The Amazing Spider-Man: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 226: | Line 226: | ||

*[http://www.marvel.com/universe/Spider-Man_(Peter_Parker) Spider-Man] at Marvel Comics wikia |

*[http://www.marvel.com/universe/Spider-Man_(Peter_Parker) Spider-Man] at Marvel Comics wikia |

||

*[http://www.coverbrowser.com/covers/amazing-spider-man ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' cover gallery] |

*[http://www.coverbrowser.com/covers/amazing-spider-man ''The Amazing Spider-Man'' cover gallery] |

||

*[http://spidermanvideos.info/ Spiderman Videos] |

|||

{{Spider-Man publications}} |

{{Spider-Man publications}} |

||

Revision as of 20:26, 16 May 2014

| The Amazing Spider-Man | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Non-Pereil Publishing Group (#1–67) Perfect Film & Chemical Corp. (#68–69) Magazine Management Co. (#70–118) Marvel Comics (#119–700) |

| Schedule | Monthly |

| Genre | |

| Publication date | (vol. 1) March 1963 - November 1998 (vol. 2) January 1999 - November 2003 (vol. 1 continued) December 2003 - February 2013 (2014 relanch) April 2014 - present |

| No. of issues | (vol. 1) 442 (#1-441 plus #-1) and 28 Annuals (vol. 2) 58 (vol. 1 continued) 209 (#500-700 plus issues numbered 654.1, 679.1, 699.1, 700.1, 700.2, 700.3, 700.4, and 700.5) (2014 relaunch) Ongoing, started from #1 |

| Main character(s) | Spider-Man |

| Creative team | |

| Created by | Stan Lee Steve Ditko |

| Written by | List

|

| Penciller(s) | List

|

| Inker(s) | |

The Amazing Spider-Man is an American comic book series published by Marvel Comics, featuring the adventures of the fictional superhero Spider-Man. Being the mainstream continuity of the franchise, it began publication in 1963 as a monthly periodical and was published continuously, with a brief interruption in 1995, until its relaunch with a new numbering order in 1999. In 2003 the series reverted to the numbering order of the first volume. The title has occasionally been published biweekly, and was published three times a month from 2008 to 2010. A film named after the comic was released July 3, 2012.

After DC Comics' relaunch of Action Comics and Detective Comics with new #1 issues in 2011, it had been the highest-numbered American comic still in circulation until it was cancelled. The title ended its 50-year run as a continuously published comic with issue #700 in December 2012. It was replaced by The Superior Spider-Man as part of the Marvel NOW! relaunch of Marvel's comic lines.[1]

The title was relaunched from in April 2014, starting fresh from issue #1, after the "Goblin Nation" story arc published in The Superior Spider-Man and Superior Spider-Man Team-Up.

Publication history

The character was created by writer-editor Stan Lee and artist and co-plotter Steve Ditko,[2] and the pair produced 38 issues from March 1963 to July 1966. Ditko left after the 38th issue, while Lee remained as writer until issue 100. Since then, many writers and artists have taken over the monthly comic through the years, chronicling the adventures of Marvel's most identifiable hero.

The Amazing Spider-Man has been the character's flagship series for his first fifty years in publication, and was the only monthly series to star Spider-Man until Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man in 1976 (although 1972 saw the debut of Marvel Team-Up, with the vast majority of issues featuring Spider-Man along with a rotating cast of other Marvel characters). Most of the major characters and villains of the Spider-Man saga have been introduced in Amazing, and with few exceptions, it is where most key events in the character's history have occurred. The title was published continuously until #441 (Nov. 1998)[3] when Marvel Comics relaunched it as vol. 2, #1 (Jan. 1999),[4] but on Spider-Man's 40th anniversary, this new title reverted to using the numbering of the original series, beginning again with issue #500 (Dec. 2003) and lasting until the final issue, #700 (Dec. 2012).[5]

The 1960s

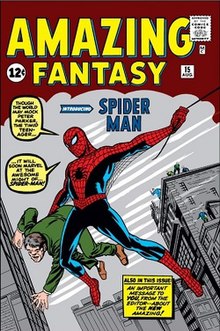

Due to strong sales on the character's first appearance in Amazing Fantasy #15, Spider-Man was given his own ongoing series in March 1963.[6] The initial years of the series, under Lee and Ditko, chronicled Spider-Man's nascent career with his civilian life as hard-luck yet perpetually good-humored teenager Peter Parker. Peter balanced his career as Spider-Man with his job as a freelance photographer for The Daily Bugle under the bombastic editor-publisher J. Jonah Jameson to support himself and his frail Aunt May. At the same time, Peter dealt with public hostility towards Spider-Man and the antagonism of his classmates Flash Thompson and Liz Allan at Midtown High School, while embarking on a tentative, ill-fated romance with Jameson's secretary, Betty Brant.

By focusing on Parker's everyday problems, Lee and Ditko created a groundbreakingly flawed, self-doubting superhero, and the first major teenaged superhero to be a protagonist and not a sidekick. Ditko's quirky art provided a stark contrast to the more cleanly dynamic stylings of Marvel's most prominent artist, Jack Kirby,[2] and combined with the humor and pathos of Lee's writing to lay the foundation for what became an enduring mythos.

