Common cold: Difference between revisions

→Pathophysiology: moving |

moved |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

In total over 200 serologically different viral types cause colds.<ref name=Eccles2005/> Coronaviruses are particularly implicated in adult colds. Of over 30 coronaviruses, 3 or 4 cause infections in humans, but they are difficult to grow in the laboratory and their significance is thus less well-understood.<ref name="NIAID2006"/> Due to the many different types of viruses and their tendency for continuous mutation, it is impossible to gain complete immunity to the common cold. |

In total over 200 serologically different viral types cause colds.<ref name=Eccles2005/> Coronaviruses are particularly implicated in adult colds. Of over 30 coronaviruses, 3 or 4 cause infections in humans, but they are difficult to grow in the laboratory and their significance is thus less well-understood.<ref name="NIAID2006"/> Due to the many different types of viruses and their tendency for continuous mutation, it is impossible to gain complete immunity to the common cold. |

||

===Transmission=== |

|||

The common cold virus is typically transmitted from contact with infected saliva or nasal secretions rather than by airborne droplets.<ref name=CE11/> Symptoms are not necessary for viral shedding or transmission, as a percentage of asymptomatic subjects exhibit viruses in nasal swabs.<ref name=gsacc>{{cite web | url=http://dh.sa.gov.au/pehs/Youve-got-what/ygw-common-cold.pdf | title=Common Cold | publisher=Department of Health, Government of South Australia | year=2005 | accessdate=20 June 2007|format=PDF}}</ref> |

|||

===Risk factors=== |

===Risk factors=== |

||

Revision as of 13:50, 23 December 2011

| Common cold | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Family medicine, infectious diseases, otorhinolaryngology |

The common cold (also known as nasopharyngitis, acute viral rhinopharyngitis, acute coryza, or a cold) (Latin: rhinitis acuta catarrhalis) is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory system, caused primarily by rhinoviruses and coronaviruses.[1] Common symptoms include a cough, sore throat, runny nose, and fever. There is no cure for the common cold, but symptoms usually resolve in 7 to 10 days, with some symptoms possibly lasting for up to three weeks.[2]

The common cold is the most frequent infectious disease in humans with the average adult contracting two to three infections a year and the average child contracting between 6 and 12.

Collectively, colds, influenza, and other upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) with similar symptoms are included in the diagnosis of influenza-like illness.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms are cough, sore throat, runny nose, and nasal congestion; sometimes this may be accompanied by conjunctivitis (pink eye), muscle aches, fatigue, headaches, shivering, and loss of appetite. Fever is often present thus creating a symptom picture which overlaps with influenza.[3] The symptoms of influenza however are usually more severe.[4]

Those suffering from colds often report a sensation of chilliness even though the cold is not generally accompanied by fever, and although chills are generally associated with fever, the sensation may not always be caused by actual fever.[3] In one study, 60% of those suffering from a sore throat and upper respiratory tract infection reported headaches,[3] often due to nasal congestion.

Progression

The viral replication begins 2 to 6 hours after initial contact.[5] Symptoms usually begin 2 to 5 days after initial infection but occasionally occur in as little as 10 hours.[6] Symptoms peak 2–3 days after symptom onset, whereas influenza symptom onset is constant and immediate.[3] The symptoms usually resolve spontaneously in 7 to 10 days but some can last for up to three weeks.[2] In children the cough lasts for more than 10 days in 35–40% of cases and continues for more than 25 days in 10%.[7]

The first indication of an upper respiratory virus is often a sore or scratchy throat. Other common symptoms are runny nose, congestion, and sneezing.[8] These are sometimes accompanied by muscle aches, fatigue, malaise, headache, weakness, or loss of appetite.[9] Cough and fever generally indicate influenza rather than an upper respiratory virus with a positive predictive value of around 80%.[3] Symptoms may be more severe in infants and young children, and in these cases it may include fever and hives.[10] Upper respiratory viruses may also be more severe in smokers.[11]

