Toxoplasma gondii

| Toxoplasma gondii | |

|---|---|

| |

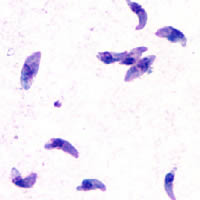

| T. gondii tachyzoites | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Superphylum: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Toxoplasma

|

| Species: | T. gondii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle & Manceaux, 1908)

| |

Toxoplasma gondii (tŏk'sə-plāz'mə gŏn'dē-ī') is an obligate, intracellular, parasitic protozoan that causes the disease toxoplasmosis.[1]

Found worldwide, T. gondii is capable of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals.[2] In humans, it is one of the most common parasites;[3] serological studies estimate that up to a third of the global population has been exposed to and may be chronically infected with T. gondii, although infection rates differ significantly from country to country.[4] Although mild, flu-like symptoms occasionally occur during the first few weeks following exposure, infection with T. gondii generally produces no symptoms in healthy human adults.[5][6] However, in infants, HIV/AIDS patients, and others with weakened immunity, infection can cause serious and occasionally fatal illness (toxoplasmosis).[5][6]

Infection in humans and other warm-blooded animals can occur

- by consuming raw or undercooked meat containing T. gondii tissue cysts[7]

- by ingesting water, soil, vegetables, or anything contaminated with oocysts shed in the feces of an infected animal[7]

- from a blood transfusion or organ transplant

- or transplacental transmission from mother to fetus, particularly when T. gondii is contracted during pregnancy[7]

Although T. gondii can infect, be transmitted by, and asexually reproduce within humans and virtually all other warm-blooded animals, the parasite can sexually reproduce only within the intestines of members of the cat family (felids).[8] Felids are therefore defined as the definitive hosts of T. gondii, with all other hosts defined as intermediate hosts.

T. gondii has been shown to alter the behavior of infected rodents in ways thought to increase the rodents' chances of being preyed upon by cats.[9][10][11] Because cats are the only hosts within which T. gondii can sexually reproduce to complete and begin its lifecycle, such behavioral manipulations are thought to be evolutionary adaptations to increase the parasite's reproductive success,[11] in one of the manifestations the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins attributes to the "extended phenotype". Although numerous hypotheses exist and are being investigated, the mechanism of T. gondii–induced behavioral changes in rodents remains unknown.[12]

A number of studies have suggested subtle behavioral or personality changes may occur in infected humans,[13] and infection with the parasite has recently been associated with a number of neurological disorders, particularly schizophrenia.[10] However, evidence for causal relationships remains limited.[10]

Lifecycle

The lifecycle of T. gondii can be broadly summarized into two components: 1) a sexual component that occurs only within cats (felids, wild or domestic), and 2) an asexual component that can occur within virtually all warm-blooded animals, including humans, cats, and birds.[14] Because T. gondii can sexually reproduce only within cats, they are defined as the definitive host of T. gondii. All other hosts – hosts in which only asexual reproduction can occur – are defined as intermediate hosts.

Sexual reproduction in the feline definitive host

When a member of the cat family is infected with T. gondii (e.g. by consuming an infected mouse laden with the parasite's tissue cysts), the parasite survives passage through the stomach, eventually infecting epithelial cells of the cat's small intestine.[15] Inside these intestinal cells, the parasites undergo sexual development and reproduction, producing millions of thick-walled, zygote-containing cysts known as oocysts.

Feline shedding of oocysts

Infected epithelial cells eventually rupture and release oocysts into the intestinal lumen, whereupon they are shed in the cat's feces.[16] Oocysts can then spread to soil, water, food, or anything potentially contaminated with the feces. Highly resilient, oocysts can survive and remain infective for many months in cold and dry climates.[17]

Ingestion of oocysts by humans or other warm-blooded animals is one of the common routes of infection.[8] Humans can be exposed to oocysts by, for example, consuming unwashed vegetables or contaminated water, or by handling the feces (litter) of an infected cat.[14][18] Although cats can also be infected by ingesting oocysts, they are much less sensitive to oocyst infection than are intermediate hosts.[19][20]

