Workington: Difference between revisions

→The settlement where the River Derwent flows into the Solway Firth: insert wiki links |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===The settlement |

===The settlement where the River Derwent flows into the Solway Firth of the Irish Sea=== |

||

At the height of the [[Ice Age]] the central part of the modern [[Irish Sea]] was probably a long freshwater lake. As the ice retreated 10,000 years ago the lake reconnected to the [[Atlantic Ocean]], becoming [[brackish]] and then fully [[saline]] once again. |

At the height of the [[Ice Age]] the central part of the modern [[Irish Sea]] was probably a long freshwater lake. As the ice retreated 10,000 years ago the lake reconnected to the [[Atlantic Ocean]], becoming [[brackish]] and then fully [[saline]] once again. |

||

Revision as of 15:15, 28 October 2009

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| Workington | |

|---|---|

| Population | 19,884 |

| OS grid reference | NX996279 |

| • London | 259 miles (417 km) SE |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WORKINGTON |

| Postcode district | CA14 & CA95 |

| Dialling code | 01900 & 01946 |

| Police | Cumbria |

| Fire | Cumbria |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Workington is a town and port on the west coast of Cumbria, England at the mouth of the River Derwent.[1] Lying within the borough of Allerdale, Workington is 32 miles (51.5 km) southwest of Carlisle, 7 miles (11.3 km) west of Cockermouth, and 5 miles (8.0 km) southwest of Maryport.

Historically a part of Cumberland, the area around Workington has long been a producer of coal, steel and high grade iron ore.

Workington is the seat of Allerdale Borough Council, which is one of three borough councils in Cumbria. Tony Cunningham is the local MP for the constituency of the same name that includes other towns in the hinterland of Workington.

Workington is twinned with Selm in Germany and Val-de-Reuil in France.

History

The settlement where the River Derwent flows into the Solway Firth of the Irish Sea

At the height of the Ice Age the central part of the modern Irish Sea was probably a long freshwater lake. As the ice retreated 10,000 years ago the lake reconnected to the Atlantic Ocean, becoming brackish and then fully saline once again.

Archaeological evidence, in the form of stone-age artefacts, indicate that people were living at the mouth of the River Derwent thousands of years before it got its present name. In ancient times, the seafaring settlements around the Irish Sea formed a larger and more cohesive community than those formed by settlements linked over land by poor tracks or roads. Rivers, like the River Derwent, were major highways into the Lake District. The poor transport system over land meant that the area we now call West Cumbria was more isolated from most of England than it was from the Isle of Man, the Scottish isles, and the coasts of Ireland, Wales and Cornwall.

Roman Times (AD 79-410)

Between 79 and 122, Roman forts, mile-forts and watchtowers were established down the Cumbrian coast.[2] They acted as coastal defences against attacks by the Scoti in Ireland and by the Caledonii, the most powerful tribe in what we now call Scotland.[3] The 16th century book, Britannia, written by William Camden describes ruins of the coastal defences at Workington:

From thence some thinke there was a wall made to defend the shore in convenient places, for foure miles or there about, by Stilicho the potent commander of the Roman state, what time as the Scots annoyed these coasts out of Ireland. For thus speaketh Britaine of herselfe in Claudian:

'And of me likewise at hands (quoth she) to perish, through despight

Of neighbour Nations, Stilicho fensed against their might

What time the Scots all Ireland mov’d offense armes to take.

There are also, as yet, such continued ruins and broken walles to be seene as farre as to Elne Mouth...[4]'

The fort, now known as Burrows Walls, was established on the north bank of the mouth of the River Derwent, near present day Siddick pond and Northside. Another fort or watchtower would have been on How Michael to the south side of the river, near present day Chapel bank.[5] In 122, the Romans begin building Hadrian's Wall from Bowness on the Solway Firth to Wallsend on the North Sea. The discovery of a Roman fort around the parish church in Moresby to the south, and fortifications to the north at Risehow (Flimby), Maryport and Crosscannonby support the argument that the coastal wall extended down the whole Solway coast and formed a key part of the Empire's defences.

For many years Burrow Walls was believed to be the fort Gabrosentum or Gabrocentio, found in The Notitia Dignitatum for Britain, which lists several military commands (the Dux Britanniarum, the Count of the Saxon Shore (Comes Litoris Saxonici per Britannias) and the Comes Britanniarum). The word Gabrocentum has its origins in the Welsh or Ancient British gafr meaning "he goat" and the word hynt (set in Old Irish) meaning "path".[6] Today, many scholars believe it is more likely to be the fort known as Magis.[7]

Origin and spelling of the name Workington

The name Workington, is believed to be derived from three Anglo-Saxon words; Weorc (most probably a man's name), ingas (people) and ton (settlement/estate/enclosure).[8] The settlers were a group of people whose leader called himself Weorc. It is an unusual name but not unique: Worksop is another placename believed to be derived from the same personal name. Over 1000 years ago, the original inhabitants of the land would have called themselves Weorcingas (Weorc's people) and the settlement Weorcinga tun (estate of the Weorcingas). Other local place names with similar origins are Harrington, Distington and Frizington.[9]

The Old English word Weorc meant accomplishment, achievement, act, action, deed, labour, measure, move, work:[10] possibly work linked to a fortification.[11] In Old English, weorc was a noun and weorcan (or wyrcan) a verb, which meant to do, make, produce, prepare, perform, construct, use (tools); constitute; amount to; to strive after; to deserve, to gain and to win.[12]

Over a period of almost 1000 years, the town’s name has been written in at least 80 different ways:[13] 1100 Wirchington; c1125 Wirkynton; c1130 Wirchintuna; c1150 Wirchinghetona; 1150 Wirchingetona; 1150 Wirchintona; c1150 Wirchintuna; 1160 Wyrchynton; c1180 Wirkintun; c1180 Wirkintuna; c1200 Wirkyngtona; 1190 Wirkeinton; 1200 Workinton; 1211 Wirketon'; 1240 Wirgington; c1202 Wyrkintun; c1200 Wirkingtun; 1275 Wrykinton; 1277 Wyrkingthon; 1277 Wyrkyngtona; 1278 Wyrkinton; 1278 Wyrkyngton; 1279 Wrykington; 1297 Wyrkington; c 1250 Wurcingtun; c1300 Wirkingtona; 1298 Wirkington; 1299 Werkenton; 1300 Wirkinton; 1300 Wirkyngton; 1350 Workyngton; 1405 Werkyngton; 1512 Wrykynton; 1564 Workington; 1565 Wyrchyngton; 1566 Wurkington; 1568 Wurkinton; 1569 Woork-kington; 1569 Woorkyngton; 1573 Wynkinton; 1576 Workinto; 1576 Wyrkenton; 1611 Werkinton; 1625 Werkington; 1638 Warkington; 1691 Wirkintonae; 1720 Warkinston; 1772 Workenton; 1778 Workintou; 1860 Wyrekinton; 1869 Wurki'ton; 1876 Workiton; 1901 Wyrekenton; 1901 Wyrekington and Wokington. Online today: Wuckington, Wukington, Wuckinton, Wukinton, Wukintun, Wukiton, Wukitun, Wukintn, Wukkitn, Wukkiton, Wucki'n, Wuki'n, Wukki, Wuki, Wkntn, Wktn and Wkn.[14]

Even though the spelling of the town's name has varied over the centuries, the letters wkntn are nearly always present. The variation in spelling is understandable, because for many centuries, most people could not read or write, and few communications were written down. The spellings in historic documents were often decided by visitors, especially officials, monks and later mapmakers (cartographers), who wrote down the names as they believed they had been spoken to them. Due to the practical problems in map-making, people frequently lifted material from earlier works, without either checking accuracy or giving credit to the original cartographer. Today, when speaking in dialect, locals say they come from Wukitn or Wuki'n, with the emphasis on Wuk.

