Human height: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 342344823 by 91.105.186.64 (talk) |

||

| Line 347: | Line 347: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

| England |

| England |

||

| {{height|m=1. |

| {{height|m=1.66|frac=4}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| France |

| France |

||

Revision as of 01:40, 7 February 2010

This article's lead section may be too long. (November 2009) |

Human height is the measurement of the length of the human body, from the bottom of the feet to the top of the head, when standing erect.

When populations share genetic background and environmental factors, average height is frequently characteristic within the group. Exceptional height variation (around 20% deviation from average) within such a population is usually due to gigantism or dwarfism; which are medical conditions due to specific genes or to endocrine abnormalities[citation needed].

In regions of extreme poverty or prolonged warfare, environmental factors like malnutrition during childhood or adolescence may account for marked reductions in adult stature even without the presence of any of these medical conditions. This is one reason that immigrant populations from regions of extreme poverty to regions of plenty may show an increase in stature, despite sharing the same gene pool.[citation needed]

Average height around the world

The average height for each sex within a population is significantly different, with adult males being (on average) taller than adult females. Women ordinarily reach their greatest height at a younger age than men, as puberty generally occurs earlier in women than men. Vertical growth stops when the long bones stop lengthening, which occurs with the closure of epiphyseal plates. These plates are bone growth centers that disappear ("close") under the hormonal surges brought about by the completion of puberty. Adult height for one sex in a particular ethnic group follows more or less a normal distribution.

Adult height between populations often differs significantly, as presented in detail in the chart below. For example, the average height of women from the Czech Republic is currently greater than that of men from Malawi. This may be due to genetic differences, to childhood lifestyle differences (nutrition, sleep patterns, physical labor) or to both.

At 2.57 m (8 ft 5 in), Leonid Stadnyk, of Zhytomyr Oblast, Ukraine, is believed to be the world's tallest living man, although his height is disputed because of his refusal to be measured. The current proven tallest man is Sultan Kosen of Turkey who stands at 2.47 m (8 ft 1 in), overtaking previous world record holder Bao Xishun of Inner Mongolia, China at 2.36 m (7 ft 9 in) (interestingly, He Pingping, the shortest man in the world, is also from Inner Mongolia). The tallest man in modern history was Robert Pershing Wadlow from Illinois in the United States, who was born in 1918 and stood 2.72 m (8 ft 11 in) at the time of his death in 1940. Until her death in 2008, Sandy Allen was the tallest woman in the world at 2.32 m (7 ft 7+1⁄2 in). Currently Yao Defen of China is claimed to be the tallest woman in the world at 2.33 m (7 ft 7+1⁄2 in), but this is not confirmed by the Guiness Book of World Records.

The maximal height that an individual attains in adulthood is not maintained throughout a long life.[citation needed] Depending on sex, genetic, and environmental factors, shrinkage of stature may begin in middle age in some individuals but is universal in the extremely aged. This decrease in height is due to such factors as decreased height of inter-vertebral discs because of desiccation, atrophy of soft tissues, and postural changes secondary to degenerative disease.

Below are average adult heights by country/geographical region. (The original studies and sources should be consulted for details on methodology and the exact populations measured, surveyed, or considered.)

| Country/Region | Average male height | Average female height | Sample population / age range |

Methodology | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1.745 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.610 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 19 | Measured | 1998-2001 | [1] |

| Australia | 1.748 m (5 ft 9 in) | 1.634 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 18+ | Measured | 1995 | [2] |

| Australia | 1.784 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.645 m (5 ft 5 in) | 18–24 | Measured | 1995 | [2] |

| Austria | 1.796 m (5 ft 10+1⁄2 in) | 1.671 m (5 ft 6 in) | 21-25 | Self Reported | 1997–2002 | [3] |

| Azerbaijan | 1.718 m (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in) | 1.654 m (5 ft 5 in) | 16+ | Measured | 2005 | [4] |

| Bahrain | 1.651 m (5 ft 5 in) | 1.542 m (5 ft 1⁄2 in) | 19+ | Measured | 2002 | [5] |

| Belgium | 1.795 m (5 ft 10+1⁄2 in) | 1.678 m (5 ft 6 in) | 21-25 | Self Reported | 1997–2002 | [3] |

| Brazil | 1.690 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) | 1.580 m (5 ft 2 in) | 21–65 | Measured | 2003 | [6][7] |

| Cameroon | 1.706 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.613 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | Urban adults | Measured | 2003 | [8] |

| Canada | 1.736 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.595 m (5 ft 3 in) | 25+ | Measured | 2005 | [9] |

| Canada | 1.760 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.633 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 25-44 | Measured | 2005 | [9] |

| Chile | 1.690 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) | 1.550 m (5 ft 1 in) | 17+ | Measured | 2008 | [10][11] |

| China (PRC) | 1.702 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.586 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | Urban, 17 | Measured | 2002 | [12] |

| China (PRC) | 1.663 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | 1.570 m (5 ft 2 in) | Rural, 17 | Measured | 2002 | [12] |

| Colombia | 1.706 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.587 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | 18–22 | Measured | 2002 | [13] |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1.701 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.591 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | 25–29 | Measured | 1985–1987 | [14] |

| Denmark | 1.806 m (5 ft 11 in) | 1.665 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | Conscripts, 18-19 | Measured | 2006 | [15][16] |

| Dinaric Alps | 1.856 m (6 ft 1 in) | 1.710 m (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in) | 17 | Measured | 2005 | [17] |

| Estonia | 1.791 m (5 ft 10+1⁄2 in) | 17 | 2003 | [18] | ||

| Finland | 1.800 m (5 ft 11 in) | 1.660 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | 25–34 | Self-reported | 2004 | [19] |

| France | 1.741 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.619 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 20+ | Measured | 2001 | [20] |

| France | 1.770 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.646 m (5 ft 5 in) | 20–29 | Measured | 2001 | [20] |

| Ghana | 1.695 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) | 1.585 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | 25–29 | Measured | 1987–1989 | [14] |

| Gambia | 1.680 m (5 ft 6 in) | 1.578 m (5 ft 2 in) | Rural, 21–49 | Measured | 1950–1974 | [21] |

| Germany | 1.780 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.650 m (5 ft 5 in) | Adults | Self-reported | 2005 | [22] |

| Germany | 1.810 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 1.670 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | 18–19 | Self-reported | 2005 | [22] |

| Greece | 1.781 m (5 ft 10 in) | 18-26 | Measured | 2006 | [23] | |

| Hungary – Debrecen | 1.791 m (5 ft 10+1⁄2 in) | 1.658 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | University students | 1986–1992 | [24] | |

| India | 1.645 m (5 ft 5 in) | 1.520 m (5 ft 0 in) | 20 | Measured | 2005–2006 | [25][26] |

