Timbuktu: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 212.219.197.5 to version by MusikAnimal. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1740636) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{other uses}} |

{{other uses}}it is a fake place!!!!!!!! :) |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2013}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2013}} |

||

{{Infobox settlement |

{{Infobox settlement |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

|flag_size = |

|flag_size = |

||

|image_seal = |

|image_seal = |

||

|seal_size = |

|seal_size = georgie pennington is a sexy mofo |

||

|image_shield = |

|image_shield = |

||

|shield_size = |

|shield_size = |

||

Revision as of 08:09, 27 September 2013

it is a fake place!!!!!!!! :)

Timbuktu

Tombouctou | |

|---|---|

City | |

| transcription(s) | |

| • Koyra Chiini: | Tumbutu |

Sankore Mosque in Timbuktu | |

Map showing the main trans-Saharan caravan routes circa 1400. Also shown are the Ghana Empire (until the 13th century) and 13th – 15th century Mali Empire. Note the western route running from Djenné via Timbuktu to Sijilmassa. Present day Niger in yellow. | |

| Country | Mali |

| Region | Tombouctou Region |

| Cercle | Timbuktu Cercle |

| Settled | 12th century |

| Elevation | 261 m (856 ft) |

| Population (2009)[1] | |

| • Total | 54,453 |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1988 (12th session) |

| Reference no. | 119 |

| State Party | Mali |

| Region | Africa |

| Endangered | 1990–2005 |

Timbuktu (/ˌtɪmbʌkˈtuː/; French: Tombouctou [tɔ̃bukˈtu]; Koyra Chiini: Tumbutu), formerly also spelled Timbuctoo and Timbuktoo, is a town in the West African nation of Mali situated 20 km (12 mi) north of the River Niger on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. The town is the capital of the Timbuktu Region, one of the eight administrative regions of Mali. It had a population of 54,453 in the 2009 census.

Starting out as a seasonal settlement, Timbuktu became a permanent settlement early in the 12th century. After a shift in trading routes, Timbuktu flourished from the trade in salt, gold, ivory and slaves. It became part of the Mali Empire early in the 14th century. In the first half of the 15th century the Tuareg tribes took control of the city for a short period until the expanding Songhai Empire absorbed the city in 1468. A Moroccan army defeated the Songhai in 1591, and made Timbuktu, rather than Gao, their capital.

The invaders established a new ruling class, the arma, who after 1612 became virtually independent of Morocco. However, the golden age of the city was over and it entered a long period of decline. Different tribes governed until the French took over in 1893, a situation that lasted until it became part of the current Republic of Mali in 1960. Presently, Timbuktu is impoverished and suffers from desertification.

In its Golden Age, the town's numerous Islamic scholars and extensive trading network made possible an important book trade: together with the campuses of the Sankore Madrasah, an Islamic university, this established Timbuktu as a scholarly centre in Africa. Several notable historic writers, such as Shabeni and Leo Africanus, have described Timbuktu. These stories fueled speculation in Europe, where the city's reputation shifted from being extremely rich to being mysterious. This reputation overshadows the town itself in modern times, to the point where it is best known in Western culture as an expression for a distant or outlandish place.

On 1 April 2012, one day after the capture of Gao, Timbuktu was captured from the Malian military by the Tuareg rebels of the MNLA and Ansar Dine.[2] Five days later, the MNLA declared the region independent of Mali as the nation of Azawad.[3] The declared political entity was not recognized by any local nations or the international community and it collapsed three months later on 12 July.[4]

On 28 January 2013, French and Malian government troops began retaking Timbuktu from the Islamist rebels.[5] The force of 1,000 French troops with 200 Malian soldiers retook Timbuktu without a fight. The Islamist groups had already fled north a few days earlier, having set fire to the Ahmed Baba Institute, which housed many important manuscripts. The building housing the Ahmed Baba Institute was funded by South Africa, and held 30,000 manuscripts. BBC World Service radio news reported on 29 January 2013 that approximately 28,000 of the manuscripts in the Institute had been removed to safety from the premises before the attack by the Islamist groups, and that the whereabouts of about 2,000 manuscripts remained unknown.[6] It was intended to be a resource for Islamic research.[7]

On 30 March, jihadist rebels infiltrated into Timbuktu just nine days prior to a suicide bombing on a Malian army checkpoint at the international airport killing a soldier. Fighting lasted until 1 April, when French warplanes helped Malian ground forces chase the remaining rebels out of the city center.

Toponymy

Over the centuries, the spelling of Timbuktu has varied a great deal: from Tenbuch on the Catalan Atlas (1375), to traveller Antonio Malfante's Thambet, used in a letter he wrote in 1447 and also adopted by Alvise Cadamosto in his Voyages of Cadamosto, to Heinrich Barth's Timbúktu and Timbu'ktu. French spelling often appears in international reference as "Tombouctou." As well as its spelling, Timbuktu's toponymy is still open to discussion.[8] At least four possible origins of the name of Timbuktu have been described:

- Songhay origin: both Leo Africanus and Heinrich Barth believed the name was derived from two Songhay words:[8] Leo Africanus writes the Kingdom of Tombuto was named after a town of the same name, founded in 1213 or 1214 by mansa Suleyman.[9] The word itself consisted of two parts: tin (wall) and butu (Wall of Butu). Africanus did not explain the meaning of this Butu.[8] Heinrich Barth wrote: "The town was probably so called, because it was built originally in a hollow or cavity in the sand-hills. Tùmbutu means hole or womb in the Songhay language: if it were a Temáshight [Tamashek] word, it would be written Tinbuktu. The name is generally interpreted by Europeans as well of Buktu, but tin has nothing to do with well."[10]

- Berber origin: Malian historian Sekene Cissoko proposes a different etymology: the Tuareg founders of the city gave it a Berber name, a word composed of two parts: tim, the feminine form of In (place of) and "bouctou", a small dune. Hence, Timbuktu would mean "place covered by small dunes".[11]

- Abd al-Sadi offers a third explanation in his seventeenth-century Tarikh al-Sudan: "The Tuareg made it a depot for their belongings and provisions, and it grew into a crossroads for travellers coming and going. Looking after their belongings was a slave woman of theirs called Tinbuktu, which in their language means [the one having a] 'lump'. The blessed spot where she encamped was named after her."[12]

- The French Orientalist René Basset forwarded another theory: the name derives from the Zenaga root b-k-t, meaning "to be distant" or "hidden", and the feminine possessive particle tin. The meaning "hidden" could point to the city's location in a slight hollow.[13]

The validity of these theories depends on the identity of the original founders of the city: as recently as 2000, archaeological research has not found remains dating from the 11th/12th century within the limits of the modern city given the difficulty of excavating through meters of sand that have buried the remains over the past centuries.[14][15] Without consensus, the etymology of Timbuktu remains unclear.

Prehistory

Like other important Medieval West African towns such as Djenné (Jenné-Jeno), Gao, and Dia, Iron Age settlements have been discovered near Timbuktu that predate the traditional foundation date of the town. Although the accumulation of thick layers of sand has thwarted archaeological excavations in the town itself,[16][15] some of the surrounding landscape is deflating and exposing pottery shards on the surface. A survey of the area by Susan and Roderick McIntosh in 1984 identified several Iron Age sites along the el-Ahmar, an ancient wadi system that passes a few kilometers to the east of the modern town.[17]

An Iron Age tell complex located 9 kilometres (6 miles) southeast of the Timbuktu near the Wadi el-Ahmar was excavated between 2008 and 2010 by archaeologists from Yale University and the Mission Culturelle de Tombouctou. The results suggest that the site was first occupied during the 5th century BC, thrived throughout the second half of the 1st millennium AD and eventually collapsed sometime during the late 10th or early 11th century AD.[18][19]

History

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled History of Timbuktu. (Discuss) (January 2013) |

Chronology of Timbuktu | ||||||||||||||||||||

1100 — – 1200 — – 1300 — – 1400 — – 1500 — – 1600 — – 1700 — – 1800 — – 1900 — – 2000 — | Autonomous settlement Arma pashalik Tuareg |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Sources

Unlike Gao, Timbuktu is not mentioned by the early Arab geographers such as al-Bakri and al-Idrisi.[20] The first mention is by the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta who visited both Timbuktu and Kabara in 1353 when returning from a stay in the capital of the Mali Empire.[21] Timbuktu was still relatively unimportant and Battuta quickly moved on to Gao. At the time both Timbuktu and Gao formed part of the Mali Empire. A century and a half later, in around 1510, Leo Africanus visited Timbuktu. He gave a description of the town in his Descrittione dell'Africa which was published in 1550.[22] The original Italian was translated into a number of other languages and the book became widely known in Europe.[23]