Most of Spider-Man's key villains and supporting characters were introduced during this time. Issue #1 (March 1963) featured the first appearances of J. Jonah Jameson[7] and his astronaut son John Jameson,[8] and the supervillain the Chameleon.[7] It included the hero's first encounter with the superhero team The Fantastic Four. Issue #2 (May 1963) featured the first appearance of the Vulture[9] and the beginning of Parker's freelance photography career at the newspaper The Daily Bugle.[10]

The Lee-Ditko era continued to usher in a significant number of villains and supporting characters, including Doctor Octopus in #3 (July 1963);[11][12] the Sandman and Betty Brant in #4 (Sept. 1963);[13] the Lizard in #6 (Nov. 1963);[14][15] Living Brain in (#8, January, 1964); Electro in #9 (March 1964);[16][17] Mysterio in #13 (June 1964);[18] the Green Goblin in #14 (July 1964);[19][20] Kraven The Hunter in #15 (Aug. 1964);[21] reporter Ned Leeds in #18 (Nov. 1964);[22] and the Scorpion in #20 (Jan. 1965).[23] The Molten Man was introduced in #28 (Sept. 1965) which also featured Parker's graduation from high school.[24] Peter began attending Empire State University in #31 (Dec. 1965), the issue which featured the first appearances of friends and classmates Gwen Stacy[25] and Harry Osborn.[26] Harry's father, Norman Osborn first appeared in #23 (April 1965) as a member of Jameson's country club but is not named nor revealed as Harry's father until #37 (June 1966). One of the most celebrated issues of the Lee-Ditko run is #33 (Feb. 1966), the third part of the story arc "If This Be My Destiny...!", and featuring the dramatic scene of Spider-Man, through force of will and thoughts of family, escaping from being pinned by heavy machinery. Comics historian Les Daniels noted that "Steve Ditko squeezes every ounce of anguish out of Spider-Man's predicament, complete with visions of the uncle he failed and the aunt he has sworn to save."[27] Peter David observed that "After his origin, this two-page sequence from Amazing Spider-Man #33 is perhaps the best-loved sequence from the Stan Lee/Steve Ditko era."[28] Steve Saffel stated the "full page Ditko image from The Amazing Spider-Man #33 is one of the most powerful ever to appear in the series and influenced writers and artists for many years to come."[29] and Matthew K. Manning wrote that "Ditko's illustrations for the first few pages of this Lee story included what would become one of the most iconic scenes in Spider-Man's history."[30] The story was chosen as #15 in the 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time poll of Marvel's readers in 2001. Editor Robert Greenberger wrote in his introduction to the story that "These first five pages are a modern-day equivalent to Shakespeare as Parker's soliloquy sets the stage for his next action. And with dramatic pacing and storytelling, Ditko delivers one of the great sequences in all comics."[31]

Although credited only as artist for most of his run, Ditko would eventually plot the stories as well as draw them, leaving Lee to script the dialogue. A rift between Ditko and Lee developed, and the two men were not on speaking terms long before Ditko completed his last issue, The Amazing Spider-Man #38 (July 1966). The exact reasons for the Ditko-Lee split have never been fully explained.[32] Spider-Man successor artist John Romita, Sr., in a 2010 deposition, recalled that Lee and Ditko "ended up not being able to work together because they disagreed on almost everything, cultural, social, historically, everything, they disagreed on characters..."[33]

In successor penciler Romita Sr.'s first issue, #39 (Aug. 1966), nemesis the Green Goblin discovers Spider-Man's secret identity and reveals his own to the captive hero. Romita's Spider-Man – more polished and heroic-looking than Ditko's – became the model for two decades. The Lee-Romita era saw the introduction of such characters as Daily Bugle managing editor Robbie Robertson in #52 (Sept. 1967) and NYPD Captain George Stacy, father of Parker's girlfriend Gwen Stacy, in #56 (Jan. 1968). The most important supporting character to be introduced during the Romita era was Mary Jane Watson, who made her first full appearance in #42, (Nov. 1966),[34] although she first appeared in #25 (June 1965) with her face obscured and had been mentioned since #15 (Aug. 1964). Peter David wrote in 2010 that Romita "made the definitive statement of his arrival by pulling Mary Jane out from behind the oversized potted plant [that blocked the readers' view of her face in issue #25] and placing her on panel in what would instantly become an iconic moment."[35] Romita has stated that in designing Mary Jane, he "used Ann-Margret from the movie Bye Bye Birdie as a guide, using her coloring, the shape of her face, her red hair and her form-fitting short skirts."[36]

Lee and Romita toned down the prevalent sense of antagonism in Parker's world by improving Parker's relationship with the supporting characters and having stories focused as much on the social and college lives of the characters as they did on Spider-Man's adventures. The stories became more topical,[37] addressing issues such as civil rights, racism, prisoners' rights, the Vietnam War, and political elections.

