Lehigh Valley Railroad: Difference between revisions

m undo disambig link to Waverly, Tioga County, New York |

|||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

* [http://www.lvrrhs.org/history/index.htm Lehigh Valley Railroad Historical Society] |

* [http://www.lvrrhs.org/history/index.htm Lehigh Valley Railroad Historical Society] |

||

* [http://www.rootsweb.com/~paluzern/lvrr100.htm Luzerne County PAGenWeb (One Hundred Years of The Lehigh Valley)] |

* [http://www.rootsweb.com/~paluzern/lvrr100.htm Luzerne County PAGenWeb (One Hundred Years of The Lehigh Valley)] |

||

* [http://www.wnyrails. |

* [http://www.wnyrails.net/railroads/lv/lv_home.htm Lehigh Valley pages on Western NY Railroad Archive] |

||

*[http://digital.lib.lehigh.edu/beyondsteel/ Beyond Steel: An Archive of Lehigh Valley Industry and Culture] |

*[http://digital.lib.lehigh.edu/beyondsteel/ Beyond Steel: An Archive of Lehigh Valley Industry and Culture] |

||

* Lamb, Tammy. (1998). [http://www.rootsweb.com/~paluzern/lvrr100.htm Lehigh Valley Railroad]. Retrieved July 26, 2004. |

* Lamb, Tammy. (1998). [http://www.rootsweb.com/~paluzern/lvrr100.htm Lehigh Valley Railroad]. Retrieved July 26, 2004. |

||

Revision as of 02:20, 20 September 2013

| |

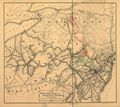

LV system map | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | New York City, New York |

| Reporting mark | LV |

| Locale | New Jersey Pennsylvania New York |

| Dates of operation | 1846–1976 |

| Successor | Conrail |

| Technical | |

| Length | 1,362 miles (2,192 kilometres) |

The Lehigh Valley Railroad (reporting mark LV) was one of several Class I railroads located in Northeastern United States built in the middle of the 19th-century for the purpose of breaking the effective monopoly held on the Lehigh Valley by the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company by providing another means of transporting anthracite coal besides the Lehigh Canal.[1]

As one of the early companies servicing the coal fields it grew both by acquisition and planned construction, gradually extending it's trackage up through the South Anthracite Coal Fields and into the North Fields via it's connections with the Wyoming Valley. Following the Susquehanna northwest from Duryea Yard through Waverly, New York, the railroad extended eventually to Buffalo New York. It was sometimes known as the Route of the Black Diamond, the name of an express passenger train it ran connecting New York City to Buffalo via Pittston and Waverly and Elmira New York, while the express service was named after the high grade anthracite it transported.

History

Anthracite coal was discovered in 1791 on Summit Hill a few miles upslope over Nesquehoning Mountain from Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania on the Lehigh River (Mauch Chunk was renamed Jim Thorpe in 1954). The only practical means to transport the coal to a sizable market was to boat it down the often unnavigable Lehigh River, after packing it on mules through the mountains to the river.

A Navigation (or erroneously, a canal) was constructed on the river by LC&N in 1820-22, and the Lehigh Canal, was churning out head-turning quantities of anthracite by 1824. In 1827 LC&N built the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway to feed the chutes loading the barges exporting coal down to the Delaware (see image at left) and by the 1830s the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company had a near-monopoly on the mining and transportation of coal in the Lehigh Valley region. To break the monopoly and also to improve transportation, the 'Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill & Susquehanna Railroad' was incorporated in 1846 to build a line from Mauch Chunk to Easton, Pennsylvania, where the Lehigh River flows into the Delaware. Construction did not begin until 1851; then with the management and the financing of Asa Packer work began in earnest.[2] The railroad was renamed the Lehigh Valley Railroad (LV) in 1853, and it was opened from Easton to Mauch Chunk (along the east bank or north side of the Lehigh[3]) in September 1855.[4][2]

The railroad began to grow both by new construction and by consolidation with existing railroads. In 1866, the year the Lehigh & Mahanoy Railroad (L&M) merged with the LV, Alexander Mitchell, master mechanic of the L&M, designed a freight locomotive with a 2-8-0 wheel arrangement and named it "Consolidation" — the name became the standard designation for that wheel arrangement. [5] The LV reached north into the Wyoming Valley to Wilkes-Barre in 1867, the same year that Lehigh Coal and Navigation's Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad, originally a White Haven-to-Wilkes-Barre shortline, opened a line south along the right bank of the Lehigh River on the opposite bank from the LV from Mauch Chunk through Lehighton at White Haven both railways were necessarily, as in other places to the north, sharing the same bank.[4] Both these railroads had to travel through the scenic Lehigh River Gorge, the site of several tourism tours including railway excursions, and both sets of trackage are still in existence, as are the yards on both banks of the river at Jim Thorpe and Lehighton-Packerton.

