Timeline of the gunpowder age

This is a timeline of the history of gunpowder and related topics such as weapons, warfare, and industrial applications. The timeline covers the history of gunpowder from the first hints of its origin as a Taoist alchemical product in China until its replacement by smokeless powder in the late 19th century (from 1884 to the present day).

Pre-gunpowder formula

Major developments: Earliest stage of gunpowder development. Mentions of gunpowder ingredients and their uses in conjunction with each other.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 142 | China | A Taoist text known as the Cantong qi, or the Book of the Kinship of Three, by Wei Boyang, who lived in the Eastern Han dynasty, mentions a combination of three powders that fly and dance violently.[1][2] | |

| 318 | China | The ingredients of gunpowder are recorded in the Baopuzi, also known as The Master Who Embraces Simplicity, by Taoist philosopher Ge Hong, who lived in the Jin dynasty (266–420). It describes experiments to create gold with heated saltpeter, pine resin, and charcoal among other carbon materials, resulting in a purple powder and arsenic vapours.[3][4] | |

| 492 | China | Tao Hongjing, a Taoist alchemist, notes that saltpeter burns with a purple flame.[5] | |

| 756 | China | The Taoist Mao Kua reports in his Pinglongren (Recognition of the Recumbent Dragon) that by heating saltpeter, the yin of the air can be obtained, which combines with sulphur, carbon, and metals other than gold.[6] |

9th century

Major developments: Earliest definite references to a gunpowder formula and awareness of its danger.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 808 | China | The Taoist priest Qing Xuzi mentions the gunpowder formula in his Taishang Shengzu Jindan Mijue, describing six parts sulfur to six parts saltpeter to one part birthwort herb.[7] | |

| 858 | China | The Taoist text Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe (Classified Essentials of the Mysterious Way of the True Origin of Things) contains a warning on the dangers of gunpowder: "Some have heated together sulfur, realgar (arsenic disulphide), and saltpeter with honey; smoke [and flames] result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house burned down."[7] |

10th century

Major developments: Gunpowder is utilized in Chinese warfare and an assortment of gunpowder weapons appear. Fire arrows utilizing gunpowder as an incendiary appear in the early 900s and possibly rocket arrows as well by the end of the century. The gunpowder slow match is used for igniting flame throwers. The ancestor of firearms, the fire lance, also appears, but its usage in the 10th century is uncertain and no textual evidence for it exists during this period.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 904 | China | Fire arrows utilizing gunpowder are used by Southern Wu troops during the siege of Yuzhang.[8][9] | |

| 919 | China | The gunpowder slow match appears in China (for igniting flamethrowers).[10] | |

| 950 | China | Fire lances appear in China.[11] | |

| 969 | China | Gunpowder propelled fire arrows, rocket arrows, are invented by Yue Yifang and Feng Jisheng.[12] | |

| 975 | China | The state of Wuyue sends a group of soldiers skilled in the use of fire arrows to the Song dynasty, which uses fire arrows and incendiary bombs in the same year to destroy the fleet of Southern Tang.[13] | |

| 994 | China | The Liao dynasty attacks the Song dynasty and lays siege to Zitong with 100,000 troops, but fails due to the defenders' use of fire arrows.[13] | |

| 1000 | China | Tang Fu demonstrates gunpowder pots and caltrops to the Song court and is rewarded.[14] |

-

A flamethrower from the Wujing Zongyao, supposedly used the gunpowder slow match

-

An arrow strapped with gunpowder ready to be shot from a bow. From the Huolongjing

-

A fire arrow from the Wubei Zhi

-

Rocket arrows from the Huolongjing.

-

Depiction of fire arrows known as "divine engine arrows" (shen ji jian 神機箭) from the Wubei Zhi.

11th century

Major developments: The chemical formula for gunpowder is recorded in the Wujing Zongyao by 1044. Bombs appear in the early 11th century. Gunpowder becomes more common in the Song dynasty and production of gunpowder weapons is systematized. The Song court restricts trade of gunpowder ingredients with the Liao and Western Xia dynasties.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1002 | China | Shi Pu demonstrates fireballs utilizing gunpowder to the Song court and blueprints are created for promulgation throughout the realm.[14] | |

| 1044 | China | The chemical formula for gunpowder appears in the military manual Wujing Zongyao, also known as the Complete Essentials for the Military Classics.[16][17] | |

| China | "Thunderclap bombs" are mentioned in the Wujing Zongyao.[18] | ||

| China | A "triple-bed-crossbow" firing fire arrows is mentioned in the Wujing Zongyao.[19] | ||

| 1067 | China | Private trade of gunpowder ingredients is banned in the Song dynasty.[20] | |

| 1075 | Sinosphere | Vietnam's Lý dynasty used fire arrows and against the Song dynasty during the Lý–Song War (1075–1077).[21] | |

| 1076 | China | Trade of gunpowder ingredients with the Liao and Western Xia dynasties is outlawed by the Song court.[14] | |

| 1083 | China | Three hundred thousand fire arrows are produced by the Song court and delivered to two garrisons.[14] |

-

Earliest known written formula for gunpowder, from the Wujing Zongyao of 1044 AD.

-

An expendable bird carrying an incendiary receptacle around its neck. From the Wujing Zongyao.

-

An 'igniter fire ball' and 'barbed fire ball' from the Wujing Zongyao.

-

A thunderclap bomb as depicted in the Wujing Zongyao.

-

Gunpowder pot and caltrops from the Yuan dynasty.

-

Depiction of a' wind-and-dust bomb' (feng chen pao) from the Huolongjing.