Infectious period

Researchers have studied rhinovirus-caused colds more than other colds. Rhinovirus-caused colds are most infectious during the first three days of symptoms.[12] They become much less infectious after those three days.[12]

Cause

Viruses

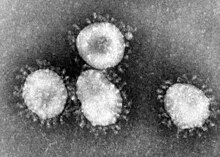

The common cold is a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. The most commonly implicated virus is a rhinovirus (30–50%), a type of picornavirus with 99 known serotypes.[3][13] Others include: coronavirus (10–15%), influenza (5–15%),[3] human parainfluenza viruses, human respiratory syncytial virus, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, and metapneumovirus.[8]

In total over 200 serologically different viral types cause colds.[3] Coronaviruses are particularly implicated in adult colds. Of over 30 coronaviruses, 3 or 4 cause infections in humans, but they are difficult to grow in the laboratory and their significance is thus less well-understood.[8] Due to the many different types of viruses and their tendency for continuous mutation, it is impossible to gain complete immunity to the common cold.

Transmission

The common cold virus is typically transmitted from contact with infected saliva or nasal secretions rather than by airborne droplets.[14] Symptoms are not necessary for viral shedding or transmission, as a percentage of asymptomatic subjects exhibit viruses in nasal swabs.[15]

Risk factors

- Touching eyes, nose, or mouth with contaminated fingers. This behavior increases the likelihood of transferring viruses from the surface of the hands, where they are harmless, into the upper respiratory tract, where they can infect the tissues.[5][8] It has been demonstrated that cold viruses can be spread by touching contaminated objects and surfaces, or by brief contact of hands.[5]

- Spending time in an enclosed area with an infected person or in close contact with an infected person. Common colds are droplet-borne infections, which means that they can be transmitted through breathing in tiny particles that the infected person emits when he or she coughs or sneezes. In one study, the virus was recovered in 1/13 of sneezes and 0/8 coughs generated by adults with natural rhinovirus (cold) infections.[16]

- The role of body cooling as a risk factor the common cold is controversial.[17] It is the most commonly offered folk explanation for the disease, and it has received some experimental evidence. One study showed that exposure to the cold causes the onset of cold symptoms in about 10% of those exposed, and that the subjects experiencing this effect report far more colds overall than those who do not.[18] However, a variety of other studies do not show such an effect.[17]

- A history of smoking extends the duration of illness by about three days.[19]

- Getting fewer than seven hours of sleep per night has been associated with a risk three times higher of developing an infection when exposed to a rhinovirus, compared to those who sleep more than eight hours per night.[20]

- Common colds are seasonal, occurring more frequently during winter outside of tropical zones. Some argue that this is partly due to a change in behaviors such as increased time spent indoors, which puts infected people in close proximity to other people, rather than the exposure to cold temperatures.[8][21]

- Low humidity increases viral transmission rates. One theory is that dry air causes evaporation of water, thus allowing small viral droplets to disperse farther and stay in the air longer.[22]

Pathophysiology

The common cold is a type of pharyngitis (inflammation of the throat). In the common cold, the inflammation is caused by a viral infection in the uppermost part of the throat (the nasopharynx), which runs from behind the nose down to the mouth.

It is generally not possible to identify the virus type through symptoms, although influenza can be distinguished by its sudden onset, fever, and cough.[3]

The major entry point for the virus is normally the nose, but can also be the eyes (in this case drainage into the nasopharynx would occur through the nasolacrimal duct). From there, it is transported to the back of the nose and the adenoid area. The virus then attaches to a receptor, ICAM-1, which is located on the surface of cells of the lining of the nasopharynx. The receptor fits into a docking port on the surface of the virus. Large amounts of virus receptor are present on cells of the adenoid. After attachment to the receptor, virus is taken into the cell, where it starts an infection,[5] and increases ICAM-1 production, which in turn helps the immune response against the virus.[23] Rhinovirus colds do not generally cause damage to the nasal epithelium. Macrophages trigger the production of cytokines, which in combination with mediators cause the symptoms. Cytokines cause the systemic effects. The mediator bradykinin plays a major role in causing the local symptoms such as sore throat and nasal irritation.[3]

The common cold is self-limiting, and the host's immune system effectively deals with the infection. Within a few days, the body's humoral immune response begins producing specific antibodies that can prevent the virus from infecting cells. Additionally, as part of the cell-mediated immune response, leukocytes destroy the virus through phagocytosis and destroy infected cells to prevent further viral replication. In healthy, immunocompetent individuals, the common cold resolves in seven days on average.[5]

Prevention

The best prevention for the common cold is staying away from people who are infected, and places where infected individuals have been.

