Will and testament

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Wills, trusts and estates |

|---|

|

| Part of the common law series |

| Wills |

|

Sections Property disposition |

| Trusts |

|

Common types Other types

Governing doctrines |

| Estate administration |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

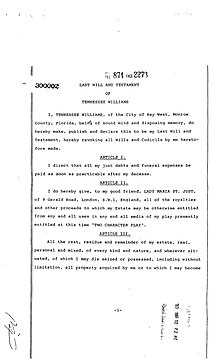

A will or testament is a legal document by which a person, the testator, expresses his or her wishes as to how his or her property is to be distributed at death, and names one or more persons, the executor, to manage the estate until its final distribution. For the devolution of property not disposed of by will, see inheritance and intestacy.

Though it has at times been thought that a "will" was historically limited to real property while "testament" applies only to dispositions of personal property (thus giving rise to the popular title of the document as "Last Will and Testament"), the historical records show that the terms have been used interchangeably.[1] Thus, the word "will" validly applies to both personal and real property. A will may also create a testamentary trust that is effective only after the death of the testator.

History

Throughout most of the world, disposal of an estate has been a matter of social custom. According to Plutarch, the written will was invented by Solon. Originally it was a device intended solely for men who died without an heir.

The English phrase "will and testament" is derived from a period in English law when Old English and Law French were used side by side for maximum clarity. Other such legal doublets include "breaking and entering" and "peace and quiet".[2]

Freedom of disposition

The conception of the freedom of disposition by will, familiar as it is in modern England and the United States, both generally considered common law systems, is by no means universal. In fact, complete freedom is the exception rather than the rule. Civil law systems often put some restrictions on the possibilities of disposal; see for example "Forced heirship".

Advocates for gays and lesbians have pointed to the inheritance rights of spouses as desirable for same-sex couples as well, through same-sex marriage or civil unions. Opponents of such advocacy rebut this claim by pointing to the ability of same-sex couples to disperse their assets by will. Historically, however, it was observed that "[e]ven if a same-sex partner executes a will, there is risk that the survivor will face prejudice in court when disgruntled heirs challenge the will",[3] with courts being more willing to strike down wills leaving property to a same-sex partner on such grounds as incapacity or undue influence.[4][5]

Types of wills

Types of wills generally include:

- nuncupative (non-culpatory) - oral or dictated; often limited to sailors or military personnel.

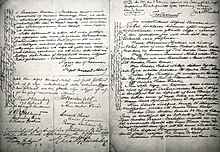

- holographic will - written in the hand of the testator; in many jurisdictions, the signature and the material terms of the holographic will must be in the handwriting of the testator.

- self-proved - in solemn form with affidavits of subscribing witnesses to avoid probate.

- notarial - will in public form and prepared by a civil-law notary (civil-law jurisdictions and Louisiana, United States).

- mystic - sealed until death.

- serviceman's will - will of person in active-duty military service and usually lacking certain formalities, particularly under English law.

- reciprocal/mirror/mutual/husband and wife wills - wills made by two or more parties (typically spouses) that make similar or identical provisions in favor of each other.

- unsolemn will - will in which the executor is unnamed.

- will in solemn form - signed by testator and witnesses.

Some jurisdictions recognize a holographic will, made out entirely in the testator's own hand, or in some modern formulations, with material provisions in the testator's hand. The distinctive feature of a holographic will is less that it is handwritten by the testator and often that it need not be witnessed. In Louisiana this type of testament is called an Olographic or Mystic will.[6] It must be entirely written, dated, and signed in the handwriting of the testator. Although the date may appear anywhere in the testament, the testator must sign the testament at the end of the testament. Any additions or corrections must also be entirely hand written to have effect. In England, the formalities of wills are relaxed for soldiers who express their wishes on active service; any such will is known as a serviceman's will. A minority of jurisdictions even recognize the validity of nuncupative wills (oral wills), particularly for military personnel or merchant sailors. However, there are often constraints on the disposition of property if such an oral will is used.

