philadelphia.[62][63]

He hinted but refused to elaborate to homicide detective Robert D. Keppel that he committed a murder in Seattle in 1972,[64] and another murder in 1973 that involved a hitchhiker near Tumwater.[65] Rule and Keppel both believed that he might have started killing as a teenager.[66][67] Circumstantial evidence suggested that he may have abducted and killed eight-year-old Ann Marie Burr of Tacoma when he was 14 years old in 1961, an allegation that he repeatedly denied.[64] His earliest documented homicides were committed in 1974 when he was 27 years old. By then, by his own admission, he had mastered the necessary skills—in the era before DNA profiling—to leave minimal incriminating forensic evidence at crime scenes.[68]

Shortly after midnight on January 4, 1974 (around the time that he terminated his relationship with Brooks), Bundy entered the basement apartment of 18-year-old Karen Sparks[69] (identified as Joni Lenz,[70][71] Mary Adams,[72] and Terri Caldwell[73] by various sources), a dancer and student at UW. After bludgeoning the sleeping woman senseless with a metal rod from her bed frame, he sexually assaulted her with either the same rod,[74][57] or a metal speculum,[71] causing extensive internal injuries. She remained unconscious for 10 days,[73] but survived with permanent physical and mental disabilities.[75] In the early morning hours of February 1, Bundy broke into the basement room of Lynda Ann Healy, a UW undergraduate who broadcast morning radio weather reports for skiers. He beat her unconscious, dressed her in blue jeans, a white blouse, and boots, and carried her away.[76]

During the first half of 1974, female college students disappeared at the rate of about one per month. On March 12, Donna Gail Manson, a 19-year-old student at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, 60 miles (95 km) southwest of Seattle, left her dormitory to attend a jazz concert on campus, but never arrived. On April 17, Susan Elaine Rancourt disappeared while on her way to her dorm room after an evening advisors' meeting at Central Washington State College in Ellensburg, 110 miles (175 km) east-southeast of Seattle.[77][78] Two female Central Washington students later came forward to report encounters—one on the night of Rancourt's disappearance, the other three nights earlier—with a man wearing an arm sling, asking for help carrying a load of books to his brown or tan Volkswagen Beetle.[79][80] On May 6, Roberta Kathleen Parks left her dormitory at Oregon State University in Corvallis, 85 miles (135 km) south of Portland, to have coffee with friends at the Memorial Union, but never arrived.[81]

Detectives from the King County and Seattle police departments grew increasingly concerned. There was no significant physical evidence, and the missing women had little in common, apart from being young, attractive, white college students with long hair parted in the middle.[82] On June 1, Brenda Carol Ball, 22, disappeared after leaving the Flame Tavern in Burien, near Seattle–Tacoma International Airport. She was last seen in the parking lot, talking to a brown-haired man with his arm in a sling.[83]

In the early hours of June 11, UW student Georgann Hawkins vanished while walking down a brightly lit alley between her boyfriend's dormitory residence and her sorority house.[84] The next morning, three Seattle homicide detectives and a criminalist combed the entire alleyway on their hands and knees, finding nothing.[85] After Hawkins' disappearance was publicized, witnesses came forward to report seeing a man that night who was in an alley behind a nearby dormitory. He was on crutches with a leg cast and was struggling to carry a briefcase.[86] One woman recalled that the man asked her to help him carry the case to his car, a light brown Volkswagen Beetle.[87]

During this period, Bundy was working in Olympia as the Assistant Director of the Seattle Crime Prevention Advisory Commission (where he wrote a pamphlet for women on rape prevention).[88] Later, he worked at the Department of Emergency Services (DES), a state government agency involved in the search for the missing women. At DES he met and dated Carole Ann Boone, a twice-divorced mother of two who, six years later, would play an important role in the final phase of his life.[89]

Reports of the six missing women and Sparks' brutal beating appeared prominently in newspapers and on television throughout Washington and Oregon.[92] Fear spread among the population; hitchhiking by young women dropped sharply.[93] Pressure mounted on law enforcement agencies,[94] but the paucity of physical evidence severely hampered them. Police could not provide reporters with the little information that was available for fear of compromising the investigation.[95] Further similarities between the victims were noted: The disappearances all took place at night, usually near ongoing construction work, within a week of midterm or final exams; all of the victims were wearing slacks or blue jeans; and at most crime scenes, there were sightings of a man wearing a cast or a sling, and driving a brown or tan Volkswagen Beetle.[96]

The Pacific Northwest murders culminated on July 14, with the broad daylight abductions of two women from a crowded beach at Lake Sammamish State Park in Issaquah, a suburb 20 miles (30 km) east of Seattle.[97] Five female witnesses described an attractive young man wearing a white tennis outfit with his left arm in a sling, speaking with a light accent, perhaps Canadian or British. Introducing himself as "Ted," he asked their help in unloading a sailboat from his tan or bronze-colored Volkswagen Beetle. Four refused; one accompanied him as far as his car, saw that there was no sailboat, and fled. Three additional witnesses saw him approach Janice Anne Ott, 23, a probation case worker at the King County Juvenile Court, with the sailboat story, and watched her leave the beach in his company.[98] About four hours later, Denise Marie Naslund, a 19-year-old woman who was studying to become a computer programmer, left a picnic to go to the restroom and never returned.[99] Bundy told both Stephen Michaud and William Hagmaier that Ott was still alive when he returned with Naslund—and that he forced one to watch as he murdered the other[100][101][102]—but he later denied it in an interview with Lewis on the eve of his execution.[103]

King County police, finally armed with a detailed description of their suspect and his car, posted fliers throughout the Seattle area. A composite sketch was printed in regional newspapers and broadcast on local television stations. Elizabeth Kloepfer, Ann Rule, a DES employee, and a UW psychology professor all recognized the profile, the sketch, and the car, and reported Bundy as a possible suspect;[104] but detectives—who were receiving up to 200 tips per day[105]—thought it unlikely that a clean-cut law student with no adult criminal record could be the perpetrator.[106]

On September 6, two grouse hunters stumbled across the skeletal remains of Ott and Naslund near a service road in Issaquah, 2 miles (3 km) east of Lake Sammamish State Park.[97][107] An extra femur and several vertebrae found at the site were later identified by Bundy as Georgann Hawkins'.[108] Six months later, forestry students from Green River Community College discovered the skulls and mandibles of Healy, Rancourt, Parks, and Ball on Taylor Mountain, where Bundy frequently hiked, just east of Issaquah.[109] Manson's remains were never recovered.

