IEEE 802.11: Difference between revisions

| Line 221: | Line 221: | ||

* {{cite paper |publisher=[[IEEE-SA]] |title=IEEE 802.11y-2008—Amendment 3: 3650–3700 MHz Operation in USA |date=6 November 2008 |doi=10.1109/IEEESTD.2008.4669928 | url=http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.11y-2008.pdf}} |

* {{cite paper |publisher=[[IEEE-SA]] |title=IEEE 802.11y-2008—Amendment 3: 3650–3700 MHz Operation in USA |date=6 November 2008 |doi=10.1109/IEEESTD.2008.4669928 | url=http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.11y-2008.pdf}} |

||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

<ref>[http://www.netspotapp.com Netspot Site Survey, free wireless site survey software for Mac OS X ] </ref> |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

{{Reflist|2}} |

||

Revision as of 22:15, 12 October 2011

IEEE 802.11 is a set of standards for implementing wireless local area network (WLAN) computer communication in the 2.4, 3.6 and 5 GHz frequency bands. They are created and maintained by the IEEE LAN/MAN Standards Committee (IEEE 802). The base version of the standard IEEE 802.11-2007 has had subsequent amendments. These standards provide the basis for wireless network products using the Wi-Fi brand name.

General description

The 802.11 family consists of a series of over-the-air modulation techniques that use the same basic protocol. The most popular are those defined by the 802.11b and 802.11g protocols, which are amendments to the original standard. 802.11-1997 was the first wireless networking standard, but 802.11b was the first widely accepted one, followed by 802.11g and 802.11n. 802.11n is a new multi-streaming modulation technique. Other standards in the family (c–f, h, j) are service amendments and extensions or corrections to the previous specifications.

802.11b and 802.11g use the 2.4 GHz ISM band, operating in the United States under Part 15 of the US Federal Communications Commission Rules and Regulations. Because of this choice of frequency band, 802.11b and g equipment may occasionally suffer interference from microwave ovens, cordless telephones and Bluetooth devices. 802.11b and 802.11g control their interference and susceptibility to interference by using direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) and orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) signaling methods, respectively. 802.11a uses the 5 GHz U-NII band, which, for much of the world, offers at least 23 non-overlapping channels rather than the 2.4 GHz ISM frequency band, where all channels overlap.[1] Better or worse performance with higher or lower frequencies (channels) may be realized, depending on the environment.

The segment of the radio frequency spectrum used by 802.11 varies between countries. In the US, 802.11a and 802.11g devices may be operated without a license, as allowed in Part 15 of the FCC Rules and Regulations. Frequencies used by channels one through six of 802.11b and 802.11g fall within the 2.4 GHz amateur radio band. Licensed amateur radio operators may operate 802.11b/g devices under Part 97 of the FCC Rules and Regulations, allowing increased power output but not commercial content or encryption.[2]

History

802.11 technology has its origins in a 1985 ruling by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission that released the ISM band for unlicensed use.[3]

In 1991 NCR Corporation/AT&T (now Alcatel-Lucent and LSI Corporation) invented the precursor to 802.11 in Nieuwegein, The Netherlands. The inventors initially intended to use the technology for cashier systems; the first wireless products were brought on the market under the name WaveLAN with raw data rates of 1 Mbit/s and 2 Mbit/s.[citation needed]

Vic Hayes, who held the chair of IEEE 802.11 for 10 years and has been called the "father of Wi-Fi" was involved in designing the initial 802.11b and 802.11a standards within the IEEE.[citation needed]

In 1992, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) obtained a patent in Australia for a method of wireless data transfer technology based on the use of Fourier transforms to "unsmear" the signal. In 1996, CSIRO obtained a patent for the same technology in the US.[4] In April 2009, 14 tech companies selling Wi-Fi devices, including Dell, HP, Microsoft, Intel, Nintendo, and Toshiba, agreed to pay CSIRO $250 million for infringements on the CSIRO patents.[5] In 1999, the Wi-Fi Alliance was formed as a trade association to hold the Wi-Fi trademark under which most products are sold.[6]

Protocols

| Frequency range, or type |

PHY | Protocol | Release date[7] |

Frequency | Bandwidth | Stream data rate[8] |

Max. MIMO streams |

Modulation | Approx. range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor | Outdoor | |||||||||||

| (GHz) | (MHz) | (Mbit/s) | ||||||||||

| 1–7 GHz | DSSS[9], |

802.11-1997 | June 1997 | 2.4 | 22 | 1, 2 | — | DSSS, |

20 m (66 ft) | 100 m (330 ft) | ||

| HR/DSSS[9] | 802.11b | September 1999 | 2.4 | 22 | 1, 2, 5.5, 11 | — | CCK, DSSS | 35 m (115 ft) | 140 m (460 ft) | |||

| OFDM | 802.11a | September 1999 | 5 | 5, 10, 20 | 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, 54 (for 20 MHz bandwidth, divide by 2 and 4 for 10 and 5 MHz) |