In 1865, Packer purchased a flood-damaged canal along the Susquehanna above Pittston-Duryea yard at the confluence of the Lackawanna, renamed it the Pennsylvania & New York Canal & Railroad (P&NY), and used its towpath as a roadbed. The P&NY was completed to a connection in Sayre, Pennsylvania with the New York & Erie at Waverly, New York, in 1869, giving the LV an outlet to the west.[6] In 1876, the LV furnished the material and the money necessary for Erie to lay a third rail to accommodate standard gauge trains in its line from Waverly to Buffalo, to eliminate the need to transfer freight and passengers at Waverly.[7] LV then leased the P&NY in 1888.[4]

At its eastern end LV saw its connecting routes taken over by rival railroads: the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (DL&W) acquired the Morris & Essex in 1868, and the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ), formerly considered friendly, leased the Lehigh & Susquehanna in 1871, getting a line parallel to the LV all the way from Easton to Wilkes-Barre.[8] LV bought the Morris Canal across New Jersey chiefly for its property on New York Harbor at Jersey City. It assembled a line to Perth Amboy in 1875, but not until 1899 did LV reach its Jersey City property on its own rails.[4][9]

LV's use of the Erie Railroad's rails (or, more accurately, one of its own and one of Erie's) to reach Buffalo was not completely satisfactory. In 1876, LV got control of the Geneva, Ithaca and Sayre Railroad, which put it into Geneva, New York, the center of the Finger Lakes region.[10] In the early 1880s, LV built a terminal railroad and a station in Buffalo and established a Great Lakes shipping line (whose flag became the emblem of the railroad). Construction of a line from Geneva to Buffalo and a freight bypass to avoid steep grades on the Geneva, Ithaca and Sayre began in 1889. In 1890 LV merged the companies involved in building the new line as the Lehigh Valley Rail Way. The Buffalo extension was opened in September 1892.[4]

LV lines in western New York included a branch from the new line to Rochester; the former Southern Central Railroad from Sayre to North Fair Haven on Lake Ontario; and the Elmira, Cortland & Northern Railroad, which meandered from Elmira through East Ithaca, Cortland, and Canastota to Camden — nothing came of a proposal to extend the line to Watertown, New York. In 1896 LV opened a short bypass around Buffalo from traffic to and from Canada.[4]

A few years earlier Archibald A. McLeod had started the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad (P&R) on a course of expansion with the backing of financiers J. P. Morgan and Anthony Drexel. The P&R negotiated quietly with the LV, which had a Great Lakes outlet for P&R's anthracite as well as its own. The financial arrangement seemed beneficial to LV, too, which had just invested a great deal of money getting to Buffalo and was noticing a decline in anthracite traffic. In February 1892, the P&R leased the LV (as well as the CNJ). Morgan and Drexel were suddenly alarmed by the growth of the P&R (it was pursuing the Boston and Maine Railroad by then) and withdrew their support. The P&R collapsed into receivership. The lease of the LV was terminated in 1893.[4][8]

J. P. Morgan agreed to fund the LV. He moved its general offices from Philadelphia to New York and began rebuilding the railroad. The independent stockholders of the line protested the diversion of money from dividends into physical plant and regained control in 1902. Several other railroads bought blocks of LV stock — New York Central (NYC), Reading (RDG), Erie, DL&W, and CNJ — and the railroad became part of William Moore's short-lived Rock Island system. In 1903 the company underwent some corporate simplification, merging and dissolving a number of subsidiaries.[4]