Idaho, Utah, Colorado

In August 1974, Bundy received a second acceptance from the University of Utah Law School and moved to Salt Lake City, leaving Kloepfer in Seattle. While he called Kloepfer often, he dated "at least a dozen" other women.[111] When he studied the first-year law curriculum a second time, "he was devastated to find out that the other students had something, some intellectual capacity, that he did not. He found the classes completely incomprehensible. 'It was a great disappointment to me,' he said."[112]

A new string of homicides began the following month, including two that would remain undiscovered until Bundy confessed to them shortly before his execution. On September 2, he raped and strangled a still-unidentified hitchhiker in Idaho, then either disposed of the remains immediately in a nearby river,[113] or returned the next day to photograph and dismember the corpse.[114][115] On October 2, he seized 16-year-old Nancy Wilcox in Holladay, a suburb of Salt Lake City.[116] [117] Her remains were buried near Capitol Reef National Park, some 200 miles (320 km) south of Holladay, but were never found.[118]

On October 18, Melissa Anne Smith—the 17-year-old daughter of the police chief of Midvale (another Salt Lake City suburb)—disappeared after leaving a pizza parlor. Her nude body was found in a nearby mountainous area nine days later. Postmortem examination indicated that she may have remained alive for up to seven days following her disappearance.[119][120] On October 31, Laura Ann Aime, also 17, disappeared 25 miles (40 km) south in Lehi after leaving a café just after midnight.[121] Her naked body was found by hikers 9 miles (14 km) to the northeast in American Fork Canyon on Thanksgiving Day.[122] Both women had been beaten, raped, sodomized, and strangled with nylon stockings.[123][124] Years later, Bundy described his postmortem rituals with the corpses of Smith and Aime, including hair shampooing and application of makeup.[125][126]

In the late afternoon of November 8, Bundy approached 18-year-old telephone operator Carol DaRonch at Fashion Place Mall in Murray,[127] less than a mile from the Midvale restaurant where Melissa Smith was last seen. He identified himself as "Officer Roseland" of the Murray Police Department and told DaRonch that someone had attempted to break into her car. He asked her to accompany him to the station to file a complaint. When DaRonch pointed out to Bundy that he was driving on a road that did not lead to the police station, he immediately pulled to the shoulder and attempted to handcuff her. During their struggle, he inadvertently fastened both handcuffs to the same wrist, and DaRonch was able to open the car door and escape.[128] Later that evening, Debra Jean Kent, a 17-year-old student at Viewmont High School in Bountiful, 20 miles (30 km) north of Murray, disappeared after leaving a theater production at the school to pick up her brother.[129] The school's drama teacher and a student told police that "a stranger" had asked each of them to come out to the parking lot to identify a car. Another student later saw the same man pacing in the rear of the auditorium, and the drama teacher spotted him again shortly before the end of the play.[130] Outside the auditorium, investigators found a key that unlocked the handcuffs removed from Carol DaRonch's wrist.[131]

In November, Elizabeth Kloepfer called King County police a second time after reading that young women were disappearing in towns surrounding Salt Lake City. Detective Randy Hergesheimer of the Major Crimes division interviewed her in detail. By then, Bundy had risen considerably on the King County hierarchy of suspicion, but the Lake Sammamish witness considered most reliable by detectives failed to identify him from a photo lineup.[132] In December, Kloepfer called the Salt Lake County Sheriff's Office and repeated her suspicions. Bundy's name was added to their list of suspects, but at that time no credible forensic evidence linked him to the Utah crimes.[133] In January 1975, Bundy returned to Seattle after his final exams and spent a week with Kloepfer, who did not tell him that she had reported him to police on three separate occasions. She made plans to visit him in Salt Lake City in August.[134]

In 1975, Bundy shifted much of his criminal activity eastward, from his base in Utah to Colorado. On January 12, a 23-year-old registered nurse named Caryn Eileen Campbell disappeared while walking down a well-lit hallway between the elevator and her room at the Wildwood Inn (now the Wildwood Lodge) in Snowmass Village, 400 miles (640 km) southeast of Salt Lake City.[135] Her nude body was found a month later next to a dirt road just outside the resort. She had been killed by blows to her head from a blunt instrument that left distinctive linear grooved depressions on her skull; her body also bore deep cuts from a sharp weapon.[136] On March 15, 100 miles (160 km) northeast of Snowmass, Vail ski instructor Julie Cunningham, 26, disappeared while walking from her apartment to a dinner date with a friend. Bundy later told Colorado investigators that he approached Cunningham on crutches and asked her to help carry his ski boots to his car, where he clubbed and handcuffed her, then assaulted and strangled her at a secondary site near Rifle, 90 miles (140 km) west of Vail.[137][138] Weeks later, he made the six-hour drive from Salt Lake City to revisit her remains.[139][138]

Denise Lynn Oliverson, 25, disappeared near the Utah–Colorado border in Grand Junction on April 6 while riding her bicycle to her parents' house; her bike and sandals were found under a viaduct near a railroad bridge.[140] On May 6, Bundy lured 12-year-old Lynette Dawn Culver from Alameda Junior High School in Pocatello, Idaho, 160 miles (255 km) north of Salt Lake City. He drowned and then sexually assaulted her in his hotel room,[141] before disposing of her body in a river north of Pocatello (possibly the Snake).[142][143]

In mid-May, three of Bundy's Washington State DES coworkers, including Carole Ann Boone, visited him in Salt Lake City and stayed for a week in his apartment. Bundy subsequently spent a week in Seattle with Kloepfer in early June and they discussed getting married the following Christmas. Again, Kloepfer made no mention of her multiple discussions with the King County Police and Salt Lake County Sheriff's Office. Bundy disclosed neither his ongoing relationship with Boone nor a concurrent romance with a Utah law student known in various accounts as Kim Andrews[144] or Sharon Auer.[145]

On June 28, Susan Curtis vanished from the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo, 45 miles (70 km) south of Salt Lake City. Curtis' murder became Bundy's last confession, tape-recorded moments before he entered the execution chamber.[146] The bodies of Wilcox, Kent, Cunningham, Oliverson, Culver, and Curtis were never recovered.

In August or September 1975, Bundy was baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, although he was not an active participant in services and ignored most church restrictions.[147][148][149] He would later be excommunicated by the LDS Church following his 1976 kidnapping conviction.[147] When asked his religious preference after his arrest, Bundy answered "Methodist", the religion of his childhood.[150]

In Washington state, investigators were still struggling to analyze the Pacific Northwest murder spree that had ended as abruptly as it had begun. In an effort to make sense of an overwhelming mass of data, they resorted to the then-innovative strategy of compiling a database. They used the King County payroll computer, a "huge, primitive machine" by contemporary standards, but the only one available for their use. After inputting the many lists they had compiled—classmates and acquaintances of each victim, Volkswagen owners named "Ted", known sex offenders, and so on—they queried the computer for coincidences. Out of thousands of names, 26 turned up on four separate lists; one was Ted Bundy. Detectives also manually compiled a list of their 100 "best" suspects, and Bundy was on that list as well. He was "literally at the top of the pile" of suspects when word came from Utah of his arrest.[151]

