Marshalltown, Iowa

Marshalltown, Iowa | |

|---|---|

| City of Marshalltown | |

Main Street Marshalltown (2011) | |

Location within Marshall County and Iowa | |

| Coordinates: 42°2′30″N 92°54′52″W / 42.04167°N 92.91444°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Marshall |

| Founded | 1853 |

| Incorporated | March 5, 1923[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joel Greer[2] |

| • City Administrator | Jessica Kinser |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19.22 sq mi (49.79 km2) |

| • Land | 19.20 sq mi (49.72 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km2) |

| Elevation | 942 ft (287 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 27,591 |

| • Rank | 17th in Iowa |

| • Density | 1,437.18/sq mi (554.89/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 50158 |

| Area code | 641 |

| FIPS code | 19-49755 |

| GNIS ID | 0458824 |

| Website | www |

Marshalltown is a city in and the county seat of Marshall County, Iowa, United States, located along the Iowa River.[4] It is the seat and most populous settlement of Marshall County and the 16th largest city in Iowa, with a population of 27,591 at the 2020 census.[5] Marshalltown is home to the Iowa Veterans Home and Marshalltown Community College.

History

Henry Anson was the first European settler in what is now called Marshalltown. In April 1851, Anson found what he described as “the prettiest place in Iowa.”[6] On a high point between the Iowa River and Linn Creek, Anson built a log cabin. A plaque at 112 West Main Street marks the site of the cabin.[7] In 1853 Anson named the town Marshall, after Marshall, Michigan, a former residence of his.[8]

The town became Marshalltown in 1862 because another Marshall already existed in Henry County, Iowa (In 1880, Marshall's name changed to Wayland). With the help of Potawatomi chief Johnny Green, Anson persuaded early settlers to stay in the area. In the mid-1850s, Anson donated land for a county courthouse. Residents donated money for the building's construction. In 1863 the title of county seat transferred from the village of Marietta to Marshalltown. The young town then began growing. By 1900, Marshalltown had 10,000 residents. Many industries began developing in Marshalltown, like Fisher Controls, Lennox International and Marshalltown Company.

Marshalltown plays a small but significant role in the life of Ebe Dolliver, a main character in MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel "Andersonville" (1955).

Baseball

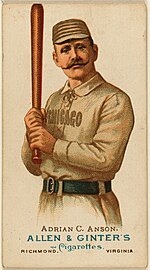

Adrian Constantine "Cap" Anson, son of Henry and Jennette Anson, was the first European child born in the new pioneer town and is today known as Marshalltown's “first son.” Adrian became a Major League Baseball player and was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939. He was regarded as one of the greatest players of his era and one of the first superstars of the game.[9]

Baseball steadily became popular as Marshalltown grew in the mid-1800s. Adrian's brother Sturgis also became a talented baseball player and both went to play on intra-school teams at the University of Notre Dame. Both later returned to Marshalltown to play baseball for the town team. Along with their father Henry, the town's founder, they put together a team and became the most prominent team in the state of Iowa.[10] The Marshalltown team, with Henry Anson at third base, Adrian's brother Sturgis in center field, and Adrian at second base, won the Iowa state championship in 1868. In 1870 Marshalltown played an exhibition game with the talented Rockford Forest Citys. Although Marshalltown lost the game, Rockford's management offered contracts to all three of the Ansons. Adrian accepted the contract, which began his professional career in baseball in 1871.

Baseball continued its popularity in Marshalltown. In the early 1880s Billy Sunday played for the town baseball team.[11] In 1882, with Sunday in left field, the Marshalltown team defeated the state champion Des Moines team 13–4.[12] Marshalltown later formed a minor league team naming it after the Anson family, the Marshalltown Ansons. From 1914 to 1928 the team played in the Central Association and Mississippi Valley League.