Regular hand washing is recommended to reduce transmission of cold viruses and other pathogens via direct contact.[24] Virus can be recovered from the hands of ∼40% of adults with rhinovirus colds, and the quantity of virus recovered from the hands is also generally greater than that recovered in coughs and sneezes.[16] Washing of the hands reduces virus count on the skin.[16]

- Hand washing with plain soap and water is recommended. The mechanical action of hand rubbing with plain soap, rinsing, and drying physically removes the virus particles from the hands.[25]

- Alcohol-based hand sanitizers kill viruses, but are not as demonstrably effective in preventing respiratory illness as they are in preventing gastrointestinal illness.[26][27] A 2001 study found that use of an alcohol-free instant hand sanitizer reduced elementary school absences related to respiratory illnesses by 50%.[28]

- Because the common cold is caused by a virus instead of a bacterium, anti-bacterial soaps are no better than regular soap for removing the virus from skin or other surfaces.[25][29]

- Aqueous iodine has been found to reliably eliminate the cold virus on human skin; however, iodine is not acceptable for general use as a virucidal hand treatment because it discolors and dries the skin.[16]

Randomized controlled trials have shown that hand washing using different combinations of cleaning agents resulted in a reduction in the incidence of rhinovirus infections.[30] In two studies at day care facilities, increased handwashing of caregivers reduced the incidence of colds in children by up to 20%.[31][32] However, scheduled handwashing at an elementary school has been shown to reduce the incidence of all communicable illnesses and gastrointestinal illnesses in particular, but was not shown to prevent respiratory ailments.[33]

Cleaning contaminated surfaces such as coffee cup handles with a mixed alcohol/phenol disinfectant has been shown to almost halve the chance of transmission via direct contact.[34]

Efforts to develop a vaccine against the common cold have been unsuccessful. Common colds are produced by a large variety of rapidly mutating viruses; successful creation of a broadly effective vaccine is highly improbable.[35]

While it creates a better environment for the virus, cold weather itself does not directly cause colds[36] and neither is there evidence supporting the idea that cold weather weakens the cells involved in the immune response.[37][verification needed]

Management

There are currently no medications or herbal remedies which have been conclusively demonstrated to shorten the duration of infection in all people with cold symptoms.[38] Treatment comprises symptomatic support usually via analgesics for fever, headache, sore muscles, and sore throat.

Symptomatic

Treatments that help alleviate symptoms include simple analgesics and antipyretics such as ibuprofen[39] and acetaminophen / paracetamol.[40] Evidence does not show that cough medicine is any more effective than simple analgesics[41] and is not recommended for use in children due to a lack of evidence supporting its effectiveness and the potential for harm.[42][43]

Symptoms of a runny nose can be reduced by a first generation antihistamine; however, it can cause drowsiness and other side effects.[44] Other decongestants such as pseudoephedrine are effective in adults but there is insufficient evidence to support their use in children.[45] Anticholinergics such as Ipratropium nasal spray can reduce the symptoms of runny nose with less side effects.[46] One study has found chest vapor rub to be effective at providing some symptomatic relief of nocturnal cough, congestion, and sleep difficulty.[47]

Getting plenty of rest, drinking fluids to maintain hydration, and gargling with warm salt water, are reasonable conservative measures.[8] Due to lack of studies, it is not currently known whether increased fluid intake improves symptoms or shortens respiratory illness[48] and a similar lack of data exists for the use of heated humidified air.[49] Saline nasal drops may help alleviate nasal congestion.[50]

