Carmine Infantino: Difference between revisions

DoctorSivana (talk | contribs) m →DC Comics editorial director: fixed punctuation |

DoctorSivana (talk | contribs) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

Infantino and writer [[Len Wein]] co-created the "[[Human Target]]" feature in ''[[Action Comics]]'' #419 (December 1972).<ref>McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 153: "Starting as a back-up feature in the pages of ''Action Comics'', scribe Len Wein and artist Carmine Infantino introduced Christopher Chance, a master of disguise who would turn himself into a human target - provided you could meet his price."</ref> The character was adapted into a short-lived [[American Broadcasting Company|ABC]] television series starring [[Rick Springfield]] which debuted in July 1992.<ref>[http://www.tvguide.com/tvshows/human-target/202148 "Human Target on ABC"] TVGuide.com Retrieved January 31, 2011</ref> |

Infantino and writer [[Len Wein]] co-created the "[[Human Target]]" feature in ''[[Action Comics]]'' #419 (December 1972).<ref>McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 153: "Starting as a back-up feature in the pages of ''Action Comics'', scribe Len Wein and artist Carmine Infantino introduced Christopher Chance, a master of disguise who would turn himself into a human target - provided you could meet his price."</ref> The character was adapted into a short-lived [[American Broadcasting Company|ABC]] television series starring [[Rick Springfield]] which debuted in July 1992.<ref>[http://www.tvguide.com/tvshows/human-target/202148 "Human Target on ABC"] TVGuide.com Retrieved January 31, 2011</ref> |

||

After |

After consulting with screenwriter [[Mario Puzo]] on the plots of both ''[[Superman (film)|Superman: The Movie]]'' and ''[[Superman II|Superman II]]'',<ref>[http://www.wtv-zone.com/silverager/interviews/infantino.shtml "Carmine Infantino interview"] with Bryan Stroud</ref> Infantino collaborated with Marvel on the historic company-crossover publication ''[[Superman vs. the Amazing Spider-Man]]''. In January 1976, [[Warner Communications]] replaced Infantino with magazine publisher [[Jenette Kahn]], a person new to the comics field. Infantino returned to drawing freelance. |

||

===Later career=== |

===Later career=== |

||

Revision as of 23:04, 4 April 2013

This article is currently being heavily edited because its subject has recently died. Information about their death and related events may change significantly and initial news reports may be unreliable. The most recent updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. |

| Carmine Infantino | |

|---|---|

Infantino at the Big Apple Convention in Manhattan, October 2, 2010. | |

| Born | May 24, 1925 Brooklyn, New York City |

| Died | April 4, 2013 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Penciller, Editor |

Notable works | Detective Comics, Flash, Showcase, Star Wars |

| Awards | National Cartoonists Society Award, various Alley Awards. Expanded list. |

Carmine Infantino (May 24, 1925[1] – April 4, 2013), born in Brooklyn, New York,[2] was an American comic book artist and editor who was a major force in the Silver Age of Comic Books. He was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2000, and was cited in Comics Buyer's Guide Millennium Poll as the greatest penciller of all time.[3]

Early life

Carmine Infantino was born via midwife in his family's apartment in Brooklyn, New York City. His father, Pasquale "Patrick" Infantino, born in New York City, was originally a musician who played saxophone, clarinet, and violin, and had a band with composer Harry Warren, but in the poverty of the Great Depression he turned instead to a career as a licensed plumber. Carmine Infantino's mother, Angela Rosa DellaBadia, emigrated from Calitri, a hill town northeast of Naples, Italy.[4]

Infantino attended Public Schools 75 and 85 in Brooklyn before going on to the School of Industrial Art (later renamed the High School of Art and Design) in Manhattan. During his freshman year of high school, Infantino began working for Harry "A" Chesler, whose studio was one of a handful of comic-book "packagers" who created complete comics for publishers looking to enter the emerging field in the 1930s-1940s Golden Age of Comic Books. As Infantino recalled:[2]

I used to go around as a youngster into companies, go in and try to meet people — nothing ever happened. One day I went to this place on 23rd Street, this old broken-down warehouse, and I met Harry Chesler. Now, I was told he was a mean guy and he used people and he took artists. But he was very sweet to me. He said, 'Look, kid. You come up here, I'll give you a dollar a day, just study art, learn, and grow.' That was damn nice of him, I thought. He did that for me for a whole summer.[2]

