Backmasking

Backmasking (also known as backward masking)[1] is a recording technique in which a sound or message is recorded backward on to a track that is meant to be played forward. Backmasking is a deliberate process, whereas a message found through phonetic reversal may be unintentional.

Backmasking was popularized by The Beatles, who used backward instrumentation on their 1966 album Revolver.[2] Artists have since used backmasking for artistic, comedic and satiric effect, on both analog and digital recordings. The technique has also been used to censor words or phrases for "clean" releases of rap songs.

Backmasking has been a controversial topic in the United States since the 1980s, when allegations from Christian groups of its use for Satanic purposes were made against prominent rock musicians, leading to record-burning protests and proposed anti-backmasking legislation by state and federal governments.[3]

History

Development

In 1877 Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, a device allowing sound to be recorded and reproduced on a rotating cylinder with a stylus (or "needle") attached to a diaphragm mounted at the narrow end of a horn. Emile Berliner invented the familiar lateral-cut disc phonograph record in 1888. His design overtook the Edison phonograph in the 1920s, since Berliner's patent expired in 1918, and others were then free to use his invention.

In addition to recreating recorded sounds by placing the stylus on the cylinder or disc and rotating it in the same direction as during the recording, one could hear different sounds by rotating the cylinder or disc backwards.[4] In 1878 Edison noted that, when played backwards, "the song is still melodious in many cases, and some of the strains are sweet and novel, but altogether different from the song reproduced in the right way".[5] The backwards playing of records was advised as training for magicians by occultist Aleister Crowley, who suggested in his 1913 book Magick (Book 4) that an adept "train himself to think backwards by external means", one of which was to "listen to phonograph records, reversed."[6]

The 1950s saw two new developments in audio technology: the development of musique concrète, an avant-garde form of electronic music which involves editing together fragments of natural and industrial sounds; and the concurrent spread of the use of tape recorders in recording studios.[7] These two trends led to tape music compositions, composed on tape using techniques including reverse tape effects.[8]

The Beatles, who incorporated the techniques of concrète into their recordings, were responsible for popularizing the concept of backmasking.[2] Singer John Lennon and producer George Martin both claimed they discovered the backward recording technique during the recording of 1966's Revolver; specifically the album tracks "Tomorrow Never Knows" and "I'm Only Sleeping," and the single "Rain".[9] Lennon stated that, while under the influence of marijuana, he accidentally played the tapes for "Rain" in reverse, and enjoyed the sound. The following day he shared the results with the other Beatles, and the effect was used first in the guitar solo for "Tomorrow Never Knows", and later in the coda of "Rain".[10][11] According to Martin, the band had been experimenting with changing the speeds of and reversing the "Tomorrow Never Knows" tapes, and Martin got the idea of reversing Lennon's vocals and guitar, which he did with a clip from "Rain". Lennon then liked the effect and kept it.[12][13] Regardless, "Rain" was the first song to feature a backmasked message: "Sunshine … Rain … When the rain comes, they run and hide their heads" (; the last line is the reversed first verse of the song).[14]

Rumors

The Beatles were involved in the spread of backmasking both as a recording technique and as the center of a controversy. The latter has its roots in an event in 1969, when WKNR-FM DJ Russ Gibb received a phone call from a student at Eastern Michigan University who identified himself as "Tom". The caller asked Gibb about a rumor that Beatle Paul McCartney had died, and claimed that the Beatles song "Revolution 9" contained a backward message confirming the rumor. Gibb played the song backwards on his turntable, and heard "Turn me on, dead man … turn me on, dead man … turn me on, dead man…" ().[15] Gibb began telling his listeners about what he called "The Great Cover-up",[16] and to the original clue were added various others, including the alleged backmasked message "Paul is a dead man, miss him, miss him, miss him", in "I'm So Tired".[15] The "Paul is dead" rumor popularized the idea of backmasking in popular music.[2]

After Gibb's show, many more songs were found to contain phrases that sounded like known spoken languages when reversed. Initially, the search was done mostly by fans of rock music; but, in the late 1970s,[17] during the rise of the Christian right in the United States,[18] fundamentalist Christian groups began to claim that backmasked messages could bypass the conscious mind and reach the subconscious, where they would be unknowingly accepted by the listener.[19] In 1981, Christian DJ Michael Mills began stating on Christian radio programs that Led Zeppelin's "Stairway to Heaven" contained hidden messages that were heard by the subconscious.[20] In early 1982, the Trinity Broadcasting Network's Paul Crouch hosted a show with self-described neuroscientist William Yarroll, who argued that rock stars were cooperating with the Church of Satan to place hidden subliminal messages on records.[21] Also in 1982, fundamentalist Christian pastor Gary Greenwald held public lectures on dangers of backmasking, along with at least one mass record-smashing.[22] During the same year, thirty North Carolina teenagers, led by their pastor, claimed that singers had been possessed by Satan, who used their voices to create backward messages, and held a record-burning at their church.[23]

Allegations of demonic backmasking were also made by social psychologists, parents and critics of rock music,[24] as well as the Parents Music Resource Center (formed in 1985),[25] which accused Led Zeppelin of using backmasking to promote Satanism.[26] On the April 28, 1982 edition of the CBS Evening News, Dan Rather discussed the finding of possible backmasked messages, and played reversed sections of songs by Led Zeppelin, Electric Light Orchestra, and Styx.[27]

