Second Italo-Ethiopian War: Difference between revisions

KolbertBot (talk | contribs) m Bot: HTTP→HTTPS |

A protest for Etopian war |

||

| Line 263: | Line 263: | ||

The treaty signed in Paris by the [[Italian Republic]] (''Repubblica Italiana'') and the [[allies of World War II|victorious powers]] of World War II on 10 February, included formal Italian recognition of Ethiopian independence and an agreement to pay $25,000,000 in [[Paris Peace Treaties, 1947|reparations]]. Ethiopia became independent again and Selassie was restored as its leader. Ethiopia presented bill to the Economic Commission for Italy of £184,746,023 for damages inflicted during the course of the Italian occupation. Claimed were the loss of 2,000 churches, 525,000 houses and the slaughter and/or confiscation of six million beef cattle, seven million sheep and goats, one million horses and mules and 700,000 camels.{{sfn|Barker|1971|p=159}} The Ethiopians recorded 275,000 combatants killed in action, 78,500 patriots killed during the occupation (1936–1941), 17,800 civilians killed by bombing and 30,000 in the February 1937 massacre, 35,000 people died in concentration camps, 24,000 patriots executed by Summary Courts, 300,000 persons died of privation due to the destruction of their villages, amounting to 760,300 human deaths.{{sfn|Barker|1971|p=159}} The Italians disputed this huge amount, arguing that real Ethiopian casualties were half the Ethiopian claim.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat3.htm#Eth35|title=WAR STATS REDIRECT|publisher=|accessdate=24 May 2015}}</ref> |

The treaty signed in Paris by the [[Italian Republic]] (''Repubblica Italiana'') and the [[allies of World War II|victorious powers]] of World War II on 10 February, included formal Italian recognition of Ethiopian independence and an agreement to pay $25,000,000 in [[Paris Peace Treaties, 1947|reparations]]. Ethiopia became independent again and Selassie was restored as its leader. Ethiopia presented bill to the Economic Commission for Italy of £184,746,023 for damages inflicted during the course of the Italian occupation. Claimed were the loss of 2,000 churches, 525,000 houses and the slaughter and/or confiscation of six million beef cattle, seven million sheep and goats, one million horses and mules and 700,000 camels.{{sfn|Barker|1971|p=159}} The Ethiopians recorded 275,000 combatants killed in action, 78,500 patriots killed during the occupation (1936–1941), 17,800 civilians killed by bombing and 30,000 in the February 1937 massacre, 35,000 people died in concentration camps, 24,000 patriots executed by Summary Courts, 300,000 persons died of privation due to the destruction of their villages, amounting to 760,300 human deaths.{{sfn|Barker|1971|p=159}} The Italians disputed this huge amount, arguing that real Ethiopian casualties were half the Ethiopian claim.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat3.htm#Eth35|title=WAR STATS REDIRECT|publisher=|accessdate=24 May 2015}}</ref> |

||

==== Protest by Tagore in 1937 ==== |

|||

Famous Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore who was awarded Nobel Prize in literature protested this invasion. He wrote a poem named '''[https://animikha.wordpress.com/2015/04/10/%E0%A6%AA%E0%A6%A4%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%AA%E0%A7%81%E0%A6%9F%E0%A6%83-%E0%A6%B7%E0%A7%8B%E0%A6%B2%E0%A7%8B-%E0%A6%86%E0%A6%AB%E0%A7%8D%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%BF%E0%A6%95%E0%A6%BE-potroput-verse-16-af/ Africa]''' in Bengali on 10th February 1937. Later it was [http://www.markedbyteachers.com/international-baccalaureate/world-literature/n-the-poem-africa-explore-how-tagore-conveys-the-changes-which-have-occurred-in-africa-due-to-the-influence-of-western-imperialism.html translated in English] by William Radice. He criticized the colonization of Africa. He was against imperialism. He was deeply sorrowed for the destruction of African culture by the Western people. In his poem he prayed for peace in Africa. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 11:08, 12 September 2017

| Second Italo-Ethiopian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Interwar Period | |||||||||

Italian artillery in Tembien, Ethiopia, in 1936 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Material support: | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Approx. 500,000 combatants (Approx. 100,000 mobilised) Approx. 595 aircraft[2] Approx. 795 tanks[2] |

c. 800,000 combatants (c. 330,000 mobilised) 13 aircraft [citation needed] 4 tanks and 7 armoured cars | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

10,000 killed (mostly African auxiliaries)1 (est. May 1936)[3] 44,000 wounded (est. May 1936)[4] 9,555 killed2 (est. 1936–1940)[5] 144,000 sick and wounded (est. 1936–1940)[6] |

c. 775,000 killed or wounded[a] 7% of Ethiopia's population killed in War Crimes against civilians or several hundreds of thousands[8] | ||||||||

|

1Official pro-Fascist Italian figures are around 3,000, which Alberto Sbacchi considers deflated.[3] | |||||||||

| Events leading to World War II |

|---|

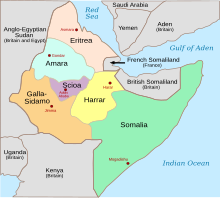

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a colonial war that started on 3 October 1935, and ended on 5 May 1936. The war was fought between the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy and the armed forces of the Ethiopian Empire (also known at the time as Abyssinia). The war resulted in the military occupation of Ethiopia.

Politically, like the Mukden Incident in 1931 (the Japanese annexation of three Chinese provinces), the Abyssinia Crisis in 1935 is often seen as a clear demonstration of the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations. Italy and Ethiopia were member nations and yet the League was unable to control Italy or to protect Ethiopia when Italy clearly violated Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations.

The Italian victory in the war coincided with the zenith of the international popularity of dictator Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime, during which colonialist leaders praised Mussolini for his actions.[9] The victory also brought Mussolini unprecedented popularity within Italy. Shortly after the war, Ethiopia was consolidated with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland into Italian East Africa. Mussolini's international popularity decreased as he endorsed the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, beginning a political tilt toward Germany that ultimately destroyed Mussolini and the Fascist regime in Italy in World War II.[10]

Background

Abyssinia Crisis

The Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928 stated that the border between Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia was twenty-one leagues parallel to the Benadir coast (approximately 118.3 kilometres [73.5 miles]). In 1930, Italy built a fort at the Welwel oasis (also Walwal, Italian: Ual-Ual) in the Ogaden and garrisoned it with Somali Ascari (dubats) (irregular frontier troops commanded by Italian officers). The fort at Welwel was well beyond the twenty-one league limit and inside Ethiopian territory. In November 1934, Ethiopian territorial troops, escorting the Anglo-Ethiopian boundary commission, protested against Italy's incursion. The British members of the commission soon withdrew to avoid embarrassing Italy but Italian and Ethiopian troops remained encamped close by.