Career

With Frank Giacoia penciling, Infantino inked the feature "Jack Frost" in USA Comics #3 (Jan. 1942). He wrote in his autobiography that

...Frank Giacoia and I were in constant contact. One day in '40 we decided to go up to Timely Comics, which later became Marvel, to see if we could get some work. They gave us a script called 'Jack Frost' and that story became our first published work. Frank did the pencils and I did the inking. Joe Simon was the editor and he offered us both a staff job. Frank quit school and took the job. I wanted desperately to quit school and I told my father that it was a great opportunity. He said, 'No way! You're gonna finish school.' Things were very bad, he was desperate for money, but he wouldn't let me quit school. He said, 'School comes first. If you're that good, the job will be there later.' I can't love the man enough for that. So Frank took the job and I didn't. I was 15 or 16 and I just kept making my rounds in the early '40s, looking for freelance work while continuing my studies.[5]

Infantino would eventually work for several publishers during the decade, drawing Airboy and the Heap for Hillman Periodicals; working for packager Jack Binder, who supplied Fawcett Comics; briefly at Holyoke Publishing; then landing at DC Comics. Infantino's first published work for DC was "The Black Canary", a six page Johnny Thunder story which introduced the Black Canary character in Flash Comics #86 (August 1947).[6] Infantino's long association with the Flash mythos began with "The Secret City" a story in All-Flash #31 (Oct.-Nov. 1947).[7] He additionally became a regular artist of the Golden Age Green Lantern and the Justice Society of America.

During the 1950s, Infantino freelanced for Joe Simon and Jack Kirby's company, Prize Comics, drawing the series Charlie Chan, which in particular shows the influence both of Kirby's and Milton Caniff's art styles. Back at DC, during a lull in the popularity of superheroes, Infantino drew Westerns, mysteries, science fiction comics. As his style evolved, he began to shed both the Kirbyisms and the gritty shading of Caniff, and develop a clean, linear style.

The Silver Age

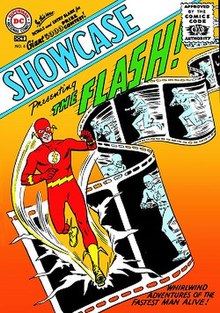

In 1956, DC editor Julius Schwartz assigned writer Robert Kanigher and artist Infantino to the company's first attempt at reviving superheroes: an updated version of the Flash that would appear in issue #4 (Oct. 1956) of the try-out series Showcase. Infantino designed the now-classic red uniform with yellow detail (reminiscent of the original Fawcett Captain Marvel), striving to keep the costume as streamlined as possible, and he drew on his design abilities to create a new visual language to depict the Flash's speed, making the figure a red and yellow blur. The eventual success of the new, science-fiction oriented Flash heralded the wholesale return of superheroes, and the beginning of what fans and historians call the Silver Age of comics.[8]

Infantino drew the "Flash of Two Worlds" a landmark[9] story that was published in The Flash #123 (Sept. 1961). It introduces Earth-Two, and more generally the concept of the multiverse, to DC Comics.[10] Infantino continued to work for Schwartz in his other features and titles, most notably "Adam Strange" in Mystery in Space, replacing Mike Sekowsky who did the penciling in Showcase 17-19. In 1964, Schwartz was made responsible for reviving the faded Batman titles. Writer John Broome and artist Infantino jettisoned the sillier aspects that had crept into the series (such as Ace the Bathound, and Bat-Mite) and gave the "New Look" Batman and Robin a more detective-oriented direction and sleeker draftsmanship that proved a hit combination.[11] Other features and characters Infantino drew at DC include "The Space Museum", and Elongated Man. With Gardner Fox, Infantino co-created Barbara Gordon as a new version of Batgirl in a story titled "The Million Dollar Debut of Batgirl!" in Detective Comics #359 (January 1967).[12] Deadman was created by writer Arnold Drake and Infantino and first appeared in Strange Adventures #205 (October 1967).[13][14] This story included the first known depiction of narcotics in a story approved by the Comics Code Authority.[15]

After Wilson McCoy, the artist of The Phantom comic strip, died, Infantino finished one of his last stories. Infantino was a candidate for taking over the Phantom Sunday strip after McCoy's death, but the job was instead given to Sy Barry.

