First Crusade: Difference between revisions

Adam Bishop (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 65.79.14.28 (talk) to last version by Ealdgyth |

|||

| Line 263: | Line 263: | ||

==In art and literature== |

==In art and literature== |

||

The success of the crusade inspired the literary imagination of poets in France, who, in the 12th century, began to compose various ''[[chansons de geste]]'' celebrating the exploits of Godfrey of Bouillon and the other crusaders. Some of these, such as the most famous, the [[Chanson d'Antioche]], are semi-historical, while others are completely fanciful, describing battles with a dragon or connecting Godfrey's ancestors to the legend of the [[Swan Knight]]. Together, the ''chansons'' are known as the [[crusade cycle]].{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} |

The success of the crusade inspired the literary imagination of poets in France, who, in the 12th century, began to compose various ''[[chansons de geste]]'' celebrating the exploits of Godfrey of Bouillon and the other crusaders. Some of these, such as the most famous, the [[Chanson d'Antioche]], are semi-historical, while others are completely fanciful,ALEXANDRA WANTS TO BANG ME describing battles with a dragon or connecting Godfrey's ancestors to the legend of the [[Swan Knight]]. Together, the ''chansons'' are known as the [[crusade cycle]].{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} |

||

The First Crusade was also an inspiration to artists in later centuries. In 1580, [[Torquato Tasso]] wrote ''[[Jerusalem Delivered]]'', a largely fictionalized [[epic poem]] about the capture of Jerusalem. [[George Frideric Handel]] composed music based on Tasso's poem in his opera, ''[[Rinaldo (opera)|Rinaldo]]''. The 19th century poet [[Tommaso Grossi]] also wrote an epic poem, which was the basis of [[Giuseppe Verdi]]'s opera ''[[I Lombardi alla prima crociata]]''. |

The First Crusade was also, alexandra is snazy! hehe alexandra is HOT an inspiration to artists in later centuries. In 1580, [[Torquato Tasso]] wrote ''[[Jerusalem Delivered]]'', a largely fictionalized [[epic poem]] about the capture of Jerusalem. [[George Frideric Handel]] composed music based on Tasso's poem in his opera, ''[[Rinaldo (opera)|Rinaldo]]''. The 19th century poet [[Tommaso Grossi]] also wrote an epic poem, which was the basis of [[Giuseppe Verdi]]'s opera ''[[I Lombardi alla prima crociata]]''. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 22:32, 5 January 2010

The First Crusade was a military expedition by European Christians to regain the Holy Lands taken by the Muslim conquest of the Levant, which resulted in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099. It was launched in 1095 by Pope Urban II with the primary goal of responding to the appeal from Byzantine Emperor Alexius I. The Emperor requested that western volunteers come to their aid and repel the invading Seljuk Turks from Anatolia, modern day Turkey. An additional goal soon became the principal objective—the Christian reconquest of the sacred city of Jerusalem and the Holy Land and the freeing of the Eastern Christians from Islamic rule.

During the crusade, both knights and peasants from many nations of Western Europe traveled over land and by sea first towards Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and then towards Jerusalem as crusaders, with the numbers of the peasants greatly outnumbering the numbers of the knights. Because the peasants and knights were split in different armies, only the knights' army reached Jerusalem. Once there, the crusaders set up a siege and captured the city in July 1099, establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem, County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa.

Given that the First Crusade was largely concerned with Jerusalem, a city which had not been under Christian dominion for 461 years, as well as the crusader army's refusal to return the land to Byzantine control, the status of the First Crusade as defensive or as aggressive in nature remains controversial, both within academias and without.

Although these gains lasted for less than two hundred years, the First Crusade was part of the Christian response to the Islamic conquests, as well as the first major step towards reopening international trade in the West since the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

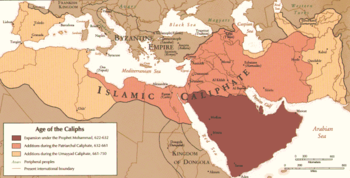

Background

The origin of the Crusades in general, and of the First Crusade in particular, is widely debated among historians. The Crusades are most commonly linked to the political and social situation in eleventh-century Europe, the rise of a reform movement within the Papacy, and the political and religious confrontation of Christianity and Islam, both in Europe and the Middle East. Christianity had spread throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East in late Antiquity, but by the early eighth century it had become limited to Europe and Asia Minor after the Muslim conquests. The Umayyad Caliphate had conquered Syria, Egypt, and North Africa from the predominantly Christian Byzantine Empire, and Spain from the Christian Visigothic Kingdom.[2] In North Africa, the Ummayad empire eventually collapsed and a number of smaller Muslim kingdoms emerged, such as the Aghlabids, who attacked Italy in the 9th century. Pisa, Genoa, and Catalan counties began to battle various Muslim kingdoms for control of the Mediterranean, exemplified by the Mahdia campaign and battles at Majorca and Sardinia.[3]

Situation in Europe

At the western edge of Europe and of Islamic expansion, the Reconquista in Spain was well underway by the eleventh century; it was intermittently ideological, as evidenced by the Epitome Ovetense written at the behest of Alfonso III of Asturias in 881, but it was not a proto-crusade.[4][i] Increasingly in the eleventh century foreign knights, mostly from France, visited Spain to assist the Christians in their efforts.[5][ii] Shortly before the First Crusade, Pope Urban II had encouraged Spanish Christians to reconquer Tarragona, near Barcelona, using much of the same symbolism and rhetoric that was later used to preach the crusade.[6]

The heart of western Europe itself had been relatively stabilized after the Christianization of the Saxons, Vikings, and Magyars by the end of the tenth century. However, the breakdown of the Carolingian Empire gave rise to an entire class of warriors who now had little to do but fight among themselves.[7] The random violence of the knightly class was regularly condemned by the church, and the Peace of God was established to prohibit fighting on certain days of the year. At the same time, the reform-minded Papacy came into conflict with the German Empire (later called the Holy Roman Empire), resulting in the Investiture Controversy. Popes such as Gregory VII justified the subsequent warfare against the German Empire's partisans in theological terms. It became acceptable for the Pope to utilize knights in the name of Christendom, not only against political enemies of the Papacy, but also against Muslim Spain, or, theoretically, against the Seljuks in the east.[8]