Wal Wal Incident

In early December 1934, the tensions on both sides erupted into what was known as the Wal Wal Incident. The resultant clash left approximately 110 Ethiopians and between 30 and 50 Italians and Somalis dead and led to the "Abyssinia Crisis" at the League of Nations.[b] On 4 September 1935, the League of Nations exonerated both parties for the Wal Wal Incident.[13]

Ethiopian isolation

Britain and France preferred Italy as an ally against Germany, did not take strong steps to discourage an Italian military buildup on the borders of Ethiopia in Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. On 7 January 1935, a Franco-Italian Agreement was made giving Italy essentially a free hand in Africa in return for Italian co-operation.[14] In April, Italy was further emboldened by participation in the Stresa Front, an agreement to curb further German violations of the Treaty of Versailles.[15] In June, non-interference was further assured by a political rift that had developed between the United Kingdom and France following the Anglo-German Naval Agreement.[16] A last possible foreign ally of Ethiopia to fall away was Japan, which had served as a model to some Ethiopian intellectuals; the Japanese ambassador to Italy, Dr. Sugimura Yotaro, on 16 July assured Mussolini that his country held no political interests in Ethiopia and would stay neutral in the coming war. His comments stirred up a furore inside Japan, where there had been popular affinity for the African Empire. Despite popular opinion, when the Ethiopians approached Japan for help on 2 August, they were refused, even a modest request for the Japanese government to officially state its support for Ethiopia in the coming conflict was denied.[17]

Hoare–Laval Pact

In early December 1935, the Hoare–Laval Pact was proposed by Britain and France. Under this pact, Italy would gain the best parts of Ogaden, Tigray and economic influence over all the southern part of Abyssinia. Abyssinia would have a guaranteed corridor to the sea at the port of Assab; the corridor was a poor one and known as a "corridor for camels".[18] Mussolini was ready to agree but he waited some days to make his opinion public. On 13 December, details of the pact were leaked by a French newspaper and denounced as a sell-out of the Abyssinians. The British government disassociated itself from the pact and the British and the French representatives associated with it were forced to resign.

Prelude

Ethiopian army

With war appearing inevitable, the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, ordered a general mobilisation of the Army of the Ethiopian Empire.

All men and boys able to carry a spear go to Addis Ababa. Every married man will bring his wife to cook and wash for him. Every unmarried man will bring any unmarried woman he can find to cook and wash for him. Women with babies, the blind, and those too aged and infirm to carry a spear are excused. Anyone found at home after receiving this order will be hanged.[19][20]

Selassie's army consisted of around 500,000 men, some of whom were armed with spears and bows; other soldiers carried more modern weapons, including rifles but many of these were pre-1900 equipments and obsolete.[21] According to Italian estimates, on the eve of hostilities, the Ethiopians had an army of 350,000–760,000 men. Only about 25 percent of the army had any military training and the men were armed with a motley of 400,000 rifles of every type and in every condition.[22] The Ethiopian armies had about 234 antiquated pieces of artillery mounted on rigid gun carriages, as well as a dozen 3.7 cm PaK 35/36 anti-tank guns. The army had about 800 light Colt and Hotchkiss machine-guns and 250 heavy Vickers and Hotchkiss machine guns, about 100 .303-inch Vickers guns on AA mounts, 48 20 mm Oerlikon S anti-aircraft guns and some recently purchased Canon de 75 CA modèle 1940 Schneider 75 mm guns. The arms embargo imposed on the belligerents by France and Britain disproportionately affected Ethiopia, which lacked the manufacturing industry to produce its own weapons.[1] The Ethiopian army had some 300 trucks, seven Ford A-based armoured cars and four World War I era Fiat 3000 tanks.[22]

The best Ethiopian units were the Emperor's "Kebur Zabagna" (Imperial Guard), who were well-trained and better equipped than the other Ethiopian troops. The Imperial Guard wore a distinctive greenish-khaki uniform of the Belgian Army, which stood out from the white cotton cloak (shamma) worn by most Ethiopian fighters and which proved to be an excellent target.[22] The skills of the Rases, the generals of the Ethiopian armies, were reported to rate from relatively good to incompetent. The serviceable portion of the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force under the command of the French Andre Maillet, included three obsolete Potez 25 biplanes.[23] A few transport aircraft had been acquired between 1934 and 1935 for ambulance work but the air force consisted of 13 aircraft and four pilots at the outbreak of the war.[24] After Italian objections to an Anschluss with Austria, Germany sent three aeroplanes, 10,000 Mauser rifles and 10 million rounds of ammunition to the Ethiopians.[1]

Fifty foreign mercenaries joined the Ethiopian forces, including French pilots like Pierre Corriger, an official Swedish military mission under Captain Viking Tamm, the White Russian Feodor Konovalov and the Czechoslovak writer Adolf Parlesak. Several Austrian Nazis, a team of Belgian Fascists and Cuban mercenary Alejandro del Valle also fought for Haile Selassie.[25] Many of these individuals were military advisers, pilots, doctors or supporters of the Ethiopian cause; fifty mercenaries fought in the Ethiopian army and another fifty people were active in the Ethiopian Red Cross or non-military activities.[26] The Italians later attributed most of the relative success achieved by the Ethiopians to foreigners or ferenghi.[27] (The Italian propaganda machine magnified the number to thousands, to explain away the Ethiopian the Christmas Offensive of late 1935.)[28][c]

-

Haile Selassie, commander of the Ethiopian army.

-

Ras Desta Damtew

-

Marcel Junod of the Red Cross (left) with Sidney Brown (centre) in Addis Ababa.

Italian East African forces

There were 400,000 Italian soldiers in Eritrea and 285,000 in Italian Somaliland with 3,300 machine guns, 275 artillery pieces, 200 tankettes and 205 aircraft. In April 1935, the reinforcement of the Royal Italian Army (Regio Esercito) and the Regia Aeronautica (Royal Air Force) in East Africa (Africa Orientale) accelerated. Eight regular, mountain and blackshirt militia infantry divisions arrived in Eritrea and four regular infantry divisions arrived in Italian Somaliland, consisting of about 685,000 soldiers and a great number of logistical and support units; the Italian force included 200 journalists.[31] The Italian force had 6,000 machine guns, 2,000 pieces of artillery, 599 tanks and 390 aircraft. The Regia Marina (Royal Navy) carried tons of ammunition, food and other supplies, with the motor vehicles to move them, while the Ethiopians had only horse-drawn carts.[2]

The Italians placed considerable reliance on their Royal Corps of Colonial Troops (RCTC, Regio Corpo Truppe Coloniali RCTC) of indigenous regiments recruited from the Italian colonies of Eritrea, Somalia, and Libya. The most effective of these Italian commanded units were the Eritrean native infantry (Ascari) who were often used as advanced troops. The Eritreans also provided cavalry and artillery units; the "Falcon Feathers" (Penne di Falco) was one prestigious and colourful Eritrean cavalry unit. Other RCTC units employed in the invasion of Ethiopia were irregular Somali frontier troops (dubats), regular Arab-Somali infantry and artillery and Libyan infantry.[32][page needed] The Italians had a variety of local semi-independent "allies", in the north, the Azebu Galla were among several groups induced to fight for the Italians. In the south, the Somali Sultan Olol Dinle commanded a personal army that advanced into the northern Ogaden with the forces of Colonel Luigi Frusci. The Sultan was motivated by his desire to take back lands that the Ethiopians had taken from him. The Italian colonial forces even included men from Yemen, across the Gulf of Aden.[33]

The Italians were reinforced by volunteers from the so-called Italiani all'estero (Italian emigres from Argentina, Uruguay and Brasil) who formed the Divisione Tevere and a special Legione Parini, that fought under Frusci near Dire Dawa.[34] On 28 March 1935, General Emilio De Bono was named as the Commander-in-Chief of all Italian armed forces in East Africa.[35] De Bono was also the Commander-in-Chief of the forces invading from Eritrea on the northern front. De Bono commanded nine divisions in the Italian I Corps, the Italian II Corps and the Eritrean Corps. General Rodolfo Graziani was Commander-in-Chief of forces invading from Italian Somaliland on the southern front. Initially he had two divisions and a variety of smaller units under his command, a mixture of Italians, Somalis, Eritreans, Libyans and others. De Bono regarded Italian Somaliland as a secondary theatre that needed primarily to defend itself and possibly aid the main front with offensive thrusts if the enemy forces there were not too large.[36] Most foreign volunteers accompanied the Ethiopians but Matthews, Herbert Lionel, a reporter, historian and author of Eyewitness in Abyssinia: With Marshal Bodoglio's forces to Addis Ababa (1937), Pedro del Valle an observer for United States Marine Corps accompanied the Italian forces.