Legislation

One result of the furor was the firing of five radio DJs who had encouraged listeners to search for backward messages in their record collections.[17] A more serious consequence was legislation by the state governments of Arkansas and California. The 1983 California bill was introduced to prevent backmasking that "can manipulate our behavior without our knowledge or consent and turn us into disciples of the Antichrist".[28] Involved in the discussion on the bill was a California State Assembly Consumer Protection and Toxic Materials Committee hearing, during which "Stairway to Heaven" was played backwards, and William Yaroll testified.[29] The successful bill made the distribution of records with undeclared backmasking an invasion of privacy for which the distributor could be sued.[22] The Arkansas law passed unanimously in 1983, referenced albums by The Beatles, Pink Floyd, Electric Light Orchestra, Queen and Styx,[18] and mandated that records with backmasking include a warning sticker: "Warning: This record contains backward masking which may be perceptible at a subliminal level when the record is played forward." However, the bill was returned to the state senate by Governor Bill Clinton and defeated.[22] House Resolution 6363, introduced in 1982 by Representative Bob Dornan (R-California), proposed mandating a similar label;[30] the bill was referred to the Subcommittee on Commerce, Transportation and Tourism and was never passed.[31] Government action was also called for in the legislatures of Texas and Canada.[22]

With the advent of compact discs in the 1980s, but prior to the advent of sound editing technology for personal computers in the 1990s, it became more difficult to listen to recordings backwards, and the controversy died down.[24]

Resurgence

Though the backmasking controversy peaked in the 1980s, the general belief in subliminal manipulation became more widespread in the United States during the following decade,[32] with belief in Satanic backmasking on records persisting into the 1990s.[33] At the same time, the development of sound editing software with audio reversal features simplified the process of reversing audio,[24] which previously could only be done with full fidelity using a professional tape recorder.[19] The Sound Recorder utility, included with Microsoft Windows from Windows 95 to Windows XP, allows one-click audio reversal,[34] as does popular open source sound editing software Audacity.[35] Following the growth of the Internet, backmasked message searchers used such software to create websites featuring backward music samples, which became a widely-used method of exploring backmasking in popular music.[24]

Use

Backmasking has been used as a recording technique since the 1960s. In the era of magnetic tape sound recording, backmasking required that the source reel-to-reel tape actually be played backwards, which was achieved by first being wound onto the original takeup reel, then reversing the reels so as to use that reel as the source (this would reverse the stereo channels as well). Digital audio recording has greatly simplified the process.[36]

Backmasked words are unintelligible noise when played forward, but when played backwards are clear speech.[23] Listening to backmasked audio with most turntables requires disengaging the drive and rotating the album by hand in reverse[37] (though some can play records backwards[19]). With magnetic tape, the tape must be reversed and spliced back in to the cassette.[37] Compact discs were difficult to reverse when first introduced, but digital audio editors, which were first introduced in the late 1980s and became popular during the next decade,[38] allow easy reversal of audio from digital sources.[24]

Satanic backmasking

Although the Satanic backmasking controversy involved mainly classic rock songs whose authors denied any intent to promote Satanism, backmasking has been used by heavy metal bands to deliberately insert messages in their lyrics or imagery. Bands have utilized Satanic imagery for commercial reasons.[39] For example, thrash metal band Slayer included at the start of the band's 1985 album Hell Awaits a deep backmasked voice chanting "Join Us" over and over.().[40] However, Slayer vocalist Tom Araya states that the band's use of Satanic imagery was "solely for effect".[41] Cradle of Filth, another band that has employed Satanic imagery, released a song entitled "Dinner at Deviant's Palace", consisting almost entirely of unusual sounds and a reversed reading of the Lord's Prayer[42] (a backwards reading of the Lord's Prayer is reportedly a major part of the Black Mass).[20][43] Seattle-based grunge band Soundgarden parodied the phenomenon of Satanic backmasking on their 1989 album Ultramega OK. When played backwards, the songs "665" and "667" reveal a song about Santa.

Aesthetic use

Backmasking is often used for aesthetics, i.e., to enhance the meaning or sound of a track.[17] During the Judas Priest subliminal message trial, lead singer Rob Halford admitted to recording the words "In the dead of the night, love bites" backwards into the track "Love Bites", from the 1984 album Defenders of the Faith. Asked why he recorded the message, Halford stated that "When you're composing songs, you're always looking for new ideas, new sounds."[44] Stanley Kubrick used "Masked Ball", an adaptation by Jocelyn Pook of her earlier work "Backwards Priests" (from the album Flood) featuring reversed Romanian chanting, as the background music for the masquerade ball scene in Eyes Wide Shut.[45]