So, the word Weorc has been written down as Wirch, Wirk, Wyrch, Work, Wirg, Wyrk, Wryk, Wurc, Werk, Wurk, Woork, Wynk, Wark, Wyrek, Wuck, Wuk and Wk.[15][16] Weorc is the West Saxon form of the name, and therefore the Old English form that most language experts would quote, because the centre of power and literacy was in the southwest of England at the time of the Danish wars. The 'eo' letters in Weorc can confuse people, but for pronunciation purposes the 'o' may be ignored; but it can help when trying to produce a strong rolling r sound. Anglo-Saxons would have strongly pronounced the r.

In 1533, John Leland (antiquary) believed the town derived its name from the River Wyre. But the River Wyre has its origins at Ellerbeck, Hunday and Distington and actually enters the Solway at Harrington.[17] In 1688, William Camden quotes Leland, writing that the Wyre "…falls into the Derwent at Clifton…",[18] but it does not.

St Cuthbert and the Lindisfarne Gospels (c880)

In 875 the Danes (also called Vikings and Norsemen) invaded the north-east coast of England. They took the monastery on the island of Lindisfarne. Some of the monks fled, carrying with them St Cuthbert's body and a richly decorated copy of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

During his life, St Cuthbert had been a regular visitor to Cumbria, including the Derwent valley and Borrowdale, where he visited his hermit friend on an island in Derwentwater. The group, now carrying his body and the Gospels, avoided the invaders by moving around the north of England and southern Scotland before arriving in West Cumbria. They probably travelled down the River Derwent to the river mouth. It is believed that there was a religious community of monks, with links to Lindisfarne, living and working where St Michael's Church stands today. At that time, higher sea levels would mean the community may have lived on an island south of the river's mouth. The Lindisfarne monks attempted to cross the Solway Firth to Ireland in a boat, but a strong storm blew up and the Lindisfarne Gospels were lost overboard. The monks were forced back to shore. Tradition says that the Gospels, which were probably inside a wooden box, were discovered water-stained but safe in the sea near Candida Casa on the Isle of Whithorn.

After seven years' wandering with Cuthbert's body the monks found a resting place at Chester-le-Street and later in Durham Cathedral. The Lindisfarne Gospels saved from the waters of The Solway Firth are now on view in the British Museum. The British Library calls them "The Pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon Art" even though many other decorated manuscripts exist in museums around Europe. Now everyone can read the Gospels online on the British Library web site.[19]

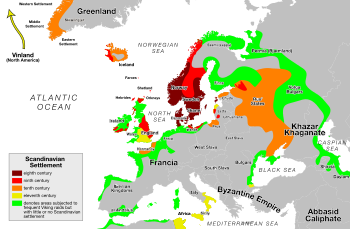

The Vikings or Norsemen

The discovery of a Viking sword at Northside (West Seaton) during roadworks established the river mouth as a port of call or settlement. The sword is thought to be part of a burial,[20] in an area which has subsequently been shown to be rich in evidence of Viking period activity.[21]

The Vikings, or Norsemen, sailed over most of the North Atlantic, reaching south to North Africa and east to Russia, Constantinople and the Middle East, as looters, traders, colonists, and mercenaries. Vikings under Leif Eriksson, heir to Erik the Red, reached North America. The Norsemen or Northmen were also known as Dene (Danes) by the Anglo-Saxons.

While much of England was conquered by the Vikings, the Brythons and Anglo-Saxons of Cumberland, Cornwall, Wales and much of present-day Scotland remained independent. We do not know for certain why these areas developed side-by-side with invaders who had conquered most other areas of the British Isles.

The coming of the Vikings (Norsemen) did not result in the renaming of Anglo-Saxon settlements on the Cumbrian coastal plain, but many place names in the valleys of the Lake District indicate that Scandinavians settled and named both significant and minor landmarks. Viking (Norse) strongholds like the Isle of Man and their Kingdom of Dublin represented a significant, long term Scandinavian presence in the Irish Sea. The settlement of the Northmen on the coast of Francia became Normandy, home of the Normans, who sailed north in 1066.

King Dunmail, last ruler of the Kingdom of Cumberland (945)

The Kingdom of Cumberland existed until 945. King Dunmail, Cumberland's last king, is a figure of both history and legend. Warriors and supporters would have been recruited from around his lands. In 945, the combined armies of King Edmund I of England and King Malcolm I of Scotland conquered the independent Kingdom of Strathclyde. They then defeated the Cumbrian forces, at Dunmail Raise between Grasmere and Thirlmere, and the Kingdom of Cumberland became part of Scotland or Alba.

This historical conflict is the subject of a legend with strong echoes of the King Arthur myth of The Once and Future King. In 1873 the ballad King Dunmail was printed in the Lays and legends of the Lakes Country, which brought this part of Cumbrian history to a wider audience.[22][23] In 1975, Workington-based Fellside Records, released Paul and Linda Adams' version of King Dunmail on the album 'Far over the Fell'.[24][25]

In 1054, a very large English army invaded King Macbeth's Scotland. The campaign led to a bloody battle in which 3,000 Scots and 1,500 English died. The result of the invasion was that one Máel Coluim, son of the king of the Cumbrians was restored to his throne, i.e., as ruler of the kingdom of Strathclyde. The River Derwent formed the border with England during King Macbeth's reign.

Why is Workington not mentioned in the Domesday Book? (1086)

Cumberland was part of Scotland when the Normans invaded in 1066 and also 20 years later when the Domesday Book was completed. The book records the great survey of England ordered for William the Conqueror. He sent men all over England to each shire to find out what and how much each landholder had in land and livestock, and what it was worth. Most of Cumberland and Westmorland are missing because they were not conquered until some time after the survey.

The First War of Scottish Independence (1296-1328)

The First War of Scottish Independence started with the English invasion of 1296 and ended with Scottish victory at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. In 1328, the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton signed by Robert the Bruce and the Parliament of England acknowledged Scottish Independence, '...divided in all things from the realm of England, entire, free, and quit, without any subjection, servitude, claim, or demand'. The Curwens, who were Lords of the Manor of Workington, were heavily involved in this war. The Curwen family motto, "Si je n'estoy" ("If I had not been there"), is said to come from the words of Sir Gilbert (ii) de Curwen, whose late arrival with fresh troops recruited from his estates turned the course of the Battle of Falkirk (1298), giving King Edward victory.[26] It has been suggested that Gilbert waited until he knew who looked like winning before joining battle, because he had family supporting both sides in the conflict. It was at this battle that William Wallace was defeated and subsequently executed. It forms the storyline of the Hollywood film Braveheart.

