Jewish art: Difference between revisions

→Israel: Added a bit of info and further info template to related articles. |

→Eastern Europe: Christian art link |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

Early critics like [[Meir Balaban|Majer Bałaban]] viewed Jewish art broadly, including any object that exhibited “features of Jewish creativity,” while [[Abram Efros]] contended that Jewish artists should be recognized within the national contexts of their residence, arguing, “Jewish artists belong to the art of the country where they live and work”. Following the emancipation, figures such as [[Maurycy Gottlieb]] blurred traditional boundaries, integrating Jewish themes into a broader Christian iconographic tradition, laying foundational elements for Jewish genre painting. The late 19th and early 20th centuries with the rise of Jewish nationalism added an ideological dimension to Jewish art, with Jewish genre painting used by some as medium for expressing Zionist revival and the Jewish experience of exile.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |title=YIVO {{!}} Painting and Sculpture |url=https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/painting_and_sculpture |access-date=2024-03-28 |website=yivoencyclopedia.org}}</ref> Religious art and architecture manifested also in wooden synagogues in Eastern Europe which would eventually be destroyed by the Nazis in the Second World war.<ref>{{Citation |last=Hubka |first=Thomas C. |title=Jewish Art and Architecture in the East European Context: The Gwoździec-Chodorów Group of Wooden Synagogues |date=1997 |work=Jews in Early Modern Poland |pages=141–182 |editor-last=Hundert |editor-first=Gershon David |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/jews-in-early-modern-poland/jewish-art-and-architecture-in-the-east-european-context-the-gwozdziecchodorow-group-of-wooden-synagogues/11DD0983F6B0366F59CD9AC1D519DB7B |access-date=2024-03-28 |series=Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry |publisher=Liverpool University Press |isbn=978-1-874774-31-0}}</ref> |

Early critics like [[Meir Balaban|Majer Bałaban]] viewed Jewish art broadly, including any object that exhibited “features of Jewish creativity,” while [[Abram Efros]] contended that Jewish artists should be recognized within the national contexts of their residence, arguing, “Jewish artists belong to the art of the country where they live and work”. Following the emancipation, figures such as [[Maurycy Gottlieb]] blurred traditional boundaries, integrating Jewish themes into a broader Christian iconographic tradition, laying foundational elements for Jewish genre painting. The late 19th and early 20th centuries with the rise of Jewish nationalism added an ideological dimension to Jewish art, with Jewish genre painting used by some as medium for expressing Zionist revival and the Jewish experience of exile.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |title=YIVO {{!}} Painting and Sculpture |url=https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/painting_and_sculpture |access-date=2024-03-28 |website=yivoencyclopedia.org}}</ref> Religious art and architecture manifested also in wooden synagogues in Eastern Europe which would eventually be destroyed by the Nazis in the Second World war.<ref>{{Citation |last=Hubka |first=Thomas C. |title=Jewish Art and Architecture in the East European Context: The Gwoździec-Chodorów Group of Wooden Synagogues |date=1997 |work=Jews in Early Modern Poland |pages=141–182 |editor-last=Hundert |editor-first=Gershon David |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/jews-in-early-modern-poland/jewish-art-and-architecture-in-the-east-european-context-the-gwozdziecchodorow-group-of-wooden-synagogues/11DD0983F6B0366F59CD9AC1D519DB7B |access-date=2024-03-28 |series=Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry |publisher=Liverpool University Press |isbn=978-1-874774-31-0}}</ref> |

||

The works of artists such as [[Szmul Hirszenberg]] and [[Isidor Kaufmann|Izidor Kaufmann]] showcased an interweaving of Jewish narratives with a universal moral vocabulary, drawing mainly on Christian allegories to depict Jewish suffering and resilience. Their art, while deeply rooted in Jewish experiences, mirrored the allegorical and dramatic modes prevalent in Christian painting, responding to the artistic and ideologies of the time. An example being Hirszenberg’s works, such as "Golus" and "Czarny Sztandar" (The Black Banner, 1907, Jewish Museum, New York), used Christian allegories to communicate broader themes of exile, suffering, and redemption, embodying the tension between death and resurrection characteristic of Christian imagery.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Jewish Museum |url=https://thejewishmuseum.org/index.php/collection/19689-the-black-banner |access-date=2024-03-28 |website=The Jewish Museum}}</ref><ref name=":5" /> |