One backmasking technique is to reverse an earlier part of a song. Missy Elliott used this technique in one of her songs, "Work It",[46] as did Jay Chou ("You Can Hear", from Ye Hui Mei),[47] At the Drive-In ("300 MHz", from Vaya),[48] and Lacuna Coil ("Self Deception", from Comalies).[49] A related technique is to reverse an entire instrumental track. John Lennon originally wanted to do so with "Rain", but objections by producer George Martin and bandmate Paul McCartney cut the backward section to 30 seconds.[10] The Stone Roses have made heavy use of this technique in songs including "Don't Stop",[50] "Guernica", and "Simone",[51] which are all backwards versions of other Stone Roses tracks, sometimes overdubbed with new vocals. Meanwhile, Klaatu used the reversed vocals from "Anus of Uranus" (from their first album, 3:47 EST) as the vocals for the song "Silly Boys" (on their third album, Sir Army Suit). The lyrics for "Silly Boys" on the lyric sheet from Sir Army Suit are accordingly printed backwards.[52] And Danish band Mew's 2009 album No More Stories... contains a track, "New Terrain", which, when listened to in reverse, reveals a new song, entitled "Nervous".[53]

Artists often use backmasking of sounds or instrumental audio to produce interesting sound effects.[36][54] One such sound effect is the reverse echo. When done on tape, such use of backmasking is known as reverse tape effects. One example is Matthew Sweet's 1999 album In Reverse, which includes reversed guitar parts which were played directly onto a tape running in reverse.[55] For live concerts, the guitar parts were played live on stage using a backward emulator.[56] The French House group Daft Punk released a song called "Funk Ad," which is a section of their single, "Da Funk," played backwards.

On the eponymous album Crosby, Stills and Nash, Stephen Stills' lead guitar in Pre-road Downs is heard in reverse through the entirety of the track.

Utada Hikaru uses backmasking in her hit 2005 song Passion, composed for the Kingdom Hearts II video game. When played backwards, eight instances of the message "I need more affection than you know" are revealed. "I need true emotions" is also hidden twice, as well as one "So many ups and downs".[citation needed]

Humorous and parody messages

A common use of backmasking is hiding a comedic or parodical message backwards in a song. The B-side of the 1966 Napoleon XIV single "They're Coming to Take Me Away Ha-Haaa!" is a reversed version of the entire forwards record, entitled "!aaaH-aH ,yawA eM ekaT oT gnimoC er'yehT". It reached #3 in the US charts, and #4 in the UK.[57]

Pink Floyd dropped a backmasked message into "Empty Spaces" (), from 1979's The Wall:

- ... Congratulations. You have just discovered the secret message. Please send your answer to Old Pink, care of the Funny Farm, Chalfont...

- Roger! Carolyne's on the phone!

- Okay.

The first line may refer to former lead singer Syd Barrett, who is thought to have suffered a nervous breakdown years earlier.[58]

In "Weird Al" Yankovic's "Nature Trail to Hell", from 1984's "Weird Al" Yankovic in 3-D, Yankovic's backmasked voice declares that "Satan eats Cheez Whiz" ().[24] Another early example can be found on the J. Geils Band track "No Anchovies, Please", from 1980s album Love Stinks. The message, disguised as a foreign-sounding language spoken under the narration, is, "It doesn't take a genius to tell the difference between chicken shit and chicken salad."[19] Belgian act Poesie Noire included a satirical backmasked message on their 1988 album Tetra saying "You fucking asshole, play the record in the normal way".[59] Tenacious D includes the backmasked message "Eat Donkey Crap" at the end of "Karate" from their self-titled first album.[60]

Electric Light Orchestra and Styx, following their involvement in the 1980s backmasking controversy, released songs that parody the allegations made against them. ELO, after being accused of Satanic backmasking on their 1974 album Eldorado, included backmasked messages in two songs on their next album, 1975's Face The Music.[61] "Down Home Town" begins with a voice twice repeating (in reverse) "Face the mighty waterfall".[62] And the opening instrumental "Fire On High" contains the backmasked message "The music is reversible, but time is not. Turn back! Turn back! Turn back! Turn back!" ().[63] In 1983 ELO released an entire album, Secret Messages, in response to the controversy.[64] Among the many backmasked messages on the album are: "Welcome to the big show" (2x);[19] "Thank you for listening"; "Look out there's danger ahead"; "Hup two three four"; "Time After Time"; and "You're playing me backwards".[62] Styx also released an album in response to allegations of Satanic backmasking:[65] 1983's Kilroy Was Here, which deals with an allegorical group called the "Majority for Musical Morality" that outlaws rock music.[18] A sticker on the album cover contains the message, "By order of the Majority for Musical Morality, this album contains secret backward messages", and the song "Heavy Metal Poisoning" does in fact contain the backmasked Latin words "Annuit Cœptis, Novus Ordo Seclorum" ("God has favored our undertakings; a new order for the ages")—part of the Great Seal which encircles the pyramid on the back of the American dollar bill.[30]

Iron Maiden's 1983 album Piece of Mind features a short backwards message, included by the band in response to allegations of Satanism that were surrounding them at the time.[66] Between the songs "The Trooper" and "Still Life" is inebriated drummer Nicko McBrain doing an impression of Idi Amin Dada: "'What ho', sed de t'ing wid de t'ree bonce [said the thing with the three heads]. Don't meddle wid t'ings you don't understand," followed by a belch.[67] Prince's controversial song "Darling Nikki" includes the backmasked message, "Hello, how are you? I am fine, because I know that the Lord is coming soon."[68] The Waitresses' 1982 EP I Could Rule the World if I Could Only Get the Parts included a backwards masking warning on the cover and a message masked within the song "The Smartest Person I Know": "Anyone who believes in backwards masking is a fool."

