Malaria: Difference between revisions

m move ref; ce & fmt |

→Mosquito control: added |

||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

[[File:Midnight in Pediatric ICU.jpg|thumb|Mosquito nets create a protective barrier against malaria-carrying mosquitoes that bite at night.]] |

[[File:Midnight in Pediatric ICU.jpg|thumb|Mosquito nets create a protective barrier against malaria-carrying mosquitoes that bite at night.]] |

||

Mosquito nets help keep mosquitoes away from people and reduce infection rates and transmission of malaria. Nets are not a perfect barrier and are often treated with an insecticide designed to kill the mosquito before it has time to find a way past the net. Insecticide-treated nets are estimated to be twice as effective as untreated nets and offer greater than 70% protection compared with no net.<ref name="Raghavendra 2011"/> Between 2000 and 2008, the use of ITNs saved the lives of an estimated 250,000 infants in Sub-Saharan Africa.<ref name="Howitt 2012"/> Although ITNs prevent malaria, only about 13% of households in Sub-Saharan countries own them.<ref name="Miller 2007"/> |

Mosquito nets help keep mosquitoes away from people and reduce infection rates and transmission of malaria. Nets are not a perfect barrier and are often treated with an insecticide designed to kill the mosquito before it has time to find a way past the net. Insecticide-treated nets are estimated to be twice as effective as untreated nets and offer greater than 70% protection compared with no net.<ref name="Raghavendra 2011"/> Between 2000 and 2008, the use of ITNs saved the lives of an estimated 250,000 infants in Sub-Saharan Africa.<ref name="Howitt 2012"/> Although ITNs prevent malaria, only about 13% of households in Sub-Saharan countries own them.<ref name="Miller 2007"/> A recommended practice for usage is to hang a large "bed net" above the center of a bed to drape over it completely with the edges tucked in. [[Pyrethroid]]-treated nets and long-lasting insecticide-treated nets offer the best personal protection, and are most effective when used from dusk to dawn.<ref>{{harvnb|Schlagenhauf-Lawlor|2008|pp=[http://books.google.com/books?id=54Dza0UHyngC&pg=PA215 215]}}</ref> |

||

There are other methods intended to reduce the |

There are a number of other methods intended to reduce mosquito bites and slow the spread of malaria. Efforts to decrease mosquito larva via decreasing the availability of open water in which they develop or by adding substances to decrease their development is effective in some locations.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tusting|first=LS|coauthors=Thwing, J; Sinclair, D; Fillinger, U; Gimnig, J; Bonner, KE; Bottomley, C; Lindsay, SW|title=Mosquito larval source management for controlling malaria.|journal=The Cochrane database of systematic reviews|date=2013 Aug 29|volume=8|pages=CD008923|pmid=23986463}}</ref> Electronic mosquito repellent devices which make very high frequency sounds that are supposed to keep female mosquitoes away, do not have supporting evidence.<ref name="Enayati 2007"/> |

||

===Other methods=== |

===Other methods=== |

||

Revision as of 00:19, 21 December 2013

| Malaria | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases, tropical medicine, parasitology |

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by parasitic protozoans (a type of unicellular microorganism) of the genus Plasmodium. Commonly, the disease is transmitted via a bite from an infected female Anopheles mosquito, which introduces the organisms from its saliva into a person's circulatory system. In the blood, the protists travel to the liver to mature and reproduce. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever and headache, which in severe cases can progress to coma or death. The disease is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions in a broad band around the equator, including much of Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Five species of Plasmodium can infect and be transmitted by humans. The vast majority of deaths are caused by P. falciparum and P. vivax, while P. ovale, and P. malariae cause a generally milder form of malaria that is rarely fatal. The zoonotic species P. knowlesi, prevalent in Southeast Asia, causes malaria in macaques but can also cause severe infections in humans. Malaria is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions because rainfall, warm temperatures, and stagnant waters provide habitats ideal for mosquito larvae. Disease transmission can be reduced by preventing mosquito bites by using mosquito nets and insect repellents, or with mosquito-control measures such as spraying insecticides and draining standing water.

Malaria is typically diagnosed by the microscopic examination of blood using blood films, or with antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests. Modern techniques that use the polymerase chain reaction to detect the parasite's DNA have also been developed, but these are not widely used in malaria-endemic areas due to their cost and complexity. The World Health Organization has estimated that in 2010, there were 219 million documented cases of malaria. That year, the disease killed between 660,000 and 1.2 million people,[1] many of whom were children in Africa. The actual number of deaths is not known with certainty, as accurate data is unavailable in many rural areas, and many cases are undocumented. Malaria is commonly associated with poverty and may also be a major hindrance to economic development.

Despite a need, no effective vaccine exists, although efforts to develop one are ongoing. Several medications are available to prevent malaria in travellers to malaria-endemic countries (prophylaxis). A variety of antimalarial medications are available. Severe malaria is treated with intravenous or intramuscular quinine or, since the mid-2000s, the artemisinin derivative artesunate, which is superior to quinine in both children and adults and is given in combination with a second anti-malarial such as mefloquine. Resistance has developed to several antimalarial drugs; for example, chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum has spread to most malarial areas, and emerging resistance to artemisinin has become a problem in some parts of Southeast Asia.

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of malaria typically begin 8–25 days following infection;[2] however, symptoms may occur later in those who have taken antimalarial medications as prevention.[3] Initial manifestations of the disease—common to all malaria species—are similar to flu-like symptoms,[4] and can resemble other conditions such as septicemia, gastroenteritis, and viral diseases.[3] The presentation may include headache, fever, shivering, joint pain, vomiting, hemolytic anemia, jaundice, hemoglobin in the urine, retinal damage, and convulsions.[5]

The classic symptom of malaria is paroxysm—a cyclical occurrence of sudden coldness followed by shivering and then fever and sweating, occurring every two days (tertian fever) in P. vivax and P. ovale infections, and every three days (quartan fever) for P. malariae. P. falciparum infection can cause recurrent fever every 36–48 hours or a less pronounced and almost continuous fever.[6]

Severe malaria is usually caused by P. falciparum (often referred to as falciparum malaria). Symptoms of falciparium malaria arise 9–30 days after infection.[4] Individuals with cerebral malaria frequently exhibit neurological symptoms, including abnormal posturing, nystagmus, conjugate gaze palsy (failure of the eyes to turn together in the same direction), opisthotonus, seizures, or coma.[4]

Complications

There are several serious complications of malaria. Among these is the development of respiratory distress, which occurs in up to 25% of adults and 40% of children with severe P. falciparum malaria. Possible causes include respiratory compensation of metabolic acidosis, noncardiogenic pulmonary oedema, concomitant pneumonia, and severe anaemia. Although rare in young children with severe malaria, acute respiratory distress syndrome occurs in 5–25% of adults and up to 29% of pregnant women.[7] Coinfection of HIV with malaria increases mortality.[8] Renal failure is a feature of blackwater fever, where hemoglobin from lysed red blood cells leaks into the urine.[4]

Infection with P. falciparum may result in cerebral malaria, a form of severe malaria that involves encephalopathy. It is associated with retinal whitening, which may be a useful clinical sign in distinguishing malaria from other causes of fever.[9] Splenomegaly, severe headache, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), hypoglycemia, and hemoglobinuria with renal failure may occur.[4]

Malaria in pregnant women is an important cause of stillbirths, infant mortality and low birth weight,[10] particularly in P. falciparum infection, but also with P. vivax.[11]

Cause

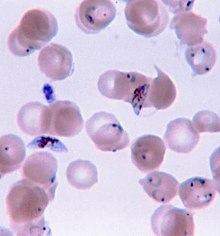

Malaria parasites belong to the genus Plasmodium (phylum Apicomplexa). In humans, malaria is caused by P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, P. vivax and P. knowlesi.[12][13] Among those infected, P. falciparum is the most common species identified (~75%) followed by P. vivax (~20%).[3] Although P. falciparum traditionally accounts for the majority of deaths,[14] recent evidence suggests that P. vivax malaria is associated with potentially life-threatening conditions about as often as with a diagnosis of P. falciparum infection.[15] P. vivax proportionally is more common outside of Africa.[16] There have been documented human infections with several species of Plasmodium from higher apes; however, with the exception of P. knowlesi—a zoonotic species that causes malaria in macaques[13]—these are mostly of limited public health importance.[17]