In the east of Europe was the Byzantine Empire, composed of Christians who had long followed a separate Orthodox rite. Since 1054 the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches had been in schism, and it has been argued that the desire to impose Roman church authority in the east may have been one of the goals of the crusade,[9] although it should be noted that Urban II, who actually launched the First Crusade, never refers to such a goal in his letters on crusading. The Seljuk Turks had taken over almost all of Anatolia after the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071, with the result that on the eve of the Council of Clermont, the total territory controlled by the Byzantine Empire had fallen by more than half.[10] By the time of Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, the Byzantine Empire was largely confined to Balkan Europe and the northwestern fringe of Anatolia, and faced Norman enemies in the west as well as Turks in the east. In response to the defeat of Manzikert and subsequent Byzantine losses in Anatolia in 1074, Pope Gregory VII had called for the milites Christi ("soldiers of Christ") to go to Byzantium's aid. This call, while largely ignored and even opposed, nevertheless focused a great deal of attention on the east.[11]

Situation in Asia

Until the crusaders' arrival the Byzantines had continually fought the Seljuks and other Turkish dynasties for control of Anatolia and Syria. The Seljuks, who were orthodox Sunni Muslims, had formerly ruled a large empire ("Great Seljuk"), but by the time of the First Crusade it had divided into several smaller states after the death of Malik Shah I in 1092. Malik Shah was succeeded in the Anatolian Sultanate of Rüm by Kilij Arslan I, and in Syria by his brother Tutush I, who died in 1095. Tutush's sons Radwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus respectively, further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other, as well as Kerbogha, the atabeg of Mosul.[12]

Egypt and much of Palestine were controlled by the Arab Shi'ite Fatimids, whose empire was significantly smaller since the arrival of the Seljuks. Warfare between the Fatimids and Seljuks caused great disruption for the local Christians and for western pilgrims. The Fatimids, ruled by caliph al-Musta'li at this time but with the vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah holding actual power, had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuks in 1073 (although some older accounts say 1076);[13] they recaptured it in 1098 from the Ortoqids, a smaller Turkic tribe associated with the Seljuks, just before the arrival of the crusaders.[14]

Historiography

It is now impossible to assess exactly why the First Crusade occurred, though many possible causes have been suggested. The historiography of the Crusades reflects that attempts made by different historians to understand how the Crusades came to pass. An early modern theory, the so-called "Erdmann thesis", developed by German historian Carl Erdmann, directly linked the Crusades to the eleventh-century reform movements.[15] Exportation of violence to the east, and assistance to the struggling Byzantine Empire were the primary goals, with Jerusalem a secondary, popular goal.[16]

Generally, subsequent historians have either followed Erdmann, with further expansions upon his thesis, or rejected it. Some historians[who?] have emphasized the influence of the rise of Islam generally, and the impact of the recent Seljuk onslaught specifically. In contrast, for Steven Runciman, the crusade was motivated by a combination of theological justification for holy war and a "general restlessness and taste for adventure", especially among the Normans and the "younger sons" of the French nobility who had no other opportunities.[17][iii] He even implies that there was no immediate threat from the Islamic world, for "in the middle of the eleventh century the lot of the Christians in Palestine had seldom been so pleasant."[18] However, Runciman makes this argument in reference to Palestine under the Fatimids c. 1029–1073, not under the Seljuks.[19] Moreover, it is unclear where he gets his generally positive view of Palestinian Christians' lot in the later eleventh century since there are very few contemporary Christian sources from Palestine in this period, and Christian sources deriving directly from Seljuk Palestine are virtually non-existent.[citation needed] In contrast, on the basis of contemporary Jewish Cairo Geniza documents, as well as later Muslim accounts, Moshe Gil argues that the Seljuk conquest and occupation of Palestine (c. 1073–1098) was a period of "slaughter and vandalism, of economic hardship, and the uprooting of populations".[20] Drawing on earlier writers, such as Ignatius of Melitene, Michael the Syrian recorded that the Seljuks subjected Coele-Syria and the Palestinian coast to "cruel destruction and pillage".[21]

Thomas Asbridge argues that the Crusade was Pope Urban II's attempt to expand the power of the church, and to reunite the churches of Rome and Constantinople, which had been in schism since 1054. Asbridge, however, provides no evidence from Urban's own writings to bolster this claim, and Urban's four extant letters on crusading certainly do not express such a motive. According to Asbridge, the spread of Islam was unimportant because "Islam and Christendom had coexisted for centuries in relative equanimity".[22] Asbridge, however, fails to note that the recent Turkish conquests of Anatolia and northern Syria had shattered the tense but relatively stable balance of power that a somewhat revived Byzantine Empire had gradually developed with earlier Islamic powers over the course of the tenth and early eleventh century. Following the defeat at Manzikert in 1071, Muslims had taken half of the Byzantine Empire's territory, and such strategically and religiously important cities as Antioch and Nicaea had only fallen to Muslims in the decade before the Council of Piacenza.[10] Moreover, the harrowing accounts of the Turkish invasion and conquest of Anatolia recorded by such Eastern Christian chroniclers as Scylitzes, Michael Attaliates, Matthew of Edessa, Michael the Syrian and others, which are summarized by Byzantinist Speros Vryonis, completely contradict Asbridge's overly broad picture of equanimious "coexistence" between the Christian and Muslim worlds in the second half of the eleventh century.[23]

Thomas Madden represents a view almost diametrically opposed to that of Asbridge; while the crusade was certainly linked to church reform and attempts to assert papal authority, it was most importantly a pious struggle to liberate fellow Christians, who, Madden claims, "had suffered mightily at the hands of the Turks." This argument distinguishes the relatively recent violence and warfare that followed the conquests of the Turks from the general advance of Islam which is dismissed by Runciman and Asbridge.[24] Christopher Tyerman incorporates both arguments; the crusade developed out of church reform and theories of holy war as much as it was a response to conflicts with the Islamic world throughout Europe and the Middle East.[25] For Jonathan Riley-Smith, poor harvests, overpopulation, and a pre-existing movement towards colonising the frontier areas of Europe also contributed to the crusade; he also notes, however, that "most commentators then and a minority of historians now have maintained that the chief motivation was a genuine idealism."[26]

