Pneumonia: Difference between revisions

removed as being deleted |

Uploadvirus (talk | contribs) m →Cause: Fix 3 grammar and spelling errors |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

==Cause== |

==Cause== |

||

Pneumonia can be due to microorganisms, irritants or |

Pneumonia can be due to microorganisms, irritants or unknown causes. When pneumonias are grouped this way, infectious causes are the most common. |

||

The symptoms of infectious pneumonia are caused by the invasion of the lungs by [[microorganism]]s and by the [[immune system]]'s response to the infection. Although more than one hundred strains of microorganism can cause pneumonia, only a few are responsible for most cases. The most common causes of pneumonia are [[virus]]es and [[bacteria]]. Less common causes of infectious pneumonia are [[fungi]] and [[parasites]]. |

The symptoms of infectious pneumonia are caused by the invasion of the lungs by [[microorganism]]s and by the [[immune system]]'s response to the infection. Although more than one hundred strains of microorganism can cause pneumonia, only a few are responsible for most cases. The most common causes of pneumonia are [[virus]]es and [[bacteria]]. Less common causes of infectious pneumonia are [[fungi]] and [[parasites]]. |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

===Fungi=== |

===Fungi=== |

||

{{Main|Fungal pneumonia}} |

{{Main|Fungal pneumonia}} |

||

Fungal pneumonia is uncommon, but it may occur in individuals with [[Immunodeficiency|immune system problems]] due to [[AIDS]], [[ |

Fungal pneumonia is uncommon, but it may occur in individuals with [[Immunodeficiency|immune system problems]] due to [[AIDS]], [[immunosuppressive drug]]s, or other medical problems. The pathophysiology of pneumonia caused by fungi is similar to that of bacterial pneumonia. Fungal pneumonia is most often caused by ''[[Histoplasmosis|Histoplasma capsulatum]]'', blastomyces, ''[[Cryptococcus neoformans]]'', ''[[Pneumocystis jiroveci]]'', and ''[[Coccidioides immitis]]''. [[Histoplasmosis]] is most common in the [[Mississippi embayment|Mississippi River basin]], and [[coccidioidomycosis]] in the [[southwestern United States]]. |

||

===Parasites=== |

===Parasites=== |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

{{Main|Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia}} |

{{Main|Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia}} |

||

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIP) are a class of [[diffuse lung disease]]s. While this group is called idiopathic, which means that the cause is unknown, in some types of pneumonia classified as IIPs the cause is known and the name of group is misleading. For example, [[desquamative interstitial pneumonia]] is classified as an IIP, but it is caused by [[smoking]]. Many types of IIP, such as [[usual interstitial pneumonia]] do not have a known cause. |

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIP) are a class of [[diffuse lung disease]]s. While this group is called idiopathic, which means that the cause is unknown, in some types of pneumonia classified as IIPs the cause is known and the name of the group is misleading. For example, [[desquamative interstitial pneumonia]] is classified as an IIP, but it is caused by [[smoking]]. Many types of IIP, such as [[usual interstitial pneumonia]] do not have a known cause. |

||

==Diagnosis== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

Revision as of 12:32, 18 April 2011

| Pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Pulmonology, infectious diseases |

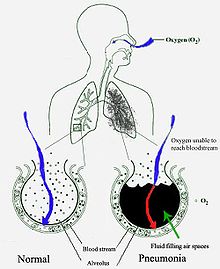

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung, especially inflammation of the alveoli (microscopic air sacs in the lungs) or when the lungs fill with fluid (called consolidation and exudation).[1][2]

There are many causes of pneumonia. Infection is the most common cause, and may involve bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites. Chemical burns or physical injury to the lungs can also produce pneumonia.

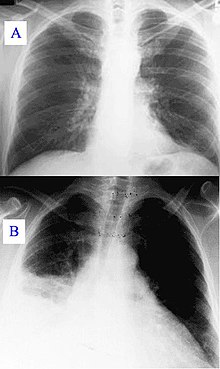

Typical symptoms associated with pneumonia include cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty in breathing. Diagnostic tools include x-rays and examination of the sputum. Treatment depends on the cause of pneumonia; bacterial pneumonia is treated with antibiotics.