Life cycle

In the life cycle of Plasmodium, a female Anopheles mosquito (the definitive host) transmits a motile infective form (called the sporozoite) to a vertebrate host such as a human (the secondary host), thus acting as a transmission vector. A sporozoite travels through the blood vessels to liver cells (hepatocytes), where it reproduces asexually (tissue schizogony), producing thousands of merozoites. These infect new red blood cells and initiate a series of asexual multiplication cycles (blood schizogony) that produce 8 to 24 new infective merozoites, at which point the cells burst and the infective cycle begins anew.[18]

Other merozoites develop into immature gametocytes, which are the precursors of male and female gametes. When a fertilised mosquito bites an infected person, gametocytes are taken up with the blood and mature in the mosquito gut. The male and female gametocytes fuse and form a ookinete—a fertilized, motile zygote. Ookinetes develop into new sporozoites that migrate to the insect's salivary glands, ready to infect a new vertebrate host. The sporozoites are injected into the skin, in the saliva, when the mosquito takes a subsequent blood meal.[19]

Only female mosquitoes feed on blood; male mosquitoes feed on plant nectar, and thus do not transmit the disease. The females of the Anopheles genus of mosquito prefer to feed at night. They usually start searching for a meal at dusk, and will continue throughout the night until taking a meal.[20] Malaria parasites can also be transmitted by blood transfusions, although this is rare.[21]

Recurrent malaria

Symptoms of malaria can recur after varying symptom-free periods. Depending upon the cause, recurrence can be classified as either recrudescence, relapse, or reinfection. Recrudescence is when symptoms return after a symptom-free period. It is caused by parasites surviving in the blood as a result of inadequate or ineffective treatment.[22] Relapse is when symptoms reappear after the parasites have been eliminated from blood but persist as dormant hypnozoites in liver cells. Relapse commonly occurs between 8–24 weeks and is commonly seen with P. vivax and P. ovale infections.[3] P. vivax malaria cases in temperate areas often involve overwintering by hypnozoites, with relapses beginning the year after the mosquito bite.[23] Reinfection means the parasite that caused the past infection was eliminated from the body but a new parasite was introduced. Reinfection cannot readily be distinguished from recrudescence, although recurrence of infection within two weeks of treatment for the initial infection is typically attributed to treatment failure.[24]

Pathophysiology

Malaria infection develops via two phases: one that involves the liver (exoerythrocytic phase), and one that involves red blood cells, or erythrocytes (erythrocytic phase). When an infected mosquito pierces a person's skin to take a blood meal, sporozoites in the mosquito's saliva enter the bloodstream and migrate to the liver where they infect hepatocytes, multiplying asexually and asymptomatically for a period of 8–30 days.[25]

After a potential dormant period in the liver, these organisms differentiate to yield thousands of merozoites, which, following rupture of their host cells, escape into the blood and infect red blood cells to begin the erythrocytic stage of the life cycle.[25] The parasite escapes from the liver undetected by wrapping itself in the cell membrane of the infected host liver cell.[26]

Within the red blood cells, the parasites multiply further, again asexually, periodically breaking out of their host cells to invade fresh red blood cells. Several such amplification cycles occur. Thus, classical descriptions of waves of fever arise from simultaneous waves of merozoites escaping and infecting red blood cells.[25]

Some P. vivax sporozoites do not immediately develop into exoerythrocytic-phase merozoites, but instead produce hypnozoites that remain dormant for periods ranging from several months (7–10 months is typical) to several years. After a period of dormancy, they reactivate and produce merozoites. Hypnozoites are responsible for long incubation and late relapses in P. vivax infections,[23] although their existence in P. ovale is uncertain.[27]

The parasite is relatively protected from attack by the body's immune system because for most of its human life cycle it resides within the liver and blood cells and is relatively invisible to immune surveillance. However, circulating infected blood cells are destroyed in the spleen. To avoid this fate, the P. falciparum parasite displays adhesive proteins on the surface of the infected blood cells, causing the blood cells to stick to the walls of small blood vessels, thereby sequestering the parasite from passage through the general circulation and the spleen.[28] The blockage of the microvasculature causes symptoms such as in placental malaria.[29] Sequestered red blood cells can breach the blood–brain barrier and cause cerebral malaria.[30]

Genetic resistance

According to a 2005 review, due to the high levels of mortality and morbidity caused by malaria—especially the P. falciparum species—it has placed the greatest selective pressure on the human genome in recent history. Several genetic factors provide some resistance to it including sickle cell trait, thalassaemia traits, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and the absence of Duffy antigens on red blood cells.[31][32]

The impact of sickle cell trait on malaria immunity illustrates some of the evolutionary trade-offs that have occurred because of endemic malaria. Sickle cell trait causes a defect in the hemoglobin molecule in the blood. Instead of retaining the biconcave shape of a normal red blood cell, the modified hemoglobin S molecule causes the cell to sickle or distort into a curved shape. Due to the sickle shape, the molecule is not as effective in taking or releasing oxygen. Infection causes red cells to sickle more, and so they are removed from circulation sooner. This reduces the frequency with which malaria parasites complete their life cycle in the cell. Individuals who are homozygous (with two copies of the abnormal hemoglobin beta allele) have sickle-cell anaemia, while those who are heterozygous (with one abnormal allele and one normal allele) experience resistance to malaria. Although the shorter life expectancy for those with the homozygous condition would not sustain the trait's survival, the trait is preserved because of the benefits provided by the heterozygous form.[32][33]

Liver dysfunction

Liver dysfunction as a result of malaria is uncommon and is usually a result of a coexisting liver condition such as viral hepatitis or chronic liver disease. The syndrome is sometimes called malarial hepatitis.[34] While it has been considered a rare occurrence, malarial hepatopathy has seen an increase, particularly in Southeast Asia and India. Liver compromise in people with malaria correlates with a greater likelihood of complications and death.[34]

Diagnosis

Owing to the non-specific nature of the presentation of symptoms, diagnosis of malaria in non-endemic areas requires a high degree of suspicion, which might be elicited by any of the following: recent travel history, enlarged spleen, fever, low number of platelets in the blood, and higher-than-normal levels of bilirubin in the blood combined with a normal level of white blood cells.[3]

Malaria is usually confirmed by the microscopic examination of blood films or by antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests (RDT).[35][36] Microscopy is the most commonly used method to detect the malarial parasite—about 165 million blood films were examined for malaria in 2010.[37] Despite its widespread usage, diagnosis by microscopy suffers from two main drawbacks: many settings (especially rural) are not equipped to perform the test, and the accuracy of the results depends on both the skill of the person examining the blood film and the levels of the parasite in the blood. The sensitivity of blood films ranges from 75–90% in optimum conditions, to as low as 50%. Commercially available RDTs are often more accurate than blood films at predicting the presence of malaria parasites, but they are widely variable in diagnostic sensitivity and specificity depending on manufacturer, and are unable to tell how many parasites are present.[37]

In regions where laboratory tests are readily available, malaria should be suspected, and tested for, in any unwell patient who has been in an area where malaria is endemic. In areas that cannot afford laboratory diagnostic tests, it has become routine to use only a history of subjective fever as the indication to treat for malaria—a presumptive approach exemplified by the common teaching "fever equals malaria unless proven otherwise". A drawback of this practice is overdiagnosis of malaria and mismanagement of non-malarial fever, which wastes limited resources, erodes confidence in the health care system, and contributes to drug resistance.[38] Although polymerase chain reaction-based tests have been developed, these are not widely implemented in malaria-endemic regions as of 2012, due to their complexity.[3]