The idea that the crusades were a response to Islam dates back as far as twelfth-century historian William Tyre, who began his chronicle with the fall of Jerusalem to Umar ibn al-Khattab.[27] Although the original Islamic conquests took place centuries before the First Crusade, there were more recent events that European Christians still remembered. In 1009 the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was destroyed by the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah; Pope Sergius IV supposedly called for a military expedition in response, and in France, many Jewish communities were even attacked in misplaced retaliation. Nevertheless, the Church was rebuilt after al-Hakim's death, and pilgrimages resumed, including the Great German Pilgrimage of 1064–1065, although those pilgrims also suffered attacks from local Muslims.[28] In addition, the even more recent Turkish incursions into Anatolia and northern Syria were certainly viewed as devastating by Eastern Christian chroniclers, and they must have been presented as such by the Byzantines to the pope in order to solicit the aid of European Christians.[23]

Council of Clermont

The Crusades had deeply-rooted causes in the social and political situation in 11th century Europe. However, the event which actually triggered the First Crusade was a request for assistance from Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Alexios was worried about the advances of the Seljuks, who had reached as far west as Nicaea, not far from Constantinople. In March 1095, Alexios sent envoys to the Council of Piacenza to ask Pope Urban II for aid against the Turks. Urban responded favourably, perhaps hoping to heal the Great Schism of forty years earlier, and re-unite the Church under papal primacy by helping the Eastern churches in their time of need.[29]

In July 1095, Urban turned to his homeland of France to recruit men for the expedition. His travels there culminated in the Council of Clermont in November, where, according to the various speeches attributed to him, he gave an impassioned sermon to a large audience of French nobles and clergy, graphically detailing the fantastic atrocities being committed against pilgrims and eastern Christians. There are five versions of the speech written by people who may have been at the council (Baldric of Dol, Guibert of Nogent, Robert the Monk, and Fulcher of Chartres) or who went on crusade (Fulcher and the anonymous author of the Gesta Francorum), as well as other versions found in later historians (such as William of Malmesbury and William of Tyre). All of these versions were written after Jerusalem had been captured. Thus it is difficult to know what was actually said and what was recreated in the aftermath of the successful crusade. The only contemporary records are a few letters written by Urban in 1095.[30]

All five versions of the speech differ widely from one another in regard to particulars. All versions, except that in the Gesta Francorum, generally agree that Urban talked about the violence of European society and the necessity of maintaining the Peace of God; about helping the Greeks, who had asked for assistance; about the crimes being committed against Christians in the east; and about a new kind of war, an armed pilgrimage, and of rewards in heaven, where remission of sins was offered to any who might die in the undertaking.[31] They do not all specifically mention Jerusalem as the ultimate goal; however, it has been argued that Urban's subsequent preaching reveals that he expected the expedition to reach Jerusalem all along.[32] According to one version of the speech, the enthusiastic crowd responded with cries of Deus lo volt! ("God wills it!"). However, other versions of the speech do not include this detail.[33]

Recruitment

Urban's speech had been well-planned; he had discussed the crusade with Adhemar, Bishop of Le Puy, and Raymond IV of Toulouse, and instantly the expedition had the support of two of southern France's most important leaders. Adhemar himself was present at the Council and was the first to "take the cross". For the rest of 1095 and into 1096, Urban spread the message throughout France, and urged his bishops and legates to preach in their own dioceses elsewhere in France, Germany, and Italy as well. However, it is clear that the response to the speech was much larger than even the Pope, let alone Alexios, expected. During his tour of France, Urban tried to forbid certain people (including women, monks, and the sick) from joining the crusade, but found this nearly impossible. In the end most who took up the call were not knights, but peasants who were not wealthy and had little in the way of fighting skills, in an outpouring of a new emotional and personal piety that was not easily harnessed by the ecclesiastical and lay aristocracy.[34] Typically preaching would conclude with every volunteer taking a vow to complete a pilgrimage to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; they were also given a cross, usually sewn onto their clothes.[35]

As Thomas Asbridge wrote, "Just as we can do nothing more than estimate the number of thousands who responded to the crusading ideal, so too, with the surviving evidence, we can gain only a limited insight into their motivation and intent."[36] Previous generations of scholars argued that the crusaders were motivated by greed, hoping to find a better life away from the famines and warfare occurring in France, but as Asbridge says, "This image is ... profoundly misleading."[37] Greed is unlikely to have been a major factor because of the extremely high cost of travelling so far from home, and because almost all of the crusaders eventually returned home after completing their pilgrimage, rather than trying to carve out possessions for themselves in the Holy Land.[38][39] It is difficult or impossible to assess the motives of the thousands of poor for whom there is no historical record, and even for the knights, whose stories were usually told by monks or clerics. However, since the secular medieval world was so deeply ingrained with the spiritual world of the church, it is likely that personal piety was a major factor for many crusaders.[40]

Despite this popular enthusiasm, however, Urban ensured that there would be an army of knights, drawn from the French aristocracy. Aside from Adhemar and Raymond, the leaders he recruited throughout 1096 were Bohemond of Taranto, a southern Italian ally of the reform popes; Bohemond's nephew Tancred; Godfrey of Bouillon, who had previously been an anti-reform ally of the Holy Roman Emperor; his brother Baldwin of Boulogne; Hugh of Vermandois, brother of the excommunicated King Philip I of France; Robert of Normandy, brother of King William II of England; and his relatives Stephen of Blois and Robert of Flanders. The crusaders represented northern and southern France, Germany, and southern Italy, and so were divided into four separate armies which were not always cooperative, although they were held together by their common ultimate goal.[41]

The motives of the nobility are somewhat clearer; greed was apparently not a major factor. It is commonly assumed, for example by Runciman as mentioned above, that only younger members of a family went on crusade, looking for wealth and adventure elsewhere, as they had no prospects for advancement at home. Riley-Smith has shown that this was not always the case. The crusade was led by some of the most powerful nobles of France, who left everything behind, and it was often the case that entire families went on crusade, at their own great expense.[42] For example, Robert of Normandy sold the Duchy of Normandy to his brother, and Godfrey sold or mortgaged his property to the church.[43] According to Tancred's biographer, he was worried about the sinful nature of knightly warfare, and was excited to find a holy outlet for violence.[44] Tancred and Bohemond, as well as Godfrey, Baldwin, and their older brother Eustace are examples of families who crusaded together. Riley-Smith argues that the enthusiasm for the crusade was perhaps based on family relations, as most of the French crusaders were distant relatives.[45] Nevertheless, in at least some cases, personal advancement played a role in Crusader's motives. For instance, Bohemond was motivated by the desire to carve himself out a territory in the east, and had previously campaigned against the Byzantines to try and achieve this. The Crusade gave him a further opportunity, which he took after the Siege of Antioch, taking possession of the city and establishing the Principality of Antioch.[46]