The works of artists such as [[Szmul Hirszenberg]] and [[Isidor Kaufmann|Izidor Kaufmann]] showcased an interweaving of Jewish narratives with a universal moral vocabulary, drawing mainly on Christian allegories to depict Jewish suffering and resilience. Their art, while deeply rooted in Jewish experiences, mirrored the allegorical and dramatic modes prevalent in [[Christian art|Christian painting]], responding to the artistic and ideologies of the time. An example being Hirszenberg’s works, such as "Golus" and "Czarny Sztandar" (The Black Banner, 1907, Jewish Museum, New York), used Christian allegories to communicate broader themes of exile, suffering, and redemption, embodying the tension between death and resurrection characteristic of Christian imagery.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Jewish Museum |url=https://thejewishmuseum.org/index.php/collection/19689-the-black-banner |access-date=2024-03-28 |website=The Jewish Museum}}</ref><ref name=":5" /> |

||

== Modern period == |

== Modern period == |

||

Revision as of 20:36, 12 July 2024

Jewish art, or the art of the Jewish people, encompasses a diverse range of creative endeavors, spanning from ancient Jewish art to contemporary Israeli art. Jewish art encompasses the visual plastic arts, sculpture, painting, and more, all influenced by Jewish culture, history, and religious beliefs.

Jewish artistic expression traces back to the art of the ancient Israelites in the Land of Israel, where it originated and evolved during the Second Temple Period, influenced by various empires. This artistic tradition underwent further development during the Mishnaic and Talmudic eras, reflecting cultural and religious shifts within Jewish communities. With the dispersion of Jews across the globe, known as the Jewish diaspora, artistic production persisted throughout the millennia, adapting to diverse cultural landscapes while retaining distinct Jewish themes and motifs.

Until the emancipation, Jewish art was mostly centered around religious practices and rituals. Following the emancipation in the early modern period, Jewish artists, notably in Europe began to explore different themes, with different levels of connection to religious art. Notably, Jews in France, some of whom from fleeing from Eastern Europe, produced at times modernist art of completely secular nature. Later in the first half of the 20th century, a group composed mainly of these Eastern European Jews fleeing from persecution were known as the School of Paris.

From the mid to late 20th century, following The Holocaust and the immigration of Jews to modern Israel, Israel re-emerged as a center of Jewish art while Europe declined in its importance as a center of Jewish culture.

Second Temple period and late antiquity

In the Second Temple period, Jewish art was heavily influenced by the Biblical injunction against graven images, leading to a focus on geometric, floral, and architectural motifs rather than figurative or symbolic representations. This artistic restraint was a response to the Hellenistic cultural pressures that threatened Jewish religious practices, notably the imposition of idolatry. Symbolic elements like the menorah and the shewbread table were sparingly used, primarily reflecting their significance in priestly duties.[1][2]

However, the rise of Christianity and its establishment as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire marked a turning point in Jewish artistic expression. This period, known as Late Antiquity, witnessed Jewish communities gradually incorporating symbolic motifs into their synagogal and funerary art. The expansion of these symbols beyond the menorah and the shewbread table to include other ritual objects and emblems signified a broader expression of Jewish identity. This shift in cultural representation aimed to affirm Jewish faith and community following the rise of Christian dominance in the Mediterranean region, making symbols like the menorah emblematic of national identity as well as religious faith.[1][2]

The menorah, initially a representation of priestly duties in the Second Temple, evolved into a central symbol of Jewish identity, especially after the Temple's destruction. Its depiction in Jewish art, ranging from synagogue mosaics to catacombs, signified not only the religious importance of the Temple but also served as a distinguishing marker of Jewish places of worship and burial. Scholars debate the menorah's symbolism, with interpretations ranging from its seven branches representing divine light, the seven planets, or the days of the week, reflecting its integral role in both daily rituals and as a symbol of Judaism itself.[1][2]

The shewbread table, alongside other ritual objects such as the lulav, etrog, shofar, and flask, also played significant roles in Jewish art, marking the continuation of Temple traditions in diaspora communities. These objects, alongside depictions of the Temple, the Ark of the Scrolls, and the Ark of the Covenant, are part of an array of symbols used by Jewish communities to express and maintain their religious and cultural identity.[3][4][5]