Arrest and first trial

On August 16, 1975, Bundy was arrested by Utah Highway Patrol officer Bob Hayward in Granger (another Salt Lake City suburb).[152] Hayward had observed Bundy cruising a residential area in the pre-dawn hours; Bundy fled the area at high speed after seeing the patrol car.[153] The officer searched the car after he noticed that the Volkswagen's front passenger seat had been removed and placed on the rear seats. He found a ski mask, a second mask fashioned from pantyhose, a crowbar, handcuffs, trash bags, a coil of rope, an ice pick, and other items initially assumed to be burglary tools. Bundy explained that the ski mask was for skiing, he had found the handcuffs in a dumpster, and the rest were common household items.[154] However, Detective Jerry Thompson remembered a similar suspect and car description from the November 1974 DaRonch kidnapping, which matched Bundy's name from Kloepfer's December 1974 phone call. In a search of Bundy's apartment, police found a guide to Colorado ski resorts with a checkmark by the Wildwood Inn[155] and a brochure that advertised the Viewmont High School play in Bountiful, where Debra Kent had disappeared.[156] The police did not have sufficient evidence to detain Bundy, and he was released on his own recognizance. Bundy later said that searchers missed a hidden collection of Polaroid photographs of his victims, which he destroyed after he was released.[157]

Salt Lake City police placed Bundy on 24-hour surveillance, and Thompson flew to Seattle with two other detectives to interview Kloepfer. She told them that in the year prior to Bundy's move to Utah, she had discovered objects that she "couldn't understand" in her house and in Bundy's apartment. These items included crutches, a bag of plaster of Paris that he admitted stealing from a medical supply house, and a meat cleaver that was never used for cooking. Additional objects included surgical gloves, an Oriental knife in a wooden case that he kept in his glove compartment, and a sack full of women's clothing.[158] Bundy was perpetually in debt, and Kloepfer suspected that he had stolen almost everything of significant value that he possessed. When she confronted him over a new TV and stereo, he warned her, "If you tell anyone, I'll break your fucking neck."[159] She said Bundy became "very upset" whenever she considered cutting her hair, which was long and parted in the middle. She would sometimes awaken in the middle of the night to find him under the bed covers with a flashlight, examining her body. He kept a lug wrench, taped halfway up the handle, in the trunk of her car—another Volkswagen Beetle, which he often borrowed—"for protection". The detectives confirmed that Bundy had not been with Kloepfer on any of the nights during which the Pacific Northwest victims had vanished, nor on the day Ott and Naslund were abducted.[160] Shortly thereafter, Kloepfer was interviewed by Seattle homicide detective Kathy McChesney, and learned of the existence of Stephanie Brooks and her brief engagement to Bundy around Christmas 1973.[161]

In September, Bundy sold his Volkswagen Beetle to a Midvale teenager.[162] Utah police impounded it, and FBI technicians dismantled and searched it. They found hairs matching samples obtained from Caryn Campbell's body.[163] Later, they also identified hair strands "microscopically indistinguishable" from those of Melissa Smith and Carol DaRonch.[164] FBI lab specialist Robert Neill concluded that the presence of hair strands in one car matching three different victims who had never met one another would be "a coincidence of mind-boggling rarity".[165]

On October 2, detectives put Bundy into a lineup. DaRonch immediately identified him as "Officer Roseland", and witnesses from Bountiful recognized him as the stranger at the high school auditorium.[166] There was insufficient evidence to link him to Debra Kent (whose body was never found, though a skeletal fragment found near the school was later identified as Kent's by DNA analysis[167]). There was more than enough evidence to charge him with aggravated kidnapping and attempted criminal assault in the DaRonch case. He was freed on $15,000 bail, paid by his parents,[168] and spent most of the time between indictment and trial in Seattle, living in Kloepfer's house. Seattle police had insufficient evidence to charge him in the Pacific Northwest murders, but kept him under close surveillance. "When Ted and I stepped out on the porch to go somewhere," Kloepfer wrote, "so many unmarked police cars started up that it sounded like the beginning of the Indy 500."[169]

In November, the three principal Bundy investigators—Jerry Thompson from Utah, Robert Keppel from Washington, and Michael Fisher from Colorado—met in Aspen, Colorado and exchanged information with 30 detectives and prosecutors from five states.[170] While officials left the meeting (later known as the Aspen Summit) convinced that Bundy was the murderer they sought, they agreed that more hard evidence would be needed before he could be charged with any of the murders.[171]

In February 1976, Bundy stood trial for the DaRonch kidnapping. On the advice of his attorney, John O'Connell, Bundy waived his right to a jury due to the negative publicity surrounding the case. After a four-day bench trial and a weekend of deliberation, Judge Stewart Hanson Jr. found him guilty of kidnapping and assault.[172][173][174] In June he was sentenced to one-to-15 years in the Utah State Prison.[168] In October, he was found hiding in bushes in the prison yard carrying an "escape kit"—road maps, airline schedules, and a social security card—and spent several weeks in solitary confinement.[175] Later that month, Colorado authorities charged him with Caryn Campbell's murder. After a period of resistance, he waived extradition proceedings and was transferred to Aspen in January 1977.[176][177]

Escapes

On June 7, 1977, Bundy was transported 40 miles (64 km) from the Garfield County jail in Glenwood Springs to Pitkin County Courthouse in Aspen for a preliminary hearing. He had elected to serve as his own attorney, and as such, was excused by the judge from wearing handcuffs or leg shackles.[179] During a recess, he asked to visit the courthouse's law library to research his case. While shielded from his guards' view behind a bookcase, he opened a window and jumped to the ground from the second story, injuring his right ankle as he landed. After shedding an outer layer of clothing, he walked through Aspen as roadblocks were being set up on its outskirts, then hiked southward onto Aspen Mountain. Near its summit he broke into a hunting cabin and stole food, clothing, and a rifle.[180] The following day he left the cabin and continued south toward the town of Crested Butte, but became lost in the forest. For two days he wandered aimlessly on the mountain, missing two trails that led downward to his intended destination. On June 10, he broke into a camping trailer on Maroon Lake, 10 miles (16 km) south of Aspen, taking food and a ski parka; but instead of continuing southward, he walked back north toward Aspen, eluding roadblocks and search parties along the way.[181] Three days later, he stole a car at the edge of Aspen Golf Course. Cold, sleep-deprived, and in constant pain from his sprained ankle, he drove back into Aspen, where two police officers noticed his car weaving in and out of its lane and pulled him over. He had been a fugitive for six days.[182] In the car were maps of the mountain area around Aspen that prosecutors were using to demonstrate the location of Caryn Campbell's body (as his own attorney, Bundy had rights of discovery), indicating that his escape was not a spontaneous act, but had been planned.[183]

Back in jail in Glenwood Springs, Bundy ignored the advice of friends and legal advisors to stay put. The case against him, already weak at best, was deteriorating steadily as pretrial motions consistently resolved in his favor and significant bits of evidence were ruled inadmissible.[185] "A more rational defendant might have realized that he stood a good chance of acquittal, and that beating the murder charge in Colorado would probably have dissuaded other prosecutors... with as little as a year and a half to serve on the DaRonch conviction, had Ted persevered, he could have been a free man."[186] Instead, Bundy assembled a new escape plan. He acquired a detailed floor plan of the jail and a hacksaw blade from other inmates, and accumulated $500 in cash, smuggled in over a six-month period, he later said, by visitors—Carole Ann Boone in particular.[187] During the evenings, while other prisoners were showering, he sawed a hole about one square foot (0.093 m²) between the steel reinforcing bars in his cell's ceiling and, having lost 35 pounds (16 kg), was able to wriggle through it into the crawl space above.[188] In the weeks that followed, he made a series of practice runs, exploring the space. Multiple reports from an informant of movement within the ceiling during the night were not investigated.[189]