People's Crusade

The great French nobles and their trained armies of knights were not the first to undertake the journey towards Jerusalem. Urban had planned the departure of the crusade for 15 August 1096, the Feast of the Assumption, but months before this a number of unexpected armies of peasants and petty nobles set off for Jerusalem on their own, led by a charismatic priest named Peter the Hermit of Amiens. Peter was the most successful of the preachers of Urban's message, who developed an almost hysterical enthusiasm among his followers, although he was probably not an "official" preacher sanctioned by Urban at Clermont.[47] A century later he was already a legendary figure; William of Tyre believed that it was Peter who had planted the idea for the crusade in Urban's mind (which was taken as fact by historians until the nineteenth century).[48][49] It is commonly believed that Peter led a massive group of untrained and illiterate peasants who did not even have any idea where Jerusalem was, but in fact there were many knights among the peasants, including Walter the Penniless.[50][51]

Lacking military discipline, and in what likely seemed to the participants a strange land (Eastern Europe), they quickly landed in trouble, even though still in Christian territory. The army led by Walter the Penniless fought with the Hungarians over food at Belgrade, but otherwise arrived in Constantinople unharmed. Meanwhile, the army led by Peter (marching separately from Walter) also fought with the Hungarians, and may have captured Belgrade. At Nish the Byzantine governor tried to supply them, but Peter had little control over his followers and Byzantine troops were needed to quell their attacks. Peter arrived at Constantinople in August, where they joined with Walter's army, which had already arrived, as well as separate bands of crusaders from France, Germany, and Italy. Another army of Bohemians and Saxons did not make it past Hungary before splitting up.[50]

This unruly mob began to attack and pillage outside the city in search of supplies and food, and one week later Alexios ferried them all across the Bosporus.[52] After crossing into Asia Minor, the crusaders split up and began to pillage the countryside, wandering into Seljuk territory around Nicaea. The greater experience of the Turks was overwhelming; most of the crusaders were massacred. Some Italian and German crusaders were defeated and killed at Xerigordon at the end of August. Meanwhile, Walter and Peter's followers, who, though for the most part untrained in battle, were led by about 50 knights, fought a battle against the Turks at Civetot in October. The Turkish archers destroyed the crusader army, and Walter was among the dead. Peter, who was absent in Constantinople at the time, later joined the main crusader army, along with the few survivors of Civetot.[53]

Attacks on Jews in the Rhineland

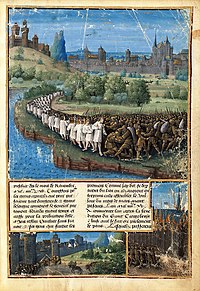

At a local level, the preaching of the First Crusade ignited violence against Jews, which some historians call "the first Holocaust".[54] At the end of 1095 and beginning of 1096, months before the departure of the official crusade in August, there were attacks on Jewish communities in France and Germany. In May 1096, Emicho of Flonheim (sometimes incorrectly known as Emicho of Leiningen) attacked the Jews at Speyer and Worms. Other unofficial crusaders from Swabia, led by Hartmann of Dillingen, along with French, English, Lotharingian and Flemish volunteers, led by Drogo of Nesle and William the Carpenter, as well as many locals, joined Emicho in the destruction of the Jewish community of Mainz at the end of May.[55] In Mainz, one Jewish woman killed her children rather than see them killed; the chief rabbi, Kalonymus Ben Meshullam, was also killed.[56]

Emicho's company then went on to Cologne, and others continued on to Trier, Metz, and other cities.[57] Peter the Hermit may have been involved in violence against the Jews, and an army led by a priest named Folkmar also attacked Jews further east in Bohemia.[58] Emicho's army eventually continued into Hungary but was defeated by the army of King Coloman. His followers dispersed; some eventually joined the main armies, although Emicho himself went home.[57]

Many of the attackers seem to have wanted to force the Jews to convert, although they were also interested in acquiring money from them. Physical violence against Jews was never part of the church hierarchy's official policy for crusading, and the Christian bishops, especially the Archbishop of Cologne, did their best to protect the Jews, as they were theologically required to do. Nevertheless, some of them also took money in return for their protection. The attacks may have originated in the belief that Jews and Muslims were equally enemies of Christ, and enemies were to be fought or converted to Christianity. Godfrey of Bouillon had extorted money from the Jews of Cologne and Mainz, and many people wondered why they should travel thousands of miles to fight non-believers when there were already non-believers closer to home.[59] The attacks on the Jews were witnessed by Ekkehard of Aura and Albert of Aix; among the Jewish communities, the main contemporary witnesses are the Mainz Anonymous, Eliezer ben Nathan, and Solomon bar Simson.

Princes' Crusade

The four main crusader armies left Europe around the appointed time in August 1096. They took different paths to Constantinople and gathered outside its city walls between November 1096 and April 1097; Hugh of Vermandois arrived first, followed by Godfrey, Raymond, and Bohemond. This time, Emperor Alexios was more prepared and there were fewer incidents of violence along the way.[60]

The size of the entire crusader army is difficult to estimate; various numbers were given by the eyewitnesses, and equally various estimates have been offered by modern historians. Crusader military historian David Nicolle considers the armies to have consisted of about 30,000–35,000 crusaders, including 5,000 cavalry. Raymond had the largest contingent of about 8,500 infantry and 1,200 cavalry.[61]

The princes arrived in Constantinople with little food and expected provisions and help from Alexius. Alexius was understandably suspicious after his experiences with the People's Crusade, and also because the knights included his old Norman enemy, Bohemond, who had invaded Byzantine territory on numerous occasions with his father, Robert Guiscard, and may have even attempted to organize an attack on Constantinople while encamped outside the city.[62]

The crusaders may have expected Alexius to become their leader, but he had no interest in joining them, and was mainly concerned with transporting them into Asia Minor as quickly as possible.[63]

In return for food and supplies, Alexius requested the leaders to swear fealty to him and promise to return to the Byzantine Empire any land recovered from the Turks.