Edward I, and monarchs who reigned after him, used the royal right of purveyance and conscription to acquire men and materials for his campaigns. This right affected the living standards of his subjects, especially in areas prone to conflict like the Cumberland.

In 1306 Robert the Bruce was crowned King Robert I of Scotland. In 1307, The Calendar of Patent Rolls of King Edward I of England records his preparing for war against Robert the Bruce. He requests lords of the manor to provide ships, barges and 'find them in men and necessaries' to continue the war. It read:[27]

...to get ready empty ships and barges at Skymburneys, Whitothavene and Wyrkinton, and elsewhere by the shore in that county, and find them in men and necessaries to go to the parts of Are to repress the malice of Robert de Brus and his accomplices. Writ de intendendo in pursuance to the men of that county...Appointment of John du Luda, as captain and governor of the fleet from the port of Skynburnesse, Whitothavene and Wyrkinton...[28]

The Second War of Scottish Independence (1333-1357)

The Second War of Scottish Independence effectively began in 1333, when Edward III of England overturned the 1328 Treaty of Northampton, under which England recognised the legitimacy of the dynasty established by Robert Bruce. Edward was determined to support the claim of Edward Balliol, the son of the former king, John Balliol, over David II, Bruce's son and heir. English involvement in Scotland was also to be one of the factors leading to the outbreak of the Hundred Years War with France in 1337. Once again the Curwens, Lords of the manor of Workington, were expected to provide support and troops to fight in both Scotland and France, and protect their vulnerable borderlands.

The Hundred Years' War with France (1337-1453)

The Hundred Years' War was fought between two royal houses for the French throne. The two primary contenders were the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet. The House of Valois claimed the title of King of France, while the Plantagenets from England claimed to be Kings of France and England. Plantagenet Kings were the 12th century rulers of England, and had their roots in the French regions of Anjou and Normandy. The Curwens and their troops were expected to support the English kings in all their campaigns, to keep royal favour and retain their lands in England. Sir Gilbert (iii) de Curwen (c. 1296-1370), received his knighthood on the battlefield at Crecy in 1346. He and his men fought alongside King Edward III of England as he attempted to seize the French throne after the death of Charles IV.[29]

In 1379, Sir Gilbert (iv) de Curwen (died c. 1403) received a licence to fortify and crenellate the pele tower built by his father in Workington in 1362. Sir Gilbert is believed to have died in 1403 during the great pestilence (plague), which also killed his first son, Sir William (i), who inherited his title.[29] The Black Death is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of Europe's population, reducing the world's population from an estimated 450 million to between 350 and 375 million by 1400. This has been seen the cause of a series of religious, social and economic upheavals which profoundly affected the course of European history.

The Peasants' Revolt took place in 1381, during the reign of the young King Richard II. It was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history, but also the best documented popular rebellion ever to have occurred during medieval times. Although a failure, the uprising is significant because it marked the beginning of the end of serfdom in medieval England. It led to calls for the reform of feudalism and an increase in rights for the serf class. This would have threatened the power-base of all major landowners, including the Lords of the Manor of Workington. How this affected Cumberland in general and Workington in particular is yet to be fully documented.

Curwen tradition believes that at least one member of the family fought with Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. The roll mentions a John Werkyngton.[30][31] This very unusual spelling matches with '...the manor of Werkyngton, co. Cumberland...' written in King Henry's Patent Rolls in 1405.[32] John may have been a younger Curwen son, a cousin or a man of standing from the community. The names of the thousands of archers and ordinary private soldiers are not on the roll.

In 1428, Henry VI of England, granted Sir Christopher (ii) de Curwen (1382-1453), the Castle and land of Cany and Canyell in Normandy, France as a reward for "good service". In 1429, he returned to northern England to fight an invasion by the Scots. In 1442, he oversaw the truce between Henry VI of England and King James II of Scotland. The lands in Normandy were lost to the French in 1450.[33] Sir Christopher and his wife, Elizabeth Huddleston, are buried inside St Michael's Church, under a heavily carved tombstone bearing their effigies.

Sir Thomas (iv) Curwen (c. 1494-1543) married Agnes, daughter of Sir Walter Strickland and great-granddaughter of Anne Parr. The royal blood of the Plantagenets came to the Curwen house.. according to the book Papers and Pedigrees by William Jackson (1892).[33]

The Wars of the Roses (1455-1485)

The Wars of the Roses were a series of bloody dynastic civil wars between supporters of the rival houses of Lancaster and York for the throne of England. Throughout this period landowners and powerful families had to decide which side they favoured. The Curwens appear to have provided material and physical support to both sides during the war. Sir Thomas (ii) Curwen (c. 1420-c. 1473) was commissioned by King Edward to mobilise his forces to resist the rebellion of Richard, Duke of York at the beginning of the Wars. During the Wars the throne changed hands between the two houses and most able-bodied men, especially in the north of England, would have been forced into the conflict. King Edward IV of England of the House of York, later granted honours to the Curwen family, in acknowledgement of "great and gratuitous service".[34] The war ended with the victory of the Lancastrians who founded the House of Tudor, which subsequently reigned over England and Wales for 118 years.

Scottish pirates kill the crew of a Workington bound ship

Philip II of Spain had been co-monarch of England until the death of his wife Mary I in 1558. A devout Roman Catholic, he considered the Protestant Elizabeth a heretic and illegitimate ruler of England. He supported plots to have her overthrown in favour of her Catholic cousin Mary, Queen of Scots. England used privateers to great effect and suffered much from other nations' privateering and piracy.

In 1566, Queen Elizabeth was encouraging mining of metal ores in the area around Keswick. It appears that the 'Samuel', a new ship built in Bristol, was employed to supply materials to and bring ore from the mines. Workington was growing, and a stretch of the shore was purchased to unload timber brought from Ireland to help smelt ore. England was extremely short of metals and weapons technology, and the ore was primarily to be used for cannon and other weaponry[35]

...the (ship) Samuel of Bristol...whereof one Edward Stone was master and partie owner, and put the same to the sea, fraighted with their goodes and merchandizes the 20th September last past to traffique with the same to a place called Wurkington in the North parties of our realm, near unto our citie of Carlisle, the said ship being in her way towardes the said place was dryven by force of weather and tempest to the coast of Scotland to a place called the Keyles', and there ryding at an ancre was boorded by certaine Scottishmen, who fayning themselfes to be merchants and cum onely to see what merchandizes was in the ship, most cruelly did murdre the said Master with all his companie except two that kept themselfes in secret places of their ship until the furye of thies murderers was asswaged, and so toke both ship and goods as their owne...[36]

Mary Queen of Scots escapes to Workington (1568)

In 1568, Mary wrote a letter from Workington Hall to Queen Elizabeth I of England. After the defeat of her forces at the Battle of Langside and disguised as an ordinary woman, Mary, Queen of Scots[37] crossesdthe Solway Firth and landed at Workington. She spent her first night in England as an honoured guest at Workington Hall. On 18 May 1568, Mary was escorted to Carlisle Castle after spending a day at Cockermouth. She was 25 years old.[38]

Elizabeth I emancipates the last Serfs (1574)

In England, the end of serfdom began with Peasants' Revolt in 1381 was fully completed when Elizabeth I freed the last remaining serfs in 1574. The relationship between the monarch, landowners and the people living on the lands was radically changed forever. The changes to manorialism or feudalism weakened the power and control of the landowners in England. In principle, the Curwen's of Workington could no longer use forced labour on the land and conscript locals into their private forces. Some historians equate the significance of this event with the abolition of slavery in the 17th century. As primarily an agricultural county, the impact throughout Cumberland would have been significant. There were native-born Scottish serfs until 1799.