Issue #50 (June 1967) introduced the highly enduring criminal mastermind the Kingpin,[38][39] who would become a major force as well in the superhero series Daredevil. Other notable first appearances in the Lee-Romita era include the Rhino in #41 (Oct. 1966),[40][41] the Shocker in #46 (March 1967),[42][43] the Prowler in #78 (Nov. 1969),[44] and the Kingpin's son, Richard Fisk, in #83 (April 1970).[45]

The 1970s

Several spin-off series debuted in the 1970s: Marvel Team-Up in 1972,[46] and The Spectacular Spider-Man in 1976.[47] A short-lived series titled Giant-Size Spider-Man began in July 1974 and ran six issues through 1975.[48] Spidey Super Stories, a series aimed at children ages 6–10, ran for 57 issues from October 1974 through 1982.[49][50] The flagship title's second decade took a grim turn with a story in #89-90 (Oct.-Nov. 1970) featuring the death of Captain George Stacy.[51] This was the first Spider-Man story to be penciled by Gil Kane,[52] who would alternate drawing duties with Romita for the next year-and-a-half and would draw several landmark issues.

One such story took place in the controversial issues #96-98 (May–July 1971). Writer-editor Lee defied the Comics Code Authority with this story, in which Parker's friend Harry Osborn, was hospitalized after tripping on LSD. Lee wrote this story upon a request from the U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare for a story about the dangers of drugs. Citing its dictum against depicting drug use, even in an anti-drug context, the CCA refused to put its seal on these issues. With the approval of Marvel publisher Martin Goodman, Lee had the comics published without the seal. The comics sold well and Marvel won praise for its socially conscious efforts.[53] The CCA subsequently loosened the Code to permit negative depictions of drugs, among other new freedoms.[54]

The "The Six Arms Saga" of #100-102 (Sept.–Nov. 1971) introduced Morbius, the Living Vampire. The second installment was the first Amazing Spider-Man story not written by co-creator Lee,[55] with Roy Thomas taking over writing the book for several months before Lee returned to write #105-110 (Feb.-July 1972).[56] Lee, who was going on to become Marvel Comics' publisher, with Thomas becoming editor-in-chief, then turned writing duties over to 19-year-old wunderkind Gerry Conway,[57] who scripted the series through 1975. Romita penciled Conway's first half-dozen issues, which introduced the gangster Hammerhead in #113 (Oct. 1972). Kane then succeeded Romita as penciler,[52] although Romita would continue inking Kane for a time.

The most memorable work of the Conway/Kane/Romita team was #121-122 (June–July 1973), which featured the death of Gwen Stacy at the hands of the Green Goblin in "The Night Gwen Stacy Died" in issue #121.[58][59][60] Her demise and the Goblin's apparent death one issue later formed a story arc widely considered as the most defining in the history of Spider-Man.[61] The aftermath of the story deepened both the characterization of Mary Jane Watson and her relationship with Parker.

In 1973, Gil Kane was succeeded by Ross Andru, whose run lasted from issue #125 (October 1973) to #185 (October 1978).[62] Issue #129 (Feb. 1974) introduced the Punisher,[63] who would become one of Marvel Comics' most popular characters. The Conway-Andru era featured the first appearances of the Man-Wolf in #124-125 (Sept.-Oct. 1973); the near-marriage of Doctor Octopus and Aunt May in #131 (April 1974); Harry Osborn stepping into his father's role as the Green Goblin in #135-137 (Aug.-Oct.1974); and the original "Clone Saga", containing the introduction of Spider-Man's clone, in #147-149 (Aug.-Oct. 1975). Archie Goodwin and Gil Kane produced the title's 150th issue (Nov. 1975) before Len Wein became writer with issue #151.[64] During Wein's tenure, Harry Osborn and Liz Allen dated and became engaged, J. Jonah Jameson was introduced to his eventual second wife, Marla Madison, and Aunt May suffered a heart attack. Wein's last story on Amazing was a five-issue arc in #176-180 (Jan.-May 1978) featuring a third Green Goblin (Harry Osborn’s psychiatrist, Bart Hamilton). Marv Wolfman, Marvel's editor-in-chief from 1975 to 1976, succeeded Wein as writer, and in his first issue, #182 (July 1978), had Parker propose marriage to Watson who refused, in the following issue.[65] Keith Pollard succeeded Ross Andru as artist shortly afterward, and with Wolfman introduced the likable rogue the Black Cat (Felicia Hardy) in #194 (July 1979).[66] As a love interest for Spider-Man, the Black Cat would go on to be an important supporting character for the better part of the next decade, and remain a friend and occasional lover into the 2010s.