Classification

Malaria is classified into either "severe" or "uncomplicated" by the World Health Organization (WHO).[3] It is deemed severe when any of the following criteria are present, otherwise it is considered uncomplicated.[39]

- Decreased consciousness

- Significant weakness such that the person is unable to walk

- Inability to feed

- Two or more convulsions

- Low blood pressure (less than 70 mmHg in adults and 50 mmHg in children)

- Breathing problems

- Circulatory shock

- Kidney failure or hemoglobin in the urine

- Bleeding problems, or hemoglobin less than 50 g/L (5 g/dL)

- Pulmonary oedema

- Blood glucose less than 2.2 mmol/L (40 mg/dL)

- Acidosis or lactate levels of greater than 5 mmol/L

- A parasite level in the blood of greater than 100,000 per microlitre (µL) in low-intensity transmission areas, or 250,000 per µL in high-intensity transmission areas

Cerebral malaria is defined as a severe P. falciparum-malaria presenting with neurological symptoms, including coma (with a Glasgow coma scale less than 11, or a Blantyre coma scale greater than 3), or with a coma that lasts longer than 30 minutes after a seizure.[40]

Prevention

Methods used to prevent malaria include medications, mosquito elimination and the prevention of bites. The presence of malaria in an area requires a combination of high human population density, high anopheles mosquito population density and high rates of transmission from humans to mosquitoes and from mosquitoes to humans. If any of these is lowered sufficiently, the parasite will eventually disappear from that area, as happened in North America, Europe and parts of the Middle East. However, unless the parasite is eliminated from the whole world, it could become re-established if conditions revert to a combination that favours the parasite's reproduction. Furthermore, the cost per person of eliminating anopheles mosquitos rises with decreasing population density, making it economically unfeasible in some areas.[41]

Many researchers argue that prevention of malaria may be more cost-effective than treatment of the disease in the long run, but the capital costs required are out of reach of many of the world's poorest people. There is a wide difference in the costs of control (i.e. maintenance of low endemicity) and elimination programs between countries. For example, in China—whose government in 2010 announced a strategy to pursue malaria elimination in the Chinese provinces—the required investment is a small proportion of public expenditure on health. In contrast, a similar program in Tanzania would cost an estimated one-fifth of the public health budget.[42]

Mosquito control

Vector control refers to methods used to decrease malaria by reducing the levels of transmission. For individual protection, the most effective insect repellents are based on DEET or picaridin.[43] Insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) have been shown to be highly effective in preventing malaria among children in areas where malaria is common.[44][45]

IRS is the practice of spraying insecticides on the interior walls of homes in malaria-affected areas. After feeding, many mosquito species rest on a nearby surface while digesting the bloodmeal, so if the walls of houses have been coated with insecticides, the resting mosquitoes can be killed before they can bite another person and transfer the malaria parasite.[46] As of 2006, the World Health Organization recommends 12 insecticides in IRS operations, including DDT and the pyrethroids cyfluthrin and deltamethrin.[47] This public health use of small amounts of DDT is permitted under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), which prohibits its agricultural use.[48] One problem with all forms of IRS is insecticide resistance. Mosquitoes affected by IRS tend to rest and live indoors, and due to the irritation caused by spraying, their descendants tend to rest and live outdoors, meaning that they are less affected by the IRS.[49]

Mosquito nets help keep mosquitoes away from people and reduce infection rates and transmission of malaria. Nets are not a perfect barrier and are often treated with an insecticide designed to kill the mosquito before it has time to find a way past the net. Insecticide-treated nets are estimated to be twice as effective as untreated nets and offer greater than 70% protection compared with no net.[50] Between 2000 and 2008, the use of ITNs saved the lives of an estimated 250,000 infants in Sub-Saharan Africa.[51] Although ITNs prevent malaria, only about 13% of households in Sub-Saharan countries own them.[52] A recommended practice for usage is to hang a large "bed net" above the center of a bed to drape over it completely with the edges tucked in. Pyrethroid-treated nets and long-lasting insecticide-treated nets offer the best personal protection, and are most effective when used from dusk to dawn.[53]

There are a number of other methods intended to reduce mosquito bites and slow the spread of malaria. Efforts to decrease mosquito larva via decreasing the availability of open water in which they develop or by adding substances to decrease their development is effective in some locations.[54] Electronic mosquito repellent devices which make very high frequency sounds that are supposed to keep female mosquitoes away, do not have supporting evidence.[55]

Other methods

Community participation and health education strategies promoting awareness of malaria and the importance of control measures have been successfully used to reduce the incidence of malaria in some areas of the developing world.[56] Recognizing the disease in the early stages can stop the disease from becoming fatal. Education can also inform people to cover over areas of stagnant, still water, such as water tanks that are ideal breeding grounds for the parasite and mosquito, thus cutting down the risk of the transmission between people. This is generally used in urban areas where there are large centers of population in a confined space and transmission would be most likely in these areas.[57] Intermittent preventive therapy is another intervention that has been used successfully to control malaria in pregnant women and infants,[58] and in preschool children where transmission is seasonal.[59]

Medications

There are a number of drugs that can help prevent malaria while travelling in areas where it exists. Most of these drugs are also sometimes used in treatment. Chloroquine may be used where the parasite is still sensitive.[60] Because most Plasmodium is resistant to one or more medications, one of three medications—mefloquine (Lariam), doxycycline (available generically), or the combination of atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride (Malarone)—is frequently needed.[60] Doxycycline and the atovaquone and proguanil combination are the best tolerated; mefloquine is associated with death, suicide, and neurological and psychiatric symptoms.[60]

The protective effect does not begin immediately, and people visiting areas where malaria exists usually start taking the drugs one to two weeks before arriving and continue taking them for four weeks after leaving (with the exception of atovaquone/proguanil, which only needs to be started two days before and continued for seven days afterward).[61] The use of preventative drugs is seldom practical for those who reside in areas where malaria exists, and their use is usually only in short-term visitors and travellers. This is due to the cost of the drugs, side effects from long-term use, and the difficulty in obtaining anti-malarial drugs outside of wealthy nations.[62] The use of preventative drugs where malaria-bearing mosquitoes are present may encourage the development of partial resistance.[63]

Treatment

Malaria is treated with antimalarial medications; the ones used depends on the type and severity of the disease. While medications against fever are commonly used, their effects on outcomes are not clear.[64]

Uncomplicated malaria may be treated with oral medications. The most effective treatment for P. falciparum infection is the use of artemisinins in combination with other antimalarials (known as artemisinin-combination therapy, or ACT), which decreases resistance to any single drug component.[65] These additional antimalarials include: amodiaquine, lumefantrine, mefloquine or sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine.[66] Another recommended combination is dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine.[67][68] ACT is about 90% effective when used to treat uncomplicated malaria.[51] To treat malaria during pregnancy, the WHO recommends the use of quinine plus clindamycin early in the pregnancy (1st trimester), and ACT in later stages (2nd and 3rd trimesters).[69] In the 2000s (decade), malaria with partial resistance to artemisins emerged in Southeast Asia.[70][71] Infection with P. vivax, P. ovale or P. malariae is usually treated without the need for hospitalization. Treatment of P. vivax requires both treatment of blood stages (with chloroquine or ACT) as well as clearance of liver forms with primaquine.[72]

Recommended treatment for severe malaria is the intravenous use of antimalarial drugs. For severe malaria, artesunate is superior to quinine in both children and adults.[73] Treatment of severe malaria involves supportive measures that are best done in a critical care unit. This includes the management of high fevers and the seizures that may result from it. It also includes monitoring for poor breathing effort, low blood sugar, and low blood potassium.[14]

Prognosis

When properly treated, people with malaria can usually expect a complete recovery.[74] However, severe malaria can progress extremely rapidly and cause death within hours or days.[75] In the most severe cases of the disease, fatality rates can reach 20%, even with intensive care and treatment.[3] Over the longer term, developmental impairments have been documented in children who have suffered episodes of severe malaria.[76] Chronic infection without severe disease can occur in an immune-deficiency syndrome associated with a decreased responsiveness to Salmonella bacteria and the Epstein–Barr virus.[77]