12th century

Major developments: Gunpowder fireworks are mentioned. Ships are equipped with trebuchets for hurling bombs. Earliest recorded usage of gunpowder artillery in ship to ship combat, first mention of the fire lance in battle, and the earliest possible depiction of a cannon appears.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1110 | China | The Song army puts on a firework display for the emperor including a spectacle which opened with "a noise like thunder" and explosives that light up the night. Considered by some to be the first mention of gunpowder fireworks.[22] | |

| 1126 | February | China | Jingkang Incident: Thunderclap bomb as well as fire arrows and fire bombs are used by Song troops during the siege of Kaifeng by the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).[23] |

| 1127 | December | China | "Molten metal bombs", suspected to contain gunpowder, are employed by Song troops when the Jin army returns with fire arrows and gunpowder bombs made by captured Song artisans. Kaifeng is taken.[24] |

| 1128 | China | The earliest extant depiction of a cannon appears among the Dazu Rock Carvings, one of which is a human figure holding a gourd shaped hand cannon.[25] | |

| 1129 | China | Gunpowder weapons are applied to naval warfare as Song warships are outfitted with trebuchets and supplies of gunpowder bombs.[26] | |

| 1132 | China | Siege of De'an: Fire lances are used by Song troops.[27][28][29] | |

| China | Gunpowder is referred to specifically for its military applications for the first time and is known as "fire bomb medicine" rather than "fire medicine".[26] | ||

| China | Firecrackers using gunpowder are mentioned for the first time.[30] | ||

| 1159 | China | Fire arrows are employed by a Song fleet in sinking a Jin fleet off the shore of Shandong peninsula.[31] | |

| 1161 | 26–27 November | China | Battle of Caishi: Thunderclap bombs are employed by Song treadmill boats in sinking a Jin fleet on the Yangtze.[31] |

| 1163 | China | Fire lances are attached to war carts, known as "at-your-desire-war-carts", for defending Song mobile trebuchets.[26] |

-

A fire lance from the Huolongjing.

-

A double barreled fire lance from the Huolongjing. Supposedly they fired in succession, and the second one is lit automatically after the first barrel finishes firing.

13th century

Major developments: Bomb shells gain an iron casing. Fire lances are equipped with projectiles and reusable iron barrels. Rockets are used in warfare. "Fire emitting tubes" are produced in the Song dynasty by the mid-13th century and hand cannons are recorded to have been used in battle by the Yuan dynasty in 1287. The earliest extant cannons appear in China. The Mongols spread gunpowder weaponry to Japan, Southeast Asia, and possibly the Middle East as well as Europe. Europe and India both acquire gunpowder by the end of the century, but only in the Middle East are gunpowder weapons mentioned in any detail.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1207 | China | Thunderclap bombs are employed by Song forces in a sneak attack on a Jin camp, killing 2000 men and 800 horses.[18] | |

| 1221 | China | Iron casing bombs are employed by Jin troops in the siege of Qi Prefecture (Hubei).[32] | |

| 1227 | China | The Wuwei Bronze Cannon, excavated in 1980, is dated to the Western Xia (1038–1227) period. It is currently the oldest possible extant cannon, however like the Heilongjiang hand cannon it contains no inscription and dating is based on contextual evidence.[33] | |

| 1230 | China | Co-viative projectiles are added to fire lances.[34] | |

| 1231 | China | "Thunder crash bombs" are employed by Jin troops in destroying a Mongol warship.[35] | |

| 1232 | China | Reusable fire lance barrels made of durable paper are employed by Jin troops during the Mongol siege of Kaifeng.[35] | |

| China | "Flying fire-lances" with re-usable barrels are used in the defense of Bianjing against Mongols. Some interpret these to be rockets.[36] | ||

| 1237 | China | Large bombs requiring several hundred men to hurl using trebuchets are employed by Mongols in the siege of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui).[37] | |

| 1240 | Middle East | The Middle East acquires knowledge of gunpowder.[38] | |

| 1245 | China | Rockets are used during a military exercise conducted by the Song navy.[39] | |

| 1257 | China | Three hundred thirty-three "fire emitting tubes" are produced in a Song arsenal in Jiankang Prefecture (Nanjing, Jiangsu).[40][41] | |

| 1258 | India | In India, gunpowder is used in pyrotechnics.[42] | |

| 1259 | China | The History of Song describes a "fire-emitting lance" employing a pellet wad projectile which occludes the barrel. Some consider this to be the first bullet.[40][41] | |

| China | The city of Qingzhou produces one to two thousand iron cased bomb shells a month and sends them in deliveries of ten to twenty thousand at a time to Xiangyang and Yingzhou.[43] | ||

| 1264 | China | A display of miniature rockets frightens the Song empress.[44] | |

| 1267 | West | In Europe gunpowder in the form of a firecracker is mentioned in textual sources by Roger Bacon, in his Opus Majus.[45][46] | |

| 1272 | China | Battle of Xiangyang: Fire lances are used by a Song riverine relief force to repel boarders.[47] | |

| 1276 | China | Reusable fire lance barrels made of metal are employed by the Song army.[48] | |

| China | Fire lances are used by Song cavalry in combating Mongols.[47] | ||

| 1277 | China | A suicide bombing occurs in China when Song garrisons set off a large bomb, killing themselves.[49][50] | |

| 1280 | China | "Eruptors," cannons firing co-viative projectiles, are employed in the Yuan dynasty.[51] | |

| China | A major accidental explosion occurs in China when a Yuan gunpowder storehouse at Weiyang, Yangzhou catches fire and explodes, killing 100 guards and hurling building materials over 5 km away.[52] | ||

| Middle East | The Middle East acquires fire lances and rockets.[53] Hasan al-Rammah writes, in Arabic, recipes for gunpowder, instructions for the purification of saltpeter, and descriptions of gunpowder incendiaries.[38] He also provides a description and illustration of the world's first torpedo.[54] | ||

| West | Europe acquires the gunpowder formula.[55] | ||

| 1281 | Sinosphere | Bombs are employed by Mongols in the Mongol invasions of Japan.[56] | |

| 1287 | China | Hand cannons are employed by the troops of Yuan Jurchen commander Li Ting in putting down a rebellion by Mongol prince Nayan.[57] | |

| 1288 | China | The Heilongjiang hand cannon is dated to this year based on contextual evidence and its proximity to the rebellion by Mongol prince Nayan, although it contains no inscription.[58][59] | |

| 1293 | Southeast Asia | Mongol troops of Yuan dynasty carried Chinese cannons to Java in 1293.[60] | |

| 1298 | China | The Xanadu Gun, the oldest confirmed extant hand cannon, is dated to this year based on its inscription and contextual evidence.[61] | |

| 1299 | Middle East | Fire lances are used in battles between the Mongols and Muslims[62] | |

| 1300 | India | In India Mongol mercenaries deploy fire arrows during a siege.[63] |

-

The 'phalanx-charging fire-gourd' forgoes the spearhead and relies solely on the force of gunpowder and projectiles. From the Huolongjing.

-

An illustration of a 'flying-cloud thunderclap-eruptor,' a cannon firing thunderclap bombs, from the Huolongjing.