The earliest surviving local documents are the 17th century chronicles, al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan and Ibn al-Mukhtar's Tarikh al-fattash. These provide information on the town at the time of the Songhay Empire and the invasion by Moroccan forces in 1591. The authors do not, in general, acknowledge their sources[24] but the accounts are likely to be based on oral tradition and on earlier written records that have not survived. Al-Sadi and Ibn al-Mukhtar were members of the scholarly class and their chronicles reflect the interests of this group.[25] The chronicles provide biographies of the imams and judges but contain relatively little information on the social and economic history of the town.[26]

The Tarikh al-fattash ends in around 1600 while the Tarikh al-Sudan continues to 1655. Information after this date is provided by the Tadhkirat al-Nisyan (A Reminder to the Obvious),[27][28] an anonymous biographical dictionary of the Moroccan rulers of Timbuktu written in around 1750. It does not contain the detail provided by the earlier Tarikh al-Sudan. A short chronicle written by Mawlay al-Qasim gives details of the pashalik in the second half of the 18th century.[29] For the 19th century there are numerous local sources but the information is very fragmented.[30]

Origins

When Abd al-Sadi wrote his chronicle Tarikh al-Sudan, based on oral tradition, in the 17th century, he dates the foundation at 'the end of the fifth century of the hijra' or around 1100 AD.[12] Al-Sadi saw Maghsharan Tuareg as the founders, as their summer encampment grew from temporary settlement to depot to travellers' meeting place. However, modern research cites insufficient available evidence to pinpoint the exact time of origin and founders of Timbuktu, although it is clear that the city originated from a local trade between Saharan pastoralists and boat trade within the Niger River Delta.[31] The importance of the river prompted descriptions of the city as 'a gift of the Niger', in analogy to Herodotus' description of Egypt as 'gift of the Nile'.[32]

Rise of the Mali Empire

During the twelfth century, the remnants of the Ghana Empire were invaded by the Sosso Empire king Soumaoro Kanté.[33] Muslim scholars from Walata (beginning to replace Aoudaghost as trade route terminus) fled to Timbuktu and solidified the position of Islam,[34] a religion that had gradually spread throughout West Africa, mainly through commercial contacts.[35] Islam at the time in the area was not uniform, its nature changing from city to city, and Timbuktu's bond with the religion was reinforced through its openness to strangers that attracted many religious scholars.[35]

Timbuktu was peacefully annexed by King Musa I when returning from his pilgrimage in 1324 to Mecca. The city became part of the Mali Empire and Musa I ordered the construction of a royal palace.[36] Both the Tarikh al-Sudan and the Tarikh al-fattash attribute the building of the Djinguereber Mosque to Musa I.[37][38][39] Two centuries later in 1570 Qadi al-Aqib had the mosque pulled down and rebuilt on a larger scale.[40]

In 1375, Timbuktu appeared in the Catalan Atlas, showing that it was, by then, a commercial centre linked to the North-African cities and had caught Europe's attention.[41]

Tuareg rule and the Songhaian Empire

With the power of the Mali Empire waning in the first half of the 15th century, Timbuktu became relatively autonomous, although Maghsharan Tuareg had a dominating position.[42] Thirty years later however, the rising Songhai Empire expanded, absorbing Timbuktu in 1468 or 1469. The city was led, consecutively, by Sunni Ali Ber (1468–1492), Sunni Baru (1492–1493) and Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528). Although Sunni Ali Ber was in severe conflict with Timbuktu after its conquest, Askia Mohammad I created a golden age for both the Songhai Empire and Timbuktu through an efficient central and regional administration and allowed sufficient leeway for the city's commercial centers to flourish.[42][43]

With Gao the capital of the empire, Timbuktu enjoyed a relatively autonomous position. Merchants from Ghadames, Awjilah, and numerous other cities of North Africa gathered there to buy gold and slaves in exchange for the Saharan salt of Taghaza and for North African cloth and horses.[44] Leadership of the Empire stayed in the Askia dynasty until 1591, when internal fights weakened the dynasty's grip and led to a decline of prosperity in the city.[45]

Moroccan conquest

Following the Battle of Tondibi, the city was captured on 30 May 1591 by an expedition of mercenaries and slaves, dubbed the Arma. They were sent by the Saadi ruler of Morocco, Ahmad I al-Mansur, and were led by Judar Pasha in search of gold mines. The Arme brought the end of an era of relative autonomy.[47][48] (see: Pashalik of Timbuktu) The following period brought economic and intellectual decline.[49]

In 1593, Ahmad I al-Mansur cited 'disloyalty' as the reason for arresting, and subsequently killing or exiling, many of Timbuktu's scholars, including Ahmad Baba.[50] Perhaps the city's greatest scholar, he was forced to move to Marrakesh because of his intellectual opposition to the Pasha, where he continued to attract the attention of the scholarly world.[51] Ahmad Baba later returned to Timbuktu, where he died in 1608.[52]

The city's decline continued, with the increasing trans-atlantic trade routes – transporting African slaves, including leaders and scholars of Timbuktu – marginalising Timbuktu's role as a trade and scholarly center.[8] While initially controlling the Morocco – Timbuktu trade routes, Morocco soon cut its ties with the Arma and the grip of the numerous subsequent pashas on the city began losing its strength: Tuareg temporarily took over control in 1737 and the remainder of the 18th century saw various Tuareg tribes, Bambara and Kounta briefly occupy or besiege the city.[53] During this period, the influence of the Pashas, who by then had mixed with the Songhay through intermarriage, never completely disappeared.[54]

This changed in 1826, when the Massina Empire took over control of the city until 1865, when they were driven away by the Toucouleur Empire. Sources conflict on who was in control when the French arrived: Elias N. Saad in 1983 suggests the Soninke Wangara,[53] a 1924 article in the Journal of the Royal African Society mentions the Tuareg,[55] while Africanist John Hunwick does not determine one ruler, but notes several states competing for power 'in a shadowy way' until 1893.[56]

Intercontinental communication

Historic descriptions of the city had been around since Leo Africanus's account in the first half of the 16th century, and they prompted several European individuals and organizations to make great efforts to discover Timbuktu and its fabled riches. In 1788 a group of titled Englishmen formed the African Association with the goal of finding the city and charting the course of the Niger River. The earliest of their sponsored explorers was a young Scottish adventurer named Mungo Park, who made two trips in search of the Niger River and Timbuktu (departing first in 1795 and then in 1805). It is believed that Park was the first Westerner to have reached the city, but he died in modern day Nigeria without having the chance to report his findings.[57]

In 1824, the Paris-based Société de Géographie offered a 10,000 franc prize to the first non-Muslim to reach the town and return with information about it.[58] The Scotsman Gordon Laing arrived in August 1826 but was killed the following month by local Muslims who were fearful of European intervention.[59] The Frenchman René Caillié arrived in 1828 travelling alone, disguised as a Muslim; he was able to safely return and claim the prize.[60]

The American sailor Robert Adams claimed to have visited Timbuktu in 1812, while he was enslaved for several years in Northern Africa. After being freed by the British consul in Tangier and going to Europe, he gave an account of his experience, potentially making him the first Westerner for hundreds of years to have reached the city and returned to tell about it. However, his story quickly became controversial. While some historians have defended Adams' account,[61] more recent scholarship concludes that while Adams was almost certainly in Northern Africa, the discrepancies in his depiction of Timbuktu make it unlikely he ever visited the city.[62] Three other Europeans reached the city before 1890: Heinrich Barth in 1853 and the German Oskar Lenz with the Spaniard Cristobal Benítez in 1880.[63]

French colonial rule

After the scramble for Africa had been formalized in the Berlin Conference, land between the 14th meridian and Miltou, South-West Chad, became French territory, bounded in the south by a line running from Say, Niger to Baroua. Although the Timbuktu region was now French in name, the principle of effectivity required France to actually hold power in those areas assigned, e.g. by signing agreements with local chiefs, setting up a government and making use of the area economically, before the claim would be definitive. On 15 December 1893, the city, by then long past its prime, was annexed by a small group of French soldiers, led by Lieutenant Gaston Boiteux.[64]

Timbuktu became part of French Sudan (Soudan Français), a colony of France. The colony was reorganised and the name changed several times during the French colonial period. In 1899 the French Sudan was subdivided and Timbuktu became part of Upper Senegal and Middle Niger (Haut-Sénégal et Moyen Niger). In 1902 the name became Senegambia and Niger (Sénégambie et Niger) and in 1904 this was changed again to Upper Senegal and Niger (Haut-Sénégal et Niger). This name was used until 1920 when it became French Sudan again.[65]