During childhood, malaria causes anemia during a period of rapid brain development, and also direct brain damage resulting from cerebral malaria.[76] Some survivors of cerebral malaria have an increased risk of neurological and cognitive deficits, behavioural disorders, and epilepsy.[78] Malaria prophylaxis was shown to improve cognitive function and school performance in clinical trials when compared to placebo groups.[76]

Epidemiology

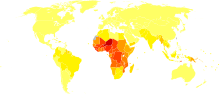

♦ Occurrence of chloroquine-resistant malaria

♦ No Plasmodium falciparum or chloroquine-resistance

♦ No malaria

The WHO estimates that in 2010 there were 219 million cases of malaria resulting in 660,000 deaths.[80][3] Others have estimated the number of cases at between 350 and 550 million for falciparum malaria[81] and deaths in 2010 at 1.24 million[82] up from 1.0 million deaths in 1990.[83] The majority of cases (65%) occur in children under 15 years old.[82] About 125 million pregnant women are at risk of infection each year; in Sub-Saharan Africa, maternal malaria is associated with up to 200,000 estimated infant deaths yearly.[10] There are about 10,000 malaria cases per year in Western Europe, and 1300–1500 in the United States.[7] About 900 people died from the disease in Europe between 1993 and 2003.[43] Both the global incidence of disease and resulting mortality have declined in recent years. According to the WHO, deaths attributable to malaria in 2010 were reduced by over a third from a 2000 estimate of 985,000, largely due to the widespread use of insecticide-treated nets and artemisinin-based combination therapies.[51]

Malaria is presently endemic in a broad band around the equator, in areas of the Americas, many parts of Asia, and much of Africa; in Sub-Saharan Africa, 85–90% of malaria fatalities occur.[84] An estimate for 2009 reported that countries with the highest death rate per 100,000 of population were Ivory Coast (86.15), Angola (56.93) and Burkina Faso (50.66).[85] A 2010 estimate indicated the deadliest countries per population were Burkina Faso, Mozambique and Mali.[82] The Malaria Atlas Project aims to map global endemic levels of malaria, providing a means with which to determine the global spatial limits of the disease and to assess disease burden.[86][87] This effort led to the publication of a map of P. falciparum endemicity in 2010.[88] As of 2010, about 100 countries have endemic malaria.[80][89] Every year, 125 million international travellers visit these countries, and more than 30,000 contract the disease.[43]

The geographic distribution of malaria within large regions is complex, and malaria-afflicted and malaria-free areas are often found close to each other.[90] Malaria is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions because of rainfall, consistent high temperatures and high humidity, along with stagnant waters in which mosquito larvae readily mature, providing them with the environment they need for continuous breeding.[91] In drier areas, outbreaks of malaria have been predicted with reasonable accuracy by mapping rainfall.[92] Malaria is more common in rural areas than in cities. For example, several cities in the Greater Mekong Subregion of Southeast Asia are essentially malaria-free, but the disease is prevalent in many rural regions, including along international borders and forest fringes.[93] In contrast, malaria in Africa is present in both rural and urban areas, though the risk is lower in the larger cities.[94]

History

Although the parasite responsible for P. falciparum malaria has been in existence for 50,000–100,000 years, the population size of the parasite did not increase until about 10,000 years ago, concurrently with advances in agriculture[95] and the development of human settlements. Close relatives of the human malaria parasites remain common in chimpanzees. Some evidence suggests that the P. falciparum malaria may have originated in gorillas.[96]

References to the unique periodic fevers of malaria are found throughout recorded history, beginning in 2700 BC in China.[97] Malaria may have contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire,[98] and was so pervasive in Rome that it was known as the "Roman fever".[99] Several regions in ancient Rome were considered at-risk for the disease because of the favourable conditions present for malaria vectors. This included areas such as southern Italy, the island of Sardinia, the Pontine Marshes, the lower regions of coastal Etruria and the city of Rome along the Tiber River. The presence of stagnant water in these places was preferred by mosquitoes for breeding grounds. Irrigated gardens, swamp-like grounds, runoff from agriculture, and drainage problems from road construction led to the increase of standing water.[100]

The term malaria originates from Medieval Italian: mala aria — "bad air"; the disease was formerly called ague or marsh fever due to its association with swamps and marshland.[101] Malaria was once common in most of Europe and North America,[102] where it is no longer endemic,[103] though imported cases do occur.[104]

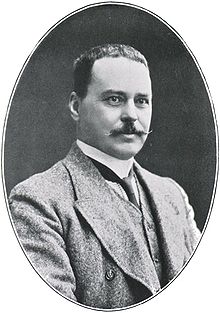

Malaria was the most important health hazard encountered by U.S. troops in the South Pacific during World War II, where about 500,000 men were infected.[105] According to Joseph Patrick Byrne, "Sixty thousand American soldiers died of malaria during the African and South Pacific campaigns."[106] Scientific studies on malaria made their first significant advance in 1880, when Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran—a French army doctor working in the military hospital of Constantine in Algeria—observed parasites inside the red blood cells of infected people for the first time. He therefore proposed that malaria is caused by this organism, the first time a protist was identified as causing disease.[107] For this and later discoveries, he was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. A year later, Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor treating people with yellow fever in Havana, provided strong evidence that mosquitoes were transmitting disease to and from humans.[108] This work followed earlier suggestions by Josiah C. Nott,[109] and work by Sir Patrick Manson, the "father of tropical medicine", on the transmission of filariasis.[110]

In April 1894, a Scottish physician Sir Ronald Ross visited Sir Patrick Manson at his house on Queen Anne Street, London. This visit was the start of four years of collaboration and fervent research that culminated in 1898 when Ross, who was working in the Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta, proved the complete life-cycle of the malaria parasite in mosquitoes. He thus proved that the mosquito was the vector for malaria in humans by showing that certain mosquito species transmit malaria to birds. He isolated malaria parasites from the salivary glands of mosquitoes that had fed on infected birds.[111] For this work, Ross received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Medicine. After resigning from the Indian Medical Service, Ross worked at the newly established Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and directed malaria-control efforts in Egypt, Panama, Greece and Mauritius.[112] The findings of Finlay and Ross were later confirmed by a medical board headed by Walter Reed in 1900. Its recommendations were implemented by William C. Gorgas in the health measures undertaken during construction of the Panama Canal. This public-health work saved the lives of thousands of workers and helped develop the methods used in future public-health campaigns against the disease.[113]

The first effective treatment for malaria came from the bark of cinchona tree, which contains quinine. This tree grows on the slopes of the Andes, mainly in Peru. The indigenous peoples of Peru made a tincture of cinchona to control fever. Its effectiveness against malaria was found and the Jesuits introduced the treatment to Europe around 1640; by 1677, it was included in the London Pharmacopoeia as an antimalarial treatment.[114] It was not until 1820 that the active ingredient, quinine, was extracted from the bark, isolated and named by the French chemists Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou.[115][116]

Quinine become the predominant malarial medication until the 1920s, when other medications began to be developed. In the 1940s, chloroquine replaced quinine as the treatment of both uncomplicated and severe malaria until resistance supervened, first in Southeast Asia and South America in the 1950s and then globally in the 1980s.[117] Artemisinins, discovered by Chinese scientist Tu Youyou and colleagues in the 1970s from the plant Artemisia annua, became the recommended treatment for P. falciparum malaria, administered in combination with other antimalarials as well as in severe disease.[118]

Plasmodium vivax was used between 1917 and the 1940s for malariotherapy—deliberate injection of malaria parasites to induce fever to combat certain diseases such as tertiary syphilis. In 1917, the inventor of this technique, Julius Wagner-Jauregg, received the Noble Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discoveries. The technique was dangerous, killing about 15% of patients, so it is no longer in use.[119]