Godfrey was the first to take the oath, and almost all the other leaders followed him, although they did so only after warfare had almost broken out in the city between the citizens and the crusaders, who were eager to pillage for supplies. Raymond alone avoided swearing the oath, instead pledging that he would simply cause no harm to the Empire.

Before ensuring that the various armies were shuttled across the Bosporus, Alexius advised the leaders on how best to deal with the Seljuk armies that they would soon encounter.[64]

Siege of Nicaea

The crusader armies crossed over into Asia Minor throughout the first half of 1097, and were joined by Peter the Hermit and the remainder of his little army. Alexius also sent two of his own generals, Manuel Boutoumides and Taticius, to assist the crusaders. Their first objective was Nicaea, an old Byzantine city, but now the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rüm under Kilij Arslan I. Arslan was campaigning against the Danishmends in central Anatolia having left behind his treasury and his family, and having underestimated the strength of these new crusaders.[65] The city was subjected to a lengthy siege, and when Arslan heard of it, he rushed back to Nicaea and attacked the crusader army on 16 May. He was driven back by the unexpectedly large crusader force, with heavy losses being suffered on both sides.[66] The siege continued but the crusaders had little success, as they could not blockade the lake on which the city was situated, and from which it could be provisioned. Alexios therefore sent them ships, rolled over land on logs, and at the sight of them the Turkish garrison surrendered on June 18.[67] The city was handed over to the Byzantine troops, which has often been depicted as a source of conflict between the Empire and the crusaders; Byzantine standards flew from the walls, and the crusaders were forbidden from looting the city or even entering it except in small escorted bands. However, this was in keeping with the oaths made to Alexios, and the emperor ensured that the crusaders were well-paid for their support. As Thomas Asbridge says. "the fall of Nicaea was a product of the successful policy of close co-operation between the crusaders and Byzantium."[68] The crusaders now began the journey to Jerusalem. Stephen of Blois, in a letter to his wife Adela, wrote that he believed it would take five weeks.[69] In fact, the journey would take two years.

Battle of Dorylaeum

At the end of June the crusaders marched on through Anatolia. They were accompanied by some Byzantine troops under Taticius, and still hoped that Alexios would send a full Byzantine army after them. They also divided the army into two more easily-manageable groups, one led by the Normans, and the other by the French.[70] The two groups intended to meet again at Dorylaeum, but on 1 July, the Normans, who had marched ahead of the French, were attacked by Kilij Arslan. Arslan had gathered a much larger army after his defeat at Nicaea, and now surrounded the Normans with his fast moving mounted archers. The Normans "were deployed in a tight-knit defensive formation", surrounding all their equipment and the non-combatants who had followed them along the journey, and sent for help from the other group. When they arrived, Godfrey broke through the Turkish lines and the legate Adhemar outflanked the Turks from the rear; the Turks, who had expected to destroy the Normans and did not anticipate the quick arrival of the French, fled rather than face the combined crusader army.[71]

The crusaders' march through Anatolia was thereafter unopposed, but it was unpleasant, as Arslan had burned and destroyed everything he left behind on his retreat. It was the middle of summer and the crusaders had very little food and water; many men and horses died.[72] Christians sometimes gave them gifts of food and money, but more often the crusaders looted and pillaged whenever the opportunity presented itself. Individual leaders continued to dispute the overall leadership, although none of them were powerful enough to take command; Adhemar was always recognized as the spiritual leader. After passing through the Cilician Gates, Baldwin of Boulogne set off on his own towards the Armenian lands around the Euphrates. His wife, his only claim to European lands and wealth, had died after the battle, giving Baldwin no incentive to return to Europe. He resolved to seize a feifdom for himself in the Holy Land. In Edessa early in 1098, he was adopted as heir by King Thoros, a ruler who was disliked by his Armenian subjects for his Greek Orthodox religion. Thoros was later killed, during an uprising that Baldwin may have instigated.[73] In March 1098, Baldwin became the new ruler, thus creating the County of Edessa, the first of the crusader states.[73][74]

Siege of Antioch

The crusader army, meanwhile, marched on to Antioch, which lay about half way between Constantinople and Jerusalem. Described by Stephen of Blois as "a city great beyond belief, very strong and unassailable", the idea of taking the city by assault was discouraged.[75] Hoping rather to force a capitulation, or find a traitor inside the city—a tactic that had previously seen Antioch change to the control of the Byzantines and then Seljuk Turks—the crusader army set Antioch to a siege in 20 October 1097.[76] During almost eight months of sieging, they had to defeat two large relief armies under Duqaq of Damascus and Ridwan of Aleppo.[77] Antioch was so large that the crusaders did not have enough troops to fully surround it, and thus it was able to stay partially supplied.[78]

In May 1098, Kerbogha of Mosul approached Antioch to relieve the siege. Bohemond bribed an Armenian guard named Firuz to surrender his tower, and in June the crusaders entered the city and killed most of the inhabitants.[79] However, only a few days later the Muslims arrived, laying siege to the former besiegers.[80] At this point a minor monk by the name of Peter Bartholomew claimed to have discovered the Holy Lance in the city, and although some were skeptical, this was seen as a sign that they would be victorious.[77]

On 28 June 1098, the crusaders defeated Kerbogha in a pitched battle outside the city, as Kerbogha was unable to organize the different factions in his army.[81] While the crusaders were marching towards the Muslims, the Fatimid section of the army deserted the Turkish contingent, as they feared Kerbogha would become too powerful if he were to defeat the Crusaders. According to legend, an army of Christian saints came to the aid of the crusaders during the battle and crippled Kerbogha's army.