-

Benito Mussolini, Commander of the Italian army.

Hostilities

Italian invasion

At 5:00 am on 3 October 1935, De Bono crossed the Mareb River and advanced into Ethiopia from Eritrea without a declaration of war.[37] Aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica scattered leaflets asking the population to rebel against Haile Selassie and support the "true Emperor Iyasu V". Forty-year-old Iyasu had been deposed many years earlier but was still in custody. In response to the Italian invasion, Ethiopia declared war on Italy.[38] At this point in the campaign, the lack of roads represented a serious hindrance for the Italians as they crossed into Ethiopia. On the Italian side, roads had been constructed right up to the border. On the Ethiopian side, these roads often transitioned into vaguely defined paths.[37] On 5 October the Italian I Corps took Adigrat, and by 6 October, Adwa (Adowa) was captured by the Italian II Corps. Haile Selassie had ordered Duke (Ras) Seyoum Mangasha, the Commander of the Ethiopian Army of Tigre, to withdraw a day's march away from the Mareb River. Later, the Emperor ordered Commander of the Gate (Dejazmach) Haile Selassie Gugsa, also in the area, to move back 89 and 56 km (55 and 35 mi) from the border.[37]

On 11 October, Dejazmach Haile Selassie Gugsa and 1,200 of his followers surrendered to the commander of the Italian outpost at Adagamos. De Bono notified Rome and the Ministry of Information promptly exaggerated the importance of the surrender. Haile Selassie Gugsa was Emperor Haile Selassie's son-in-law. But less than a tenth of the Dejazmach's army defected with him.[39] On 14 October, De Bono issued a proclamation ordering the suppression of slavery. However, after a few weeks he was to write: "I am obliged to say that the proclamation did not have much effect on the owners of slaves and perhaps still less on the liberated slaves themselves. Many of the latter, the instant they are set free presented themselves to the Italian authorities, asking 'And now who gives me food'?"[39] The Ethiopians themselves had attempted to abolish slavery, but only in theory. Each Ethiopian Emperor since Tewodros II had issued "superficial" proclamations to halt slavery, but always without real effect. Only with the Italian proclamation of their Empire in summer 1936 was slavery totally and effectively abolished in Ethiopia.[40] By 15 October, De Bono's forces advanced from Adwa for a bloodless occupation of the holy capital of Axum. General de Bono entered the city riding triumphantly on a white horse. However, the invading Italians he commanded looted the Obelisk of Axum.

De Bono's advance continued methodically and, to Mussolini's consternation, a bit slowly. On 8 November, the I Corps and the Eritrean Corps captured Makale welcomed by the local population.[41] This proved to be the limit of how far the Italian invaders would get under the command of De Bono.[42] On 16 November, De Bono was promoted to the rank of Marshal of Italy (Maresciallo d'Italia), but by December he was replaced by Badoglio because of the slow, cautious nature of De Bono's advance.[43] In November the imprisoned former emperor Iyasu also died, in undetermined circumstances.

Ethiopian Christmas Offensive

the Christmas Offensive was intended to split the Italian forces in the north with the Ethiopian centre, crushing the Italian left with the Ethiopian right and to invade Eritrea with the Ethiopian left. Ras Seyum Mangasha held the area around Abiy Addi with about 30,000 men. Selassie with about 40,000 men advanced from Gojjam toward Mai Timket to the left of Ras Seyoum. Ras Kassa Haile Darge with around 40,000 men advanced from Dessie to support Ras Seyoum in the centre in a push towards Warieu Pass. Ras Mulugeta Yeggazu, the Minister of War, advanced from Dessie with approximately 80,000 men to take positions on and around Amba Aradam to the right of Ras Seyoum. Amba Aradam was a steep sided, flat topped mountain directly in the way of an Italian advance on Addis Ababa.[44] The four commanders had approximately 190,000 men facing the Italians. Ras Imru and his Army of Shire were on the Ethiopian left. Ras Seyoum and his Army of Tigre and Ras Kassa and his Army of Beghemder were the Ethiopian centre. Ras Mulugeta and his "Army of the Center" (Mahel Sefari) were on the Ethiopian right.[44]

A force of 1,000 Ethiopians crossed the Tekeze river and advanced toward the Dembeguina Pass (Inda Aba Guna or Indabaguna pass). The Italian commander, Major Criniti, commanded a force of 1,000 Eritrean infantry supported by L3 tanks. When the Ethiopians attacked, the Italian force fell back to the pass, only to discover that 2,000 Ethiopian soldiers were already there and Criniti's force was encircled. In the first Ethiopian attack, two Italian officers were killed and Criniti was wounded. The Italians tried to break out using their L3 tanks but the rough terrain immobilised the vehicles. The Ethiopians killed the infantry, then rushed the tanks and killed their two-man crews. Italian forces organised a relief column made up of tanks and infantry to relieve Critini but it was ambushed en route. Ethiopians on the high ground rolled boulders in front of and behind several of the tanks, to immobilise them, picked off the Eritrean infantry and swarmed the tanks. The other tanks were immobilised by the terrain, unable to advance further and two were set on fire. Critini managed to break-out in a bayonet charge and half escaped. The Ethiopians claimed to have killed 3,000 Eritrean troops during the Christmas offensive.

Black period

The ambitious Ethiopian plan called for Ras Kassa and Ras Seyoum to split the Italian army in two and isolate the Italian I Corps and III Corps in Mekele. Ras Mulugeta would then descend from Amba Aradam and crush both corps. According to this plan, after Ras Imru retook Adwa, he was to invade Eritrea. In November, the League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions. This excluded oil, however, an indispensable raw material for the conduct of any modern military campaign, and this favoured Italy.[45] The Ethiopian offensive was defeated by the Italian superiority in modern weapons like machine guns and heavy artillery. The Ethiopians were very poorly armed, with few machine guns, their troops mainly armed with swords and spears. After the killing of an Italian pilot Tito Minniti on 26 December, Badoglio received permission to use chemical warfare agents such as mustard gas. Mussolini stated that the gas used was not lethal but a mixture of tear gas and mustard gas (this gas was lethal in only about 1 percent of cases; its effectiveness was as a blistering agent).[46] His statement is contradicted however, by the large number of Ethiopian casualties from gas poisoning (over 100,000), and the many tons of mustard gas used by the Italians.

Second Italian advance

As the progress of the Christmas Offensive slowed, Italian plans to renew the advance on the northern front began Mussolini had given permission to use poison gas (but not mustard gas) and Badoglio received the Italian III Corps and the Italian IV Corps in Eritrea during early 1936. On 20 January, the Italians resumed their northern offensive at the First Battle of Tembien (20 to 24 January) in the broken terrain between the Warieu Pass and Makale. The forces of Ras Kassa were defeated, the Italians using poison gas (phosgene) and suffering 1,000 casualties against 8,000 Ethiopian casualties.

[It]...was at the time when the operations for the encircling of Makale were taking place that the Italian command, fearing a rout, followed the procedure which it is now my duty to denounce to the world. Special sprayers were installed on board aircraft so that they could vaporize, over vast areas of territory, a fine, death-dealing rain. Groups of nine, fifteen, eighteen aircraft followed one another so that the fog issuing from them formed a continuous sheet. It was thus that, as from the end of January 1936, soldiers, women, children, cattle, rivers, lakes, and pastures were drenched continually with this deadly rain. To systematically kill all living creatures, to more surely poison waters and pastures, the Italian command made its aircraft pass over and over again. That was its chief method of warfare.