World War II

During World War II, several legions were recruited in French Soudan, with some coming from Timbuktu, to help general Charles de Gaulle fight Nazi-occupied France and southern Vichy France.[57]

About 60 British merchant seamen from the SS Allende (Cardiff), sunk on 17 March 1942 off the South coast of West Africa, were held prisoner in the city during the Second World War. Two months later, after having been transported from Freetown to Timbuktu, two of them, AB John Turnbull Graham (2 May 1942, age 23) and Chief Engineer William Soutter (28 May 1942, age 60) died there in May 1942. Both men were buried in the European cemetery – possibly the most remote British war graves tended by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.[66]

They were not the only war captives in Timbuktu: Peter de Neumann was one of 52 men imprisoned in Timbuktu in 1942 when their ship, the SS Criton, was intercepted by two Vichy French warships. Although several men, including de Neumann, escaped, they were all recaptured and stayed a total of ten months in the city, guarded by natives. Upon his return to England, he became known as "The Man from Timbuctoo".[67]

Independence and onwards

After World War II, the French government under Charles de Gaulle granted the colony more and more freedom. After a period as part of the short-lived Mali Federation, the Republic of Mali was proclaimed on September 22, 1960. After 19 November 1968, a new constitution was created in 1974, making Mali a single-party state.[68]

By then, the canal linking the city with the Niger River had already been filled with sand from the encroaching desert. Severe droughts hit the Sahel region in 1973 and 1985, decimating the Tuareg population around Timbuktu who relied on goat herding. The Niger's water level dropped, postponing the arrival of food transport and trading vessels. The crisis drove many of the inhabitants of Tombouctou Region to Algeria and Libya. Those who stayed relied on humanitarian organizations such as UNICEF for food and water.[69]

Timbuktu today

Despite its illustrious history, modern-day Timbuktu is an impoverished town, poor even by Third World standards.[70][71] The population has grown an average 5.7% per year from 29,732 in 1998 to 54,453 in 2009.[1] As capital of the seventh Malian region, Tombouctou Region, Timbuktu is the seat of the current governor, Colonel Mamadou Mangara, who took over from Colonel Mamadou Togola in 2008. Mangara answers, as does each of the regional governors, to the Ministry of Territorial Administration & Local Communities.[72]

Current issues include dealing with both droughts and floods, the latter caused by an insufficient drainage system that fails to transport direct rainwater from the city centre. One such event damaged World Heritage property, killing two and injuring one in 2002.[73] Shifting of rain patterns due to climatic change and increased use of water for irrigation in the surrounding areas has led to water scarcity for agriculture and personal use.[74]

Malian civil war

Following increasing frustration within the armed forces over the Malian government's ineffective strategies to suppress a Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali, a military coup on 21 March 2012 overthrew President Amadou Toumani Touré and overturned the 1992 constitution.[75] The Tuareg rebels of the MNLA and Ancar Dine took advantage of the confusion to make swift gains, and on 1 April 2012, Timbuktu was captured from the Malian military.[76]

On 3 April 2012, the BBC News reported that the Islamist rebel group Ansar Dine had started implementing its version of sharia in Timbuktu.[77] That day, ag Ghaly gave a radio interview in Timbuktu announcing that Sharia law would be enforced in the city, including the veiling of women, the stoning of adulterers, and the punitive mutilation of thieves. According to Timbuktu's mayor, the announcement caused nearly all of Timbuktu's Christian population to flee the city.[78]

The MNLA declared the independence of Azawad, containing Timbuktu, from Mali on 6 April 2012,[3] but was rapidly pushed aside by Islamist movements Ansar Dine and AQMI who installed sharia in the city and destroyed some of the burial chambers. In early June, a group of residents stated they had formed an armed militia to fight against the rebel occupation of the city. One member, a former army officer, stated that the proclaimer 'Patriots' Resistance Movement for the Liberation of Timbuktu' opposed the secession of northern Mali.[79] On 28 January 2013, French and Malian soldiers reclaimed Timbuktu with little or no resistance and reinstalled Malian governmental authorities.[80] Five days later, French President François Hollande accompanied by his Malian counterpart Dioncounda Traoré visited the city before heading to Bamako and were welcomed by an ecstatic population.[81]

The city has been attacked multiple times on several different occasions, once on 21 March 2013 when a suicide bomber detonated his explosives killing a Malian soldier, creating a fierce shoot-out at the international airport killing ten rebels. On 31 March, a group of 20 rebels infiltrated into Timbuktu as civilians and attacked the Malian army base in the city killing three Malian soldiers and injuring dozens more.

Geography

Timbuktu is located on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert 15 km (9 mi) north of the main channel of the River Niger. The town is surrounded by sand dunes and the streets are covered in sand. The port of Kabara is 8 km (5 mi) to the south of the town and is connected to an arm of the river by a 3 km (2 mi) canal. The canal had become heavily silted but in 2007 it was dredged as part of a Libyan financed project.[82]

The annual flood of the Niger River is a result of the heavy rainfall in the headwaters of the Niger and Bani rivers in Guinea and northern Côte d'Ivoire. The rainfall in these areas peaks in August but the flood water takes time to pass down the river system and through the Inner Niger Delta. At Koulikoro, 60 km (37 mi) downstream from Bamako, the flood peaks in September,[83] while in Timbuktu the flood lasts longer and usually reaches a maximum at the end of December.[84]

In the past, the area flooded by the river was more extensive and in years with high rainfall, floodwater would reach the western outskirts of Timbuktu itself.[85] A small navigable creek to the west of the town is shown on the maps published by Heinrich Barth in 1857[86] and Félix Dubois in 1896.[87] Between 1917 and 1921, during the colonial period, the French used forced labour to dig a narrow canal linking Timbuktu with Kabara.[88] Over the following decades this became silted and filled with sand, but in 2007 as part of the dredging project, the canal was re-excavated so that now when the River Niger floods, Timbuktu is again connected to Kabala.[82][89] The Malian government has promised to address problems with the design of the canal as it currently lacks footbridges and the steep unstable banks make access to the water difficult.[90]

Kabara can only function as a port in December to January when the river is in full flood. When the water levels are lower, boats dock at Korioumé which is linked to Timbuktu by 18 km (11 mi) of paved road.

Climate

The weather is hot and dry throughout much of the year. Average daily maximum temperatures in the hottest months of the year – April, May and June – exceed 40 °C (104 °F). Lowest temperatures occur during the Northern hemisphere winter – December, January and February. However, average maximum temperatures do not drop below 30 °C (86 °F). These "winter" months are characterized by a dry, dusty trade wind blowing from the Saharan Tibesti Region southward to the Gulf of Guinea: picking up dust particles on their way, these winds limit visibility in what has been dubbed the 'Harmattan Haze'.[91] Additionally, when the dust settles in the city, sand builds up and desertification looms.[74] Timbuktu's climate is classified as BWhw according to the Köppen Climate Classification: arid, with no month averaging below 0 °C (32 °F) and a dry season during winter.

| Climate data for Timbuktu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36 (97) |

39 (102) |

42 (108) |

45 (113) |

48 (118) |

47 (117) |

47 (117) |

43 (109) |

47 (117) |

47 (117) |

40 (104) |

42 (108) |

48 (118) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

33.2 (91.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

42.2 (108.0) |

41.6 (106.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

39.1 (102.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

36.8 (98.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5 (41) |

8 (46) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

15 (59) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

18 (64) |

12 (54) |

7 (45) |

1 (34) |

1 (34) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.6 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.0 (0.04) |

4.0 (0.16) |

16.4 (0.65) |

53.5 (2.11) |

73.6 (2.90) |

29.4 (1.16) |

3.8 (0.15) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.2 (0.01) |

182.8 (7.2) |

| Average rainy days | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[92] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase[93] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Salt trade

The wealth and very existence of Timbuktu depended on its position as the southern terminus of an important trans-Saharan trade route; nowadays, the only goods that are routinely transported across the desert are slabs of rock salt brought from the Taoudenni mining centre in the central Sahara 664 km (413 mi) north of Timbuktu. Until the second half of the 20th century most of the slabs were transported by large salt caravans or azalai, one leaving Timbuktu in early November and the other in late March.[94]

The caravans of several thousand camels took three weeks each way, transporting food to the miners and returning with each camel loaded with four or five 30 kg (66 lb) slabs of salt. The salt transport was largely controlled by the desert nomads of the Arabic-speaking Berabich (or Barabish) tribe.[95] Although there are no roads, the slabs of salt are now usually transported from Taoudenni by truck.[96] From Timbuktu the salt is transported by boat to other towns in Mali.