The 1980s

The Amazing Spider-Man #200 (Jan. 1980) featured the return and death of the burglar who killed Spider-Man's Uncle Ben.[67] Writer Marv Wolfman and penciler Keith Pollard both left the title by mid-year, succeeded by Dennis O'Neil, a writer known for groundbreaking 1970s work at rival DC Comics,[68] and penciler John Romita, Jr.. O'Neil wrote two issues of The Amazing Spider-Man Annual which were both drawn by Frank Miller. The 1980 Annual featured a team-up with Doctor Strange[69] while the 1981 Annual showcased a meeting with the Punisher.[70] Roger Stern, who had written nearly 20 issues of sister title The Spectacular Spider-Man, took over Amazing with issue #224 (January 1982).[71] During his two years on the title, Stern augmented the backgrounds of long-established Spider-Man villains, and with Romita Jr. created the mysterious supervillain the Hobgoblin in #238-239 (March–April 1983).[72][73] Fans engaged with the mystery of the Hobgoblin's secret identity, which continued throughout #244-245 and 249-251 (Sept.-Oct. 1983 and Feb.-April 1984). One lasting change was the reintroduction of Mary Jane Watson as a more serious, mature woman who becomes Peter's confidante after she reveals that she knows his secret identity. Stern wrote "The Kid Who Collects Spider-Man" in The Amazing Spider-Man #248 (January 1984), a story which ranks among his most popular.[72][74]

By mid-1984, Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz took over scripting and penciling. DeFalco helped establish Parker and Watson's mature relationship, laying the foundation for the characters' wedding in 1987. Notably, in #257 (Oct. 1984), Watson tells Parker that she knows he is Spider-Man, and in #259 (Dec. 1984), she reveals to Parker the extent of her troubled childhood. Other notable issues of the DeFalco-Frenz era include #252 (May 1984), with the first appearance of Spider-Man's black costume, which the hero would wear almost exclusively for the next four years' worth of comics; the debut of criminal mastermind the Rose, in #253 (June 1984); the revelation in #258 (Nov. 1984) that the black costume is a living being, a symbiote; and the introduction of the female mercenary Silver Sable in #265 (June 1985).

Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz were both removed from The Amazing Spider-Man in 1986 by editor Owsley under acrimonious circumstances.[75] A succession of artists including Alan Kupperberg, John Romita, Jr., and Alex Saviuk penciled the book from 1987 to 1988; Owsley wrote the book for the first half of 1987, scripting the five-part "Gang War" story (#284-288) that DeFalco plotted. Former Spectacular Spider-Man writer Peter David scripted #289 (June 1987), which revealed Ned Leeds as being the Hobgoblin although this was retconned in 1996 by Roger Stern into Leeds not being the original Hobgoblin after all.

David Michelinie took over as writer in the next issue, for a story arc in #290-292 (July-Sept. 1987) that led to the marriage of Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson in Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21. The "Kraven's Last Hunt" storyline by writer J.M. DeMatteis and artists Mike Zeck and Bob McLeod crossed over into The Amazing Spider-Man #293 and 294.[76] Issue #298 (March 1988) was the first Spider-Man comic to be drawn by future industry star Todd McFarlane, the first regular artist on The Amazing Spider-Man since Frenz's departure. McFarlane revolutionized Spider-Man's look. His depiction – large-eyed, with wiry, contorted limbs, and messy, knotted, convoluted webbing – influenced the way virtually all subsequent artists would draw the character. McFarlane's other significant contribution to the Spider-Man canon was the design for what would become one of Spider-Man's most wildly popular antagonists, the supervillain Venom.[77] Issue #299 (April 1988) featured Venom's first appearance (a last-page cameo) before his first full appearance in #300 (May 1988). The latter issue featured Spider-Man reverting to his original red-and-blue costume.

Other notable issues of the Michelinie-McFarlane era include #312 (Feb. 1989), featuring the Green Goblin vs. the Hobgoblin; and #315-317 (May–July 1989), with the return of Venom. In July 2012, Todd McFarlane's original cover art for The Amazing Spider-Man #328 sold for a bid of $657,250, making it the most expensive American comic book art ever sold at auction.[78]

The 1990s

With a civilian life as a married man, the Spider-Man of the 1990s was different from the superhero of the previous three decades. McFarlane left the title in 1990 to write and draw a new series titled simply Spider-Man. His successor, Erik Larsen, penciled the book from early 1990 to mid-1991. After issue #350, Larsen was succeeded by Mark Bagley, who had won the 1986 Marvel Tryout Contest[79] and was assigned a number of low-profile penciling jobs followed by a run on New Warriors in 1990. Bagley penciled the flagship Spider-Man title from 1991 to 1996.[80]

Issues #361-363 (April–June 1992) introduced Carnage,[81] a second symbiote nemesis for Spider-Man. The series' 30th-anniversary issue, #365 (Aug. 1992), was a double-sized, hologram-cover issue[82] with the cliffhanger ending of Peter Parker's parents, long thought dead, reappearing alive. It would be close to two years before they were revealed to be impostors, who are killed in #388 (April 1994), scripter Michelinie's last issue. His 1987–1994 stint gave him the second-longest run as writer on the title, behind Stan Lee.

Issue #375 was released with a gold foil cover.[83] There was an error affecting some issues and which are missing the majority of the foil.[84]

With #389, writer J. M. DeMatteis, whose Spider-Man credits included the 1987 "Kraven's Last Hunt" story arc and a 1991–1993 run on The Spectacular Spider-Man, took over the title. From October 1994 to June 1996, Amazing stopped running stories exclusive to it, and ran installments of multi-part stories that crossed over into all the Spider-Man books. One of the few self-contained stories during this period was in #400 (April 1995), which featured the death of Aunt May — later revealed to have been faked (although the death still stands in the MC2 continuity). The "Clone Saga" culminated with the revelation that the Spider-Man who had appeared in the previous 20 years of comics was a clone of the real Spider-Man. This plot twist was massively unpopular with many readers,[85] and was later reversed in the "Revelations" story arc that crossed over the Spider-Man books in late 1996.