William Camden's Britannia (1586)

In 1577, William Camden began to write his book Britannia, a county-by-county description of Great Britain and Ireland. Rather than writing a history, Camden wanted to describe in detail the country as it was then. His stated intention was "to restore antiquity to Britaine, and Britaine to its antiquity." Written in Latin and first published in 1586, it proved very popular.[39] This extract from Philemon Holland's English translation of Britannia(1610)[40] describes Wirkinton:

...Derwent, having gathered his waters into one streame, entreth into the Ocean at Wirkinton, a place famous for taking of Salmons, and now the seat of the ancient family of the Curwens Knights, who fetch their descent from Gospatric Earle of Northumberland, and their surname they tooke by covenant and composition from Culwen a family in Galloway, the heire whereof they had married; and heere have they a stately house built Castlelike, and from whom (without offence or vanity be it spoken) my selfe am descended by the mothers side.

He then goes on to describe the coastal defences described in this article in the section on the Romans.[4]

John Christian Curwen (1756-1828)

The greatest strides in Curwen initiative occurred during the lordship of John Christian Curwen. Workington changed radically both economically and socially, during the period when John Christian was lord of the manor (1783-1828).[41] A Curwen through his mother's side, ...he is the man who stands out...who must rank as one of the most interesting and progressive of Cumbrians of his day.[42] He was Member of Parliament for Carlisle from 1796 to 1812 and from 1816 to 1820, following this with a period as member for Cumberland from 1820 to 1828. He made a national mark in his campaigns for reform of the Corn Laws and Agrarian Laws, and for Catholic emancipation especially the Relief Act of 1791. His influence was such that he was offered peerages by both Addington and Castlereagh but he turned them down. His practical interest in agricultural reform can be traced in the proceedings of the Workington Agricultural Society, of which he was founder-president.[43] Cumbrian archive records contain reports on Curwen's experimental farm at the Schoose, and on such other items as the estate he purchased between Windermere and Hawkshead, Lancashire, in order to encourage forestry. By planting over 800,000 trees around Lake Windermere he transformed that area of the Lake District. A active supporter of the abolition of slavery his friend and party activist William Wilberforce spent time with John Christian on Belle Isle.

To modern eyes, however, one of the most interesting of his projects was his introduction of social security and mutual benefit schemes for his farm and colliery workers.[44]

Education

Key education developments include: Patricius Curwen's school on High Street (1664-1813), becoming the 'National' school in Portland Square (est. 1813), Wilson Charity School (1831-1967) on Guard Street which became the Higher Standard Council School (locally called 'Guard Street', St John's School (1860-) on John Street, St Michael's School (1860- date), Lawrence Street School (Marshside) (1874-1979), Victoria School, Northside School (1878-1977), Siddick School (1902-1967), Seaton School,[45] Bridgefoot School, Westfield School, Moorclose School (1967-1984), Newlands School (1909-1984), Workington School Grammar School/Technical and Secondary School (1912-1984) , Lillyhall School at Distington (1961-84), Distington School, St Joseph's Roman Catholic High School (1929-date), Derwent Vale School at Great Clifton, Ashfield School, Salterbeck School (1961-1981), Southfield School (1984-date),[46] Stainburn School (1984-date), Beckstone Primary School at Harrington.

Geography

Workington lies astride the River Derwent, on the West Cumbrian coastal plain. It is bounded to the west by the Solway Firth, part of the Irish Sea, and by the Lake District fells to the east. Workington comprises various districts, many of which were established as housing estates.

North of the river these districts include Seaton, Barepot, Northside, Port and Oldside. On the south side are the districts of Stainburn, Derwent Howe, Ashfield, Banklands, Frostoms (Annie Pit), Mossbay, Moorclose, Salterbeck, Bridgefoot, Lillyhall, Harrington, High Harrington, Clay Flatts, Kerry Park, Westfield and Great Clifton. The Marsh and Quay,[47] a large working class area of the town around the docks and a major part of the town's history, was demolished in the early 1980s. Much of the former area of the Marsh is now covered by Clay Flatts industrial estate.

Economy

Iron and steel

The Cumbria iron ore field lies to the south of Workington, and produced extremely high grade phosphorus-free haematite. The area had a long tradition of iron smelting, but this became particularly important with the invention by Sir Henry Bessemer of the Bessemer process, the first process for mass production of steel, which previously had been an expensive specialist product. For the first 25 years of the process, until Gilchrist and Thomas improved it, it required phosphorus-free haematite. With Cumbria as the world's premier source of this, and the local coalfield also available for steel production, the world's first large-scale steel works was opened in the Moss Bay area of the town. The Bessemer converter continued to work until 1977, the world's first and last commercially operated Bessemer converter. The Moss Bay steel works were themselves closed in 1982, despite having received significant infrastructural investment and improvement almost immediately prior to the closure.

During World War II, a strategically important electric steel furnace which produced steel for aircraft engine ball bearings was relocated to Workington from Norway to prevent it falling into Axis hands.

Workington was the home of Distington Engineering Company (DEC), the engineering arm of British Steel Corporation (BSC), which specialised in the design of continuous casting equipment. DEC, known to the local people as "Chapel Bank", had an engineering design office, engineering workshops and a foundry that at one time contained six of the seven electric arc furnaces built in Workington. The seventh was situated at the Moss Bay plant of BSC. In the 1970s, as BSC adapted to a more streamlined approach to the metals industry, the engineering design company was separated from the workshops and foundry and re-designated as Distington Engineering Contracting. Employing some 200 people, its primary purpose was the design, manufacture, installation and commissioning of continuous casting machines.

One offshoot of the steel industry was the production of steel railway rails. Workington rails were widely exported and a common local phrase was that Workington rails 'held the world together'. Originally made from Bessemer steel, following the closure of the Moss Bay steel works (ending actual steel production in Workington) steel for the plant was brought by rail from Teesside. The plant was closed in August 2006, the end of Workington's long and proud association with the steel works. However welding work on rails produced at Corus' French plant in Hayange continued at Workington for another two years, as the Scunthorpe site initially proved incapable of producing rails adequately.

After coal and steel

After the loss of the two industries on which Workington was built, coal and steel, Workington and the whole of West Cumbria are something of an unemployment blackspot. Industries in the town today include chemicals, cardboard, the docks (originally built by the United Steel Co, they have for some time faced an uncertain future), waste management and a relatively novel industry, recycling old computers for export, mainly to poorer countries. The town also houses the British Cattle Movement Service, a government agency set up to oversee the U.K. beef and dairy industry following the BSE crisis in Britain. It is located in former steelworks offices. Many Workington residents are employed outside the town in the nuclear industry located in and around Sellafield, West Cumbria's dominant employment sector. None of the nuclear industry is located in Workington itself: much of it is based around Whitehaven.