Pneumonia is a common disease that occurs in all age groups. It is a leading cause of death among the young, the old, and the chronically ill.[3] Vaccines to prevent certain types of pneumonia are available. The prognosis depends on the type of pneumonia, the treatment, any complications, and the person's underlying health.

Signs and symptoms

People with infectious pneumonia often have a cough producing greenish or yellow sputum or phlegm and a high fever that may be accompanied by shaking chills. Shortness of breath is also common, as is sharp or stabbing chest pain during deep breaths or coughs. Less frequent symptoms of pneumonia include coughing up blood, headaches, sweaty and clammy skin, loss of appetite, fatigue, blueness of the skin, nausea, vomiting, mood swings, and joint pains or muscle aches. Some forms of pneumonia can cause specific symptoms. Pneumonia caused by Legionella may cause abdominal pain and diarrhea, while pneumonia caused by tuberculosis or Pneumocystis may cause only weight loss and night sweats. Symptoms in the elderly can include new or worsening confusion (delirium) or may experience unsteadiness, leading to falls. Infants with pneumonia may have many of the symptoms above, but in many cases they are simply sleepy or have a decreased appetite.[4]

Physical examination may reveal signs of illness including fever or sometimes low body temperature, an increased respiratory rate, low blood pressure, a high heart rate, or a low oxygen saturation, which is the amount of oxygen in the blood as indicated by either pulse oximetry or blood gas analysis. Struggling to breathe, confusion, and blue-tinged skin are signs of a medical emergency.

Findings from physical examination of the lungs may be normal, but often show decreased expansion of the chest on the affected side. Harsher sounds from the larger airways transmitted through the inflamed lung are heard as bronchial breathing on auscultation with a stethoscope. Rales (or crackles) may be heard over the affected area during inspiration. Percussion may be dulled over the affected lung, and increased rather than decreased vocal resonance distinguishes pneumonia from a pleural effusion.[4] Because some of these signs are subjective, physical examination alone is insufficient to diagnose or rule out pneumonia.[5][6]

Cause

Pneumonia can be due to microorganisms, irritants or unknown causes. When pneumonias are grouped this way, infectious causes are the most common.

The symptoms of infectious pneumonia are caused by the invasion of the lungs by microorganisms and by the immune system's response to the infection. Although more than one hundred strains of microorganism can cause pneumonia, only a few are responsible for most cases. The most common causes of pneumonia are viruses and bacteria. Less common causes of infectious pneumonia are fungi and parasites.

Viruses

Viruses have been found to account for between 18—28% of pneumonia in a few limited studies.[7] Viruses invade cells in order to reproduce. Typically, a virus reaches the lungs when airborne droplets are inhaled through the mouth and nose. Once in the lungs, the virus invades the cells lining the airways and alveoli. This invasion often leads to cell death, either when the virus directly kills the cells, or through a type of cell controlled self-destruction called apoptosis. When the immune system responds to the viral infection, even more lung damage occurs. White blood cells, mainly lymphocytes, activate certain chemical cytokines which allow fluid to leak into the alveoli. This combination of cell destruction and fluid-filled alveoli interrupts the normal transportation of oxygen into the bloodstream.

As well as damaging the lungs, many viruses affect other organs and thus disrupt many body functions. Viruses can also make the body more susceptible to bacterial infections; for which reason bacterial pneumonia may complicate viral pneumonia.[7]

Viral pneumonia is commonly caused by viruses such as influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, and parainfluenza.[7] Herpes simplex virus is a rare cause of pneumonia except in newborns. People with weakened immune systems are also at risk of pneumonia caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Bacteria

Bacteria are the most common cause of community acquired pneumonia with Streptococcus pneumoniae the most commonly isolated bacteria.[8] Another important Gram-positive cause of pneumonia is Staphylococcus aureus, with Streptococcus agalactiae being an important cause of pneumonia in newborn babies. Gram-negative bacteria cause pneumonia less frequently than gram-positive bacteria. Some of the gram-negative bacteria that cause pneumonia include Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Moraxella catarrhalis. These bacteria often live in the stomach or intestines and may enter the lungs if vomit is inhaled. "Atypical" bacteria which cause pneumonia include Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila.