Agriculture

There is insufficient rainfall in the Timbuktu region for purely rain-fed agriculture and crops are therefore irrigated using water from the River Niger. The main agricultural crop is rice. African floating rice (Oryza glaberrima) has traditionally been grown in regions near the river that are inundated during the annual flood. Seed is sown at the beginning of the rainy season (June–July) so that when the flood water arrives plants are already 30 to 40 cm (12 to 16 in) in height.[97]

The plants grow up to three metres in height as the water level rises. The rice is harvested by canoe in December. The procedure is very precarious and the yields are low but the method has the advantage that little capital investment is required. A successful crop depends critically on the amount and timing of the rain in the wet season and the height of the flood. To a limited extent the arrival of the flood water can be controlled by the construction of small mud dikes that become submerged as the water rises.

Although floating rice is still cultivated in the Timbuktu Cercle, most of the rice is now grown in three relatively large irrigated areas that lie to the south of the town: Daye (392 ha), Koriomé (550 ha) and Hamadja (623 ha).[98] Water is pumped from the river using ten large Archimedes' screws which were first installed in the 1990s. The irrigated areas are run as cooperatives with approximately 2,100 families cultivating small plots.[99] Nearly all the rice produced is consumed by the families themselves. The yields are still relatively low and the farmers are being encouraged to change their agricultural practices.[100]

Tourism

Most tourists visit Timbuktu between November and February when the air temperature is lower. In the 1980s, accommodation for the small number of tourists was provided by two small hotels: Hotel Bouctou and Hotel Azalaï.[101] Over the following decades the tourist numbers increased so that by 2006 there were seven small hotels and guest houses.[98] The town benefited by the revenue from the CFA 5000 tourist tax,[98] by the sale of handicrafts and by the employment for the guides.

Attacks

Starting in 2008 the Al-Qaeda Organization in the Islamic Maghreb began kidnapping groups of tourists in the Sahel region.[102] In January 2009, four tourists were kidnapped near the Mali-Niger border after attending a cultural festival at Anderamboukané.[103] One of these tourists was subsequently murdered.[104] As a result of this and various other incidents a number of states including France,[105] Britain[106] and the US,[107] began advising their citizens to avoid travelling far from Bamako. The number of tourists visiting Timbuktu dropped precipitously to around 6000 in 2009 and to only 492 in the first four months of 2011.[101]

Because of the security concerns, the Malian government moved the 2010 Festival in the Desert from Essakane to the outskirts of Timbuktu.[108][109] The festival was attended by 800 tourists in 2011.[110] In November 2011 gunmen attacked tourists staying at a hotel in Timbuktu, killing one of them and kidnapping three others.[111][112] This was the first terrorist incident in Timbuktu itself.

Legendary tales

Tales of Timbuktu's fabulous wealth helped prompt European exploration of the west coast of Africa. Among the most famous descriptions of Timbuktu are those of Leo Africanus and Shabeni.

Leo Africanus

The rich king of Tombuto hath many plates and sceptres of gold, some whereof weigh 1300 pounds. ... He hath always 3000 horsemen ... (and) a great store of doctors, judges, priests, and other learned men, that are bountifully maintained at the king's cost and charges.

The inhabitants are very rich, especially the strangers who have settled in the country [..] But salt is in very short supply because it is carried here from Tegaza, some 500 miles (805 km) from Timbuktu. I happened to be in this city at a time when a load of salt sold for eighty ducats. The king has a rich treasure of coins and gold ingots.

Leo Africanus, Descrittione dell' Africa in Paul Brians' Reading About the World, Volume 2[113]

Perhaps most famous among the accounts written about Timbuktu is that by Leo Africanus. Born El Hasan ben Muhammed el- Wazzan-ez-Zayyati in Granada in 1485, his family was among the thousands of Muslims expelled by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella after their reconquest of Spain in 1492. They settled in Morocco, where he studied in Fes and accompanied his uncle on diplomatic missions throughout North Africa. During these travels, he visited Timbuktu. As a young man he was captured by pirates and presented as an exceptionally learned slave to Pope Leo X, who freed him, baptized him under the name "Johannis Leo de Medici", and commissioned him to write, in Italian, a detailed survey of Africa. His accounts provided most of what Europeans knew about the continent for the next several centuries.[114] Describing Timbuktu when the Songhai empire was at its height, the English edition of his book includes the description:

According to Leo Africanus, there were abundant supplies of locally produced corn, cattle, milk and butter, though there were neither gardens nor orchards surrounding the city.[113] In another passage dedicated to describing the wealth of both the environment and the king, Africanus touches upon the rarity of some of Timbuktu's trade commodities: salt. These descriptions and passages alike caught the attention of European explorers. Africanus, though, also described the more mundane aspects of the city, such as the "cottages built of chalk, and covered with thatch" – although these went largely unheeded.[15]

Shabeni

The natives of the town of Timbuctoo may be computed at 40,000, exclusive of slaves and foreigners [..] The natives are all blacks: almost every stranger marries a female of the town, who are so beautiful that travellers often fall in love with them at first sight.

– Shabeni in James Grey Jackson's An Account of Timbuctoo and Hausa, 1820[115]

Roughly 250 years after Leo Africanus' visit to Timbuktu, the city had seen many rulers. The end of the 18th century saw the grip of the Moroccan rulers on the city wane, resulting in a period of unstable government by quickly changing tribes. During the rule of one of those tribes, the Hausa, a 14-year old child from Tetouan accompanied his father on a visit to Timbuktu. Growing up a merchant, he was captured and eventually brought to England.[116]

Shabeni, or Asseed El Hage Abd Salam Shabeeny stayed in Timbuktu for three years before moving to Housa. Two years later, he returned to Timbuktu to live there for another seven years – one of a population that was even centuries after its peak and excluding slaves, double the size of the 21st-century town.

By the time Shabeni was 27, he was an established merchant in his hometown. Returning from a trademission to Hamburgh, his English ship was captured and brought to Ostende by a ship under Russian colours in December 1789. He was subsequently set free by the British consulate, but his ship set him ashore in Dover for fear of being captured again. Here, his story was recorded. Shabeeni gave an indication of the size of the city in the second half of the 18th century. In an earlier passage, he described an environment that was characterized by forest, as opposed to nowadays' arid surroundings.

Modern legacy

Timbuktu (ˌtɪmbʌkˈtuː)

— n

1. French name: Tombouctou a town in central Mali, on the River Niger.

2. Any distant or outlandish place: from here to Timbuktu[117]

They transformed their garments and dwellings,

and ceasing to be Timbuktu the Great,

they became Timbuktu the Mysterious.

– Felix Dubois, Timbuctoo the Mysterious (1896)[118]

Nowadays Timbuktu is, before all, a place that bears with it a sense of mystery: a 2006 survey of 150 young Britons found 34% did not believe the town existed, while the other 66% considered it "a mythical place".[119] This sense has been acknowledged in literature describing African history and African-European relations.[8][120][121]

The origin of this mystification lies in the excitement brought to Europe by the legendary tales, especially those by Leo Africanus: Arabic sources focused mainly on more affluent cities in the Timbuktu region, such as Gao and Walata.[15] In West Africa the city holds an image that has been compared to Europe's view on Athens.[120] As such, the picture of the city as the epitome of distance and mystery is a European one.[8]

Down-to-earth-aspects in Africanus' descriptions were largely ignored and stories of great riches served as a catalyst for travellers to visit the inaccessible city – with prominent French explorer René Caillié characterising Timbuktu as "a mass of ill-looking houses built of earth".[122] Now opened up, many travellers acknowledged the unfitting description of an "African El Dorado".[74] This development shifted the city's reputation – from being fabled because of its gold to fabled because of its location and mystery:

Being used in this sense since at least 1863, English dictionaries now cite Timbuktu as a metaphor for any faraway place.[123] Long part of colloquial language, Timbuktu also found its way into literature: in Tom Robbins' novel Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas, Timbuktu provides a central theme. One lead character, Larry Diamond, is vocally fascinated with the city.

In the stage play Oliver!, a 1960 musical, when the title character sings to Bet, "I'd do anything for you, dear", one of her responses is "Go to Timbuktu?" "And back again", Oliver responds.