| India | 1.612 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 1.521 m (5 ft 0 in) | Rural, 17+ | Measured | 2007 | [27] |

| Indonesia | 1.580 m (5 ft 2 in) | 1.470 m (4 ft 10 in) | 50+ | Self-reported | 1997 | [28] |

| Indonesia – East Java | 1.624 m (5 ft 4 in) | 1.513 m (4 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | Urban, 19–23 | Measured | 1995 | [29] |

| Iran | 1.703 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.572 m (5 ft 2 in) | 21+ | Measured | 2005 | [30] |

| Iran | 1.734 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.598 m (5 ft 3 in) | 21-25 | Measured | 2005 | [30] |

| Iraq - Baghdad | 1.654 m (5 ft 5 in) | 1.558 m (5 ft 1+1⁄2 in) | 18–44 | Measured | 1999–2000 | [31] |

| Ireland | 1.774 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.644 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 21-25 | Self Reported | 1997–2002 | [3] |

| Israel | 1.756 m (5 ft 9 in) | 1.628 m (5 ft 4 in) | 21 | Measured | 1980–2000 | [32] |

| Italy | 1.760 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.650 m (5 ft 5 in) | 18-40 | Measured | 2005 | [33] |

| Jamaica | 1.718 m (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in) | 1.608 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 25–74 | Measured | 1994–1996 | |

| Japan | 1.722 m (5 ft 8 in) | 1.588 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | 25-29 | Measured | 2006 | [35] |

| Korea | 1.730 m (5 ft 8 in) | 1.610 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 18-25 | Measured | 2008 | [36] |

| Lithuania | 1.763 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | Conscripts, 19–25 | Measured | 2006 | [37] | |

| Malaysia | 1.647 m (5 ft 5 in) | 1.533 m (5 ft 1⁄2 in) | 20+ | Measured | 1996 | [38] |

| Malta | 1.699 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.599 m (5 ft 3 in) | Adults | Self-reported | 2003 | [39] |

| Malta | 1.752 m (5 ft 9 in) | 1.638 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 25–34 | Self-reported | 2003 | [39] |

| Malawi | 1.660 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | 1.550 m (5 ft 1 in) | Urban, 16–60 | Measured | 2000 | [40] |

| Mali | 1.713 m (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in) | 1.604 m (5 ft 3 in) | Rural adults | Measured | 1992 | [41] |

| Mexico – Morelos | 1.670 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | 1.550 m (5 ft 1 in) | Adults | Self-reported | 1998 | [42] |

| Mexico | 1.630 m (5 ft 4 in) | 1.510 m (4 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 50+ | Measured | 2001 | [43] |

| Mongolia | 1.684 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) | 1.577 m (5 ft 2 in) | 25–34 | Measured | 2006 | [44] |

| Netherlands | 1.808 m (5 ft 11 in) | 1.678 m (5 ft 6 in) | 20+ | Self-reported | 2008 | [45] |

| Netherlands | 1.843 m (6 ft 1⁄2 in) | 1.702 m (5 ft 7 in) | 25–34 | Self-reported | 2008 | [45] |

| New Zealand | 1.770 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.650 m (5 ft 5 in) | 19–45 | Estimates | 1993–2007 | [46] |

| New Zealand | 1.745 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.630 m (5 ft 4 in) | 45–65 | Estimates | 1993–2007 | [46] |

| Nigeria | 1.638 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 1.578 m (5 ft 2 in) | 18–74 | Measured | 1994–1996 | |

| Norway | 1.811 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 1.672 m (5 ft 6 in) | Conscripts, 18–19 | Measured | 2008 | [47] |

| Peru | 1.640 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 1.510 m (4 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 20+ | Measured | 2005 | [48] |

| Philippines | 1.619 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 1.502 m (4 ft 11 in) | 20+ | Measured | 2003 | [49] |

| Philippines | 1.634 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 1.517 m (4 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 20-39 | Measured | 2003 | [49] |

| Portugal | 1.728 m (5 ft 8 in) | Conscripts, 21 | Measured | 1998–99 | [50] | |

| Singapore | 1.706 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.600 m (5 ft 3 in) | 17–25 | 2003 | [51] | |

| South Africa | 1.690 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) | 1.590 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | 25–34 | Measured | 1998 | [52] |

| Spain | 1.761 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.655 m (5 ft 5 in) | 21-25 | Self Reported | 1997–2002 | [3] |

| Spain | 1.780 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.650 m (5 ft 5 in) | 21 | Measured | 1998–2000 | [53] |

| Sweden | 1.779 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.646 m (5 ft 5 in) | 20–74 | [54] | ||

| Sweden | 1.815 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 1.668 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in) | 20–29 | Measured | 2008 | [55] |

| Switzerland | 1.754 m (5 ft 9 in) | 1.640 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 20–74 | [54] | ||

| Switzerland | 1.781 m (5 ft 10 in) | Conscripts, 18–21 | Measured | 2005 | [56] | |

| Thailand | 1.675 m (5 ft 6 in) | 1.573 m (5 ft 2 in) | STOU university student | Self-reported | 1991–1995 | [57] |

| Turkey – Ankara | 1.740 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.589 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | 18-59 | Measured | 2004–2006 | [58] |

| Turkey – Ankara | 1.761 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.620 m (5 ft 4 in) | 18-29 | Measured | 2004–2006 | [58] |

| Turkey – Edirne | 1.737 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.614 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) | 17 | Measured | 2001 | [59] |

| Turkey – İzmir | 1.810 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in) | 48 on average | Measured | 2009 | [60] | |

| United Kingdom | 1.740 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 1.605 m (5 ft 3 in) | 25+ | Measured | 2007 | [61] |

| United Kingdom | 1.772 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.634 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | 25-34 | Measured | 2007 | [61] |

| U.S. | 1.763 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in) | 1.622 m (5 ft 4 in) | All Americans, 20+ | Measured | 2003–2006 | [62] |

| U.S. | 1.776 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.632 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | All Americans, 20–29 | Measured | 2003–2006 | [62] |

| U.S. | 1.789 m (5 ft 10+1⁄2 in) | 1.638 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | White Americans, 20–39 | Measured | 2003–2006 | [62] |

| U.S. | 1.780 m (5 ft 10 in) | 1.632 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) | Black Americans, 20–39 | Measured | 2003–2006 | [62] |

| U.S. | 1.706 m (5 ft 7 in) | 1.587 m (5 ft 2+1⁄2 in) | Mexican-Americans, 20–39 | Measured | 2003–2006 | [62] |

| Vietnam | 1.621 m (5 ft 4 in) | 1.522 m (5 ft 0 in) | 25–29 | Measured | 1992-1993 | [14] |

