Particle physics: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: Mobile edit |

|||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

Another major effort is in model building where [[model building (particle physics)|model builders]] develop ideas for what physics may lie [[beyond the Standard Model]] (at higher energies or smaller distances). This work is often motivated by the [[hierarchy problem]] and is constrained by existing experimental data. It may involve work on [[supersymmetry]], alternatives to the [[Higgs mechanism]], extra spatial dimensions (such as the [[Randall-Sundrum]] models), [[Preon]] theory, combinations of these, or other ideas. |

Another major effort is in model building where [[model building (particle physics)|model builders]] develop ideas for what physics may lie [[beyond the Standard Model]] (at higher energies or smaller distances). This work is often motivated by the [[hierarchy problem]] and is constrained by existing experimental data. It may involve work on [[supersymmetry]], alternatives to the [[Higgs mechanism]], extra spatial dimensions (such as the [[Randall-Sundrum]] models), [[Preon]] theory, combinations of these, or other ideas. |

||

A third major effort in theoretical particle physics is [[string theory]]. ''String theorists'' attempt to construct a unified description of [[quantum mechanics]] and [[general relativity]] by building a theory based on small strings, and [[branes]] rather than particles. If the theory is successful, it may be considered a "[[Theory of Everything]]" |

A third major effort in theoretical particle physics is [[string theory]]. ''String theorists'' attempt to construct a unified description of [[quantum mechanics]] and [[general relativity]] by building a theory based on small strings, and [[branes]] rather than particles. If the theory is successful, it may be considered a "[[Theory of Everything]]": |

||

€{[£]} (¥*2) pi (cos) |

|||

There are also other areas of work in theoretical particle physics ranging from particle cosmology to [[loop quantum gravity]]. |

There are also other areas of work in theoretical particle physics ranging from particle cosmology to [[loop quantum gravity]]. But string theory is the obvious choice for the future of physics. |

||

This division of efforts in particle physics is reflected in the names of categories on the [[arXiv]], a [[preprint]] archive:<ref>[http://www.arxiv.org arxiv.org]</ref> hep-th (theory), hep-ph (phenomenology), hep-ex (experiments), hep-lat ([[lattice gauge theory]]). |

This division of efforts in particle physics is reflected in the names of categories on the [[arXiv]], a [[preprint]] archive:<ref>[http://www.arxiv.org arxiv.org]</ref> hep-th (theory), hep-ph (phenomenology), hep-ex (experiments), hep-lat ([[lattice gauge theory]]). |

||

Revision as of 04:42, 29 August 2013

| Standard Model of particle physics |

|---|

|

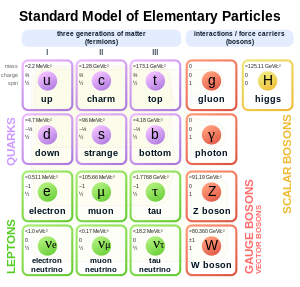

Particle physics is a branch of physics which studies the nature of particles that are the constituents of what is usually referred to as matter and radiation. In current understanding, particles are excitations of quantum fields and interact following their dynamics. Although the word "particle" can be used in reference to many objects (e.g. a proton, a gas particle, or even household dust), the term "particle physics" usually refers to the study of the fundamental objects of the universe – fields that must be defined in order to explain the observed particles, and that cannot be defined by a combination of other fundamental fields. The current set of fundamental fields and their dynamics are summarized in a theory called the Standard Model, therefore particle physics is largely the study of the Standard Model's particle content and its possible extensions.

Subatomic particles

Modern particle physics research is focused on subatomic particles, including atomic constituents such as electrons, protons, and neutrons (protons and neutrons are composite particles called baryons, made of quarks), produced by radioactive and scattering processes, such as photons, neutrinos, and muons, as well as a wide range of exotic particles. To be specific, the term particle is a misnomer from classical physics because the dynamics of particle physics are governed by quantum mechanics. As such, they exhibit wave-particle duality, displaying particle-like behavior under certain experimental conditions and wave-like behavior in others. In more technical terms, they are described by quantum state vectors in a Hilbert space, which is also treated in quantum field theory. Following the convention of particle physicists, elementary particles refer to objects such as electrons and photons as it is well known that those types of particles display wave-like properties as well.