Bacteria typically enter the lung when airborne droplets are inhaled, but can also reach the lung through the bloodstream when there is an infection in another part of the body. Many bacteria live in parts of the upper respiratory tract, such as the nose, mouth and sinuses, and can easily be inhaled into the alveoli. Once inside, bacteria may invade the spaces between cells and between alveoli through connecting pores. This invasion triggers the immune system to send neutrophils, a type of defensive white blood cell, to the lungs. The neutrophils engulf and kill the offending organisms, and also release cytokines, causing a general activation of the immune system. This leads to the fever, chills, and fatigue common in bacterial and fungal pneumonia. The neutrophils, bacteria, and fluid from surrounding blood vessels fill the alveoli and interrupt normal oxygen transportation.

Fungi

Fungal pneumonia is uncommon, but it may occur in individuals with immune system problems due to AIDS, immunosuppressive drugs, or other medical problems. The pathophysiology of pneumonia caused by fungi is similar to that of bacterial pneumonia. Fungal pneumonia is most often caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, blastomyces, Cryptococcus neoformans, Pneumocystis jiroveci, and Coccidioides immitis. Histoplasmosis is most common in the Mississippi River basin, and coccidioidomycosis in the southwestern United States.

Parasites

A variety of parasites can affect the lungs. These parasites typically enter the body through the skin or by being swallowed. Once inside, they travel to the lungs, usually through the blood. There, as in other cases of pneumonia, a combination of cellular destruction and immune response causes disruption of oxygen transportation. One type of white blood cell, the eosinophil, responds vigorously to parasite infection. Eosinophils in the lungs can lead to eosinophilic pneumonia, thus complicating the underlying parasitic pneumonia. The most common parasites causing pneumonia are Toxoplasma gondii, Strongyloides stercoralis, and Ascariasis.

Idiopathic

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIP) are a class of diffuse lung diseases. While this group is called idiopathic, which means that the cause is unknown, in some types of pneumonia classified as IIPs the cause is known and the name of the group is misleading. For example, desquamative interstitial pneumonia is classified as an IIP, but it is caused by smoking. Many types of IIP, such as usual interstitial pneumonia do not have a known cause.

Diagnosis

If pneumonia is suspected on the basis of a patient's symptoms and findings from physical examination, further investigations are needed to confirm the diagnosis. Information from a chest X-ray and blood tests are helpful, and sputum cultures in some cases. The chest X-ray is typically used for diagnosis in hospitals and some clinics with X-ray facilities. However, in a community setting (general practice), pneumonia is usually diagnosed based on symptoms and physical examination alone.[citation needed] Diagnosing pneumonia can be difficult in some people, especially those who have other illnesses. Occasionally a chest CT scan or other tests may be needed to distinguish pneumonia from other illnesses.

Classification

Pneumonia can be classified in several ways, most commonly by where it was acquired (hospital verses community), but may also by the area of lung affected or by the causative organism.[9] There is also a combined clinical classification, which combines factors such as age, risk factors for certain microorganisms, the presence of underlying lung disease or systemic disease, and whether the person has recently been hospitalized.

Investigations

An important test for pneumonia in unclear situations is a chest x-ray. Chest x-rays can reveal areas of opacity (seen as white) which represent consolidation. Pneumonia is not always seen on x-rays, either because the disease is only in its initial stages, or because it involves a part of the lung not easily seen by x-ray. In some cases, chest CT (computed tomography) can reveal pneumonia that is not seen on chest x-ray. X-rays can be misleading, because other problems, like lung scarring and congestive heart failure, can mimic pneumonia on x-ray.[10] Chest x-rays are also used to evaluate for complications of pneumonia (see below.)

If antibiotics fail to improve the patient's health, or if the health care provider has concerns about the diagnosis, a culture of the person's sputum may be requested. Sputum cultures generally take at least two to three days, so they are mainly used to confirm that the infection is sensitive to an antibiotic that has already been started. A blood sample may similarly be cultured to look for bacteria in the blood. Any bacteria identified are then tested to see which antibiotics will be most effective.