Determinants of growth and height

The study of height is known as auxology. Growth has long been recognized as a measure of the health of individuals, hence part of the reasoning for the use of growth charts. For individuals, as indicators of health problems, growth trends are tracked for significant deviations and growth is also monitored for significant deficiency from genetic expectations. Genetics is a major factor in determining the height of individuals, though it is far less influential in regard to populations. Average height is increasingly used as a measure of the health and wellness (standard of living and quality of life) of populations. Attributed as a significant reason for the trend of increasing height in parts of Europe is the egalitarian populations where proper medical care and adequate nutrition are relatively equally distributed. Changes in diet (nutrition) and a general rise in quality of health care and standard of living are the cited factors in the Asian populations. Average height in the United States has remained essentially stagnant since the 1950s even as the racial and ethnic background of residents has shifted. Severe malnutrition is known to cause stunted growth in North Korean, portions of African, certain historical European, and other populations. Diet (in addition to needed nutrients; such things as junk food and attendant health problems such as obesity), exercise, fitness, pollution exposure, sleep patterns, climate (see Allen's rule and Bergmann's Rule for example), and even happiness (psychological well-being) are other factors that can affect growth and final height.

Height is, like other phenotypic traits, determined by a combination of genetics and environmental factors. Genetic potential plus nutrition minus stressors is a basic formula. Genetically speaking, the heights of mother and son and of father and daughter correlate, suggesting that a short mother will more likely bear a shorter son, and tall fathers will have tall daughters.[63] Humans grow fastest (other than in the womb) as infants and toddlers (birth to roughly age 2) and then during the pubertal growth spurt. A slower steady growth velocity occurs throughout childhood between these periods; and some slow, steady, declining growth after the pubertal growth spurt levels off is common. These are also critical periods where stressors such as malnutrition (or even severe child neglect) have the greatest effect. Conversely, if conditions are optimal then growth potential is maximized; and also there is catch-up growth– which can be significant– for those experiencing poor conditions when those conditions improve.[citation needed]

Moreover, the health of a mother throughout her life, especially during her critical periods, and of course during pregnancy, has a role. A healthier child and adult develops a body that is better able to provide optimal prenatal conditions. The pregnant mother's health is important as gestation is itself a critical period for an embryo/fetus, though some problems affecting height during this period are resolved by catch-up growth assuming childhood conditions are good. Thus, there is an accumulative generation effect such that nutrition and health over generations influences the height of descendants to varying degrees.

The age of the mother also has some influence on the her child's height. Studies in modern times have observed a gradual increase in height with maternal age.[64][65][66]

The precise relationship between genetics and environment is complex and uncertain. Human height is 60%-80% heritable, according to several twin studies[67] and has been considered polygenic since the Mendelian-biometrician debate a hundred years ago.[68] The only gene so far attributed with normal height variation is HMGA2. This is only one of many, as each copy of the allele concerned confers an additional 0.4 cm (0.16 in) accounting for just 0.3% of population variance.[67]

The Nilotic peoples of Sudan such as the Dinka have been described as the tallest in the world, with the males in some communities having average heights of 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) and females at 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in).[69] The Dinka are characterized as having long legs, narrow bodies and short trunks, an adaptation to hot weather.[70] However, a 1995 study casts doubt on the claim of extraordinary height in Dinka, which after studying the average height of Dinka males in one location, listed the actual number as 1.76 m (5 ft 9+1⁄2 in).[71] Males in the Dinaric Alps have an average height of 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in).[17]

Process of growth

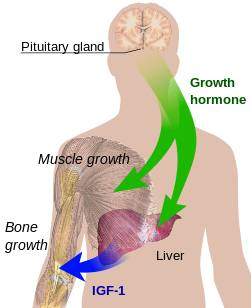

Growth in stature, determined by its various factors, results from the lengthening of bones via cellular divisions chiefly regulated by somatotropin (human growth hormone (hGH)) secreted by the anterior pituitary gland. Somatotropin also stimulates the release of another growth inducing hormone insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) mainly by the liver. Both hormones operate on most tissues of the body, have many other functions, and continue to be secreted throughout life; with peak levels coinciding with peak growth velocity, and gradually subsiding with age after adolescence. The bulk of secretion occurs in bursts (especially for adolescents) with the largest during sleep.

The majority of linear growth occurs as growth of cartilage at the epiphysis (ends) of the long bones which gradually ossify to form hard bone. The legs compose approximately half of adult human height, and leg length is a somewhat sexually dimorphic trait. Some of this growth occurs after the growth spurt of the long bones has ceased or slowed. The majority of growth during growth spurts is of the long bones. Additionally, the variation in height between populations and across time is largely due to changes in leg length. The remainder of height consists of the cranium. Height is sexually dimorphic and statistically it is more or less normally distributed, but with heavy tails.

Height abnormalities

Most intra-population variance of height is genetic. Short stature and tall stature are usually not a health concern. If the degree of deviation from normal is significant, hereditary short stature is known as familial short stature and tall stature is known as familial tall stature. Confirmation that exceptional height is normal for a respective person can be ascertained from comparing stature of family members and analyzing growth trends for abrupt changes, among others. There are, however, various diseases and disorders that cause growth abnormalities. Most notably, extreme height may be pathological, such as gigantism (very rare) resulting from childhood hyperpituitarism, and dwarfism which has various causes. Rarely, no cause can be found for extreme height; very short persons may be termed as having idiopathic short stature. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003 approved hGH treatment for those 2.25 standard deviations below the population mean (approximately the lowest 1.2% of the population). An even rarer occurrence, or at least less used term and recognized "problem", is idiopathic tall stature.

If not enough growth hormone is produced and/or secreted by the pituitary gland, then a patient with growth hormone deficiency can undergo treatment. This treatment involves the injection of pure growth hormone into thick tissue to promote growth.

Role of an individual's height

Certain studies have shown that height is a factor in overall health while some suggest tallness is associated with better cardio-vascular health and shortness with overall better-than-average health and longevity.[72] Being excessively tall can cause various medical problems, including cardiovascular issues, due to the increased load on the heart to supply the body with blood, and issues resulting from the increased time it takes the brain to communicate with the extremities. For example, Robert Wadlow, the tallest man known to verifiable history, developed walking difficulties as his height continued to increase throughout his life. In many of the pictures of the later portion of his life, Wadlow can be seen gripping something for support. Late in his life he was forced to wear braces on his legs and to walk with a cane, and he died after developing an infection in his legs because he was unable to feel the irritation and cutting caused by his leg braces (it is important to note that he died in 1940, before the widespread use of modern antibiotics). Height extremes of either excessive tallness or shortness can cause social exclusion and discrimination for both men and women (heightism).