— Selassie[47]

From 10 to 19 February, the Italians captured Amba Aradam and destroyed Ras Mulugeta's army in the Battle of Amba Aradam (Battle of Enderta). The Ethiopians suffered massive losses and poison gas destroyed a small part of Ras Mulugeta's army, according to the Ethiopians. During the slaughter following the attempted withdrawal of his army, both Ras Mulugeta and his son were killed. The Italians lost 800 killed and wounded while the Ethiopians lost 6,000 killed and 12,000 wounded. From 27 to 29 February, the armies of Ras Kassa and Ras Seyoum were destroyed at the Second Battle of Tembien. Ethiopians again argued that poison gas played a role in the destruction of the withdrawing armies. In early March, the army of Ras Imru was attacked, bombed and defeated in what was known as the Battle of Shire. The Italians suffered approximately 1,000 casualties and the Ethiopians 4,000, with almost the entire army neutralised as a fighting force.

On 31 March 1936 at the Battle of Maychew, the Italians defeated an Ethiopian counter-offensive by the main Ethiopian army commanded by Selassie. The outnumbered Ethiopians could not overcome the well-prepared Italian defences. For one day, the Ethiopians launched near non-stop attacks on the Italian and Eritrean defenders, until the exhausted Ethiopians withdrew while the Italians counter-attacked. The Regia Aeronautica attacked the survivors at Lake Ashangi with mustard gas. The Italians had 400 casualties, the Eritreans 873 and the Ethiopians 11,000. On 4 April, Selassie looked with despair upon the horrific sight of the dead bodies of his army ringing the poisoned lake.[48]

Southern front

On 3 October 1935, Graziani implemented the Milan Plan to remove Ethiopian forces from various frontier posts and to test the reaction to a series of probes all along the southern front. While incessant rains worked to hinder the plan, within three weeks the Somali villages of Kelafo, Dagnerai, Gerlogubi and Gorahai in Ogaden were in Italian hands.[49] Late in the year, Ras Desta Damtu assembled up his army in the area around Negele Borana, to advance on Dolo and invade Italian Somaliland. Between 12 and 16 January 1936, the Italians defeated the Ethiopians at the Battle of Genale Doria. The Regia Aeronautica destroyed the army of Ras Desta, Ethiopians claiming that poison gas was used.[50]

After a lull in February 1936, the Italians in the south prepared an advance towards the city of Harar. On 22 March, the Regia Aeronautica bombed Harar and Jijiga, reducing them to ruins even though Harar had been declared an "open city".[51] On 14 April, Graziani launched his attack against Ras Nasibu Emmanual to defeat the last Ethiopian army in the field at the Battle of the Ogaden. The Ethiopians were drawn up behind a defensive line that was termed the "Hindenburg Wall", designed by the chief of staff of Ras Nasibu, Wehib Pasha, a seasoned ex-Ottoman commander. After ten days, the last Ethiopian army had disintegrated; 2,000 Italian soldiers and 5,000 Ethiopian soldiers were killed or wounded.[52] On 2 May, Graziani requested permission from Mussolini to bomb Selassie when he found out that Haile Selassie had left Addis Ababa on the Imperial Railway. Mussolini refused his request, allowing Selassie to escape to Europe.[53]

March of the Iron Will

On 26 April 1936, Badoglio began "March of the Iron Will" from Dessie to Addis Ababa, an advance with a mechanised column against slight Ethiopian resistance.[54] On 2 May, Selassie boarded a train from Addis Ababa to Djibouti, with the gold of the Ethiopian Central Bank. From there he fled to England (he was allowed to do so by the Italians, who could have bombed and blocked or destroyed his train) and into exile. Before he departed, Selassie ordered that the government of Ethiopia be moved to Gore and ordered that the mayor of Addis Ababa maintain order in the city until the Italian arrival. and he appointed Haile Selassie as his Prince Regent during his absence. The city police, under Abebe Aregai and the remainder of the Imperial Guard did their utmost to restrain a growing crowd but rioters rampaged throughout the city, looting and setting fire to shops owned by Europeans.[55] Badoglio's force marched into Addis Ababa on 5 May and restored order.[56]

Aftermath

Analysis

King-Emperor Victor Emmanuel III waited for the crowds in the Quirinal Palace on Quirinal Hill. Months earlier, when the Ethiopian adventure first started, he told a friend: "If we win, I shall be King of Abyssinia. If we lose, I shall be King of Italy."[57] "Emperor! Emperor! Salute the Emperor!" ("Imperatore! Imperatore! Salute Imperatore!") chanted the crowd when Victor Emmanuel, in full Army uniform, showed himself on a balcony. The first Emperor in Rome in hundreds of years raised his withered hand to the visor of his cap and said nothing. Elena, his Queen-Empress, did not appear. She was in bed with a broken toe from falling off a stepladder in her library while reaching for a book.[58]

While the Italian King-Emperor was silent, Mussolini was not; when he announced victory from the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, the Italian population was jubilant.

From his balcony, Mussolini proclaimed

During the thirty centuries of our history, Italy has known many solemn and memorable moments – this is unquestionably one of the most solemn, the most memorable. People of Italy, people of the world, peace has been restored.[59]

The crowds would not let him go—ten times they recalled Mussolini to the balcony and cheered and waved while the boys of various Fascist youth organisations sang the newly composed 'Hymn of the Empire' (Inno dell'impero)."[59]

Four days later, the same scene was repeated when Il Duce in a speech about the "shining sword" and the "fatal hills of Rome" announced

At last Italy has her empire." And he then added: "The Italian people have created an empire with their blood. They will fertilize it with their work. They will defend it against anyone with their weapons. Will you be worthy of it?"

— Barker[59]

Fascism was never so popular and the shouts of military victory drowned out the muttered grumbles about some underlying economic ills.[60]

While the Italian people were rejoicing in Rome, Haile Selassie sailed from Djibouti on 4 May, he had sailed from Djibouti in the British cruiser HMS Enterprise. From Mandatory Palestine Selassie sailed to Gibraltar en route for Britain. In Jerusalem, Haile Selassie sent a telegram to the League of Nations,

We have decided to bring to an end the most unequal, most unjust, most barbarous war of our age, and have chosen the road to exile in order that our people will not be exterminated and in order to consecrate ourselves wholly and in peace to the preservation of our empire's independence... we now demand that the League of Nations should continue its efforts to secure respect for the covenant, and that it should decide not to recognize territorial extensions, or the exercise of an assumed sovereignty, resulting from the illegal recourse to armed force and to numerous other violations of international agreements.[61]

The Ethiopian Emperor's telegram caused several nations temporarily to defer recognition of the Italian conquest.[61]

On 30 June, Selassie spoke at the League of Nations and was introduced by the President of the Assembly as "His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Ethiopia" ("Sa Majesté Imperiale, l'Empereur d'Ethiopie"). A group of jeering Italian journalists began yelling insults and had to be ejected before he could speak. The Romanian chairman, Nicolae Titulescu, jumped to his feet and shouted "Show the savages the door!" ("A la porte les sauvages!").[62] Selassie denounced Italian aggression and criticised the world community for standing by. At the conclusion of his speech, which appeared on newsreels throughout the world, he said "It is us today. It will be you tomorrow". France appeased Italy because it could not afford to risk an alliance between Italy and Germany; Britain decided its military weakness meant it had to follow France's lead.[63][64] Selassie's resolution to the League to deny recognition of the Italian conquest was defeated and he was denied a loan to finance a resistance movement.[59] On 4 July 1936, the League voted to end the sanctions imposed against Italy in November 1935 and by 15 July, the sanctions were at an end.[65][d]

On 18 November 1936, the Italian Empire was recognised by the Empire of Japan and Italy recognised the Japanese occupation of Manchuria; The Stresa Front was over.[67][68] Hitler had supplied the Ethiopians with 16,000 rifles and 600 machine guns in the hope that Italy would be weakened when he moved against Austria.[69] By contrast, France and Britain recognised Italian control over Ethiopia in 1938. Mexico was the only country to strongly condemn Italy's sovereignty over Ethiopia, respecting Ethiopian independence throughout. Mexico was amongst only six nations in 1937 which did not recognise the Italian occupation, along with China, New Zealand, the Soviet Union, the Republic of Spain and the United States.[70][71] Three years later, only the USSR officially recognised Selassie and the United States government considered recognising the Italian Empire with Ethiopia included.[72] The invasion of Ethiopia and its general condemnation by Western democracies isolated Mussolini and Fascist Italy. From 1936 to 1939, Mussolini and Hitler joined forces in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. In April 1939, Mussolini launched the Italian invasion of Albania. In May, Italy and Nazi Germany joined together in the Pact of Steel. In September 1940, both nations signed the Tripartite Pact along with the Empire of Japan.