Vehicles

Workington formerly manufactured 'Railbus' and 'Sprinter' type commuter trains and Leyland National buses. The Leyland National was based on an Italian design, which included an air conditioning unit mounted in a pod on top of the roof of the bus at the rear. Adapting the design for Britain, Leyland replaced the air conditioning unit with a heating unit. However, as hot air rises, much of the heat generated by the heaters was wasted as it escaped out of the top (most vehicle heaters are located low down in the vehicle). This design flaw in the National bus became infamous in the trade.

The 'Railbus' trains were based on the National bus design, designed as a cheap stopgap by British Rail. This initiative led to Workington's brief history of train manufacturing, the buses already being built there. The trains are generally considered to be badly designed, and are very uncomfortable to ride, especially on less-than-perfectly-smooth rail lines: the carriages tend to jump about much more than most trains, as they are not equipped with proper train bogies, but have two single axles per carriage (each train consists of two carriages), a cost-cutting design feature which has also caused problems with tight-radius corners on some lines. Some industry experts have also questioned their safety compared to other commuter train types, such as the Sprinter.

The former bus plant, located in Lillyhall, is now a depot for the Eddie Stobart road haulage company.

Transport

Workington is linked by the A596 road to Maryport and (via the A595 road) to Whitehaven, and by the A66 road to Cockermouth, the M6 motorway, Penrith and County Durham.

The town has bus connections to other towns and villages in West Cumbria, Penrith, Carlisle and Barrow-in-Furness.

The Cumbrian Coast Line provides rail connections to Carlisle and Barrow-in-Furness, with occasional through trains to Newcastle, Lancaster and Preston.

The nearest airports are Newcastle, Manchester and Glasgow, which can be reached by road and rail.

The Coast to Coast Walk begins in West Cumbria, on the shores of the Irish Sea. Walkers may choose to begin at St Bees, Whitehaven or Workington. The route then crosses the coastal plain, the Lake District, the Pennines and the North York Moors, and ends on the North Sea coast at Robin Hood's Bay in Yorkshire. But some walkers instead start from the east coast, preferring to have the Lake District as the climax of their walk. The cycling alternative, the Sea to Sea Cycle Route, may also begin in the surf at Workington's sea shore. The Reiver's Route passes through the town. West Cumbria is an interesting diversion from the Cumbria Cycle Way.

Cultural festivals

Seaton and Moss Bay Carnivals

Valentine rock

Valentine Rock is the 19 band charity music festival in Workington, Cumbria in England, that will take place on the 19th of September[1]. To be staged at the Ernest Valentine Ground home of Workington Cricket Club. The festival site is the picturesque High Cloffock near the River Derwent, overlooked from the new town centre[2]. Artists on the bill include: The Chairmen, Novellos, With Lights Out, Volcanoes, Breed, Colt 45, Relics, Telf, Thir13een, Slagbank, Hangin' Threads and Hand of Fate[3]. All profits will go to the RNLI and West Cumberland Lions.[48]

Paint the town red

In 2008, The Paint Your Town Red Festival invited Liverpool comic and actor Ricky Tomlinson, to top the bill. Described as 'The biggest free festival in Workington’s history', it welcomes everyone adopting red as their colour for the day. A special atmosphere is created as all town centre shops extend opening hours. The 2008 festival included a free children’s fun fair in Vulcan Park and stage and street entertainnment. Soul legend, Jimmy James and his Soul Explosion, were the big name to perform. Keswick’s 'Cars of the Stars' Museum, provided a cavalcade mini cars with a stunt driving display. Appearances by famous cars like Herbie the Beetle, the Back to the Future De Lorean and Kit from Knightrider of the 1980, made the day special for old and young. Dearham Band and the all-girl band Irresistible also made an impressive appearance.

Sports

Uppies and Downies

Workington is home to the ball game known as Uppies and Downies, a traditional version of football, with its origins in Medieval football, Mob football or an even earlier form.[49][50][51][52] Since 2001, the matches have raised over £75,000 for local charities.[53][54][55] An Uppies and Downies ball is made from four pieces of cow leather. It is 21 inches (53 cm) in circumference and weighs about two and a half pounds (1.1 kg). Only three hand-made balls are produced every year and each is dated.[56] Some players from outside Workington take part, especially fellow West Cumbrians from Whitehaven and Maryport. As with much of the town's sporting history, some of the best and most accurate records are to be found in the local newspapers, The Evening Star and The West Cumberland Times and Star.

Football

Workington Association Football Club's home ground is Borough Park, situated on the Low Cloffolk on the south bank of the River Derwent. Formally a professional football team it now competes as non-League club. Popularly known as the 'Reds', they currently play in the Conference North. First formed in 1888 by Dronnies, the nickname used by locals for the Dronfield steelworkers and their families, who moved to Workington from 1882. It is estimated that about 1500 people made the move. The Dronnies brought the newly established rules of football with them. These rules for Association Football were established by the world's first soccer club, Sheffield Football Club.[57] Dronnies formed the nucleus of the original Workington FC in 1988.[58]

Rugby

The local professional rugby league team are former Challenge Cup winners Workington Town.

Bowling

There are two bowling greens in town, one in Vulcan Park and another on High Cloffolk south of the River Derwent. Teams and individuals from both greens compete in local, regional and national competitions.

Golf

Workington's first golf club was formed in 1893 and played north of the River Derwent near Siddick. Known as West Cumberland Golf Club, it used this nine hole course until the First World War when it closed. After the war the club reformed as Workington Golf Club and moved to the present Hunday location. Five-times Open Champion and renowned course architect James Braid was consulted on the layout. Considered 'one of the premier courses in Cumbria' it has been influenced by FG Hawtree[59][60] during the 1950s and by Howard Swan today.[61] Annual club championships are staged.

Speedway

Workington Comets are the town's professional speedway team,[62] which competes in the British Speedway Premier League.[63]

Before World War II racing was staged at Lonsdale Park, which was next to Borough Park, on the banks of the River Derwent. The sport did not return to the town until 1970, when it was introduced to Derwent Park by local entrepreneur Paul Sharp and Ian Thomas who is the present team manager (2009). In 1987, Derwent Park was a temporary home to the Glasgow Tigers (speedway) who briefly became the Workington Tigers prior to their withdrawal from the League. Speedway returned to Workington[64] and the team has operated with varying degrees of success, but in 2008, they won the Young Shield[65] and the Premier League Four-Team and Pairs Championships. An Academy team under the banner of Northside Stars, develops young riders who show potential at the Northside training track and may make future first teams.[66]

Cricket

Workington Cricket Club's home is the Ernest Valentine Ground, on the High Cloffock near the River Derwent and the town centre.[67] It is a thriving club with 3 senior teams and a growing junior section putting out 6 teams. It is affiliated to Cumbria Cricket League, Cumbria Cricket Board, Cumbria Junior Cricket League and the West Allerdale & Copeland Cricket Association. Coaches lead Cumbria Cricket Board Open Courses at the town's Stainburn School, which are open to Years 4/5/6, 7&8 and 9&10 students.[68]

Workington Cricket Club will also stage Valentine Rock, a 19 band charity music festival at the ground on the 19th of September.[69][70] With all profits going to the RNLI and West Cumberland Lions, it is a further expression of the progressive nature of one of the oldest sporting clubs in the town.