Medieval Jewish art

During the medieval period (roughly the 5th to 15th centuries), Jewish communities continued to produce works of Jewish art, with most of the art centered around religious life, notably synagogues and religious texts.[6] Jewish scholars and texts, including works by luminaries like Rashi and Maimonides, often featured illustrations, some of which were crafted by artists who also served Christian clients, with notable connections between Jewish and Christian artists. The Florentine artist Mariano del Buono and the Master of the Barbo Missal, known for their work for Christian patrons, also created significant Jewish pieces.[6][7] Ritual objects such as Hanukkah lamps and kiddush cups, while prescribed by Jewish law, evolved in form and decoration over time, often mirroring the luxury items and aesthetic preferences of their Christian counterparts. This adaptability and integration are further evidenced in medieval synagogue architecture, which frequently borrowed elements from contemporary Christian buildings, as seen in the synagogues in Central Europe such as those in Regensburg and Prague, which incorporate Gothic styles and motifs.[6]

Interplay with Christianity

Artifacts from this era reflected the cultural exchanges between Jews and Christians, often as a result of intense theological dialogue and mutual curiosity between the two faiths. Christian scholars' efforts to learn Hebrew, challenge Jewish beliefs, or the portrayal of Jews and Jewish practices in Christian art with remarkable accuracy, suggest according to the Met, an interaction that was both intellectual and artistic. Objects such as the bronze menorah in the Cathedral of Essen and the head of King David from Notre-Dame de Paris are pointed to as examples of such artworks.[6]

Illuminated manuscripts, Haggadot

Jewish manuscripts during the medieval period, notably in medieval Spain were illuminated with visual imagery. The Sarajevo Passover Haggadah, originating in Northern Spain in the 14th century is a notable example.[8] The Golden Haggadah, originating in Catalonia exhibit Gothic and Italianate influences.[9]

Early modern period

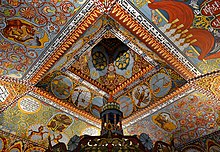

Jewish art continued to be projected through sacred spaces and religious art. The exteriors of synagogues, particularly notable in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, were often unassuming, with plain facades that concealed their richly decorated interiors. This contrast underscored a Jewish philosophical notion wherein the sacred resides hidden within the mundane, a concept mirrored in the architectural dichotomy between the exterior and interior of these religious buildings. The internal beauty of these synagogues, adorned with detailed paintings and elaborate designs, was in stark contrast to their modest exteriors, a dichotomy driven by a desire to avoid provoking Christian antagonism and adhering to restrictions imposed by Christian authorities, such as limitations on the height of Jewish religious buildings.[10]

Such restrictions led to innovative architectural solutions, including lowering the floors of synagogues to create a sense of increased interior height, a practice echoing the biblical verse "I call to you from the depths, O Lord" (Ps. 130:1). This approach not only adhered to the legal constraints but also enriched the spiritual ambiance of the synagogue space.[10]

In Italy, synagogues were often discreetly integrated into the upper floors of tenements within ghettos, their exteriors giving no hint of the opulent Baroque interiors within. This concealment extended beyond the synagogues' architecture to their urban placement, with some synagogues in Central Europe being hidden behind courtyards or other buildings, as seen in Dusseldorf and Vienna. This strategic concealment served both to comply with external regulations and to safeguard the sanctity and security of the Jewish worship space.[10]

Following the emancipation

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish culture |

|---|

|

The Napoleonic code written under Napoleon Bonaparte's French Empire liberated the Jews who had been restricted to ghettos and marginalized economically and politically.[11][12] The Napoleonic Code, also initiated Jewish emancipation across Europe, granting religious freedom to Jews, Protestants, and Freemasons. This act of liberation extended to territories conquered by the First French Empire, where Napoleon abolished laws that confined Jews to ghettos and restricted their rights. By 1808, he further integrated French Judaism into the state, establishing the national Israelite Consistory alongside recognized Christian cults, thereby formally acknowledging Jewish communities within French society for the first time.[11][12]

As Jews were emancipated and gained civil rights, they begun to integrate into mainstream society and work in occupations limited to them beforehand, Jews could become mainstream artists and were increasingly influenced by the prevailing cultural and artistic movements of their time.[13] These artists also began to create art beyond religious texts and spaces and engage in secular arts. This period also saw an increase in Jewish patronage of the arts.[13]