By late 1977, Bundy's impending trial had become a cause célèbre in the small town of Aspen, and Bundy filed a motion for a change of venue to Denver.[190] On December 23, the Aspen trial judge granted the request—but to Colorado Springs, where juries had historically been hostile to murder suspects.[191] On the night of December 30, with most of the jail staff on Christmas break and nonviolent prisoners on furlough with their families,[192] Bundy piled books and files in his bed, covered them with a blanket to simulate his sleeping body, and climbed into the crawl space. He broke through the ceiling into the apartment of the chief jailer—who was out for the evening with his wife[193]—changed into street clothes from the jailer's closet, and walked out the front door to freedom.[194]

After stealing a car, Bundy drove eastward out of Glenwood Springs, but the car soon broke down in the mountains on Interstate 70. A passing motorist gave him a ride into Vail, 60 miles (97 km) to the east. From there he caught a bus to Denver, where he boarded a morning flight to Chicago. In Glenwood Springs, the jail's skeleton crew did not discover the escape until noon on December 31, more than 17 hours later. By then, Bundy was already in Chicago.[195]

Florida

From Chicago, Bundy traveled by train to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he was present in a local tavern on January 2.[196] Five days later, he stole a car and drove to Atlanta, where he boarded a bus and arrived in Tallahassee, Florida, on the morning of January 8. He rented a room under the alias Chris Hagen at the Holiday Inn near the Florida State University (FSU) campus.[197] Bundy later said that he initially resolved to find legitimate employment and refrain from further criminal activity, knowing he could probably remain free and undetected in Florida indefinitely as long as he did not attract the attention of police;[198] but his lone job application, at a construction site, had to be abandoned when he was asked to produce identification.[199] He reverted to his old habits of shoplifting and stealing credit cards from women's wallets left in shopping carts.[200]

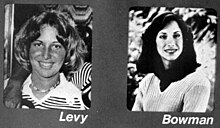

In the early hours of January 15, 1978—one week after his arrival in Tallahassee—Bundy entered FSU's Chi Omega sorority house through a rear door with a faulty locking mechanism.[201] Beginning at about 2:45 a.m. he bludgeoned Margaret Bowman, 21, with a piece of oak firewood as she slept, then garroted her with a nylon stocking.[202] He then entered the bedroom of 20-year-old Lisa Levy and beat her unconscious, strangled her, tore one of her nipples, bit deeply into her left buttock, and sexually assaulted her with a hair mist bottle.[203] In an adjoining bedroom he attacked Kathy Kleiner, breaking her jaw and deeply lacerating her shoulder; and Karen Chandler, who suffered a concussion, broken jaw, loss of teeth, and a crushed finger.[204] Chandler and Kleiner survived the attack; Kleiner later attributed their survival to automobile headlights illuminating the interior of their room and frightening away the attacker.[205] Tallahassee detectives later determined that the four attacks took place in a total of less than 15 minutes, within earshot of more than 30 witnesses who heard nothing.[201] After leaving the sorority house, Bundy broke into a basement apartment eight blocks away and attacked FSU student Cheryl Thomas, dislocating her shoulder and fracturing her jaw and skull in five places. She was left with permanent deafness, and equilibrium damage that ended her dance career.[206] On Thomas' bed, police found a semen stain and a pantyhose "mask" containing two hairs "similar to Bundy's in class and characteristic".[207][208]

On February 8, Bundy drove 150 miles (240 km) east to Jacksonville, in a stolen FSU van. In a parking lot he approached 14-year-old Leslie Parmenter, the daughter of Jacksonville Police Department's Chief of Detectives, identifying himself as "Richard Burton, Fire Department", but retreated when Parmenter's older brother arrived and challenged him.[209] That afternoon, he backtracked 60 miles (97 km) westward to Lake City. At Lake City Junior High School the following morning, 12-year-old Kimberly Dianne Leach was summoned to her homeroom by a teacher to retrieve a forgotten purse; she never returned to class. Seven weeks later, after an intensive search, her partially mummified remains were found in a pig farrowing shed near Suwannee River State Park, 35 miles (56 km) northwest of Lake City.[210][211] She appeared to have been raped, with her underwear found near the body containing semen, and killed by violence to the neck with a knife.[212][213]

On February 12, with insufficient cash to pay his overdue rent and a growing suspicion that police were closing in on him,[214] Bundy stole a car and fled Tallahassee, driving westward across the Florida Panhandle. Three days later, at around 1:00 am, he was stopped by Pensacola police officer David Lee near the Alabama state line after a "wants and warrants" check showed his Volkswagen Beetle was stolen.[215] When told he was under arrest, Bundy kicked Lee's legs out from under him and took off running. Lee fired a warning shot followed by a second round, gave chase and tackled him. The two struggled over Lee's gun before the officer finally subdued and arrested Bundy.[216] In the stolen vehicle were three sets of IDs belonging to female FSU students, 21 stolen credit cards and a stolen television set.[217] Also found were a pair of dark-rimmed non-prescription glasses and a pair of plaid slacks, later identified as the disguise worn by "Richard Burton, Fire Department" in Jacksonville.[218] As Lee transported his suspect to jail, unaware that he had just arrested one of the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives, he heard Bundy say, "I wish you had killed me."[219]

Florida trials, marriage

Following a change of venue to Miami, Bundy stood trial for the Chi Omega homicides and assaults in June 1979.[220] The trial was covered by 250 reporters from five continents and was the first to be televised nationally in the United States.[221] Despite the presence of five court-appointed attorneys, Bundy again handled much of his own defense. From the beginning, he "sabotaged the entire defense effort out of spite, distrust, and grandiose delusion", Nelson later wrote. "Ted [was] facing murder charges, with a possible death sentence, and all that mattered to him apparently was that he be in charge."[222]

According to Mike Minerva, a Tallahassee public defender and member of the defense team, a pre-trial plea bargain was negotiated in which Bundy would plead guilty to killing Levy, Bowman and Leach in exchange for a firm 75-year prison sentence. Prosecutors were amenable to a deal, by one account, because "prospects of losing at trial were very good."[223] Bundy, on the other hand, saw the plea deal not only as a means of avoiding the death penalty, but also as a "tactical move": he could enter his plea, then wait a few years for evidence to disintegrate or become lost and for witnesses to die, move on, or retract their testimony. Once the case against him had deteriorated beyond repair, he could file a post-conviction motion to set aside the plea and secure an acquittal.[224][225] At the last minute, however, Bundy refused the deal. "It made him realize he was going to have to stand up in front of the whole world and say he was guilty", Minerva said. "He just couldn't do it."[226]