War crimes

Ethiopian troops used Dum-Dum bullets, which had been banned by declaration IV, 3 of the Hague Convention, 1899 and began mutilating captured Eritrean Askari (often with castration) in the first weeks of war.[73] After December, the Ethiopians began to torture Italians, who retaliated with the use of poison gas. Italian military forces disposed of a vast arsenal of grenades and bombs loaded with mustard gas which had been transported by ship through the Suez canal before the war.[citation needed] The Italian army used 300–500 t (300–490 long tons) of mustard gas, despite being a signatory to the 1925 Geneva Protocol, justified by the deaths of Minniti and his observer in the Ogaden.[74] The use of gas was authorised by Mussolini,

Rome, October 27, 1935. To His Excellency Graziani. The use of gas as an ultima ratio to overwhelm enemy resistance and in case of counterattack is authorized. Mussolini.

Rome, December 28, 1935. To His Excellency Badoglio. Given the enemy system I have authorized Your Excellency the use even on a vast scale of any gas and flamethrowers. Mussolini.[citation needed]

Military and civilian targets and Red Cross camps and ambulances were gassed.[75] Count Carl Gustaf von Rosen served as an ambulance pilot and he later recounted that a hospital was bombed with mustard gas, despite being marked with Red Crosses. The Swedish Red Cross secured photographic evidence of Ethiopian civilians with mustard gas injuries.[76] Mustard gas was also sprayed from above on Ethiopian combatants and villages. The Italians tried to keep their resort to chemical warfare secret but were exposed by the International Red Cross and many foreign observers. The Italians claimed that at least 19 bombardments of Red Cross tents "posted in the areas of military encampment of the Ethiopian resistance", had been "erroneous".

The Italians attempted to justify their use of chemical weapons by citing the exception to the Geneva Protocol restrictions that referenced acceptable use for reprisal against illegal acts of war. They stated that the Ethiopians had tortured or killed their prisoners and wounded soldiers.

— Smart[77]

The Italians delivered poison gas by artillery canisters and in bombs dropped by the Regia Aeronautica. Though poorly equipped, the Ethiopians had achieved some success against modern weaponry but had no defence against the "terrible rain that burned and killed".[78] Anthony Mockler wrote that the effect mustard gas in battle was negligible and in 1959, D. K. Clark wrote that the US Major Norman Fiske

....thought the Italians were clearly superior and that victory for them was assured no matter what. The use of chemical agents in the war was nothing more than an experiment. He concluded "From my own observations and from talking with [Italian] junior officers and soldiers I have concluded that gas was not used extensively in the African campaign and that its use had little if any effect on the outcome".

— D. K. Clark[79]

Italians, like the war correspondent Indro Montanelli, noted that the Italian soldiers had no gas masks, that there was no use of gas or it was used in very small amounts if at all.[80]

Other personalities of the war

- Giacomo Appiotti – Commanded 3rd "21st April" Blackshirt Division

- Menen Asfaw – Empress of Ethiopia

- Sidney Barton - British Minister to Ethiopia

- Ettore Bastico – Commanded the 1st "23rd March" Blackshirt Division and III Corps

- Galeazzo Ciano – Mussolini's son-in-law, commanded a bomber squadron nicknamed "The Reckless" (La Disperata)

- Makonnen Endelkachew – Commander of the Army of Illubabor

- Roberto Farinacci – Served as a member of the Voluntary Militia for National Security (Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, or MVSN) and eventually attained the rank of Lieutenant General, he lost a hand while fishing with a grenade

- Italo Gariboldi – Commander of the 30th "Sabauda" Infantry Division

- Oliver Law – Supporter of Ethiopia

- Tekle Hawariat Tekle Mariyam – Ethiopia's Representative at the League of Nations

- Vittorio Mussolini – Mussolini's son, he and his younger brother Bruno crewed Italian bombers

- Sylvia Pankhurst – Supporter of Ethiopia

- Alessandro Pavolini – President of the Fascist Confederation of Professionals and Artists, served as a Lieutenant

- Balcha Safo – An aged Ethiopian fighter and former Governor of the Sidamo Province

- Achille Starace – Party Secretary of the National Fascist Party, commanded the East African Fast Column (Colonna Celere de Africa Orientale) – See Battle of Shire

- Asfaw Wossen Taffari – Crown Prince of Ethiopia and the commander of the Wollo provincial forces

- Wolde Giyorgis Wolde Yohannes – Haile Selassie's private secretary

- Lydia Gowrie Kimber – founder of the British Abyssinian Refugee Relief Committee, organised fund raising and political support for Haile Selassie during his stay in England. He presented a leopard skin to her on his 1967 visit to open the Ethiopian Pavilion at the Expo 67 world's fair in Montreal, Canada.[81]

- Haile Selassie Gugsa – Dejazmatch who defected and collaborated with the Fascist military of Italy.[43][82][page needed][83]

Italian occupation

1936

On 10 May 1936, in Ethiopia Italian troops from the northern front and from the southern front met at Dire Dawa.[84] The Italians found the recently released Ethiopian Ras, Hailu Tekle Haymanot, who boarded a train back to Addis Ababa and approached the Italian invaders in submission.[85] Selassie fell back to Gore in southern Ethiopia to reorganise and continue to resist the Italians. In early June, Rome promulgated a constitution for Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI, Italian East Africa) bringing Ethiopia, Eritrea and Italian Somaliland together into an administrative unit of six provinces. Badoglio became the first Viceroy and Governor General but on 11 June, he was replaced by Marshal Graziani. In July, Ethiopian forces attacked Addis Ababa and were routed. Numerous members of Ethiopian royalty were taken prisoner and others were executed soon after they surrendered, including three sons of Ras Kassa. On 19 December, Wondosson Kassa was executed near Debre Zebit and on 21 December, Aberra Kassa and Asfawossen Kassa were executed in Fikke. In late 1936, after the Italians tracked him down in Gurage, Dejazmach Balcha Safo was killed resisting to the end.[86] On 19 December, Selassie surrendered at the Gojeb river.[87]

The capture of Ras Imru ended the resistance movement known as the "Black Lions". Imru was flown to Italy and imprisoned on the Island of Ponza, while the rest of the Ethiopian prisoners were dispersed in camps in East Africa and Italy.