— | OFDM | 35 m (115 ft) | 120 m (390 ft) | |||

| 802.11j | November 2004 | 4.9, 5.0 [B][10] |

? | ? | ||||||||

| 802.11y | November 2008 | 3.7[C] | ? | 5,000 m (16,000 ft)[C] | ||||||||

| 802.11p | July 2010 | 5.9 | 200 m | 1,000 m (3,300 ft)[11] | ||||||||

| 802.11bd | December 2022 | 5.9, 60 | 500 m | 1,000 m (3,300 ft) | ||||||||

| ERP-OFDM[12] | 802.11g | June 2003 | 2.4 | 38 m (125 ft) | 140 m (460 ft) | |||||||

| HT-OFDM[13] | 802.11n (Wi-Fi 4) |

October 2009 | 2.4, 5 | 20 | Up to 288.8[D] | 4 | MIMO-OFDM (64-QAM) |

70 m (230 ft) | 250 m (820 ft)[14] | |||

| 40 | Up to 600[D] | |||||||||||

| VHT-OFDM[13] | 802.11ac (Wi-Fi 5) |

December 2013 | 5 | 20 | Up to 693[D] | 8 | DL MU-MIMO OFDM (256-QAM) |

35 m (115 ft)[15] | ? | |||

| 40 | Up to 1600[D] | |||||||||||

| 80 | Up to 3467[D] | |||||||||||

| 160 | Up to 6933[D] | |||||||||||

| HE-OFDMA | 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6, Wi-Fi 6E) |

May 2021 | 2.4, 5, 6 | 20 | Up to 1147[E] | 8 | UL/DL MU-MIMO OFDMA (1024-QAM) |

30 m (98 ft) | 120 m (390 ft)[F] | |||

| 40 | Up to 2294[E] | |||||||||||

| 80 | Up to 5.5 Gbit/s[E] | |||||||||||

| 80+80 | Up to 11.0 Gbit/s[E] | |||||||||||

| EHT-OFDMA | 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7) |

Sep 2024 (est.) |

2.4, 5, 6 | 80 | Up to 11.5 Gbit/s[E] | 16 | UL/DL MU-MIMO OFDMA (4096-QAM) |

30 m (98 ft) | 120 m (390 ft)[F] | |||

| 160 (80+80) |

Up to 23 Gbit/s[E] | |||||||||||

| 240 (160+80) |

Up to 35 Gbit/s[E] | |||||||||||

| 320 (160+160) |

Up to 46.1 Gbit/s[E] | |||||||||||

| UHR | 802.11bn (Wi-Fi 8) |

May 2028 (est.) |

2.4, 5, 6, 42, 60, 71 |

320 | Up to 100000 (100 Gbit/s) |

16 | Multi-link MU-MIMO OFDM (8192-QAM) |

? | ? | |||

| WUR[G] | 802.11ba | October 2021 | 2.4, 5 | 4, 20 | 0.0625, 0.25 (62.5 kbit/s, 250 kbit/s) |