Natural disasters

Tornado history

On April 23, 1961, the south side of town was hit by an F3 tornado. It damaged numerous structures in the area, causing $1 million (1961 USD) in the town alone. It killed one person and injured 12.[13] Marshalltown would be hit again on July 19, 2018, when another EF3 tornado with peak winds of 144 mph moved directly through downtown at 4:37 p.m. local time. It destroyed the spire from the top of the courthouse, while heavily damaging or destroying several homes, businesses, and historic downtown buildings. It was on the ground for 23 minutes along a 8.41-mile-long (13.53 km) path of destruction up to 1,200 yards (1,100 m) wide. Although there were no fatalities, 23 people were injured.[14]

2020 Derecho

On August 10, 2020, Marshalltown was hit by a powerful derecho, which caused extensive damage throughout the city. Over a hundred cars parked near a factory had their windows blown out. Reports described 99 miles per hour (160 kilometers per hour; 44 meters per second) winds, roofs being ripped off, and loose wood debris embedded in the sides of buildings.[15][16][17] One week after the storm, nearly 7,000 residents of the city were still waiting for power restoration; 99 percent restoration was achieved on August 23.[18][19] The damage to public parks in the city and surrounding Marshall County was "extensive", particularly to trees.[20]

Immigration

Marshalltown's Hispanic population in particular boomed in the 1990s and 2000s with immigrants mostly from Mexico, just like in many other Midwestern towns with meat-packing plants.[21] Another smaller wave of Burmese refugees later arrived in the 2010s.[22]

Federal law enforcement have twice raided the Swift & Company (now JBS) meatpacking plant, first in 1996 and again in 2006, arresting suspected undocumented immigrants for alleged identity theft.[23] One study estimated the 2006 raid caused a 6-month to 1-year economic recession in the area.[24] Explaining the 2006 raid's effect on the community, Police Chief Michael Tupper told The Washington Post in 2018 that “I think that there’s just a lot of fear that it could happen again. It was a very traumatic experience for our community. Not just for the families and people that were directly impacted, but for our school system, for our local economy, for our community as a whole. It was, in many ways, a devastating experience.”[25]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 19.31 square miles (50.01 km2), of which 19.28 square miles (49.93 km2) is land and 0.03 square miles (0.08 km2) is water.[26] Neighboring counties include Hardin and Grundy to the north, Tama to the east, Jasper to the south, and Story to the west.

Climate

According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Marshalltown has a hot-summer humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfa" on climate maps.

| Climate data for Marshalltown, Iowa, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

73 (23) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

112 (44) |

109 (43) |

103 (39) |

94 (34) |

81 (27) |

73 (23) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 49.2 (9.6) |

55.2 (12.9) |

70.9 (21.6) |

81.8 (27.7) |

88.2 (31.2) |

91.8 (33.2) |

93.3 (34.1) |

91.5 (33.1) |

89.4 (31.9) |

82.9 (28.3) |

68.8 (20.4) |

54.5 (12.5) |

94.6 (34.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 27.5 (−2.5) |

32.3 (0.2) |

45.4 (7.4) |

59.5 (15.3) |

70.7 (21.5) |

80.4 (26.9) |

83.5 (28.6) |

81.5 (27.5) |

75.4 (24.1) |

62.2 (16.8) |

46.5 (8.1) |

33.5 (0.8) |

58.2 (14.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 18.2 (−7.7) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

35.1 (1.7) |

47.7 (8.7) |

59.6 (15.3) |

69.8 (21.0) |

73.1 (22.8) |

70.6 (21.4) |

63.0 (17.2) |

50.4 (10.2) |

36.4 (2.4) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

47.6 (8.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 9.0 (−12.8) |

13.0 (−10.6) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

35.9 (2.2) |

48.5 (9.2) |

59.2 (15.1) |

62.7 (17.1) |

59.7 (15.4) |

50.6 (10.3) |

38.6 (3.7) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

15.6 (−9.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −14.5 (−25.8) |

−9.1 (−22.8) |

3.2 (−16.0) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

33.7 (0.9) |

46.8 (8.2) |

51.9 (11.1) |

49.3 (9.6) |

35.4 (1.9) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

9.5 (−12.5) |

−5.9 (−21.1) |

−18.2 (−27.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −34 (−37) |

−35 (−37) |

−32 (−36) |

4 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

35 (2) |

20 (−7) |

−3 (−19) |

−11 (−24) |

−28 (−33) |

−35 (−37) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.97 (25) |

1.16 (29) |

2.10 (53) |

3.82 (97) |

4.94 (125) |

5.93 (151) |

4.58 (116) |

4.37 (111) |

3.65 (93) |

2.66 (68) |

2.10 (53) |

1.39 (35) |

37.87 (962) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.3 (16) |

5.3 (13) |

3.3 (8.4) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.7 (4.3) |

7.8 (20) |

25.3 (64) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.6 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 10.8 | 12.9 | 11.7 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 105.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.1 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 15.6 |