Some messages chastise or poke fun at the listener who is playing the song backwards. One such message was included by "Weird Al" Yankovic in "I Remember Larry", from the 1996 album Bad Hair Day, on which Yankovic lightly chastises the listener with the backmasked remark, "Wow, you must have an awful lot of free time on your hands" ().[69] Similarly, the B-52's song "Detour Through your Mind", from the 1986 LP Bouncing off the Satellites, contains the message, "I buried my parakeet in the backyard. Oh no, you're playing the record backwards. Watch out, you might ruin your needle."[70] Meanwhile, Christian rock group Petra included in their song "Judas Kiss", from the 1982 album More Power To Ya, the message, "What are you looking for the devil for, when you ought to be looking for the Lord?"[19] The band Mindless Self Indulgence released a song titled "Backmask", which contains the forward lyrics "Play that record backwards / Here's a message yo for the suckas / Play that record backwards / And go fuck yourself". The backwards messages in the song include, "clean your room", "do your homework", "don't stay out too late", and "eat your vegetables".[48][71]

Backmasking was also parodied in a 2001 episode of the television series The Simpsons entitled "New Kids on the Blecch." Bart Simpson joins a boy band called the Party Posse, whose song "Drop Da Bomb" includes the repeated lyric "Yvan eht nioj." Lisa Simpson becomes suspicious and plays the song backward, revealing the backmasked message "Join the Navy," which leads her to realize that the boy band was created as a subliminal recruiting tool for the United States Navy.

Critical or explicit messages

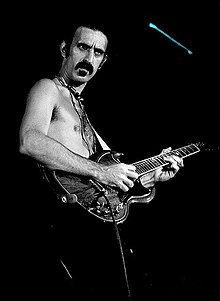

Backmasking has also been used to record statements perhaps too critical or explicit to be used forwards. Frank Zappa used backmasking to avoid censorship of the track "Hot Poop," from We're Only in It for the Money (1968). The released version contains at the end of its side "A" the backmasked message "Better look around before you say you don't care. / Shut your f...ing mouth 'bout the length of my hair. / How would you survive / If you were alive / shitty little person?" This profanity-laced verse, originally from the song "Mother People", was censored by Verve Records, so Zappa edited the verse out, reversed it, and inserted it elsewhere in the album as "Hot Poop" (though even in the backward message the word "fucking" is censored).[72] Another example is found in Roger Waters' 1991 album Amused to Death, on which Waters recorded a backward message, possibly critical of film director Stanley Kubrick, who had refused to let Waters sample a breathing sound from 2001: A Space Odyssey.[73] The message appears in the song "Perfect Sense Part 1", in which Waters' backmasked voice says, "Julia, however, in light and visions of the issues of Stanley, we have changed our minds. We have decided to include a backward message, Stanley, for you and all the other book burners."[74]

Censorship

A further use of backmasking is to censor words and phrases deemed inappropriate on radio edits and "clean" album releases.[75] For example, The Fugees' clean version of the album The Score contains various backmasked profanities;[75] thus, when playing the album backwards, the censored words are clearly audible among the backward gibberish.[76] When used with the word "shit", this type of backmasking results in a sound similar to "ish". As a result, "ish" became a euphemism for "shit".[77]

In Britney Spears' 2011 song "Till The World Ends" Spears says "if you want this good shit", on the official version "shit" is reversed creating the "ish" sound therefore the official version says "if you want this good ish". Backmasking is also used to censor the word "joint" in the video for "You Don't Know How It Feels" by Tom Petty, resulting in the line "Let's roll another tnioj".[78]

Accusations

Artists who have been accused of backmasking include Led Zeppelin,[79] The Beatles,[79] Pink Floyd,[79] Electric Light Orchestra,[79] Queen,[79] Styx,[79] AC/DC,[79] Judas Priest,[79] The Eagles,[79] The Rolling Stones,[79] Jefferson Starship,[30] Black Oak Arkansas,[30] Rush,[80] Britney Spears,[81] and Eminem.[24]

Electric Light Orchestra was accused of hiding a backward Satanic message in their 1974 album Eldorado. The title track, "Eldorado", was said to contain the message "He is the nasty one / Christ, you're infernal / It is said we're dead men / Everyone who has the mark will live."[30] ELO singer and songwriter Jeff Lynne responded by calling this accusation (and the related charge of being "devil-worshippers") "skcollob",[64] and stating that the message "is absolutely manufactured by whoever said, 'That's what it said.' It doesn't say anything of the sort."[70] The group included several backward messages in later albums in response to the accusations.

In 1981, Styx was accused of putting the backward message "Satan move through our voices" () on the song "Snowblind," from Paradise Theatre.[18] Guitarist James Young called these charges "rubbish,"[82] and responded, "If we want to make a statement, we'll do it in a way that people can understand us and not in a way where you have to go out and buy a $400 tape player to understand us."[65] In 1983, the band released a concept album, Kilroy Was Here, satirizing the Moral Majority.