-

A 'poison fog divine smoke eruptor' (du wu shen yan pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Small shells emitting poisonous smoke are fired.

-

Cannon with trunnions, Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

-

Stone cannon balls unearthed in Shangdu, Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)

-

Yuan dynasty bombs, known in Japanese as Tetsuhau (iron bomb), or in Chinese as Zhentianlei (thunder crash bomb), dated to the Mongol invasions of Japan (1271–1284).

14th century

Major developments: Chinese gunpowder weaponry continues to advance with the development of one-piece cast iron cannons, accompanying carriages, and the addition of land mines, naval mines and rocket launchers. Earliest recorded instance of volley fire with gunpowder weaponry, by the Ming dynasty. The rest of the world catches up quickly and most of Eurasia acquires gunpowder weapons by the second half of the 14th century. Cannon development in Europe progresses rapidly and by 1374, cannons in Europe are able to breach a city wall for the first time. Breech loading cannons appear in Europe.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1307 | West | The Armenian monk Hetoum writes about a powerful weapon having been invented in China.[64] | |

| 1325 | China | Bronze "thousand-ball thunder-cannons" on four wheeled carriages appear in the Yuan dynasty.[65] | |

| 1326 | West | In Europe the depiction of a cannon appears.[66][67] | |

| 1330 | West | In Andalusia cannons are mentioned in textual sources.[68] | |

| West | Europe's oldest extant firearm, the Loshult gun, is dated to this year.[69] | ||

| 1331 | Iberia | The Nasrid army besieging Elche makes use of "iron pellets shot with fire."[70] | |

| 1333 | West | Earliest extant cannon arrow projectile is dated to this year. Now kept in the Eltz Castle.[71] | |

| 1338 | West | An organ gun and three pounds of gunpowder are recorded to have been in the possession of a raiding party that sacked Southampton.[66] | |

| 1339 | West | The word "cannon", derived from the Greek kanun and Latin canna, meaning "tube," is used for the first time in Europe.[72] | |

| West | The word "gun" is used to describe a firearm in English for the first time.[72] | ||

| 1340 | China | A "watermelon bomb" containing miniature rockets known as "ground rats" is employed by Liu Bowen against rebels and pirates in Zhejiang.[73] | |

| 1344 | West | Wooden cannons appear in Europe.[74] | |

| 1346 | 26 August | West | Battle of Crécy: Organ guns are used.[75] |

| West | The term "bombard" is used to refer to guns of any kind.[76] | ||

| 1350 | China | Cast iron technology becomes reliable enough to make one-piece iron cannons in China.[77] | |

| China | Flint and wheel mechanisms are employed in igniting land mines and naval mines in China.[78] | ||

| China | In China organ guns appear.[79] | ||

| China | Two wheeled gun carriages appear in China.[80] | ||

| India | India acquires rockets.[81] | ||

| 1352 | Southeast Asia | Cannons are mentioned to have been used by the Ayutthaya Kingdom in their invasion of the Khmer Empire[82] | |

| 1358 | China | Defending garrisons fire cannons en masse at the siege of Shaoxing and defeat a Ming army.[83] | |

| 1360 | Middle East | In the middle east metal-barrel guns start appearing in textual sources.[68] | |

| Southeast Asia | Gunpowder barrels aboard a Khmer ship explode.[82] | ||

| 1363 | 30 August – 4 October | China | Battle of Lake Poyang: Cannons are used in ship combat and a new weapon called the "No Alternative" also appears. It consists of a reed mat bundled together with gunpowder and iron pellets hung on a pole from the foremast of a ship. When an enemy ship is within range, the fuse is lit, and the bundle falls onto the enemy ship spitting iron pellets and burning their men and sails.[84] |

| 1364 | West | Breech loading cannons start appearing in Europe.[85] | |

| 1366 | China | Two thousand four hundred large and small cannons are deployed by the Ming army at the siege of Suzhou.[83] | |

| India | The Vijayanagara Empire acquires firearms.[86] | ||

| 1368 | China | Crouching-tiger cannons are employed by the Ming army.[87] | |

| 1370 | China | Gunpowder is corned to strengthen the explosive power of land mines in the Ming dynasty.[88] | |

| China | Cannon projectiles transition from stone to iron ammunition in the Ming dynasty.[89] | ||

| 1372 | China | Cannons made specifically for naval usage appear in the Ming dynasty.[90] | |

| 1373 | West | The term "hand gun", also known as handgonne, gunnies, vasam scolpi, pot, capita, and testes, appears in European texts for the first time.[91] | |

| 1374 | Sinosphere | Goryeo starts producing gunpowder.[92] | |

| West | Cannons breach a city wall for the first time in Europe.[64] | ||

| 1375 | West | "Basilisk" cannons appear.[93] | |

| West | A 900 kg large-calibre gun is produced in Europe.[94] | ||

| Worldwide | Flash pans are added to hand cannons.[95] | ||

| West | European gunsmiths begin testing barrels for structural integrity, improving quality.[96] | ||

| 1377 | Sinosphere | Goryeo starts producing cannons and rockets.[97][98] | |

| 1380 | China | "Wasp nest" rocket launchers are manufactured for the Ming army.[73] | |

| 24 June | West | Battle of Chioggia: In Europe rockets are used in battle.[99] | |

| West | Europeans develop the means to produce saltpeter for themselves.[74] | ||

| 1382 | West | European sailing ships are equipped with cannons.[100] | |

| 3 May | West | Battle of Beverhoutsveld: The first military conflict in Europe where cannons play a decisive role.[101] | |

| 1388 | China | Ming–Mong Mao War: Volley fire is implemented with cannons by the Ming artillery corps in the anti-insurrection war waged against the Mong Mao.[102] | |

| West | Saltpeter plantations start appearing in Europe.[103] | ||

| 1390 | Southeast Asia | Đại Việt soldiers kill the king of Champa, Che Bong Nga, using hand cannons.[104] | |

| 1396 | West | In Europe mounted knights start employing fire lances.[105] | |

| 1398 | 17 December | India | Delhi Sultanate uses bombs against Tamerlane.[106] |

| 1399 | West | Germany's oldest extant firearm is dated to this year.[107] |

-

A "nest of bees" (yi wo feng 一窩蜂) arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi.

-

A 'divine bone dissolving fire oil bomb' (lan gu huo you shen pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

A bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon" from the Huolongjing.