| Types | Generations | Antiparticle | Colors | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quarks | 2 | 3 | Pair | 3 | 36 |

| Leptons | 2 | 3 | Pair | None | 12 |

| Gluons | 1 | 1 | Own | 8 | 8 |

| W | 1 | 1 | Pair | None | 2 |

| Z | 1 | 1 | Own | None | 1 |

| Photon | 1 | 1 | Own | None | 1 |

| Higgs | 1 | 1 | Own | None | 1 |

| Total | 61 | ||||

All particles, and their interactions observed to date, can be described almost entirely by a quantum field theory called the Standard Model.[1] The Standard Model has 61 elementary particles.[2] Those elementary particles can combine to form composite particles, accounting for the hundreds of other species of particles that have been discovered since the 1960s. The Standard Model has been found to agree with almost all the experimental tests conducted to date. However, most particle physicists believe that it is an incomplete description of nature, and that a more fundamental theory awaits discovery (See Theory of Everything). In recent years, measurements of neutrino mass have provided the first experimental deviations from the Standard Model.

History

| Modern physics |

|---|

| |

The idea that all matter is composed of elementary particles dates to at least the 6th century BC.[3] The philosophical doctrine of atomism and the nature of elementary particles were studied by ancient Greek philosophers such as Leucippus, Democritus, and Epicurus; ancient Indian philosophers such as Kanada, Dignāga, and Dharmakirti; Muslim scientists such as Ibn al-Haytham, Ibn Sina, and Mohammad al-Ghazali; and in early modern Europe by physicists such as Pierre Gassendi, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton. The particle theory of light was also proposed by Ibn al-Haytham, Ibn Sina, Gassendi, and Newton. Those early ideas were founded through abstract, philosophical reasoning rather than experimentation and empirical observation.

In the 19th century, John Dalton, through his work on stoichiometry, concluded that each element of nature was composed of a single, unique type of particle. Dalton and his contemporaries believed those were the fundamental particles of nature and thus named them atoms, after the Greek word atomos, meaning "indivisible".[4] However, near the end of that century, physicists discovered that atoms are not, in fact, the fundamental particles of nature, but conglomerates of even smaller particles. The early 20th-century explorations of nuclear physics and quantum physics culminated in proofs of nuclear fission in 1939 by Lise Meitner (based on experiments by Otto Hahn), and nuclear fusion by Hans Bethe in that same year. Those discoveries gave rise to an active industry of generating one atom from another, even rendering possible (although it will probably never be profitable) the transmutation of lead into gold; and, those same discoveries also led to the development of nuclear weapons. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, a bewildering variety of particles were found in scattering experiments. It was referred to as the "particle zoo". That term was deprecated after the formulation of the Standard Model during the 1970s in which the large number of particles was explained as combinations of a (relatively) small number of fundamental particles.

Standard Model

The current state of the classification of all elementary particles is explained by the Standard Model. It describes the strong, weak, and electromagnetic fundamental interactions, using mediating gauge bosons. The species of gauge bosons are the gluons,

W−

,

W+

and

Z

bosons, and the photons.[1] The Standard Model also contains 24 fundamental particles, (12 particles and their associated anti-particles), which are the constituents of all matter.[5] Finally, the Standard Model also predicted the existence of a type of boson known as the Higgs boson. Early in the morning on July 4, 2012, physicists with the Large Hadron Collider at CERN announced they have found a new particle that behaves similarly to what is expected from the Higgs boson.[6]

Experimental laboratories

In particle physics, the major international laboratories are located at the:

- Brookhaven National Laboratory (Long Island, United States). Its main facility is the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), which collides heavy ions such as gold ions and polarized protons. It is the world's first heavy ion collider, and the world's only polarized proton collider.[7][failed verification]

- Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics (Novosibirsk, Russia). Its main projects are now the electron-positron colliders VEPP-2000,[8] operated since 2006, and VEPP-4,[9] started experiments in 1994. Earlier facilities include the first electron-electron beam-beam collider VEP-1, which conducted experiments from 1964 to 1968; the electron-positron colliders VEPP-2, operated from 1965 to 1974; and, its successor VEPP-2M,[10] performed experiments from 1974 to 2000.[11]