Eastern Europe

Early critics like Majer Bałaban viewed Jewish art broadly, including any object that exhibited “features of Jewish creativity,” while Abram Efros contended that Jewish artists should be recognized within the national contexts of their residence, arguing, “Jewish artists belong to the art of the country where they live and work”. Following the emancipation, figures such as Maurycy Gottlieb blurred traditional boundaries, integrating Jewish themes into a broader Christian iconographic tradition, laying foundational elements for Jewish genre painting. The late 19th and early 20th centuries with the rise of Jewish nationalism added an ideological dimension to Jewish art, with Jewish genre painting used by some as medium for expressing Zionist revival and the Jewish experience of exile.[14] Religious art and architecture manifested also in wooden synagogues in Eastern Europe which would eventually be destroyed by the Nazis in the Second World war.[15]

The works of artists such as Szmul Hirszenberg and Izidor Kaufmann showcased an interweaving of Jewish narratives with a universal moral vocabulary, drawing mainly on Christian allegories to depict Jewish suffering and resilience. Their art, while deeply rooted in Jewish experiences, mirrored the allegorical and dramatic modes prevalent in Christian painting, responding to the artistic and ideologies of the time. An example being Hirszenberg’s works, such as "Golus" and "Czarny Sztandar" (The Black Banner, 1907, Jewish Museum, New York), used Christian allegories to communicate broader themes of exile, suffering, and redemption, embodying the tension between death and resurrection characteristic of Christian imagery.[16][14]

Modern period

The School of Paris

The École de Paris, (the School of Paris in French) is a term coined in 1925 by art critic André Warnod, said to reprsent a diverse group of artists, many of Jewish origin from Eastern Europe, who settled in Montparnasse, Paris. Many of these Jewish artists arrived in Paris seeking artistic education and having fled from persecution, particularly in Eastern Europe. The École de Paris included notable figures such as Marc Chagall, Jules Pascin, Chaïm Soutine, Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel, Amedeo Modigliani, and Abraham Mintchine.[17][18][19] Their work often depicted Jewish themes and expressed deep emotional intensity, reflecting their experiences of discrimination, pogroms, and the upheavals of the Russian Revolution. The art of these artists, especially those of Eastern European origin is said to have reflected in expressionist works the plight and suffering of the Jewish people.[20][21] Despite facing xenophobia and criticism from some quarters, these artists played a central role in the vibrant artistic community of Paris, frequenting cafes, communicated in Yiddish and contributed significantly to its status as the capital of the art world.[22] The School of Paris ebbed away following the Nazi occupation of France and the Holocaust, during which several Jewish artists were murdered or died of disease. Several of the artists, such as Marc Chagall, dispersed to Israel and the United States.[22]

In Israel

In Israel, the influence of the École de Paris persisted from the 1920s through the 1940s, with French art and especially French Jewish artists continuing to shape the Israeli art scene for decades. The return of École de Paris artist Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel to Pre-Independence Israel in 1925 and the establishment of the Histadrut Art Studio marked the beginning of this influence. His students, upon returning from Paris, further amplified the French artistic influence in Pre-Independence Israel.[23] This period saw artists in Tel Aviv and Safed creating works that portrayed humanity and emotion, often with a dramatic and tragic quality reflective of Jewish experiences. Safed, one of the holy cities of Judaism, in particular, became a center for artists influenced by the École de Paris in the mid to late 20th century. Its mystical and romantic setting attracted artists like Moshe Castel and Yitzhak Frenkel Frenel, who sought to capture the city's spiritual essence and dynamic landscapes.[23][24]

Israel

In the early 20th century the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in 1906 was founded by Boris Schatz, blending European Art Nouveau with local artistic traditions. This period also saw the emergence of modern art movements and a shift towards a more subjective artistic expression, challenging the traditional confines of Bezalel's artistic doctrine. With the establishment of studios such as the Histadrut art studio[25] and exhibitions oriented toward modern art following the introduction of the influence of the École de Paris, Tel Aviv emerging as a cultural hub, in time replacing Jerusalem as the country's prominent art centre.[23][26]

During the early 20th century, artists began to settle in Safed, leading to the establishment of the Artist's Quarter of Tzfat which catalyzed what is at times referred to as a "golden age of art" in the city, spanning the 1950s through the 1970s. This era also saw the rise of significant art movements such as the Canaanite and New Horizons movements, further diversified the Israeli art scene.[27][28]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Hachlili 1998, pp. 343–344.

- ^ a b c Adler, Yonatan. "Representations of the Temple Menorah in Ancient Jewish Art in Light of Rabbinic Halakhah and Archaeological Finds". Hebrew.