-

The 'self-tripped trespass land mine' (zi fan pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

Naval mine system known as the 'marine dragon-king' (shui di long wang pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

Oldest known European depiction of a firearm from De Nobilitatibus Sapientii Et Prudentiis Regum by Walter de Milemete (1326).

-

Battle of Nicopolis 1398

15th century

Major developments: Large-calibre artillery weighing several thousand kg are produced in Europe during the early 15th century and spread to the Ottoman Empire. Modifiable two wheeled gun carts known as limbers and caissons appear, greatly improving the mobility of artillery. The matchlock arquebus, the first firearm with a trigger mechanism, appears in Europe by 1475. Rifled barrels also appear in the late 15th century. The term musket is used for the first time in 1499. Rocket launchers are used in battle by the Ming dynasty and the Korean kingdom of Joseon develops a mobile rocket launcher vehicle called the hwacha. Chinese style bombs are used in Japan by 1468 at the latest.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1400 | West | In Europe the gunpowder slow match appears.[108] | |

| China | Li Jinglong uses rocket launchers against the army of the Yongle Emperor.[73] | ||

| West | Springalds are entirely replaced by gunpowder weapons[109] | ||

| 1405 | West | Europe acquires bombs.[51] | |

| 1407 | China | Ironwood wadding is added to Ming cannons, increasing their effectiveness.[110] | |

| 1409 | Sinosphere | Battle carts armed with cannons firing iron fletched darts are produced in Joseon.[111] | |

| 1410 | Sinosphere | Joseon ships are equipped with cannons.[112] | |

| West | "Culverins" are mentioned for the first time.[93] | ||

| West | "Saker" cannons appear.[93] | ||

| 1411 | West | A "serpentine" lever is added to the stocks of hand cannons in Europe to hold matches. The resulting firearm, the hook gun, becomes known as the arquebus.[113] | |

| 1412 | China | Shells are used as ammunition in the Ming dynasty.[114] | |

| 1413 | Sinosphere | Joseon mortars capable of firing 500 meter iron shots and 600 meter stone shots are mentioned.[115] | |

| Southeast Asia | The customs of firing cannons and pole gun is mentioned as part of Javanese marriage ceremony.[116][117]: 245 | ||

| 1415 | Sinosphere | 10,000 guns are deployed throughout Joseon[115] | |

| 1419 | China | During the Lantern Festival, the Ming imperial palace puts on a display of pyrotechnics involving rockets running along wires which light up lanterns, illuminating the palace.[99] | |

| 1420 | West | In Europe war wagons are used as mobile firearm platforms during the Hussite Wars.[31] | |

| 1420 | Sinosphere | Iron shot replaces stone as the standard ammunition in Joseon[115] | |

| 1421 | Southeast Asia | A Chinese pole cannon found in Java is dated from this year, bearing the name of Yongle Emperor.[118][119] | |

| 1425 | West | In Europe gunpowder corning is practiced.[120] | |

| 1429 | China | Mounted infantry carrying hand cannons are employed by the Ming army.[121] | |

| 1431 | West | A 12,000 kg wrought iron large-calibre gun capable of firing 300 kg projectiles, called Dulle Griet, is produced in Europe.[122] | |

| West | European cannon projectiles transition from stone to iron ammunition.[123] | ||

| 1437 | West | In Europe shells are used as ammunition.[124] | |

| West | A master gunner in Europe is forced to make a pilgrimage to Rome after scaring his fellow soldiers, who accused him of satanic devilry, with an astounding rate of fire of three rounds in one day.[125] | ||

| 1447 | Sinosphere | Sejong the Great of Joseon decrees that all fire-squads should carry standardized firearms.[126] | |

| 1450 | West | European walls become lower and thicker in response to cannons.[127] | |

| West | Trunnions appear in Europe.[128] | ||

| 15 April | West | Battle of Formigny: Marks the rapid decline of the English longbow as they prove to be inferior to cannons in both range and rate of fire.[129] | |

| 1451 | Sinosphere | A type of multiple arrow rocket launcher known as the "Munjong Hwacha" is produced in Joseon.[130] | |

| 1453 | West | Modifiable two wheeled gun carts known as limbers appear, greatly improving cannon maneuverability and mobility.[131][128] | |

| 1456 | India | Malwa Sultanate uses cannons as siege weapons to demolish ramparts: In India cannons become widespread.[132][133] | |

| 1460 | 3 August | West | James II of Scotland is killed by one of his own guns, which exploded while he was standing close to it.[96] |

| West | "Mortars" are mentioned for the first time.[93] | ||

| 1464 | Middle East | A 16,800 kg cast bronze large-calibre gun known as the Great Turkish Bombard is created in the Ottoman Empire.[134] | |

| 1468 | Sinosphere | A Chinese "thunderbomb" made of paper and bamboo wrapping two pounds of gunpowder and iron filings is mentioned to have been in use in Japan; Chinese style bombs are used as trebuchet shots until at least 1500[132] | |

| 1470 | West | A shoulder stock is added to hand cannons in Europe.[91] | |

| 1471 | Southeast Asia | Cham–Annamese War: Lê dynasty troops use cannons to blast a breach in Vijaya's fortifications prior to capturing the city[135] | |

| 1472 | India | In India land mines appear; Bahmani Sultanate utilizes them in siege warfare.[136] | |

| 1475 | West | The matchlock mechanism is added to the arquebus, making it the first firearm with a trigger.[137] | |

| 1479 | West | A four layer artillery tower is built at Querfurth in Saxony.[138] | |

| 1480 | West | Guns reach their classic form in Europe.[139] | |

| West | "Falconets" are mentioned for the first time.[140] | ||

| West | "Minion" cannons appear.[140] | ||

| 1486 | West | European oar ships start carrying cannons.[141] | |

| 1488 | West | Henry VII of England's ships, the Regent and Sovereign, are among the first to carry enough cannons to deliver a 'ship killing' blow at a distance.[142] | |

| 1498 | West | Specialized hunting firearms with rifled barrels appear in Europe.[143] | |

| 1499 | 25 August | West | Battle of Zonchio: Breech-loading iron cannons are used in naval warfare.[144] |

| West | The term musket or moschetto is used for the first time in Europe.[91] |

-

Breech loading cannon, 1410.

-

Faule Magd ("Lazy Maid"), a medieval cannon from ca. 1410–1430.