| Source: NOAA[27][28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 981 | — | |

| 1870 | 3,218 | 228.0% | |

| 1880 | 6,240 | 93.9% | |

| 1890 | 8,914 | 42.9% | |

| 1900 | 11,544 | 29.5% | |

| 1910 | 13,374 | 15.9% | |

| 1920 | 15,731 | 17.6% | |

| 1930 | 17,373 | 10.4% | |

| 1940 | 19,240 | 10.7% | |

| 1950 | 19,821 | 3.0% | |

| 1960 | 22,521 | 13.6% | |

| 1970 | 26,219 | 16.4% | |

| 1980 | 26,938 | 2.7% | |

| 1990 | 25,178 | −6.5% | |

| 2000 | 26,009 | 3.3% | |

| 2010 | 27,552 | 5.9% | |

| 2020 | 27,591 | 0.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29][5] | |||

Marshalltown is notably more ethnically diverse than the State of Iowa overall. In 2019, 85% of Iowans were non-Hispanic whites, compared to just 59.8% of Marshalltonians.[30] Most of this discrepancy can be explained by the sizable Hispanic population in Marshalltown (30.7% in 2019).

| Racial Composition | 2019[30] | 2010[31] | 2000[31] | 1990[32] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 81.1% | 84.8% | 86.8% | 97.1% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 59.8% | 70.3% | 83.6% | 96.6% |

| Black or African American | 1.6% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 1.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 30.7% | 24.1% | 12.6% | 1.0% |

| Asian | 5.2% | 1.7% | 1.0% | 1.1% |

2010 census

At the 2010 census there were 27,552 people in 10,335 households, including 6,629 families, in the city. The population density was 1,429.0 inhabitants per square mile (551.7/km2). There were 11,171 housing units at an average density of 579.4 per square mile (223.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 84.8% White, 2.2% African American, 0.6% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 7.9% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 24.1%.[33]

Of the 10,335 households 33.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.1% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 35.9% were non-families. 29.8% of households were one person and 12.6% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.55 and the average family size was 3.18.

The median age was 37.3 years. 26.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.1% were from 25 to 44; 24.9% were from 45 to 64; and 16.7% were 65 or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.8% male and 50.2% female.

2000 census

At the 2000 census there were 26,009 people in 10,175 households, including 6,593 families, in the city. The population density was 1,442.7 inhabitants per square mile (557.0/km2). There were 10,857 housing units at an average density of 602.2 per square mile (232.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 86.8% White, 1.3% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.3% Asian, 8.6% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 12.6%.[34]

Of the 10,175 households 30.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.5% were married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.2% were non-families. 29.7% of households were one person and 13.5% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.02.

Age spread: 24.5% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 26.0% from 25 to 44, 23.0% from 45 to 64, and 17.6% 65 or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.3 males.

The median household income was $35,688 and the median family income was $45,315. Males had a median income of $32,800 versus $23,835 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,113. About 8.8% of families and 12.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.5% of those under age 18 and 10.6% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Local businesses

- Marshalltown Company, a manufacturer of American tools for many construction and archaeological applications, is based in Marshalltown.

- The Big Treehouse, a large tourist attraction located outside of Marshalltown.

Top employers

According to Marshalltown's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[35] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | JBS USA (formerly Swift & Company) | 2,270 |

| 2 | Emerson Electric - Fisher Flow Controls | 1,135 |

| 3 | Marshalltown Community School District | 950 |

| 4 | Lennox Industries, Inc. | 915 |

| 5 | Iowa Veterans Home | 865 |

| 6 | UnityPoint Health | 400 |

| 7 | Hy-Vee | 340 |

| 8 | Walmart | 300 |

| 9 | Marshalltown Community College | 245 |

| 10 | City of Marshalltown | 199 |

| 11 | McFarland Clinic PC | 185 |

| 12 | Marshall County | 183 |

Education

Marshalltown Community School District serves Marshalltown.