- ^ Hachlili 1998, pp. 347–349.

- ^ Kanof, Abram (1982). Jewish Ceremonial Art and Religious Observance. New York: Abrams. ISBN 9780810921993.

- ^ N.Y.), Jewish Museum (New York (1955). Art of the Hebrew Tradition: Jewish Ceremonial Objects for Synagogue and Home. An Exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Commenorating the American Jewish Tercentenary; Arranged by the Jewish Museum of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, January 20, 1955 to February 27, 1955. Jewish Publication Society of America.

- ^ a b c d Holcomb, Authors: Barbara Drake Boehm, Melanie. "Jews and the Arts in Medieval Europe | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain: Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday By Katrin Kogman-Appel". www.psupress.org. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Verber, Eugen (1983). The Sarajevo Haggadah. Prosveta.

- ^ Narkiss, Bezalel (1969). Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts. Jerusalem, Encyclopaedia Judaica; New York Macmillan. p. 56. ISBN 0814805930.

- ^ a b c Goldman-Ida, Batsheva (2019-10-18), "Synagogues in Central and Eastern Europe in the Early Modern Period", Jewish Religious Architecture, Brill, pp. 184–207, ISBN 978-90-04-37009-8, retrieved 2024-03-28

- ^ a b "Napoleon was crowned on this day, revolutionizing Jews future in Europe". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b Ivry, Benjamin (2022-08-15). "The secret Jewish history of Napoleon Bonaparte". The Forward. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b The emergence of Jewish artists in nineteenth-century Europe. London: Merrell. 2001. ISBN 978-1-85894-153-0.

- ^ a b "YIVO | Painting and Sculpture". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Hubka, Thomas C. (1997), Hundert, Gershon David (ed.), "Jewish Art and Architecture in the East European Context: The Gwoździec-Chodorów Group of Wooden Synagogues", Jews in Early Modern Poland, Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Liverpool University Press, pp. 141–182, ISBN 978-1-874774-31-0, retrieved 2024-03-28

- ^ "The Jewish Museum". The Jewish Museum. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Princ, Deborah; Princ, Arthur; Princ, Boris; Taillan, Marie Boyé; Nieszawer, Nadine; Fogel, Paul; Morvan, Marianne Le (2020-04-07). Histoire des Artistes Juifs de l'École de Paris: Stories of Jewish Artists of the School of Paris. Independently Published. ISBN 979-8-6333-5556-7.

- ^ Roditi, Eduard (1968). "The School of Paris". European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe. 3 (2): 13–20. ISSN 0014-3006. JSTOR 41442238.

- ^ בעקבות אסכולת פריז. מוזיאון מאנה כץ - מוזיאוני חיפה. 2013. ISBN 978-965-535-027-2.

- ^ Barzel, Amnon (1974). Frenel Isaac Alexander. Israel: Masada. p. 14.

- ^ Voorhies, Authors: James. "School of Paris | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b Salmona, Macha Fogel / Paul (2021-11-25). "The Jewish painters of l'École de Paris-from the Holocaust to today". Jews, Europe, the XXIst century. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b c Hecht Museum (2013). After the School Of Paris (in English and Hebrew). Israel. ISBN 9789655350272

- ^ Ballas, Gila. The Artists' of the 1920 and Cubism. Israel.

- ^ טרכטנברג, גרסיאלה; Trajtenberg, Graciela (2002). "The Pre-State Jewish Bourgeoisie and the Institutionalization of the Field of Plastic Art / בין בורגנות לאמנות פלסטית בתקופת היישוב". Israeli Sociology / סוציולוגיה ישראלית. ד (1): 7–38. ISSN 1565-1495.

- ^ Barzel, Amnon (1987). Art in Israel. Flash Art Books. ISBN 978-88-7816-029-3.

- ^ טרכטנברג, גרסיאלה; Trajtenberg, Graciela (2005). בין לאומיות לאמנות: כינון שדה האמנות הישראלי בתקופת היישוב ובראשית שנות המדינה (in Hebrew). הוצאת ספרים ע״ש י״ל מאגנס, האוניברסיטה העברית. ISBN 978-965-493-227-1.

- ^ Benderly, Arieh (2000). From Bloom to Camila (in Hebrew). א. בנדרלי.

Sources

- Hachlili, R. (1998). Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1 The Near and Middle East. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29404-2. Retrieved 2024-03-29.