-

Mons Meg, a medieval Bombard (weapon) built in 1449.

-

The bronze Great Turkish Bombard, used by the Ottoman Empire in the siege of Constantinople in 1453.

-

Early arquebuses prior to the matchlock were just hand cannons with a hook

-

A serpentine matchlock mechanism

-

A hwacha assembly and disassembly illustration from the Gukjo Orye Seorye, 1474

16th century

Major developments: Matchlock firearms spread throughout Eurasia, reaching China and Japan by the mid-16th century. The volley fire technique is implemented using matchlock firearms by the Ottomans, Ming dynasty, and Dutch Republic by the end of the century. The arquebus is replaced by its heavier variant called the musket to combat heavily armoured troops. "Musket" becomes the dominant term for all shoulder arms fireweapons until the mid-19th century. The wheellock and flintlock trigger mechanisms are invented. Pistols and revolvers both appear during this period. Ottoman troops attach bayonets to their firearms. Both Europe and China develop handheld breech loading firearms. The star fort spreads across Europe in response to increasing effectiveness of siege artillery. The Ming dynasty uses gunpowder for hydraulic engineering.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1500 | India | India acquires matchlocks.[145] | |

| West | The term "artillery" solidifies as a general term for cannons, their ammunition, support equipment, and operating personnel.[72] | ||

| 1503 | 28 April | West | Battle of Cerignola: Marks the first military conflict where arquebusiers played a decisive role.[146] |

| 1505 | West | The wheellock appears in Europe as an expensive alternative to the matchlock.[91] | |

| 1508 | India | India acquires Portuguese cannons.[147] | |

| West | The earliest extant rifles are dated to this year.[91] | ||

| 1510 | Sinosphere | Japan acquires cannons.[148] | |

| China | Portuguese "Frankish" cannons are used on Guangdong's coastline by Chinese pirates.[149] | ||

| 1515 | West | A man in (Germany) accidentally shoots a prostitute in the chin with a pistol. Considered to be the earliest recorded firearm accident.[150] | |

| 1516 | Southeast Asia | Đại Việt and Lê dynasty produce matchlocks.[151] | |

| 1521 | West | A larger arquebus capable of penetrating plate armor known as the musket appears in Europe.[152] | |

| 1523 | China | The Ming dynasty produces breech-loading swivel guns based on Portuguese designs.[149] | |

| 1526 | 21 April | India | Mughal Emperor Babur use firearms against Sultan Ibrahim Lodi, therefore winning the First Battle of Panipat. |

| 29 August | West | Battle of Mohács: Volley fire is implemented with matchlocks by Ottoman Janissaries.[153] | |

| 1527 | West | "Ordnance" is used to describe artillery for the first time.[154] | |

| 1530 | West | The star fort becomes the dominant type of defensive structure in Italy.[155] | |

| West | Earliest dated "carbine" made in Augsburg.[91] | ||

| 1533 | China | Composite metal cannons are produced in the Ming dynasty.[156][157][158] | |

| 1537 | West | Handheld breech-loading firearms start appearing in Europe.[159] | |

| West | Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia applies mathematical applications to artillery trajectories in his Nova Scientia.[160] | ||

| 1540 | West | Cast iron cannons in Europe become reliable enough to arm sailing ships with two full broadsides.[161] | |

| Southeast Asia | In Southeast Asia matchlocks start seeing widespread use.[162] | ||

| West | Cavalry in Europe start abandoning the lance and adopt the wheellock pistol.[163] | ||

| 1541 | China | Gunpowder is used for hydraulic engineering in the Ming dynasty.[164] | |

| 1543 | Sinosphere | Japan acquires knowledge of matchlocks.[162] | |

| 1544 | 27 January | Sinosphere | In Japan Tanegashima Tokitaka employs matchlocks in the invasion of Yakushima.[165] |

| West | Wooden cannons are used for the last time in Europe.[166] | ||

| West | Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor attempts to standardize gun types.[167] | ||

| 1545 | India | Gujarat experiments with composite metal cannons.[158] | |

| West | Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia invents the gunner's quadrant, an instrument which calculates trajectory.[160] | ||

| 1548 | China | The Ming army starts fielding matchlocks.[168] | |

| 1550 | West | The large arquebus known as the musket becomes obsolete due to lack of armor, but continues as the most widely used term for similar firearms in Europe.[169] | |

| West | The snaphance flintlock mechanism appears in Europe.[170] | ||

| West | The 'flask trail' carriage replaces solid stock trail carriages in Europe.[171] | ||

| 1560 | China | Qi Jiguang publishes his Jixiao Xinshu describing the musket volley fire technique and his experience training the Ming army in its use.[172] | |

| 1561 | China | The Ming dynasty starts producing handheld breech-loading firearms.[173][174] | |

| 1563 | Sinosphere | Joseon starts producing breech-loading swivel guns.[175] | |

| 1568 | West | Calivers are mentioned for the first time in Europe.[91] | |

| 1573 | West | In Europe explosive mines are implemented by Samuel Zimmermann of Augsburg.[176] | |

| 1574 | West | In Europe designs for naval mines are completed.[177] | |

| 1575 | 28 June | Sinosphere | Battle of Nagashino: In Japan Oda Nobunaga's tanegashima troops employ volley fire.[162] |

| West | Trigger guards start appearing on European firearms.[169] | ||

| 1580 | West | Revolvers appear in Europe.[178] | |

| 1594 | 8 December | West | William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg describes the countermarch volley fire technique in a letter to his cousin Maurice, Prince of Orange, and starts training the Dutch army in volley fire.[179] |

| 1598 | China | Ming cavalry experiments with firing a three-barreled matchlock before using it as a shield while they attack with a saber using their other hand.[180] | |

| Middle East | The first mention of a bayonet occurs in the Shenqipu describing a knife attached to an Ottoman musket.[181] | ||

| 1600 | Middle East | Ottoman cavalry starts carrying pistols.[182] | |

| West | The term "howitzer" comes to refer to the weapon.[183] |

-

Matchlock firearms in the 16th century

-

Diagram of a 1594 Dutch musketry volley formation

-

Palmanova star fort in 1593

-

A breech loading matchlock from the Shenqipu

17th century

Major developments: Bayonets spread across Eurasia. A paper cartridge is introduced by Gustavus Adolphus. Rifles are used for war by Denmark. A ship of the line carrying 60 to 120 cannons appears in Europe. Samuel Pepys' diary mentions a machine gun like pistol. The "true" flintlock replaces the snaphance flintlock in Europe by the end of the 17th century. Both China and Japan reject the flintlock and the Mughal Empire only uses it in limited quantities. Gunpowder is used for mining in Europe.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1606 | China | Ming muskets are attached with plug bayonets.[184] | |