Mussolini ordered that

Rome, June 5, 1936. To His Excellency Graziani. All rebels taken prisoner must be killed. Mussolini.[88][page needed]

Rome, July 8, 1936. To His Excellency Graziani. I have authorized once again Your Excellency to begin and systematically conduct a politics of terror and extermination of the rebels and the complicit population. Without the lex talionis one cannot cure the infection in time. Await confirmation. Mussolini.[88][page needed]

Most of the repression of the population was carried out by colonial troops (mostly from Eritrea) of the Italians who, according to the Ethiopians, instituted forced labour camps, installed public gallows, killed hostages and mutilated the corpses of their enemies. Many Italian troops had themselves photographed next to cadavers hanging from the gallows or standing with chests full of detached heads.[89][90]

Catholic reaction was mixed to the Italian conquest of Ethiopia. Fearing retribution from the National Fascist Party, some bishops gave praise. In 1973, Anthony Rhodes wrote,

In his Pastoral Letter of the 19th October [1935], the Bishop of Udine [Italy] wrote, ‘It is neither timely nor fitting for us to pronounce on the rights and wrongs of the case. Our duty as Italians, and still more as Christians is to contribute to the success of our arms.’ The Bishop of Padua wrote on the 21st October, ‘In the difficult hours through which we are passing, we ask you to have faith in our statesmen and armed forces.’ On the 24th October, the Bishop of Cremona consecrated a number of regimental flags and said: ‘The blessing of God be upon these soldiers who, on African soil, will conquer new and fertile lands for the Italian genius, thereby bringing to them Roman and Christian culture. May Italy stand once again as the Christian mentor to the whole world.

— [91][page needed]

Pope Pius XI (who had previously condemned totalitarianism in the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno) continued his implicit criticism of the Italian regime.[e] This coincided with Mussolini's increasing anti-clericalism, of which he stated that "the Papacy was a malignant tumor in the body of Italy and must 'be rooted out once and for all', because there was no room in Rome for both the Pope and [himself]".[92]

In December, Graziani declared the country to be pacified and under Italian control. Ethiopian resistance continued and the Italian occupation was marked by guerilla campaigns against the Italians and Italian reprisals, including mustard gas attacks against rebels and the summary execution of prisoners. After the beginning of 1937, the number of Ethiopians enrolling in the Italian colonial forces was grew. On 19 February 1937, during a public ceremony at the Viceregal Palace in Addis Ababa (the former Imperial residence), Abraha Deboch and Moges Asgedom attempted to kill Graziani with hand grenades and the Italian security guard fired indiscriminately into the crowd of civilian onlookers. Over the following weeks the colonial authorities executed about 30,000 persons in retaliation, including about half of the younger, educated Ethiopian population, which became known as Yekatit 12 (the Ethiopian calendar equivalent of 19 February).[93][page needed] In December, Ras Desta Damtew had been flushed from his base of operations in Irgalem and was executed on 24 February; Dejazmach Beyene Merid who had just joined forces with him was also killed.

1938–1940

On 21 December 1937, Rome appointed Amedeo, 3rd Duke of Aosta, as the new Viceroy and Governor General of AOI with instructions to take a more conciliatory line. Aosta instituted public works projects including 3,200 km (2,000 mi) of new paved roadways, 25 hospitals, 14 hotels, dozens of post offices, telephone exchanges, aqueducts, schools and shops. The Italians decreed miscegenation to be illegal. Racial separation, including residential segregation, was enforced as thoroughly as possible and the Italians showed favouritism to non-Christian groups. To isolate the dominant Amhara rulers of Ethiopia, who supported Selassie, the Italians granted the Oromos, the Somalis and other Muslims, many of whom had supported the invasion, autonomy and rights. The Italians also definitively abolished slavery and abrogated feudal laws that had been upheld by the Amharas. Early in 1938, a revolt broke out in Gojjam, led by the Committee of Unity and Collaboration, made up of some of the young, educated elite who had escaped reprisals after the assassination attempt on Graziani.

Britain and France recognised Italian sovereignty over Ethiopia by the Anglo-Italian Agreements of 1938. The army of occupation had 150,000 men but was spread thinly; by 1941 the garrison had been increased to 250,000 soldiers, including 75,000 Italian civilians. The former police chief of Addis Ababa, Abebe Aregai, was the most successful leader of the Ethiopian guerrilla movement after 1937, using units of fifty men. On 11 December, the League of Nations voted to condemn Italy and Mussolini withdrew from the League. Along with world condemnation, the occupation was expensive, the budget for AOI from 1936 to 1937 required 19.136 billion lire for infrastructure, when the annual revenue of Italy was only 18.581 billion lire.[94] In 1939 Ras Sejum Mangascià, Ras Ghetacciù Abaté and Ras Kebbedé Guebret submitted to the Italian Empire and guerilla warfare petered out. In early 1940, the last area of guerilla activity was around lake Tana and the southern Gojjam, under the leadership of the degiac Mangascià Giamberè and Belay Zelleke.[95]

East African campaign, 1940–1941

While in exile in England, Haile Selassie had sought to gain the support of the Western democracies for his cause but he had little success until the Second World War began. On 10 June 1940, Mussolini declared war on France and Britain and attacked British and Commonwealth forces in the Sudan, Kenya and British Somaliland. In August, the Italian conquest of British Somaliland was completed. The British and Selassie sought to co-operate with Ethiopian and other local forces in a campaign to dislodge the Italians from Ethiopia. Selassie went to Khartoum to establish closer liaison with the British and resistance forces within Ethiopia. On 18 January 1941, Selassie crossed the border into Ethiopia near the village of Um Iddla and two days later rendezvoused with Gideon Force and on 5 May, Selassie and an army of Ethiopian Free Forces entered Addis Ababa.[96] After the Italian defeat, an Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia was carried out by remnants of Italian troops and their allies, which lasted until the Armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces in September 1943.

Peace treaty, 1947

The treaty signed in Paris by the Italian Republic (Repubblica Italiana) and the victorious powers of World War II on 10 February, included formal Italian recognition of Ethiopian independence and an agreement to pay $25,000,000 in reparations. Ethiopia became independent again and Selassie was restored as its leader. Ethiopia presented bill to the Economic Commission for Italy of £184,746,023 for damages inflicted during the course of the Italian occupation. Claimed were the loss of 2,000 churches, 525,000 houses and the slaughter and/or confiscation of six million beef cattle, seven million sheep and goats, one million horses and mules and 700,000 camels.[59] The Ethiopians recorded 275,000 combatants killed in action, 78,500 patriots killed during the occupation (1936–1941), 17,800 civilians killed by bombing and 30,000 in the February 1937 massacre, 35,000 people died in concentration camps, 24,000 patriots executed by Summary Courts, 300,000 persons died of privation due to the destruction of their villages, amounting to 760,300 human deaths.[59] The Italians disputed this huge amount, arguing that real Ethiopian casualties were half the Ethiopian claim.[97]

Protest by Tagore in 1937

Famous Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore who was awarded Nobel Prize in literature protested this invasion. He wrote a poem named Africa in Bengali on 10th February 1937. Later it was translated in English by William Radice. He criticized the colonization of Africa. He was against imperialism. He was deeply sorrowed for the destruction of African culture by the Western people. In his poem he prayed for peace in Africa.