A well-known alleged message is found in rock group Led Zeppelin's 1971 song "Stairway to Heaven." The backwards playing of a portion of the song purportedly results in words beginning with "Here's to my sweet Satan" ().[83] But Swan Song Records issued a statement to the contrary: "Our turntables only play in one direction—forwards".[20] And Led Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant denied the accusations in an interview: "To me it's very sad, because 'Stairway To Heaven' was written with every best intention, and as far as reversing tapes and putting messages on the end, that's not my idea of making music."[84] Another widely-known alleged message, "It's fun to smoke marijuana," in Queen's song "Another One Bites the Dust," is similarly disclaimed by the group's spokesperson.[24]

Subliminal persuasion

Accusations have been made by various groups that backmasking can be used to create subliminal messages.[citation needed]

Fundamentalist Christian groups

Various fundamentalist Christian groups have declared that Satan—or Satan-influenced musicians—use backmasked messages to subliminally alter behavior. Pastor Gary Greenwald claimed that subliminal messages backmasked into rock music induce listeners towards sex and drug use.[85] Minister Jacob Aranza wrote in his 1982 book Backward Masking Unmasked that rock groups "are using backmasking to convey satanic and drug related messages to the subconscious."[17] Christian DJ Michael Mills argued in 1981 that "the subconscious mind is being successfully affected by the repetition of beat and lyrics—being affected through a subliminal message."[86] Mills has toured America warning Christian parents about subliminal messages in rock music.[22]

Some Christian websites have claimed that backmasking is widely used for Satanic purposes.[23] The web page for Alabama group Dial-the-Truth Ministries argues for the existence of Satanic backmasking in "Stairway to Heaven," saying that the song contains the backward message, "It's my sweet Satan ... Oh I will sing because I live with Satan."[87]

PMRC

In 1985, Dr. Joe Stuessy testified to the United States Congress at the Parents Music Resource Center hearings that:

The message [of a piece of heavy metal music] may also be covert or subliminal. Sometimes subaudible tracks are mixed in underneath other, louder tracks. These are heard by the subconscious but not the conscious mind. Sometimes the messages are audible but are backward, called backmasking. There is disagreement among experts regarding the effectiveness of subliminals. We need more research on that.[88]

Stuessy's written testimony stated that:

Some messages are presented to the listener backwards. While listening to a normal forward message (often somewhat nonsensical), one is simultaneously being treated to a backwards message (in other words, the lyric sounds like one set of words going forward, and a different set of words going backwards). Some experts believe that while the conscious mind is absorbing the forward lyric, the subconscious is working overtime to decipher the backwards message.[88]

Court cases

Serial killer Richard Ramirez, on trial in 1988, stated that AC/DC's music, and specifically the song "Night Prowler" on Highway to Hell, inspired him to commit murder.[87] Reverse speech advocate David John Oates claimed that "Highway to Hell", on the same album, contains backmasked messages including "I'm the law", "my name is Lucifer", and "she belongs in hell".[89] AC/DC's Angus Young responded that "you didn't need to play [the album] backwards, because we never hid [the messages]. We'd call an album Highway To Hell, there it was right in front of them."[90]

In 1990, British heavy metal band Judas Priest was sued over a suicide pact made by two young men in Nevada. The lawsuit by their families claimed that the 1978 Judas Priest album Stained Class contained hidden messages, including the forward subliminal words "Do it" in the song "Better By You, Better Than Me" (ironically a cover version of a Spooky Tooth song), and various backward subliminal messages. The case was dismissed by the judge for insufficient evidence of Judas Priest's placement of subliminal messages on the record,[91] and the judge's ruling stated that "The scientific research presented does not establish that subliminal stimuli, even if perceived, may precipitate conduct of this magnitude. There exist other factors which explain the conduct of the deceased independent of the subliminal stimuli."[92] Judas Priest members commented that if they wanted to insert subliminal commands in their music, messages leading to the deaths of their fans would be counterproductive, and they would prefer to insert the command "Buy more of our records."[93]

Skepticism

Skeptic Michael Shermer claims that the emergence of the "Paul is dead" phenomenon, including the alleged message at the end of "I'm So Tired", was caused by faulty perception of a pattern. Shermer argues that the human brain evolved with a strong pattern recognition ability that was necessary to process the large amount of noise in man's environment, but that today this ability leads to false positives.[94] Stanford University psychology professor Brian Wandell postulates that the observance of backward messages is a mistake arising from this pattern recognition facility, and argues that subliminal persuasion theories are "bizarre" and "implausible."[37] Rumors of backmasking in popular music have been described as auditory pareidolia.[95] James Walker, president of Christian research group Watchman Fellowship, states that "You could take a Christian hymn, and if you played it backwards long enough at different speeds, you could make that hymn say anything you want to"; Led Zeppelin publicist BP Fallon concurs, saying "Play anything backwards, and you'll find something." Eric Borgos of audio reversal website talkbackwards.com[96] states that "Mathematically, if you listen long enough, eventually you'll find a pattern",[24] while Jeff Milner of backmasking site jeffmilner.com[83] recounts, "Most people, when I show them the site, say that they're not able to hear anything, until, of course, I show them the reverse lyrics."[97]

Audio engineer Evan Olcott claims that messages by artists including Queen and Led Zeppelin are coincidental phonetic reversals, in which the spoken or sung phonemes form new combinations of words when listened to backwards.[12] Olcott states that "Actually engineering or planning a phonetic reversal is next to impossible, and even more difficult when trying to design it with words that fit into a song."[25]