A complete blood count may show a high white blood cell count, indicating the presence of an infection or inflammation. In some people with immune system problems, the white blood cell count may appear deceptively normal. Blood tests may be used to evaluate kidney function (important when prescribing certain antibiotics) or to look for low blood sodium. Low blood sodium in pneumonia is thought to be due to extra anti-diuretic hormone produced when the lungs are diseased (SIADH). Specific blood serology tests for other bacteria (Mycoplasma, Legionella and Chlamydophila) and a urine test for Legionella antigen are available. Respiratory secretions can also be tested for the presence of viruses such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus. Liver function tests should be carried out to test for damage caused by sepsis.[4]

Combining findings

One study created a prediction rule that found the five following signs best predicted infiltrates on the chest radiograph of 1134 patients presenting to an emergency room:[11]

- Fever > 37.8 °C (100.0 °F)

- Pulse > 100 beats/min

- Rales/crackles

- Decreased breath sounds

- Absence of asthma

The probability of an infiltrate in two separate validations was based on the number of findings:

- 5 findings – 84% to 91% probability

- 4 findings – 58% to 85%

- 3 findings – 35% to 51%

- 2 findings – 14% to 24%

- 1 findings – 5% to 9%

- 0 findings – 2% to 3%

A subsequent study[12] comparing four prediction rules to physician judgment found that two rules, the one above[11] and also[13] were more accurate than physician judgment because of the increased specificity of the prediction rules.

Differential diagnosis

Several diseases and/or conditions can present with similar clinical features to pneumonia. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma can present with a polyphonic wheeze, similar to that of pneumonia. Pulmonary edema can be mistaken for pneumonia (and vice versa), especially in the elderly, due to its similar symptoms and signs. Other diseases to be taken into consideration include bronchiectasis, lung cancer and pulmonary emboli.[4]

Prevention

There are several ways to prevent infectious pneumonia. Appropriately treating underlying illnesses (such as AIDS) can decrease a person's risk of pneumonia. Smoking cessation is important not only because it helps to limit lung damage, but also because cigarette smoke interferes with many of the body's natural defenses against pneumonia.

Research shows that there are several ways to prevent pneumonia in newborn infants. Testing pregnant women for Group B Streptococcus and Chlamydia trachomatis, and then giving antibiotic treatment if needed, reduces pneumonia in infants. Suctioning the mouth and throat of infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid decreases the rate of aspiration pneumonia.

Vaccination is important for preventing pneumonia in both children and adults. Vaccinations against Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae in the first year of life have greatly reduced the role these bacteria play in causing pneumonia in children. Vaccinating children against Streptococcus pneumoniae has also led to a decreased incidence of these infections in adults because many adults acquire infections from children. Hib vaccine is now widely used around the globe. The childhood pneumococcal vaccine is still as of 2009 predominantly used in high-income countries, though this is changing. In 2009, Rwanda became the first low-income country to introduce pneumococcal conjugate vaccine into their national immunization program.[14]

A vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae is also available for adults. In the U.S., it is currently recommended for all healthy individuals older than 65 and any adults with emphysema, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis of the liver, alcoholism, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or those who do not have a spleen. A repeat vaccination may also be required after five or ten years.[15]

Influenza vaccines should be given yearly to the same individuals who receive vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae. In addition, health care workers, nursing home residents, and pregnant women should receive the vaccine.[16] When an influenza outbreak is occurring, medications such as amantadine, rimantadine, zanamivir, and oseltamivir can help prevent influenza.[17][18]

Treatment

In the United States more than 80% of cases of community acquired pneumonia are treated without hospitalization.[8] Typically, oral antibiotics, rest, fluids, and home care are sufficient for complete resolution. However, people who are having trouble breathing, with other medical problems, and the elderly may need greater care. If the symptoms get worse, the pneumonia does not improve with home treatment, or complications occur, then hospitalization may be recommended. Over the counter cough medicine has not been found to be helpful in pneumonia.[19]

Bacterial

Antibiotics improve outcomes in those with bacterial pneumonia.[20] Initially antibiotic choice depends on the characteristics of the person affected such as age, underlying health, and location the infection was acquired.