At trial, crucial testimony came from Chi Omega sorority members Connie Hastings, who placed Bundy in the vicinity of the Chi Omega House that evening,[227] and Nita Neary, who saw him leaving the sorority house clutching the oak murder weapon.[228][229] Incriminating physical evidence included impressions of the bite wounds Bundy had inflicted on Lisa Levy's left buttock, which forensic odontologists Richard Souviron and Lowell Levine matched to castings of Bundy's teeth.[230][231] The jury deliberated for less than seven hours before convicting him on July 24, 1979, of the Bowman and Levy murders, three counts of attempted first degree murder (for the assaults on Kleiner, Chandler and Thomas) and two counts of burglary. Trial judge Edward Cowart imposed death sentences for the murder convictions.[232][233]

Six months later, a second trial took place in Orlando, for the abduction and murder of Kimberly Leach.[234] Bundy was found guilty once again, after less than eight hours' deliberation, due principally to the testimony of an eyewitness who saw him leading Leach from the schoolyard to his stolen van.[235] Important material evidence included clothing fibers with an unusual manufacturing error, found in the van and on Leach's body, which matched fibers from the jacket Bundy was wearing when he was arrested.[236]

During the penalty phase of the trial, Bundy took advantage of an obscure Florida law providing that a marriage declaration in court, in the presence of a judge, constituted a legal marriage. As he was questioning former Washington State DES coworker Carole Ann Boone—who had moved to Florida to be near Bundy, had testified on his behalf during both trials, and was again testifying on his behalf as a character witness—he asked her to marry him. She accepted, and Bundy declared to the court that they were legally married.[237][238]

On February 10, 1980, Bundy was sentenced for a third time to death by electrocution.[239] As the sentence was announced, he reportedly stood and shouted, "Tell the jury they were wrong!"[240] This third death sentence would be the one ultimately carried out nearly nine years later.[241]

In October 1981, Boone gave birth to a daughter and named Bundy as the father.[242][15][243] While conjugal visits were not allowed at Raiford Prison, inmates were known to pool their money in order to bribe guards to allow them intimate time alone with their female visitors.[15][244]

Death row, confessions and death

Shortly after the conclusion of the Leach trial and the beginning of the long appeals process that followed, Bundy initiated a series of interviews with Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth. Speaking mostly in third person to avoid "the stigma of confession", he began for the first time to divulge details of his crimes and thought processes.[245]

He recounted his career as a thief, confirming Kloepfer's long-time suspicion that he had shoplifted virtually everything of substance that he owned.[246] "The big payoff for me," he said, "was actually possessing whatever it was I had stolen. I really enjoyed having something ... that I had wanted and gone out and taken." Possession proved to be an important motive for rape and murder as well.[247] Sexual assault, he said, fulfilled his need to "totally possess" his victims.[248] At first, he killed his victims "as a matter of expediency ... to eliminate the possibility of [being] caught"; but later, murder became part of the "adventure". "The ultimate possession was, in fact, the taking of the life", he said. "And then ... the physical possession of the remains."[249]

Bundy also confided in Special Agent William Hagmaier of the FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit. Hagmaier was struck by the "deep, almost mystical satisfaction" that Bundy took in murder. "He said that after a while, murder is not just a crime of lust or violence", Hagmaier related. "It becomes possession. They are part of you ... [the victim] becomes a part of you, and you [two] are forever one ... and the grounds where you kill them or leave them become sacred to you, and you will always be drawn back to them." Bundy told Hagmaier that he considered himself to be an "amateur", an "impulsive" killer in his early years, before moving into what he termed his "prime" or "predator" phase at about the time of Lynda Healy's murder in 1974. This implied that he began killing well before 1974—although he never explicitly admitted to having done so.[250]

In July 1984, Raiford guards found two hacksaw blades that Bundy had hidden in his cell. A steel bar in one of the cell's windows had been sawed completely through at the top and bottom and glued back into place with a homemade soap-based adhesive.[251][252] Several months later, guards found an unauthorized mirror hidden in the cell, and Bundy was again moved to a different cell.[253]

Shortly thereafter, he was charged with a disciplinary infraction for unauthorized correspondence with another high-profile criminal, John Hinckley Jr.[254] In October 1984, Bundy contacted Robert Keppel and offered to share his self-proclaimed expertise in serial killer psychology[253] in the ongoing hunt in Washington for the "Green River Killer", later identified as Gary Ridgway.[255] Keppel and Green River Task Force detective Dave Reichert interviewed Bundy, but Ridgway remained at large for a further 17 years.[256] Keppel published a detailed documentation of the Green River interviews,[257] and later collaborated with Michaud on another examination of the interview material.[258] Bundy coined the nickname "The Riverman" for Gary Ridgway, which was later used for the title of Keppel's book, The Riverman: Ted Bundy and I Hunt for the Green River Killer.[259]

In early 1986, an execution date (March 4) was set on the Chi Omega convictions; the Supreme Court issued a brief stay, but the execution was quickly rescheduled.[260] In April, shortly after the new date (July 2) was announced, Bundy finally confessed to Hagmaier and Nelson what they believed was the full range of his depredations, including details of what he did to some of his victims after their deaths. He told them that he revisited Taylor Mountain, Issaquah, and other secondary crime scenes, often several times, to lie with his victims and perform sexual acts with their decomposing bodies until putrefaction forced him to stop. In some cases, he drove for several hours each way and remained the entire night.[139] In Utah, he applied makeup to Melissa Smith's lifeless face, and he repeatedly washed Laura Aime's hair. "If you've got time," he told Hagmaier, "they can be anything you want them to be."[126] He decapitated approximately 12 of his victims with a hacksaw,[38][261] and kept at least one group of severed heads—probably the four later found on Taylor Mountain (Rancourt, Parks, Ball and Healy)—in his apartment for a period of time before disposing of them.[3]

Less than 15 hours before the scheduled July 2 execution, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals stayed it indefinitely and remanded the Chi Omega case for review on multiple technicalities—including Bundy's mental competency to stand trial, and an erroneous instruction by the trial judge during the penalty phase requiring the jury to break a 6–6 tie between life imprisonment and the death penalty[262]—which, ultimately, were never resolved.[263] A new date (November 18, 1986) was then set to carry out the Leach sentence; the Eleventh Circuit Court issued a stay on November 17.[263] In mid-1988, the Eleventh Circuit ruled against Bundy, and in December the Supreme Court denied a motion to review the ruling. Within hours of that final denial, a firm execution date of January 24, 1989, was announced.[264] Bundy's journey through the appeals courts had been unusually rapid for a capital murder case: "Contrary to popular belief, the courts moved Bundy as fast as they could ... Even the prosecutors acknowledged that Bundy's lawyers never employed delaying tactics. Though people everywhere seethed at the apparent delay in executing the archdemon, Ted Bundy was actually on the fast track."[265]

With all appeal avenues exhausted and no further motivation to deny his crimes, Bundy agreed to speak frankly with investigators. He confessed to Keppel that he had committed all eight of the Washington and Oregon homicides for which he was the prime suspect. He described three additional previously unknown victims in Washington and two in Oregon whom he declined to identify (if indeed he ever knew their identities).[266] He said he left a fifth corpse—Donna Manson's—on Taylor Mountain,[267] but incinerated her head in Kloepfer's fireplace. ("Of all the things I did to [Kloepfer]," he told Keppel, "this is probably the one she is least likely to forgive me for. Poor Liz.")[268]