The first pesticide used for indoor residual spraying was DDT.[120] Although it was initially used exclusively to combat malaria, its use quickly spread to agriculture. In time, pest control, rather than disease control, came to dominate DDT use, and this large-scale agricultural use led to the evolution of resistant mosquitoes in many regions. The DDT resistance shown by Anopheles mosquitoes can be compared to antibiotic resistance shown by bacteria. During the 1960s, awareness of the negative consequences of its indiscriminate use increased, ultimately leading to bans on agricultural applications of DDT in many countries in the 1970s.[48] Before DDT, malaria was successfully eliminated or controlled in tropical areas like Brazil and Egypt by removing or poisoning the breeding grounds of the mosquitoes or the aquatic habitats of the larva stages, for example by applying the highly toxic arsenic compound Paris Green to places with standing water.[121]

Malaria vaccines have been an elusive goal of research. The first promising studies demonstrating the potential for a malaria vaccine were performed in 1967 by immunizing mice with live, radiation-attenuated sporozoites, which provided significant protection to the mice upon subsequent injection with normal, viable sporozoites. Since the 1970s, there has been a considerable effort to develop similar vaccination strategies within humans.[122]

Society and culture

Economic impact

Malaria is not just a disease commonly associated with poverty: some evidence suggests that it is also a cause of poverty and a major hindrance to economic development.[123][124] Although tropical regions are most affected, malaria's furthest influence reaches into some temperate zones that have extreme seasonal changes. The disease has been associated with major negative economic effects on regions where it is widespread. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a major factor in the slow economic development of the American southern states.[125]

A comparison of average per capita GDP in 1995, adjusted for parity of purchasing power, between countries with malaria and countries without malaria gives a fivefold difference ($1,526 USD versus $8,268 USD). In the period 1965 to 1990, countries where malaria was common had an average per capita GDP that increased only 0.4% per year, compared to 2.4% per year in other countries.[126]

Poverty can increase the risk of malaria, since those in poverty do not have the financial capacities to prevent or treat the disease. In its entirety, the economic impact of malaria has been estimated to cost Africa $12 billion USD every year. The economic impact includes costs of health care, working days lost due to sickness, days lost in education, decreased productivity due to brain damage from cerebral malaria, and loss of investment and tourism.[127] The disease has a heavy burden in some countries, where it may be responsible for 30–50% of hospital admissions, up to 50% of outpatient visits, and up to 40% of public health spending.[128]

Cerebral malaria is one of the leading causes of neurological disabilities in African children.[78] Studies comparing cognitive functions before and after treatment for severe malarial illness continued to show significantly impaired school performance and cognitive abilities even after recovery.[76] Consequently, severe and cerebral malaria have far-reaching socioeconomic consequences that extend beyond the immediate effects of the disease.[129]

Counterfeit and substandard drugs

Sophisticated counterfeits have been found in several Asian countries such as Cambodia,[130] China,[131] Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, and are an important cause of avoidable death in those countries.[132] The WHO said that studies indicate that up to 40% of artesunate-based malaria medications are counterfeit, especially in the Greater Mekong region and have established a rapid alert system to enable information about counterfeit drugs to be rapidly reported to the relevant authorities in participating countries.[133] There is no reliable way for doctors or lay people to detect counterfeit drugs without help from a laboratory. Companies are attempting to combat the persistence of counterfeit drugs by using new technology to provide security from source to distribution.[134]

Another clinical and public health concern is the proliferation of substandard antimalarial medicines resulting from inappropriate concentration of ingredients, contamination with other drugs or toxic impurities, poor quality ingredients, poor stability and inadequate packaging.[135] A 2012 study demonstrated that roughly one-third of antimalarial medications in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa failed chemical analysis, packaging analysis, or were falsified.[1]

War

Throughout history, the contraction of malaria has played a prominent role in the fates of government rulers, nation-states, military personnel, and military actions.[136] In 1910, Nobel Prize in Medicine-winner Ronald Ross (himself a malaria survivor), published a book titled The Prevention of Malaria that included a chapter titled "The Prevention of Malaria in War." The chapter's author, Colonel C. H. Melville, Professor of Hygiene at Royal Army Medical College in London, addressed the prominent role that malaria has historically played during wars: "The history of malaria in war might almost be taken to be the history of war itself, certainly the history of war in the Christian era. ... It is probably the case that many of the so-called camp fevers, and probably also a considerable proportion of the camp dysentery, of the wars of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were malarial in origin."[137]

Significant financial investments have been made to procure existing and create new anti-malarial agents. During World War I and World War II, inconsistent supplies of the natural anti-malaria drugs cinchona bark and quinine prompted substantial funding into research and development of other drugs and vaccines. American military organizations conducting such research initiatives include the Navy Medical Research Center, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases of the US Armed Forces.[138]

Additionally, initiatives have been founded such as Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA), established in 1942, and its successor, the Communicable Disease Center (now known as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC) established in 1946. According to the CDC, MCWA "was established to control malaria around military training bases in the southern United States and its territories, where malaria was still problematic".[139]

Eradication efforts

Several notable attempts are being made to eliminate the parasite from sections of the world, or to eradicate it worldwide. In 2006, the organization Malaria No More set a public goal of eliminating malaria from Africa by 2015, and the organization plans to dissolve if that goal is accomplished.[140] Several malaria vaccines are in clinical trials, which are intended to provide protection for children in endemic areas and reduce the speed of transmission of the disease. As of 2012[update], The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria has distributed 230 million insecticide-treated nets intended to stop mosquito-borne transmission of malaria.[141] The U.S.-based Clinton Foundation has worked to manage demand and stabilize prices in the artemisinin market.[142] Other efforts, such as the Malaria Atlas Project, focus on analysing climate and weather information required to accurately predict the spread of malaria based on the availability of habitat of malaria-carrying parasites.[86]

Malaria has been successfully eliminated or greatly reduced in certain areas. Malaria was once common in the United States and southern Europe, but vector control programs, in conjunction with the monitoring and treatment of infected humans, eliminated it from those regions. Several factors contributed, such as the draining of wetland breeding grounds for agriculture and other changes in water management practices, and advances in sanitation, including greater use of glass windows and screens in dwellings.[143] Malaria was eliminated from most parts of the USA in the early 20th century by such methods, and the use of the pesticide DDT and other means eliminated it from the remaining pockets in the South in the 1950s.[144] (see National Malaria Eradication Program) In Suriname, the disease has been cleared from its capital city and coastal areas through a three-pronged approach initiated by the Global Malaria Eradication program in 1955, involving: vector control through the use of DDT and IRS; regular collection of blood smears from the population to identify existing malaria cases; and providing chemotherapy to all affected individuals.[145] Bhutan is pursuing an aggressive malaria elimination strategy, and has achieved a 98.7% decline in microscopy-confirmed cases from 1994 to 2010. In addition to vector control techniques such as IRS in high-risk areas and thorough distribution of long-lasting ITNs, factors such as economic development and increasing access to health services have contributed to Bhutan's successes in reducing malaria incidence.[146]

Research

Immunity (or, more accurately, tolerance) to P. falciparum malaria does occur naturally, but only in response to years of repeated infection.[147] An individual can be protected from a P. falciparum infection if they receive about a thousand bites from mosquitoes that carry a version of the parasite rendered non-infective by a dose of X-ray irradiation.[148] An effective vaccine is not yet available for malaria, although several are under development.[149] The highly polymorphic nature of many P. falciparum proteins results in significant challenges to vaccine design. Vaccine candidates that target antigens on gametes, zygotes, or ookinetes in the mosquito midgut aim to block the transmission of malaria. These transmission-blocking vaccines induce antibodies in the human blood; when a mosquito takes a blood meal from a protected individual, these antibodies prevent the parasite from completing its development in the mosquito.[150] Other vaccine candidates, targeting the blood-stage of the parasite's life cycle, have been inadequate on their own.[151] For example, SPf66 was tested extensively in endemic areas in the 1990s, but clinical trials showed it to be insufficiently effective.[152] Several potential vaccines targeting the pre-erythrocytic stage of the parasite's life cycle are being developed, with RTS,S as the leading candidate;[148] it is expected to be licensed in 2015.[77] A US biotech company, Sanaria, is developing a pre-erythrocytic attenuated vaccine called PfSPZ that uses whole sporozoites to induce an immune response.[153] In 2006, the Malaria Vaccine Advisory Committee to the WHO outlined a "Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap" that has as one of its landmark objectives to "develop and license a first-generation malaria vaccine that has a protective efficacy of more than 50% against severe disease and death and lasts longer than one year" by 2015.[154]