In the UK empiric treatment is usually with amoxicillin, erythromycin, or azithromycin for community-acquired pneumonia.[21] In North America, where the "atypical" forms of community-acquired pneumonia are becoming more common, macrolides (such as azithromycin), and doxycycline have displaced amoxicillin as first-line outpatient treatment for community-acquired pneumonia.[8][22] The use of fluoroquinolones in uncomplicated cases is discouraged due to concerns of side effects and resistance.[8] The duration of treatment has traditionally been seven to ten days, but there is increasing evidence that short courses (three to five days) are equivalent.[23] Antibiotics recommended for hospital-acquired pneumonia include third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and vancomycin.[24] These antibiotics are often given intravenously and may be used in combination.

Viral

No specific treatments exist for most types of viral pneumonia including SARS coronavirus, adenovirus, hantavirus, and parainfluenza virus with the exception of influenza A and influenza B. Influenza A may be treated with rimantadine or amantadine while influenza A or B may be treated with oseltamivir or zanamivir. These are beneficial only if they are started within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. Many strains of H5N1 influenza A, also known as avian influenza or "bird flu," have shown resistance to rimantadine and amantadine.

Aspiration

There is no evidence to support the use of antibiotics in chemical pneumonitis without bacterial superinfection. If infection is present in aspiration pneumonia, the choice of antibiotic will depend on several factors, including the suspected causative organism and whether pneumonia was acquired in the community or developed in a hospital setting. Common options include clindamycin, a combination of a beta-lactam antibiotic and metronidazole, or an aminoglycoside.[25] Corticosteroids are commonly used in aspiration pneumonia, but there is no evidence to support their use either.[25]

Prognosis

With treatment, most types of bacterial pneumonia can be cleared within two to four weeks.[26] Viral pneumonia may last longer, and mycoplasmal pneumonia may take four to six weeks to resolve completely.[26] The eventual outcome of an episode of pneumonia depends on how ill the person is when he or she is first diagnosed.[26]

In the United States, about one of every twenty people with pneumococcal pneumonia die. In cases where the pneumonia progresses to blood poisoning (bacteremia), just over 20% of sufferers die.[27]

The death rate (or mortality) also depends on the underlying cause of the pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma, for instance, is associated with little mortality. However, about half of the people who develop methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia while on a ventilator will die.[28] In regions of the world without advanced health care systems, pneumonia is even deadlier. Limited access to clinics and hospitals, limited access to x-rays, limited antibiotic choices, and inability to treat underlying conditions inevitably leads to higher rates of death from pneumonia. For these reasons, the majority of deaths in children under five due to pneumococcal disease occur in developing countries.[29]

Adenovirus can cause severe necrotizing pneumonia in which all or part of a lung has increased translucency radiographically, which is called Swyer-James Syndrome.[30] Severe adenovirus pneumonia also may result in bronchiolitis obliterans, a subacute inflammatory process in which the small airways are replaced by scar tissue, resulting in a reduction in lung volume and lung compliance.[30] Sometimes pneumonia can lead to additional complications. Complications are more frequently associated with bacterial pneumonia than with viral pneumonia. The most important complications include respiratory and circulatory failure and pleural effusions, empyema or abscesses.

Clinical prediction rules

Clinical prediction rules have been developed to more objectively prognosticate outcomes in pneumonia. These rules can be helpful in deciding whether or not to hospitalize the person.

- Pneumonia severity index (or PORT Score)[31] – online calculator

- CURB-65 score, which takes into account the severity of symptoms, any underlying diseases, and age[32] – online calculator

Respiratory and circulatory failure

Because pneumonia affects the lungs, often people with pneumonia have difficulty breathing, and it may not be possible for them to breathe well enough to stay alive without support. Non-invasive breathing assistance may be helpful, such as with a bi-level positive airway pressure machine. In other cases, placement of an endotracheal tube (breathing tube) may be necessary, and a ventilator may be used to help the person breathe.

Pneumonia can also cause respiratory failure by triggering acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which results from a combination of infection and inflammatory response. The lungs quickly fill with fluid and become very stiff. This stiffness, combined with severe difficulties extracting oxygen due to the alveolar fluid, create a need for mechanical ventilation.