He described in graphic detail his abduction of Georgann Hawkins from the brightly lit UW alley; how he had lured her to his car before rendering her unconscious with a crowbar he had earlier placed beside the vehicle. He then handcuffed her and drove her to Issaquah, where he had strangled her,[269] before spending the entire night with her body. He later revisited her corpse on three different occasions.[270] He also admitted, for the first time, that he returned to the UW alley the morning after Hawkins' abduction and murder. There, in the very midst of a major crime scene investigation, he located and gathered Hawkins' earrings and one of her shoes, where he had left them in the adjoining parking lot, and departed, unobserved. "It was a feat so brazen," wrote Keppel, "that it astonishes police even today."[271]

"He described the Issaquah crime scene [where the bones of Ott, Naslund, and Hawkins were found], and it was almost like he was just there", Keppel said. "Like he was seeing everything. He was infatuated with the idea because he spent so much time there. He is just totally consumed with murder all the time."[272] Nelson's impressions were similar: "It was the absolute misogyny of his crimes that stunned me," she wrote, "his manifest rage against women. He had no compassion at all ... he was totally engrossed in the details. His murders were his life's accomplishments."[157]

Bundy confessed to detectives from Idaho, Utah, and Colorado that he had committed numerous additional homicides, including several that were unknown to the police. He explained that when he was in Utah he could bring his victims back to his apartment, "where he could reenact scenarios depicted on the covers of detective magazines."[38] A new ulterior strategy quickly became apparent: he withheld many details, hoping to parlay the incomplete information into yet another stay of execution. "There are other buried remains in Colorado", he admitted, but refused to elaborate.[273] The new strategy—immediately dubbed "Ted's bones-for-time scheme"—served only to deepen the resolve of authorities to see Bundy executed on schedule, and yielded little new detailed information.[274] In cases where he did give details, nothing was found.[275] Colorado detective Matt Lindvall interpreted this as a conflict between his desire to postpone his execution by divulging information and his need to remain in "total possession—the only person who knew his victims' true resting places."[276]

When it became clear that no further stays would be forthcoming from the courts, Bundy supporters began lobbying for the only remaining option, executive clemency. Diana Weiner, a young Florida attorney and Bundy's last purported love interest,[277] asked the families of several Colorado and Utah victims to petition Florida Governor Bob Martinez for a postponement to give Bundy time to reveal more information.[278] All refused.[279] "The families already believed that the victims were dead and that Ted had killed them", wrote Nelson. "They didn't need his confession."[280] Martinez made it clear that he would not agree to further delays in any case. "We are not going to have the system manipulated", he told reporters. "For him to be negotiating for his life over the bodies of victims is despicable."[281]

Boone had championed Bundy's innocence throughout all of his trials and felt "deeply betrayed" by his admission that he was, in fact, guilty. She moved back to Washington with her daughter and refused to accept his phone call on the morning of his execution. "She was hurt by his relationship with Diana [Weiner]," Nelson wrote, "and devastated by his sudden wholesale confessions in his last days."[282]

Hagmaier was present during Bundy's final interviews with investigators. On the eve of his execution, he talked of suicide. "He did not want to give the state the satisfaction of watching him die", Hagmaier said.[226]

Bundy died in the Raiford electric chair at 7:16 a.m. EST on January 24, 1989; he was 42 years old. Hundreds of revelers—including 20 off-duty police officers, by one account[283]—sang, danced and set off fireworks in a pasture across the street from the prison as the execution was carried out,[284][285] then cheered loudly as the white hearse containing his corpse departed the prison.[286] His body was cremated in Gainesville,[287] and his ashes scattered at an undisclosed location in the Cascade Range of Washington State, in accordance with his will.[283][288]

Modus operandi and victim profiles

Bundy was an unusually organized and calculating criminal who used his extensive knowledge of law enforcement methodologies to elude identification and capture for years.[289] His crime scenes were distributed over large geographic areas; his victim count had risen to at least 20 before it became clear that numerous investigators in widely disparate jurisdictions were hunting the same man.[290] His assault methods of choice were blunt trauma and strangulation, two relatively silent techniques that could be accomplished with common household items.[291] He deliberately avoided firearms due to the noise they made and the ballistic evidence they left behind.[292] He was a "meticulous researcher" who explored his surroundings in minute detail, looking for safe sites to seize and dispose of victims.[293] He was unusually skilled at minimizing physical evidence.[68] His fingerprints were never found at a crime scene, nor any other incontrovertible evidence of his guilt, a fact he repeated often during the years in which he attempted to maintain his innocence.[294]

Other significant obstacles for law enforcement were Bundy's generic, essentially anonymous physical features,[295] and a curious chameleon-like ability to change his appearance almost at will.[296] Early on, police complained of the futility of showing his photograph to witnesses; he looked different in virtually every photo ever taken of him.[297] In person, "his expression would so change his whole appearance that there were moments that you weren't even sure you were looking at the same person", said Stewart Hanson, Jr., the judge in the DaRonch trial. "He [was] really a changeling."[298] Bundy was well aware of this unusual quality and he exploited it, using subtle modifications of facial hair or hairstyle to significantly alter his appearance as necessary.[299] He concealed his one distinctive identifying mark, a dark mole on his neck, with turtleneck shirts and sweaters.[300] Even his Volkswagen Beetle proved difficult to pin down; its color was variously described by witnesses as metallic or non-metallic, tan or bronze, light brown or dark brown.[301]

Bundy's modus operandi evolved in organization and sophistication over time, as is typical of serial killers, according to FBI experts.[38] Early on, it consisted of forcible late-night entry followed by a violent attack with a blunt weapon on a sleeping victim. He left Sparks for dead while Healy was kidnapped.[302] As his methodology evolved Bundy became progressively more organized in his choice of victims and crime scenes. He would employ various ruses designed to lure his victim to the vicinity of his vehicle where he had pre-positioned a weapon, usually a crowbar. In many cases he wore a plaster cast on one leg or a sling on one arm, and sometimes hobbled on crutches, then requested assistance in carrying something to his vehicle. Bundy was regarded as handsome and charismatic, traits he exploited to win the confidence of his victims and the people around him in his daily life.[98][303][304] "Ted lured females", Michaud wrote, "the way a lifeless silk flower can dupe a honey bee."[305] Once he had them near or inside his vehicle, he would overpower and bludgeon them, and then restrain them with handcuffs. He would then transport them to a pre-selected secondary site, often a considerable distance away, and strangle them by ligature during the act of rape. In situations where his looks and charm were not useful, he invoked authority by identifying himself as a police officer or firefighter. Toward the end of his spree, in Florida, perhaps under the stress of being a fugitive, he regressed to indiscriminate attacks on sleeping victims.[306][38]