— | OOK (multi-carrier OOK) | ? | ? | |||

| mmWave (WiGig) |

DMG[16] | 802.11ad | December 2012 | 60 | 2160 (2.16 GHz) |

Up to 8085[17] (8 Gbit/s) |

— | 3.3 m (11 ft)[18] | ? | |||

| 802.11aj | April 2018 | 60[H] | 1080[19] | Up to 3754 (3.75 Gbit/s) |

— | single carrier, low-power single carrier[A] | ? | ? | ||||

| CMMG | 802.11aj | April 2018 | 45[H] | 540, 1080 |

Up to 15015[20] (15 Gbit/s) |

4[21] | OFDM, single carrier | ? | ? | |||

| EDMG[22] | 802.11ay | July 2021 | 60 | Up to 8640 (8.64 GHz) |

Up to 303336[23] (303 Gbit/s) |

8 | OFDM, single carrier | 10 m (33 ft) | 100 m (328 ft) | |||

| Sub 1 GHz (IoT) | TVHT[24] | 802.11af | February 2014 | 0.054– 0.79 |

6, 7, 8 | Up to 568.9[25] | 4 | MIMO-OFDM | ? | ? | ||

| S1G[24] | 802.11ah | May 2017 | 0.7, 0.8, 0.9 |

1–16 | Up to 8.67[26] (@2 MHz) |

4 | ? | ? | ||||

| Light (Li-Fi) |

LC (VLC/OWC) |

802.11bb | December 2023 (est.) |

800–1000 nm | 20 | Up to 9.6 Gbit/s | — | O-OFDM | ? | ? | ||

(IrDA) |

802.11-1997 | June 1997 | 850–900 nm | ? | 1, 2 | — | ? | ? | ||||

| 802.11 Standard rollups | ||||||||||||

| 802.11-2007 (802.11ma) | March 2007 | 2.4, 5 | Up to 54 | DSSS, OFDM | ||||||||

| 802.11-2012 (802.11mb) | March 2012 | 2.4, 5 | Up to 150[D] | DSSS, OFDM | ||||||||

| 802.11-2016 (802.11mc) | December 2016 | 2.4, 5, 60 | Up to 866.7 or 6757[D] | DSSS, OFDM | ||||||||

| 802.11-2020 (802.11md) | December 2020 | 2.4, 5, 60 | Up to 866.7 or 6757[D] | DSSS, OFDM | ||||||||

| 802.11me | September 2024 (est.) |

2.4, 5, 6, 60 | Up to 9608 or 303336 | DSSS, OFDM | ||||||||

| ||||||||||||

802.11-1997 (802.11 legacy)

The original version of the standard IEEE 802.11 was released in 1997 and clarified in 1999, but is today obsolete. It specified two net bit rates of 1 or 2 megabits per second (Mbit/s), plus forward error correction code. It specified three alternative physical layer technologies: diffuse infrared operating at 1 Mbit/s; frequency-hopping spread spectrum operating at 1 Mbit/s or 2 Mbit/s; and direct-sequence spread spectrum operating at 1 Mbit/s or 2 Mbit/s. The latter two radio technologies used microwave transmission over the Industrial Scientific Medical frequency band at 2.4 GHz. Some earlier WLAN technologies used lower frequencies, such as the U.S. 900 MHz ISM band.

Legacy 802.11 with direct-sequence spread spectrum was rapidly supplanted and popularized by 802.11b.

802.11a

The 802.11a standard uses the same data link layer protocol and frame format as the original standard, but an OFDM based air interface (physical layer). It operates in the 5 GHz band with a maximum net data rate of 54 Mbit/s, plus error correction code, which yields realistic net achievable throughput in the mid-20 Mbit/s [27]

Since the 2.4 GHz band is heavily used to the point of being crowded, using the relatively unused 5 GHz band gives 802.11a a significant advantage. However, this high carrier frequency also brings a disadvantage: the effective overall range of 802.11a is less than that of 802.11b/g. In theory, 802.11a signals are absorbed more readily by walls and other solid objects in their path due to their smaller wavelength and, as a result, cannot penetrate as far as those of 802.11b. In practice, 802.11b typically has a higher range at low speeds (802.11b will reduce speed to 5 Mbit/s or even 1 Mbit/s at low signal strengths). 802.11a too suffers from interference [28], but locally there may be fewer signals to interfere with, resulting in less interference and better throughput.

802.11b

802.11b has a maximum raw data rate of 11 Mbit/s and uses the same media access method defined in the original standard. 802.11b products appeared on the market in early 2000, since 802.11b is a direct extension of the modulation technique defined in the original standard. The dramatic increase in throughput of 802.11b (compared to the original standard) along with simultaneous substantial price reductions led to the rapid acceptance of 802.11b as the definitive wireless LAN technology.

802.11b devices suffer interference from other products operating in the 2.4 GHz band. Devices operating in the 2.4 GHz range include: microwave ovens, Bluetooth devices, baby monitors, and cordless telephones.

802.11g

In June 2003, a third modulation standard was ratified: 802.11g. This works in the 2.4 GHz band (like 802.11b), but uses the same OFDM based transmission scheme as 802.11a. It operates at a maximum physical layer bit rate of 54 Mbit/s exclusive of forward error correction codes, or about 22 Mbit/s average throughput.[29] 802.11g hardware is fully backwards compatible with 802.11b hardware and therefore is encumbered with legacy issues that reduce throughput when compared to 802.11a by ~21%.[citation needed]

The then-proposed 802.11g standard was rapidly adopted by consumers starting in January 2003, well before ratification, due to the desire for higher data rates as well as to reductions in manufacturing costs. By summer 2003, most dual-band 802.11a/b products became dual-band/tri-mode, supporting a and b/g in a single mobile adapter card or access point. Details of making b and g work well together occupied much of the lingering technical process; in an 802.11g network, however, activity of an 802.11b participant will reduce the data rate of the overall 802.11g network.