Sepsis and septic shock are potential complications of pneumonia. Sepsis occurs when microorganisms enter the bloodstream and the immune system responds by secreting cytokines. Sepsis most often occurs with bacterial pneumonia; Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause. Individuals with sepsis or septic shock need hospitalization in an intensive care unit. They often require intravenous fluids and medications to help keep their blood pressure from dropping too low. Sepsis can cause liver, kidney, and heart damage, among other problems, and it often causes death.

Pleural effusion, empyema, and abscess

Occasionally, microorganisms infecting the lung will cause fluid (a pleural effusion) to build up in the space that surrounds the lung (the pleural cavity). If the microorganisms themselves are present in the pleural cavity, the fluid collection is called an empyema. When pleural fluid is present in a person with pneumonia, the fluid can often be collected with a needle (thoracentesis) and examined. Depending on the results of this examination, complete drainage of the fluid may be necessary, often requiring a chest tube. In severe cases of empyema, surgery may be needed. If the fluid is not drained, the infection may persist, because antibiotics do not penetrate well into the pleural cavity.

Rarely, bacteria in the lung will form a pocket of infected fluid called an abscess. Lung abscesses can usually be seen with a chest x-ray or chest CT scan. Abscesses typically occur in aspiration pneumonia and often contain several types of bacteria. Antibiotics are usually adequate to treat a lung abscess, but sometimes the abscess must be drained by a surgeon or radiologist.

Epidemiology

Pneumonia is a common illness in all parts of the world. It is a major cause of death among all age groups and is the leading cause of death in children in low income countries.[20] In children, many of these deaths occur in the newborn period. The World Health Organization estimates that one in three newborn infant deaths are due to pneumonia.[33] Over two million children under five die each year worldwide and it is estimated that up to 1 million of these (vaccine preventable) deaths are caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, and over 90% of these deaths take place in developing countries.[34] Mortality from pneumonia generally decreases with age until late adulthood with increased mortality in the elderly.

In the United Kingdom, the annual incidence of pneumonia is approximately 6 cases for every 1000 people for the 18–39 age group. For those over 75 years of age, this rises to 75 cases for every 1000 people. Roughly 20–40% of individuals who contract pneumonia require hospital admission of which between 5–10% are admitted to a critical care unit. The mortality rate in the UK is around 5–10%.[4] In the United States community acquired pneumonia affects 5.6 million people a year making it the 6th leading cause of death.[8]

More cases of pneumonia occur during the winter months than during other times of the year. Pneumonia occurs more commonly in males than females, and more often in Blacks than Caucasians due to differences in synthesizing Vitamin D from sunlight. Individuals with underlying illnesses such as Alzheimer's disease, cystic fibrosis, emphysema, tobacco smoking, alcoholism, or immune system problems are at increased risk for pneumonia.[35] These individuals are also more likely to have repeated episodes of pneumonia. People who are hospitalized for any reason are also at high risk for pneumonia.

History

The symptoms of pneumonia were described by Hippocrates (c. 460 BC – 370 BC):

Peripneumonia, and pleuritic affections, are to be thus observed: If the fever be acute, and if there be pains on either side, or in both, and if expiration be if cough be present, and the sputa expectorated be of a blond or livid color, or likewise thin, frothy, and florid, or having any other character different from the common... When pneumonia is at its height, the case is beyond remedy if he is not purged, and it is bad if he has dyspnoea, and urine that is thin and acrid, and if sweats come out about the neck and head, for such sweats are bad, as proceeding from the suffocation, rales, and the violence of the disease which is obtaining the upper hand.[36]

However, Hippocrates referred to pneumonia as a disease "named by the ancients." He also reported the results of surgical drainage of empyemas. Maimonides (1138–1204 AD) observed "The basic symptoms which occur in pneumonia and which are never lacking are as follows: acute fever, sticking [pleuritic] pain in the side, short rapid breaths, serrated pulse and cough."[37] This clinical description is quite similar to those found in modern textbooks, and it reflected the extent of medical knowledge through the Middle Ages into the 19th century.