DC Comics editorial director

In late 1966/early 1967, Infantino was tasked by Irwin Donenfeld with designing covers for the entire DC line. Stan Lee learned this and approached Infantino with a $22,000 offer to move to Marvel. Publisher Jack Liebowitz confirmed that DC could not match the offer, but could promote Infantino to the position of art director. Initially reluctant, Infantino accepted what Liebowitz posed as a challenge, and decided to stay with DC.[16] When DC was sold to Kinney National Company, Infantino was promoted to editorial director. He started by hiring new talent, and promoting artists to editorial positions. He hired Dick Giordano away from Charlton Comics, and made artists Joe Orlando, Joe Kubert and Mike Sekowsky editors. New talents such as artist Neal Adams and writer Denny O'Neil were brought into the company. Several of DC's older characters were revamped by O'Neil including Wonder Woman;[17] Batman; Green Lantern and Green Arrow; and Superman.[18]

In 1970, Infantino signed on Marvel Comics' star artist and storytelling collaborator Jack Kirby to a DC Comics contract. Beginning with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, Kirby created his Fourth World saga that wove through that existing title and three new series he created. After the "Fourth World" titles were canceled, Kirby created several other series for DC including OMAC, Kamandi, The Demon, and, together with former partner Joe Simon for one last time, a new incarnation of the Sandman before returning to freelancing for Marvel in 1975.

DC Comics publisher

Infantino was made DC's publisher in early 1971, during a time of declining circulation for the company's comics, and he attempted a number of changes. In an effort to raise revenue, he raised the cover price of DC's comics from 15 to 25 cents, simultaneously raising the page-count by adding reprints and new backup features.[19] Marvel met the price increase, then dropped back to 20 cents; DC stayed at 25 cents for about a year, a decision that ultimately proved bad for overall sales.[20][21]

Infantino and writer Len Wein co-created the "Human Target" feature in Action Comics #419 (December 1972).[22] The character was adapted into a short-lived ABC television series starring Rick Springfield which debuted in July 1992.[23]

After consulting with screenwriter Mario Puzo on the plots of both Superman: The Movie and Superman II,[24] Infantino collaborated with Marvel on the historic company-crossover publication Superman vs. the Amazing Spider-Man. In January 1976, Warner Communications replaced Infantino with magazine publisher Jenette Kahn, a person new to the comics field. Infantino returned to drawing freelance.

Later career

Infantino later drew for a number of titles for Warren Publishing and Marvel, including the latter's Star Wars, Spider-Woman, and Nova. During Infantino's tenure on the Star Wars series, it was one of the industry's top selling titles.[25] In 1981, he returned to DC Comics and co-created a revival of the "Dial H for Hero" feature with writer Marv Wolfman in a special insert in Legion of Super-Heroes #272 (February 1981).[26] Infantino returned to The Flash title with issue #296 (April 1981) and drew the book until its cancellation with issue #350 (October 1985). Other projects in the 1980s included penciling The Daring New Adventures of Supergirl,[27] a Red Tornado miniseries, and a comic book tie-in to the television series V. In 1990, he followed Marshall Rogers as artist of the Batman newspaper comic strip and drew the strip until its cancellation the following year.[28] During the 1990s Infantino also taught at the School of Visual Arts before retiring.[29] Despite his retirement, Infantino made appearances at comic conventions in the early 21st century[30]

In 2004, he sued DC for rights to characters he alleges to have created while he was a freelancer for the company. These include several Flash characters including Wally West, Iris West, Captain Cold, Captain Boomerang, Mirror Master, and Gorilla Grodd, as well as the Elongated Man and Batgirl.[31]

Infantino wrote or contributed to two books about his life and career: The Amazing World of Carmine Infantino (Vanguard Productions, ISBN 1-887591-12-5), and Carmine Infantino: Penciler, Publisher, Provocateur (Tomorrows Publishing, ISBN 1-60549-025-3)

Infantino was the uncle of Massachusetts musician Jim Infantino, of the band Jim's Big Ego.[32] He contributed the cover art to the group's album They're Everywhere, which features a song about the Flash called "The Ballad of Barry Allen."[33]

Bibliography

Interior pencil art includes:

DC

- Action Comics (Human Target) #419 (1972); (Superman, Nightwing, Green Lantern, Deadman) #642 (1989)

- Adventure Comics (Black Canary) #399 (1970); (Dial H for Hero) #479-485, 487-490 (1981–82)