| 1607 | Sinosphere | Joseon musketeers are trained in the volley fire technique.[185] | |

| 1611 | West | Paper cartridges are introduced by Gustavus Adolphus.[186] | |

| West | Rifles are used in warfare by Denmark.[91] | ||

| 1613 | Sinosphere | In Japan Date Masamune orders the construction of the Date Maru, a ship built in the style of a Spanish galleon, capable of carrying large cannons.[187] | |

| 1619 | 14–18 April | Sinosphere | Battle of Sarhu: Later Jin cavalry defeats Ming and Joseon musketeers.[188] |

| 1620 | China | Ming foundries start producing Hongyipao.[156] | |

| 1627 | West | Gunpowder is used for mining in Europe.[189] | |

| 1629 | West | Holland experiments with composite metal cannons.[158] | |

| 1632 | China | Ming defensive planners build some star forts but they don't catch on in China.[190] | |

| 1633 | China | Ming dockyards start construction of multidecked broadside sailing ships capable of holding large cannons under the supervision of Zheng Zhilong.[191] | |

| 1635 | China | Telescopes are used for aiming artillery in the Ming dynasty.[192] | |

| 1636 | Sinosphere | The Dutch attempt to trade flintlock firearms with the Japanese but the new firing mechanism doesn't catch on in Japan.[78] | |

| 1637 | Sinosphere | Shimabara Rebellion: In Japan the last major military engagement involving muskets, before firearm suppression policies are enacted, is conducted against an uprising of peasant-farmers and landless samurai.[193] | |

| 1642 | 20 January | China | Li Zicheng's rebels manage to create a two zhang breach in Ming fortifications using cannons.[194] |

| 1643 | 26 July | West | Storming of Bristol: In Europe fire lances are used for the last time.[195] |

| 1650 | West | Ship of the line carrying 60 to 120 cannons in broadside batteries appear in Europe.[196] | |

| 1662 | 3 July | West | Samuel Pepys' diary mentions a mechanic who claimed to be able to make a machine-gun like pistol.[197][198] |

| 1671 | West | European forces attach bayonets to their firearms.[181] | |

| 1680 | West | The snaphance goes out of fashion in favor of the "true" flintlock in Europe.[169] | |

| 1694 | India | India acquires flintlocks; Mughal Empire uses them in limited quantities.[199] |

-

HMS Sovereign of the Seas, 102 guns, 1637.

-

HMS Royal Charles (1673), 100 gun

-

HMS Britannia (1682), 100 guns

-

Plug bayonet from the 1650s

18th century

Major developments: Flintlocks completely displace matchlock firearms in Europe both on land and at sea. Sir William Congreve, 1st Baronet discovers "cylinder powder", gunpowder produced using charcoal in iron cylinders, which is twice as powerful as traditional gunpowder and less likely to spoil. He also invents block trail carriages, the most advanced artillery transport of the time. James Puckle invents a breechloader flintlock capable of firing 63 shots in seven minutes. The Kingdom of Mysore deploys iron cased rockets known as Mysorean rockets.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1702 | West | In Europe telescopes are used to aid in the aiming of artillery.[200] | |

| 1715 | West | Jean Maritz introduces the horizontal drilling technique for casting cannons, increasing their reliability and accuracy while reducing the amount of metal needed for the barrel.[201] | |

| 1718 | West | James Puckle invents the Puckle gun, a breech loading flintlock with a revolving set of chambers capable of firing 63 shots in seven minutes.[198] | |

| 1720 | West | France establishes Europe's first national artillery school.[202] | |

| 1725 | West | Flintlock firearms completely displace matchlocks in Europe.[170] | |

| 1742 | West | Benjamin Robins invents the ballistic pendulum, which provides the first way to accurately measure the velocity of a bullet.[203] | |

| 1750 | Worldwide | Firearms overtake the composite bow in cost, ease of use, range, and rate of fire, making mounted horse archers completely obsolete.[204] | |

| West | A detent is added to flintlocks to prevent the sear from catching in the half-cock notch.[91] | ||

| 1755 | West | Naval guns are outfitted with flintlocks[205] | |

| 1759 | West | "Carronades" appear.[206] | |

| 1770 | West | A roller bearing is added to flintlocks to reduce friction and produce more sparks.[91] | |

| 1780 | West | A waterproof pan is added to flintlocks.[91] | |

| 1783 | West | Sir William Congreve, 1st Baronet improves gunpowder production by constructing dedicated testing ranges, new saltpeter refineries, and special proving houses. He also discovers "cylinder powder", gunpowder produced using charcoal sealed in iron cylinders, which is twice as powerful as traditional gunpowder and less likely to spoil, giving British gunpowder a reputation as best in the world.[207] | |

| 1790 | West | England begins fielding block trail carriages, invented by Sir William Congreve, 1st Baronet, the most advanced artillery transport of the time.[208] | |

| 1799 | 22 April | India | Iron-cased Mysorean rockets are deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company.[209] |

-

Vertical cannon drilling

-

Benjamin Robins describes the ballistic pendulum in the New Principles of Gunnery

-

Flier for Puckle gun of 1718 showing various cylinders for use with round and square bullets.