Terminology

- Administrator - person appointed or who petitions to administer an estate in an intestate succession. The antiquated English term of administratrix was used to refer to a female but is generally no longer in standard legal usage.

- Beneficiary - anyone receiving a gift or benefitting from a trust

- Bequest - testamentary gift of personal property, traditionally other than money.

- Codicil - (1) amendment to a will; (2) a will that modifies or partially revokes an existing or earlier will.

- Decedent - the deceased (U.S. term)

- Demonstrative Legacy - a gift of a specific sum of money with a direction that is to be paid out of a particular fund.

- Descent - succession to real property.

- Devise - testamentary gift of real property.

- Devisee - beneficiary of real property under a will.

- Distribution - succession to personal property.

- Executor/executrix or personal representative [PR] - person named to administer the estate, generally subject to the supervision of the probate court, in accordance with the testator's wishes in the will. In most cases, the testator will nominate an executor/PR in the will unless that person is unable or unwilling to serve. In some cases a literary executor may be appointed to manage a literary estate.

- Exordium clause is the first paragraph or sentence in a will and testament, in which the testator identifies himself or herself, states a legal domicile, and revokes any prior wills.

- Inheritor - a beneficiary in a succession, testate or intestate.

- Intestate - person who has not created a will, or who does not have a valid will at the time of death.

- Legacy - testamentary gift of personal property, traditionally of money. Note: historically, a legacy has referred to either a gift of real property or personal property.

- Legatee - beneficiary of personal property under a will, i.e., a person receiving a legacy.

- Probate - legal process of settling the estate of a deceased person.

- Specific legacy (or specific bequest) - a testamentary gift of a precisely identifiable object.

- Testate - person who dies having created a will before death.

- Testator - person who executes or signs a will; that is, the person whose will it is. The antiquated English term of Testatrix was used to refer to a female and is still in use in the US.[citation needed]

Requirements for creation

Any person over the age of majority and having "testamentary capacity" (ie., generally, being of sound mind) can make a will, with or without the aid of a lawyer. Additional requirements may vary, depending on the jurisdiction, but generally include the following requirements:

- The testator must clearly identify himself as the maker of the will, and that a will is being made; this is commonly called "publication" of the will, and is typically satisfied by the words "last will and testament" on the face of the document.

- The testator should declare that he revokes all previous wills and codicils. Otherwise, a subsequent will revokes earlier wills and codicils only to the extent to which they are inconsistent. However, if a subsequent will is completely inconsistent with an earlier one, the earlier will is considered completely revoked by implication.

- The testator may demonstrate that he has the capacity to dispose of his or her property ("sound mind"), and does so freely and willingly.

- The testator must sign and date the will, usually in the presence of at least two disinterested witnesses (persons who are not beneficiaries). There may be extra witnesses, these are called "supernumerary" witnesses, if there is a question as to an interested-party conflict. Some jurisdictions, notably Pennsylvania, have long abolished any requirement for witnesses. In the United States, Louisiana requires both attestation by two witnesses as well as notarization by a notary public. "Holographic" or handwritten wills generally require no witnesses to be valid.

- If witnesses are designated to receive property under the will they are witnesses to, this has the effect, in many jurisdictions, of either (i) disallowing them to receive under the will, or (ii) invalidating their status as a witness. In a growing number of states in the United States, however, an interested party is only an improper witness as to the clauses that benefit him or her (for instance, in Illinois).

- The testator's signature must be placed at the end of the will. If this is not observed, any text following the signature will be ignored, or the entire will may be invalidated if what comes after the signature is so material that ignoring it would defeat the testator's intentions.

- One or more beneficiaries (devisees, legatees) must generally be clearly stated in the text, but some jurisdictions allow a valid will that merely revokes a previous will, revokes a disposition in a previous will, or names an executor.