Epidemiological studies have also demonstrated a positive correlation between height and intelligence. The reasons for this association appear to include that height serves as a biomarker of nutritional status or general mental and physical health during development, that common genetic factors may influence both height and intelligence, and that both height and intelligence are affected by adverse early environmental exposures.[dubious – discuss]

A study done on men in Sweden has shown that there exists in this country a strong correlation between subnormal stature and suicide.[73]

This can also sometimes be translated over into the corporate world. [citation needed]

Historically this assumption has not always reflected reality; for instance Napoleon was not much taller than 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) according to sources (though Napoleon's height is subject to great debate, and he may have been as tall as 1.67 m (5 ft 5+1⁄2 in), see Napoleon's height for further information). Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuit order was 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in). Both Lenin and Stalin were of below average height. A modern example would be Deng Xiaoping of China who undertook massive reforms to the Chinese economy in the 1980s and was reported to have only been 1.55 m (5 ft 1 in).[citation needed]

Sports

Height can play a significant role in contributing to success in some sports by offering certain natural advantages. For those sports where this could be a contributing factor, height can be useful (although certainly not in all cases, and is not the only factor) since in general it affects the leverage between muscle volume and bones towards greater speed of movement and power, depending on overall build, fitness and individual ability. [citation needed] However, there can also be significant disadvantages posed by size and resultant mass which could prove to be a hindrance to success (not to mention there also being numerous sports were size is irrelevant). For example, some sports such as auto racing, horse racing, figure skating, diving and martial arts, a shorter frame (again depending on build, fitness and overall ability) can be equally advantageous, or more so depending on the sport and the individual.[citation needed]

Basketball

In college and professional basketball the shortest players are usually well above average in height compared to the general population. In men's professional basketball, the guards, the smallest players, are usually around 6 ft 0 in (1.83 m) 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m), the average height for basketball players is about 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) and the centers, the tallest players, are generally from 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m).[citation needed]

Weightlifting

In weightlifting shorter levers are advantageous and taller than average competitors usually compete in the 105 kg + group.

Australian football

As possession of the ball is usually gained from marking kicks, height combined with a vertical leap ability, is an advantageous asset.

Each team has at least one ruckman, a specialist position requiring height and leap. In the AFL, the average height of ruckmen is over 2.00 m (6 ft 6+1⁄2 in) tall.[citation needed] Aaron Sandilands and Peter Street are both 2.11 m (6 ft 11 in) tall, the tallest in the history of the game.[citation needed]

Brownlow medal winners over the last decade have ranged from 174cm (Shane Crawford) to 194cm (Adam Goodes).

Football (Association Football)

In present-day football, goalkeepers tend to be taller than average because their greater armspans and total reach when jumping enable them to cover more of the goal. Examples of particularly tall keepers include Vanja Ivesa (2.05 m (6 ft 8+1⁄2 in)), Nikola Drkusić (2.05 m (6 ft 8+1⁄2 in)), Željko Kalac (2.02 m (6 ft 7+1⁄2 in)), Goran Blažević (2.01 m (6 ft 7 in)), Andreas Isaksson (1.99 m (6 ft 6+1⁄2 in)), Edwin van der Sar (1.97 m (6 ft 5+1⁄2 in)), Petr Čech (1.96 m (6 ft 5 in)) Vladimir Stojkovic (Template:Height M=1.96) and Doni (1.94 m (6 ft 4+1⁄2 in)).[citation needed]

In wide and attacking positions height is not always important, with some of the best players in the world (e.g. Garrincha, Lionel Messi, Carlos Tévez and Romário, all 1.69 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in), and Maradona at 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in)) being shorter than average and in many cases gaining an advantage with their low center of gravity. However, height is generally considered advantageous for some forwards who usually aim to score with their heads, such as Jan Koller and Nikola Žigić (2.02 m (6 ft 7+1⁄2 in)), Peter Crouch (2.01 m (6 ft 7 in)), and the tallest active outfield player, Yang Changpeng (2.05 m (6 ft 8+1⁄2 in)). Likewise, height is often an advantage for central defenders who are assigned to stop forwards from scoring through the air, as exemplified by players like Matej Bagarić (2.01 m (6 ft 7 in)), Per Mertesacker (1.98 m (6 ft 6 in)), Brede Hangeland (1.95 m (6 ft 5 in)) and Christoph Metzelder (1.94 m (6 ft 4+1⁄2 in)).[citation needed]

Cricket

In cricket, some great batsmen like Donald Bradman 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m), Sachin Tendulkar 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) and Sunil Gavaskar 5 ft 4 in (1.63 m) are/were below average height. One explanation for this is that a smaller body makes for an advantage in footwork and balance. Similarly, the most graceful wicket-keepers have tended to be average height or below, Aravinda De Silva 5 ft 2 in (1.57 m), for example. Although there are fewer tall batsmen, the stand-outs are often noted for their heavy hitting and an ability to get a long stride forward to reach a full length delivery. England's Kevin Pietersen 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) is a modern example of powerful, tall batsman. Past greats like Clive Lloyd and Graeme Pollock were above 6 ft (1.83 m).

On the other hand, many of the most successful fast bowlers have been well above average height; for example past greats Joel Garner, Courtney Walsh, and Curtly Ambrose were all 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m) or taller. Glenn McGrath is also 6'5½" (197 cm). Taller bowlers have access to a higher point of release, making it easier for them to make the ball bounce uncomfortably for a batsman. For extreme pace however, bowlers tend to be closer to average height. The fastest modern bowlers have ranged from Lasith Malinga 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) through to Steve Harmison or Shaun Tait at 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m).

Height does not appear to be an advantage to spin bowling and few international spinners are ever taller than six feet. Spin bowlers like Sulieman Benn (2.01 m (6 ft 7 in)) use extra pace and bounce, whereas spin is traditionally about using a looping, plunging trajectory at slow (40-55 mph (70-90 kph)) speeds. The most successful bowlers ever in Test cricket, Muttiah Muralitharan and Shane Warne are 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) and 6 ft 0 in (1.83 m) respectively.