Malaria parasites contain apicoplasts, organelles usually found in plants, complete with their own genomes. These apicoplasts are thought to have originated through the endosymbiosis of algae and play a crucial role in various aspects of parasite metabolism, such as fatty acid biosynthesis. Over 400 proteins have been found to be produced by apicoplasts and these are now being investigated as possible targets for novel anti-malarial drugs.[155]

With the onset of drug-resistant Plasmodium parasites, new strategies are being developed to combat the widespread disease. One such approach lies in the introduction of synthetic pyridoxal-amino acid adducts, which are taken up by the parasite and ultimately interfere with its ability to create several essential B vitamins.[156][157] Antimalarial drugs using synthetic metal-based complexes are attracting research interest.[158][159]

A non-chemical vector control strategy involves genetic manipulation of malaria mosquitoes. Advances in genetic engineering technologies make it possible to introduce foreign DNA into the mosquito genome and either decrease the lifespan of the mosquito, or make it more resistant to the malaria parasite. Sterile insect technique is a genetic control method whereby large numbers of sterile males mosquitoes are reared and released. Mating with wild females reduces the wild population in the subsequent generation; repeated releases eventually eliminate the target population.[50]

Other animals

Nearly 200 parasitic Plasmodium species have been identified that infect birds, reptiles, and other mammals,[160] and about 30 species naturally infect non-human primates.[161] Some of the malaria parasites that affect non-human primates (NHP) serve as model organisms for human malarial parasites, such as P. coatneyi (a model for P. falciparum) and P. cynomolgi (P. vivax). Diagnostic techniques used to detect parasites in NHP are similar to those employed for humans.[162] Malaria parasites that infect rodents are widely used as models in research, such as P. berghei.[163] Avian malaria primarily affects species of the order Passeriformes, and poses a substantial threat to birds of Hawaii, the Galapagos, and other archipelagoes. The parasite P. relictum is known to play a role in limiting the distribution and abundance of endemic Hawaiian birds. Global warming is expected to increase the prevalence and global distribution of avian malaria, as elevated temperatures provide optimal conditions for parasite reproduction.[164]

References

- ^ a b Nayyar GML, Breman JG, Newton PN, Herrington J (2012). "Poor-quality antimalarial drugs in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa". Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (6): 488–96. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70064-6. PMID 22632187.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fairhurst RM, Wellems TE (2010). "Chapter 275. Plasmodium species (malaria)". In Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R (eds) (ed.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol. 2 (7th ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 3437–3462. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

{{cite book}}:|editor-last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Nadjm B, Behrens RH (2012). "Malaria: An update for physicians". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 26 (2): 243–59. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.010. PMID 22632637.

- ^ a b c d e Bartoloni A, Zammarchi L (2012). "Clinical aspects of uncomplicated and severe malaria". Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 4 (1): e2012026. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2012.026. PMC 3375727. PMID 22708041.

- ^ Beare NA, Taylor TE, Harding SP, Lewallen S, Molyneux ME (2006). "Malarial retinopathy: A newly established diagnostic sign in severe malaria". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 75 (5): 790–7. PMC 2367432. PMID 17123967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Ferri FF (2009). "Chapter 332. Protozoal infections". Ferri's Color Atlas and Text of Clinical Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1159. ISBN 978-1-4160-4919-7.

- ^ a b Taylor WR, Hanson J, Turner GD, White NJ, Dondorp AM (2012). "Respiratory manifestations of malaria". Chest. 142 (2): 492–505. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2655. PMID 22871759.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Korenromp E, Williams B, de Vlas S, Gouws E, Gilks C, Ghys P, Nahlen B (2005). "Malaria attributable to the HIV-1 epidemic, sub-Saharan Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (9): 1410–9. doi:10.3201/eid1109.050337. PMC 3310631. PMID 16229771.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Beare NA, Lewallen S, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME (2011). "Redefining cerebral malaria by including malaria retinopathy". Future Microbiology. 6 (3): 349–55. doi:10.2217/fmb.11.3. PMC 3139111. PMID 21449844.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b Hartman TK, Rogerson SJ, Fischer PR (2010). "The impact of maternal malaria on newborns". Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 30 (4): 271–82. doi:10.1179/146532810X12858955921032. PMID 21118620.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rijken MJ, McGready R, Boel ME, Poespoprodjo R, Singh N, Syafruddin D, Rogerson S, Nosten F (2012). "Malaria in pregnancy in the Asia-Pacific region". Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 75–88. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70315-2. PMID 22192132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mueller I, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC (2007). "Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale—the "bashful" malaria parasites". Trends in Parasitology. 23 (6): 278–83. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2007.04.009. PMC 3728836. PMID 17459775.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Collins WE (2012). "Plasmodium knowlesi: A malaria parasite of monkeys and humans". Annual Review of Entomology. 57: 107–21. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-121510-133540. PMID 22149265.

- ^ a b Sarkar PK, Ahluwalia G, Vijayan VK, Talwar A (2009). "Critical care aspects of malaria". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 25 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1177/0885066609356052. PMID 20018606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baird JK (2013). "Evidence and implications of mortality associated with acute Plasmodium vivax malaria". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (1): 36–57. doi:10.1128/CMR.00074-12. PMC 3553673. PMID 23297258.

- ^ Arnott A, Barry AE, Reeder JC (2012). "Understanding the population genetics of Plasmodium vivax is essential for malaria control and elimination". Malaria Journal. 11: 14. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-14. PMC 3298510. PMID 22233585.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Collins WE, Barnwell JW (2009). "Plasmodium knowlesi: finally being recognized". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 199 (8): 1107–8. doi:10.1086/597415. PMID 19284287.

- ^ Schlagenhauf-Lawlor 2008, pp. 70–1

- ^ Cowman AF, Berry D, Baum J (2012). "The cellular and molecular basis for malaria parasite invasion of the human red blood cell". Journal of Cell Biology. 198 (6): 961–71. doi:10.1083/jcb.201206112. PMC 3444787. PMID 22986493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Arrow KJ, Panosian C, Gelband H, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on the Economics of Antimalarial Drugs (2004). Saving Lives, Buying Time: Economics of Malaria Drugs in an Age of Resistance. National Academies Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-309-09218-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Owusu-Ofori AK, Parry C, Bates I (2010). "Transfusion-transmitted malaria in countries where malaria is endemic: A review of the literature from sub-Saharan Africa". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 51 (10): 1192–8. doi:10.1086/656806. PMID 20929356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ WHO 2010, p. vi

- ^ a b White NJ (2011). "Determinants of relapse periodicity in Plasmodium vivax malaria". Malaria Journal. 10: 297. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-297. PMC 3228849. PMID 21989376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ WHO 2010, p. 17

- ^ a b c Bledsoe GH (2005). "Malaria primer for clinicians in the United States". Southern Medical Journal. 98 (12): 1197–204, quiz 1205, 1230. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000189904.50838.eb. PMID 16440920.