Antibiotics and antivirals

Antibiotics have no effect against viral infections and thus have no effect against the viruses that cause the common cold[51] and due to their side effects cause overall harm.[51] There are no approved antiviral drugs for the common cold even though some preliminary research has shown benefit.[52]

Alternative treatments

While many alternative treatments are used there is insufficient scientific evidence to support the use of most.[11][53] Honey may be a more effective treatment in decreasing cough and improving sleep in children than no treatment or dextromethorphan.[54] However, honey should not be given to a child younger than one year old because of the risk of infant botulism.[55] The benefits versus risk of nasal irrigation are currently unclear and therefore it is not recommended.[56]

Zinc may inhibit rhinovirus replication and reduce inflammation. Trials have found that zinc supplements can somewhat reduce the severity and duration of common cold symptoms when taken by otherwise healthy adults within 24 hours of onset of symptoms.[57][58]

Vitamin C's effect on the common cold has been extensively researched. It has not been shown effective in prevention or treatment of the common cold, except in limited circumstances (specifically, individuals exercising vigorously in cold environments).[59][60] Routine vitamin C supplementation does not reduce the incidence or severity of the common cold in the general population, though it may reduce the duration of illness.[59][61][62]

Evidence about the usefulness of echinacea supplements, a popular herbal remedy, is contradictory.[63][64] Well-conducted research studies tend to have negative results at a much higher rate than poorly conducted studies.[65][66] Different types of echinacea supplements may vary in their effectiveness. Generally, those studies that show supportive results indicate that echinacea might reduce the likelihood of developing cold symptoms upon inoculation with a virus by about half.[67]

Prognosis

The common cold is generally mild and self-limiting[68] with most symptoms generally improving in a week.[14]

Epidemiology

The common cold is the most common infectious diseases among adults, who have two to three annually.[14] Children may have six to ten colds a year (and up to 12 colds a year for school children).[8][69] In the United States, the incidence of colds is higher in the fall (autumn) and winter, with most infections occurring between September and April. The seasonality may be due to the start of the school year, or due to people spending more time indoors (thus in closer proximity with each other) increasing the chance of transmission of the virus.[8]

History

The name "common cold" came into use in the 16th century, due to the similarity between its symptoms and those of exposure to cold weather.[70] Norman Moore relates in his history of the Study of Medicine that James I continually suffered from nasal colds, which were then thought to be caused by polypi, sinus trouble, or autotoxaemia.[71]

In the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin considered the causes and prevention of the common cold. After several years of research he concluded: "People often catch cold from one another when shut up together in small close rooms, coaches, etc. and when sitting near and conversing so as to breathe in each other's transpiration." Although viruses had not yet been discovered, Franklin hypothesized that the common cold was passed between people through the air. He recommended exercise, bathing, and moderation in food and drink consumption to avoid the common cold.[72] Franklin's theory on the transmission of the cold was confirmed some 150 years later.[73]

Common Cold Unit

In the United Kingdom, the Common Cold Unit was set up by the Medical Research Council in 1946. The unit worked with volunteers who were infected with various viruses.[74] The rhinovirus was discovered there.[75] In the late 1950s, researchers were able to grow one of these cold viruses in a tissue culture, as it would not grow in fertilized chicken eggs, the method used for many other viruses. In the 1970s, the CCU demonstrated that treatment with interferon during the incubation phase of rhinovirus infection protects somewhat against the disease,[76] but no practical treatment could be developed. The unit was closed in 1989, two years after it completed research of zinc gluconate lozenges in the prophylaxis and treatment of rhinovirus colds, the only successful treatment in the history of the unit.[77]

Social and cultural

Economics

In the United States, the common cold leads to 75 to 100 million physician visits annually at a conservative cost estimate of $7.7 billion per year. Americans spend $2.9 billion on over-the-counter drugs and another $400 million on prescription medicines for symptomatic relief.[79]

More than one-third of patients who saw a doctor received an antibiotic prescription, which has implications for antibiotic resistance from overuse of such drugs.[79]