Initial infection of the intermediate host

When an oocyst or tissue cyst is ingested by a human or other warm-blooded animal, the resilient cyst wall is dissolved by proteolytic enzymes in the stomach and small intestine, freeing infectious T. gondii parasites to invade host cells.[8] The parasites first invade cells in and surrounding the intestinal epithelium, and inside these cells, the parasites convert to tachyzoites, the motile and quickly multiplying cellular stage of T. gondii.[15]

Asexual reproduction in the intermediate host

Inside host cells, the tachyzoites replicate inside specialized vacuoles (called the parasitophorous vacuoles) created during parasitic entry into the cell.[21] Tachyzoites multiply inside this vacuole until the host cell dies and ruptures, releasing and spreading the tachyzoites via the blood stream to all organs and tissues of the body, including the brain.[22]

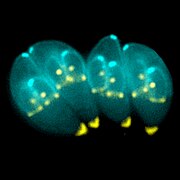

Formation of tissue cysts

Following the initial period of infection characterized by tachyzoite proliferation throughout the body, pressure from the host's immune system causes T. gondii tachyzoites to convert into bradyzoites, the semidormant, slowly dividing cellular stage of the parasite.[23] Inside host cells, clusters of these bradyzoites are known as tissue cysts. The cyst wall is formed by the parasitophorous vacuole membrane.[24] Although bradyzoite-containing tissue cysts can form in virtually any organ, tissue cysts predominantly form and persist in the brain, the eyes, and striated muscle (including the heart).[24] However, specific tissue tropisms can vary between species; in pigs, the majority of tissue cysts are found in muscle tissue, whereas in mice, the majority of cysts are found in the brain.[25]

Cysts usually range in size between five and 50 µm in diameter,[26] (with 50 µm being about two-thirds the width of the average human hair).[27]

Consumption of tissue cysts in meat is one of the primary means of T. gondii infection, both for humans and for meat-eating, warm-blooded animals.[28] Humans consume tissue cysts when eating raw or undercooked meat (particularly pork and lamb).[29] Tissue cyst consumption is also the primary means by which cats are infected.[30]

Chronic infection

Tissue cysts can be maintained in host tissue for the lifetime of the animal.[31] However, the perpetual presence of cysts appears to be due to a periodic process of cyst rupturing and re-encysting, rather than a perpetual lifespan of individual cysts or bradyzoites.[31] At any given time in a chronically infected host, a very small percentage of cysts are rupturing,[32] although the exact cause of this tissue cysts rupture is, as of 2010, not yet known.[33]

T. gondii can, theoretically, be passed between intermediate hosts indefinitely via a cycle of consumption of tissue cysts in meat. However, the parasite's lifecycle begins and completes only when the parasite is passed to a feline host, the only host within which the parasite can again undergo sexual development and reproduction.[8]

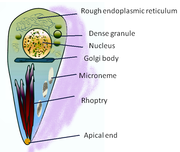

Cellular stages

During different periods of its lifecycle, individual parasites convert into various cellular stages, with each stage characterized by a distinct cellular morphology, biochemistry, and behavior. These stages include the tachyzoites, merozoites, bradyzoites (found in tissue cysts), and sporozoites (found in oocysts).

Tachyzoites

Motile, and quickly multiplying, tachyzoites are responsible for expanding the population of the parasite in the host.[34] When a host consumes a tissue cyst (containing bradyzoites) or an oocyst (containing sporozoites), the bradyzoites or sporozoites stage-convert into tachyzoites upon infecting the intestinal epithelium of the host.[35] During the initial, acute period of infection, tachyzoites spread throughout the body via the blood stream.[22] During the later, latent (chronic) stages of infection, tachyzoites stage-convert to bradyzoites to form tissue cysts.