In 1985, University of Lethbridge psychologists John Vokey and J. Don Read conducted a study using Psalm 23 from the Bible, Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust", and other sound passages made up for the experiment. Vokey and Read concluded that if backmasking does exist, it is ineffective. Participants had trouble noticing backmasked phrases when the samples were played forwards, were unable to judge the types of messages (Christian, Satanic, or commercial), and were not led to behave in a certain way as a result of being exposed to the backmasked phrases. Vokey concluded that "we could find no effect of the meaning of engineered, backward messages on listeners' behaviour, either consciously or unconsciously."[98] Similar results to Vokey and Read's were obtained by D. Averill in 1982.[99] A 1988 experiment by T.E. Moore found "no evidence that listeners were influenced, consciously or unconsciously, by the content of the backward messages."[32] In 1992, an experiment found that exposure to backward messages did not lead to significant changes in attitude.[100] Psychology professor Mark D. Allen says that "delivering subliminal messages via backward masking is totally and ridiculously impossible".[101]

The finding of backward Satanic messages has been explained as caused by the observer-expectancy effect. The Skeptic's Dictionary states that "you probably won't hear [backmasked] messages until somebody first points them out to you. Perception is influenced by expectation and expectation is affected by what others prime you for."[102] In 1984, S. B. Thorne and P. Himelstein found that "when vague and unfamiliar stimuli are presented, [test subjects] are highly likely to accept suggestions, particularly when the suggestions are presented by someone with prestige and authority."[103] Vokey and Read concluded from their 1985 experiment that "the apparent presence of backward messages in popular music is a function more of active construction on the part of the perceiver than of the existence of the messages themselves."[22]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Backward(s) masking has two other meanings; see backward masking. See also Crispen, Bob. "Backward Masking … another pious fraud". The Crispen Family. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ a b c Sullivan, Mark (1987). "'More Popular Than Jesus': The Beatles and the Religious Far Right". Popular Music. 6 (3): 313–326. doi:10.1017/S0261143000002348.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Billiter, Bill (April 28, 1982). "Satanic Messages Played Back for Assembly Panel". Los Angeles Times, page B3.

- ^ Kittler, Friedrick. "The Gramaphone". Adventures in CyberSound. Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ Blecha, 48

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (1997) [1913]. Magick (Book 4). Weiser. p. 648. ISBN 0-87728-919-0.

- ^ White, Ray. "Musique Concrète". whitefiles.org. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Peters, Michael. "The Birth of Loop: A Short History of Looping Music". loopers-delight.com. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ Mugan, Chris (October 13, 2006). "Subliminal advertising: The voice within". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ a b Stevens, John (2002). The Songs of John Lennon: The Beatles Years. Berklee Press. pp. 149, 155–156. ISBN 0-634-01795-0.

- ^ Aldridge, Alan (1991). The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics. Houghton Mifflin. p. 135. ISBN 0-395-59426-X.

On the end of 'Rain' you hear me singing it backwards. We'd done the main thing at EMI and the habit was then to take the song home and see what you thought a little extra gimmick or what the guitar piece would be. So I got home about five in the morning, stoned out of my head, I staggered up to my tape recorder and I put it on, but it came out backwards, and I was in a trance in the earphones, what is it, what is it. It's too much, you know, and I really wanted the whole song backwards almost, and that was it. So we tagged it on the end.

- ^ a b Olcott, Evan. "Audio Reversal In Popular Culture". Triplo Press. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Giuliano, Geoffrey (1999). Glass Onion: The Beatles in their own words. Da Capo Press. p. 265. ISBN 0-306-80895-1.

I'd introduced John to backwards music on 'Rain' when I took his voice and turned it 'round when he was out on a coffee break. When I played it for him, he flipped.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cross, Craig (2005). The Beatles: Day-by-Day, Song-by-Song, Record-by-Record. New York: iUniverse. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-595-34663-9.

- ^ a b Reeve, Andru J. Turn Me On, Dead Man: The Beatles And The "Paul-Is-Dead" Hoax. AuthorHouse. pp. 11–13.

- ^ Yoakum, Jim (2000). "The Man Who Killed Paul McCartney". The Gadfly. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Blecha, 49

- ^ a b c d Holden, Stephen (1983-03-27). "Serious Issues Underlie a New Album from Styx". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Poundstone (1986), 227–232

- ^ a b c Davis, Erik (2007). "Led Zeppelin IV". In David Barker (ed.). 33 1/3 Greatest Hits, Volume One. Continuum. pp. 212–214. ISBN 0-8264-1903-8.