An estimated 22 to 189 million school days are missed annually due to a cold. As a result, parents missed 126 million workdays to stay home to care for their children. When added to the 150 million workdays missed by employees suffering from a cold, the total economic impact of cold-related work loss exceeds $20 billion per year.[8][79] This accounts for 40% of time lost from work.[80]

Legal

Canada in 2009 restricted the use of over-the-counter cough and cold medication in children 6 years and under due to concerns regarding risks and unproven benefits.[43]

Cold weather

The traditional folk theory is that a cold can be "caught" by prolonged exposure to cold weather such as rain or winter conditions, which is where the disease got its name.[81] Common colds are seasonal in temperate latitudes, with more occurring during winter. The experimental evidence for this effect is uneven: many experiments have failed to produce evidence that short-term exposure to cold weather or direct chilling increases susceptibility to infection, implying that the seasonal variation is instead due to a change in behaviors such as increased time spent indoors at close proximity to others.[8][21] However, other experiments do find such an effect for both body chilling and cold air exposure, and a number of mechanisms by which lower temperatures could compromise the immune system have been suggested,[17] while other experiments have shown that exposure to cold temperatures may instead stimulate the immune system.[82][83]

Research

ViroPharma and Schering-Plough are developing an antiviral drug, pleconaril, that targets picornaviruses, the viruses that cause the majority of common colds. Pleconaril has been shown to be effective in an oral form.[84][85] Schering-Plough is developing an intra-nasal formulation that may have fewer adverse effects.[86]

Researchers from University of Maryland, College Park and University of Wisconsin–Madison have mapped the genome for all known virus strains that cause the common cold.[86]

References

- ^ "common cold" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b Heikkinen T, Järvinen A (2003). "The common cold". Lancet. 361 (9351): 51–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. PMID 12517470.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eccles R (2005). "Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza". Lancet Infect Dis. 5 (11): 718–25. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X. PMID 16253889.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nordenberg, Tamar (1999). "Colds and Flu: Time Only Sure Cure". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Gwaltney, JM, Hayden, FG (2006). "Understanding Colds". Retrieved 3 July 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "coldorg" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Patsy Hamilton. "Facts about the Common Cold Incubation Period". Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ Goldsobel AB, Chipps BE (2010). "Cough in the pediatric population". J. Pediatr. 156 (3): 352–358.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.004. PMID 20176183.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Common Cold". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- ^ "Common Cold Centre". Cardiff University. 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ "Colds in children". Canadian Pediatric Society. 2005. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "A Survival Guide for Preventing and Treating Influenza and the Common Cold". American Lung Association. 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "ALA2005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Gwaltney JM Jr, Halstead SB. (Document)Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). Invited letter in "Questions and answers". Journal of the American Medical Association. 278 (3): 256–257. 16 July 1997. Retrieved 16 September 2011. - ^ Palmenberg, A. C.; Spiro, D; Kuzmickas, R; Wang, S; Djikeng, A; Rathe, JA; Fraser-Liggett, CM; Liggett, SB (2009). "Sequencing and Analyses of All Known Human Rhinovirus Genomes Reveals Structure and Evolution". Science. 324 (5923): 55–9. doi:10.1126/science.1165557. PMID 19213880.

- ^ a b c Arroll, B (2011 Mar 16). "Common cold". Clinical evidence. 2011. PMID 21406124.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Common Cold" (PDF). Department of Health, Government of South Australia. 2005. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d Turner RB, Hendley JO (2005). "Virucidal hand treatments for prevention of rhinovirus infection". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56 (5): 805–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dki329. PMID 16159927.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Mourtzoukou, E.G.Falagas, M.E. "Exposure to cold and respiratory tract infections". The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Volume 11, Number 9, September 2007 , pp. 938-943(6).

- ^ Johnson, C, Eccles R. "Acute cooling of the feet and the onset of common cold symptoms." Fam Pract. 2005 Dec;22(6):608-13. Epub 2005 Nov 14.