Bacteria were first seen in the airways of individuals who died from pneumonia by Edwin Klebs in 1875.[38] Initial work identifying the two common bacterial causes Streptococcus pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae was performed by Carl Friedländer[39] and Albert Fränkel[40] in 1882 and 1884, respectively. Friedländer's initial work introduced the Gram stain, a fundamental laboratory test still used to identify and categorize bacteria. Christian Gram's paper describing the procedure in 1884 helped differentiate the two different bacteria and showed that pneumonia could be caused by more than one microorganism.[41]

Sir William Osler, known as "the father of modern medicine," appreciated the morbidity and mortality of pneumonia, describing it as the "captain of the men of death" in 1918, as it had overtaken tuberculosis as one of the leading causes of death in his time. (The phrase was originally coined by John Bunyan with regard to consumption, or tuberculosis.[42]) However, several key developments in the 1900s improved the outcome for those with pneumonia. With the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics, modern surgical techniques, and intensive care in the twentieth century, mortality from pneumonia, which had approached 30%, dropped precipitously in the developed world. Vaccination of infants against Haemophilus influenzae type b began in 1988 and led to a dramatic decline in cases shortly thereafter.[43] Vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae in adults began in 1977 and in children began in 2000, resulting in a similar decline.[44]

Society and culture

Because of the very high burden of disease in developing countries and because of a relatively low awareness of the disease in industrialized countries, the global health community has declared November 2 to be World Pneumonia Day, a day for concerned citizens and policy makers to take action against the disease.[1]

References

- ^ Template:EMedicineDictionary

- ^ "pneumonia" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "Causes of death in neonates and children under five in the world (2004)" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Hoare Z, Lim WS (2006). "Pneumonia: update on diagnosis and management". BMJ. 332 (7549): 1077–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1077. PMC 1458569. PMID 16675815.

- ^ Metlay JP, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ (1997). "Does this patient have community-acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination" (PDF). JAMA. 278 (17): 1440–5. doi:10.1001/jama.278.17.1440. PMID 9356004.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wipf JE, Lipsky BA, Hirschmann JV; et al. (1999). "Diagnosing pneumonia by physical examination: relevant or relic?". Arch. Intern. Med. 159 (10): 1082–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.10.1082. PMID 10335685.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Figueiredo LT (2009). "Viral pneumonia: epidemiological, clinical, pathophysiological and therapeutic aspects". J Bras Pneumol. 35 (9): 899–906. PMID 19820817.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Anevlavis S, Bouros D (2010). "Community acquired bacterial pneumonia". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 11 (3): 361–74. doi:10.1517/14656560903508770. PMID 20085502.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dunn, L (2005 Jun 29-Jul 5). "Pneumonia: classification, diagnosis and nursing management". Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 19 (42): 50–4. PMID 16013205.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Syrjälä H, Broas M, Suramo I, Ojala A, Lähde S (1998). "High-resolution computed tomography for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia" (PDF). Clin. Infect. Dis. 27 (2): 358–63. doi:10.1086/514675. PMID 9709887.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Heckerling PS, Tape TG, Wigton RS; et al. (1990). "Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates". Ann. Intern. Med. 113 (9): 664–70. PMID 2221647.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emerman CL, Dawson N, Speroff T; et al. (1991). "Comparison of physician judgment and decision aids for ordering chest radiographs for pneumonia in outpatients". Annals of emergency medicine. 20 (11): 1215–9. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81474-X. PMID 1952308.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gennis P, Gallagher J, Falvo C, Baker S, Than W (1989). "Clinical criteria for the detection of pneumonia in adults: guidelines for ordering chest roentgenograms in the emergency department". The Journal of emergency medicine. 7 (3): 263–8. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(89)90358-2. PMID 2745948.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ PneumoADIP. Vaccine Introduction: Rwanda.

- ^ Butler JC, Breiman RF, Campbell JF, Lipman HB, Broome CV, Facklam RR (1993). "Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine efficacy. An evaluation of current recommendations". JAMA. 270 (15): 1826–31. doi:10.1001/jama.270.15.1826. PMID 8411526.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 48 (RR-4): 1–28. 1999. PMID 10366138.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ Jefferson T, Deeks JJ, Demicheli V, Rivetti D, Rudin M (2004). "Amantadine and rimantadine for preventing and treating influenza A in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001169. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001169.pub2. PMID 15266442.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayden FG, Atmar RL, Schilling M; et al. (1999). "Use of the selective oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir to prevent influenza". N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (18): 1336–43. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411802. PMID 10536125.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chang CC, Cheng AC, Chang AB (2007). "Over-the-counter (OTC) medications to reduce cough as an adjunct to antibiotics for acute pneumonia in children and adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD006088. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006088.pub2. PMID 17943884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kabra SK, Lodha R, Pandey RM (2010). "Antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD004874. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004874.pub3. PMID 20238334.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "2004 Pneumonia Guideline – Synopsis" (PDF). p. iv5.