Like 802.11b, 802.11g devices suffer interference from other products operating in the 2.4 GHz band, for example wireless keyboards.

802.11-2007

In 2003, task group TGma was authorized to "roll up" many of the amendments to the 1999 version of the 802.11 standard. REVma or 802.11ma, as it was called, created a single document that merged 8 amendments (802.11a, b, d, e, g, h, i, j) with the base standard. Upon approval on March 8, 2007, 802.11REVma was renamed to the then-current base standard IEEE 802.11-2007.[30]

802.11n

802.11n is an amendment which improves upon the previous 802.11 standards by adding multiple-input multiple-output antennas (MIMO). 802.11n operates on both the 2.4 GHz and the lesser used 5 GHz bands. The IEEE has approved the amendment and it was published in October 2009.[31][32] Prior to the final ratification, enterprises were already migrating to 802.11n networks based on the Wi-Fi Alliance's certification of products conforming to a 2007 draft of the 802.11n proposal.

Channels and international compatibility

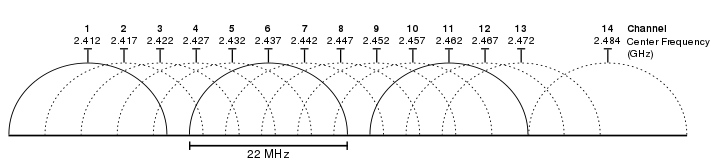

802.11 divides each of the above-described bands into channels, analogously to how radio and TV broadcast bands are sub-divided. For example the 2.4000–2.4835 GHz band is divided into 13 channels each spaced 5 MHz apart, with channel 1 centered on 2.412 GHz and 13 on 2.472 GHz to which Japan adds a 14th channel 12 MHz above channel 13. Since 802.11g OFDM signals use 20 MHz there are only four non-overlapping channels, which are 1, 5, 9 and 13. The previous standard 802.11b was based on DSSS waveforms which used 22 MHz and did not have sharp borders. Due to the way the signal is generated, OFDM waveforms do. Thus only three channels did not overlap. Even now many devices are shipped with channels 1, 6 or 11 as the preset option, slowing the adoption of the newer four channel scheme.

Availability of channels is regulated by country, constrained in part by how each country allocates radio spectrum to various services. At one extreme, Japan permits the use of all 14 channels (with the exclusion of 802.11g/n from channel 14), while other countries like Spain initially allowed only channels 10 and 11, and France only allowed 10, 11, 12 and 13 (now both countries follow the European model of allowing channels 1 through 13[33][34]). Most other European countries are almost as liberal as Japan, disallowing only channel 14, while North America and some Central and South American countries further disallow 12 and 13.

Besides specifying the centre frequency of each channel, 802.11 also specifies (in Clause 17) a spectral mask defining the permitted distribution of power across each channel. The mask requires that the signal be attenuated by at least 30 dB from its peak energy at ±11 MHz from the centre frequency, the sense in which channels are effectively 22 MHz wide. One consequence is that stations can only use every fourth or fifth channel without overlap, typically 1, 6 and 11 in the Americas, and in theory, 1, 5, 9 and 13 in Europe although 1, 6, and 11 is typical there too. Another is that channels 1–13 effectively require the band 2.401–2.483 GHz, the actual allocations being, for example, 2.400–2.4835 GHz in the UK, 2.402–2.4735 GHz in the US, etc.

Since the spectral mask only defines power output restrictions up to ±11 MHz from the center frequency to be attenuated by −50 dBr, it is often assumed that the energy of the channel extends no further than these limits. It is more correct to say that, given the separation between channels 1, 6, and 11, the signal on any channel should be sufficiently attenuated to minimally interfere with a transmitter on any other channel. Due to the near-far problem a transmitter can impact a receiver on a "non-overlapping" channel, but only if it is close to the victim receiver (within a meter) or operating above allowed power levels.

Although the statement that channels 1, 6, and 11 are "non-overlapping" is limited to spacing or product density, the 1–6–11 guideline has merit. If transmitters are closer together than channels 1, 6, and 11 (for example, 1, 4, 7, and 10), overlap between the channels may cause unacceptable degradation of signal quality and throughput.[35] However, overlapping channels may be used under certain circumstances. This way, more channels are available.[36]

Frames

Current 802.11 standards define "frame" types for use in transmission of data as well as management and control of wireless links.