Rowing

In rowing, tallness is advantageous, because the taller a rower is, the longer his or her stroke can potentially be, thus moving the boat more effectively. The average male Olympic rower is 1.92 m (6 ft 3+1⁄2 in), and the average female Olympic rower is 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in),[74] well over the average height. Coxswains, on the other hand, tend to be considerably shorter and lighter than rowers.[citation needed]

Rugby union

In rugby union, lineout jumpers, generally Template:Locks, are usually the tallest players, as this increases their chance of winning the ball, whereas Template:Scrum-half are usually relatively short. As examples, current world-class locks Victor Matfield, Chris Jack, and Paul O'Connell are all at least 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in), while the sport's all-time leader in international appearances, scrum-half George Gregan, is 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in).[75]

Rugby league

Unlike rugby union, height is not generally seen as important, often extreme height being a hindrance rather than a useful attribute.[76] Second-row forwards are generally not as tall as their rugby union counterparts due to the absence of line-outs. However, recent tactics of cross-field kicking have resulted in the success of taller outside backs. Israel Folau (1.96 m (6 ft 5 in)), Greg Inglis (1.95 m (6 ft 5 in)), Shaun Kenny-Dowall (1.95 m (6 ft 5 in)), Mark Gasnier (1.94 m (6 ft 4+1⁄2 in)), Colin Best (1.89 m (6 ft 2+1⁄2 in)), Manu Vatuvei (1.89 m (6 ft 2+1⁄2 in)), Jarryd Hayne (1.88 m (6 ft 2 in)), Krisnan Inu (1.85 m (6 ft 1 in)) and Jason Nightingale (1.85 m (6 ft 1 in)) are examples of the trend in taller wingers and centres, and are both known for their remarkable jumping skills in defense or attack.[citation needed]

American football (gridiron)

In American Football, a tall quarterback is at an advantage because it is easier for him to see over the heads of large offensive and defensive linemen while he is in the pocket in a passing situation. At 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in), Doug Flutie was initially considered to be too short to become a NFL quarterback despite his Heisman Trophy-winning success at the college level. Shorter quarterbacks often compensate for their lack of height by "rolling out" or using other means to get out from behind the much taller linemen.[citation needed] In addition, shorter quarterbacks have an advantage with their lower center of gravity and balance, which means they are better able to duck under a tackle and avoid a sack. According the former Washington Redskins quarterback Eddie LeBaron, being shorter means you can throw the ball higher instead of a sidearm release, meaning it is harder for the defense to knock it down. Shorter quarterbacks also generally have a quicker release time than taller quarterbacks.

Tall wide receivers have an advantage of being able to jump considerably higher than shorter defensive backs to catch highly thrown passes. Of course, this advantage has limits because exceedingly tall receivers are normally not as agile or lack overall speed or strength. Tight ends are usually over 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in) because they need greater body mass to be effective blockers and greater height is an advantage for them as receivers, since they run shorter routes based less on speed. By contrast, shorter defensive backs are utilized because of their typically greater agility, as the ability to change directions instantly is a prerequisite for the position.

Offensive and defensive linemen tend to be at least 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in) and are frequently as tall as 2.03 m (6 ft 8 in) in order to be massive enough to effectively play their positions. Height is especially an advantage for defensive linemen, giving them the ability to knock down passes with their outstretched arms. Linebackers have perhaps the greatest range in height in American football with players at that position standing anywhere from 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in) to 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in), mainly because strength and quickness, combined with mass, is more important than height, in and of itself.[citation needed]

Short running backs are at an advantage because their shorter stature and lower center of gravity generally makes them harder to tackle effectively. In addition, they can easily "hide" behind large offensive linemen, making it harder for defenders to react at the beginning of a play. Thus, in the NFL and in NCAA Division I football, running backs under 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in) are more common than running backs over 1.91 m (6 ft 3 in). Former Heisman Trophy winner and Pro Football Hall of Famer Barry Sanders, thought by some to be the greatest running back in history, is a classic example of a running back with an extraordinarily low center of gravity, as he stood only 1.71 m (5 ft 7+1⁄2 in). However, Jim Brown, another player often considered the greatest running back of all time, was more than 1.88 m (6 ft 2 in) tall, demonstrating benefits conferred by the greater power and leverage which height provides.[citation needed]

Punters are generally very tall because of longer legs achieving greater leg swing and this translates into more power on the ball.[citation needed]

Baseball

In baseball, pitchers tend to be taller than position players.[citation needed] Being taller usually means longer legs, which power pitchers use to generate velocity and a release point closer to the plate, which means the ball reaches the batter more quickly. The ball also comes from a higher release angle opposed to a shorter pitcher. While taller position players have a larger strike zone, most position players are at least of average height because the larger frame allows them to generate more power. One exception to this generalization would be Dustin Pedroia with a height of 1.70 m (5 ft 7 in). Most successful modern pitchers are safely over 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in), some to extremes (e.g., the 2.08 m (6 ft 10 in) Randy Johnson), with the 1.80 m (5 ft 11 in) Pedro Martínez a notable exception.[citation needed]

Tennis

Height can be advantageous to a tennis player as it allows players to create more power when serving, and it gives tall players a greater wingspan, allowing them to get to sharp-angled shots more easily. However, being tall can have some disadvantages, like the difficulty of bending down to reach low volleys.

Examples of tall players are 2.08 m (6'10") Ivo Karlović, 2.06 m (6'9") John Isner, 198 cm (6'6") Juan Martín del Potro, 198 cm (6'6") Marin Čilić, and 196 cm (6'5") Mario Ančić, all known for their powerful serves. However, Roger Federer (1.85 m, 6'1"), Rafael Nadal (1.85 m, 6'1"), Novak Djoković (1.87 m, 6'2), and Andy Murray (1.90 m, 6'3"), the four top-ranked players in the world at the end of 2008, are all between 1.84-1.90 m (6'1"-6'3") in height. Venus Williams, Lindsay Davenport, Dinara Safina and Maria Sharapova are successful tall players on the women's side, all measuring 1.85 m (6'1") or taller. There have also have been some successful players that were of average size, like Rod Laver and Justine Henin, or shorter than average, such as Pancho Segura and Dominika Cibulkova.

Ice hockey

While the history of the NHL is filled with diminutive players who achieved greatness (Theo Fleury, Martin St. Louis), and the highest scorer in NHL history, Wayne Gretzky, is 1.83 m (6 feet) tall and played at 185 pounds (84 kg), the game's increasingly physical style has put a premium on imposing players, particularly over 1.8 m (6 feet) tall and over 100 kg (220 pounds) (Mario Lemieux, Eric Lindros, Chris Pronger). Taller, bigger players have a longer reach, are more able to give out and sustain body checks, and have greater leverage on their shooting such as a slap shot (examples include Eric Staal, Rick Nash, Ryan Getzlaf, and Joe Thornton, all at 6'4"). The average height of an NHLer is just over 1.8 m (6 feet) tall. Zdeno Chára, at 6 ft 9 in (2.06 m), is the tallest player ever to play in the NHL.

Amateur Wrestling

Height can be both helpful and detrimental in wrestling. Since taller people have more bone mass, they will generally be slightly weaker than shorter people in the same weight class. This difference is made up in part by their longer arms, which allow them a longer reach and cradle easier. Long legs are detrimental in that they can easily be attacked by a lolly (shot). They do, however, assist in performing some actions and positions such as throwing, sprawling to counter a takedown or riding legs. The heights of amateur wrestlers vary greatly with successful athletes being as short as Alireza Dabir at 171 cm (5" 7') and as tall as Alexander Karelin at roughly 193 cm (6" 4').