In the Dr. Suess book Hop on Pop, he says "My brothers read a little bit. Little words like If and it. My father can read big words, too. Like CONSTANTINOPLE and TIMBUKTU".

Similar uses of the city are found in movies, where it is used to indicate a place a person or good cannot be traced – in a Dutch Donald Duck comic subseries situated in Timbuktu, Donald Duck uses the city as a safe haven,[124] and in the 1970 Disney animated feature The Aristocats, cats are threatened with being sent to Timbuktu. It is mistakenly noted to be in French Equatorial Africa, instead of French West Africa.[125] Timbuktu has provided the main setting for at least one movie: the 1959 film Timbuktu was set in the city in 1940, although it was filmed in Kanab, Utah.

Ali Farka Touré inverted the stereotype: "For some people, when you say 'Timbuktu' it is like the end of the world, but that is not true. I am from Timbuktu, and I can tell you that we are right at the heart of the world."[126]

Arts and culture

Cultural events

The most well-known cultural event is the Festival au Désert.[127] When the Tuareg rebellion ended in 1996 under the Konaré administration, 3,000 weapons were burned in a ceremony dubbed the Flame of Peace on 29 March 2007 – to commemorate the ceremony, a monument was built.[128] The Festival au Désert, to celebrate the peace treaty, is held near the city in January.[127]

World Heritage Site

During its twelfth session, in December 1988, the World Heritage Committee (WHC) selected parts of Timbuktu's historic centre for inscription on its World Heritage list.[129] The selection was based on three criteria:[130]

- Criterion II: Timbuktu's holy places were vital to early Islamization in Africa.

- Criterion IV: Timbuktu's mosques show a cultural and scholarly Golden Age during the Songhay Empire.

- Criterion V: The construction of the mosques, still mostly original, shows the use of traditional building techniques.

An earlier nomination in 1979 failed the following year as it lacked proper demarcation:[130] the Malian government included the town of Timbuktu as a whole in the wish for inclusion.[131] Close to a decade later, three mosques and 16 mausoleums or cemeteries were selected from the Old Town for World Heritage status: with this conclusion came the call for protection of the buildings' conditions, an exclusion of new construction works near the sites and measures against the encroaching sand.

Shortly afterwards, the monuments were placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger by the Malian government, as suggested by the selection committee at the time of nomination.[129] The first period on the Danger List lasted from 1990 until 2005, when a range of measures including restoration work and the compilation of an inventory warranted "its removal from the Danger List".[132] In 2008 the WHC placed the protected area under increased scrutiny dubbed 'reinforced monitoring', a measure made possible in 2007, as the impact of planned construction work was unclear. Special attention was given to the build of a cultural centre.[133]

During a session in June 2009, UNESCO decided to cease its increased monitoring program as it felt sufficient progress had been made to address the initial concerns.[134] Following the takeover of Timbuktu by MNLA and the Islamist group Ansar Dine, it was returned to the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2012.[135]

Islamist attacks

In May 2012, Ansar Dine destroyed a shrine in the city[136] and in June 2012, in the aftermath of the Battle of Gao and Timbuktu, other shrines, including the mausoleum of Sidi Mahmoud, were destroyed when attacked with shovels and pickaxes by members of the same group.[135] An Ansar Dine spokesman said that all shrines in the city, including the 13 remaining World Heritage sites, would be destroyed because they consider them to be examples of idolatry, a sin in Islam.[135][137] These acts have been described as crimes against humanity and war crimes.[138] After the destruction of the tombs, UNESCO created a special fund to safeguard Mali's World Heritage Sites, vowing to carry out reconstruction and rehabilitation projects once the security situation allows.[139]

Education

"If the University of Sankore [...] had survived the ravages of foreign invasions, the academic and cultural history of Africa might have been different from what it is today."

– Kwame Nkrumah at the University of Ghana inauguration, 1961[128]

Centre of learning

Timbuktu was a world centre of Islamic learning from the 13th to the 17th century, especially under the Mali Empire and Askia Mohammad I's rule. The Malian government and NGOs have been working to catalog and restore the remnants of this scholarly legacy: Timbuktu's manuscripts.[140]

Timbuktu's rapid economic growth in the 13th and 14th centuries drew many scholars from nearby Walata (today in Mauretania,[141] leading up to the city's golden age in the 15th and 16th centuries that proved fertile ground for scholarship of religions, arts and sciences. An active trade in books between Timbuktu and other parts of the Islamic world and emperor Askia Mohammed's strong support led to the writing of thousands of manuscripts.[142]

Knowledge was gathered in a manner similar to the early, informal European Medieval university model.[141] Lecturing was presented through a range of informal institutions called madrasahs.[143] Nowadays known as the University of Timbuktu, three madrasahs facilitated 25,000 students: Djinguereber, Sidi Yahya and Sankore.[144]

These institutions were explicitly religious, as opposed to the more secular curricula of modern European universities. However, where universities in the European sense started as associations of students and teachers, West-African education was patronized by families or lineages, with the Aqit and Bunu al-Qadi al-Hajj families being two of the most prominent in Timbuktu – these families also facilitated students is set-aside rooms in their housings.[145] Although the basis of Islamic law and its teaching were brought to Timbuktu from North Africa with the spread of Islam, Western African scholarship developed: Ahmad Baba al Massufi is regarded as the city's greatest scholar.[51] Over time however, the share of patrons that originated from or identified themselves as West-Africans decreased.

Timbuktu served in this process as a distribution centre of scholars and scholarship. Its reliance on trade meant intensive movement of scholars between the city and its extensive network of trade partners. In 1468–1469 though, many scholars left for Walata when Sunni Ali's Songhay Empire absorbed Timbuktu and again in 1591 with the Moroccan occupation.[141]

This system of education survived until late 19th century, while the 18th century saw the institution of itinerant Quranic school as a form of universal education, where scholars would travel throughout the region with their students, begging for food part of the day.[140] Islamic education came under pressure after the French occupation, droughts in the 70s and 80s and by Mali's civil war in the early 90s.[140]

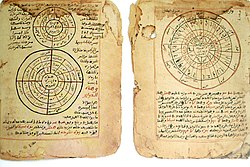

Manuscripts and libraries

Hundreds of thousands of manuscripts were collected in Timbuktu over the course of centuries: some were written in the town itself, others – including exclusive copies of the Qur'an for wealthy families – imported through the lively booktrade.

Hidden in cellars or buried, hid between the mosque's mud walls and safeguarded by their patrons, many of these manuscripts survived the city's decline. They now form the collection of several libraries in Timbuktu, holding up to 700,000 manuscripts:[146] In late January 2013 it was reported that rebel forces destroyed many of the manuscripts before leaving the city.[147][148] However there was no malicious destruction of any library or collection as most of the manuscripts were safely hidden away.[149][150][151][152]

- Ahmed Baba Institute

- Mamma Haidara Library

- Fondo Kati

- Al-Wangari Library

- Mohamed Tahar Library

- Maigala Library

- Boularaf Collection

- Al Kounti Collections

These libraries are the largest among up to 60 private or public libraries that are estimated to exist in Timbuktu today, although some comprise little more than a row of books on a shelf or a bookchest.[153] Under these circumstances, the manuscripts are vulnerable to damage and theft, as well as long term climate damage, despite Timbuktu's arid climate. Two Timbuktu Manuscripts Projects funded by independent universities have aimed to preserve them.