See also

- First Italo-Ethiopian War

- Timeline of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

- Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

- Censorship in Italy

Notes

- ^ Angelo Del Boca cited a 1945 memorandum from Ethiopia to the Conference of Prime Ministers, which tallies 760,300 natives dead; of them, battle deaths: 275,000, hunger among refugees: 300,000, patriots killed during occupation: 78,500, concentration camps: 35,000, Feb. 1937 massacre: 30,000, executions: 24,000, civilians killed by air force: 17,800.[7]Secondary Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century

- ^ According to Time Magazine, 110 Ethiopians were killed and 30 Italians were killed.[11] According to Mockler, 107 Ethiopians were killed and 40 wounded and 50 Italians and Somalis were killed.[12]

- ^ Examples of ferenghi, Evelyn Waugh, Daily Mail a reporter and author of the novel Scoop; Bill Deedes, journalist and possible inspiration for William Boot in Scoop, George Steer, journalist for The Times, Linton Wells and Fay Gillis Wells, reporters, Karl von Wiegand, journalist, Webb Miller war correspondent, Andrew Fountaine an ambulance driver, Hubert Julian, pilot, Marcel Junod, Red Cross doctor, Count Carl Gustaf von Rosen, Swedish Red Cross pilot – Red Cross facilities were bombed regularly by the Italians.[29], Wehib Pasha, military advisor, John H. Spencer, advisor, Adolf Parlesák, military advisor, John Robinson, aviator, Eric Virgin, advisor to Haile Selassie.[30] Viking Tamm, military advisor, established a Swedish military academy in Holeta Genet[30] Thomas Lambie an American missionary doctor who became an Ethiopian citizen and stayed in the country.

- ^ In 1976, Baer wrote that Selassie's resolution requesting loans was defeated by a vote of 23 against, 25 abstentions and 1 vote for (from Ethiopia). In the sanctions vote, 44 delegates approved the ending of sanctions, 4 abstained and 1 (Ethiopian) delegate voted for retention.[66]

- ^ Biographies, Pope Pius XI. "The closing years of Pius XI's reign were marked by a close association with the Western democracies, as these nations and the Vatican found that they were both threatened by the totalitarian regimes and ideologies of Hitler, Mussolini, and the Soviet Union."

References

- ^ a b c Stapleton 2013, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Barker 1971, p. 20.

- ^ a b Sbacchi 1978, p. 37.

- ^ Sbacchi 1978, p. 36.

- ^ a b Sbacchi 1978, p. 43.

- ^ Sbacchi 1978, p. 38.

- ^ Del Boca 1965.

- ^ Sullivan 1999, pp. 188.

- ^ Baer 1976, p. 279.

- ^ Burgwyn 1997, p. 138.

- ^ Time Magazine, Provocations.

- ^ Mockler 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Shinn & Ofcansky 2013, p. 392.

- ^ Stearns & Langer 2002, p. 677.

- ^ Crozier 2004, p. 108.

- ^ Stackelberg 2009, p. 164.

- ^ Clarke 1999, pp. 9–20.

- ^ Mockler 2003, p. 75.

- ^ "Selassie's Guard Fights on UN Side". Eugene Register-Guard. 2 June 1951.

- ^ "Haile Selassie's Draft Order". The Afro American. 17 April 1948.

- ^ Pankhurst 1968, pp. 605–608.

- ^ a b c Barker 1971, p. 29.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 57.

- ^ Shinn & Ofcansky 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Othen 2017, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Othen 2017, p. 238.

- ^ Nicolle 1997, p. 18.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 47.

- ^ Time Magazine, Ethiopia's Lusitania?

- ^ a b Spencer 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Baer 1976, p. 13.

- ^ Crociani & Viotti 1980.

- ^ Nicolle 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Reparti volontari argentini (in Italian)

- ^ Gooch 2007, p. 301.

- ^ Gooch 2007, p. 299.

- ^ a b c Barker 1971, p. 33.

- ^ Nicolle 1997, p. 11.

- ^ a b Barker 1971, p. 35.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 1989, p. 103.

- ^ "Archivio Storico Istituto Luce - video". Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 36.

- ^ a b Nicolle 1997, p. 8.

- ^ a b Barker 1971, p. 45.

- ^ Palla 2000, p. 104.

- ^ Mussolini and the gas (in Italian).

- ^ Safire 1997, p. 318.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 105.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 70.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 76.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 112.

- ^ Barker 1971, pp. 123, 121.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 126.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 109.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 125.

- ^ "Archivio Storico Istituto Luce - video". Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Time magazine, "Re ed Imperatore", 18 May 1936

- ^ Time, "Re ed Imperatore", 18 May 1936

- ^ a b c d e f Barker 1971, p. 159.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 131.

- ^ a b Barker 1971, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 133.

- ^ Salerno 1997, pp. 66–104.

- ^ Old 2011, pp. 1, 381–1, 401.

- ^ Baer 1976, p. 299.

- ^ Baer 1976, p. 298.

- ^ Lowe & Marzari 2010, p. 307.

- ^ Selassie 1999, p. 20.

- ^ Leckie 1987, p. 64.

- ^ USSD 1943, pp. 28–32.

- ^ Selassie 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Lamb 1999, p. 214.

- ^ Antonicelli 1975, p. 79.

- ^ Baudendistel 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Bernard Bridel, Les ambulances à Croix-Rouge du CICR sous les gaz en Ethiopie, Le Temps, 13 August 2003, in French, hosted at the International Committee of the Red Cross website

- ^ (in Swedish).

- ^ Smart 1997, pp. 1–78.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 56.

- ^ Clark 1959, p. 20.

- ^ "Dai parolai mi guardi Iddio che dagli intenditori mi guardo io di Filippo Giannini - Repubblica Dominicana - Il Corriere d'Italia nel Nuovo Mondo". Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Montreal Star

- ^ Mockler 2003.

- ^ Shinn & Ofcansky 2013, p. 117.

- ^ Nicolle 1997, p. 12.

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 127.

- ^ Selassie 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Mockler 2003, p. 168.

- ^ a b Candeloro 1981.

- ^ Del Boca 2005.

- ^ Mignemi 1982.

- ^ Rhodes 1973.

- ^ Mack Smith 1982, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Del Boca & Rochat 1996.

- ^ Cannistraro 1982, p. 5.

- ^ Missione Barontini in Ethiopia (in Italian)

- ^ Barker 1971, p. 156.

- ^ "WAR STATS REDIRECT". Retrieved 24 May 2015.