- ^ Aronson MD, Weiss ST, Ben RL, Komaroff AL (1982). "Association between cigarette smoking and acute respiratory tract illness in young adults". JAMA. 248 (2): 181–3. doi:10.1001/jama.248.2.181. PMID 7087108.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Alper CM, Janicki-Deverts D, Turner RB (2009). "Sleep Habits and Susceptibility to the Common Cold". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (1): 62–7. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.505. PMC 2629403. PMID 19139325.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Eccles R (2002). "Acute cooling of the body surface and the common cold". Rhinology. 40 (3): 109–14. PMID 12357708.

- ^ "Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality". Science News. Retrieved Jan21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Winther B; Arruda E; Witek TJ; et al. (2002). "Expression of ICAM-1 in nasal epithelium and levels of soluble ICAM-1 in nasal lavage fluid during human experimental rhinovirus infection". Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 128 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1001/archotol.128.2.131. PMID 11843719.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Boyce JM, Pittet D (2002). "Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America" (PDF). MMWR Recomm Rep. 51 (RR–16): 1–45, quiz CE1–4. PMID 12418624.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Staying healthy is in your hands - Public Health Agency Canada". 17 April 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- ^ Sandora TJ; Taveras EM; Shih MC; et al. (2005). "A randomized, controlled trial of a multifaceted intervention including alcohol-based hand sanitizer and hand-hygiene education to reduce illness transmission in the home". Pediatrics. 116 (3): 587–94. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0199. PMID 16140697.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sandora TJ, Shih MC, Goldmann DA (2008). "Reducing absenteeism from gastrointestinal and respiratory illness in elementary school students: a randomized, controlled trial of an infection-control intervention". Pediatrics. 121 (6): e1555–62. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2597. PMID 18519460.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Catherine G. White; Fay S. Shinder; Arnold L. Shinder (2001). "Reduction of Illness Absenteeism in Elementary Schools Using an Alcohol-free Instant Hand Sanitizer". The Journal of School Nursing. 17 (5): 248–265. doi:10.1177/10598405010170050401.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=3(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Larson EL, Lin SX, Gomez-Pichardo C, Della-Latta P (2004). "Effect of Antibacterial Home Cleaning and Handwashing Products on Infectious Disease Symptoms: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 140 (5): 321–9. PMC 2082058. PMID 14996673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jefferson T; Del Mar C; Dooley L; et al. (2009). "Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review". BMJ. 339: b3675. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3675. PMC 2749164. PMID 19773323.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Carabin H, Gyorkos TW, Soto JC, Joseph L, Payment P, Collet JP (1999). "Effectiveness of a training program in reducing infections in toddlers attending day care centers". Epidemiology. 10 (3): 219–27. doi:10.1097/00001648-199905000-00005. PMID 10230828.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ladegaard MB, Stage V (1999). "[Hand-hygiene and sickness among small children attending day care centers. An intervention study]". Ugeskr. Laeg. (in Danish). 161 (31): 4396–400. PMID 10487104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Master D, Hess Longe SH, Dickson H (1997). "Scheduled hand washing in an elementary school population". Fam Med. 29 (5): 336–9. PMID 9165286.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gwaltney JM, Hendley JO (1982). "Transmission of experimental rhinovirus infection by contaminated surfaces". Am. J. Epidemiol. 116 (5): 828–33. PMID 6293304.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lawrence DM (May 2009). "Gene studies shed light on rhinovirus diversity". Lancet Infect Dis. 9 (5): 278. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70123-9.

- ^ Davidson, Tish, and Teresa G. Odle. "Common Cold." The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, Vol. 2. Detroit: Gale, 2006. pp. 955-959. Retrieved 30 January 2011 from Health & Wellness eBooks database.

- ^ Wexler, Barbara. "Common Cold." The Gale Encyclopedia of Nursing and Allied Health, Vol. 1. Ed. Jacqueline L. Longe. Detroit: Gale, 2006. pp. 613-617. Retrieved 30 January 2011 from Health & Wellness eBooks database.