- ^ Vaughan AM, Aly AS, Kappe SH (2008). "Malaria parasite pre-erythrocytic stage infection: Gliding and hiding". Cell Host & Microbe. 4 (3): 209–18. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.010. PMC 2610487. PMID 18779047.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Richter J, Franken G, Mehlhorn H, Labisch A, Häussinger D (2010). "What is the evidence for the existence of Plasmodium ovale hypnozoites?". Parasitology Research. 107 (6): 1285–90. doi:10.1007/s00436-010-2071-z. PMID 20922429.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tilley L, Dixon MW, Kirk K (2011). "The Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cell". International Journal of Biochemicstry and Cell Biology. 43 (6): 839–42. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2011.03.012. PMID 21458590.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mens PF, Bojtor EC, Schallig HDFH (2012). "Molecular interactions in the placenta during malaria infection". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 152 (2): 126–32. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.05.013. PMID 20933151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rénia L, Wu Howland S, Claser C, Charlotte Gruner A, Suwanarusk R, Hui Teo T, Russell B, Ng LF (2012). "Cerebral malaria: mysteries at the blood-brain barrier". Virulence. 3 (2): 193–201. doi:10.4161/viru.19013. PMC 3396698. PMID 22460644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Kwiatkowski DP (2005). "How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria". American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (2): 171–92. doi:10.1086/432519. PMC 1224522. PMID 16001361.

- ^ a b Hedrick PW (2011). "Population genetics of malaria resistance in humans". Heredity. 107 (4): 283–304. doi:10.1038/hdy.2011.16. PMC 3182497. PMID 21427751.

- ^ Weatherall DJ (2008). "Genetic variation and susceptibility to infection: The red cell and malaria". British Journal of Haematology. 141 (3): 276–86. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07085.x. PMID 18410566.

- ^ a b Bhalla A, Suri V, Singh V (2006). "Malarial hepatopathy". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 52 (4): 315–20. PMID 17102560.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Abba K, Deeks JJ, Olliaro P, Naing CM, Jackson SM, Takwoingi Y, Donegan S, Garner P (2011). Abba, Katharine (ed.). "Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in endemic countries". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008122. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008122.pub2. PMID 21735422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kattenberg JH, Ochodo EA, Boer KR, Schallig HD, Mens PF, Leeflang MM (2011). "Systematic review and meta-analysis: Rapid diagnostic tests versus placental histology, microscopy and PCR for malaria in pregnant women". Malaria Journal. 10: 321. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-321. PMC 3228868. PMID 22035448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ a b Wilson ML (2012). "Malaria rapid diagnostic tests". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 54 (11): 1637–41. doi:10.1093/cid/cis228. PMID 22550113.

- ^ Perkins MD, Bell DR (2008). "Working without a blindfold: The critical role of diagnostics in malaria control". Malaria Journal. 1 (Suppl 1): S5. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-7-S1-S5. PMC 2604880. PMID 19091039.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ WHO 2010, p. 35

- ^ WHO 2010, p. v

- ^ World Health Organization (1958). "Malaria". The First Ten Years of the World Health Organization (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 172–87.

- ^ Sabot O, Cohen JM, Hsiang MS, Kahn JG, Basu S, Tang L, Zheng B, Gao Q, Zou L, Tatarsky A, Aboobakar S, Usas J, Barrett S, Cohen JL, Jamison DT, Feachem RG (2010). "Costs and financial feasibility of malaria elimination". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1604–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61355-4. PMC 3044845. PMID 21035839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Kajfasz P (2009). "Malaria prevention". International Maritime Health. 60 (1–2): 67–70. PMID 20205131.

- ^ Lengeler C (2004). Lengeler, Christian (ed.). "Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000363. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000363.pub2. PMID 15106149.

- ^ Tanser FC, Lengeler C, Sharp BL (2010). Lengeler, Christian (ed.). "Indoor residual spraying for preventing malaria". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006657. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006657.pub2. PMID 20393950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Enayati A, Hemingway J (2010). "Malaria management: Past, present, and future". Annual Review of Entomology. 55: 569–91. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085423. PMID 19754246.

- ^ Indoor Residual Spraying: Use of Indoor Residual Spraying for Scaling Up Global Malaria Control and Elimination. WHO Position Statement (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization. 2006.

- ^ a b van den Berg H (2009). "Global status of DDT and its alternatives for use in vector control to prevent disease". Environmental Health Perspectives. 117 (11): 1656–63. doi:10.1289/ehp.0900785. PMC 2801202. PMID 20049114.

- ^ Pates H, Curtis C (2005). "Mosquito behaviour and vector control". Annual Review of Entomology. 50: 53–70. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130439. PMID 15355233.

- ^ a b Raghavendra K, Barik TK, Reddy BP, Sharma P, Dash AP (2011). "Malaria vector control: From past to future". Parasitology Research. 108 (4): 757–79. doi:10.1007/s00436-010-2232-0. PMID 21229263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c Howitt P, Darzi A, Yang GZ, Ashrafian H, Atun R, Barlow J, Blakemore A, Bull AM, Car J, Conteh L, Cooke GS, Ford N, Gregson SA, Kerr K, King D, Kulendran M, Malkin RA, Majeed A, Matlin S, Merrifield R, Penfold HA, Reid SD, Smith PC, Stevens MM, Templeton MR, Vincent C, Wilson E (2012). "Technologies for global health". The Lancet. 380 (9840): 507–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61127-1. PMID 22857974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller JM, Korenromp EL, Nahlen BL, W Steketee R (2007). "Estimating the number of insecticide-treated nets required by African households to reach continent-wide malaria coverage targets". Journal of the American Medical Association. 297 (20): 2241–50. doi:10.1001/jama.297.20.2241. PMID 17519414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Schlagenhauf-Lawlor 2008, pp. 215

- ^ Tusting, LS (2013 Aug 29). "Mosquito larval source management for controlling malaria". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 8: CD008923. PMID 23986463.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Enayati AA, Hemingway J, Garner P. (2007). Enayati, Ahmadali (ed.). "Electronic mosquito repellents for preventing mosquito bites and malaria infection" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005434. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005434.pub2. PMID 17443590.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lalloo DG, Olukoya P, Olliaro P (2006). "Malaria in adolescence: Burden of disease, consequences, and opportunities for intervention". Lancet Infectious Diseases. 6 (12): 780–93. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70655-7. PMID 17123898.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mehlhorn H, ed. (2008). "Disease Control, Methods". Encyclopedia of Parasitology (3rd ed.). Springer. pp. 362–6. ISBN 978-3-540-48997-9.

- ^ Bardají A, Bassat Q, Alonso PL, Menéndez C (2012). "Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnant women and infants: making best use of the available evidence". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (12): 1719–36. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.703651. PMID 22775553.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meremikwu MM, Donegan S, Sinclair D, Esu E, Oringanje C (2012). Meremikwu, Martin M (ed.). "Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in children living in areas with seasonal transmission". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD003756. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003756.pub4. PMID 22336792.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c Jacquerioz FA, Croft AM (2009). Jacquerioz FA (ed.). "Drugs for preventing malaria in travellers". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006491. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006491.pub2. PMID 19821371.

- ^ Freedman DO (2008). "Clinical practice. Malaria prevention in short-term travelers". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (6): 603–12. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0803572. PMID 18687641.

- ^ Fernando SD, Rodrigo C, Rajapaske S (2011). "Chemoprophylaxis in malaria: Drugs, evidence of efficacy and costs". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 4 (4): 330–36. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60098-9. PMID 21771482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Turschner S, Efferth T (2009). "Drug resistance in Plasmodium: Natural products in the fight against malaria". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (2): 206–14. doi:10.2174/138955709787316074. PMID 19200025.

- ^ Meremikwu MM, Odigwe CC, Akudo Nwagbara B, Udoh EE (2012). Meremikwu, Martin M (ed.). "Antipyretic measures for treating fever in malaria". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD002151. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002151.pub2. PMID 22972057.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kokwaro G (2009). "Ongoing challenges in the management of malaria". Malaria Journal. 8 (Suppl 1): S2. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-8-S1-S2. PMC 2760237. PMID 19818169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ WHO 2010, pp. 75–86

- ^ WHO 2010, p. 21

- ^ Keating GM (2012). "Dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine: A review of its use in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria". Drugs. 72 (7): 937–61. doi:10.2165/11203910-000000000-00000. PMID 22515619.

