Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg | |

|---|---|

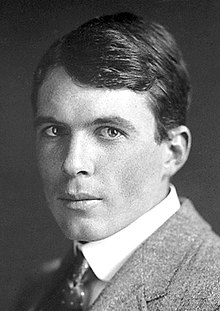

William L. Bragg in 1915 | |

| Born | 31 March 1890 Adelaide, South Australia |

| Died | 1 July 1971 (aged 81) Waldringfield, Ipswich, Suffolk, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | X-ray diffraction Bragg's law |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Academic advisors | |

| Doctoral students | |

| Notes | |

He was the son of W.H. Bragg. Note that the PhD did not exist at Cambridge until 1919, and so J. J. Thomson and W.H. Bragg were his equivalent mentors. | |

Sir William Lawrence Bragg CH, OBE, MC, FRS[1] (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structure. He was joint winner (with his father, William Henry Bragg) of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915: "For their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-ray",[3] an important step in the development of X-ray crystallography.

Bragg was knighted in 1941.[4] As of 2016, Lawrence Bragg is the youngest ever Nobel Laureate in physics, having received the award at the age of 25 years.[5] (The youngest of all Nobel Laureates is Malala Yousafzai in 2014 at the age of 17.) Bragg was the director of the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, when the discovery of the structure of DNA was reported by James D. Watson and Francis Crick in February 1953.

Biography

Early years

Bragg was born in Adelaide, South Australia. He showed an early interest in science and mathematics. His father, William Henry Bragg, was Elder Professor of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Adelaide. Shortly after starting school aged 5, William Lawrence Bragg fell from his tricycle and broke his arm. His father, who had read about Röntgen's experiments in Europe and was performing his own experiments, used the newly discovered X-rays and his experimental equipment to examine the broken arm. This is the first recorded surgical use of X-rays in Australia.

After beginning his studies at St Peter's College, Adelaide in 1905, Bragg went to the University of Adelaide at age 16 to study mathematics, chemistry and physics, graduating in 1908. In the same year his father accepted the Cavendish chair of physics at the University of Leeds, and brought the family back to England. Bragg entered Trinity College, Cambridge in the autumn of 1909 and received a major scholarship in mathematics, despite taking the exam while in bed with pneumonia. After initially excelling in mathematics, he transferred to the physics course in the later years of his studies, and graduated with first class honours in 1911. In 1914 Bragg was elected to a Fellowship at Trinity College – a Fellowship at a Cambridge college involves the submission and defence of a thesis.[6][7]

Among Bragg's other interests was shell collecting; his personal collection amounted to specimens from some 500 species; all personally collected from South Australia. He discovered a new species of cuttlefish – Sepia braggi, named for him by Joseph Verco.[8]

Career

Work on X-ray crystallography

Bragg is most famous for his law on the diffraction of X-rays by crystals. Bragg's law makes it possible to calculate the positions of the atoms within a crystal from the way in which an X-ray beam is diffracted by the crystal lattice. He made this discovery in 1912, during his first year as a research student in Cambridge. He discussed his ideas with his father, who developed the X-ray spectrometer in Leeds. This tool allowed many different types of crystals to be analysed.

Work on sound ranging

Bragg's research work was interrupted by both World War I and World War II. During both wars he worked on sound ranging methods for locating enemy guns. In this work he was aided by William Sansome Tucker, Harold Roper Robinson and Henry Harold Hemming. For his work during WWI he was awarded the Military Cross[9] and appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire.[10] He was also Mentioned in Despatches on 16 June 1916, 4 January 1917 and 7 July 1919.[11][12][13][14]

On 2 September 1915 his brother was killed during the Gallipoli Campaign.[15] Shortly afterwards, William Lawrence Bragg received the news that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, aged 25.[14]

Between the wars, from 1919 to 1937, he worked at the Victoria University of Manchester as Langworthy Professor of Physics. He was director of the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington in 1937.[16]

After World War II, Bragg returned to Cambridge, splitting the Cavendish Laboratory into research groups. He believed that "the ideal research unit is one of six to twelve scientists and a few assistants".

Work on proteins

In 1948 he became interested in the structure of proteins and was partly responsible for creating a group that used physics to solve biological problems. He played a part in the 1953 discovery of the structure of DNA, in that he provided support to Francis Crick and James D. Watson who worked under his aegis at the Cavendish.

Bragg's original announcement of the discovery of the structure of DNA was made at a Solvay conference on proteins in Belgium on 8 April 1953, but went unreported by the press. He then gave a talk at Guys Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday 14 May 1953, which resulted in an article by Ritchie Calder in The News Chronicle of London on Friday 15 May 1953, entitled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life."