- ^ "Common Cold: Treatments and Drugs". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ Kim SY, Chang YJ, Cho HM, Hwang YW, Moon YS (2009). Kim, Soo Young (ed.). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006362.pub2. PMID 19588387.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eccles R (2006). "Efficacy and safety of over-the-counter analgesics in the treatment of common cold and flu". Journal of Climical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 31 (4): 309–319. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00754.x. PMID 16882099.

- ^ Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T (2008). Smith, Susan M (ed.). "Over-the-counter medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001831. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub3. PMID 18253996.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "UpToDate Inc".

- ^ a b Shefrin AE, Goldman RD (2009). "Use of over-the-counter cough and cold medications in children". Can Fam Physician. 55 (11): 1081–3. PMC 2776795. PMID 19910592.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gwaltney J.M. Jr., Druce H.M. (1997). "Efficacy of brompheniramine maleate for the treatment of rhinovirus colds". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 25 (5): 1188–1194. doi:10.1086/516105. PMID 9402380.

- ^ Taverner D, Latte J (2007). Latte, G. Jenny (ed.). "Nasal decongestants for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001953. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001953.pub3. PMID 17253470.

- ^ Hayden F.G., Diamond L., Wood P.B., Korts D.C., Wecker M.T. (1996). "Effectiveness and safety of intranasal ipratropium bromide in common colds. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 125 (2): 89–97. PMID 8678385.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul IM, Beiler JS, King TS, Clapp ER, Vallati J, Berlin CM (2010). "Vapor rub, petrolatum, and no treatment for children with nocturnal cough and cold symptoms". Pediatrics. 126 (6): 1092–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1601. PMID 21059712.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Guppy MP, Mickan SM, Del Mar CB (2005). Guppy, Michelle PB (ed.). "Advising patients to increase fluid intake for treating acute respiratory infections". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004419. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004419.pub2. PMID 16235362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singh M; Singh, Meenu (2006). Singh, Meenu (ed.). "Heated, humidified air for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3: CD001728. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001728.pub3. PMID 16855975.

- ^ "Common Cold". PDRHealth. Thomson Healthcare. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- ^ a b Arroll B, Kenealy T (2005). Arroll, Bruce (ed.). "Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD000247. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000247.pub2. PMID 16034850.

- ^ Gwaltney JM, Winther B, Patrie JT, Hendley JO (2002). "Combined antiviral-antimediator treatment for the common cold". J. Infect. Dis. 186 (2): 147–54. doi:10.1086/341455. PMID 12134249.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simasek M, Blandino DA (2007). "Treatment of the common cold". Am Fam Physician. 75 (4): 515–20. PMID 17323712.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Honey A Better Option For Childhood Cough Than Over The Counter Medications". 2007-12-04. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- ^ "Infant botulism: How can it be prevented?". 2010-05-15. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ^ Kassel, JC (2010-03-17). King, David (ed.). "Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD006821. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub2. PMID 20238351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Zinc and Health : The Common Cold". Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ Singh M, Das RR. (2011). Singh, Meenu (ed.). "Zinc for the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001364. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub3. PMID 21328251.

Related news article:

* "Zinc can be an 'effective treatment' for common colds". Cochrane Systematic Review (reported in media). 16 February 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2011. - ^ a b Hemilä, Harri; Chalker, Elizabeth; Douglas, Bob; Hemilä, Harri (2007). Hemilä, Harri (ed.). "Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (3): CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub3. PMID 17636648.

- ^ Heiner, Kathryn A; Hart, Ann Marie; Martin, Linda Gore; Rubio-Wallace, Sherrie (2009). "Examining the evidence for the use of vitamin C in the prophylaxis and treatment of the common cold". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 21 (5): 295–300. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00409.x. PMID 19432914.

- ^ Audera, C (2001). "Mega-dose vitamin C in treatment of the common cold: a randomised controlled trial". Medical Journal of Australia. 389: 175.

- ^ Sasazuki, S; Sasaki, S; Tsubono, Y; Okubo, S; Hayashi, M; Tsugane, S (2005). "Effect of vitamin C on common cold: randomized controlled trial". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 60 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602261. PMID 16118650.