- Adventures of Rex, the Wonder Dog (Detective Chimp) #1-4, 6, 13, 15-46 (1952–1959)

- Batman #165-175, 177, 181, 183-184, 188-192, 194-199, 208, 220, 234-235, 255, 258-259, 261-262 (1964–1975)

- Best of DC (Teen Titans) #18 (1981)

- The Brave and the Bold #67, 72, 172, 183, 190, 194 (1966–83)

- Danger Trail (miniseries) #1-4 (1993)

- DC Challenge #3 (1986)

- DC Comics Presents (Superman and the Flash) #73 (1984)

- DC Comics Presents: Batman (Julius Schwartz tribute issue) (2004)

- Detective Comics (Batman): #327, 329, 331, 333, 335, 337, 339, 341, 343, 345, 347, 349, 351, 353, 355, 357, 359, 361, 363, 366-367, 369; (Elongated Man): #327-330, 332-342, 344-358, 362-363, 366-367, 500 (1964–67, 1981)

- Flash #105-174 (1959–67), #296-350 (1981–85)

- Green Lantern, vol. 2, #53 (1967); (Adam Strange): #137, 145-147; (Green Lantern Corps) #151-153 (1981–82)

- House of Mystery #294, 296 (1981)

- Justice League of America #200, 206 (1982)

- Legion of Super-Heroes (Dial "H" for Hero preview) #272; (backup story) #289 (1981–1982)

- Mystery in Space #117 (1981)

- Phantom Stranger #1-3, 5-6 (1952–53)

- Red Tornado, miniseries, #1-4 (1985)

- Secret Origins (Adam Strange) #17; (Gorilla Grodd) #40; (Space Museum) #50; (Flash) Annual #2 (1987–90)

- Showcase (Flash) #4, 8, 13, 14 (1956–58)

- Strange Adventures (Deadman) #205 (1967)

- Super Powers, miniseries, #1-4 (1986)

- Supergirl, vol. 2, #1-20, 22-23 (1982–84)

- Superman (Supergirl) #376; (Superman) #404 (1982–85)

- Superman meets the Quik Bunny (1987)

- Teen Titans #27, 30 (1970)

- V #1-3, 6-16 (1985–86)

- World's Finest Comics (Hawkman) #276, 282 (1982)

Marvel

- Avengers #178, 197, 203, 244 (1978–84)

- Captain America #245 (1980)

- Daredevil #149-150, 152 (1977–78)

- Defenders #55-56 (1978)

- Ghost Rider #43-44 (1980)

- Howard the Duck #21, 28 (1978)

- Incredible Hulk #244 (1980)

- Iron Man #108-109, 122, 158 (1978–82)

- Marvel Fanfare (Doctor Strange) #8; (Shanna, the She-Devil) #56 (1991)

- Marvel Preview (Star-Lord) #14-15 (1978)

- Marvel Team-Up #92-93, 97, 105 (1980–81)

- Ms. Marvel #14, 19 (1978)

- Nova #15-20, 22-25 (1977–79)

- Savage Sword of Conan #34 (1978)

- Spider-Woman #1-19 (1978–79)

- Star Wars #11-15, 18-37, 45-48, Annual #2 (full art); #53-54 (along with Walt Simonson) (1978–82)

- Super-Villain Team-Up #16 (May 1979)

- What If (Nova) #15; (Ghost Rider, Spider-Woman, Captain Marvel) #17 (1979)

Warren

- Creepy #83-90, 93, 98 (1976–78)

- Eerie #77, 79-84 (1976–77)

- Vampirella (backup stories) #57-60 (1977)

Awards

Infantino's awards include:

- 1958 National Cartoonists Society Award, Best Comic Book

- 1961 Alley Award, Best Single Issue: The Flash #123 (with Gardner Fox)

- 1961 Alley Award, Best Story: "Flash of Two Worlds", The Flash #123 (with Gardner Fox)

- 1961 Alley Award, Best Artist

- 1962 Alley Award, Best Book-Length Story: "The Planet that Came to a Standstill!", Mystery in Space #75 (with Gardner Fox)

- 1962 Alley Award, Best Pencil Artist

- 1963 Alley Award, Best Artist

- 1964 Alley Award, Best Short Story: "Doorway to the Unknown", The Flash #148 (with John Broome)