- ^ Denisoff, 289

- ^ a b c d e f Vokey, John R. (1985). "Subliminal messages: Between the devil and the media". American Psychologist. 40: 1231–1239. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1231. PMID 4083611.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Robinson, B. A. "Backmasking on records: Real, or hoax?". Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Searcey, Dionne (2006-01-09). "Behind the Music: Sleuths Seek Messages In Lyrical Backspin". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ a b Olcott, Evan. "Backwards Messages". Music and Technology. Triplo Press. Archived from the original on 2006-11-22. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Cox, Edward. "Popular music restrictions in America in the late 1980s/early 90s". edcox.net. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ Patterson, 173

- ^ Blecha, 51

- ^ Denisoff, 290

- ^ a b c d e Poundstone (1983), 200–214

- ^ H.R. 6363 from THOMAS

- ^ a b Brannon, Laura A.; Brock, Timothy C. "The Subliminal Persuasion Controversy: Reality, Enduring Fable, and Polonius's Weasel". In Shavitt, Sharon; Brock, Timothy C. (April 26, 1994). Persuasion: Psychological Insights and Perspectives (PDF). Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-15143-4.

- ^ Racocy, Rudolf E. (1992). "Introduction: The Importance of Music to People". In Kenneth J. Bindas (ed.). America's Musical Pulse: Popular Music in Twentieth-Century Society. Praeger. pp. xvi–xvii. ISBN 0-275-94306-2.

- ^ "Help with Windows Sound Recorder". Capital Community College. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Audacity: Features". SourceForge.net. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ^ a b Molitorisz, Sacha (June 23, 2004). "Out of the box". Radar Blog. Sidney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ a b c Holguin, Jaime (February 27, 2006). "Backmasking unmasked! Music site's in heavy rotation". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ "Portable Digital Audio Workstations (Buyer's Guide)". Theatre Crafts International. 1997-02-01. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Blecha, 52

- ^ "Slayer – Hell Awaits". UGO Networks. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ Hellqvist, Janek (1998-12-03). "Slayer FAQ". Slyer: The Abyss. slaytonic.com. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

Interview question: 'Did you adopt the satanic image solely for effect?' Tom: 'Yeah…'

- ^ Corbin, Dean. "Hard Rock/Metal/Punk". Backmask Online. Archived from the original on August 19, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fuller, Thomas (1863). Good Thoughts in Bad Times, and Other Papers. Ticknor and Fields. p. 157. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

Witches are reported (amongst many other hellish observations, whereby they oblige themselves to Satan) to say the Lord's prayer backwards.

- ^ "Judas Priest's Lead Singer Testifies". New York Times. August 1, 1990. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ Zwerin, Mike (October 27, 1999). "Kubrick's Approval Sets Seal on Classical Crossover Success: Pook's Unique Musical Mix". International Herald Tribune. Paris. Retrieved 2009-08-01. [dead link]

- ^ Corbin, Dean. "Rap/Hip Hop". Backmask Online. Archived from the original on March 11, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ "Jay Chou FAQ". Jay-Chou.net. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

- ^ a b Corbin, Dean. "Modern Rock". Backmask Online. Archived from the original on May 26, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ "Lacuna Coil—Frequently Asked Questions". Emptyspiral.net—The Lacuna Coil Community. October 12, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ Pomroy, Matt (October 22, 2002). "The Stone Roses: self-titled". PopMatters. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Brown, Ian (February 2, 1999). (Interview). Interviewed by Adam Walton http://adamwalton.co.uk/mmt_arc/int-ianbrown.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite interview}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bradley, David (January 24, 2004). "Klaatu Identities and Beatles Rumors". The Official Klaatu Homepage. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ "New Terrain / Nervous". MewX. July 28, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ^ Federlein, David (April 1, 2005). "Reader comments: backwards satanic messages". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ Simons, David (2000). "Matthew Sweet: Rebuilding the Wall of Sound". Guitar Player.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Simons, David (2000). "Back on the Bus". Onstage.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "They're Coming To Take Me Away, Ha-haaa by Napoleon XIV". Songfacts. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ Patterson, 186

- ^ http://www.poesienoire.com/php/matrix.php?action=listall

- ^ Marshall, Steve (2001). "Tenacious D: Tenacious D (Epic)". The Night Owl. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ Michel, Rob (2002). "1974: Electric Light Orchestra: Eldorado". Counting Out Time. Dutch Progressive Rock Page. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Secret Messages". My Electric Light Orchestra Fan Site. FutureBright. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- ^ Patterson, 173–174

- ^ a b "Electric Light Orchestra Biogs". Face The Music. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ a b Hoekstra, Dave (April 1, 1983). "Styx makes a statement". Suburban Sun-Times. Chicago.

- ^ Narinian, Vartan. "The Iron Maiden FAQ Part 1".

- ^ "The Iron Maiden Commentary". Archived from the original on August 23, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Prince – Darling Nikki". UGO Networks. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ Lick, Marty "Gumby". ""Weird Al" Yankovic Frequently Asked Questions". Al-oholics Anonymous. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Patterson, 174

- ^ "Mindless Self Indulgence – Backmask". UGO Networks. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ Pacholski, Luke. "We're Only In It for the Money". lukpac.org. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ Simon, Michael. "Amused To Death Trivia". Roger Waters International Fan Club. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "Roger Waters – Perfect Sense". UGO Networks. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ a b Nelson, Chris (1998-09-08). "Sticker Ban Policy: Family Values Or Consumer Fraud?". VH1. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ^ mcc. "Music that sounds better backward than forward". Everything2. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ Rader, Walter (2002-12-22). "The Online Slang Dictionary". University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Considine, J. D. (July 5, 1995). "Some lyrics are revised when listeners read between the lines Changing Their Tunes". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Blecha, 50

- ^ Deusner, Stephen M (December 12, 2005). "For Whom Hell's Bells Toll". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Tetley, Deborah (January 10, 2006). "Albertan finds Satan in music downloads". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ Arar, Yardena (May 26, 1982). "Satanic records or balderdash: Just what the devil's going on?". The Daily Herald. Arlington Heights, IL.