The Clone Saga tied into a publishing gap after #406 (Oct. 1995), when the title was temporarily replaced by The Amazing Scarlet Spider #1-2 (Nov.-Dec. 1995), featuring Ben Reilly. The series picked up again with #407 (Jan. 1996), with Tom DeFalco returning as writer. Bagley completed his 5½-year run by September 1996. A succession of artists, including Ron Garney, Steve Skroce, Joe Bennett, and Rafael Kayanan, penciled the book until the final issue, #441 (Nov. 1998), after which Marvel rebooted the title with vol. 2, #1 (Jan. 1999).

Relaunch and the 2000s

Marvel began The Amazing Spider-Man anew with vol. 2, #1 (Jan. 1999).[86][87] Howard Mackie wrote the first 29 issues. The relaunch included the Sandman being regressed to his criminal ways and the "death" of Mary Jane, which was ultimately reversed. Other elements included the introduction of a new Spider-Woman (who was spun off into her own short-lived series) and references to John Byrne's Spider-Man: Chapter One, which launched at the same time as the reboot. Mackie's run ended with The Amazing Spider-Man Annual 2001, which saw the return of Mary Jane, who then left Parker upon reuniting with him.

With #30 (June 2001), J. Michael Straczynski took over as writer[88] and oversaw additional storylines — most notably his lengthy "Spider-Totem" arc, which raised the issue of whether Spider-Man's powers were magic-based, rather than as the result of a radioactive spider's bite. Additionally, Straczynski resurrected the plot point of Aunt May discovering her nephew was Spider-Man,[89] and returned Mary Jane, with the couple reuniting in The Amazing Spider-Man #50. Straczynski gave Spider-Man a new profession, having Parker teach at his former high school.

Issue #30 began a dual numbering system, with the original series numbering (#471) returned and placed alongside the volume-two number on the cover. Other longtime, rebooted Marvel Comics titles, including Fantastic Four, likewise were given the dual numbering around this time. In October 2000, John Romita, Jr. succeeded John Byrne as artist. After vol. 2, #58 (Nov. 2003), the title reverted completely to its original numbering for #500 (Dec. 2003).[86] Mike Deodato, Jr. penciled the series from mid-2004 until 2006.

That year Peter Parker revealed his Spider-Man identity on live television in the company-crossover storyline "Civil War",[90][91] in which the superhero community is split over whether to conform to the federal government's new Superhuman Registration Act. This knowledge was erased from the world with the event of the four-part, crossover story arc, "One More Day", written partially by J. Michael Straczynski and illustrated by Joe Quesada, running through The Amazing Spider-Man #544-545 (Nov.-Dec. 2007), Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man #24 (Nov. 2007) and The Sensational Spider-Man #41 (Dec. 2007), the final issues of those two titles. Here, the demon Mephisto makes a Faustian bargain with Parker and Mary Jane, offering to save Parker's dying Aunt May if the couple will allow their marriage to have never existed, rewriting that portion of their pasts. This story arc marked the end of Straczynski's tenure as writer.

Following this, Marvel made The Amazing Spider-Man the company's sole Spider-Man title, increasing its frequency of publication to three issues monthly, and inaugurating the series with a sequence of "back to basics" story arcs under the banner of "Brand New Day". Parker now exists in a changed world where he and Mary Jane had never married, and Parker has no memory of being married to her, with domino effect differences in their immediate world. The most notable of these revisions to Spider-Man continuity are the return of Harry Osborn, whose death in The Spectacular Spider-Man #200 (May 1993) is erased; and the reestablishment of Spider-Man's secret identity, with no one except Mary Jane able to recall that Parker is Spider-Man (although he soon reveals his secret identity to the New Avengers and the Fantastic Four). The alternating regular writers were initially Dan Slott, Bob Gale, Marc Guggenheim, Fred Van Lente, and Zeb Wells, joined by a rotation of artists that included Chris Bachalo, Phil Jimenez, Mike McKone, John Romita, Jr. and Marcos Martín. Joe Kelly, Mark Waid and Roger Stern later joined the writing team and Barry Kitson the artist roster. Waid's work on the series included a meeting between Spider-Man and Stephen Colbert in The Amazing Spider-Man #573 (Dec. 2008).[92] Issue #583 (March 2009) included a back-up story in which Spider-Man meets President Barack Obama.[93][94]

2010s and temporary end of publication

Mark Waid scripted the opening of the "The Gauntlet" storyline in issue #612 (Jan. 2010).[95] With issue #648 (Jan. 2011), the series became a twice-monthly title with Dan Slott as sole writer.[96][97] Eight additional pages were added per issue. This publishing format lasted until issue #700, which concluded the "Dying Wish" storyline, in which Parker and Doctor Octopus swapped bodies, and the latter taking on the mantle of Spider-Man when Parker apparently died in Doctor Octopus' body. The Amazing Spider-Man ended with this issue, with the story continuing in the new series The Superior Spider-Man.[98][99] In December 2013, the series returned for five issues, numbered 700.1 through 700.5, with the first two written by David Morrell and drawn by Klaus Janson.[100]