- 1964 Alley Award, Best Pencil Artist

- 1964 Alley Award, Best Comic Book Cover (Detective Comics #329 with Murphy Anderson)

- 1967 Alley Award, Best Full-Length Story: "Who's Been Lying in My Grave?", Strange Adventures #205 (with Arnold Drake)

- 1967 Alley Award, Best New Strip: "Deadman" in Strange Adventures (with Arnold Drake)

- 1969 special Alley Award for being the person "who exemplifies the spirit of innovation and inventiveness in the field of comic art"

- 1985: Named as one of the honorees by DC Comics in the company's 50th anniversary publication Fifty Who Made DC Great.[34]

Quotations

Nick Cardy on the popular but apocryphal anecdote, told by Julius Schwartz, about Carmine Infantino firing Cardy over not following a cover layout, only to rehire him moments later when Schwartz praised the errant cover art:

[A]t one of the conventions ... I said, 'You know, Carmine, Julie Schwartz wrote something in [his autobiography] that I don't remember at all and it doesn't sound like you at all'. And I told him the incident ... and he said, 'That's crazy. You know I always loved your work. Gee, you were one of the best artists in the business. The guy's crazy'. So I said, 'Okay, come on'. We went over to Julie Schwartz's table and we told him what our problem was. And Carmine and I said, 'We don't remember the incident'. So Julie said, 'Well, it's a good story, anyway'. [laughs] And that was it. He let it go at that. [laughs] He just made it up.[35]

References

- ^ Miller, John Jackson (June 10, 2005). "Comics Industry Birthdays". Comics Buyer's Guide. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Text "John Jackson Miller" ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Carmine Infantino Interview". The Comics Journal. (online excerpts from print interview). Archived from the original on 2007-02-07. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- ^ "Guests of Honor," New York Comic-Con #4 program booklet (2009), p. 10.

- ^ Carmine Infantino with J. David Spurlock, The Amazing World of Carmine Infantino: An Autobiography (Vanguard Productions, 2000; ISBN 1-887591-11-7), pp. 12-13

- ^ Infantino, J. David Spurlock, p. 19

- ^ Wallace, Daniel; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1940s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

Debuting as a supporting character in a six-page Johnny Thunder feature written by Robert Kanigher and penciled by Carmine Infantino, Dinah Drake [the Black Canary] was originally presented as a villain...The Black Canary's introduction in August [1947]'s Flash Comics #86 represented [Infantino's] first published work for DC.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wallace "1940s" in Dolan, p. 56 "The first Carmine Infantino art of the Flash character appeared in this issue's twelve-page adventure "The Secret City"...it was Infantino's work on the Flash that would become the cornerstone of his career.

- ^ Irvine, Alex "1950s" in Dolan, p. 80 "The arrival of the second incarnation of the Flash in [Showcase] issue #4 is considered to be the official start of the Silver Age of comics."

- ^ "Julius Schwartz". The Daily Telegraph. February 24, 2004. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|deadurl=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McAvennie, Michael "1960s" in Dolan, p. 103 "This classic Silver Age story resurrected the Golden Age Flash and provided a foundation for the Multiverse from which he and the Silver Age Flash would hail."

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 110: "The Dark Knight received a much-needed facelift from new Batman editor Julius Schwartz, writer John Broome, and artist Carmine Infantino. With sales at an all-time low and threatening the cancelation of one of DC's flagship titles, their overhaul was a lifesaving success for DC and its beloved Batman."

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 122 "Nine months before making her debut on Batman, a new Batgirl appeared in the pages of Detective Comics...Yet the idea for the debut of Barbara Gordon, according to editor Julius Schwartz, was attributed to the television series executives' desire to have a character that would appeal to a female audience and for this character to originate in the comics. Hence, writer Gardner Fox and artist Carmine Infantino collaborated on 'The Million Dollar Debut of Batgirl!'"

- ^ Greenberger, Robert (2008). "Deadman". In Dougall, Alastair (ed.). The DC Comics Encyclopedia. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 96. ISBN 0-7566-0592-X.

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 125 "In a story by scribe Arnold Drake and artist Carmine Infantino, circus aerialist Boston Brand learned there was much more to life after his death...Deadman's origin tale was the first narcotics-related story to require prior approval from the Comics Code Authority."