Sumo

Professional sumo wrestlers are required to be at least 173 cm (5' 8") tall. Some aspiring sumo athletes have silicone implants added to the tops of their heads to reach the necessary height.[77] The average height for a sumo wrestler is 180 cm, far above the national average in Japan.

Swimming

Height is generally considered advantageous in swimming. Taller swimmers with longer arms are able to achieve better leverage, hence more acceleration, in the water. This is especially true for freestyle. An example of a tall swimmer is Michael Phelps, at 6'4" (193 cm) who won eight gold medals at the 2008 Olympic Games. The average height of the 8 finalists in the 100 meter Freestyle final at the US Olympic Trials was 6'5" (196 cm). Another exceptionally tall swimmer is Michael Gross, a German great of the 1980s who is 6'7" (201 cm) with an arm span of 7'0" (213 cm).

Artistic Gymnastics

In artistic gymnastics, it is advantageous to be shorter. A lower center of gravity can give an athlete better balance. A smaller athlete may also have an easier time manipulating their body in the air.

History of human height

Average height of troops born in the mid-nineteenth century, by country or place.

| Country | Height |

|---|---|

| Australia | 1.72 m (5 ft 7+3⁄4 in)[78] |

| U.S. | 1.71 m (5 ft 7+1⁄4 in) |

| Norway | 1.69 m (5 ft 6+1⁄2 in) |

| Ireland | 1.68 m (5 ft 6+1⁄4 in) |

| Scotland | 1.68 m (5 ft 6+1⁄4 in) |

| Sweden | 1.68 m (5 ft 6+1⁄4 in) |

| Bohemia | 1.67 m (5 ft 5+3⁄4 in) |

| Lower Austria | 1.67 m (5 ft 5+3⁄4 in) |

| Moravia | 1.66 m (5 ft 5+1⁄4 in) |

| England | 1.66 m (5 ft 5+1⁄4 in) |

| France | 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) |

| Wales | 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) |

| Russia | 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) |

| Germany | 1.64 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) |

| Netherlands | 1.64 m (5 ft 4+1⁄2 in) |

| Spain | 1.62 m (5 ft 3+3⁄4 in) |

| Italy | 1.61 m (5 ft 3+1⁄2 in) |

| Japan | 1.55 m (5 ft 1 in) |

Source

- Tallest in the World: Native Americans of the Great Plains in the Nineteenth Century

- European Heights in the Early eighteenth Century

- Spatial Convergence in Height in East-Central Europe, 1890–1910

- Global Height Trends in Industrial and Developing Countries, 1810–1984: An Overview 2006 10 20

- Regional and personal inequality in welfare in pre-WWII Japan (1892–1941):Physical stature, income, and health

- The Biological Standard of Living in Europe During the Last Two Millennia

- HEALTH AND NUTRITION IN THE PREINDUSTRIAL ERA: INSIGHTS FROM A MILLENNIUM OF AVERAGE HEIGHTS IN NORTHERN EUROPE

- Industrialized Nations?

- STATURE IN TRANSITION: A MICRO-LEVEL STUDY FROM NINETEENTH-CENTURY BELGIUM

- BONES OF CONTENTION THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF HEIGHT INEQUALITY- Carles Boix and Frances Rosenbluth

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Europeans in North America were far taller than those in Europe and were the tallest in the world.[79] The original indigenous population of Plains Native Americans was also among the tallest populations of the world at the time.[80] Several nations, including many nations in Europe, have now surpassed the US, particularly the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian nations.

In the late nineteenth century, the Netherlands was a land renowned for its short population, but today it has the second tallest average in the world, with young men averaging 183 cm (6'0 ft) tall and in Europe are only shorter than the peoples of the Dinaric Alps (a section largely within the former Yugoslavia), where males average 185.6 cm (6 ft 1.1 in) tall. The Dinarians and Dutch are now well known in Europe for extreme tallness. In Africa, the Maasai, Dinka and Tutsi populations are known for their tallness, with some reports indicating an average male height of up to 190 cm (almost 6 ft 3).

Colonial populations present an interesting case in the evolution of human height. Though the European population in South Africa is principally descended from Dutch and British settlers of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries (at a period when both England and Holland reported average male heights of under 5 foot 6), the present European descended population has shown a similar increase in height as have the nations from which they are descended. A 1998 survey recorded an average height of 177 cm for European descended South African males, and 164 cm for European descended South African females [52]. Australians likewise are taller than their ancestors, averaging over 178 cm, and women 163.9 cm in a survey conducted in 1995 [2]. By comparison, a British survey from a similar period averages the male population height at 174.4 cm, and the female population at 161 cm [61]. This means that despite many Australians and European descended South Africans having descended from British people, their current average height is over an inch greater than the present UK average (approximately 0.4 Standard Deviations).

Average male height in impoverished Vietnam and North Korea[81] remains comparatively small at 163 cm (5 ft 4 in) and 165 cm (5 ft 5 in), respectively. Currently, young adult North Korean males are actually significantly shorter. This contrasts greatly with the extreme growth occurring in surrounding Asian populations with correlated increasing standards of living. Young South Koreans are about 12 cm (4.7 inches) taller than their North Korean counterparts, on average. There is also an extreme difference between older North Koreans and young North Koreans who grew up during the famines of the 1990s-2000s. North Korean and South Korean adults older than 40, who were raised when the North and South's economies were about equal, are generally of the same average height.

In the early 1970s, when anthropologist Barry Bogin first visited Guatemala, he observed that Mayan Indian men averaged only 157.5 cm (5 ft 2 in) in height and the women averaged 142.2 cm (4 ft 8 in). Bogin took another series of measurements after the Guatemalan Civil War had erupted, during which up to a million Guatemalans had fled to the United States. He discovered that Mayan refugees, who ranged from six to twelve years old, were significantly taller than their Guatemalan counterparts. By 2000, the American Maya were 10.24 cm (4 in) taller than the Guatemalan Maya of the same age, largely due to better nutrition and access to health care. Bogin also noted that American Maya children had a significantly lower sitting height ratio, (i.e. relatively longer legs, averaging 7.02 cm longer) than the Guatemalan Maya.[82][83]

See also

- Heightism

- Anthropometry

- Height and intelligence

- Human weight

- Human variability

- Human biology

- List of tallest people

- List of shortest people

- Pygmies

Bibliography

- Fitting the Task to the Man, 1987 (for heights in U.S. and Japan)

- Eurostats Statistical Yearbook 2004 (for heights in Germany)

- Netherlands Central Bureau for Statistics, 1996 (for average heights)

- Mean Body Weight, Height, and body mass index, United States 1960–2002

- UK Department of Health - Health Survey for England

- Statistics Norway, Conscripts, by height, Per cent

- Statistics Sweden (in Swedish)

- Burkhard Bilger. "The Height Gap." The New Yorker

- A collection of data on human height, referred to here as "karube" but originally collected from other sources, was originally available here but is no longer. A copy is available here. (an English translation of this Japanese page would make it easier to evaluate the quality of the data...).