Frames are divided into very specific and standardized sections. Each frame consists of a MAC header, payload and frame check sequence (FCS). Some frames may not have the payload. The first two bytes of the MAC header form a frame control field specifying the form and function of the frame. The frame control field is further subdivided into the following sub-fields:

- Protocol Version: two bits representing the protocol version. Currently used protocol version is zero. Other values are reserved for future use.

- Type: two bits identifying the type of WLAN frame. Control, Data and Management are various frame types defined in IEEE 802.11.

- Sub Type: Four bits providing addition discrimination between frames. Type and Sub type together to identify the exact frame.

- ToDS and FromDS: Each is one bit in size. They indicate whether a data frame is headed for a distributed system. Control and management frames set these values to zero. All the data frames will have one of these bits set. However communication within an IBSS network always set these bits to zero.

- More Fragments: The More Fragments bit is set when a packet is divided into multiple frames for transmission. Every frame except the last frame of a packet will have this bit set.

- Retry: Sometimes frames require retransmission, and for this there is a Retry bit which is set to one when a frame is resent. This aids in the elimination of duplicate frames.

- Power Management: This bit indicates the power management state of the sender after the completion of a frame exchange. Access points are required to manage the connection and will never set the power saver bit.

- More Data: The More Data bit is used to buffer frames received in a distributed system. The access point uses this bit to facilitate stations in power saver mode. It indicates that at least one frame is available and addresses all stations connected.

- WEP: The WEP bit is modified after processing a frame. It is toggled to one after a frame has been decrypted or if no encryption is set it will have already been one.

- Order: This bit is only set when the "strict ordering" delivery method is employed. Frames and fragments are not always sent in order as it causes a transmission performance penalty.

The next two bytes are reserved for the Duration ID field. This field can take one of three forms: Duration, Contention-Free Period (CFP), and Association ID (AID).

An 802.11 frame can have up to four address fields. Each field can carry a MAC address. Address 1 is the receiver, Address 2 is the transmitter, Address 3 is used for filtering purposes by the receiver.

- The Sequence Control field is a two-byte section used for identifying message order as well as eliminating duplicate frames. The first 4 bits are used for the fragmentation number and the last 12 bits are the sequence number.

- An optional two-byte Quality of Service control field which was added with 802.11e.

- The Frame Body field is variable in size, from 0 to 2304 bytes plus any overhead from security encapsulation and contains information from higher layers.

- The Frame Check Sequence (FCS) is the last four bytes in the standard 802.11 frame. Often referred to as the Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC), it allows for integrity check of retrieved frames. As frames are about to be sent the FCS is calculated and appended. When a station receives a frame it can calculate the FCS of the frame and compare it to the one received. If they match, it is assumed that the frame was not distorted during transmission.[37]

Management Frames allow for the maintenance of communication. Some common 802.11 subtypes include:

- Authentication frame: 802.11 authentication begins with the WNIC sending an authentication frame to the access point containing its identity. With an open system authentication the WNIC only sends a single authentication frame and the access point responds with an authentication frame of its own indicating acceptance or rejection. With shared key authentication, after the WNIC sends its initial authentication request it will receive an authentication frame from the access point containing challenge text. The WNIC sends an authentication frame containing the encrypted version of the challenge text to the access point. The access point ensures the text was encrypted with the correct key by decrypting it with its own key. The result of this process determines the WNIC's authentication status.

- Association request frame: sent from a station it enables the access point to allocate resources and synchronize. The frame carries information about the WNIC including supported data rates and the SSID of the network the station wishes to associate with. If the request is accepted, the access point reserves memory and establishes an association ID for the WNIC.

- Association response frame: sent from an access point to a station containing the acceptance or rejection to an association request. If it is an acceptance, the frame will contain information such an association ID and supported data rates.

- Beacon frame: Sent periodically from an access point to announce its presence and provide the SSID, and other parameters for WNICs within range.

- Deauthentication frame: Sent from a station wishing to terminate connection from another station.

- Disassociation frame: Sent from a station wishing to terminate connection. It's an elegant way to allow the access point to relinquish memory allocation and remove the WNIC from the association table.

- Probe request frame: Sent from a station when it requires information from another station.

- Probe response frame: Sent from an access point containing capability information, supported data rates, etc., after receiving a probe request frame.

- Reassociation request frame: A WNIC sends a reassociation request when it drops from range of the currently associated access point and finds another access point with a stronger signal. The new access point coordinates the forwarding of any information that may still be contained in the buffer of the previous access point.

- Reassociation response frame: Sent from an access point containing the acceptance or rejection to a WNIC reassociation request frame. The frame includes information required for association such as the association ID and supported data rates.