There is no legal requirement that a will be drawn up by a lawyer, although there are pitfalls into which home-made wills can fall. The person who makes a will is not available to explain him or herself, or to correct any technical deficiency or error in expression, when it comes into effect on that person's death, and so there is little room for mistake. A common error, for example, in the execution of home-made wills in England is to use a beneficiary (typically a spouse or other close family members) as a witness – which may have the effect in law of disinheriting the witness regardless of the provisions of the will.

A will may not include a requirement that an heir commit an illegal, immoral, or other act against public policy as a condition of receipt. In community property jurisdictions, a will cannot be used to disinherit a surviving spouse, who is entitled to at least a portion of the testator's estate. In the United States, children may be disinherited by a parent's will, except in Louisiana, where a minimum share is guaranteed to surviving children. Many civil law countries follow a similar rule. In England and Wales from 1933 to 1975, a will could disinherit a spouse but since the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 such an attempt can be defeated by a court order if it leaves the surviving spouse (or other entitled dependent) without reasonable financial provision.

International wills

In 1973 an international convention, the Convention providing a Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will,[7] was concluded in the context of UNIDROIT. The Convention provided for a universally recognised code of rules under which a will made anywhere, by any person of any nationality, would be valid and enforceable in every country which became a party to the Convention. These are known as "international wills". Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Canada (for 9 provinces, not Quebec), Cyprus, Ecuador, France, Italy, Libya, Niger, Portugal and Slovenia. The Holy See, Iran, Laos, the Russian Federation, Sierra Leone, the United Kingdom, and the United States have signed but not ratified.[8] International wills are only valid where the convention applies. Although the US has not ratified on behalf of any state, the Uniform law has been enacted in 23 States and the District of Columbia).[citation needed]

For individuals who own assets in multiple countries and at least one of those countries are not a part of the Convention, it is advised to have multiple wills, one for each country.[8][9]

Revocation

Methods and effect

Intentional physical destruction of a will by the testator will revoke it, through deliberately burning or tearing the physical document itself, or by striking out the signature. In most jurisdictions, partial revocation is allowed if only part of the text or a particular provision is crossed out. Other jurisdictions will either ignore the attempt or hold that the entire will was actually revoked. A testator may also be able to revoke by the physical act of another (as would be necessary if he or she is physically incapacitated), if this is done in his or her presence and in the presence of witnesses. Some jurisdictions may presume that a will has been destroyed if it had been last seen in the possession of the testator but is found mutilated or cannot be found after his or her death.

A will may also be revoked by the execution of a new will. Most wills contain stock language that expressly revokes any wills that came before them, however, because normally a court will still attempt to read the wills together to the extent they are consistent.

In some jurisdictions, the complete revocation of a will automatically revives the next most recent will, while others hold that revocation leaves the testator with no will so that his or her heirs will instead inherit by intestate succession.

In England and Wales, marriage will automatically revoke a will as it is presumed that upon marriage, a testator will want to review the will. A statement in a will that it is made in contemplation of forthcoming marriage to a named person will override this.

Divorce, conversely, will not revoke a will, but in many jurisdictions, will have the effect that the former spouse is treated as if they had died before the testator and so will not benefit.

Where a will has been accidentally destroyed, on evidence that this is the case, a copy will or draft will may be admitted to probate.

Dependent relative revocation

Many jurisdictions exercise an equitable doctrine known as dependent relative revocation ("DRR"). Under this doctrine, courts may disregard a revocation that was based on a mistake of law on the part of the testator as to the effect of the revocation. For example, if a testator mistakenly believes that an earlier will can be revived by the revocation of a later will, the court will ignore the later revocation if the later will comes closer to fulfilling the testator's intent than not having a will at all. The doctrine also applies when a testator executes a second, or new will and revokes his or her old will under the (mistaken) belief that the new will would be valid. However, if for some reason the new will is not valid, a court may apply the doctrine to reinstate and probate the old will, if the court holds that the testator would prefer the old will to intestate succession.