Bragg was gratified to see that the X-ray method that he developed forty years before was at the heart of this profound insight to the nature of life itself. At the same time at the Cavendish, Max Perutz was also doing his Nobel Prize–winning work on the structure of haemoglobin. Bragg subsequently successfully lobbied for, and nominated, Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins for the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Wilkins' share recognised the contribution made by researchers (using X-ray crystallography) at King's College London to the determination of the structure of DNA. Among those researchers was Rosalind Franklin, whose "photograph 51" showed that DNA was a double helix, not a triple helix as Linus Pauling had proposed. Franklin died before the prize (which only goes to living people) was awarded.

The crystal structure of hen egg white lysozyme, which was solved by D C Phillips et al. in 1965[17] under the directorship of Lawrence Bragg at the Royal Institution, London, led to the discovery of the helix. The lysozyme structure was determined from crystals of hen egg white lysozyme chloride, which belong to the tetragonal space group P2 with the unit cell dimensions a = b = 79.1 Å, c = 37.9 Å and have one lysozyme molecule in the asymmetric unit.[17] The existence of the helix, as opposed to Pauling's alpha helix, was predicted by W L Bragg, J C Kendrew & M F Perutz in 1950.[18] Apparently, many workers failed to mention the discovery of the helix, and failed to acknowledge the part it plays in the lysozyme structure. Pauling never acknowledged that at least part of the above-mentioned 1950 paper made sense.

Unlike myoglobin, in which nearly 80 per cent of the amino-acid residues are in the alpha-helix conformation, in the lysozyme protein the alpha-helix content is only about 40 per cent of the amino-acid residues in four main stretches. The helix is an earlier proposal for the structure of polypeptides made by Bragg W L, Kendrew J C & Perutz M F in 1950. It is based on the crystallographic idea of an integral number of residues per turn of the helix. In this conformation, every third peptide is hydrogen-bonded back to the first peptide, thus forming a ring containing ten atoms.[19]

Royal Institution

He had a long association with the Royal Institution including:

- Professor of Natural Philosophy, 1938–1953

- Fullerian Professor of Chemistry, 1954–1966

- Superintendent of the House, 1954–1966

- Director of the Davy-Faraday Research Laboratory, 1954–1966

- Director, 1965–1966

- Emeritus Professor, 1966–1971

In 1931, 1934 and 1961 Bragg was invited to deliver the Royal Institution Christmas Lecture on The Universe of Light, Electricity and Electricity. He also introduced the Schools' Lectures Program during his time at the Royal Institution.[20]

Personal life

He married Alice Hopkinson (1899–1989) in 1921, with whom he had four children, Stephen Lawrence (1923–2014), David William (1926–2005), Margaret Alice, born 1931, (who married Mark Heath) and Patience Mary, born 1935. Alice was on the staff at Withington Girls' School until Bragg was appointed director of the NPL in 1937.[16]

Bragg's hobbies included painting, literature and a lifelong interest in gardening.[21] When he moved to London, he missed having a garden and so worked as a part-time gardener, unrecognised by his employer, until a guest at the house expressed surprise at seeing him there.[22] He died at a hospital near his home at Waldringfield, Ipswich, Suffolk. He was buried in Trinity College, Cambridge; his son David is buried in the Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge, where Bragg's friend Rudolph Cecil Hopkinson is also buried.

Honours and awards

Bragg was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1921[1]—"a qualification that makes other ones irrelevant".[23] He was knighted by King George VI in the 1941 New Year Honours,[24] and received both the Copley Medal and the Royal Medal of the Royal Society. Although Hunter, in his book on Bragg Light is a Messenger, argued that he was more a crystallographer than a physicist, Bragg's lifelong activity showed otherwise—he was more of a physicist than anything else. Thus, from 1939 to 1943, he served as President of the Institute of Physics, London.[25] In the 1967 New Year Honours he was appointed Companion of Honour by Queen Elizabeth II.[26]

Since 1992, the Australian Institute of Physics has awarded the Bragg Gold Medal for Excellence in Physics[27] to commemorate Lawrence Bragg (in front on the medal) and his father, William Bragg, for the best PhD thesis by a student at an Australian university.

- Nobel Prize (1915)

- Matteucci Medal (1915)

- Hughes Medal (1931)

- Royal Medal (1946)

- Guthrie Lecture (1952)

- Copley Medal (1966)

See also

References

- ^ a b c Phillips, D. (1979). "William Lawrence Bragg. 31 March 1890-1 July 1971". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 25: 74–26. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1979.0003. JSTOR 769842.