At secondary sites he would remove and later burn the victim's clothing,[307] or in at least one case (Cunningham's) deposit them in a Goodwill Industries collection bin.[308] Bundy explained that the clothing removal was ritualistic, but also a practical matter, as it minimized the chance of leaving trace evidence at the crime scene that could implicate him.[307] (A manufacturing error in fibers from his own clothing, ironically, provided a crucial incriminating link to Kimberly Leach.)[309] He often revisited his secondary crime scenes to engage in acts of necrophilia,[310] and to groom or dress up the cadavers.[311] Some victims were found wearing articles of clothing they had never worn, or nail polish that family members had never seen.[312] He took Polaroid photos of many of his victims. "When you work hard to do something right," he told Hagmaier, "you don't want to forget it."[126] Consumption of large quantities of alcohol was an "essential component", he told both Keppel and Michaud; he needed to be "extremely drunk" while on the prowl[313][314] in order to "significantly diminish" his inhibitions and to "sedate" the "dominant personality" that he feared might prevent his inner "entity" from acting on his impulses.[315]

All of Bundy's known victims were white females, most of middle-class backgrounds. Almost all were between the ages of 15 and 25 and most were college students. He apparently never approached anyone he might have met before.[289] (In their last conversation before his execution, Bundy told Kloepfer he had purposely stayed away from her "when he felt the power of his sickness building in him.")[316] Rule noted that most of the identified victims had long straight hair, parted in the middle—like Stephanie Brooks, the woman who rejected him, and to whom he later became engaged and then rejected in return. Rule speculated that Bundy's animosity toward his first girlfriend triggered his protracted rampage and caused him to target victims who resembled her.[317] Bundy dismissed this hypothesis: "[T]hey ... just fit the general criteria of being young and attractive", he told Hugh Aynesworth. "Too many people have bought this crap that all the girls were similar ... [but] almost everything was dissimilar ... physically, they were almost all different."[318] He did concede that youth and beauty were "absolutely indispensable criteria" in his choice of victims.[319]

After Bundy's execution, Ann Rule was surprised and troubled to hear from numerous "sensitive, intelligent, kind young women", who wrote or called to say they were deeply depressed because Bundy was dead. Many had corresponded with him, "each believing that she was his only one". Several said they suffered nervous breakdowns when he died. "Even in death, Ted damaged women," Rule wrote. "To get well, they must realize that they were conned by the master conman. They are grieving for a shadow man that never existed."[320]

Pathology

Bundy underwent multiple psychiatric examinations; the experts' conclusions varied. Dorothy Otnow Lewis, Professor of Psychiatry at the New York University School of Medicine and an authority on violent behavior, initially made a diagnosis of bipolar disorder,[321] but later changed her impression more than once.[5][322] She also suggested the possibility of a multiple personality disorder, based on behaviors described in interviews and court testimony: a great-aunt witnessed an episode during which Bundy "seemed to turn into another, unrecognizable person ... [she] suddenly, inexplicably found herself afraid of her favorite nephew as they waited together at a dusk-darkened train station. He had turned into a stranger."[22] Lewis recounted a prison official in Tallahassee describing a similar transformation: "He said, 'He became weird on me.' He did a metamorphosis, a body and facial change, and he felt there was almost an odor emitting from him. He said, 'Almost a complete change of personality ... that was the day I was afraid of him.'"[323]

While experts found Bundy's precise diagnosis elusive, the majority of evidence pointed away from bipolar disorder or other psychoses,[324] and toward antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).[325] Bundy displayed many personality traits typically found in ASPD patients (who are often identified as "sociopaths" or "psychopaths"[326]), such as outward charm and charisma with little true personality or genuine insight beneath the facade;[327] the ability to distinguish right from wrong, but with minimal effect on behavior;[328][329] and an absence of guilt or remorse.[327] "Guilt doesn't solve anything, really", Bundy said, in 1981. "It hurts you ... I guess I am in the enviable position of not having to deal with guilt."[330] There was also evidence of narcissism, poor judgment, and manipulative behavior. "Sociopaths", prosecutor George Dekle wrote, "are egotistical manipulators who think they can con anybody."[331] "Sometimes he manipulates even me", admitted one psychiatrist.[332] In the end, Lewis agreed with the majority: "I always tell my graduate students that if they can find me a real, true psychopath, I'll buy them dinner", she told Nelson. "I never thought they existed ... but I think Ted may have been one, a true psychopath, without any remorse or empathy at all."[333] Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) has been proposed as an alternative diagnosis in at least one subsequent retrospective analysis.[334]

On the afternoon before he was executed, Bundy granted an interview to James Dobson, a psychologist and founder of the Christian evangelical organization Focus on the Family.[335] He used the opportunity to make new claims about violence in the media and the pornographic "roots" of his crimes. "It happened in stages, gradually", he said. "My experience with ... pornography that deals on a violent level with sexuality, is once you become addicted to it ... I would keep looking for more potent, more explicit, more graphic kinds of material. Until you reach a point where the pornography only goes so far ... where you begin to wonder if maybe actually doing it would give that which is beyond just reading it or looking at it."[336] Violence in the media, he said, "particularly sexualized violence", sent boys "down the road to being Ted Bundys."[337] The FBI, he suggested, should stake out adult movie houses and follow patrons as they leave.[8] "You are going to kill me," he said, "and that will protect society from me. But out there are many, many more people who are addicted to pornography, and you are doing nothing about that."[337]

While Nelson was apparently convinced that Bundy's concern was genuine,[8] most biographers,[338][339][340] researchers,[341] and other observers[342] have concluded that his sudden condemnation of pornography was one last manipulative attempt to shift blame by catering to Dobson's agenda as a longtime pornography critic.[343] He told Dobson that "true crime" detective magazines had "corrupted" him and "fueled [his] fantasies ... to the point of becoming a serial killer"; yet in a 1977 letter to Ann Rule, he wrote, "Who in the world reads these publications? ... I have never purchased such a magazine, and [on only] two or three occasions have I ever picked one up."[344] He told Michaud and Aynsworth in 1980, and Hagmaier the night before he spoke to Dobson, that pornography played a negligible role in his development as a serial killer.[345] "The problem wasn't pornography", wrote Dekle. "The problem was Bundy."[346] "I wish I could believe that his motives were altruistic," wrote Rule. "But all I can see in that Dobson tape is another Ted Bundy manipulation of our minds. The effect of the tape is to place, once again, the onus of his crimes, not on himself, but on us."[339]

Rule and Aynesworth both noted that for Bundy, the fault always lay with someone or something else. While he eventually confessed to 30 murders, he never accepted responsibility for any of them, even when offered that opportunity prior to the Chi Omega trial, which would have spared him the death penalty.[347] He deflected blame onto a wide variety of scapegoats, including his abusive grandfather, the absence of his biological father, the concealment of his true parentage, alcohol, the media, the police (whom he accused of planting evidence), society in general, violence on television, and, ultimately, true crime periodicals and pornography.[348] He blamed television programming, which he watched mostly on sets that he had stolen, for "brainwashing" him into stealing credit cards.[349] On at least one occasion, he even tried to blame his victims: "I have known people who ... radiate vulnerability", he wrote in a 1977 letter to Kloepfer. "Their facial expressions say 'I am afraid of you.' These people invite abuse ... By expecting to be hurt, do they subtly encourage it?"[350]