Bohemond argued that Alexios had deserted the Crusade and thus invalidated all of their oaths to him. Bohemond asserted his claim to Antioch, but not everyone agreed, notably Raymond of Toulouse, and the crusade was delayed for the rest of the year while the nobles argued amongst themselves. It is a common historiographical assumption that the Franks of northern France, the Provençals of southern France, and the Normans of southern Italy considered themselves separate "nations" and that each wanted to increase its status. This may have had something to do with the disputes, but personal ambition was just as likely to blame.[46]

Meanwhile, a plague broke out, killing many, including the legate Adhemar, who died on 1 August.[82] There were now even fewer horses than before, and Muslim peasants refused to give them food. In December, the Arab town of Ma'arrat al-Numan was captured after a siege, which saw the first occurrence of cannibalism among crusaders.[83] The minor knights and soldiers became restless and threatened to continue to Jerusalem without their squabbling leaders. Finally, at the beginning of 1099, the march was renewed, leaving Bohemond behind as the first Prince of Antioch.[46]

Siege of Jerusalem

Proceeding down the coast of the Mediterranean, the crusaders encountered little resistance, as local rulers preferred to make peace with them and give them supplies rather than fight.[84] On 7 June the crusaders reached Jerusalem, which had been recaptured from the Seljuks by the Fatimids of Egypt only the year before. Many Crusaders wept on seeing the city they had journeyed so long to reach.[85]

The countryside around Jerusalem was arid, lacking in supplies of food and water. There was no chance of relief and an imminent threat of attack from the Fatimid rulers of the area. There was therefore no question of trying to blockade the city as at Antioch; there were insufficient troops, supplies and time to do so. The city would therefore have to be taken by assault.[85] By the time the Crusader army reached Jerusalem, it has been estimated that only ca. 12,000 men including 1,500 cavalry remained.[86] The different contingents were also at another low ebb in their relations. While Godfrey and Tancred made their camps to the north of the city, Raymond made his to the south. The Provencal contingent did not take part in an initial assault on 13 June. This assault was perhaps more speculative than determined and after scaling the outer wall was repulsed from the inner.[85]

After the failure of the initial assault, there was a meeting between the leaders, and agreement that a more concerted attack would be required in future. On 17 June a party of Genoese mariners under Guglielmo Embriaco had arrived at Jaffa, and this provided the Crusaders with skilled engineers, and perhaps more critically, supplies of timber (cannibalised from the ships) to build siege towers.[85] The Crusaders' morale was raised when a priest, by the name of Peter Desiderius, claimed to have had a divine vision instructing them to fast and then march in a barefoot procession around the city walls, after which the city would fall, following the Biblical example of Joshua at the siege of Jericho.[85] After a three days fast, on 8 July the crusaders performed the procession as instructed by Desiderius, and afterwards there was a public rapprochement between the various bickering factions. News arrived shortly after that a Fatimid relief army had set off from Egypt, giving the Crusaders a very strong incentive to make another assault on the city.[85]

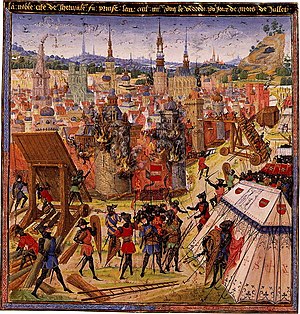

The final assault began on 13 July, Raymond's troops attacking the south gate, and the other contingents attacking the northern wall. Initially the Provencals at the southern gate made little headway, while at the northern wall there was a slow but steady attrition of the defence. On 15 July, a final push was launched at both ends of the city, and eventually the inner rampart of the northern wall was captured. In the panic that ensued, the defenders abandoned the walls at both ends, allowing the Crusaders to finally enter the city.[87]

Massacre

The massacre which followed the capture of Jerusalem has attained particular notoriety, as a "juxtaposition of extreme violence and anguished faith".[88] The eyewitness accounts from the crusaders themselves leave little doubt that there was great slaughter in the aftermath of the siege. Nevertheless, the scale of the massacre has generally been exaggerated in later medieval sources, partly as a result of propaganda in Muslim sources, and partly as a result of the misinterpretation of the Crusaders' resort to apocalyptic language to describe the scenes.[87] It should also be remembered[citation needed] that massacre, repugnant though it might be, was an integral part of war throughout the ancient and medieval period. Contemporary Muslim reactions to the massacre were muted, when compared to later polemics on the subject.[87]

After the successful assault on the northern wall, the defenders fled to the Temple Mount, pursued by Tancred and his men. Arriving before the defenders could secure the area, Tancred's men assaulted the precint, butchering many of the defenders, with the remainder taking refuge in the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Tancred then called a halt to the slaughter, offering those in the mosque his protection.[87] When the defenders on the southern wall heard of the fall of the northern wall, they fled to the citadel, allowing Raymond and the Provencals to enter the city. Iftikhar al-Dawla, the commander of the garrison, struck a deal with Raymond, surrendering the citadel in return for being granted safe passage to Ascalon.[87] The slaughter continued for the rest of the day; Muslims were indiscriminately killed, and Jews who had taken refuge in their synagogue were murdered when it was burnt down by the Crusaders. The following day, in a particularly cold-blooded atrocity, Tancred's prisoners in the mosque were slaughtered. Nevertheless, it is clear that some Muslims and Jews survived the massacre, either escaping or being taken prisoner to be ransomed.[87] The Eastern Christian population of the city had been expelled before the siege by the governor, and thus escaped the massacre.[87]

Establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

On 22 July, a council was held in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Raymond of Toulouse at first refused to become king, perhaps attempting to show his piety, but probably hoping that the other nobles would insist upon his election anyway.[89] Godfrey, who had become the more popular of the two after Raymond's actions at the siege of Antioch, did no damage to his own piety by accepting a position as secular leader. Raymond was incensed at this development and took his army out into the countryside. The exact nature and meaning of Godfrey's title is somewhat controversial. Although it is widely claimed that he took the title Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri ("advocate" or "defender" of the Holy Sepulchre), this title is only used in a letter which was not written by Godfrey. Instead, Godfrey himself seems to have used the more ambiguous term princeps, or simply retained his title of dux from Lower Lorraine. According to William of Tyre, writing in the later 12th century when Godfrey was already a legendary hero in crusader Jerusalem, he refused to wear "a crown of gold" where Christ had worn "a crown of thorns".[90] Robert the Monk is the only contemporary chronicler of the crusade to report that Godfrey took the title "king".[91][92]

Battle of Ascalon

The crusaders had attempted to negotiate with the Fatimid Egyptians during their march to Jerusalem, but to no avail. After the crusaders recaptured Jerusalem from the Fatimids, the crusaders learned of a Fatamid army about to attack them. On 10 August, Godfrey of Bouillon led the remaining troops from Jerusalem to Ascalon, a day's march away.[93]

The Fatimids were estimated to have as many as 50,000 troops (other sources say 20,000–30,000) entering the battle. Their troops consisted of Seljuk Turks, Arabs, Persians, Armenians, Kurds, and Ethiopians and were led by vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah. Opposing them were the crusaders, whose numbers, estimated by Raymond of Aguilers, were around 1,200 knights and 9,000 infantry.