The first schoolhouse in Marshalltown was a log cabin built in 1853. The building stood on Main Street between Third and Fourth Streets. Neary Hoxie served as the first teacher.[36]

In 1874, high school classes were held in an old building on North Center Street. The high school had 45 students and C. P. Rogers served as the school's superintendent.[36]

As of 2020, there are multiple schools in Marshalltown. There are six elementary schools, one intermediate school, a Catholic school (PreK–6) and Christian school (1–8), and a middle school (7–8). There is also Marshalltown High School, with over 1,000 students. East Marshall Community School District serves small portions of the Marshalltown city limits.[37] The district was established on July 1, 1992 by the merger of the LDF and SEMCO school districts.[38] The BCLUW Community School District serves some rural areas nearby Marshalltown.[39]

Infrastructure

Transportation

![]() U.S. Route 30 bypasses the town to the south, while

U.S. Route 30 bypasses the town to the south, while ![]() Iowa Highway 14 runs through the center of town. An expressway,

Iowa Highway 14 runs through the center of town. An expressway, ![]() Iowa Highway 330 connects Marshalltown to Des Moines.

Iowa Highway 330 connects Marshalltown to Des Moines.

Marshalltown has bus (Marshalltown Municipal Transit or MMT) and taxicab services. It is also served by Trailways Coach Nationwide.

A municipal airport serves the county, approximately four miles north of town. The closest commercial airport is Des Moines International Airport, 53 miles (85.3 km) miles to the southwest.

There currently is no passenger rail service.

Notable people

- Cap Anson, Major League Baseball player and manager, Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939[40]

- Matthew Bucksbaum, businessman and philanthropist: with brothers Martin and Maurice co-founded General Growth Properties greatly accelerating modern post-war suburbanization[41]

- Jerry Burke, pianist and organist from The Lawrence Welk Show

- Blean Calkins, radio sportscaster, president of National Sportscasters & Sportswriters Association 1979-1981

- Edwin N. Chapin (1823–1896), postmaster and newspaper publisher

- Nettie Sanford Chapin (1830–1901), teacher, historian, author, newspaper publisher, suffragist

- Jeff Clement, baseball player for University of Southern California, Pittsburgh Pirates and Minnesota Twins

- T. Nelson Downs, stage magician also known as "King of Koins"

- Jim Dunn, former owner of MLB's Cleveland Indians

- Joseph Carlton Petrone, US Ambassador to the United Nations Office at Geneva[42]

- George Gardner Fagg, United States federal appellate judge[43]

- Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher (1885–1973), commander during Battle of the Coral Sea and Battle of Midway[44]

- Benjamin T. Frederick, U.S. Representative, Marshalltown city councilman

- Ben Hanford (1861-1910), two-time Socialist Party candidate for Vice President of the United States[45]

- Frank Hawks, record-breaking aviator during 1920s and 1930s

- Anna Arnold Hedgeman (1899–1990), African American civil rights leader[46][47]

- Clifford B. Hicks (1920-2010), children's book author

- Wally Hilgenberg (1942–2008), football player[48]

- Mary Beth Hurt (1946– ), film, television and stage actress, 3-time Tony Award nominee

- Toby Huss (1966– ), actor and voice actor, Adventures of Pete and Pete, National Lampoon's Vegas Vacation, King of the Hill, Halt and Catch Fire

- Laurence C. Jones (1884–1975), founder of Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi[49]

- Lance Corporal Darwin Judge (1956–1975), one of last two soldiers killed in Vietnam War

- Noel T. Keen, plant physiologist

- Maury Kent (1885-1966), MLB player, Iowa, Iowa State and Northwestern coach

- Joseph Kosinski (1974– ), director of Disney film Tron Legacy[50]

- Richard W. Lariviere (1950– ), president and CEO of Field Museum of Natural History[51]

- Milo Lemert (1890–1918), received Medal of Honor for actions during World War I[52]

- Dave Lennox, inventor and businessman, founded Lennox furnace manufacturing business in Marshalltown in 1895