Control frames facilitate in the exchange of data frames between stations. Some common 802.11 control frames include:

- Acknowledgement (ACK) frame: After receiving a data frame, the receiving station will send an ACK frame to the sending station if no errors are found. If the sending station doesn't receive an ACK frame within a predetermined period of time, the sending station will resend the frame.

- Request to Send (RTS) frame: The RTS and CTS frames provide an optional collision reduction scheme for access point with hidden stations. A station sends a RTS frame to as the first step in a two-way handshake required before sending data frames.

- Clear to Send (CTS) frame: A station responds to an RTS frame with a CTS frame. It provides clearance for the requesting station to send a data frame. The CTS provides collision control management by including a time value for which all other stations are to hold off transmission while the requesting stations transmits.

Data frames carry packets from web pages, files, etc. within the body.[38]

Standard and amendments

Within the IEEE 802.11 Working Group,[39] the following IEEE Standards Association Standard and Amendments exist:

- IEEE 802.11-1997: The WLAN standard was originally 1 Mbit/s and 2 Mbit/s, 2.4 GHz RF and infrared (IR) standard (1997), all the others listed below are Amendments to this standard, except for Recommended Practices 802.11F and 802.11T.

- IEEE 802.11a: 54 Mbit/s, 5 GHz standard (1999, shipping products in 2001)

- IEEE 802.11b: Enhancements to 802.11 to support 5.5 and 11 Mbit/s (1999)

- IEEE 802.11c: Bridge operation procedures; included in the IEEE 802.1D standard (2001)

- IEEE 802.11d: International (country-to-country) roaming extensions (2001)

- IEEE 802.11e: Enhancements: QoS, including packet bursting (2005)

- IEEE 802.11F: Inter-Access Point Protocol (2003) Withdrawn February 2006

- IEEE 802.11g: 54 Mbit/s, 2.4 GHz standard (backwards compatible with b) (2003)

- IEEE 802.11h: Spectrum Managed 802.11a (5 GHz) for European compatibility (2004)

- IEEE 802.11i: Enhanced security (2004)

- IEEE 802.11j: Extensions for Japan (2004)

- IEEE 802.11-2007: A new release of the standard that includes amendments a, b, d, e, g, h, i & j. (July 2007)

- IEEE 802.11k: Radio resource measurement enhancements (2008)

- IEEE 802.11n: Higher throughput improvements using MIMO (multiple input, multiple output antennas)

- IEEE 802.11p: WAVE—Wireless Access for the Vehicular Environment (such as ambulances and passenger cars) (July 2010)

- IEEE 802.11r: Fast BSS transition (FT) (2008)

- IEEE 802.11s: Mesh Networking, Extended Service Set (ESS) (~ June 2011)

- IEEE 802.11T: Wireless Performance Prediction (WPP)—test methods and metrics Recommendation cancelled

- IEEE 802.11u: Interworking with non-802 networks (for example, cellular) (February 2011)

- IEEE 802.11v: Wireless network management February 2011)

- IEEE 802.11w: Protected Management Frames (September 2009)

- IEEE 802.11y: 3650–3700 MHz Operation in the U.S. (2008)

- IEEE 802.11z: Extensions to Direct Link Setup (DLS) (September 2010)

- IEEE 802.11mb: Maintenance of the standard; will become 802.11-2011 (~ December 2011)

- IEEE 802.11aa: Robust streaming of Audio Video Transport Streams (~ March 2012)

- IEEE 802.11ac: Very High Throughput <6 GHz;[40] potential improvements over 802.11n: better modulation scheme (expected ~10% throughput increase); wider channels (80 or even 160 MHz), multi user MIMO;[41] (~ December 2012)

- IEEE 802.11ad: Very High Throughput 60 GHz (~ Dec 2012)

- IEEE 802.11ae: QoS Management (~ Dec 2011)

- IEEE 802.11af: TV Whitespace (~ Mar 2012)

- IEEE 802.11ah: Sub 1Ghz (~ July 2013)

- IEEE 802.11ai: Fast Initial Link Setup

To reduce confusion, no standard or task group was named 802.11l, 802.11o, 802.11x, 802.11ab, or 802.11ag.

802.11F and 802.11T are recommended practices rather than standards, and are capitalized as such.

802.11m is used for standard maintenance. 802.11ma was completed for 802.11-2007 and 802.11mb is expected to completed for 802.11-2011.

Standard or amendment?

Both the terms "standard" and "amendment" are used when referring to the different variants of IEEE standards.