2014 relaunch

In January 2014, Marvel confirmed that The Amazing Spider-Man would be relaunched on April 30, 2014, starting from issue #1, with Peter Parker once again as Spider-Man.[101]

References

- ^ Morse, Ben (October 10, 2012). "Marvel NOW! Q&A: Superior Spider-Man". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b DeFalco, Tom; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). "1960s". Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. Dorling Kindersley. p. 87. ISBN 978-0756641238.

Deciding that his new character would have spider-like powers, [Stan] Lee commissioned Jack Kirby to work on the first story. Unfortunately, Kirby's version of Spider-Man's alter ego Peter Parker proved too heroic, handsome, and muscular for Lee's everyman hero. Lee turned to Steve Ditko, the regular artist on Amazing Adult Fantasy, who designed a skinny, awkward teenager with glasses.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Amazing Spider-Man at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ The Amazing Spider-Man vol. 2 at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ The Amazing Spider-Man (continuation of volume 1) at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 91: "Thanks to a flood of fan mail, Spider-Man was awarded his own title six months after his first appearance. Amazing Spider-Man began as a bimonthly title, but was quickly promoted to a monthly."

- ^ a b DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 91

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko Steve (i). "Spider-Man" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 1 (March 1963).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 92: "Introduced in the lead story of The Amazing Spider-Man #2 and created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, the Vulture was the first in a long line of animal-inspired super-villains that were destined to battle everyone's favorite web-slinger."

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Duel to the Death with the Vulture!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 2 (May 1963).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 93: "Dr. Octopus shared many traits with Peter Parker. They were both shy, both interested in science, and both had trouble relating to women...Otto Octavius even looked like a grown up Peter Parker. Lee and Ditko intended Otto to be the man Peter might have become if he hadn't been raised with a sense of responsiblity"

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Spider-Man Versus Doctor Octopus" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 3 (July 1963).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Nothing Can Stop...The Sandman!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 4 (September 1963).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 95

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Face-to-Face With...the Lizard!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 6 (November 1963).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 98

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Man Called Electro!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 9 (February 1964).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Menace of... Mysterio!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 13 (June 1964).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 101: "When the Green Goblin soared into the webhead's life, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko didn't bother to discuss his secret identity. They just knew they had an interesting character to add to Spider-Man's growing gallery of villains."

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Grotesque Adventure of the Green Goblin!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 14 (July 1964).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "Kraven the Hunter!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 15 (August 1964).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The End of Spider-Man!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 18 (November 1964).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Coming of the Scorpion!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 20 (January 1965).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "The Menace of the Molten Man!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 28 (September 1965).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 111: "Gwen Stacy, the platinum blonde ex-beauty queen of Standard High, met Peter Parker on his first day in college in this issue."

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Ditko, Steve (p), Ditko, Steve (i). "If This Be My Destiny!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 31 (December 1965).

- ^ Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. Harry N. Abrams. p. 129. ISBN 9780810938212.

- ^ David, Peter; Greenberger, Robert (2010). The Spider-Man Vault: A Museum-in-a-Book with Rare Collectibles Spun from Marvel's Web. Running Press. p. 29. ISBN 0762437723.

- ^ Saffel, Steve (2007). "A Legend Is Born". Spider-Man the Icon: The Life and Times of a Pop Culture Phenomenon. Titan Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84576-324-4.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. Dorling Kindersley. p. 34. ISBN 978-0756692360.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greenberger, Robert, ed. (December 2001). 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time. Marvel Comics. p. 67.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 117: "To this day, no one really knows why Ditko quit. Bullpen sources reported he was unhappy with the way Lee scripted some of his plots, using a tongue-in-cheek approach to stories Ditko wanted handled seriously."

- ^ "Confidential Videotaped Deposition of John V. Romita". Garden City, New York: United States District Court, Southern District of New York: "Marvel Worldwide, Inc., et al., vs. Lisa R. Kirby, et al.". October 21, 2010. p. 45.

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 119: "After teasing the readers for more than two years, Stan Lee finally allowed Peter Parker to meet Mary Jane Watson."

- ^ David and Greenberger, p. 38

- ^ Saffel "A Legend is Born", p. 27

- ^ Manning "1960s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 46: "Stan Lee tackled the issues of the day again when, with artists John Romita and Jim Mooney, he dealt with social unrest at Empire State University."

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 122: "Stan Lee wanted to create a new kind of crime boss. Someone who treated crime as if it were a business...He pitched this idea to artist John Romita and it was Wilson Fisk who emerged in The Amazing Spider-Man #50."

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Esposito, Mike (i). "Spider-Man No More!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 50 (July 1967).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 119: "The first original super-villain produced by the new Spider-Man team of Stan Lee and John Romita was the Rhino."