Merozoites

Like tachyzoites, merozoites divide quickly, and are responsible for expanding the population of the parasite inside the cat intestine prior to sexual reproduction.[34] When a feline definitive host consumes a tissue cyst (containing bradyzoites), bradyzoites convert into merozoites inside intestinal epithelial cells. Following a brief period of rapid population growth in the intestinal epithelium, merozoites convert into the noninfectious sexual stages of the parasite to undergo sexual reproduction, eventually resulting in the formation of zygote-containing oocysts.[36]

Bradyzoites

Bradyzoites are the slowly dividing stage of the parasite that make up tissue cysts. When an uninfected host consumes a tissue cyst, bradyzoites released from the cyst infect intestinal epithelial cells before converting to the proliferative tachyzoite stage.[35] Following the initial period of proliferation throughout the host body, tachyzoites then convert back to bradyzoites, which reproduce inside host cells to form tissue cysts in the new host.

Sporozoites

Sporozoites are the stage of the parasite residing within oocysts. When a human or other warm-blooded host consumes an oocyst, sporozoites are released from it, infecting epithelilal cells before converting to the proliferative tachyzoite stage.[35]

Risk factors for human infection

The following have been identified as being risk factors for T. gondii infection:

- Exposure to or consumption of raw or undercooked meat[18][37][38][39]

- Drinking unpasteurized goat milk[37]

- Contact with soil[7][38]

- Eating unwashed raw vegetables or fruits[18]

- Cleaning cat litter boxes[18]

Sewage has been identified as a carriage medium for the organism.[40][41][42][43]

Numerous studies have shown living in a household with a cat is not a significant risk factor for T. gondii infection,[18][38][44] though living with several kittens has some significance.[45]

Preventing infection

This article contains instructions, advice, or how-to content. (April 2013) |

The following precautions are recommended to prevent or greatly reduce the chances of becoming infected with T. gondii. This information has been adapted from the websites of United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[46] and the Mayo Clinic.[47]

From food

- Peel or wash all fruits and vegetables thoroughly before eating.

- Freeze meat for several days at subzero temperatures (0°F or −18°C) before cooking. Tissue cysts rarely survive freezing at these temperatures.[48]

- Avoid eating raw or undercooked meat, and never taste meat before fully cooked:

- Cook whole cuts of red meat to an internal temperature of 145°F (63°C). "Medium rare" meat is generally cooked between 130 and 140°F (55 and 60°C),[49] so cooking whole cuts of meat to "medium" is recommended. After cooking, a rest period of 3 min should be allowed before consumption.

- Cook ground meat to an internal temperature of at least 160°F (71°C). No rest time is needed for properly cooked ground meats.

- Cook all poultry (whole or ground) to an internal temperature of at least 165°F (74°C). After cooking, a rest period of 3 min should be allowed before consumption.

- Use hot, soapy water to wash hands or anything in the kitchen that contacts raw meat, poultry, seafood or unwashed fruits and vegetables.

- Avoid drinking unpasteurized milk.

From environment

- Change and dispose of cat litter daily. Oocysts in cat feces take at least a day to sporulate and become infectious after they are shed, so disposing of cat litter greatly reduces the chances of infectious oocysts being present in litter. Wash hands after changing cat litter.

- Wear gloves when gardening or when in contact with soil or sand, as infectious oocysts from cat feces can spread and survive in the environment for months.

- Avoid drinking untreated water.

- Cover outdoor sandboxes when not being used.

If pregnant or immunocompromised

- Do not change or handle cat litter boxes. If absolutely necessary, wear gloves and wash hands with hot, soapy water immediately afterwards.

- Keep cats indoors, and only feed them commercial canned or dry food, or well-cooked table food.

- Do not adopt or handle stray cats, particularly kittens.

- Do not get a new cat while pregnant.

History

In 1908, while working at the Pasteur Institute in Tunis, Charles Nicolle and Louis Manceaux discovered a protozoan organism in the tissues of a hamster-like rodent known as the gundi, Ctenodactylus gundi.[8] Although Nicolle and Mancaeux initially believed the organism to be the parasite Leishmania, they soon realized they had discovered a new organism entirely. They named it Toxoplasma gondii, a reference to its morphology (Toxo, from Greek τόξον (toxon); arc, bow, and πλάσμα (plasma); i.e., anything shaped or molded) and the host in which it was discovered, the gundi (gondii). The same year Nicolle and Mancaeux discovered T. gondii, Alfonso Splendore identified the same organism in a rabbit in Brazil. However, he did not give it a name.[8]