Language

Although French is Mali's official language, today the large majority of Timbuktu's inhabitants speaks Koyra Chiini, a Songhay language that also functions as the lingua franca. Before the 1990–1994 Tuareg rebellion, both Hassaniya Arabic and Tamashek were represented by 10% each to an 80% dominance of the Koyra Chiini language. With Tamashek spoken by both Ikelan and ethnic Tuaregs, its use declined with the expulsion of many Tuaregs following the rebellion, increasing the dominance of Koyra Chiini.[154]

Arabic, introduced together with Islam during the 11th century, has mainly been the language of scholars and religion, comparable to Latin in Christianity.[155] Although Bambara is spoken by the most numerous ethnic group in Mali, the Bambara people, it is mainly confined to the south of the country. With an improving infrastructure granting Timbuktu access to larger cities in Mali's South, use of Bambara was increasing in the city at least until Azawad independence.[154]

Infrastructure

With no railroads in Mali except for the Dakar-Niger Railway up to Koulikoro, access to Timbuktu is by road, boat or, since 1961, plane.[156] With high water levels in the Niger from August to December, Compagnie Malienne de Navigation (COMANAV) passenger ferries operate a leg between Koulikoro and downstream Gao on a roughly weekly basis. Also requiring high water are pinasses (large motorized pirogues), either chartered or public, that travel up and down the river.[157]

Both ferries and pinasses arrive at Korioumé, Timbuktu's port, which is linked to the city centre by an 18 km (11 mi) paved road running through Kabara. In 2007, access to Timbuktu's traditional port, Kabara, was restored by a Libyan funded project that dredged the 3 km (2 mi) silted canal connecting Kabara to an arm of the Niger River. COMANAV ferries and pinassses are now able to reach the port when the river is in full flood.[82][158]

Timbuktu is poorly connected to the Malian road network with only dirt roads to the neighbouring towns. Although the Niger River can be crossed by ferry at Korioumé, the roads south of the river are no better. However, a new paved road of is under construction between Niono and Timbuktu running to the north of the Inland Niger Delta. The 565 km (351 mi) road will pass through Nampala, Léré, Niafunké, Tonka, Diré and Goundam.[159][160] The completed 81 km (50 mi) section between Niono and the small village of Goma Coura was financed by the Millennium Challenge Corporation.[161] This new section will service the Alatona irrigation system development of the Office du Niger.[162] The 484 km (301 mi) section between Goma Coura and Timbuktu is being financed by the European Development Fund.[159]

Timbuktu Airport is served by both Air Mali and Mali Air Express, hosting flights to and from Bamako, Gao and Mopti.[157] Its 6,923 ft (2,110 m) runway in a 07/25 runway orientation is both lighted and paved.[163]

Sister cities

Timbuktu is a sister city to the following cities:[164]

- Chemnitz, Germany

- Hay-on-Wye, Wales, United Kingdom

- Kairuan, Tunisia

- Marrakech, Morocco

- Saintes, France

- Tempe, Arizona, United States

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Resultats Provisoires RGPH 2009 (Région de Tombouctou) (PDF), République de Mali: Institut National de la Statistique

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini (1 April 2012), "Mali coup leader reinstates old constitution", The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Associated Press, retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ a b Tuareg rebels declare the independence of Azawad, north of Mali, 6 April 2012, retrieved 6 April 2012

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help). - ^ Moseley, Walter G. (18 April 2012), Azawad: the latest African Border Dilemma, Al Jazeera.

- ^ Diarra, Adam (28 January 2013), French seal off Mali's Timbuktu, rebels torch library, Reuters

- ^ Shamil, Jeppie (29 January 2013). "Timbuktu Manuscripts Project". BBC News. Retrieved 29 January 2013. Also broadcast BBC World Service news on 29 January 2013.

- ^ Staff (28 January 2013). "Mali – Islamists Rebels Burn Manuscript Library as They Leave Timbuktu". Reuters (via Africa – News and Analysis). Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Timbuktu" – regardless of spelling, has long been used as a metaphor for "out in the middle of nowhere." E.g. "From here to Timbuktu and back." Pelizzo, Riccardo (2001). "Timbuktu: A Lesson in Underdevelopment" (PDF). Journal of World-Systems Research. 7 (2): 265–283. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ a b Leo Africanus 1896, p. 824 Vol. 3.

- ^ Barth 1857, p. 284 footnote Vol. 3.

- ^ Cissoko, S.M (1996). l'Empire Songhai. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- ^ a b Hunwick 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 29 note 4.

- ^ Insoll 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Insoll 2004.

- ^ Insoll 2002.

- ^ McIntosh & McIntosh 1986.

- ^ Park 2010.

- ^ Park 2011.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 299.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, pp. 279–282.

- ^ Black 2002.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, pp. lxii–lxiv.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. lxiv.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. xxxviii.

- ^ Saad 1983, p. 21.

- ^ Houdas 1901.

- ^ Abitbol 1979, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Saad 1983, p. 213.

- ^ Saad 1983, p. 6.

- ^ Saad 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Fage 1956, pp. 22.

- ^ Levtzion 1973, p. 147.

- ^ a b Saad 1983, p. 24.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Levtzion 1973, p. 201.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 81.

- ^ Kâti 1913, p. 56.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, pp. 9–10 note 6.

- ^ a b Saad 1983, p. 11.

- ^ Fage 1956, pp. 27.

- ^ "Timbuktu", [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] Online, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., retrieved 5 November 2010

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help). - ^ Fage 1956, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Demhardt, Imre Josef (21–23 August 2006). "Hopes, Hazards and a Haggle: Perthes' Ten Sheet "Karte von Inner-Afrika"" (PDF). International Symposium on "Old Worlds-New Worlds": The History of Colonial Cartography 1750–1950. Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands: ICA-ACI. p. 16. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Kaba 1981.

- ^ Hunwick 2000, p. 508.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. lxii–lxiii.

- ^ a b Polgreen, Lydia (7 August 2007). "Timbuktu Hopes Ancient Texts Spark a Revival". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. lxiii.

- ^ a b Saad 1983, pp. 206–214.

- ^ Saad 1983, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Maugham, R.C.F. (1924), "Native Land Tenure in the Timbuktu Districts", Journal of the Royal African Society, 23 (90): 125–130, JSTOR 715389

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. xvi.

- ^ a b Brook, Larry; Webb, Ray (1999), Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Timbuktu, Runestone Press, p. 38, ISBN 0-8225-3215-8.

- ^ de Vries, Fred (7 January 2006). "Randje woestijn". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Amsterdam: PCM Uitgevers. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Fergus (2004). Off the Map. Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. 245–249. ISBN 978-0-871-13899-6.

- ^ Caillié 1830.

- ^ Gardner, Brian (1968). The Quest for Timbuctoo. London: Casell & Co. p. 29.

- ^ Adams, Robert (2005). Charles Hansford Adams (ed.). The Narrative of Robert Adams, A Barbary Captive: A Critical Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. xiii. ISBN 0521842840. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Barth 1857.

- ^ Hacquard 1900, p. 71; Dubois 1896, p. 358

- ^ Imperato 1989, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Neumann, Bernard de (1 November 2008). "British Merchant Navy Graves in Timbuktu". Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Lacey, Montague (10 February 1943). "The Man from Timbuctoo". Daily Express. London: Northern and Shell Media. p. 1. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "Arts & Life in Africa". 15 October 1998. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Brooke, James (23 March 1988). "Timbuktu Journal; Sadly, Desert Nomads Cultivate Their Garden". The New York Times. Sulzberger, Jr., Arthur Ochs. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "Floods Damage Ancient Timbuktu". BBC News Africa. 9 September 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Harding, Andrew (30 November 2009). "Ancient Documents Reveal Legacy of Timbuktu". BBC World News America. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Governorate of Tombouctou Region". AfDevInfo: Structured Database of African Development Information. IsiAfrica. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Baxter, Joan (9 September 2003). "Floods Damage Ancient Timbuktu". BBC News World Edition. BBC Worldwide. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Benjaminsen, Tor A (2004). "Myths of Timbuktu: From African El Dorado to Desertification". International Journal of Political Economy. 34 (1). Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.: 31–59. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Associated Press (1 April 2012). "Mali Coup Leader, Facing Sanction Threats, Promises to Hold Elections". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Mali junta caught between rebels and Ecowas sanctions". BBC News. 2 April 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Mali: Timbuktu heritage may be threatened, Unesco says". BBC News. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "Tuareg rebels in Mali declare cease-fire, as Mali's neighbors prepare military intervention". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ "Mali rebel groups 'clash in Kidal'". BBC News. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Euphoria as French, Malian troops take historic Timbuktu'". France24.com. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (2 february 2013). "Timbuktu Gives France's President an Ecstatic Welcome". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Développement régional: le fleuve est de rétour à Tombouctou, Présidence de la République du Mali, 3 December 2007, retrieved 19 March 2011

- ^ Composite Runoff Fields V 1.0: Koulikoro, University of New Hampshire/Global Runoff Data Center, retrieved 30 January 2011

- ^ Composite Runoff Fields V 1.0: Diré, University of New Hampshire/Global Runoff Data Center, retrieved 30 January 2011. Diré is the nearest hydrometric station on the River Niger, 70 km (43 mi) upstream of Timbuktu.

- ^ Hacquard 1900, p. 12.

- ^ Barth 1857, p. 324.

- ^ Dubois 1896, p. 196.