- ^ Cronin, Brian (September 24, 2009). "Comic Book Legends Revealed #226". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

One comic that I know preceded the 1971 amendment [to the Comics Code] was Strange Adventures #205, the first appearance of Deadman!...a clear reference to narcotics, over THREE YEARS before Marvel Comics would have to go without the Comics Code to do an issue about drugs.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|deadurl=(help) - ^ Ro, Ronin. Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution, p. 117-118 (Bloomsbury, 2004)

- ^ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 131 "Carmine Infantino wanted to rejuvenate what had been perceived as a tired Wonder Woman, so he assigned writer Denny O'Neil and artist Mike Sekowsky to convert the Amazon Princess into a secret agent. Wonder Woman was made over into an Emma Peel type and what followed was arguably the most controversial period in the hero's history."

- ^ In, respectively, Wonder Woman #178 (Sept.-Oct. 1968), Detective Comics #395 (Jan. 1970), Green Lantern #76 (April 1970), and Superman #233 (Jan. 1971) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p.144: "Although decreasing sales and inflation dictated a hefty cover price increase from 15 to 25 cents, Infantino saw to it that extra pages containing classic reprints and new back-up features were added to DC titles."

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 150: "Despite its renewed excitement, and a mid-year cover price decrease to 20 cents, DC's line of superhero comics was experiencing uneven sales results in 1972."

- ^ Levitz, Paul (2010). 75 Years of DC Comics The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Taschen America. p. 451. ISBN 978-3-8365-1981-6.

Marvel took advantage of this moment to surpass DC in title production for the first time since 1957, and in sales for the first time ever.

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 153: "Starting as a back-up feature in the pages of Action Comics, scribe Len Wein and artist Carmine Infantino introduced Christopher Chance, a master of disguise who would turn himself into a human target - provided you could meet his price."

- ^ "Human Target on ABC" TVGuide.com Retrieved January 31, 2011

- ^ "Carmine Infantino interview" with Bryan Stroud

- ^ Miller, John Jackson (March 7, 1997), "Gone but not forgotten: Marvel Star Wars series kept franchise fans guessing between films", Comics Buyer's Guide, no. 1216, p. 46,

The industry's top seller? We don't have complete information from our Circulation Scavenger Hunt for the years 1979 and 1980, but a very strong case is building for Star Wars as the industry's top-selling comic book in 1979 and its second-place seller (behind Amazing Spider-Man) in 1980.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. "1980s" in Dolan, p. 192 "Within a sixteen-page preview in Legion of Super-Heroes #272...was "Dial 'H' For Hero," a new feature that raised the bar on fan interaction in the creative process. The feature's story, written by Marv Wolfman, with art by Carmine Infantino, saw two high-school students find dials that turned them into super-heroes. Everything from the pair's civilian clothes to the heroes they became was created by fans writing in. This concept would continue in the feature's new regular spot within Adventure Comics."

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Dolan, p. 198 "With the guidance of writer Paul Kupperberg and prolific artist Carmine Infantino, Supergirl found a home in the city of Chicago in a new ongoing series."

- ^ Greenberger, Robert; Manning, Matthew K. (2009). The Batman Vault: A Museum-in-a-Book with Rare Collectibles from the Batcave. Running Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-7624-3663-8.

Shortly after the 1989 feature [film], Batman even returned to the funny pages for a bit, in a comic strip by writer William Messner-Loebs...Lacking enough support from various papers to make it financially feasible, the new comic strip folded after two years, despite Carmine Infantino trying his hand at its art chores.

- ^ Coville, Jamie (2007). "Interview with Carmine Infantino". Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Michael Eury (2005). The Justice League Companion: A Historical and Speculative Overview of the Silver Age Justice League of America. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 1893905489.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brady, Matt (June 15, 2004). "Looking at Infantino's Complaint". Newsarama. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; September 14, 2007 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Other Infantinos". jiminfantino.com. Jim Infantino. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ "Jim's Big Ego Discography: They're Everywhere". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ Marx, Barry, Cavalieri, Joey and Hill, Thomas (w), Petruccio, Steven (a), Marx, Barry (ed). "Carmine Infantino DC Revitalized" Fifty Who Made DC Great, p. 37 (1985). DC Comics.

- ^ Back Issue #13, December 2005, p. 6

External links

- CarmineInfantino,com (fan site). WebCitation archive.

- Carmine Infantino at the Grand Comics Database

- NCS Awards