The first conclusive identification of T. gondii in humans was in an infant girl delivered full term by Caesarean section on May 23, 1938, at Babies' Hospital in New York City.[8] The girl began having seizures at three days of age, and doctors identified lesions in the maculae of both of her eyes. When she died at one month of age, an autopsy was performed. Lesions discovered in her brain and eye tissue were found to have both free and intracellular T. gondii'.[8] Infected tissue from the girl was homogenized and inoculated intracerebrally into rabbits and mice; the animals subsequently developed encephalitis. Later, congenital transmission was found to occur in numerous other species, particularly in sheep and rodents.

The possibility of T. gondii transmission via consumption of undercooked meat was first proposed by D. Weinman and A.H Chandler in 1954.[8] In 1960, the cyst wall of tissue cysts was shown to dissolve in the proteolytic enzymes found in the stomach, releasing infectious bradyzoites into the stomach (and subsequently into the intestine). The hypothesis of transmission via consumption of undercooked meat was tested in an orphanage in Paris in 1965; yearly acquisition rates of T. gondii rose from 10% to 50% after adding two portions of barely cooked beef or horse meat to the orphans' daily diets, and to 100% after adding barely cooked lamb chops.[8]

In 1959, a study in Bombay found the prevalence of T. gondii in strict vegetarians to be similar to that found in nonvegetarians. This raised the possibility of a third major route of infection, beyond congenital and carnivorous transmission.[8] In 1970, the existence of oocysts was discovered in cat feces, and the fecal-oral route of infection via oocysts was demonstrated.[8]

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, a vast number of species were tested for the ability to shed oocysts upon infection. Whereas at least 17 different species of felids have been confirmed to shed oocysts, no nonfelid has been shown to be permissive for T. gondii sexual reproduction and subsequent oocyst shedding.[8]

References

- ^ Weiss, Louis M. & Kami Kim, eds. (2011) Toxoplasma Gondii: The Model Apicomplexan. Perspectives and Methods. Academic Press/Elsevier, London. p. 49

- ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 1

- ^ "CDC – About Parasites". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Pappas, G (October 2009). "Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis". International Journal for Parasitology. 39 (12): 1385–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.04.003. PMID 19433092.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "CDC Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) – Disease". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ a b J.P Dubey (2010) p. 77

- ^ a b c d Tenter, AM (November 2000). "Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans". International Journal for Parasitology. 30 (12–13): 1217–58. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7. PMC 3109627. PMID 11113252.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Dubey, JP (Jul 1, 2009). "History of the discovery of the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii". International Journal for Parasitology. 39 (8): 877–82. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.01.005. PMID 19630138.

- ^ Webster, JP (May 2007). "The effect of Toxoplasma gondii on animal behavior: playing cat and mouse". Schizophrenia bulletin. 33 (3): 752–6. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl073. PMC 2526137. PMID 17218613.

- ^ a b c Webster, JP (Jan 1, 2013). "Toxoplasma gondii infection, from predation to schizophrenia: can animal behaviour help us understand human behaviour?". The Journal of experimental biology. 216 (Pt 1): 99–112. doi:10.1242/jeb.074716. PMC 3515034. PMID 23225872.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Berdoy, M (Aug 7, 2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proceedings. Biological sciences / the Royal Society. 267 (1452): 1591–4. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182. PMC 1690701. PMID 11007336.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McConkey, GA (Jan 1, 2013). "Toxoplasma gondii infection and behaviour – location, location, location?". The Journal of experimental biology. 216 (Pt 1): 113–9. doi:10.1242/jeb.074153. PMC 3515035. PMID 23225873.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Flegr, J (Jan 1, 2013). "Influence of latent Toxoplasma infection on human personality, physiology and morphology: pros and cons of the Toxoplasma-human model in studying the manipulation hypothesis". The Journal of experimental biology. 216 (Pt 1): 127–33. doi:10.1242/jeb.073635. PMID 23225875.