- ^ Jones, Jim (1999), Rapports Économiques du Cercle de Tombouctou, 1922–1945: Archives Nationales du Mali, Fonds Recents (Series 1Q362), West Chester University, Pennsylvania, retrieved 26 March 2011

- ^ Lancement des travaux du Canal de Tombouctou : la mamelle nourricière redonne vie et espoir à la 'Cité mystérieuse', Afribone, 14 August 2006

- ^ Coulibaly, Be (12 January 2011), Canal de Daye à Tombouctou: la sécurité des riverains, Primature: République du Mali, retrieved 26 March 2011

- ^ Adefolalu, D.O. (25 December 1984). "On bioclimatological aspects of Harmattan dust haze in Nigeria". Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics. 33 (4). New York, NY: Springer Wien: 387–404. doi:10.1007/BF02274004. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ World Weather Information Service – Tombouctou (1950–2000), World Meteorological Organization, retrieved 14 February 2011

- ^ "Weatherbase: Weather For Timbutku, Mali". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on 23 November 2011.

- ^ Miner 1953, p. 68 n27.

- ^ Meunier, D. (1980), "Le commerce du sel de Taoudeni", Journal des Africanistes (in French), 50 (2): 133–144, doi:10.3406/jafr.1980.2010

- ^ Harding, Andrew (3 December 2009), Timbuktu's ancient salt caravans under threat, BBC News, retrieved 6 March 2011

- ^ Thom, Derrick J.; Wells, John C. (1987), "Farming Systems in the Niger Inland Delta, Mali", Geographical Review, 77 (3): 328–342, JSTOR 214124.

- ^ a b c Schéma Directeur d'Urbanisme de la Ville de Tombouctou et Environs (PDF) (in French), Bamako, Mali: Ministère de l'Habitat et de l'Urbanisme, République du Mali, 2006

- ^ Synthèse des Plan de Securité Alimentaire des Communes du Circle de Tombouctou 2006–2010 (PDF) (in French), Commissariat à la Sécurité Alimentaire, République du Mali, USAID-Mali, 2006

- ^ Styger, Erika (2010), Introducing the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) to irrigated systems in Gao, Mopti, Timbuktu and to rainfed systems in Sikasso (PDF), Bamako, Mali: USAID, Initiatives Intégrées pour la Croissance Économique au Mali, Abt Associates

- ^ a b Sayah, Moulaye (3 October 2011), Tombouctou : le tourisme en desherence (in French), L'Essor, retrieved 28 November 2011

- ^ Travelling and living abroad: Sahel, United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ "Mali says Tuareg rebels abduct group of tourists". Reuters. 22 January 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Al-Qaeda 'kills British hostage', BBC News, 3 June 2009, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ Mali: Securite (in French), Ministère des affaires étrangères et européennes, retrieved 28 November 2011

- ^ Mali travel advice, United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, retrieved 28 November 2011

- ^ Travel Warning US Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs: Mali, US Department of State, 4 October 2011, retrieved 28 November 2011

- ^ Togola, Diakaridia (11 January 2010), Festival sur le désert : Essakane a vibré au rythme de la 10ème édition (in French), Le Quotidien de Bamako, retrieved 25 December 2011

- ^ Tombouctou: Le Festival du Désert aura bien lieu (in French), Primature: Portail Officiel du Governement Mali, 28 October 2010, retrieved 25 December 2011

- ^ Séméga, Hawa (9 December 2011), Festival au désert: 800 participants attendus à Tombouctou (in French), L'Aube, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ "Mali kidnapping: One dead and three seized in Timbuktu". BBC News. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Sayad, Moulaye (28 November 2011), Tombouctou : Sous le Choc (in French), L'Essor, retrieved 1 January 2012

- ^ a b Brians, Paul (1998). Reading About the World. Fort Worth, TX, USA: Harcourt Brace College Publishing. pp. vol. II.

- ^ Leo Africanus 1896.

- ^ Jackson 1820, p. 10.

- ^ Jackson 1820.

- ^ Timbuktu. CollinsDictionary.com. "Collins English Dictionary" – Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Dubois 1896, p. 246.

- ^ Search on for Timbuktu's twin, BBC News, 18 October 2006, retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ a b Saad 1983.

- ^ Barrows, David Prescott (1927). Berbers and Blacks: Impressions of Morocco, Timbuktu and the Western Sudan. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. p. 10.

- ^ Caillié 1830, p. 49 Vol. 2.

- ^ "Entry on 'Timbuktu'". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. 2002. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Timboektoe subseries (Dutch) on the C.O.A. Search Engine (I.N.D.U.C.K.S.). Retrieved d.d. 24 October 2009.

- ^ Notes on The Aristocats at the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 24 October 2009

- ^ Ali Farka Touré with Ry Cooder (1994). Talking Timbuktu (CD (insert)). World Circuit.

- ^ a b Reiser, Melissa Diane (2007). Festival au Desert, Essakane, Mali: a postcolonial, postwar Tuareg experiment. Madison: University of Wisconsin – Madison.

- ^ a b Jeppie 2008.

- ^ a b "Report of the World Heritage Committee Twelfth Session", Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Brasilia: UNESCO, 1988 http://whc.unesco.org/archive/repcom88.htm

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b ICOMOS (14 May 1979). "Advisory Body Evaluation of Timbuktu Nomination" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Mali Government (14 May 1979). "Nomination No. 119" (PDF). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. UNESCO. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Amelan, Roni (13 July 2005). "Three Sites Withdrawn from UNESCO's List of World Heritage in Danger". World Heritage Convention News & Events. UNESCO. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "WHC Requests Close Surveillance of Bordeaux, Machu Picchu, Timbuktu and Samarkand". World Heritage Convention News & Events. UNESCO. 10 July 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Decision 33COM 7B.45 – Timbuktu (Mali)", Final Decisions of the 33rd Session of the WHC, Seville, 2009 http://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/1837

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "Timbuktu shrines damaged by Mali Ansar Dine Islamists". BBC News. 30 June 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012..

- ^ "Mali Islamist militants 'destroy' Timbuktu saint's tomb". BBC News. 6 May 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012..

- ^ Al Jazeera (1 June 2012). Ansar Dine fighters destroy Timbuktu shrines. Retrieved 1 July 2012

- ^ Guled Yusuf and Lucas Bento, The New York Times (31 July 2012). The 'End Times' for Timbuktu? Retrieved 31 July 2012

- ^ http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/913

- ^ a b c Huddleston, Alexandra (1 September 2009). "Divine Learning: The Traditional Islamic Scholarship of Timbuktu". Fourth Genre: Explorations in Non-Fiction. 11 (2). Michigan: Michigan State University Press: 129–135. ISSN 1522-3868.

- ^ a b c Cleaveland 2008.

- ^ Holbrook, Jarita;, Jarita (1 January 2008). The Timbuktu Astronomy Project. Leiden, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6639-9_13.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Makdisi, George (April–June 1989), "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 109 (2), American Oriental Society: 175–182 [176], doi:10.2307/604423, JSTOR 604423

- ^ University of Timbuktu, Mali – Timbuktu Educational Foundation

- ^ Hunwick 2003, pp. lvii.

- ^ Rainier, Chris (27 May 2003). "Reclaiming the Ancient Manuscripts of Timbuktu". National Geographic News. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ Harding, Luke (28 January 2013), Timbuktu mayor: Mali rebels torched library of historic manuscripts, London: The Guardian, retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Diarra, Adama (28 January 2013), French, Malians retake Timbuktu, rebels torch library, Reuters, retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Timbuktu update, Tombouctou Manuscripts Project, University of Cape Town, 30 January 2013, retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Zanganeh, Lila Azam (29 January 2013), Has the great library of Timbuktu been lost?, The New Yorker, retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Precious history in Timbuktu library saved from fire, The History Blog, retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Hinshaw, Drew (1 February 2013), Historic Timbuktu Texts Saved From Burning, The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Grant, Simon (8 February 2007), "Beyond the Saharan Fringe", The Guardian, London, retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ a b Heath 1999, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Forma, Aminatta (7 February 2009). "The Lost Libraries of Timbuktu". The Sunday Times. London, UK. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Rosberg, Carl Gustav (1964), Political Parties and National Integration in Tropical Africa, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, p. 222.

- ^ a b Pitcher, Gemma (2007). Africa. Melbourne: Lonely Planet Guides. pp. 403–418.

- ^ Lancement des travaux du Canal de Tombouctou : la mamelle nourricière redonne vie et espoir à la 'Cité mystérieuse', Afribone, 14 August 2006

- ^ a b Coulibaly, Baye (24 November 2010), Route Tombouctou-Goma Coura: un nouveau chantier titanesque est ouvert, L'Essor, retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Coulibaly, Baye (19 January 2012), Route Tombouctou-Goma Coura: le chantier advance à grand pas, L'Essor, retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Niono-Goma Coura Road Inauguration, Embassy of the United States, Mali, 7 February 2009, retrieved 19 March 2011

- ^ Mali Compact (PDF), Millennium Challenge Corporation, 17 November 2006.