- CERN, (Franco-Swiss border, near Geneva). Its main project is now the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which had its first beam circulation on 10 September 2008, and is now the world's most energetic collider of protons. It also became the most energetic collider of heavy ions after it began colliding lead ions. Earlier facilities include the Large Electron–Positron Collider (LEP), which was stopped on November 2, 2000 and then dismantled to give way for LHC; and the Super Proton Synchrotron, which is being reused as a pre-accelerator for the LHC.[12]

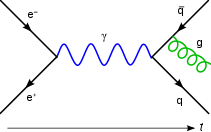

- DESY (Hamburg, Germany). Its main facility is the Hadron Elektron Ring Anlage (HERA), which collides electrons and positrons with protons.[13]

- Fermilab, (Batavia, United States). Its main facility until 2011 was the Tevatron, which collided protons and antiprotons and was the highest-energy particle collider on earth until the Large Hadron Collider surpassed it on 29 November 2009.[14]

- KEK, (Tsukuba, Japan). It is the home of a number of experiments such as the K2K experiment, a neutrino oscillation experiment and Belle, an experiment measuring the CP violation of B mesons.[15]

Many other particle accelerators do exist.

The techniques required to do modern, experimental, particle physics are quite varied and complex, constituting a sub-specialty nearly completely distinct from the theoretical side of the field.

Theory

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

Theoretical particle physics attempts to develop the models, theoretical framework, and mathematical tools to understand current experiments and make predictions for future experiments. See also theoretical physics. There are several major interrelated efforts being made in theoretical particle physics today. One important branch attempts to better understand the Standard Model and its tests. By extracting the parameters of the Standard Model, from experiments with less uncertainty, this work probes the limits of the Standard Model and therefore expands our understanding of nature's building blocks. Those efforts are made challenging by the difficulty of calculating quantities in quantum chromodynamics. Some theorists working in this area refer to themselves as phenomenologists and they may use the tools of quantum field theory and effective field theory. Others make use of lattice field theory and call themselves lattice theorists.

Another major effort is in model building where model builders develop ideas for what physics may lie beyond the Standard Model (at higher energies or smaller distances). This work is often motivated by the hierarchy problem and is constrained by existing experimental data. It may involve work on supersymmetry, alternatives to the Higgs mechanism, extra spatial dimensions (such as the Randall-Sundrum models), Preon theory, combinations of these, or other ideas.

A third major effort in theoretical particle physics is string theory. String theorists attempt to construct a unified description of quantum mechanics and general relativity by building a theory based on small strings, and branes rather than particles. If the theory is successful, it may be considered a "Theory of Everything": €{[£]} (¥*2) pi (cos)

There are also other areas of work in theoretical particle physics ranging from particle cosmology to loop quantum gravity. But string theory is the obvious choice for the future of physics.

This division of efforts in particle physics is reflected in the names of categories on the arXiv, a preprint archive:[16] hep-th (theory), hep-ph (phenomenology), hep-ex (experiments), hep-lat (lattice gauge theory).

Practical applications

In principle, all physics (and practical applications developed therefrom) can be derived from the study of fundamental particles. In practice, even if "particle physics" is taken to mean only "high-energy atom smashers", many technologies have been developed during these pioneering investigations that later find wide uses in society. Cyclotrons are used to produce medical isotopes for research and treatment (for example, isotopes used in PET imaging), or used directly for certain cancer treatments. The development of Superconductors has been pushed forward by their use in particle physics. The World Wide Web and touchscreen technology were initially developed at CERN.

Additional applications are found in medicine, national security, industry, computing, science, and workforce development, illustrating a long and growing list of beneficial practical applications with contributions from particle physics.[17]

Future

The primary goal, which is pursued in several distinct ways, is to find and understand what physics may lie beyond the standard model. There are several powerful experimental reasons to expect new physics, including dark matter and neutrino mass. There are also theoretical hints that this new physics should be found at accessible energy scales. Furthermore, there may be surprises that will give us opportunities to learn about nature.

Much of the effort to find this new physics are focused on new collider experiments. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was completed in 2008 to help continue the search for the Higgs boson, supersymmetric particles, and other new physics. An intermediate goal is the construction of the International Linear Collider (ILC), which will complement the LHC by allowing more precise measurements of the properties of newly found particles. In August 2004, a decision for the technology of the ILC was taken but the site has still to be agreed upon.