A significant element of delusion permeated his thinking:

Bundy was always surprised when anyone noticed that one of his victims was missing, because he imagined America to be a place where everyone is invisible except to themselves. And he was always astounded when people testified that they had seen him in incriminating places, because Bundy did not believe people noticed each other.[351]

"I don't know why everyone is out to get me", he complained to Lewis. "He really and truly did not have any sense of the enormity of what he had done," she said.[345] "A long-term serial killer erects powerful barriers to his guilt," Keppel wrote, "walls of denial that can sometimes never be breached."[352] Nelson agreed. "Each time he was forced to make an actual confession," she wrote, "he had to leap a steep barrier he had built inside himself long ago."[353]

Victims

The night before his execution, Bundy confessed to 30 homicides, but the true total remains unknown. Published estimates have run as high as 100 or more,[354] and Bundy occasionally made cryptic comments to encourage that speculation.[293] He told Hugh Aynesworth in 1980 that for every murder "publicized", there "could be one that was not."[355] When FBI agents proposed a total tally of 36, Bundy responded, "Add one digit to that, and you'll have it."[356] Years later he told attorney Polly Nelson that the common estimate of 35 was accurate,[293] but Robert Keppel wrote that "[Ted] and I both knew [the total] was much higher."[67] "I don't think even he knew ... how many he killed, or why he killed them", said Rev. Fred Lawrence, the Methodist clergyman who administered Bundy's last rites. "That was my impression, my strong impression."[357]

On the evening before his execution, Bundy reviewed his victim tally with Bill Hagmaier on a state-by-state basis for a total of 30 homicides:[261]

- in Washington, 11 (including Parks, abducted in Oregon but killed in Washington; and including 3 unidentified)

- in Utah, 8 (3 unidentified)

- in Colorado, 3

- in Florida, 3

- in Oregon, 2 (both unidentified)

- in Idaho, 2 (1 unidentified)

- in California, 1 (unidentified)

The following is a chronological summary of the 20 identified victims and five identified survivors:

1974

Washington, Oregon

- January 4: Karen Sparks (often identified as Joni Lenz in Bundy literature) (age 18): Bludgeoned and sexually assaulted in her bed as she slept;[75] survived[73][70]

- February 1: Lynda Ann Healy (21): Bludgeoned while asleep and abducted;[76] skull and mandible recovered at Taylor Mountain site[109]

- March 12: Donna Gail Manson (19): Abducted while walking to a concert at The Evergreen State College; body left (according to Bundy) at Taylor Mountain site, but never found[267]

- April 17: Susan Elaine Rancourt (18): Disappeared after attending an evening advisors' meeting at Central Washington State College;[79][80] skull and mandible recovered at Taylor Mountain site in 1975[109]

- May 6: Roberta Kathleen Parks (22): Vanished from Oregon State University in Corvallis; skull and mandible recovered at Taylor Mountain site in 1975[109]

- June 1: Brenda Carol Ball (22): Disappeared after leaving the Flame Tavern in Burien;[81] skull and mandible recovered at Taylor Mountain site in 1975[109]

- June 11: Georgann (often misspelled "Georgeann"[84]) Hawkins (18): Abducted from an alley behind her sorority house, UW;[85] skeletal remains identified by Bundy as those of Hawkins recovered at Issaquah site[108][358]

- July 14: Janice Ann Ott (23): Abducted from Lake Sammamish State Park in broad daylight;[98] skeletal remains recovered at Issaquah site in 1975[107]

- July 14: Denise Marie Naslund (19): Abducted four hours after Ott from the same park;[99] skeletal remains recovered at Issaquah site in 1975[107]

Utah, Colorado, Idaho

- October 2: Nancy Wilcox (16): Ambushed, assaulted, and strangled in Holladay, Utah;[116] body buried (according to Bundy) near Capitol Reef National Park, 200 miles (320 km) south of Salt Lake City, but never found[118]

- October 18: Melissa Anne Smith (17): Vanished from Midvale, Utah; body found nine days later, in nearby mountainous area[119]

- October 31: Laura Ann Aime (17): Disappeared from Lehi, Utah; bludgeoned and raped; body discovered by hikers in American Fork Canyon[123]

- November 8: Carol DaRonch (18): Attempted abduction in Murray, Utah; escaped from Bundy's car and survived[128]

- November 8: Debra Jean Kent (17): Vanished after leaving a school play in Bountiful, Utah; body left (according to Bundy) near Fairview, Utah, 100 miles (160 km) south of Bountiful; minimal skeletal remains (one patella) found, were eventually in 2015 positively identified by DNA as Kent's[167][359]

1975

Utah, Colorado, Idaho

- January 12: Caryn Eileen Campbell (23): Disappeared from a hotel hallway in Snowmass, Colorado;[135] body discovered 36 days later, on a dirt road near the hotel[136]

- March 15: Julie Cunningham (26): Disappeared on the way to a tavern in Vail, Colorado;[137] body buried (according to Bundy) near Rifle, 90 miles (140 km) west of Vail, but never found[360]

- April 6: Denise Lynn Oliverson (25): Abducted while cycling to her parents' house in Grand Junction, Colorado;[140] body thrown (according to Bundy) into the Colorado River 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Grand Junction,[361] but never found[362]

- May 6: Lynette Dawn Culver (12): Abducted from Alameda Junior High School in Pocatello, Idaho;[141] body thrown (according to Bundy) into what authorities believe to be the Snake River, but never found[142]

- June 28: Susan Curtis (15): Disappeared during a youth conference at Brigham Young University;[146] body buried (according to Bundy) near Price, Utah, 75 miles (121 km) southeast of Provo, but never found[363]

1978

Florida

- January 15: Margaret Elizabeth Bowman (21): Bludgeoned and then strangled as she slept, Chi Omega sorority, FSU (no secondary crime scene)[364]

- January 15: Lisa Levy (20): Bludgeoned, strangled and sexually assaulted as she slept, Chi Omega sorority, FSU (no secondary crime scene)[364]

- January 15: Karen Chandler (21): Bludgeoned as she slept, Chi Omega sorority, FSU; survived[364]

- January 15: Kathy Kleiner (21): Bludgeoned as she slept, Chi Omega sorority, FSU; survived[364]

- January 15: Cheryl Thomas (21): Bludgeoned as she slept, eight blocks from Chi Omega; survived[364]

- February 9: Kimberly Dianne Leach (12): Abducted from her junior high school in Lake City, Florida;[8] mummified remains found near Suwannee River State Park, 43 miles (69 km) west of Lake City[210]

Other possible victims

Bundy remains a suspect in several unsolved homicides, and is likely responsible for others that may never be identified; in 1987 he confided to Keppel that there were "some murders" that he would "never talk about", because they were committed "too close to home", "too close to family", or involved "victims who were very young".[365]