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Esposito, Mike (i). "The Horns of the Rhino!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 41 (October 1966).

- ^ DeFalco "1960s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 121

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Romita, Sr., John (i). "The Sinister Shocker!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 46 (March 1967).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Buscema, John (p), Mooney, Jim (i). "The Night of the Prowler!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 78 (November 1969).

- ^ Lee, Stan (w), Romita, Sr., John (p), Esposito, Mike (i). "The Schemer!" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 83 (April 1970).

- ^ Sanderson, Peter "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 155: "Marvel Team-Up #1 inaugurated a new series in which Spider-Man teamed with a different hero in each issue.""

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 177: "Spider-Man already starred in two monthly series: The Amazing Spider-Man and Marvel Team-Up. Now Marvel added a third, Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man, initially written by Gerry Conway with art by Sal Buscema and Mike Esposito."

- ^ Giant-Size Spider-Man at the Grand Comics Diiiuatabase

- ^ Spidey Super Stories at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Goodgion, Laurel F. (1978). Young Adult Literature in the Seventies: A Selection of Readings. The Scarecrow Press. p. 348. ISBN 0-8108-1134-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 55: "Captain George Stacy had always believed in Spider-Man and had given him the benefit of the doubt whenever possible. So in Spider-Man's world, there was a good chance that he would be destined to die."

- ^ a b Gil Kane's run on The Amazing Spider-Man at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Saffel "Bucking the Establishment, Marvel Style", p. 60: "The stories received widespread mainstream publicity, and Marvel was hailed for sticking to its guns."

- ^ Daniels, pp. 152 and 154: "As a result of Marvel's successful stand, the Comics Code had begun to look just a little foolish. Some of its more ridiculous restrictions were abandoned because of Lee's decision."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 59: "In the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man to be written by someone other than Stan Lee, Roy Thomas was faced with the mammoth task of not only filling the vaunted writer's shoes but also solving the bizarre cliffhanger from the last issue."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 61: "Stan Lee had returned to The Amazing Spider-Man for a handful of issues after leaving following issue #100 (September 1971). With issue #110. Lee once again departed the title into which he had infused so much of his own personality over his near 10-year stint as regular writer."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 62: "[The Amazing Spider-Man #111] marked the dawning of a new era: writer Gerry Conway came on board as Stan Lee's replacement. Alongside artist John Romita, Conway started his run by picking up where Lee left off."

- ^ Sanderson "1970s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 159: "In June [1973], Marvel embarked on a story that would have far-reaching effects. The Amazing Spider-Man artist John Romita, Sr. suggested killing off Spider-Man's beloved Gwen Stacy in order to shake up the book's status quo."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 68: "This story by writer Gerry Conway and penciler Gil Kane would go down in history as one of the most memorable events of Spider-Man's life."

- ^ David and Greenberger p. 49: "The idea of beloved supporting characters meeting their deaths may be standard operating procedure now but in 1973 it was unprecedented...Gwen's death took villainy and victimhood to an entirely new level."

- ^ Saffel "Death and the Spider", p. 65: "Death struck again, with repercussions that would ripple through comics from that day forward."

- ^ Ross Andru's run on The Amazing Spider-Man at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 72: "Writer Gerry Conway and artist Ross Andru introduced two major new characters to Spider-Man's world and the Marvel Universe in this self-contained issue. Not only would the vigilante known as the Punisher go on to be one of the most important and iconic Marvel creations of the 1970s, but his instigator, the Jackal, would become the next big threat in Spider-Man's life."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 85: "To signify the start of this new era Spider-Man's new regular chronicler writer Len Wein would come onboard with this issue."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 103: "As new regular writer Marv Wolfman took over the scripting duties from Len Wein and partnered with artist Ross Andru, Peter Parker decided to make a dramatic change in his personal life."

- ^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 107: "Spider-Man wasn't exactly sure what to think about his luck when he met a beautiful new thief on the prowl named the Black Cat, courtesy of a story by writer Marv Wolfman and artist Keith Pollard."

- ^ Martini, Frank (December 2013). "Marv Wolfman's Bicentennial Battles". Back Issue (69). TwoMorrows Publishing: 44–47.

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 115: "Acclaimed writer Denny O'Neil had returned to Marvel and...took over as the regular writer on The Amazing Spider-Man from issue #207 (August [1980]) until the end of 1981."

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 114: "Writer Denny O'Neil and artist Frank Miller...used their considerable talents in this rare collaboration that teamed two other legends - Dr. Strange and Spider-Man."

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 120: "Writer Denny O'Neil teamed with artist Frank Miller to concoct a Spider-Man annual that played to both their strengths. Miller and O'Neil seemed to flourish in the gritty world of street crime so tackling a Spider/Punisher fight was a natural choice."

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 126: "Writer Roger Stern moved from the helm of Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man to sit behind the wheel as the new regular writer of The Amazing Spider-Man with this issue."

- ^ a b David and Greenberger, pp. 68-69: "Writer Roger Stern is primarily remembered for two major contributions to the world of Peter Parker. One was a short piece entitled 'The Kid Who Collects Spider-Man'...[his] other major contribution was the introduction of the Hobgoblin."

