Amoeba: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}} |

Deuterostome (talk | contribs) →Amoebae in multicellular organisms: Slime molds and animals: Edited for style and content |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Some multicellular organisms have amoeboid cells only in certain phases of life, or use amoeboid cells for certain specialized functions. In humans and other animals, [[white blood cells]] use amoeboid movement to pursue and engulf invading organisms, such as bacteria.<ref>Friedl, Peter, Stefan Borgmann, and Eva-B. Bröcker. "Amoeboid leukocyte crawling through extracellular matrix: lessons from the Dictyostelium paradigm of cell movement." Journal of leukocyte biology 70.4 (2001): 491-509.</ref> |

Some multicellular organisms have amoeboid cells only in certain phases of life, or use amoeboid cells for certain specialized functions. In humans and other animals, [[white blood cells]] use amoeboid movement to pursue and engulf invading organisms, such as bacteria.<ref>Friedl, Peter, Stefan Borgmann, and Eva-B. Bröcker. "Amoeboid leukocyte crawling through extracellular matrix: lessons from the Dictyostelium paradigm of cell movement." Journal of leukocyte biology 70.4 (2001): 491-509.</ref> |

||

Amoeboid stages also occur in fungus-like protists, the so-called [[slime mold]]s. Both the plasmodial slime molds, currently classified in the taxon [[Myxogastria]]), and the cellular slime molds of the groups [[Acrasida]] and [[Dictyosteliida]]), use amoeboid movement in their feeding stage. The cells of the former form a giant [[multinucleate]] amoeboid "supercell", or [[syncitium]], while the cells of the latter live separately until food runs out, at which time the amoebae aggregate to form a colony that functions as a unit.{{Cn|date=September 2014}} |

|||

===Classification=== |

===Classification=== |

||

Revision as of 18:21, 13 September 2014

An amoeba (also, ameba, amœba, or amoeboid) is a type of cell or organism which has the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and retracting pseudopods.[1] Amoebae do not form a single taxonomic group, but are found in every major lineage of eukaryotic organisms (domain Eukaryota). Amoeoboid cells occur not only among protists, but also fungi, algae and animals.[2][3][4]

Most references to "amoeba," in both scientific and general usage refer to amoebae in general rather than to the genus Amoeba. Among microbiologists, the terms "amoeboid" and "amoebae" are often used interchangeably for any organism that exhibits amoeboid movement.[5] [6]

Shape and structure

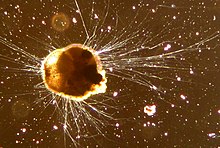

Amoebae move and feed by using pseudopods, which are bulges of cytoplasm formed by the coordinated action of microfilaments pushing out the plasma membrane which surrounds the cell.[7] Microfilaments make up at least 50% of the cytoskeleton, the remainder being composed of stiffer intermediate filaments and microtubules. These are not used in amoeboid movement, but are stiff structures on which organelles are supported or along which they move.[citation needed]

Free-living amoebae may be "testate" (enclosed within a hard shell), or "naked" (lacking any hard covering). The shells of testate amoebae may be composed of a variety of materials, including calcium, silica, proteins such as chitin, or agglutinations of found materials like small particles of sand and the frustules of diatoms.[8]

Amoebae breathe using their entire cell membrane, which is constantly immersed in water. [citation needed] In free-living amoebae, excess water can cross into the cytosol by osmosis. To regulate osmotic pressure, amoebae may have a contractile vacuole to expel excess water.[citation needed]

The food sources of amoebae vary. Some amoebae consume bacteria and other protists. Some are detritivores and eat dead organic material. Amoebae take in particles of food by phagocytosis, extending a pair of pseudopods to engulf nutrients. As the pseudopds fuse, a food vacuole is created which then fuses with a lysosome to add digestive chemicals. Undigested food is expelled at the cell membrane.[citation needed]

Amoebae in multicellular organisms: Slime molds and animals

Some multicellular organisms have amoeboid cells only in certain phases of life, or use amoeboid cells for certain specialized functions. In humans and other animals, white blood cells use amoeboid movement to pursue and engulf invading organisms, such as bacteria.[9]

Amoeboid stages also occur in fungus-like protists, the so-called slime molds. Both the plasmodial slime molds, currently classified in the taxon Myxogastria), and the cellular slime molds of the groups Acrasida and Dictyosteliida), use amoeboid movement in their feeding stage. The cells of the former form a giant multinucleate amoeboid "supercell", or syncitium, while the cells of the latter live separately until food runs out, at which time the amoebae aggregate to form a colony that functions as a unit.[citation needed]

Classification

The amoebae are no longer classified in one taxonomic group, since a taxon containing all of the organsms traditionally categorized as "amoebae" would be a polyphyletic grouping, including many species that are not closely related.