In 1913 LV's passenger trains were evicted from the Pennsylvania Railroad's (PRR) Jersey City terminal at Exchange Place and moved to the CNJ's station at Communipaw Terminal; in 1918 under the direction of the United States Railroad Administration they were moved into the PRR's Pennsylvania Station in New York City. It remained LV's New York terminus until the end of passenger service in 1961. Several events during the 1910s adversely affected LV's revenues: a munitions explosion on Black Tom Island on the Jersey City waterfront in 1916, the divestiture of the Great Lakes shipping operation in 1917 (required by the Panama Canal Act), the divestiture of the coal mining subsidiary (required by the Sherman Antitrust Act), and a drop in anthracite traffic as oil and gas became the dominant home heating fuels.[4]

The Interstate Commerce Commission proposal in the 1920s called for four major railroad systems in the East. The response of Leonor F. Loree, president of the Lehigh and Hudson River Railroad (L&HR), was a proposal for a fifth system, to include the Delaware and Hudson; LV; Wabash; Wheeling and Lake Erie; and Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh.[11] Loree purchased large amounts of LV stock, but not enough to gain control. He was later able to sell his shares in Wabash and LV to the PRR, which suddenly found itself with 31% of LV's common stock: enough to keep LV from falling into the hands of the NYC. However, the PRR exercised no noticeable influence on the policies and operations of the LV.[4]

LV entered the Great Depression with its physical plant in good shape and with little debt of its own maturing in the next few years. However, the maturation of bonds of the Lehigh Valley Coal Company, New Jersey state taxes, and interest on debt soon had the railroad in debt to the federal government for nearly $8 million. Highways were taking away passenger and freight business. LV began to prune its branches, starting with the former Elmira, Cortland & Northern. At the end of the 1930s LV made a valiant effort to attract passenger business by hiring designer Otto Kuhler to streamline its old cars and locomotives (Kuhler had previous designed "The Mountaineer" passenger equipment for the New York, Ontario and Western Railway). World War II brought a tremendous surge of business to on-line Army bases and LV's port facilities, but LV's decline resumed quickly when the war was over.[4][12]

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 273 |

| 1933 | 111 |

| 1944 | 453 |

| 1960 | 31 |

| 1970 | 0 |

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 5418 |

| 1933 | 2965 |

| 1944 | 9388 |

| 1960 | 2981 |

| 1970 | 2915 |

The route chosen for the New York State Thruway Niagara extension in downtown Buffalo lay along the LV's right of way, so, after first considering renting facilities from another railroad, LV constructed and opened a new terminal in Buffalo in 1955. That same year Hurricane Diane inflicted severe damage on much of LV's line in Pennsylvania, with attendant costs of rebuilding. The next year, 1956, was to be LV's last profitable year.[4]

On the New York-Buffalo run, LV's passenger trains competed with the newer and faster ones of the DL&W and the NYC as well as intercity buses using the new Thruway. In May 1959 LV discontinued all but two of its mainline passenger trains, including the daylight "Black Diamond." Those two, the New York-Lehighton John Wilkes and the overnight New York-Toronto Maple Leaf, lasted less than two years longer. LV was one of the first major railroads to shed all passenger service and offer only freight service.[4] Relief from passenger losses made no difference. LV's financial situation continued to worsen. In 1961 the PRR bought all the outstanding stock to protect its previous investment in the LV.[13] LV continued to prune branches and reduce double track to single and teamed up with CNJ to eliminate duplicate lines between Easton and Wilkes-Barre. In 1972 LV assumed all of CNJ's operations in Pennsylvania.[4]

One of the conditions of the creation of the Penn Central Transportation Company (PC) in 1968 (a long-discussed merger of the PRR, NYC and the New Haven) was that LV be offered to Norfolk and Western Railway and Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. Neither wanted it. PC declared bankruptcy on June 21, 1970, and LV filed for bankruptcy protection three days later.[14]

LV's situation got no better during the next six years. Its properties were taken over by Conrail on April 1, 1976, as were those of the Erie Lackawanna, Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines, CNJ, L&HR, RDG, and PC.[15] Most track west of Van Etten Junction, New York (where the Seneca Lake bypass split from the original line to Ithaca and Geneva) was considered redundant and abandoned.[4]

Portions still operated by other railroads

- Finger Lakes Railway/Ontario Central Railroad

- Genesee Valley Transportation (Depew, Lancaster & Western)

- Livonia, Avon and Lakeville Railroad

- New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway

- Reading & Northern

Passenger operations

The LVRR operated several named trains in the post-World War II era. Among them:

- No. 11 Star

- No. 4 Major

- No. 7/8 Maple Leaf - Toronto - New York City, via New York's Finger Lakes region and NE Pennsylvania

- No. 9/10 The Black Diamond - Buffalo - New York City, as a truncated counterpart to the Maple Leaf.