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 133: "Writer Roger Stern and artists John Romita, Jr. and John Romita, Sr. introduced a new - and frighteningly sane - version of the [Green Goblin] concept with the debut of the Hobgoblin."

- ^ Cronin, Brian (May 10, 2010). "The Greatest Roger Stern Stories Ever Told!". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

Stern and guest-artist Ron Frenz tell the heartfelt tale of a little boy who might be Spider-Man's biggest fan. Spidey visits the boy and has a nice talk with him (and naturally, there is a twist to the tale).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Priest, Christopher J. (May 2002). "Oswald: Why I Never Discuss Spider-Man". DigitalPriest.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

The catalyst for my demise was my firing Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz off of Amazing Spider-Man.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ DeFalco "1980s" in Gilbert (2008), p. 231: "The six-issue story arc...ran through all the Spider-Man titles for two months."

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 169: "In this landmark installment [issue #298], one of the most popular characters in the wall-crawler's history would begin to step into the spotlight courtesy of one of the most popular artists to ever draw the web-slinger."

- ^ Singh, Karanvir (July 30, 2012). "Amazing Spider-Man #328 Cover Art by Todd McFarlane sells for a record $657,250". BornRich.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Saffel "Taking Stock: The 1990s" pp. 185-186

- ^ Mark Bagley's run on The Amazing Spider-Man at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Cowsill, Alan "1990s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 197: "Artist Mark Bagley's era of The Amazing Spider-Man hit its stride as Carnage revealed the true face of his evil. Carnage was a symbiotic offspring produced when Venom bonded to psychopath Cletus Kasady."

- ^ Cowsill "1990s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 199

- ^ Cowsill "1990s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 203

- ^ "Comic Printing Errors". Gemstone Publishing. Archived from the original on April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ David, Peter (July 3, 1998). "The Illusion of Change". Comics Buyer's Guide. Archived from the original on April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

[Marvel] came up with the Spider-Man clone. Free of any of the baggage the character had accrued since the death of Gwen, he was supposed to reconnect the audience to Spider-Man. The problem is, all writing is a magic trick. You try to pull fast ones on the audience so that they don't look too closely. In this case, it was easy to cast Marvel as Bullwinkle, announcing his intention to pull a rabbit out of his hat, and the fans as a skeptical Rocky loudly proclaiming, 'That trick never works!' And it didn't. Because fans don't like to be treated as if they're stupid.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hunt, James (August 5, 2008). "The Marvel 500s: How Many Are There?". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cowsill "1990s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 246: "This new series heralded a fresh start for the web-slinger's adventures."

- ^ Cowsill "2000s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 262: "J. Michael Straczynski and artist John Romita, Jr. took the helm in this issue to create some of the best Spider-Man stories of the decade."

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (w), Romita, Jr., John (p), Hanna, Scott (i). "Interlude" The Amazing Spider-Man, vol. 2, no. 37 (January 2002).

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (w), Garney, Ron (p), Reinhold, Bill (i). "The War At Home" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 532 (July 2006).

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (w), Garney, Ron (p), Reinhold, Bill (i). "The Night the War Came Home Part Two" The Amazing Spider-Man, no. 533 (August 2006).

- ^ Cowsill "2000s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 316: "The issue [#573] also saw TV star Stephen Colbert team up with Spider-Man in a back-up story written by Mark Waid and drawn by Patrick Olliffe."

- ^ Cowsill "2000s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 319: "With President Obama about to be inaugurated, Marvel produced a special variant issue of The Amazing Spider-Man complete with...a five-page back-up strip co-starring the President, written by Zeb Wells and drawn by Todd Nauck."

- ^ Colton, David (January 7, 2009). "Obama, Spider-Man on the same comic-book page". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cowsill "2010s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 327: "Written by Mark Waid and drawn by Paul Azaceta, the two-part opening mixed the real-world drama of the economic meltdown with some Spidey action."

- ^ Cowsill "2010s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 334: "Spidey's adventures were about to take an exciting new direction as Dan Slott became the title's sole writer."

- ^ Wigler, Josh (July 25, 2010). "CCI: The Marvel: Spider-Man Panel". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Archive requires scrolldown - ^ Moore, Matt (December 26, 2012). "Marvel's Peter Parker in Perilous Predicament". Associated Press via ABC News. Archived from the original on December 29, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hanks, Henry (December 31, 2012). "Events in landmark Spider-Man issue have fans in a frenzy". CNN. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Morris, Steve (September 12, 2013). "Marvel in December: Welcome Back, Peter Parker, Bye Kaine". The Beat. Archived from the original on November 25, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; November 26, 2013 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sacks, Ethan (January 12, 2014). "Exclusive: Peter Parker to return from death in 'Amazing Spider-Man' #1 this April". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

External links

- The Amazing Spider-Man at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- The Amazing Spider-Man volume 2 at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- The Amazing Spider-Man comic book sales figures from 1966–present at The Comics Chronicles

- Spider-Man at Marvel Comics wikia

- The Amazing Spider-Man cover gallery

- Spiderman Videos