Angling

Workington and District Sea Angling Club takes part in regular monthly matches . It meets every month in the Union Jack Club, Senhouse Street, Workington. It also arranges tuition for its anglers.[71] Freshwater anglers are active on local rivers, especially the River Derwent.[72]

Athletics

Workington offers opportunities for track and field, triathlon, road running, cross-country, fell running and orienteering. All of its schools and clubs are affiliated to the Cumbria Athletics Association,[73] except orienteering which is organised through its own national federation.[74] Athletes tend to join clubs which concentrate on their particular discipline. Cumberland Fell Runners;[75] Cumberland Athletics Club;[76] Derwent and West Cumberland AC; Seaton Athletics Club; Workington Zebras AC and West Cumberland Orienteering Club[77] are the most popular at present.

Primary schools have a well organised inter-school programme.[78] Secondary schools focus especially on the Allerdale District School's Championships, which lead on to the Cumbria Schools Championships. The results of Cumbria's championships guide selection of the county teams to compete in the English Schools Athletic Association Championships. Over the years, Workington athletes have earned English Schools Championship honours.

Motorcycle road riding

There is a Cumbria Coalition of Motorcycle Clubs.[79] The West Cumbrian motorcycle club, The Roadburners.[80] was established 20 years ago and regularly attends local and national motorbike rallies, and charity road runs. It welcomes new members interested in multi cylinder machines.[81] The National Chopper Club also has local members.[82]

Notable people

- Freddie Cairns (1863-) - The self-styled Duke of Workington. A good-natured rag and bone man and 'constructor of paper jumping jacks and windmills',[83] which he sold on the streets from a basket hung around his neck. Freddie featured on Victorian black and white postcards as a significant Workington character. An endearing story of his wedding day adventures made the newspaper in 1895, indicating the level of local affection for the 'Duke'.[83]

- Dale Campbell-Savours, Baron Campbell-Savours (1943-) - Labour politician and Member of Parliament (MP) for Workington from 1979 to 2001.

- Thomas Cape M.B.E (1868–1947) - Labour politician and Member of Parliament (MP) for Workington from 1918 to 1945.

- Mark Cueto - English international rugby union player.

- Scott Dobie - Carlisle United and Scotland international footballer

- Troy Donockley - Renowned Workington born player of uillean pipes.

- Sir Joseph Brian Donnelly (UK diplomat) KCMG, KBE, CMG - Son of Workington steelworker, educated at Workington Grammar School and Oxford University.

- James Duffield (1835-1914) and Josiah Purser (1848-1928) - Responsible for moving the entire Dronfield steelworks (opened in 1873) to Workington in 1882. Both later served as Aldermen on Workington Borough Council.[84]

- Kathleen Ferrier CBE (1912–1953) - Won the prestigious Gold Cup at the 1938 Workington Musical Festival.[85]

- Colonel Darren Greene (1860 - 1941)

- Harold Goodall and Herbert Stubbs - World War 2 railwaymen notable for risking their lives to stop a burning ammunition wagon destroying a 57 vehicle train.[86]

- Fred Peart, Baron Peart Member of Parliament for Workington from 1945 to 1976. Fred was made a life peer in 1976, and served as Leader of the House of Lords and Lord Privy Seal.

- Gordon Preston (1925-) - Mathematician

- Bishop Desmond Sibbald

- James Alexander Smith VC (1881-1968) - Workington born soldier of the 3rd Battalion, Border Regiment during World War I.

- Joseph 'Joey' Thompson - English Senior Amateur Billiards Champion 1936, 1947 and 1948.[87]

- Workington Steelworkers of 1878 - Gold medal winners at the Exposition Universelle (1878) or Paris World's Fair[4]. The exhibits for Haematite pig iron, 'Bessemer' steel ingots (produced by the Bessemer process), castings, railway tracks and plates all won gold medals. This success led to international recognition and a significant increase in export orders.[88]

Regeneration

Town centre re-development

In 2006, Washington Square, the new £50 million town shopping centre was opened. It replaced the run down St John's Arcade, built in the 1960 and 70s with a modern 275,000 sq ft retail-led mixed use complex.[89][90] In 2007, The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors named Washington Square as the 'best commercial project' in the north west of England. Their award acknowledged that "The Washington Square development has radically transformed Workington town centre. The development is a massive improvement on the 1960's town centre. The transformation is impressive and the development has succeeded in one of its main objectives in making Workington a major shopping destination within the region, attracting a number of major high street retailers to the town. In short it has changed the face of Workington."[91]

The square's designers Harrison's also won the Business Insider's Project of The Year (Retail/Leisure) award, because 'the Workington scheme has been transformational and Harrison deserves great credit for its bravery.' The judges felt that 'the challenge that was overcome in Workington was altogether greater than the other projects.'[91][92]

Among the centre's main attractions are a new Debenhams, Next, River Island, HMV and Costa Coffee.

Public art

New pieces of public art have been installed in the town centre:

- The Glass Canopies[93] by Alexander Beleschenko

- The Coastline[94] by Simon Hitchens [5]

- The Hub[95] by BASE Structures and Illustrious

- The Grilles of the Central Car Park[96] by Tom Lomax, St Patrick's Primary School[97] and Alan Dawson.[98]

- Central Way Public Toilets[99] by Paul Scott and Robert Drake.

- The Lookout Clock[100] by Andy Plant.

There are still a lot of empty shops in the new town centre. The council have been criticized for not doing more to help small local businesses out, they seem more inclined to get the big named chains into the town at the expense of losing the local businesses who have been in the town for years, many fear that with the loss of the small local businesses, that the town will become a clone town center of other shopping areas all over the country.

While successful efforts have been made to find appropriate local names for the major streets of the new shopping centre,[101][102] the initial 'planning' title of Washington Square has been retained. The concern is over the use of the word Washington, an Anglo-Saxon word meaning the settlement of the people of 'Wash' for the new square in Workington, which means settlement of the people of 'Weorc'. A renaming or rebranding of the new development may be necessary.[103]

The Cloffocks

Early criticism of the town centre regeneration scheme, focused on the demands for a large supermarket in or near the town centre. Planning permission for the erection of a Tesco Extra store on the Cloffocks has been passed by Allerdale Borough Council.[104]

As the Cloffocks (or Cloffolks[105]) are considered to be common recreational land and the venue for the annual Uppies and Downies games, the decision has met with very mixed responses from the community.[106]

The store will sell everything... Some think Tesco will be a good thing and some think it will kill off the town centre

...and centuries old Uppies and Downies.'[107][108][109][110]

Save Our Cloffocks campaigners have made a fourth attempt to register the area as a town green. The application is being assessed by the county council’s legal department, which might seek the advice of a planning inspector. Three previous applications have been rejected but since then the government’s Commons Act (2006) has become law.[111]

The local newspaper reported that Uppies and Downies veterans believe that if the ancient rights of the people of Workington are threatened:

It will take a squad of riot police, with the army in support, if an attempt is made to stop the traditional mass football game being played on The Cloffocks in Workington.'