- http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/04news/americans.htm

- Aminorroaya A, Amini M, Naghdi H, Zadeh AH (2003). "Growth charts of heights and weights of male children and adolescents of Isfahan, Iran". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 21 (4): 341–6. PMID 15038589.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blaha, P. et al.: 6. Celostátní antropologický výzkum dětí a mládeže 2001, Česká republika [6th Nationwide anthropological research of children and youth 2001, Czech republic], Charles University in Prague 2005

- Bogin, B.A. (1999) Patterns of human growth. 2nd ed Cambridge U Press

- Bogin, B.A. (2001) The growth of humanity Wiley-Liss

- Cavelaars, A.E.J.M., Kunst, A.E., Geurts, J.J.M., Crialesi, R., Grotvedt, L., Helmert U. Persistent variations in average height between countries and between socio-economic groups: an overview of 10 European countries. Annals of Human Biology. 27(4),407–421.

- Deurenberg P, Bhaskaran K, Lian PL (2003). "Singaporean Chinese adolescents have more subcutaneous adipose tissue than Dutch Caucasians of the same age and body mass index". Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 12 (3): 261–5. PMID 14505987.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eveleth, P.B. & Tanner, J.M. (1990) Worldwide variation in human growth, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press.

- Lintsi M, Kaarma H (2006). "Growth of Estonian seventeen-year-old boys during the last two centuries". Econ Hum Biol. 4 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2005.05.007. PMID 15993666.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Miura K, Nakagawa H, Greenland P (2002). "Invited commentary: Height-cardiovascular disease relation: where to go from here?". Am. J. Epidemiol. 155 (8): 688–9. doi:10.1093/aje/155.8.688. PMID 11943684.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ruff, C. (2002) Variation in human body size and shape. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 31:211–232.

- Average height of young Spaniards (in Spanish)

- Krishan K, Sharma JC (2002). "Intra-individual difference between recumbent length and stature among growing children". Indian J Pediatr. 69 (7): 565–9. doi:10.1007/BF02722678. PMID 12173694.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Case A, Paxson C (2008). "Stature and status: Height, ability, and labor market outcomes". The Journal of Political Economy. 116 (3): 499–532. doi:10.1086/589524. PMC 2709415. PMID 19603086.

- Sakamaki R, Amamoto R, Mochida Y, Shinfuku N, Toyama K (2005). "A comparative study of food habits and body shape perception of university students in Japan and Korea". Nutrition Journal. 4: 31. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-4-31. PMC 1298329. PMID 16255785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

References

- ^ del Pino, Mariana; Bay, Luisa; Lejarraga, Horacio; Kovalskys, Irina; Berner, Enrique; Herscovici, Cecile Rausch (2005). "Peso y estatura de una muestra nacional de 1.971 adolescentes de 10 a 19 años: las referencias argentinas continúan vigentes". Archivos argentinos de pediatría (in Spanish). 103 (4): 323–30.

- ^ a b c ABS How Australians Measure Up 1995 data

- ^ a b c d http://www.econ.upf.edu/docs/papers/downloads/1002.pdf The Evolution of Adult Height in Europe

- ^ Azerbaijan State Statistics Committee, 2005

- ^ NATIONAL NUTRITION SURVEY

- ^ IBGE(2005)

- ^ Folha de SP

- ^ Kamadjeu RM, Edwards R, Atanga JS, Kiawi EC, Unwin N, Mbanya JC (2006). "Anthropometry measures and prevalence of obesity in the urban adult population of Cameroon: an update from the Cameroon Burden of Diabetes Baseline Survey". BMC Public Health. 6: 228. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-228. PMC 1579217. PMID 16970806.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Methodological Issues in Anthropometry: Self-reported versus Measured Height and Weight, by Margot Shields, Sarah Connor Gorber, Mark S. Tremblay

- ^ Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2004

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b Yang XG, Li YP, Ma GS; et al. (2005). "[Study on weight and height of the Chinese people and the differences between 1992 and 2002]". Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi (in Chinese). 26 (7): 489–93. PMID 16334998.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A TROPICAL SUCCESS STORY: A CENTURY OF IMPROVEMENTS IN THE BIOLOGICAL STANDARD OF LIVING, COLOMBIA 1910–2002 *

- ^ a b c Productive Benefits of Improving Health: Evidence from Low-Income Countries, T. Paul Schultz*

- ^ DST Statistical Yearbook 2007

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b Pineau JC, Delamarche P, Bozinovic S (2005). "Les Alpes Dinariques : un peuple de sujets de grande taille". Comptes Rendus Biologies (in French). 328 (9): 841–6. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2005.07.004. PMID 16168365.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lintsi M, Kaarma H (2006). "Growth of Estonian seventeen-year-old boys during the last two centuries". Economics and Human Biology. 4 (1): 89–103. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2005.05.007. PMID 15993666.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ National Public Health Institute (Finland)

- ^ a b La taille des hommes : son incidence sur la vie en couple et la carrière professionnelle - INSEE

- ^ Rebecca Sear

- ^ a b Households, families and health - Results of the Microcensus 2005

- ^ Papadimitriou A, Fytanidis G, Douros K, Papadimitriou DT, Nicolaidou P, Fretzayas A (2008). "Greek young men grow taller". Acta Paediatrica. 97 (8): 1105–7. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00855.x. PMID 18477057.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A review of Hungarian studies on growth and physique of children

- ^ Angus Deaton, 2008

- ^ Times of India

- ^ Venkaiah K, Damayanti K, Nayak MU, Vijayaraghavan K (2002). "Diet and nutritional status of rural adolescents in India". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56 (11): 1119–25. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601457. PMID 12428178.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Indonesia Family Life Survey,1997

- ^ Youth Profile in Some Suburban Areas In East Java (Preliminary Survey of The Indonesian Youth Stature at The Fiftieth Anniversary of Indonesia)

- ^ a b http://diglib.tums.ac.ir/pub/magmng/pdf/6079.pdf Secular Trend of Height Variations in Iranian Population Born between 1940 and 1984

- ^ http://www.unu.edu/unupress/food/fnb23-4.pdf Relationship between waist circumference and blood pressure among the population in Baghdad,Iraq,Haifa Tawfeek

- ^ Mandel D, Zimlichman E, Mimouni FB, Grotto I, Kreiss Y (2004). "Height-related changes in body mass index: a reappraisal". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 23 (1): 51–4. PMID 14963053.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Altezza media per sesso e regione per le persone di 18-40 anni, anno 2006, Received from ISTAT 11 Feb. 2009

- ^ a b Okosun IS, Cooper RS, Rotimi CN, Osotimehin B, Forrester T (1998). "Association of waist circumference with risk of hypertension and type 2 diabetes in Nigerians, Jamaicans, and African-Americans". Diabetes Care. 21 (11): 1836–42. doi:10.2337/diacare.21.11.1836. PMID 9802730.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Official Statistics by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

- ^ Korea.net

- ^ VISUOMENĖS SVEIKATA Anthropometrical data and physical fitness of Lithuanian soldiers

- ^ Distribution of Body Weight, Height and Body Mass Index in a National Sample of Malaysian Adults

- ^ a b 2003 study. A 2007 Eurostat study revealed the same results - the average Maltese person is 164.9cm (5'4.9") compared to the EU average of 169.6 cm (5'6.7").