In addition, there are important non-collider experiments that also attempt to find and understand physics beyond the Standard Model. One important non-collider effort is the determination of the neutrino masses, since these masses may arise from neutrinos mixing with very heavy particles. In addition, cosmological observations provide many useful constraints on the dark matter, although it may be impossible to determine the exact nature of the dark matter without the colliders. Finally, lower bounds on the very long lifetime of the proton put constraints on Grand Unified Theories at energy scales much higher than collider experiments will be able to probe any time soon.

See also

- Atomic physics

- High pressure

- International Conference on High Energy Physics

- Introduction to quantum mechanics

- List of accelerators in particle physics

- List of particles

- Magnetic monopole

- Micro black hole

- Resonance (particle physics)

- Self-consistency principle in high energy Physics

- Non-extensive self-consistent thermodynamical theory

- Standard Model (mathematical formulation)

- Stanford Physics Information Retrieval System

- Timeline of particle physics

- Unparticle physics

References

- ^ a b "Particle Physics and Astrophysics Research". The Henryk Niewodniczanski Institute of Nuclear Physics. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^

S. Braibant, G. Giacomelli, M. Spurio (2009). Particles and Fundamental Interactions: An Introduction to Particle Physics. Springer. pp. 313–314. ISBN 978-94-007-2463-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fundamentals of Physics and Nuclear Physics" (PDF). Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "Scientific Explorer: Quasiparticles". Sciexplorer.blogspot.com. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Nakamura, K (1 July 2010). "Review of Particle Physics". Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics. 37 (7A): 075021. Bibcode:2010JPhG...37g5021N. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/37/7A/075021.

- ^ http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/07/higgs-boson-discovery/

- ^ "Brookhaven National Laboratory - A Passion for Discovery". Bnl.gov. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "index". Vepp2k.inp.nsk.su. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "The VEPP-4 accelerating-storage complex". V4.inp.nsk.su. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "VEPP-2M collider complex" (in Template:Ru icon). Inp.nsk.su. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "The Budker Institute Of Nuclear Physics". English Russia. 21 January 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to". Info.cern.ch. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "Germany's largest accelerator centre - Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY". Desy.de. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "Fermilab | Home". Fnal.gov. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "Kek | High Energy Accelerator Research Organization". Legacy.kek.jp. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ arxiv.org

- ^ "Fermilab | Science at Fermilab | Benefits to Society". Fnal.gov. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

Further reading

- Introductory reading

- Frank Close (2004) Particle Physics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280434-0.

- Close, Frank; Marten, Michael; Sutton, Christine (2004). The particle odyssey: a journey to the heart of the matter. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198609438.

- Ford, Kenneth W. (2005) The Quantum World. Harvard Univ. Press.

- Oerter, Robert (2006) The Theory of Almost Everything: The Standard Model, the Unsung Triumph of Modern Physics. Plume.

- Schumm, Bruce A. (2004) Deep Down Things: The Breathtaking Beauty of Particle Physics. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8018-7971-X.

- Riazuddin, PhD. "An Overview of Particle Physics and Cosmology". NCP Journal of Physics. 1 (1). Dr. Professor Riazuddin, High Energy Theory Group, and senior scientist at the National Center for Nuclear Physics: 50.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Frank Close (2006) The New Cosmic Onion. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-58488-798-2.

- Advanced reading

- Robinson, Matthew B., Gerald Cleaver, and J. R. Dittmann (2008) "A Simple Introduction to Particle Physics" - Part 1, 135pp. and Part 2, nnnpp. Baylor University Dept. of Physics.

- Griffiths, David J. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. Wiley, John & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- Kane, Gordon L. (1987). Modern Elementary Particle Physics. Perseus Books. ISBN 0-201-11749-5.

- Perkins, Donald H. (1999). Introduction to High Energy Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62196-8.

- Povh, Bogdan (1995). Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-59439-6.

- Boyarkin, Oleg (2011). Advanced Particle Physics Two-Volume Set. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-0412-4.

External links

- Symmetry magazine

- Fermilab

- Particle physics – it matters - the Institute of Physics

- Nobes, Matthew (2002) "Introduction to the Standard Model of Particle Physics" on Kuro5hin: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3a, Part 3b.

- CERN - European Organization for Nuclear Research

- The Particle Adventure - educational project sponsored by the Particle Data Group of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL)