Royal Alexandra Theatre

RA, Royal Alexandra Theatre | |

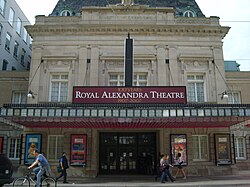

The Royal Alexandra Theatre in 2012 | |

| |

| Location | Toronto, Ontario |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43°38′50″N 79°23′15″W / 43.64722°N 79.38750°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Mirvish Productions |

| Capacity | 1,244 |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1907 |

| Architect | John M. Lyle |

| Website | |

| mirvish.com/royal-alexandra-theatre | |

| Designated | 1986 |

The Royal Alexandra Theatre, commonly known as the Royal Alex, is an historic performing arts theatre in Toronto, Ontario. The theatre is located at 260 King Street West, in the downtown Toronto Entertainment District. Owned and operated by Mirvish Productions, the theatre has approximately 1,244 seats across three levels. Built in 1907, the Royal Alexandra Theatre is the oldest continuously operating legitimate theatre in North America.[1]

History

[edit]The Royal Alex is a 1,244-seat, beaux-arts style, proscenium-stage theatre, with two balcony levels, built in the style typical of 19th century British theatres. Construction began in 1905 and was completed in 1907. Since 1963 it has been owned by Ed Mirvish Enterprises, a company established by Toronto department store owner Edwin Mirvish. Since 1986, the theatre has been managed and operated by Mirvish Productions, the theatre production company headed by Ed's son, David Mirvish. The theatre, commonly known as the "Royal Alex", "the Alex" or "the R.A.T." is named for Queen Alexandra, a Danish princess who was the wife of King Edward VII, and the great-great-grandmother of the current King of Canada, Charles III. The theatre received letters patent from Edward VII entitling it to the royal designation. Its present owners believe that it is the only remaining legally "royal theatre" in North America.

At the time of its opening, the Royal Alex was in an upscale neighbourhood. The mansion of Ontario's lieutenant-governor was nearby, the Ontario legislative buildings had been there until 1893, the upper-class St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church and the Princess Theatre, Toronto's finest "first-class" showplace were also in the vicinity. The theatre was built on what had previously been the athletic field of the exclusive boys' school Upper Canada College near the corner of King and Simcoe streets. This intersection was then known as "the crossroads of Education, Legislation, Salvation and Damnation" - "Education" for Upper Canada College; "Legislation" for the parliament buildings; "Salvation" for St. Andrew's; and "Damnation" for a tavern, popular with actors from the Princess Theatre, that then stood on the northeast corner of the crossroads.

The construction of the Royal Alex was financed by a group of business leaders who sought to "put Toronto on the map" as a place of culture and refinement. The principal of this group was Cawthra Mulock, a 21-year-old foundry owner, scion of two of Ontario's most prominent families (the Cawthras and the Mulocks) who lived a short walk east of site in a large home called "Cawthra House", locally famed for its doorknobs of solid gold. Other members of the syndicate included Robert Alexander Smith, Stephen Haas, and Lawrence "Lol" Solman. Solman would manage the theatre from 1907 until his death in 1931.

The architect chosen by Mulock and his group was the young John McIntosh Lyle, born in Belfast, reared in Hamilton, Ontario, and educated at Yale University and Paris' École des Beaux-Arts. Lyle was an associate with the New York architectural firm Carrère and Hastings, the official architects of the theatre. Mulock gave Lyle a budget of $750,000 and the simple instruction "Build me the finest theatre on the continent." He also, however, insisted that the theatre be built on a steel frame, as a demonstration of the products of his foundry.

Lyle greatly overspent his budget, but delivered a structure described in later years as "an Edwardian jewel-box." The interior featured an Italian marble lobby; Venetian mosaic floors; elaborately carved walnut and cherrywood stairs and railings; silk wallpapers; ornate, gilded plasterwork; and an enormous sounding-board mural ("Venus and Attendants Discover the Sleeping Adonis") by the popular Canadian painter Frederick S. Challener. Lyle also incorporated a number of "firsts" into his design: the Alex was North America's first air-conditioned theatre (by virtue of a large ice-pit under the orchestra), one of its first "fireproof" theatres, and the first on the continent (thanks to the steel framing) to employ cantilevered balconies, with no internal pillars to interfere with lines of sight.

The theatre opened on August 26, 1907. Its first presentation was a pantomime "spectacle" titled "Top O'Th' World", starring Anna Laughlin, heading a cast of 65. During its early years, the Royal Alex had great difficulty in booking acts for its stage. The theatre owners found themselves at odds with the powerful Theatrical Syndicate, the New York-based organisation headed by Charles Frohman, Al Hayman, Abe Erlanger, Mark Klaw, Samuel F. Nixon and Fred Zimmerman that not only exercised a near monopoly on touring theatre in North America, but also had a financial interest in the rival Princess Theatre, two blocks east of the Royal Alexandra. The manager of the Alex, Lawrence "Lol" Solman, allied his theatre with the Syndicate's chief challengers, the Shubert brothers. For this impertinence, Solman later wrote, Abe Erlanger threatened to drive the Alex into bankruptcy and turn it into a stable for the horses of the carriage-trade patrons of the Princess.

The local rivalry with the Princess Theatre ended on the night of May 7, 1915, when a fire gutted that theatre, leaving the Royal Alex as Toronto's only first-class, legitimate playhouse. By coincidence, on that same evening, the British liner Lusitania sank in the Irish Sea after being struck by a torpedo. One of those killed in the disaster was Syndicate partner and creative head Charles Frohman.

Over the 1940s and '50s, the Royal Alex declined - as did so many regional theatres, unable to compete with cinema, radio and television - into hard times. The neighbourhood surrounding the theatre also went into decline, becoming dominated by railway marshalling yards, warehouses and light industry that had moved to the area following the Great Toronto Fire of 1904. In 1962, after a decade of money-losing operation, the trustees of the Mulock estate (Cawthra Mulock died during the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918) put the theatre up for sale. The theatre was to have been demolished for a parking lot.[2] The property was purchased by Ed Mirvish in 1963, owner of the Toronto discount shop Honest Ed's for the sum of $250,000.[3] Mirvish said at the time that he knew nothing about theatre—had never even been inside a theatre—but knew a bargain when he saw one.

As a condition of the sale, Ed Mirvish pledged to continue operating the Royal Alex as a legitimate theatre for at least five years. If, at the end of that time, he was unwilling to continue, he was then permitted to demolish the building and use the site for other purposes. Mirvish closed the theatre for one year - the longest it had ever been dark - for renovation and restoration. The Royal Alex re-opened in September, 1963, with the comedy "Never Too Late", starring William Bendix and produced by Ed Mirvish.

Ed Mirvish rarely after ventured into production, but used the theatre - as it had always been used - as a road house, booking in touring shows and pre-Broadway tryouts. He also allowed the theatre to be used by local companies - including the Canadian Opera Company and the National Ballet of Canada - and made the Alex the home, for many years, of the popular annual Toronto revue "Spring Thaw". He did, however, achieve notable success as a producer with Hair in 1970, and Godspell in 1972. The latter starred a group of young Canadian unknowns who would go on to great success, including Victor Garber, Gilda Radner, Martin Short, Eugene Levy and Andrea Martin.

Following the renovation of the Royal Alex, Mirvish purchased, one by one, the warehouse and industrial buildings along King St. to the west of the theatre. In these, he opened a group of colourful restaurants—including Ed's Warehouse, Ed's Folly and Old Ed's—in a successful effort to draw people back into the neighbourhood. The last of these restaurants closed in 2000 by which point the area around the Royal Alex had been transformed from abandoned warehouses into a district of independent winebars, restaurants, cafes and bistros.

In 1975, Toronto City Council recognized the historic value of the theatre by designating it under the Ontario Heritage Act by By-law 512-75.[4] In 1987, on the 80th anniversary of the theatre, it was designated a National Historic Site of Canada.[5][6]

Ed Mirvish and his son David Mirvish, added a second theatre to the family interests in 1982, when they purchased and restored London, England's historic Old Vic. In 1986, David Mirvish created the company Mirvish Productions to produce original, "sit-down" plays and musicals for the Royal Alexandra. Ed Mirvish retired from active participation in the theatres in 1987, handing the business to his son. In 1993, David Mirvish added a third theatre to the empire, building the Princess of Wales Theatre a block to the west of the Royal Alexandra. The Princess was named, in part, in memory of the old Princess, rival to the Alex in the early years of the 20th century.

The theatre's managers have been Lawrence Solman 1907-1931, William Breen 1933-1939, Ernest Rawley 1939-1963, Edwin De Rocher 1963-1969, Yale Simpson 1969-1989, Graham Hall 1989-1994, Ron Jacobson 1994–present.

2016 renovation

[edit]On May 15, 2016, following the conclusion of Kinky Boots' run at the theatre, the Royal Alexandra closed to undergo a $2.5 million renovation. David Mirvish explained that the renovation was intended to "once more restore and give life to that sparkle and give a level of comfort that will preserve the theatre as our flagship of the 21st century". The most significant change was the refurbishment of its seating areas to improve audience comfort, with the replacement of its original seats with modern versions that are larger and arranged to increase legroom. The new seating layout necessitated a reduction in capacity from 1,497 to 1,244; David contrasted it to the trend of theatres increasing their capacity to "maximize" revenue, arguing that the improved amenities would build improve customer loyalty and encourage repeat visits.[7]

The theatre re-opened on November 15, 2016 with the opening of Come from Away; the pre-Broadway run for the show set sales records for the Royal Alex, selling out its entire run within only its second week of shows, and $1.7 million worth of tickets in a week.[8][9][10]

Notable people who have performed at the Royal Alex

[edit]- Lucille Ball

- James Randi

- Lady Gaga[11]

- Johnston Forbes-Robertson and Gertrude Elliott

- Mary Pickford

- Fred and Adele Astaire

- E. H. Sothern and Julia Marlowe

- Margaret Anglin

- Tallulah Bankhead

- Fanny Brice

- The Marx Brothers

- Mae West

- Alla Nazimova

- Theda Bara

- Eddie Cantor

- Maurice Chevalier

- Marie Dressler

- Margot Fonteyn

- George Formby

- Al Jolson

- Harry Lauder

- Beatrice Lillie

- Ruth Gordon

- Maurice Evans

- Helen Hayes

- John Barrymore

- Ethel Barrymore

- Katharine Cornell

- Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy

- Alicia Markova

- Ingrid Bergman

- John Gielgud

- Ralph Richardson

- Peggy Ashcroft

- Deborah Kerr

- Édith Piaf

- Paul Robeson

- Orson Welles

- Maggie Smith

- Ethel Waters

- Alan Bates

- Derek Jacobi

- Raymond Burr

- Joanne Woodward

- Gilda Radner

- Victor Garber

- Kevin Smith

- Eugene Levy

- Martin Short

- Joan Collins

- Linda Evans

- Micky Dolenz

- Seana McKenna

- Sal Mineo

- John Mills

- Donald Sinden

- Leslie Phillips

- Olivia de Havilland

- David Suchet

- Lauren Bacall

- Donald Sutherland

- Doug Henning

- Roy Dotrice

Notable productions

[edit]Productions are listed by the year of their first performance.[12]

- 1988: Spoils of War, The Nerd

- 1989: The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe, Les Misérables

- 1990: Sarafina!, Penn & Teller: The Refrigerator Tour, The Heidi Chronicles

- 1991: Kean, Or Disorder and Genius, Time and the Conways, Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing

- 1992: The Secret Garden, Lost in Yonkers

- 1993: Blood Brothers, The Good Times Are Killing Me, Guys and Dolls, Man of La Mancha, Five Guys Named Moe, Crazy for You

- 1996: The Master Builder, One for the Pot, Three Tall Women, Jane Eyre

- 1997: Death of a Salesman, The Glass Menagerie, Jolson, Rent

- 1998: 2 Pianos 4 Hands, Racing Demon, Fame

- 1999: Proposals, Master Class, Our Town, Art, The Needfire

- 2000: Enigma Variations, Mamma Mia!