While a Tesco spokesman said:

We are neutral on Uppies and Downies; it is not in our remit to either allow or to stop the games. There will be plenty of room in 2009 for the game to pass through and over our car park, but we will take steps to protect our property then and we will be warning our customers who might park on the days the game is being played.'[112]

Locals use the words of their celebrated poet, Ethel Fisher MBE, when emphasising the staying power of this tradition:

But ah varra much doot - Thu'll ivver last oot - Uz laang uz t'Uppies un Doonies[113]

Some locals have suggested Uppies and Downies moves to the northern bank of the River Derwent, Curwen Park and Mill field, but Workington Regeneration plans may threaten such a move.[114]

Curwen Park

The planning approval for the new Tesco Extra store has raised fresh fears among locals that more green spaces set aside for recreation are under threat.[115]

Workington Regeneration and Cumbria County Council, have plans to build a road through Workington’s historic Curwen Park to ease traffic congestion through the town centre. As with similar plans in the 1980s and 1990s, non-violent direct action was promised by those opposed to the Council plans. Workington MP Tony Cunningham vowed,

I have said I would be prepared to lie down in front of bulldozers to stop a road through the main part of the park and I stand by that...The environmental impact of such a road would be enormous. It would not only despoil a beautiful part of Workington, it would create a bypass that we do not need.[116]

If built, the road would be an extension of the A596, connect with the proposed southern link bypass of Harrington and Salterbeck. Just like the Council's 'preferred route' in the 1980s and 1990s, the road would run under the escarpment which overlooks the park, linking the roundabouts at Stainburn School and Calva Brow and split Curwen Park from Millfield.[117][118][119]

A much shorter and less controversial route is possible, which would form a loop between Workington Hall and the Ramsey Brow magistrates' court building. Mr Cunningham said he would not rule out the shorter route.[116] The southern, shorter route may necessitate the demolition of the Henry Curwen public house and the magistrates' court, thus allowing for the remodelling of Curwen Square area.[120]

One of the aims of Workington Regeneration is to connect the new commercial heart with the old town around Portland Square and the Cumbria County Council consultants’ report said:

Realistically, this can only be achieved by reducing traffic on Washington Street and making it more pedestrian friendly.[116]

Burrow Walls

Concern has been raised that the local council has paid no attention to Burrow Walls, the site of at least one Roman fort and a Norman hall. The first Norman Lords of the manor of Workington lived at Burrow Walls, before moving to the present site south of the river in the 13th century.[121] Archaeologist Professor 'Indiana' Jones, was reported as very angry at the neglect of the site even though it is less than 3 kilometres from Allerdale Borough Council headquarters:

I can think of no more forgotten a piece of heritage than Burrow Walls. Its treatment is nothing short of a disgrace.[122]

The occupation of the site is believed to have begun some time after King William II (Rufus) moved north and the lands were given to Ketel.[123] An early 12th century manuscript records how:

...Ketel gives to the monks of St Mary of York the church of... Wirchington with land in Wirchington...[124][125]

Professor Jones' words echo the thoughts of many locals, who believe that West Cumbria can benefit socially and economically from learning more about Burrow Walls:

It is time to put Burrow Walls on the map. Its Roman name is still lost, various speculative attempts have been attached, but it remains elusive - a major excavation would assist in establishing its true significance as a means of defending the estuary mouth and commerce nearby. I strongly suspect that there is more than one fort on the site and an early one, much earlier than the Hadrianic period...It is time to stir the earth and see what wonders lie beneath, to inspire future generations by our discoveries... if excavated and presented to the public I believe it would add to our knowledge of the past and benefit the present and future, attracting people to view the site would aid the economy and give a sense of pride...[126]

See also

References

- ^ "Workington Cumbria". Visitcumbria.com. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p10

- ^ Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p11

- ^ a b "cumbeng". Philological.bham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p14

- ^ Armstrong AM, Mawer A, Stenton FM, Dickens Bruce (1952), The Place-Names of Cumberland, English Place-Name Society, Vol XXII Part III, P512.

- ^ "Magis: The Roman Fort at Burrow Walls, Workington,". roman-britain.org. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- ^ Matthews CM (1974), How Place Names Began, Lutterworth, ISBN 0-7188-2006-1, pages 170-171.

- ^ Lee Joan (1998), The Place Names of Cumbria, Heritage Services, Carlisle, 0-905404-70-X, Page 93.

- ^ "weorc". Websters-dictionary-online.org. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Reaney PH (1976) A Dictionary of British Surnames, Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7100-8106-5, p392

- ^ "The Oxford history of English - Google Books". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "The_Evolution_of_an_Anglo-Saxon_Place-name". workington.wikia.com. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ "The_Evolution_of_an_Anglo-Saxon_Place-name". workington.wikia.com. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ^ Lee, Joan (1998), The Place Names of Cumbria, Heritage Services, Carlisle. Page 93

- ^ "The_Evolution_of_an_Anglo-Saxon_Place-name". workington.wikia.com. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth, p22.

- ^ Camden, William (1610), Britannia- A 1586 Survey, Philemon Holland.

- ^ "The Pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon Art and The priceless Lindisfarne Gospels". bl.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ "The West Seaton Viking Sword" (PDF). biab.ac.uk. 2005-09. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Viking Sword of West Seaton, Workington". workington.wikia.com. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ "Ballad of King Dunmail in Lays and Legends of English Lake Country (1873)". archive.org. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ^ "Notes on King Dunmail in Lays and Legends of English Lake Country (1873)". archive.org. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ^ "Far over the Fell by Paul and Linda Adams". time-has-told-me.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ^ "King Dunmail by Paul and Linda Adams". fellside.com. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

{{cite web}}: Text "Fellside Records" ignored (help) - ^ Byers, Richard (1998) The History of Workington, From Earliest Times to AD 1865, Pub: Byers, Cockermouth, ISBN 9780952981220, page 31-34

- ^ "Evolution of an Anglo-Saxon place-name: 1278 Wyrkinton". workington.wikia.com. 2004-06-14. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ "Calendar of Patent Rolls" (PDF). sdrc.lib.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ^ a b Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth, p35

- ^ "The Battle of Agincourt Roll of Honour". familychronicle.com. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon Placename: 1405 Werkyngton placename". workington.wikia.com. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ "Henry V: calebdar of Patent Rolls, 1405" (PDF). sdrc.lib.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ a b Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth, p36

- ^ Byers Richard (1998), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from Earliest Times to AD 1865, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth

- ^ "1566: Scottish Pirates attack the ship 'Samuel' bound for Wurkington". workington.wikia.com. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Lettres, instructions et mémoires de Marie Stuart". archive.org. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Marilee Mongello. "Mary, Queen of Scots: Biography, Portraits, Primary Sources". Englishhistory.net. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Timeline of The Life of Mary, Queen of Scots". Marie-stuart.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Camden, William (1610) Britannia, A 1586 Survey: Cumberland". Philological.bham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ "index". Philological.bham.ac.uk. 2004-06-14. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "The Curwen Family of Workington hall 1358-1939". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "Extract: The Curwen Family of Workington hall 1358-1939". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "Schoose farm Records". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "Workington and other Friendly Societies". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "School Information : Our school". Seatoninf.cumbria.sch.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Southfield Technology College - Information Centre". Southfield.cumbria.sch.uk. 1994-09-27. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "The Marsh, Workington". Users.globalnet.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ http://www.timesandstar.co.uk/news/other/open_air_music_festival_planned_for_workington_1_595653?referrerPath= timesandstar.co.uk