-

Late 18th century carronade

-

Tipu Sultan soldier using a Mysorean rocket as a flag staff

-

Illustration of Mysorean rockets used by the troops of Tipu Sultan

19th century

Major developments: Sir William Congreve, 2nd Baronet develops the Congreve rockets based on Mysorean rockets and British forces successfully deploy them against Copenhagen. Joshua Shaw invents percussion caps which replace the flintlock trigger mechanism. Claude-Étienne Minié invents the Minié ball, making rifles a viable military firearm, ending the era of smoothbore muskets. Subsequently rifles are deployed in the Crimean War with resounding success. Benjamin Tyler Henry invents the Henry rifle, the first reliable repeating rifle. Richard Jordan Gatling invents the Gatling gun, capable of firing 200 cartridges in a minute. Hiram Maxim invents the Maxim gun, the first single-barreled machine gun. Both China and Europe start using cast iron molds for casting cannons. Alfred Nobel invents dynamite, the first stable explosive stronger than gunpowder. Smokeless powder is invented and replaces the traditional "black powder" in Europe by the end of the century.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1803 | West | England starts producing shrapnel shells.[210] | |

| 1804 | West | Sir William Congreve, 2nd Baronet starts experimenting extensively with rockets based on Mysorean rockets.[209] | |

| 1805 | West | Congreve rockets are produced in Britain.[211] | |

| 1807 | West | British forces successfully deploy 40,000 rockets and ignite devastating fires in Copenhagen[212] | |

| 1812 | West | Jean Samuel Pauly invents a cartridge containing a primer, making it the first self-contained cartridge.[213] | |

| West | Joseph Manton patents the gravitating lock, which prevents muzzle loaders from accidentally firing while the muzzle is held upward.[91] | ||

| 1815 | West | Joshua Shaw invents percussion caps.[214] | |

| 1820 | West | British guns are manufactured with bouched vents.[215] | |

| 1825 | West | The percussion cap mechanism starts replacing flintlocks in Europe.[216] | |

| 1829 | West | Rocket programs in continental Europe fizzle out as poor performance lead to their rejection until the 20th century.[217] | |

| 1830 | West | The percussion cap becomes the most widely accepted firing mechanism in Europe.[214] | |

| 1831 | West | William Bickford invents the safety fuse.[218] | |

| 1835 | West | Casimir Lefaucheux invents the first practical breech loading firearm with a cartridge.[219] | |

| 1836 | West | Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse invents the Dreyse needle gun, a breech loading rifle, increasing the rate of fire to six times that of muzzle loading weapons.[219] | |

| 1837 | West | Edward Alfred Cowper uses gunpowder explosions as railway fog-signals to alert the locomotive crew of danger.[220] | |

| 1841 | China | Wei Yuan recommends the incorporation of flintlock firearms into the Qing army but matchlocks continue to be used.[216] | |

| 1845 | China | Gong Zhenlin invents cast iron molds for the casting of iron cannons.[192] | |

| 1849 | West | Claude-Étienne Minié invents the Minié ball and makes the rifle a viable military firearm, ending the smoothbore musket era.[221] | |

| 1854 | West | Rifles are deployed during the Crimean War with resounding success, proving to be vastly superior to smoothbore muskets.[221] | |

| West | Volcanic Repeating Arms produces a rifle with a self-contained cartridge.[213] | ||

| 1855 | West | The Elswick Ordnance Company starts producing the Armstrong Gun.[157] | |

| West | Edward Boxer uses rockets for throwing life-lines to shipwrecked sailors.[220] | ||

| 1860 | West | Benjamin Tyler Henry invents the Henry rifle, the first reliable repeating rifle.[222] | |

| 1861 | West | Richard Jordan Gatling invents the Gatling gun, capable of firing 200 gunpowder cartridges in a minute.[223] | |

| 1862 | China | The Qing dynasty starts production of percussion caps for rifles.[224] | |

| China | Li Xiucheng of the Taiping army equips his army with foreign rifles.[78] | ||

| 1863 | West | Alfred Nobel invents dynamite, the first stable explosive stronger than gunpowder.[218] | |

| 1864 | China | Li Hongzhang of the Qing dynasty equips his army with 15,000 foreign rifles.[78] | |

| 1873 | West | Winchester Repeating Arms Company introduces the Model 1873 Winchester rifle.[222] | |

| West | In Europe cast iron molds are utilized in casting cannons.[192] | ||

| 1877 | 20 July – 10 December | West | Siege of Plevna: The first time metallic cartridge repeating rifles have a large impact in battle.[222] |

| 1880 | West | Smokeless powder is invented and starts replacing gunpowder, also known as black powder.[225] | |

| 1884 | West | Hiram Maxim invents the Maxim gun, the first single-barreled machine gun.[223] | |

| 1886 | West | A safer and more stable form of smokeless powder is invented in France.[223] | |

| 1890 | West | European countries transition to smokeless powder, which is referred to as "gunpowder", whereas the old mixture is known as "black powder".[226] |

-

The Henry rifle and Winchester rifle

20th century

Major developments: Smokeless powder replaces traditional "black powder" across the globe, ending the gunpowder age.

| Year | Date | Region | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1902 | Worldwide | Smokeless powder is adopted nearly everywhere in the world and "black powder" is relegated to hobbyist usage. So ends the Gunpowder Age.[225] |

See also

- Timeline of the gunpowder age in Japan

- Timeline of the gunpowder age in Korea

- Timeline of the gunpowder age in South Asia

- Timeline of the gunpowder age in Southeast Asia

Citations

- ^ Padmanabhan 2019, p. 59.

- ^ Romane 2020, p. 220.

- ^ Liang 2006, p. 74.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 97.

- ^ Partington 1960, p. 286.

- ^ a b Lorge 2008, p. 32.

- ^ 天佑初,王茂章征安仁义于润州,洎城陷,中十余创,以功迁左先锋都尉。从攻豫章,(郑)璠以所部发机「飞火」,烧龙沙门,率壮士突火先登入城,焦灼被体,以功授检校司徒。(Rough Translation: During the beginning of Tianyou Era (904–907), Zheng Fan followed Wang Maozhang in a campaign against Runzhou, which was guarded by rebel An Renyi. He was severely injured in the process and as the result he was promoted to Junior General of Left Vanguard. At the campaign of Yuchang, he ordered his troops to shoot off a machine to let fire fly and burn the Longsha Gate, after which he led his troops over the fire and entered the city. His body was scorched, for which he was appointed Prime Minister Inspectorate.) Records of Nine Kingdoms ch. 2

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 31.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 85.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Liang 2006.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d Andrade 2016, p. 32.

- ^ "The Genius of China", Robert Temple

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 118–124.

- ^ Ebrey 1999, p. 138.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 154.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 4.

- ^ "The history of gunpowder military using of Vietnam" (in Vietnamese). Thanh Bình. 10 March 2013.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Lu 1988.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 222.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Lorge 2008, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 330.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 230.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 46.

- ^ Lorge 2005, pp. 281–285.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 47.

- ^ a b Kelly 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 511.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- ^ a b Partington 1960, p. 246.