- ^ Lutfiyya MN, Henley E, Chang LF, Reyburn SW (2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia". Am Fam Physician. 73 (3): 442–50. PMID 16477891.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scalera NM, File TM (2007). "How long should we treat community-acquired pneumonia?". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 20 (2): 177–81. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3280555072. PMID 17496577.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America (2005). "Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 171 (4): 388–416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. PMID 15699079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b O'Connor S (2003). "Aspiration pneumonia and pneumonitis". Australian Prescriber. 26 (1): 14–7.

- ^ a b c Pneumonia, Bacterial at eMedicine, specifically, "The chest radiograph usually clears within 4 weeks in patients younger than 50 years without underlying pulmonary disease". Symptoms are often resolved within 1–2 weeks.]

- ^ Mufson, MA (1999-07-26). "Bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in one American City: a 20-year longitudinal study, 1978–1997". Am J Med. 107 (1A). Department of Medicine, Marshall University School of Medicine: 34S–43S. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00098-4. PMID 10451007.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Combes A, Luyt CE, Fagon JY; et al. (2004). "Impact of methicillin resistance on outcome of Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170 (7): 786–92. doi:10.1164/rccm.200403-346OC. PMID 15242840.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization. Acute Respiratory Infections: Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- ^ a b Kliegman, Robert; Richard M Kliegman (2006). Nelson essentials of pediatrics. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-8089-2325-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM; et al. (1997). "A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia". N. Engl. J. Med. 336 (4): 243–50. doi:10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. PMID 8995086.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R; et al. (2003). "Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study". Thorax. 58 (5): 377–82. doi:10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. PMC 1746657. PMID 12728155.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Garenne M, Ronsmans C, Campbell H (1992). "The magnitude of mortality from acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years in developing countries". World Health Stat Q. 45 (2–3): 180–91. PMID 1462653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ WHO (1999). "Pneumococcal vaccines. WHO position paper". Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 74 (23): 177–83. PMID 10437429.

- ^ Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Balanzó X, González CA (1999). "Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based case-control study". Eur. Respir. J. 13 (2): 349–55. doi:10.1183/09031936.99.13234999. PMID 10065680.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hippocrates On Acute Diseases wikisource link

- ^ Maimonides, Fusul Musa ("Pirkei Moshe").

- ^ Klebs E (1875-12-10). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der pathogenen Schistomyceten. VII Die Monadinen". Arch. Exptl. Pathol. Parmakol. 4 (5/6): 40–488.

- ^ Friedländer C (1882-02-04). "Über die Schizomyceten bei der acuten fibrösen Pneumonie". Virchow's Arch pathol. Anat. U. Physiol. 87 (2): 319–324. doi:10.1007/BF01880516.

- ^ Fraenkel A (1884-04-21). "Über die genuine Pneumonie, Verhandlungen des Congress für innere Medicin". Dritter Congress. 3: 17–31.

- ^ Gram C (1884-03-15). "Über die isolierte Färbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt- und Trocken-präparaten". Fortschr. Med. 2 (6): 185–9.

- ^ William Osler, Thomas McCrae (1920). The principles and practice of medicine: designed for the use of practitioners and students of medicine (9th ed.). D. Appleton. p. 78.

One of the most widespread and fatal of all acute diseases, pneumonia has become the "Captain of the Men of Death," to use the phrase applied by John Bunyan to consumption.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Adams WG, Deaver KA, Cochi SL; et al. (1993). "Decline of childhood Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease in the Hib vaccine era". JAMA. 269 (2): 221–6. doi:10.1001/jama.269.2.221. PMID 8417239.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J; et al. (2003). "Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (18): 1737–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022823. PMID 12724479.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)