Before applying the doctrine, courts may require (with rare exceptions) that there have been an alternative plan of disposition of the property. That is, after revoking the prior will, the testator could have made an alternative plan of disposition. Such a plan would show that the testator intended the revocation to result in the property going elsewhere, rather than just being a revoked disposition. Secondly, courts require either that the testator have recited his or her mistake in the terms of the revoking instrument, or that the mistake be established by clear and convincing evidence. For example, when the testator made the original revocation, he must have erroneously noted that he was revoking the gift "because the intended recipient has died" or "because I will enact a new will tomorrow."

DRR may be applied to restore a gift erroneously struck from a will if the intent of the testator was to enlarge that gift, but will not apply to restore such a gift if the intent of the testator was to revoke the gift in favor of another person. For example, suppose Tom has a will that bequeaths $5,000 to his secretary, Alice Johnson. If Tom crosses out that clause and writes "$7,000 to Alice Johnson" in the margin, but does not sign or date the writing in the margin, most states would find that Tom had revoked the earlier provision, but had not effectively amended his will to add the second; however, under DRR the revocation would be undone because Tom was acting under the mistaken belief that he could increase the gift to $7,000 by writing that in the margin. Therefore, Alice will get 5,000 dollars. However, the doctrine of relative revocation will not apply if the interlineation decreases the amount of the gift from the original provision (e.g., "$5,000 to Alice Johnson" is crossed out and replaced with "$3,000 to Alice Johnson" without Testator's signature or the date in the margin; DRR does not apply and Alice Johnson will take nothing).

Similarly, if Tom crosses out that clause and writes in the margin "$5,000 to Betty Smith" without signing or dating the writing, the gift to Alice will be effectively revoked. In this case, it will not be restored under the doctrine of DRR because even though Tom was mistaken about the effectiveness of the gift to Betty, that mistake does not affect Tom's intent to revoke the gift to Alice. Because the gift to Betty will be invalid for lack of proper execution, that $5,000 will go to Tom's residuary estate.

Election against the will

Also referred to as "electing to take against the will." In the United States, many states have probate statutes which permit the surviving spouse of the decedent to choose to receive a particular share of deceased spouse's estate in lieu of receiving the specified share left to him or her under the deceased spouse's will. As a simple example, under Iowa law (see Code of Iowa Section 633.238 (2005)), the deceased spouse leaves a will which expressly devises the marital home to someone other than the surviving spouse. The surviving spouse may elect, contrary to the intent of the will, to live in the home for the remainder of his/her lifetime. This is called a "life estate" and terminates immediately upon the surviving spouse's death.

The historical and social policy purposes of such statutes are to assure that the surviving spouse receives a statutorily set minimum amount of property from the decedent. Historically, these statutes were enacted to prevent the deceased spouse from leaving the survivor destitute, thereby shifting the burden of care to the social welfare system.

In New York, a surviving spouse is entitled to one-third of her deceased spouse's estate. The decedent's debts, administrative expenses and reasonable funeral expenses are paid prior to the calculation of the spousal elective share. The elective share is calculated through the "net estate." The net estate is inclusive of property that passed by the laws of intestacy, testamentary property, and testamentary substitutes, as enumerated in EPTL 5-1.1-A. New York's classification of testamentary substitutes that are included in the net estate make it challenging for a deceased spouse to disinherit his or her surviving spouse.

Notable wills

In antiquity, Julius Caesar's will naming his grand-nephew Octavian as his adopted son and heir funded and legitimized his rise to political power in the late Republic, providing him the resources necessary to win the civil wars against the "Liberators" and Antony and to establish the Roman Empire under the name Augustus. Antony's officiating at the public reading of the will led to a riot and moved public opinion against Caesar's assassins. Octavian's illegal publication of Antony's sealed will was an important factor in removing his support within Rome, as it described his wish to be buried in Alexandria beside the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

In the modern era, the Thellusson v Woodford will case led to British legislation against the accumulation of money for later distribution and was fictionalized as Jarndyce and Jarndyce in Dickens's Bleak House. The Nobel Prizes were established by Alfred Nobel's will. Charles Vance Millar's will provoked the Great Stork Derby, as he successfully bequeathed the bulk of his estate to the Toronto-area woman who had the greatest number of children in the ten years after his death. (The prize was divided among four women who had nine, with smaller payments made to women who had borne 10 children but lost some to miscarriage. Another woman who bore ten children was disqualified as several were illegitimate.)