- No. 23/24 Lehighton Express

- No. 25/26 Asa Packer

- No. 28/29 John Wilkes

The LVRR's passenger services were at a comparative disadvantage to its competitors in the region, the Erie Railroad and the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. The LV by-passed important cities served by these roads including Corning, Elmira and Binghamton in favor of Geneva and Ithaca. In Pennsylvania the LV took a long route via Wilkes-Barre and Bethlehem, compared to the DL&W's modernized route via Scranton.

The primary passenger motive power for the LV in the diesel era was the ALCO PA-1 car body diesel-electric locomotive, of which the LV had fourteen. These locomotives were also used in freight service during and after the era of LV passenger service. A pair of ALCO FA-2 FB-2 car body diesel-electric locomotives were also purchased to augment the PAs when necessary. These were FAs with steam generators, but they were not designated as FPA-2 units.

Gallery

-

Milestone events and acquisitions of LV

-

LV system map, circa 1870

-

1884 map of PRR, RDG and LV railroads

-

Black Diamond Express Monthly publication, January 1906

-

1866 LV "Consolidation" locomotive, #63

-

Map of the Jersey City terminal

-

Annual dividends of the Lehigh Valley Railroad

-

Barge 79, now a museum in South Brooklyn

See also

References

- ^ Transcript of Record No. 570. Records and briefs of the United States Supreme Court. Oct 10, 1908.

- ^ a b Henry, Mathew Schropp (1860). History of the Lehigh Valley. pp. 395–400.

- ^ USGS Topo map series, quadrant: lehi22nw.jpg shows LVRR on the east bank north of the river, the CNJ on the south bank through the RBMN yard and 'historic' station in Jim Thorpe.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Drury, George H. (1994). The Historical Guide to North American Railroads: Histories, Figures, and Features of more than 160 Railroads Abandoned or Merged since 1930. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 172–175. ISBN 0-89024-072-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Harry E. Packer". New York Times. Feb 2, 1884.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Fiscal Year 1867.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Fiscal Year 1876.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Jones, Eliot (1914). The Anthracite Coal Combination in the United States. Harvard University Press.

- ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Fiscal Year 1871.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Fiscal Year 1889.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Loree Plan Loses to 4-system Merger". New York Times. Apr. 6, 1928.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Lehigh Revamping Authorized by ICC". New York Times. Feb. 9, 1949.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Pennsylvania Railroad Seeking all the Stock of Lehigh Valley". New York Times. Dec. 17, 1960.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Lehigh Line Asks Reorganization". New York Times. July 25, 1970.

- ^ Drury, George H. (1994). The Train Watcher's Guide to North American Railroads. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 84–88. ISBN 0-89024-131-87.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Lehigh Valley Railroad Historical Society

- Luzerne County PAGenWeb (One Hundred Years of The Lehigh Valley)

- Lehigh Valley pages on Western NY Railroad Archive

- Beyond Steel: An Archive of Lehigh Valley Industry and Culture

- Lamb, Tammy. (1998). Lehigh Valley Railroad. Retrieved July 26, 2004.

- Mancuso, James. Lehigh Valley Railroad. Retrieved December 21, 2005.

- Schaller, Ed. Lehigh Valley Railroad Modeler. Retrieved December 22, 2005.

- Lawrence, Scot. Lehigh Valley Railroad Survivors. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- Campbell, John W. Lehigh Valley Railroad. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- Lehigh Valley Railroad

- Former Class I railroads in the United States

- Standard gauge railways in the United States

- Defunct Pennsylvania railroads

- Defunct New Jersey railroads

- Defunct New York railroads

- Railroads transferred to Conrail

- Lehigh Valley

- Predecessors of Conrail

- Railway companies established in 1853

- Railway companies disestablished in 1976

- Conrail