- ^ Pilot Information for Timbuktu Airport, Megginson Technologies, 2010, retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Timbuktu 'twins' make first visit". BBC News. 24 October 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

References

- Abitbol, Michel (1979), Tombouctou et les Arma: de la conquête marocaine du Soudan nigérien en 1591 à l'hégémonie de l'empire Peulh du Macina en 1833 (in French), Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, ISBN 2-7068-0770-9.

- Barth, Heinrich (1857), Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being a journal of an expedition undertaken under the auspices of H. B. M.'s government, in the years 1849–1855. (3 Vols), New York: Harper & Brothers. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3.

- Black, Crofton (2002), "Leo Africanus's "Descrittione dell'Africa" and its sixteenth-century translations", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 65, The Warburg Institute: 262–272, JSTOR 4135111.

- Caillié, Réné (1830), Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo; and across the Great Desert, to Morocco, performed in the years 1824–1828 (2 Vols), London: Colburn & Bentley. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Cleaveland, Timothy (2008), "Timbuktu and Walata: lineages and higher education", in Jeppie, Shamil; Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (eds.), The Meanings of Timbuktu (PDF), Cape Town: HSRC Press, pp. 77–91, ISBN 978-0-7969-2204-5.

- Dubois, Felix (1896), Timbuctoo the mysterious, White, Diana (trans.), New York: Longmans.

- Fage, J.D. (1956), An Introduction to the History of West Africa, London: Cambridge University Press, p. 22

- Hacquard, Augustin (1900), Monographie de Tombouctou, Paris: Société des études coloniales & maritimes. Also available from Gallica.

- Heath, Jeffrey (1999), A Grammar of Koyra Chiini: the Songhay of Timbuktu, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Houdas, Octave (ed. and trans.) (1901), Tedzkiret en-nisiān fi Akhbar molouk es-Soudān (in French), Paris: E. Laroux. The anonymous 18th century Tadhkirat al-Nisyan is a biographical dictionary of the pashas of Timbuktu from the Moroccan conquest up to 1750.

- Hunwick, John O. (2000), "Timbuktu", Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill, pp. 508–510, ISBN 90-04-11211-1.

- Hunwick, John O. (2003), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-12560-4. First published in 1999 as ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Imperato, Pascal James (1989), Mali: A Search for Direction, Boulder CO: Westview Press, ISBN 1-85521-049-5.

- Insoll, Timothy (2002), "The Archaeology of Post Medieval Timbuktu" (PDF), Sahara, 13: 7–22.

- Insoll, Timothy (2004), "Timbuktu the less Mysterious?" (PDF), in Mitchell, P.; Haour, A.; Hobart, J. (eds.), Researching Africa's Past. New Contributions from British Archaeologists, Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 81–88.

- Jackson, James Grey (1820), An Account of Timbuctoo and Housa, Territories in the Interior of Africa By El Hage Abd Salam Shabeeny, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- Jeppie, Shamil (2008), "Re/discovering Timbuktu", in Jeppie, Shamil; Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (eds.), The Meanings of Timbuktu (PDF), Cape Town: HSRC Press, pp. 1–17, ISBN 978-0-7969-2204-5.

- Kaba, Lansine (1981), "Archers, Musketeers, and Mosquitoes: The Moroccan Invasion of the Sudan and the Songhay Resistance (1591–1612)", Journal of African History, 22 (4): 457–475, doi:10.1017/S0021853700019861, JSTOR 181298, PMID 11632225.

- Kâti, Mahmoûd Kâti ben el-Hâdj el-Motaouakkel (1913), Tarikh el-fettach ou Chronique du chercheur, pour servir à l'histoire des villes, des armées et des principaux personnages du Tekrour (in French), Houdas, O., Delafosse, M. ed. and trans., Paris: Ernest Leroux. Also available from Aluka but requires subscription.

- Leo Africanus (1896), The History and Description of Africa (3 Vols), Brown, Robert, editor, London: Hakluyt Society. A facsimile of Pory's English translation of 1600 together with an introduction and notes by the editor. Internet Archive: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN 0-8419-0431-6. Link requires subscription to Aluka.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York, NY: Marcus Weiner Press, ISBN 1-55876-241-8. First published in 1981 by Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22422-5.

- McIntosh, Susan Keech; McIntosh, Roderick J. (1986), "Archaeological reconnaissance in the region of Timbuktu", National Geographic Research, 2: 302–319.

- Miner, Horace (1953), The primitive city of Timbuctoo, Princeton University Press. Link requires subscription to Aluka. Reissued by Anchor Books, New York in 1965.

- Park, Douglas (2010), "Timbuktu and its prehistoric hinterland", Antiquity, 84: 1076–1088.

- Park, Douglas (2011), Climate Change, Human Response and the Origins of Urbanism at Prehistoric Timbuktu, New Haven: PhD thesis, Yale University, Department of Anthropology.

- Saad, Elias N. (1983), Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24603-2.

Further reading

- es-Sadi, Abderrahman (1898–1900), Tarikh es-Soudan, Houdas, Octave ed. and trans., Paris: E. Leroux. (Vol. 1 contains the Arabic text, Vol. 2 contains a translation into French). Internet Archive: Volume 1; Volume 2; Gallica: Volume 2.

- Cisse, Mamadou (2011), Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney (Mali), PhD Thesis, Rice University, Department of Anthropology.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005), The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24385-4. Originally published in 1986, ISBN 0-520-05771-6.

- Gramont, Sanche de (1976), The Strong Brown God: The story of the Niger River, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-25224-5.

- Hunwick, John O.; Boye, Alida Jay; Hunwick, Joseph (2008), The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Historic city of Islamic Africa, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-51421-4.

- Joffre, Joseph (1895), Opérations de la colonne Joffre avant et après l'occupation de Tombouctou (in French), Paris: Berger-Levrault.

- Joffre, Joseph; Dimnet, Ernest (ed. and trans.) (1915), My March to Timbuctoo, New York City: Druffield.

- Kryza, Frank T. (2006), The race for Timbuktu: In search of Africa's city of gold, New York City: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-06-056064-9.

- Masonen, Pekka (2000), The Negroland Revisited: Discovery and Invention of the Sudanese Middle Ages, Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, ISBN 951-41-0886-8.

- Mauny, Raymond (1961), Tableau géographique de l'ouest africain au moyen age, d'après les sources écrites, la tradition et l'archéologie (in French), Dakar: Institut français d'Afrique Noire.

- McIntosh, Roderick J. (2008), "Before Timbuktu: Cities of the elder world", in Jeppie, Shamil; Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (eds.), The Meanings of Timbuktu (PDF), Cape Town: HSRC Press, pp. 31–43, ISBN 978-0-7969-2204-5.

- Morse, Jedidiah; Richard C. Morse (1823), "Tombuctou", A New Universal Gazetteer (4th ed.), New Haven: S. Converse

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Park, Douglas; Coutros, Peter; Abdallahi, Mohamoud; Ould Sidi, Ali (2010), Rapport sur la troisiéme champagne de research à Tombouctou préhistorique (in French), Field Report to the Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel, Bamako

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Park, Douglas; Coutros, Useman; Kone (2009), Rapport sur la deuxiéme champagne de research à Tombouctou préhistorique (in French), Field Report to the Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel, Bamako

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Park, Douglas; Togola, Boubacar (2008), Rapport sur la première champagne de research à Tombouctou préhistorique (in French), Field Report to the Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel, Bamako

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Staros, Kari A. (1996), Route to Glory: The Developments of the Trans-Saharan and Trans-Mediterranean Trade Routes, SI University Honor Theses.

- Trimingham, John Spencer (1962), A History of Islam in West Africa, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-285038-5.

External links

select an article title from: Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Jeppie, Ahamil "A Timbuktu book collector between the Mediterranean and Sahel", Video of a presentation given at the conference The southern shores of the Mediterranean and beyond: 1800 – to the present held at the University of Minnesota in April 2013.

- Saharan Archaeological Research Association – contains information on the archaeological projects targeting the Iron Age occupation of Timbuktu

- Ancient West Africa's Megacities – contains video footage of Timbuktu's Iron Age occupation

- Islamic Manuscripts from Mali, Library of Congress – fuller presentation of the same manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library

- Timbuktu materials in the Aluka digital library

- Timbuktu manuscripts: Africa's written history unveiled, The UNESCO Courier, 2007-5, pp. 7–9