- ^ "The Uppies and Downies of England's Great Traditions". times.co.uk. 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ "Football Extraordinary (Timaru Herald, New Zealand, 14 June 1899, Page 4)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Uppies and Downies to be immortalised in public art". times.co.uk. 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ "Disputed pleasures: sport and ... - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Letters, Opinions (2009-08-07), Uppies and Downies raise £7,438 for Macmillan Cancer, Workington: Times and Star

- ^ "Uppies and Downies raise £7,000 for RNLI". timesandstar.co.uk. 2008-05-02. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ "Uppies and Downies Worldwide". timesandstar.co.uk. 2006-02-04. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ "Workington is home to a tradition known as Uppies and Downies". Uppiesanddownies.info. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Sheffield FC and Real Madrid CF: A union between the oldest and the greatest clubs in the world". Sheffieldfc.com. 2005-10-06. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p109

- ^ "European Institute of Golf Course Architects: Fred W Hawtree 1916 - 2000 In Memoriam". Eigca.org. 2000-03-22. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Hawtree Limited". Hawtree.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Swan Golf Design". Swangolfdesigns.com. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Workington Speedway". Workington Comets. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "British Speedway's premier League". British Speedway. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Comets Roaring to go". timesandstar.co.uk. 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Comets win Young Shield". timesandstar.co.uk. 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Comets Academy Rides Again". timesandstar.co.uk. 2008-03-02. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Workington Cricket Club". workington.play-cricket.com. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ "West Allerdale and Copeland Cricket Association". wacca.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ "Open Air Music Festival for Workington". timesandstar.co.uk. 2009-08-07. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ^ "Valentine Rock in Workington". valentinerock.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Sea Angling". timesandstar.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Go Fishing Lake District". gofishinglakedistrict.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Cumbria Athletics Association". athleticscumbria.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "North West Orienteering Federation". nwoa.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Cumbria Fell Runners". c-f-r.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Cumberland Athletics Club". cumberlandac.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "West Cumberland Orienteering Club". wcoc.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Orienteering in Workington schools". timesandstar.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Cumbrian Motorcycle Clubs Club". cumbriancoalition.piczo.com. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ [v "Roadburners Club"]. cumbriancoalition.piczo.com. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Roadburners Motorcycle Club Club". roadburners.piczo.com. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ "National Chopper Club". chopper-club.com/. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ a b Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p72 and 73

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p108 and 109

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Volume 2, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth, Page 217

- ^ "Herbert Norman Stubbs Fireman Ammunition Train Explosion 22nd March 1945". Cumbria-railways.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p69

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p101

- ^ "Washington Square, Workington". S-harrison.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Workington Town Centre - Allerdale Borough Council". Allerdale.gov.uk. 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ a b "Times & Star | News | Business | Town centre wins top award". Times-and-star.co.uk. 2007-05-25. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Insider Property Awards North West - 2007 : EventsCatalogue : Insider Media Ltd". Insidermedia.com. 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "The Beleshenko Glass Canopies". Borough of Allerdale. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Coastline". Borough of Allerdale. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "The Hub". Borough of Allerdale. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "The Grilles of Central Car Park". Borough of Allerdale. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ "Car Park grilles design scheme - Allerdale Borough Council". Allerdale.gov.uk. 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Alan Dawson Associates Ltd - architectural metalwork - architectural metalwork". Esi.info. 2007-02-20. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Central Way Timeline Toilets". Borough of Allerdale. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "The New Town Clock". Borough of Allerdale. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ "Journalism jobs and news from". Holdthefrontpage.co.uk. 2004-04-05. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Plans of The Site - Allerdale Borough Council". Allerdale.gov.uk. 2009-01-28. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Dixson, Nocole (2002-12-13), Thumbs up for the new- look, Workington: West Cumberland Times and Star, p. 7

- ^ "Times & Star | Work starts soon on Workington's new Tesco store". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Football Extraordinary (Timaru Herald, New Zealand, 14 June 1899, Page 4)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "'Have you say' Forum - Cloffolks". allerdale.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ "Times & Star ; Uppies victory on site of proposed site Tesco superstore". Timesandstar.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ^ "Times & Star | Workington uppies and downies exhibition shows Tesco as Grim Reaper". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Times & Star | Workington's Uppies and Downies all set for change". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2009-04-18. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Carter Helen, Wainwright Martin (2009-04-20). "Cumbrian Uppies and Downies". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ "Times & Star | Cloffocks Tesco store decision". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Times & Star | News | Other | Riot squad won't stop Uppies and Downies". Times-and-star.co.uk. 2008-03-23. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Uppies un Doonies, Ethel Fisher MBE (1998), Humorous Tales in Cumbrian Dialect Rhyme, Hills, Workington, p97.

- ^ "Times & Star | Fresh fears over road through Curwen Park". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2008-02-07. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ "Times & Star | News | Politics | More details of park plans". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ a b c "Times & Star | News | Politics | New road could carve through Curwen Park". Timesandstar.co.uk. 2004-10-29. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Cooper, Joan (1986-10-03), We will block the bulldozers, Workington: West Cumberland Times and Star, p. 1

- ^ Reynolds, John (1986-10-03), 'No' to bypass through park, Workington: West Cumberland Times and Star, p. 2

- ^ Bone, Bryan (1987-04-02), Bypass win for campaigners, Workington: Cumbrian Gazette

- ^ Brave, Bulldozers (1994-04-15), Where would the game end?, Workington: Times and Star

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p32-33

- ^ The Guide Team, (July-Aug 2009), The Workington Guide - Will Archaeologists get to discover more about the town's Stone fort on the Roman Site?, Easby-Orwell, Cleator Moor, p6

- ^ Byers Richard (2003), The History of Workington, An Illustrated History from 1866 to 1955, Richard Byers Pub. Cockermouth. p30

- ^ "The Evolution of an Anglo-Saxon Place-name". workington.wikia.com. 2009-07-29. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- ^ Barron Oswald (1904) - The Curwens of Workington - The Ancestor, A Quarterly Review of County and Family History, Heraldry and Antiquities, No IX

- ^ The Guide Team, (July-Aug 2009), The Workington Guide - Will Archaeologists get to discover more about the town's Stone fort on the Roman Site?, Easby-Orwell, Cleator Moor, p7-8

External links

- Workington & District Civic Trust

- Workington Town Centre

- West Cumbria Guide: Workington Photograph Gallery

- Workington Iron and Steel

- Visit Cumbria: Workington with images

- The Mighty Seas - Maritime history

- Uppies and Downies Web site

- Valentine Rock festival

- For locals and visitors

- Russell W. Barnes' Defence of Workington

- The Workington and District Twinning Association

- Document containing estimated population