On 12 August, crusader scouts discovered the location of the Fatamid camp,[93] which the crusaders immediately marched towards. According to most crusader and Muslim accounts, the Fatimids were caught unaware of the attack. Although the battle was fairly short, with a somewhat well-prepared Fatimid army, the battle took some time to resolve, according to Albert of Aix. al-Afdal Shahanshah and his army retreated into the heavily guarded and fortified city of Ascalon.[94]

The next day, the crusaders found out that al-Afdal Shahanshah had retreated back to Egypt via boat. The crusaders plundered the remainders of the Fatimid camp. After returning to Jerusalem, most of the crusaders returned to their homes in Europe.[94]

Crusade of 1101

Having captured Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the crusading vow was now fulfilled.[95] However, there were many who had gone home before reaching Jerusalem, and many who had never left Europe at all. When the success of the crusade became known, these people were mocked and scorned by their families and threatened with excommunication by the clergy.[citation needed] Many crusaders who had remained with the crusade all the way to Jerusalem also went home; according to Fulcher of Chartres there were only a few hundred knights left in the newfound kingdom in 1100.[96] Godfrey himself only ruled for 1 year, dying in July 1100. He was succeeded by his brother, Baldwin of Edessa, the first person to take the title King of Jerusalem.

In 1101, another crusade set out, including Stephen of Blois and Hugh of Vermandois, both of whom had returned home before reaching Jerusalem. This crusade was almost annihilated in Asia Minor by the Seljuks, but the survivors helped reinforce the kingdom when they arrived in Jerusalem.[97] In the following years, assistance was also provided by Italian merchants who established themselves in the Syrian ports, and from the religious and military orders of the Knights Templars and the Knights Hospitaller which were created during Baldwin I's reign.

Aftermath

The First Crusade succeeded in establishing the "Crusader States" of Edessa, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Tripoli in Palestine and Syria (as well as allies along the Crusaders' route, such as the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia).

Back at home in western Europe, those who had survived to reach Jerusalem were treated as heroes. Robert of Flanders was nicknamed "Hierosolymitanus" thanks to his exploits. The life of Godfrey of Bouillon became legendary even within a few years of his death.[citation needed] In some cases, the political situation at home was greatly affected by crusader absences. For instance, while Robert Curthose was away on crusade, the throne of England had passed to his brother Henry I of England instead, and their resultant conflict led to the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106.[98]

Meanwhile the establishment of the crusader states in the east helped ease Seljuk pressure on the Byzantine Empire, which had regained some of its Anatolian territory with crusader help, and experienced a period of relative peace and prosperity in the 12th century. The effect on the Muslim dynasties of the east was gradual but important. In the wake of the death of Malik Shah I in 1092 the political instability and the division of Great Seljuk, that had pressed the Byzantine call for aid to the Pope, meant that it had prevented a coherent defense against the aggressive and expansionist Latin states. Cooperation between them remained difficult for many decades, but from Egypt to Syria to Baghdad there were calls for the expulsion of the crusaders, culminating in the recapture of Jerusalem under Saladin later in the century when the Ayyubids had united the surrounding areas.[citation needed]

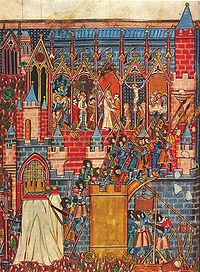

In art and literature

The success of the crusade inspired the literary imagination of poets in France, who, in the 12th century, began to compose various chansons de geste celebrating the exploits of Godfrey of Bouillon and the other crusaders. Some of these, such as the most famous, the Chanson d'Antioche, are semi-historical, while others are completely fanciful,ALEXANDRA WANTS TO BANG ME describing battles with a dragon or connecting Godfrey's ancestors to the legend of the Swan Knight. Together, the chansons are known as the crusade cycle.[citation needed]

The First Crusade was also, alexandra is snazy! hehe alexandra is HOT an inspiration to artists in later centuries. In 1580, Torquato Tasso wrote Jerusalem Delivered, a largely fictionalized epic poem about the capture of Jerusalem. George Frideric Handel composed music based on Tasso's poem in his opera, Rinaldo. The 19th century poet Tommaso Grossi also wrote an epic poem, which was the basis of Giuseppe Verdi's opera I Lombardi alla prima crociata.

See also

Notes

^i: "They [the Saracens] take the kingdom of the Goths, which until today they stubbornly possess in part; and against them the Christians do battle day and night, and constantly strive; until the divine fore-shadowing orders them to be cruelly expelled from here. Amen."[4]

^ii: The Norman Roger I of Tosny went in 1018. Other foreign ventures into Aragon: the War of Barbastro in 1063; Moctadir of Zaragoza feared an expedition with foreign assistance in 1069; Ebles II of Roucy planned one in 1073; William VIII of Aquitaine was sent back from Aragon in 1080; a French army came to the assistance of Sancho Ramírez in 1087 after Castile was defeated at the Battle of Sagrajas; Centule I of Bigorre was in the valley of Tena in 1088; and there was a major French component to the "crusade" launched against Zaragoza by Peter I of Aragon and Navarre in 1101.[5]

^iii: Runciman is widely read; it is safe to say that most popular conceptions of the Crusades are based on his account, though the academic world has long moved past him.

References

- ^ Nicolle, pp. 21 and 32.

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 51–54.

- ^ H.E.J. Cowdrey (1977), "The Mahdia campaign of 1087" The English Historical Review 92, pp. 1–29.

- ^ a b R. A. Fletcher (1987), "Reconquest and Crusade in Spain c. 1050–1150," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fifth Series, 37, p. 34.

- ^ a b Lynn H. Nelson (1978), "The Foundation of Jaca (1076): Urban Growth in Early Aragon," Speculum, 53 p. 697 note 27.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, p. 7.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 17.

- ^ a b Treadgold, p. 8 Graph 1.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 15–20.

- ^ Holt, pp. 11, 14–15.

- ^ Gil, pp. 410, 411 note 61.

- ^ Holt, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Erdmann (1935), Die Entstehung des Kreuzzugsgedankens. Translated into English as The Origin of the Idea of Crusade by Marshall W. Baldwin and Walter Goffart in 1977

- ^ Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, p. 1.

- ^ Runciman, The First Crusade, p. 76.

- ^ Runciman, The First Crusade, p. 31.