- 2006: The Boy Friend, The Innocent Eye Test, Wingfield's Inferno, Legends!, Pippin

- 2007: Orpheus Descending, E-Dentity, Dirty Dancing

- 2009: Stuff Happens

- 2010: Rock of Ages

- 2011: The Secret Garden, Calendar Girls, Wishful Drinking, Private Lives, Hair

- 2012: The Blue Dragon, Backbeat: The Birth of The Beatles, La Cage Aux Folles, Terminus

- 2013: Once

- 2014: Metamorphosis, The Last Confession, Our Country's Good, Arcadia, The Heart of Robin Hood

- 2015: Kinky Boots

- 2016: Come from Away

- 2017: The Audience, Mrs Henderson Presents, North by Northwest, The Lorax

- 2018: Come from Away

- 2019: Dear Evan Hansen, Girl from the North Country, Come from Away

- 2022: Boy Falls From The Sky, 2 Pianos 4 Hands, The Shark is Broken, Fisherman's Friends: The Musical

- 2023: Pressure, Hadestown, Six

- 2024: Come from Away

Gallery

[edit]-

The Royal Alex in September 2016

-

Royal Alexandra Theatre in December 2021

-

The stage of the Royal Alexandra Theatre in July 2011.

-

The Q&A with the cast of Mother and Bear movie premier at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, TIFF 2024.

-

The basement where the bar is located at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, in Toronto, Canada.

-

A stairwell to the basement of the Royal Alexandra Theatre, in Toronto, Canada.

-

The British Coat of Arms in the Royal Alexandra Theatre on the ceiling of the entrance, Toronto, Canada.

-

The entrance ceiling of the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto, Canada.

See also

[edit]- Elgin & Winter Garden Theatre

- Massey Hall

- Princess of Wales Theatre

- Roy Thomson Hall

- Hummingbird Centre

- Bathurst Street Theatre

- Ed Mirvish Theatre

- Royal eponyms in Canada

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Royal Alexandra Theatre". 2019-08-02. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- ^ "Royal Alexandra Theatre National Historic Site of Canada".

- ^ "Honest Ed Gets Royal Alex - "Not Looking for a Profit"". Toronto Daily Star. February 16, 1963. p. 1.

- ^ 260 King Street West, Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties

- ^ Royal Alexandra Theatre, Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada

- ^ Royal Alexandra Theatre, National Register of Historic Places

- ^ Knelman, Martin (May 5, 2016). "Exclusive: Royal Alex to shut this month for $2.5 million facelift and reopen in November". Toronto Star. Toronto. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ "Royal Alex is stretching its legs". Toronto Star. 18 October 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Yeo, Debra (5 December 2016). "Mirvish adds extra Toronto show for Come From Away". Toronto Star. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Come From Away ticket sales set record". Toronto Star. 28 November 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ^ Barnard, Linda (September 8, 2017). "At TIFF premiere, Lady Gaga invites 'an authentic and real look into my life'".

- ^ "Royal Alexandra Theatre Show Archives". Retrieved 18 October 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Brockhouse, Robert (2008-02-07). Royal Alexandra Theatre: a Celebration of 100 Years (1 ed.). Harpercollins. ISBN 978-1-55278-648-2.

- Dombowski, Philip and Janet MacKinnon, eds., Toronto's Landmark Restoration Projects, Bulletin of the Historic Theatres Trust/Société des salles historiques, Montreal, Winter 1994/95

- Haynes, N.J. A History of the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1914–1918 PhD dissertation, Univ. of Colo., Boulder, 1973.

- O'Neill, Mora Dianne Guthrie, A Partial History of the Royal Alexandra Theatre, PhD Dissertation, Graduate faculty of Louisiana State University, 1976

- Westcott, Jamie, Royal Alex: From Past to Present, The Toronto Sun, Special Supplement on the 80th Anniversary of the Royal Alexandra, Oct. 18, 1987