- ^ Manyando C, Kayentao K, D'Alessandro U, Okafor HU, Juma E, Hamed K (2011). "A systematic review of the safety and efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine against uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria during pregnancy". Malaria Journal. 11: 141. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-141. PMC 3405476. PMID 22548983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ O'Brien C, Henrich PP, Passi N, Fidock DA (2011). "Recent clinical and molecular insights into emerging artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 24 (6): 570–7. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834cd3ed. PMC 3268008. PMID 22001944.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Fairhurst RM, Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Hallett R, Vennerstrom JL, Duong S, Ringwald P, Wellems TE, Plowe CV, Dondorp AM (2012). "Artemisinin-resistant malaria: research challenges, opportunities, and public health implications". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 87 (2): 231–41. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0025. PMC 3414557. PMID 22855752.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Waters NC, Edstein MD (2012). "8-Aminoquinolines: Primaquine and tafenoquine". In Staines HM, Krishna S (eds) (ed.). Treatment and Prevention of Malaria: Antimalarial Drug Chemistry, Action and Use. Springer. pp. 69–93. ISBN 978-3-0346-0479-6.

{{cite book}}:|editor-last=has generic name (help) - ^ Sinclair D, Donegan S, Isba R, Lalloo DG (2012). Sinclair, David (ed.). "Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD005967. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005967.pub4. PMID 22696354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): If I get malaria, will I have it for the rest of my life?". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 8, 2010. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ^ Trampuz A, Jereb M, Muzlovic I, Prabhu R (2003). "Clinical review: Severe malaria". Critical Care. 7 (4): 315–23. doi:10.1186/cc2183. PMC 270697. PMID 12930555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ a b c d Fernando SD, Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S (2010). "The 'hidden' burden of malaria: Cognitive impairment following infection". Malaria Journal. 9: 366. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-9-366. PMC 3018393. PMID 21171998.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ a b Riley EM, Stewart VA (2013). "Immune mechanisms in malaria: New insights in vaccine development". Nature Medicine. 19 (2): 168–78. doi:10.1038/nm.3083. PMID 23389617.

- ^ a b Idro R, Marsh K, John CC, Newton CRJ (2010). "Cerebral malaria: Mechanisms of brain injury and strategies for improved neuro-cognitive outcome". Pediatric Research. 68 (4): 267–74. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181eee738. PMC 3056312. PMID 20606600.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Malaria". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 15, 2010. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ a b World Malaria Report 2012 (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization.

- ^ Olupot-Olupot P, Maitland, K (2013). "Management of severe malaria: Results from recent trials". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 764: 241–50. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4726-9_20. ISBN 978-1-4614-4725-2. PMID 23654072.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD (2012). "Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis". Lancet. 379 (9814): 413–31. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8. PMID 22305225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lozano R; et al. (2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Layne SP. "Principles of Infectious Disease Epidemiology" (PDF). EPI 220. UCLA Department of Epidemiology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-20. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Provost C (April 25, 2011). "World Malaria Day: Which countries are the hardest hit? Get the full data". The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ a b Guerra CA, Hay SI, Lucioparedes LS, Gikandi PW, Tatem AJ, Noor AM, Snow RW (2007). "Assembling a global database of malaria parasite prevalence for the Malaria Atlas Project". Malaria Journal. 6 (6): 17. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-6-17. PMC 1805762. PMID 17306022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Hay SI, Okiro EA, Gething PW, Patil AP, Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Snow RW (2010). Mueller, Ivo (ed.). "Estimating the global clinical burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 2007". PLoS Medicine. 7 (6): e1000290. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000290. PMC 2885984. PMID 20563310.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Gething PW, Patil AP, Smith DL, Guerra CA, Elyazar IR, Johnston GL, Tatem AJ, Hay SI (2011). "A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010". Malaria Journal. 10 (1): 378. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-378. PMC 3274487. PMID 22185615.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Feachem RG, Phillips AA, Hwang J, Cotter C, Wielgosz B, Greenwood BM, Sabot O, Rodriguez MH, Abeyasinghe RR, Ghebreyesus TA, Snow RW (2010). "Shrinking the malaria map: progress and prospects". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1566–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61270-6. PMC 3044848. PMID 21035842.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Greenwood B, Mutabingwa T (2002). "Malaria in 2002". Nature. 415 (6872): 670–2. doi:10.1038/415670a. PMID 11832954.

- ^ Jamieson A, Toovey S, Maurel M (2006). Malaria: A Traveller's Guide. Struik. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-77007-353-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abeku TA (2007). "Response to malaria epidemics in Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (5): 681–6. doi:10.3201/eid1305.061333. PMC 2738452. PMID 17553244.

- ^ Cui L, Yan G, Sattabongkot J, Cao Y, Chen B, Chen X, Fan Q, Fang Q, Jongwutiwes S, Parker D, Sirichaisinthop J, Kyaw MP, Su XZ, Yang H, Yang Z, Wang B, Xu J, Zheng B, Zhong D, Zhou G (2012). "Malaria in the Greater Mekong Subregion: Heterogeneity and complexity". Acta Tropica. 121 (3): 227–39. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.02.016. PMC 3132579. PMID 21382335.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Machault V, Vignolles C, Borchi F, Vounatsou P, Pages F, Briolant S, Lacaux JP, Rogier C (2011). "The use of remotely sensed environmental data in the study of malaria" (PDF). Geospatial Health. 5 (2): 151–68. PMID 21590665.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harper K, Armelagos G (2011). "The changing disease-scape in the third epidemiological transition". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (2): 675–97. doi:10.3390/ijerph7020675. PMC 2872288. PMID 20616997.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Prugnolle F, Durand P, Ollomo B, Duval L, Ariey F, Arnathau C, Gonzalez JP, Leroy E, Renaud F (2011). Manchester, Marianne (ed.). "A fresh look at the origin of Plasmodium falciparum, the most malignant malaria agent". PLoS Pathogens. 7 (2): e1001283. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001283. PMC 3044689. PMID 21383971.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Cox F (2002). "History of human parasitology". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 15 (4): 595–612. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.4.595-612.2002. PMC 126866. PMID 12364371.

- ^ "DNA clues to malaria in ancient Rome". BBC News. February 20, 2001., in reference to Sallares R, Gomzi S (2001). "Biomolecular archaeology of malaria". Ancient Biomolecules. 3 (3): 195–213. OCLC 538284457.

- ^ Sallares R (2002). Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199248506.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-924850-6.

- ^ Hays JN (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-85109-658-9.

- ^ Reiter P (2000). "From Shakespeare to Defoe: Malaria in England in the Little Ice Age". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.3201/eid0601.000101. PMC 2627969. PMID 10653562.

- ^ Lindemann M (1999). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-42354-0.

- ^ Gratz NG, World Health Organization (2006). The Vector- and Rodent-borne Diseases of Europe and North America: Their Distribution and Public Health Burden. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-521-85447-4.

- ^ Webb Jr JLA (2009). Humanity's Burden: A Global History of Malaria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67012-8.

- ^ Bray RS (2004). Armies of Pestilence: The Effects of Pandemics on History. James Clarke. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-227-17240-7.

- ^ Byrne JP (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1907: Alphonse Laveran". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ^ Tan SY, Sung H (2008). "Carlos Juan Finlay (1833–1915): Of mosquitoes and yellow fever" (PDF). Singapore Medical Journal. 49 (5): 370–1. PMID 18465043.

- ^ Chernin E (1983). "Josiah Clark Nott, insects, and yellow fever". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 59 (9): 790–802. PMC 1911699. PMID 6140039.

- ^ Chernin E (1977). "Patrick Manson (1844–1922) and the transmission of filariasis". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 26 (5 Pt 2 Suppl): 1065–70. PMID 20786.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1902: Ronald Ross". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ^ "Ross and the Discovery that Mosquitoes Transmit Malaria Parasites". CDC Malaria website. Archived from the original on 2007-06-02. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ Simmons JS (1979). Malaria in Panama. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-10628-6.