- Meridean Maas (1934-2020), nurse, nursing professor at University of Iowa

- Vera McCord (1870s-1949), actress and film director, born in Marshalltown[53]

- Elizabeth Ruby Miller (1905-1988), state legislator[54]

- Merle Miller (1919-1986), novelist, activist

- Modern Life is War, hardcore punk band

- Allie Morrison (1904–1966), wrestler, world and Olympic champion[55]

- Stephen B. Packard (1839–1922), Governor of Louisiana briefly in 1877[56]

- Jim Rayburn (1909–1970), founder of Young Life[57]

- Adolph Rupp (1901–1977), Hall of Fame college basketball coach, once head coach at Marshalltown High School

- Jean Seberg (1938-1979), actress, star of such films as Saint Joan, Breathless, Paint Your Wagon and Airport

- Lee Paul Sieg, former president of University of Washington

- Jimmy Siemers, (1982-), professional water skier[58]

- Jeanne Rowe Skinner - American U.S. Navy officer and former First Lady of Guam. [59][60]

- Wynn Speece (1917–2007), "Neighbor Lady" on WNAX (AM) for 64 years[61]

- Billy Sunday (1862–1935), Major League Baseball player and Christian evangelist of early 20th Century[12][62]

- Henry Haven Windsor (1859–1924), author, magazine editor, publisher, founder and first editor of Popular Mechanics[63]

- Michelle Vieth, Mexican-American actress, born in Marshalltown

- Peter Zeihan (1973–), geopolitical strategist, author, and speaker

Sister city relations

Budyonnovsk, Stavropol Krai, Russia.[64]

Budyonnovsk, Stavropol Krai, Russia.[64] Minami-Alps, Yamanashi, Japan

Minami-Alps, Yamanashi, Japan

References

- ^ "City-Data". Marshaltown. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ "MAYOR & City Council | Marshalltown, IA". www.marshalltown-ia.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ a b "2020 Census State Redistricting Data". census.gov. United states Census Bureau. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "History". Marshalltown Iowa Community Link. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ "Henry Anson". Anson Elementary School. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ Chicago and North Western Railway Company (1908). A History of the Origin of the Place Names Connected with the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railways. p. 99.

- ^ "Cap Anson". Society for American Baseball Research Baseball Biography Project. Archived from the original on 2012-01-07. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ "The First Son". Cap Chronicled. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ Firstenberger, William Andrew (2005). In rare form: a pictorial history of baseball evangelist Billy Sunday. University of Iowa Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-87745-959-2. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ a b Dorsett, 15; Knickerbocker, 26-7.

- ^ Storm Data Publication | IPS | National Climatic Data Center (NCDC). www.ncdc.noaa.gov (Report). Retrieved 23 July 2020."Iowa F3". Tornado History Projects. Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved 24 July 2020.Iowa Event Report: F3 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 24 July 2020.Iowa Event Report: F3 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Iowa Event Report: EF3 Tornado. National Centers for Environmental Information (Report). National Weather Service. Retrieved 15 February 2021.""It's right over us": Tornadoes strike parts of Iowa, injuring several, leaving path of destruction". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Midwest Derecho Causes Widespread Damage; More Than 1 Million Homes and Businesses Lose Power". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- ^ Joens, Philip; Sahouri, Andrea May; Eller, Donnelle (2020-08-10). "Derecho sends straight-line winds through Iowa, leaving hundreds of thousands without power". Des Moines Register. Retrieved 2020-08-15.

- ^ Bradstream, Lana (2020-08-11). "Storm unleashes fury on Marshalltown". Times-Republican. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-15.

- ^ "Alliant Energy on Twitter: "Progress continues. 99% of our customers impacted by #StormDerecho on Aug. 10 have power available again. Fewer than 1,000 are without service at this time – and we are committed to getting power restored for all. Thank you for your ongoing patience and support. #IowaStrong t.co/42TjkjXyyi" / Twitter". Twitter. 23 Aug 2020. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ^ James, Kayla (2020-08-18). "One week after derecho, thousands still wait for power in Marshalltown". KCCI. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ Rohlfing, Noah (19 Aug 2020). "'Extensive' derecho damage big setback for Conservation Board". timesrepublican.com. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- ^ "Midwest: Hispanic Migrants - Rural Migration News | Migration Dialogue". Rural Migration News. 2013. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Refugees happy in Marshalltown". timesrepublican.com/. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ^ "Talk of immigration raids a concern for some local officials". timesrepublican.com/. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- ^ Flora, Jan; Prado-Meza, Claudia; Lewis, Hannah (2011). "After the Raid Is Over: Marshalltown, Iowa and the Consequences of Worksite Enforcement Raids" (PDF). Immigration Policy Center Special Report.