As far as the IEEE Standards Association is concerned, there is only one current standard; it is denoted by IEEE 802.11 followed by the date that it was published. IEEE 802.11-2007 is the only version currently in publication. The standard is updated by means of amendments. Amendments are created by task groups (TG). Both the task group and their finished document are denoted by 802.11 followed by a non-capitalized letter. For example IEEE 802.11a and IEEE 802.11b. Updating 802.11 is the responsibility of task group m. In order to create a new version, TGm combines the previous version of the standard and all published amendments. TGm also provides clarification and interpretation to industry on published documents. New versions of the IEEE 802.11 were published in 1999 and 2007.

The working title of 802.11-2007 was 802.11-REVma. This denotes a third type of document, a "revision". The complexity of combining 802.11-1999 with 8 amendments made it necessary to revise already agreed upon text. As a result, additional guidelines associated with a revision had to be followed.

Nomenclature

Various terms in 802.11 are used to specify aspects of wireless local-area networking operation, and may be unfamiliar to some readers.

For example, Time Unit (usually abbreviated TU) is used to indicate a unit of time equal to 1024 microseconds. Numerous time constants are defined in terms of TU (rather than the nearly-equal millisecond).

Also the term "Portal" is used to describe an entity that is similar to an 802.1H bridge. A Portal provides access to the WLAN by non-802.11 LAN STAs.

Community networks

With the proliferation of cable modems and DSL, there is an ever-increasing market of people who wish to establish small networks in their homes to share their broadband Internet connection.

Many hotspot or free networks frequently allow anyone within range, including passersby outside, to connect to the Internet. There are also efforts by volunteer groups to establish wireless community networks to provide free wireless connectivity to the public.

Security

In 2001, a group from the University of California, Berkeley presented a paper describing weaknesses in the 802.11 Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) security mechanism defined in the original standard; they were followed by Fluhrer, Mantin, and Shamir's paper titled "Weaknesses in the Key Scheduling Algorithm of RC4". Not long after, Adam Stubblefield and AT&T publicly announced the first verification of the attack. In the attack, they were able to intercept transmissions and gain unauthorized access to wireless networks.

The IEEE set up a dedicated task group to create a replacement security solution, 802.11i (previously this work was handled as part of a broader 802.11e effort to enhance the MAC layer). The Wi-Fi Alliance announced an interim specification called Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) based on a subset of the then current IEEE 802.11i draft. These started to appear in products in mid-2003. IEEE 802.11i (also known as WPA2) itself was ratified in June 2004, and uses government strength encryption in the Advanced Encryption Standard AES, instead of RC4, which was used in WEP. The modern recommended encryption for the home/consumer space is WPA2 (AES Pre-Shared Key) and for the Enterprise space is WPA2 along with a RADIUS authentication server (or another type of authentication server) and a strong authentication method such as EAP-TLS.

In January 2005, IEEE set up yet task group "w" to protect management and broadcast frames, which previously were sent unsecured. Its standard was published in 2009.[42]

Non-standard 802.11 extensions and equipment

Many companies implement wireless networking equipment with non-IEEE standard 802.11 extensions either by implementing proprietary or draft features. These changes may lead to incompatibilities between these extensions.[citation needed]

See also

- Bluetooth, another wireless protocol primarily designed for shorter-range applications.

- Comparison of wireless data standards

- MLME

- OFDM system comparison table

- Ultra-wideband

- Wi-Fi Alliance

- Wi-Fi operating system support

- Wibree

- Wireless Gigabit Alliance, also known as WiGig

References

- "IEEE 802.11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications" (PDF). (2007 revision). IEEE-SA. 12 June 2007. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2007.373646.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "IEEE 802.11k-2008—Amendment 1: Radio Resource Measurement of Wireless LANs" (PDF). IEEE-SA. 12 June 2008. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2008.4544755.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "IEEE 802.11r-2008—Amendment 2: Fast Basic Service Set (BSS) Transition" (PDF). IEEE-SA. 15 July 2008. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2008.4573292.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "IEEE 802.11y-2008—Amendment 3: 3650–3700 MHz Operation in USA" (PDF). IEEE-SA. 6 November 2008. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2008.4669928.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- ^ List of WLAN channels

- ^ "ARRLWeb: Part 97 - Amateur Radio Service". American Radio Relay League. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ "Wi-Fi (wireless networking technology)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ David Sygall. How Australia's top scientist earned millions from Wi-Fi. The Sydney Morning Herald, December 7, 2009.

- ^ Moses, Asher (June 1, 2010). "CSIRO to reap 'lazy billion' from world's biggest tech companies". The Age. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ "Wi-Fi Alliance: Organization". Official industry association web site. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ "Official IEEE 802.11 working group project timelines". January 26, 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

- ^ "Wi-Fi CERTIFIED n: Longer-Range, Faster-Throughput, Multimedia-Grade Wi-Fi Networks" (PDF). Wi-Fi Alliance. September 2009.