- ^ Khan 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 509.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 25.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 227.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 228.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Partington 1960, pp. 250, 244, 149.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 267.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 259.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan (1987), "Chemical Technology in Arabic Military Treatises", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 500 (1): 153–66 [160], Bibcode:1987NYASA.500..153A, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37200.x, S2CID 84287076

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (19 February 2013). [url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qo4amAg_ygIC&pg=PT41 The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281]. Osprey Publishing. pp 41–42. ISBN 978-1-4728-0045-9. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 32.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 293.

- ^ Reid 1993, p. 220.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 45.

- ^ Roy 2015, p. 115.

- ^ a b Chase 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 319.

- ^ a b Kelly 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 76.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 27 January 2014. ISBN 9781135459321.

- ^ McLachlan 2010, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Kinard 2007, p. ix.

- ^ a b c Needham 1986, p. 514.

- ^ a b Kinard 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Kelly 2004, pp. 19–37.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 144.

- ^ a b c d Needham 1986, p. 466.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 463.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 323.

- ^ Khan 2008, p. 63.

- ^ a b Purton 2010, p. 201.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 66.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 366.

- ^ Khan 2004, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 313.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 110.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 105.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Phillips 2016.

- ^ Seoul National University-College of Humanities-Department of History (30 April 2005). "History of Science in Korea". Vestige of Scientific work in Korea. Seoul National University. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- ^ a b c d Kinard 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 289.

- ^ a b Kinard 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Korean Broadcasting System-News department (30 April 2005). "Science in Korea". Countdown Begins for Launch of South Korea's Space Rocket. Korean Broadcasting System. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 173.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 516.

- ^ Rose 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 157.

- ^ McLachlan 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Tran 2006, p. 75.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 260.

- ^ Purton 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Handgonne Faustbüchse, archived from the original on 14 October 2016, retrieved 17 October 2016

- ^ Willbanks 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Purton 2010, p. 400.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 311.

- ^ Rocket carts of the Ming Dynasty, 14 April 2015, retrieved 18 October 2016

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 425.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 264.

- ^ a b c Purton 2010, p. 390.

- ^ Mayers (1876). "Chinese explorations of the Indian Ocean during the fifteenth century". The China Review. IV: p. 178.

- ^ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- ^ Feldhaus, F.M. (1897). "Eine Chinesische Stangenbüchse von 1421". Zeitschrift für historische Waffenkunde. Vol. 4. Getty Research Institute. Dresden: Verein für historische Waffenkunde. p. 256.

- ^ Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) Vol. 2. Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. p. 178.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 106.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 411.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 164.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 211.

- ^ a b Kelly 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 61.

- ^ "Articles of 1451, Munjongsillok of Annals of Joseon Dynasty (from book 5 to 9, click 문종 for view)". National Institute of Korean History. 1451. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 51.

- ^ a b Purton 2010, p. 392.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 131.

- ^ Schmidtchen (1977b), pp. 226–228

- ^ Purton 2010, p. 202.

- ^ Khan 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Petzal 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Arnold 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Kinard 2007, p. 54.

- ^ Konstam 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Rose 2002, p. 96.

- ^ Curtis 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Grant 2011, p. 88.

- ^ Khan 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 167.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 140.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 430.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Tran 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Arnold 2001, pp. 75–78.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 149.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Arnold 2001, p. 45.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 201.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 334.

- ^ a b c "The Rise and Fall of Distinctive Composite-Metal Cannons Cast During the Ming-Qing Period". Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 457.

- ^ a b Kinard 2007, p. 69.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 169.

- ^ Arnold 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 543.

- ^ Lidin 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 74.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Needham 1986, p. 428.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 429.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 33.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 380.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 202.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 205.

- ^ Pauly 2004.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 145.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 148.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 444.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 96.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 99.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 456.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 183.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 132.

- ^ "Watanoha, Ishinomaki: The San Juan somehow survived" (サン・ファン号「何とか耐えた」 石巻・渡波) Archived 23 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Kahoku Online Network. 18 March 2011.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 187.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 535.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 212.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Needham 1986, p. 412.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 469.

- ^ Swope 2013.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 262.

- ^ Harding 1999, p. 38.

- ^ The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Thursday 3 July 1662. "After dinner, was brought to Sir W. Compton a gun to discharge seven times, the best of all devices that ever I saw, and very serviceable, and not a bawble; for it is much approved of, and many thereof made."

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 410.

- ^ Khan 2004, p. 137.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 413.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 201.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Robins 1742.

- ^ Roy 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 115.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 116.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 252.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 109.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 518.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 126.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 119.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 121.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 134.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 465.

- ^ Kinard 2007, p. 123.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 537.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 15.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 544.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Willbanks 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Chase 2003, p. 202.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 467.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 294.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 232.

References

- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2008), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60391-1

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 0-304-35270-5

- Benton, Captain James G. (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2 ed.). West Point, New York: Thomas Publications. ISBN 1-57747-079-6.

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-1878-0

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), "Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History", Technology and Culture, 49 (3), Aldershot: Ashgate: 785–786, doi:10.1353/tech.0.0051, ISBN 0-7546-5259-9, S2CID 111173101

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82274-2

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-718-0

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79158-8

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 0-904040-13-5

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43519-6

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on 25 March 2004.

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650–1830, UCL Press Limited

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "Explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-03718-6

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–5

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd.

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 8791114128

- Lorge, Peter (2005), Warfare in China to 1600, Routledge

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29 (3): 594–605, doi:10.2307/3105275, JSTOR 3105275

- McLachlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. 5 pt. 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08573-X

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Ghengis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, vol. 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33733-0

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press

- Padmanabhan, Thanu (2019), The Dawn of Science: Glimpses from History for the Curious Mind

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 0-87923-773-2

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-449-6

- Reid, Anthony (1993), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis, New Haven and London: Yale University Press

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Romane, Julian (2020), The First & Second Italian Wars 1494-1504

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000-1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2013), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, 1618–44 (Asian States and Empires), Routledge

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea Ad 612–1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-478-7

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32736-X

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial (2006), ISBN 0-06-093564-2

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.

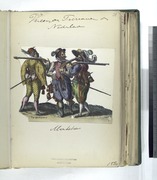

![Earliest known representation of a bomb and fire lance (upper right), Dunhuang, 950 AD.[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/FireLanceAndGrenade10thCenturyDunhuang.jpg/180px-FireLanceAndGrenade10thCenturyDunhuang.jpg)