In older classification systems, most amoebae were grouped together in the class or subphylum Sarcodina. Within the Sarcodina, amoebae were divided into morphological categories, on the basis of the form and structure of their pseudopods. Amoebae with pseudopods supported by regular arrays of microtubules were called actinopods, whereas those with unsupported pseudopods were designated rhizopods. The Rhizopoda were further subdivided into lobose, filose, and reticulose amoebae.

When molecular (genetic) confirmed that Sarcodina was a polyphyletic group, it was abandoned and the amoebae were scattered among many other groups. The majority of traditional "Sarcodines" are now placed in two eukaryote supergroups: Amoebozoa and Rhizaria. The rest have been distributed among the excavates, opisthokonts, and stramenopiles. Some, like the Centrohelida, have yet to be placed in any supergroup.[10]

Whereas older classifications were based mainly on morphology, modern schemes are based upon cladistics. Phylogenetic analyses place amoeboid genera into the following groups :

| Grouping | Genera | Morphology |

|---|---|---|

| Amoebozoa |

|

|

| Rhizaria |

| |

| Excavata |

| |

| Chromalveolate | Heterokont: Hyalodiscus, Labyrinthula Alveolata: Pfiesteria |

|

| Nucleariid | Micronuclearia, Nuclearia |

|

| Ungrouped/ unknown |

Adelphamoeba, Astramoeba, Cashia, Dinamoeba, Flagellipodium, Flamella, Gibbodiscus, Gocevia, Hollandella, Iodamoeba, Malamoeba, Nollandia, Oscillosignum, Paragocevia, Parvamoeba, Pernina, Pontifex, Protonaegleria, Pseudomastigamoeba, Rugipes, Striamoeba, Striolatus, Subulamoeba, Theratromyxa, Trienamoeba, Trimastigamoeba, Vampyrellium |

Pathogenic interactions with other organisms

Some amoebae can infect other organisms pathogenically, causing disease:

- Entamoeba histolytica is the cause of amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery.

- Naegleria fowleri (the "brain-eating amoeba") is a fresh-water-native species that can be fatal to humans if introduced through the nose.

- Acanthamoeba can cause amoebic keratitis and encephalitis in humans.

- Balamuthia mandrillaris is the cause of (often fatal) granulomatous amoebic meningoencephalitis

References

- ^ SIngleton, Paul (2006). Dictionary of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, 3rd Edition, revised. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-470-03545-0 (PB).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ http://tolweb.org/notes/?note_id=51

- ^ http://www.bms.ed.ac.uk/research/others/smaciver/amoebae.htm

- ^ http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/mag/wimsmall/sundr.html

- ^ Marée, Athanasius FM, and Paulien Hogeweg. "How amoeboids self-organize into a fruiting body: multicellular coordination in Dictyostelium discoideum." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98.7 (2001): 3879-3883.

- ^ Mackerras, M. J., and Q. N. Ercole. "Observations on the action of paludrine on malarial parasites." Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 41.3 (1947): 365-376.

- ^ Alberts et al. Eds. (2007). Molecular Biology of the Cell 5th Edition. New York: Garland Science. p. 1037. ISBN 9780815341055.

- ^ Ogden, C. G. (1980). An Atlas of Freshwater Testate Amoeba. Oxford, London, Glasgow: Oxford University Press, for British Museum (Natural History). pp. 1–5. ISBN 0198585020.

- ^ Friedl, Peter, Stefan Borgmann, and Eva-B. Bröcker. "Amoeboid leukocyte crawling through extracellular matrix: lessons from the Dictyostelium paradigm of cell movement." Journal of leukocyte biology 70.4 (2001): 491-509.

- ^ Jan Pawlowski: The twilight of Sarcodina: a molecular perspective on the polyphyletic origin of amoeboid protists. Protistology, Band 5, 2008, S. 281–302. (pdf, 570 kB)

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19121603, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19121603instead.

External links

- The Amoebae website brings together information from published sources.

- Amoebas are more than just blobs

- Sun Animacules and Amoebas

- Molecular Expressions Digital Video Gallery: Pond Life - Amoeba (Protozoa) Some good, informative Amoeba videos.

- Amoebae: Protists Which Move and Feed Using Pseudopodia at the Tree of Life web project

- Microworld: world of amoeboid organisms - Arcella.nl