Sources

Books

- Antonicelli, Franco (1975). Trent'anni di storia italiana: dall'antifascismo alla Resistenza (1915–1945) lezioni con testimonianze. Reprints Einaudi (in Italian). Torino: Giulio Einaudi Editore. OCLC 878595757.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Baer, George W. (1976). Test Case: Italy, Ethiopia, and the League of Nations. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institute Press, Stanford University. ISBN 978-0-8179-6591-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Barker, A. J. (1971). Rape of Ethiopia, 1936. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-02462-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Baudendistel, Reiner (2006). Between Bombs and Good Intentions: The Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Human Rights in Context. Vol. I. Oxford: Berghahn. ISBN 978-1-84545-035-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Burgwyn, H. J. (1997). Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918–1940. Praeger Studies of Foreign Policies of the Great Powers. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-94877-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Candeloro, Giorgio (1981). Storia dell'Italia Moderna (in Italian) (10th ed.). Milano: Feltrinelli. OCLC 797807582.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Cannistraro, Philip V. (1982). Historical Dictionary of Fascist Italy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-21317-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Clarence-Smith, W. G. (1989). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-3359-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Clark, D. K. (1959). Effectiveness of Toxic Chemicals in the Italo–Ethiopian War. no isbn. Bethesda, MD: Operations Research Office.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Crociani, P.; Viotti, A. (1980). Le Uniformi Dell' A.O.I., Somalia, 1889–1941 (in Italian). Roma: La Roccia. OCLC 164959633.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Crozier, Andrew J. (2004). The Causes of the Second World War. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18601-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Del Boca, A. (1965). La guerra d'Abissinia: 1935–1941 (in Italian). Milano: Feltrinelli. OCLC 799937693.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Del Boca, Angelo; Rochat, Giorgio (1996). I gas di Mussolini: il fascismo e la guerra d'Etiopia. Primo piano (in Italian). Roma: Editori Riuniti. ISBN 978-88-359-4091-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - del Boca, Angelo (2005). Italiani, brava gente? Un mito duro a morire. I colibrì (in Italian). Vicenza: N. Pozza. ISBN 978-88-545-0013-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Gooch, John (2007). Mussolini and His Generals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 660. ISBN 978-0-521-85602-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lamb, Richard (1999). Mussolini as Diplomat. New York: Fromm International. ISBN 978-0-88064-244-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Leckie, Robert (1987). Delivered from Evil: The Saga of World War II. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-015812-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lowe, Cedric James; Marzari, F. (2010) [1975]. Italian Foreign Policy 1870–1940. Foreign Policies of the Great Powers. Vol. VIII (online ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-88880-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mack Smith, D. (1982). Mussolini: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-50694-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mignemi, A., ed. (1982). Si e no padroni del mondo. Etiopia 1935–36. Immagine e consenso per un impero (in Italian). Novara: Istituto Storico della Resistenza in Provincia Novara Piero Fornara. OCLC 878601977.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mockler, Anthony (2003). Haile Selassie's War. New York: Olive Branch Press. ISBN 978-1-56656-473-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nicolle, David (1997). The Italian Invasion of Abyssinia 1935–1936. Westminster, MD: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-692-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Othen, Christopher. Lost Lions of Judah: Haile Selassie's Mongrel Foreign Legion. 2017: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-5983-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Palla, Marco (2000). Mussolini and Fascism. Interlink Illustrated Histories. New York: Interlink Books. ISBN 978-1-56656-340-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Pankhurst, R. (1968). A Brief Note on the Economic History of Ethiopia from 1800 to 1935. Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University. OCLC 434191.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Peace and War: United States Foreign Policy 1931–1941 (online ed.). Washington, DC: State Department. 1983 [1943]. OCLC 506009610. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Rhodes, A. (1973). The Vatican in the Age of the Dictators: 1922–1945. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-02394-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Safire, William (1997). Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History (rev. expanded ed.). New York: norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04005-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Haile Selassie I: My Life and Ethiopia's Progress: The Autobiography of Emperor Haile Selassie I, King of Kings and Lord of Lords. Vol. II. Edited by Harold Marcus with others and Translated by Ezekiel Gebions with others. Chicago: Research Associates School Times Publications. 1999. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-948390-40-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Shinn, D. H.; Ofcansky, T. P. (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Historical dictionaries of Africa (2nd ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7194-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Smart, J. K. (1997). "History of Chemical and Biological Warfare: An American Perspective". In Zajtchuk, Russ (ed.). Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare (PDF). Textbook of Military Medicine: Warfare, Weaponry and the Casualty. Vol. III. Part I (online ed.). Bethesda, MD: Office of The Surgeon General Department of the Army, United States of America. OCLC 40153101. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Spencer, John H. (2006). Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years. Hollywood, CA: Tsehai. ISBN 978-1-59907-000-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Stackelberg, R. (2009). Hitler's Germany: Origins, Interpretations, Legacies (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-37331-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Stapelton, Timothy J. (2013). A Military History of Africa: The Colonial Period: from the Scramble for Africa to the Algerian Independence War (ca. 1870–1963). Vol. II. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39570-3.

- Sullivan, Barry (1999). "More than Meets the Eye: The Ethiopian War and the Origins of the Second World War". In Martel, G. (ed.). The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered A. J. P. Taylor and the Historians (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 178–203. ISBN 978-0-415-16325-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Encyclopaedias

- Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2002). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern (6th, online ed.). New York: Bartleby.com. OCLC 51671800.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Journals

- Calvitt Clark, J. (1999). "Japan and Italy squabble over Ethiopia: The Sugimura affair of July 1935". Selected Annual Proceedings of the Florida Conference of Historians: 9–20. ISSN 2373-9517. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 8 June 2010 suggested (help) - Old, Andrew (2011). "'No more Hoares to Paris': British Foreign Policymaking and the Abyssinian Crisis, 1935". Review of International Studies. 37 (3): 1383–1401. ISSN 0260-2105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sbacchi, Alberto (1978). Marcus, H. G. (ed.). "The Price of Empire: Towards an Enumeration of Italian Casualties in Ethiopia 1935–40". Ethiopianist Notes. II (2). ISSN 1063-2751.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Salerno, Reynolds M. (1997). "The French Navy and the Appeasement of Italy, 1937–9". The English Historical Review. CXII (445). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 66–104. ISSN 0013-8266.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- De Bono, E. (1937). La conquista dell' Impero La preparazione e le prime operazioni. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Roma: Istituto Nazionale Fascista di Cultura. OCLC 46203391.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Giannini, Filippo; Mussolini, Guido (1999). Benito Mussolini, l'uomo della pace: da Versailles al 10 giugno 1940. Roma: Editoriale Greco e Greco. ISBN 978-88-7980-133-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Graziani, R. (1938). Il fronte Sud (in Italian). Milano: A. Mondadori. OCLC 602590204.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Kershaw, Ian (1999). Hitler: 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04671-7.

- Matthews, Herbert Lionel (1937). Eyewitness in Abyssinia: With Marshal Bodoglio's forces to Addis Ababa. London: M. Secker & Warburg. OCLC 5315947.

- Shinn, David Hamilton; Prouty, Chris; Ofcansky, Thomas P. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4910-5.

- Starace, A. (1937). La marcia su Gondar della colonna celere A.O. e le successive operazioni nella Etiopia Occidentale. Milano: A. Mondadori. OCLC 799891187.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Walker, Ian W. (2003). Iron Hulls, Iron Hearts: Mussolini's elite Armoured Divisions in North Africa. Marlborough: Crowood. ISBN 978-1-86126-646-0.

Videography

- Template:En icon Fascist Legacy, Ken Kirby, Royaume-Uni, 1989, documentary 2x50min Fascist Legacy on YouTube

- Template:En icon Italo-Ethiopian war on YouTube

- Template:It icon Italian videos of the Italian conquest of Ethiopia on YouTube

Audio

External links

- Speech to the League of Nations, June 1936 (full text)

- British newsreel footage of Haile Selassie's address to the League of Nations

- Regio Esercito: La Campagna d'Etiopia

- Ethiopia 1935–36: mustard gas and attacks on the Red Cross (Full version in French) – Bernard Bridel, Le Temps

- The use of chemical weapons in the 1935–36 Italo-Ethiopian War – SIPRI Arms Control and Non-proliferation Programme, October 2009

- Mussolini's Invasion and the Italian Occupation

- Mussolini's Ethiopia Campaign

- OnWar: Second Italo–Abyssinian War 1935–1936

- Haile Selassie I, Part 2

- OneWorld Magazine: Hailé Selassié VS. Mussolini

- The Day the Angel Cried

- The Emperor Leaves Ethiopia

- Ascari: I Leoni di Eritrea/Ascari: The Lions of Eritrea. Second Italo-Abyssinian war. Eritrea colonial history, Eritrean ascari pictures/photos galleries and videos, historical atlas...

- Ross, F. 1937. The Strategical Conduct of the Campaign and supply and Evacuation Programmes

- Time, Monday, 11 May 1936, "Empire's End"

- Time, Monday, 18 May 1936, "Occupation"

- Time, Monday, 18 May 1936, "Re ed Imperatore"

- Use dmy dates from August 2013

- Second Italo-Ethiopian War

- Italian East Africa

- 1935 in Ethiopia

- 1936 in Ethiopia

- 1935 in Italy

- 1936 in Italy

- Conflicts in 1935

- Conflicts in 1936

- History of Ethiopia

- Interwar period

- Invasions

- Italy in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

- Wars involving Ethiopia

- Wars involving Italy

- Haile Selassie

- Ethiopia–Italy military relations