- ^ a b Banerji, Sourangsu; Chowdhury, Rahul Singha. "On IEEE 802.11: Wireless LAN Technology". arXiv:1307.2661.

- ^ "The complete family of wireless LAN standards: 802.11 a, b, g, j, n" (PDF).

- ^ The Physical Layer of the IEEE 802.11p WAVE Communication Standard: The Specifications and Challenges (PDF). World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science. 2014.

- ^ IEEE Standard for Information Technology- Telecommunications and Information Exchange Between Systems- Local and Metropolitan Area Networks- Specific Requirements Part Ii: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications. (n.d.). doi:10.1109/ieeestd.2003.94282

- ^ a b "Wi-Fi Capacity Analysis for 802.11ac and 802.11n: Theory & Practice" (PDF).

- ^ Belanger, Phil; Biba, Ken (2007-05-31). "802.11n Delivers Better Range". Wi-Fi Planet. Archived from the original on 2008-11-24.

- ^ "IEEE 802.11ac: What Does it Mean for Test?" (PDF). LitePoint. October 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-16.

- ^ "IEEE Standard for Information Technology". IEEE Std 802.11aj-2018. April 2018. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2018.8345727.

- ^ "802.11ad - WLAN at 60 GHz: A Technology Introduction" (PDF). Rohde & Schwarz GmbH. November 21, 2013. p. 14.

- ^ "Connect802 - 802.11ac Discussion". www.connect802.com.

- ^ "Understanding IEEE 802.11ad Physical Layer and Measurement Challenges" (PDF).

- ^ "802.11aj Press Release".

- ^ "An Overview of China Millimeter-Wave Multiple Gigabit Wireless Local Area Network System". IEICE Transactions on Communications. E101.B (2): 262–276. 2018. doi:10.1587/transcom.2017ISI0004.

- ^ "IEEE 802.11ay: 1st real standard for Broadband Wireless Access (BWA) via mmWave – Technology Blog". techblog.comsoc.org.

- ^ "P802.11 Wireless LANs". IEEE. pp. 2, 3. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved Dec 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "802.11 Alternate PHYs A whitepaper by Ayman Mukaddam" (PDF).

- ^ "TGaf PHY proposal". IEEE P802.11. 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ^ "IEEE 802.11ah: A Long Range 802.11 WLAN at Sub 1 GHz" (PDF). Journal of ICT Standardization. 1 (1): 83–108. July 2013. doi:10.13052/jicts2245-800X.115.

- ^ http://www.oreillynet.com/wireless/2003/08/08/wireless_throughput.html

- ^ Angelakis, V. Papadakis, S. Siris, V.A. Traganitis, Adjacent channel interference in 802.11a is harmful: Testbed validation of a simple quantification model

- ^ Wireless Networking in the Developing World: A practical guide to planning and building low-cost telecommunications infrastructure (PDF) (2nd ed.). Hacker Friendly LLC. 2007. p. 425. page 14

- ^ IEEE 802.11-2007

- ^ http://standards.ieee.org/announcements/ieee802.11n_2009amendment_ratified.html

- ^ "IEEE 802.11n-2009—Amendment 5: Enhancements for Higher Throughput". IEEE-SA. 29 October 2009. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2009.5307322.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); no-break space character in|date=at position 3 (help) - ^ "Cuadro nacional de Atribución de Frecuencias CNAF". Secretaría de Estado de Telecomunicaciones. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "Evolution du régime d'autorisation pour les RLAN" (PDF). French Telecommunications Regulation Authority (ART). Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ "Channel Deployment Issues for 2.4 GHz 802.11 WLANs". Cisco Systems, Inc. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ^ Garcia Villegas, E.; et al. (2007). "CrownCom 2007" (Document). ICST & IEEE.

{{cite document}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help); Unknown parameter|contribution-url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help) - ^ "802.11 Technical Section". Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ^ "Understanding 802.11 Frame Types". Retrieved 2008-12-14.

- ^ "Official IEEE 802.11 working group project timelines". 2009-07-22. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ "IEEE P802.11 - TASK GROUP AC". IEEE. 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fleishman, Glenn (December 7, 2009). "The future of WiFi: gigabit speeds and beyond". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ Jesse Walker, Chair (May 2009). "Status of Project IEEE 802.11 Task Group w: Protected Management Frames". Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ Netspot Site Survey, free wireless site survey software for Mac OS X