- ^ a b Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 2

- ^ a b Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 39

- ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 22

- ^ Dubey, JP (October 2011). "Sporulation and survival of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in different types of commercial cat litter". The Journal of parasitology. 97 (5): 751–4. doi:10.1645/GE-2774.1. PMID 21539466.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Kapperud, G (Aug 15, 1996). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnancy. Results of a prospective case-control study in Norway". American Journal of Epidemiology. 144 (4): 405–12. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008942. PMID 8712198.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dubey, JP (July 1998). "Advances in the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii". International Journal for Parasitology. 28 (7): 1019–24. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00023-X. PMID 9724872.

- ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 107

- ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) pp. 23–29

- ^ a b Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) pp. 39–40

- ^ Miller, CM (January 2009). "The immunobiology of the innate response to Toxoplasma gondii". International Journal for Parasitology. 39 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.08.002. PMID 18775432.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 343

- ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 41

- ^ "CDC Toxoplasmosis – Microscopy Findings". Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Clarence R. Robbins (24 February 2012). Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair. Springer. p. 585. ISBN 978-3-642-25610-3. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 3

- ^ Jones, JL (September 2012). "Foodborne toxoplasmosis". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 55 (6): 845–51. doi:10.1093/cid/cis508. PMID 22618566.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 46

- ^ a b Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 580

- ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 45

- ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 47

- ^ a b Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 19

- ^ a b c Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 359

- ^ Louis M Weiss, Kami Kim (2011) p. 306

- ^ a b Jones, JL (Sep 15, 2009). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 49 (6): 878–84. doi:10.1086/605433. PMID 19663709.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Cook, AJ (Jul 15, 2000). "Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 321 (7254): 142–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7254.142. PMC 27431. PMID 10894691.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sakikawa, M (March 2012). "Anti-Toxoplasma antibody prevalence, primary infection rate, and risk factors in a study of toxoplasmosis in 4,466 pregnant women in Japan". Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 19 (3): 365–7. doi:10.1128/CVI.05486-11. PMC 3294603. PMID 22205659.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.10.007, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.10.007instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1645/GE-2453.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1645/GE-2453.1instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.036, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.036instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1645/GE-2836.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1645/GE-2836.1instead. - ^ Bobić, B (September 1998). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in a reproductive age female population in the area of Belgrade, Yugoslavia". European journal of epidemiology. 14 (6): 605–10. doi:10.1023/A:1007461225944. PMID 9794128.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/605433, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/605433instead. - ^ "CDC: Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) – Prevention & Control". Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Mayo Clinic – Toxoplasmosis – Prevention". Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ J.P Dubey (2010) p. 45

- ^ Green, Aliza (2005). Field Guide to Meat. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books. pp. 294–295. ISBN 1-59474-017-8.

Bibliography

- Louis M Weiss; Kami Kim (28 April 2011). Toxoplasma Gondii: The Model Apicomplexan. Perspectives and Methods. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-047501-1. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- J. P. Dubey (15 April 2010). Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-9237-0. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

External links

- ToxoDB : The Toxoplasma gondii genome resource

- Anti-Toxo : A Toxoplasma news blog and list of research laboratories

- Toxoplasma images, from CDC's DPDx, in the public domain

- Toxoplasmosis Research Institute & Center

- Cytoskeletal Components of an Invasion Machine – The Apical Complex of Toxoplasma gondii

- The Culture-Shaping Parasites, in Seed Magazine

- Sneaky Parasite Attracts Rats to Cats, All Things Considered, April 14, 2007

- Toxoplasma overview, developmental stages, life cycle image at MetaPathogen

- Toxoplasma lecture, Robert Sapolsky

- Could a brain parasite found in cats help soccer teams win at the World Cup?, – By Patrick House – Slate Magazine

- How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy, the Atlantic Magazine, March 2012

- Mystery Marine Mammal Deaths, CosmosMagazine.com, June 2008

- Toxoplasma gondii in the Subarctic and Arctic

- The T.Gondii host/pathogen interactome

- Toxoplasmosis – Recent advances, Open access book published in September 2012

- Toxoplasma gondii, the Immune System, and Suicidal Behaviour