- ^ a b Milner, Jeff. "Jeff Milner's Backmasking Site". jeffmilner.com. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Plant, Robert (1983). "Life In A Lighter Zeppelin" (Interview). Interviewed by J.D. Considine. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|subjectlink=ignored (|subject-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Vokey, 248

- ^ Mills, Michael. Hidden and Satanic Messages In Rock Music. Radio interview, 1981, blog.wfmu.org. Introduction, at 1:22

- ^ a b Watkins, Terry. "Rock Music: The Devil's Advocate". Dial-the-Truth Ministries. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ a b United States Senate (1985). Record Labeling: Hearing before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. United States Senate, Ninety-ninth Congress, First Session on Contents of Music and the Lyrics of Records (September 19, 1985). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Pages 118–125. Available at Joesapt.net. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ Von Ulrich, Meyerratken (June 1997). Untitled. Esotera. Translated from German by Evan Galbraith. Edited by Michael George. Available at reversespeech.com. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Young, Angus; Young, Malcolm (2004). "AC/DC Celebrate Their Quarter Century" (Interview). Interviewed by Sylvie Simmons.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|program=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|subjectlink2=ignored (|subject-link2=suggested) (help) - ^ Vokey, 250

- ^ Sophia, Cassiel. "Subliminal Suicide?". Metareligion. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Van Taylor, David. KNPB Channel 5 Public Broadcasting, 1982: Dream Deceivers: The Story Behind James Vance Vs. Judas Priest.

- ^ Shermer, Michael (2005). "Turn Me On, Dead Man". Scientific American. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zusne, 77

- ^ Backmasking and Reverse Speech. TalkBackwards.com. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Hopper, Tristin (January 26, 2006). "Student sets up "backmasking" website". The Charlatan. Carleton University, Ottawa. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ Vokey, 249

- ^ Averill, D. (September 12, 1982). "Did the Devil make you do it?". Tulsa World. Oklahoma. p. 17. Cited in Zusne, 79

- ^ Swart, L.C. (1992). "Effects of subliminal backward-recorded messages on attitudes". Perceptual & Motor Skills. 75 (3 Pt 2): 1107–1113. doi:10.2466/PMS.75.8.1107-1113. PMID 1484773.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Glover, Melanie (January 19, 2006). "Backmasking: Satan, marijuana and Cheez Whiz". The California Aggie. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (December 28, 2006). "backwards satanic messages (backmasking)". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ Thorne, Stephen B.; Himelstein, Philip (1984). "The role of suggestion in the perception of Satanic messages on rock-and-role recordings". Journal of Psychology: 245–248. Cited in Hicks, Robert D. (1991). In Pursuit of Satan: The Police And the Occult. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus. p. 306. ISBN 1-59102-219-3.

Bibliography

- Blecha, Peter (2004). Taboo Tunes: A History of Banned Bands and Censored Songs. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-792-7.

- Denisoff, R. Serge (1988). Inside MTV. Transaction. ISBN 0-88738-864-7.

- Patterson, R. Gary (2004). Take a Walk on the Dark Side: Rock and Roll Myths, Legends, and Curses. Fireside. ISBN 0-7432-4423-0.

- Poundstone, William (1983). "Secret Messages on Records". Big Secrets. New York City: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-04830-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) Chapter also available with commentary by Malinda McCall. - Poundstone, William (1986). "Backward Messages on Records". Bigger Secrets. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-45397-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Vokey, John R. (2002). "Subliminal Messages". Psychological Sketches (PDF) (6th ed.). Lethbridge, Alberta: Psyence Ink. pp. 223–246. Retrieved 2006-07-05.

- Zusne, Leonard (1989). Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 78. ISBN 0-8058-0508-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Backmasking—essay on backmasking & a small survey about perception of alleged satanic messages in the song "Stairway to Heaven" by Led Zeppelin

- Backmask Online—clips and analysis of possible backmasked messages

- Jeff Milner's Backmasking Page—a Flash player with forward and backward versions of songs claimed to contain backmasking; the focus of the Wall Street Journal article

- Backmask Flash—flash clips of possible backmasked messages from Albino Blacksheep

- Subliminal Audio Database— Another flash player with forward and backward versions of songs claimed to contain backmasking

- TalkBackwards.com—allows uploaded music to be reversed

- Hidden and Satanic Messages In Rock Music—1981 radio interview with Michael Mills

- Excerpt with alleged backward messages by Led Zeppelin, The Beatles, Queen

- "Backwards Messages in Rock Music—Revealed!" podcast featuring The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, Rush, Jefferson Starship, Wings, Queen, Phil Collins, Britney Spears, Judas Priest, Pink Floyd, Iron Maiden, Electric Light Orchestra, Prince and Information Society

- Radio program exploring backmasking by announcer Joe Kleon, broadcast on WRQK-FM, with audio samples from Britney Spears, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Metallica, Styx, Cheap Trick and others