- ^ "Alexander Stokes". The Telegraph. 28 February 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1915". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ "Nobel Prizes and Laureates, Lawrence Bragg – Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Physics". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Cambridge physicists www.cambridgephysics.org

- ^ See Fred Hoyle's remarks regarding Hutchinson in 1965 Galaxies, Nuclei and Quasars p38 London:Heinemann and also R J N Phillips 1987 "Some Words from a Former Student" in Tribute to Paul Dirac, Bristol:Adam Hilger, p. 31.

- ^ Jenkin, John William and Lawrence Bragg; Father and Son. Oxford University Press 2008 ISBN 978 0 19 923520 9

- ^ "No. 30450". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 1 January 1918. MC - ^ "No. 30576". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 15 March 1918. OBE - ^ "No. 29623". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 13 June 1916. mid - ^ "No. 29890". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 2 January 1917. mid - ^ "No. 31437". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 4 July 1919. mid - ^ a b William Van der Kloot, Lawrence Bragg's role in the development of sound-ranging in World War I, Notes and Records of the Royal Society, 22 September 2005, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 273–284.

- ^ "Casualty Details: Bragg, Robert Charles". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ a b Newsletter 1936-1937. Withington Girls' School. 1937.

- ^ a b CCF Blake, DF Keonig, GA Mair, ACT North, DC Phillips & VR Sarma, Structure of Hen Egg-White Lysozyme: A Three-dimensional Fourier Synthesis at 2 Å Resolution. (1965) Nature 206:757–761

- ^ 1950 "Polypeptide chain configurations in crystalline proteins" Proc Roy A 203, p321

- ^ L N Johnson (1966) “The structure and function of lyszoyme” Sci Prog 54, p367

- ^ http://www.rigb.org/our-history/people/b/william-lawrence-bragg

- ^ Thomson, Patience (2013). "A tribute to W. L. Bragg by his younger daughter" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica Section A. A69: 5–7. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Crick, Francis (1989). What Mad Pursuit. Weidenfeld & Nicholson. p. 53. ISBN 0140119736.

- ^ G K Hunter 2004 Light is a Messenger Oxford:OUP

- ^ "No. 35029". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 31 December 1940. Knight bachelor - ^ http://www.cambridgephysics.org

- ^ "No. 44210". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 30 December 1966. CH - ^ Bragg Gold Medal for Excellence in Physics

Further reading

- Biography: Hunter, Graeme. Light Is A Messenger, the Life and Science of William Lawrence Bragg, ISBN 0-19-852921-X; Oxford University Press, 2004.

- John Finch; A Nobel Fellow On Every Floor, Medical Research Council 2008, 381 pp, ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0; (This book is about the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge.)

- Ridley, Matt; Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code (Eminent Lives), first published in July 2006 in the United States, and then in the UK in September 2006, by HarperCollins Publishers; 192 pp, ISBN 0-06-082333-X (This short book is in the publisher's "Eminent Lives" series).

- John Jenkin: "William and Lawrence Bragg, Father and Son: The Most Extraordinary Collaboration in Science", Oxford University Press, 2008.

External links

Media related to William Lawrence Bragg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Lawrence Bragg at Wikimedia Commons- First press stories on DNA

- Nobelprize.org – The Nobel Prize for Physics in 1915

- Nobel Biography

- A collection of digitised materials related to Bragg's and Linus Pauling's structural chemistry research.

- Key Participants: Sir William Lawrence Bragg – Linus Pauling and the Race for DNA: A Documentary History

- NOVA Episode on Photograph 51

- Oral History interview transcript with William Lawrence Bragg 20 June 1969, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- Bragg, Lawrence (Sir) (1890–1971) National Library of Australia, Trove, People and Organisation record for William Lawrence Bragg

- The Nature of Things: Oil, Soap and Detergent, Ri Channel video, November 1959

- The Nature of Things: Atoms and Molecules, Ri Channel video, October 1959

- The Nature of Things: Solids, Liquids and Gases, Ri Channel video, November 1959

- Use dmy dates from February 2012

- 1890 births

- 1971 deaths

- 20th-century physicists

- Academics of the Victoria University of Manchester

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Australian Nobel laureates

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- Australian people of English descent

- Australian physicists

- English physicists

- Experimental physicists

- Optical physicists

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Australian Knights Bachelor

- Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Australian Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People from Adelaide

- People from Ipswich

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Australian recipients of the Military Cross

- Royal Medal winners

- University of Adelaide alumni

- People educated at St Peter's College, Adelaide

- Presidents of the Institute of Physics

- X-ray crystallography

- Crystallographers

- English Nobel laureates

- Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Foreign Fellows of the Indian National Science Academy