The longest known legal will is that of Englishwoman Frederica Evelyn Stilwell Cook. Probated in 1925, it was 1,066 pages, and had to be bound in 4 volumes; her estate was worth $100,000. The shortest known legal wills are those of Bimla Rishi of Delhi, India ("all to son") and Karl Tausch of Hesse, Germany, ("all to wife") both containing only two words in the language they were written in (Hindi and Czech respectively)[10] The shortest will is of Shripad Krishnarao Vaidya of Nagpur, Maharashtra consisting 5 letters as, “HEIR'S”.[11][12]

Probate

After the testator has died, an application for probate may be made in a court with probate jurisdiction to determine the validity of the will or wills that the testator may have created, i.e., which will satisfy the legal requirements, and to appoint an executor. In most cases, during probate, at least one witness is called upon to testify or sign a "proof of witness" affidavit. In some jurisdictions, however, statutes may provide requirements for a "self-proving" will (must be met during the execution of the will), in which case witness testimony may be forgone during probate. Often there is a time limit, usually 30 days, within which a will must be admitted to probate. Only an original will can be admitted to probate in the vast majority of jurisdictions – even the most accurate photocopy will not suffice.[citation needed] Some jurisdictions will admit a copy of a will if the original was lost or accidentally destroyed and the validity of the will can be shown to the court.[13]

If the will is ruled invalid in probate, then inheritance will occur under the laws of intestacy as if a will were never drafted.

See also

- Ademption

- Death and the internet, including password vaults

- Estate Planning

- Ethical will

- Legal history of wills

- Trust law

- Will aid

- Will contest

- Apertura tabularum

References

- ^ Wills, Trusts, and Estates (Aspen, 7th Ed., 2005)

- ^ Freedman, Adam (2013). The party of the first part the curious world of legalese. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 1466822570.

- ^ Eugene F. Scoles, Problems and Materials on Decedents' Estates and Trusts (2000), p. 39.

- ^ Chuck Stewart, Homosexuality and the Law: A Dictionary (2001), p. 310.

- ^ See also, for example, In Re Kaufmann's Will, 20 A.D.2d 464, 247 N.Y.S.2d 664 (1964), aff'd, 15 N.Y.2d 825, 257 N.Y.S.2d 941, 205 N.E.2d 864 (1965).

- ^ Louisiana Civil Code Article 1575 http://legis.la.gov/lss/lss.asp?doc=108900/

- ^ Text of the Washington Convention

- ^ a b Eskin, Vicki; Driscoll, Bryan. "Estate Planning with Foreign Property". American BAR Association. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ Sawyer, Antoinette. "How to Write a Will". FLD. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ World's smallest valid will ever

- ^ TARUN BHARAT (www.tarunbharat.net) Nagpur, Saturday, 28 April 2012

- ^ PUNNYA NAGARI (Marathi language daily published at Nagpur) Friday 8 June 2012

- ^ http://www.leg.state.nv.us/NRS/NRS-136.html#NRS136Sec230

Books

- Administration of Wills, Trusts, and Estates by Gordon W. Brown, Delmar Cengage Learning (ISBN 0-7668-5281-4) (ISBN 978-0-7668-5281-5)

External links

- Citizens Advice Bureau (UK)

- Wills of the Rich and Famous (Living Trust Network)

- Prerogative Court of Canterbury wills (1384–1858) at the National Archives (pay per view)

- Prerogative Court of Canterbury wills on thegenealogist.co.uk (subscription)

- Prerogative Court of Canterbury wills on Ancestry.co.uk (subscription)

- Download the wills of famous people (UK National Archives)

- William Shakespeare's Will

- Thomas Jefferson's Last Will

- Jane Austen's Will

- List of UK Regional Probate Registries - Regional Offices for probate information and to register the location of a Will and/or Executor