- ^ Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K, Bauer R, Melchart D (2006). Linde, Klaus (ed.). "Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2. PMID 16437427.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sachin A Shah,Stephen Sander ,C Michael White, Mike Rinaldi, Craig I Coleman (2007). "Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 7 (7): 473–480. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70160-3. PMID 17597571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caruso TJ, Gwaltney JM (2005). "Treatment of the common cold with echinacea: a structured review". Clin. Infect. Dis. 40 (6): 807–10. doi:10.1086/428061. PMID 15736012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barrett B; Brown R; Rakel D; et al. (2010). "Echinacea for treating the common cold: A randomized controlled trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 153 (12): 769–77. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00003. PMC 3056276. PMID 21173411.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Funded by the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. - ^ Schoop R, Klein P, Suter A, Johnston SL (2006). "Echinacea in the prevention of induced rhinovirus colds: a meta-analysis". Clin Ther. 28 (2): 174–83. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.02.001. PMID 16678640.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Upper Respiratory Tract Infection at eMedicine

- ^ Simasek M, Blandino DA (2007). "Treatment of the common cold". American Family Physician. 75 (4): 515–20. PMID 17323712.

- ^ "Cold". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ Wylie, A, (1927). "Rhinology and laryngology in literature and Folk-Lore". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 42 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1017/S0022215100029959.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Scientist and Inventor: Benjamin Franklin: In His Own Words... (AmericanTreasures of the Library of Congress)". Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ Andrewes CH, Lovelock JE, Sommerville T (1951). "An experiment on the transmission of colds". Lancet. 1 (1): 25–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(51)93497-6. PMID 14795755.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reto U. Schneider (2004). Das Buch der verrückten Experimente (Broschiert). München: Goldmann. ISBN 344215393X.

- ^ Tyrrell DA (1988). "Hot news on the common cold". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42: 35–47. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.000343. PMID 2849371.

- ^ Tyrrell DA (1987). "Interferons and their clinical value". Rev. Infect. Dis. 9 (2): 243–9. doi:10.1093/clinids/9.2.243. PMID 2438740.

- ^ Al-Nakib, W; Higgins, PG; Barrow, I; Batstone, G; Tyrrell, DA (1987). "Prophylaxis and treatment of rhinovirus colds with zinc gluconate lozenges". J Antimicrob Chemother. 20 (6): 893–901. doi:10.1093/jac/20.6.893. PMID 3440773.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Cost of the Common Cold and Influenza". Imperial War Museum: Posters of Conflict. vads.

- ^ a b c Fendrick AM, Monto AS, Nightengale B, Sarnes M (2003). "The economic burden of non-influenza-related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (4): 487–94. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.4.487. PMID 12588210.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirkpatrick GL (1996). "The common cold". Prim. Care. 23 (4): 657–75. doi:10.1016/S0095-4543(05)70355-9. PMID 8890137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zuger, Abigail (4 March 2003). "'You'll Catch Your Death!' An Old Wives' Tale? Well..." The New York Times.

- ^ Brenner IK; Castellani JW; Gabaree C; et al. (1999). "Immune changes in humans during cold exposure: effects of prior heating and exercise". J. Appl. Physiol. 87 (2): 699–710. PMID 10444630.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Melone, Linda (2009-02-20). "Can the Cold Give You a Cold? - Cold and Flu Center". EverydayHealth.com. Retrieved 2011-09-14.

- ^ Pevear, Daniel C.; T; S; G (1 September 1999). "Activity of Pleconaril against Enteroviruses". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 43 (9): 2109–2115. PMC 89431. PMID 10471549.

- ^ McConnell, J. (2 October 1999). "Enteroviruses succumb to new drug". The Lancet. 354 (9185): 1185. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75393-9.

- ^ a b "Effects of Pleconaril Nasal Spray on Common Cold Symptoms and Asthma Exacerbations Following Rhinovirus Exposure (Study P04295AM2)". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "CTgov" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

External links

- Cold and flu symptom checker (NHS Direct - UK Only)

- Summer Cold (Common Cold Centre, Cardiff University)