- ^ Kranish, Michael (2018). "Whitaker's role in 2006 immigration raid foreshadowed aggressive stance as acting attorney general". Washington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Marshalltown, IA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Marshalltown city, Iowa; Iowa". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ^ a b "Demographic Profiles". Iowa Data Center. 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bureau, US Census. "1990 Census of Population: General Population Characteristics". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ City of Marshalltown CAFR

- ^ a b Fosness, Irene Marshalltown: A Pictorial History, Quest Publishing, 1985.

- ^ "East Marshall" (PDF). Iowa Department of Education. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ^ "REORGANIZATION & DISSOLUTION ACTIONS SINCE 1965-66" (PDF). Iowa Department of Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-09. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ "Positions Available." BCLUW Community School District. Retrieved on August 3, 2015. "Serving the areas of [...] rural Marshalltown,[...]" and "BCLUW School District" (PDF). Iowa Department of Education. Retrieved 2020-03-22. - The map shows that none of the Marshalltown city limits is within the BCLUW district.

- ^ "The Baseball Biography Project". "Cap Anson" by David Fleitz. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (November 29, 2013). "Matthew Bucksbaum, Mall Developer, Dies at 87". New York Times. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Reagan, Ronald (1989). Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Ronald Reagan, 1987. Best Books. p. 36. ISBN 9781623769505.

- ^ Who's Who In Government, p. 1977, vol. 3, p. 181. Marquis Who's Who. November 1977. ISBN 9780837912035. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ "Arlington National Cemetery". Frank Jack Fletcher, Admiral. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Joshua Wanhope, "Biographical Sketch of Ben Hanford," in Ben Hanford, Fight For Your Life! Recording Some Activities of a Labor Agitator. New York: Wilshire Book Co., 1909; pp. 3-4.

- ^ Cook, Joan (January 26, 1990). "Anna Hedgeman Is Dead at 90; Aide to Mayor Wagner in 1950's". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ "Anna Hedgeman was a force civil rights". African American Rrgistry. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ "Wally Hilgenberg". National Football League. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Schmidt, D.A. (2002) Iowa Pride. Xulon Press. p 210.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (December 3, 2010). "Cyberspace Gamble". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Our Staff, The Field Museum

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients World War I". U.S. Army Center Of Military History. December 3, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Christina Lane, "Vera McCord" in Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project, Center for Digital Research and Scholarship, Columbia University Libraries, 2013.

- ^ 'Elizabeth R. Miller, 83,' The Marshalltown Times Republican, January 3, 1989, pg. 3

- ^ "SPORTS-REFERENCE". Olympic Sports/Allie Morrison. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Mill, George Rogues and Heroes from Iowa's Amazing Past The Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1972.

- ^ Rayburn, Jim. "Jim Jr, Founder of Young Life - Jim Rayburn Website".

- ^ "2007 World Ranking List, Men’s Jump, List generated on: November 1, 2005 to October 31, 2006,

- ^ "Ensign Jeanne Rowe Bride Of Lieut. Carleton Skinner". newspapers.com. The Lincoln Star. May 1, 1943. Retrieved November 2, 2021.(archived)

- ^ "Obituary - Jeanne R. Skinner". The Marin Independent Journal. April 23, 1988. Retrieved November 2, 2021.(archived)

- ^ "The Neighbor Lady - Radio 570 WNAX - Page 3115643".

- ^ Firstenberger, William Andrew (2005). In rare form: a pictorial history of baseball evangelist Billy Sunday. University of Iowa Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-87745-959-2. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Whittaker, Wayne (January 1952). The Story of Popular Mechanics. Popular Mechanics. pp. 127ff. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Ames, Iowa". Open World Leadership Center. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.