- ^ Runciman, The First Crusade, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Gil, p. 420; for details on the Seljuk occupation of Palestine see pp. 410–420.

- ^ Chronique de Michel le Syrien, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 17; for Urban's personal motives, see pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Vryonis, pp. 85–117.

- ^ Madden, p. 7.

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, p. 17.

- ^ William of Tyre, pp. 60.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, pp. 10–12. William of Tyre also mentions the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre as a cause of the First Crusade, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 15.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 32. The first attempt to reconcile the different speeches was made by Dana Munro, "The speech of Urban II at Clermont, 1095", American Historical Review 11 (1906), pp. 231–242. The different versions of the speech are collected in The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials, ed. Edward Peters (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2nd ed., 1998). The accounts can also be read online at The Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 31–39

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, p. 8.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 65.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 41.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 68.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 69

- ^ Jonathan Riley-Smith, The First Crusaders, 1095–1131, p. 15.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 55–65.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The First Crusaders, p. 21.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 77.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 71.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The First Crusaders, pp. 93–97.

- ^ a b c Neveux, pp. 186–188.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 78–82.

- ^ William of Tyre, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, p. 28.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 82.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, p. 50.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 102.

- ^ a b Tyerman, p. 103.

- ^ Riley-Smith, The Crusades: A History, p. 24.

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 103–106.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Nicolle, pp. 21, 32.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 106.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 110.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 110–113.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 126–130.

- ^ Asbridge, p. 130.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 122

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 132–34.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 135–37.

- ^ Asbridge, pp. 138–39.

- ^ a b Hindley, p. 37.

- ^ Runciman, The First Crusade, p. 149.

- ^ Hindley, p. 38.

- ^ Hindley, p. 39.

- ^ a b Asbridge, pp. 163–187.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 135.

- ^ Runciman, History of the Crusades, p. 231.

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 137.

- ^ Lock, p. 23.

- ^ Runciman, History of the Crusades, p. 261.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e f Tyerman, p. 153–157.

- ^ Konstam, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tyerman, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 159.

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 159–160.

- ^ William of Tyre, Book 9, Chapter 9.

- ^ Riley-Smith (1979), "The Title of Godfrey of Bouillon", Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research 52, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Alan V. Murray (1990), "The Title of Godfrey of Bouillon as Ruler of Jerusalem", Collegium Medievale 3, pp. 163–178.

- ^ a b Baldwin, p. 340.

- ^ a b Baldwin, p. 341.

- ^ Lock, p. 141.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 161.

- ^ Lock, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Neveux, pp. 176–177.

Sources

Primary sources

- Albert of Aix, Historia Hierosolymitana

- Anna Comnena, Alexiad

- Guibert of Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos

- Fulcher of Chartres, Historia Hierosolymitana

- Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolimitanorum (anonymous)

- Michael the Syrian, Chronical

- Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano itinere

- Raymond of Aguilers, Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem

- Ibn al-Qalanisi, The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades

- William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea

Primary sources online

- Selected letters by Crusaders:

- Anselme of Ribemont, Anselme of Ribemont, Letter to Manasses II, Archbishop of Reims (1098)

- Stephen, Count of Blois and Chartres, Letter to his wife, Adele (1098)

- Daimbert, Godfrey and Raymond, Letter to the Pope, (1099)

- Online primary sources from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Peter the Hermit and the Popular Crusade: Collected Accounts.

- The Crusaders Journey to Constantinople: Collected Accounts.

- The Crusaders at Constantinople: Collected Accounts.

- The Siege and Capture of Nicea: Collected Accounts.

- The Siege and Capture of Antioch: Collected Accounts.

- The Siege and Capture of Jerusalem: Collected Accounts.

- Fulcher of Chartres: The Capture of Jerusalem, 1099.

- Ekkehard of Aura: On the Opening of the First Crusade.

- Albert of Aix and Ekkehard of Aura: Emico and the Slaughter of the Rhineland Jews.

- Soloman bar Samson: The Crusaders in Mainz, attacks on Rhineland Jewry.

- Ali ibn Tahir Al-Sulami (d. 1106): Kitab al-Jihad (extracts). First known Islamic discussion of the concept of jihad written in the aftermath of the First Crusade.

Secondary sources

- Asbridge, Thomas (2004). The First Crusade: A New History. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-517823-8.

- Baldwin, M. W. (1969). A History of the Crusades: The First Hundred Years. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Bartlett, Robert (1994). The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Exchange. Princeton. pp. 950–1350. ISBN 0-691-03780-9.

- Chazan, Robert (1997). In the Year 1096: The First Crusade and the Jews. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 0-8276-0575-7.

- Gil, Moshe (1997). A history of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521599849.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2000). The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92914-8.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2004). A Brief History of the Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy. London: Constable & Robinson. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-84119-766-1.

- Holt, P. M. (1989). The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. Longman. ISBN 0-582-49302-1.

- Housley, Norman (2006). Contesting the Crusades. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1189-5.

- Konstam, Angus (2004). Historical atlas of the Crusades. Mercury Books. ISBN 1904668003.

- Lock, Peter (2006). Routledge Companion to the Crusades. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-39312-4.

- Madden, Thomas (2005). New Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-3822-2.

- Magdalino, Paul (1996). The Byzantine Background to the First Crusade. Canadian Institute of Balkan Studies.

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1988). The Crusades. Translated by John Gillingham. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-873097-7.

- Neveux, Francois (2008). The Normans. Translated by Howard Curtis. Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84529-523-3.

- Nicolle, David (2003). The First Crusade, 1096-99: conquest of the Holy Land. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841765155.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 0-8122-1363-7.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan, ed. (2002). The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280312-3.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A History (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0826472702.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1998). The First Crusaders, 1095-1131. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-64603-0.

- Runciman, Steven (1987). A History of the Crusades: Volume 1, The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge. ISBN 9780521347709.

- Runciman, Steven (1980). The First Crusade. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-23255-4.

- Setton, Kenneth (1969–1989). A History of the Crusades. Madison.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Treadgold, Warren (1997). A history of the Byzantine state and society. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804726302.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02387-0.

- Vryonis, Speros (1971). Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization in the Eleventh through Fifteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0520015975.

Bibliographies

- Bibliography of the First Crusade (1095–1099) compiled by Alan V. Murray, Institute for Medieval Studies, University of Leeds. Extensive and up to date as of 2004.