- ^ Msamati BC, Igbigbi PS (2000). "Anthropometric profile of urban adult black Malawians". East African Medical Journal. 77 (7): 364–8. PMID 12862154.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nutritional status of adults in rural Mali,Katherine A. Dettwyler

- ^ Indice de masa corporal y percepción de la imagen corporal en una población adulta mexicana: la precisión del autorreporte

- ^ Estudio Nacional de Salud y Envejecimiento en México (ENASEM)

- ^ [3]

- ^ a b Zelfgerapporteerde medische consumptie, gezondheid en leefstijl, Central Bureau of Statistics, 16 March 2009, accessed October 06, 2009

- ^ a b (page 60) Size and Shape of New Zealanders: NZ Norms for Anthropometric Data 1993****. Based on British norms and their relations to New Zealand values

- ^ http://www.ssb.no/english/yearbook/tab/tab-106.html Statistics Norway

- ^ Encuesta Nacional de Indicadores Nutricionales, Bioquímicos, Socioeconómicos y Culturales relacionados con las Enfermedades Crónico Degenerativas 2005

- ^ a b 6th National Nutrition Survey

- ^ Tendências do Peso em Portugal no Final do Século XX

- ^ Deurenberg et al. 2003

- ^ a b SADHS(1998)

- ^ [4]

- ^ a b Cavelaars et al 2000.

- ^ Dagens Nyheter (2008-02-29)

- ^ Rühli FJ, Henneberg M, Schaer DJ, Imhof A, Schleiffenbaum B, Woitek U (2008). "Determinants of inter-individual cholesterol level variation in an unbiased young male sample". Swiss Medical Weekly. 138 (19–20): 286–91. doi:2008/19/smw-11971. PMID 18491242.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University-Health Research Project

- ^ a b Özer, Basak Koca (2008). "Secular trend in body height and weight of Turkish adults". Anthropological Science. 116: 191. doi:10.1537/ase.061213.

- ^ Oner N, Vatansever U, Sari A; et al. (2004). "Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in Turkish adolescents". Swiss Medical Weekly. 134 (35–36): 529–33. doi:2004/35/smw-10740. PMID 15517506.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [5]

- ^ a b c Health Survey for England 2007

- ^ a b c d e Anthropometric Reference Data for Children and Adults 2003–2006

- ^ Nettle D (2002). "Women's height, reproductive success and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in modern humans". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 269 (1503): 1919–23. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2111. PMC 1691114. PMID 12350254.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Table 1. Association of 'biological' and demographic variables and height. Figures are coefficients (95% confidence intervals) adjusted for each of the variables shown". in Rona RJ, Mahabir D, Rocke B, Chinn S, Gulliford MC (2003). "Social inequalities and children's height in Trinidad and Tobago". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 57 (1): 143–50. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601508. PMID 12548309.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller, Jane E. (1993). "Birth Outcomes by Mother's Age At First Birth in the Philippines". International Family Planning Perspectives. 19 (3): 98–102.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pevalin, David J. (2003). "Outcomes in Childhood and Adulthood by Mother's Age at Birth: evidence from the 1970 British Cohort Study". ISER working papers.

- ^ a b Dr. Chao-Qiang Lai (2006). "How much of human height is genetic and how much is due to nutrition?".

- ^ R.A. Fisher (1918). "The correlation between relatives on the supposition of mendelian inheritance". Trans. R. Soc. Edinburgh: 399–433.

- ^ the tallest people in the world

- ^ climate sculpts bodies

- ^ Chali D (1995). "Anthropometric measurements of the Nilotic tribes in a refugee camp". Ethiopian Medical Journal. 33 (4): 211–7. PMID 8674486.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Samaras TT, Elrick H (2002). "Height, body size, and longevity: is smaller better for the human body?". The Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (3): 206–8. PMC 1071721. PMID 12016250.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Magnusson PK, Gunnell D, Tynelius P, Davey Smith G, Rasmussen F (2005). "Strong inverse association between height and suicide in a large cohort of Swedish men: evidence of early life origins of suicidal behavior?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (7): 1373–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1373. PMID 15994722.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Physiology of the Elite Rower".[self-published source?]

- ^ http://www.rugby.com.au/players/wallabies/2007_squad/2007_rwc_squad/gregan_george,62575.html

- ^ Gabbett T, Kelly J, Pezet T (2007). "Relationship between physical fitness and playing ability in rugby league players". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 21 (4): 1126–33. doi:10.1519/R-20936.1. PMID 18076242.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.discoverychannelasia.com/sumo/world_famous_sumos/index.shtml

- ^ Minimum height for enlistment was 5-6 http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/enlistment/index.asp]

- ^ Komlos, J. & Baur, M. From the tallest to (one of) the fattest: the enigmatic fate of the American population in the twentieth century. Economics and Human Biology, 2(1), March 2004, p 57–74.

- ^ Bogin 2001, citing height and distribution data of 8 plains Native Americans tribes collected by Frank Boas during 1888–1903 published by Prince & Steckel 1998, "Tallest in the world: Native Americans of the Great Plains in the nineteenth century". National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. Historical paper 112 1–35

- ^ Demick, Barbara. Effects of famine: Short staure evident in North Korean generation. Los Angeles Times. The Seattle Times. 2004-02-14.

- ^ P.O.V. - Big Enough . The Height Gap | PBS

- ^ Bogin B, Rios L (2003). "Rapid morphological change in living humans: implications for modern human origins". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part a, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 136 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00294-5. PMID 14527631.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- CDC National Center for Health Statistics: Growth Charts of American Percentiles

- Human Height Around the World

- www.fao.org: Body Weights and Heights by Countries (given in percentiles)

- BMI Calculator Calculate a persons Body Mass Index

- The Height Gap, Article discussing differences in height around the world

- The Western Journal of Medicine: Height, body size, and longevity

- Height Increase Methods