Open-source hardware: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→See also: Added OSHUG |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

*[[Open Source Appropriate Technology]] - open source hardware specifically focusing on [[appropriate technology]] for [[sustainable development]] |

*[[Open Source Appropriate Technology]] - open source hardware specifically focusing on [[appropriate technology]] for [[sustainable development]] |

||

*[[Open source software]] |

*[[Open source software]] |

||

*[[OSHUG]] - the UK Open Source Hardware User Group |

|||

*[[Patent]] |

*[[Patent]] |

||

*[[Peer production]] |

*[[Peer production]] |

||

Revision as of 08:23, 17 May 2012

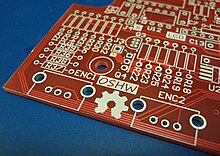

Open source hardware (OSHW) consists of physical artifacts of technology designed and offered in the same manner as free and open source software (FOSS). Open source hardware is part of the open source culture movement and applies a like concept to a variety of components. The term usually means that information about the hardware is easily discerned. Hardware design (i.e. mechanical drawings, schematics, bill of materials, PCB layout data, HDL source code and integrated circuit layout data), in addition to the software that drives the hardware, are all released with the FOSS approach.

Since the rise of reconfigurable programmable logic devices, sharing of logic designs has been a form of open source hardware. Instead of the schematics, hardware description language (HDL) code is shared. HDL descriptions are commonly used to set up system-on-a-chip systems either in field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA) or directly in application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) designs. HDL modules, when distributed, are called semiconductor intellectual property cores, or IP cores.

Licenses

Rather than creating a new license, some open source hardware projects simply use existing, free and open source software licenses.[7]

Additionally, several new licenses have been proposed. These licenses are designed to address issues specific to hardware designs.[8] In these licenses, many of the fundamental principles expressed in open source software (OSS) licenses have been "ported" to their counterpart hardware projects. Organizations tend to rally around a shared license. For example, Opencores prefers the LGPL,[9] FreeCores insists on the GPL,[10] Open Hardware Foundation promotes "copyleft" or other permissive licenses",[11] the Open Graphics Project uses a variety of licenses, including the MIT license, GPL, and a proprietary license,[12] and the Balloon Project wrote their own license.[13] New hardware licenses are often explained as the "hardware equivalent" of a well-known OSS license, such as the GPL, LGPL, or BSD license.

Despite superficial similarities to software licenses, most hardware licenses are fundamentally different: by nature, they typically rely more heavily on patent law than on copyright law. Whereas a copyright license may control the distribution of the source code or design documents, a patent license may control the use and manufacturing of the physical device built from the design documents. This distinction is explicitly mentioned in the preamble of the TAPR Open Hardware License.

- "...those who benefit from an OHL design may not bring lawsuits claiming that design infringes their patents or other intellectual property."[14]

Noteworthy licenses

- The TAPR Open Hardware License: drafted by attorney John Ackermann, reviewed by OSS community leaders Bruce Perens and Eric S. Raymond, and discussed by hundreds of volunteers in an open community discussion[15]

- Balloon Open Hardware License: used by all projects in the Balloon Project

- Although originally a software license, OpenCores encourages the LGPL

- Hardware Design Public License: written by Graham Seaman, admin. of Opencollector.org

- In March 2011 CERN released the CERN Open Hardware License (OHL)[16] intended for use with the Open Hardware Repository and other projects.

- [The Solderpad License][7] is a version of the Apache License version 2.0, amended by lawyer Andrew Katz to render it more appropriate for hardware use.

Development

Extensive discussion has taken place on ways to make open source hardware as accessible as open source software. Discussions focus on multiple areas,[17] such as the level at which open source hardware is defined,[18] ways to collaborate in hardware development, as well as a model for sustainable development.[19][20]

One of the major differences between developing open source software and developing open source hardware is that hardware results in tangible outputs, which cost money to prototype and manufacture. As a result, the phrase "free as in speech, not as in beer",[21] more formally known as Gratis versus Libre, distinguishes between the idea of zero cost and the freedom to use and modify information. While open source hardware faces challenges in minimizing cost and reducing financial risks for individual project developers, some community members have proposed models to address these needs.[22] Given this, there are initiatives to develop sustainable community funding mechanisms, such as the Open Source Hardware Central Bank,[23] as well as tools like KiCAD to make schematic development more accessible to more users.

Often vendors of chips and other electronic components will sponsor contests with the proviso that the participants and winners must share their designs. Circuit Cellar magazine organizes some of these contests.

Business models

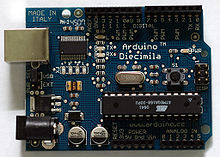

Open hardware companies are experimenting with different business models. Arduino, for example, makes money largely through design consulting. By creating a design community around their products, they stay in touch with the latest developments. They have also registered their name as a trademark. Others may manufacture their designs, but they can't put the Arduino name on them. Thus they can distinguish their products from others by quality.[24]

See also

- List of open source hardware projects

- Amateur radio and Amateur television

- Commons-based peer production

- Creative Barcode

- DIY

- Electronic design automation

- Engineers Without Borders

- FreeCAD (software)

- Free content

- Free software

- Graphics hardware and FOSS

- Homebrew Computer Club

- Open CASCADE - software development platform freely available in open source.

- Open content

- Open design - Open-source physical design with a wider focus

- Open source

- Open source ecology - Free farming machines

- Open-source robotics

- Open Source Appropriate Technology - open source hardware specifically focusing on appropriate technology for sustainable development

- Open source software

- OSHUG - the UK Open Source Hardware User Group

- Patent

- Peer production

References

- ^ http://blog.makezine.com/archive/2010/08/milkymist_interactive_vj_station.html

- ^ http://www.milkymist.org/mmsoc.html

- ^ http://belogic.com/uzebox/

- ^ http://www.worldchanging.com/archives/009340.html

- ^ http://www.techcrunch.com/2007/11/01/first-pics-of-bug-labs-open-source-hardware/

- ^ http://www.wired.com/gadgetlab/tag/zoybar/

- ^ From OpenCollector's "License Zone": GPL used by Free Model Foundry and ESA Sparc; other licenses used by Free-IP Project, LART (defunct), GNUBook (defunct).

- ^ For a nearly-comprehensive list of licenses, see OpenCollector's "license zone"

- ^ Item #2.4 "Who owns opencores?", from Opencores.org FAQ, retrieved 25 November 2008

- ^ FreeCores Main Page, retrieved 25 November 2008

- ^ Open Hardware Foundation, main page, retrieved 25 November 2008

- ^ See "Are we going to get the 'source' for what is on the FPGA also?" in the Open Graphics Project FAQ, retrieved 25 November 2008

- ^ Balloon License, from balloonboard.org

- ^ TAPR Open Hardware License website; see also the license text itself, both retrieved 25 November 2008

- ^ transcript of all comments, hosted on technocrat.net

- ^ http://www.ohwr.org/cernohl

- ^ [1], Writings on Open Source Hardware

- ^ [2] MAKE: Blog: Open source hardware, what is it? Here's a start...

- ^ [3], Halfbakery: Open Source Hardware Initiative

- ^ J. M Pearce, C. Morris Blair, K. J. Laciak, R. Andrews, A. Nosrat and I. Zelenika-Zovko, "3-D Printing of Open Source Appropriate Technologies for Self-Directed Sustainable Development", Journal of Sustainable Development 3(4), pp. 17-29 (2010)

- ^ [4]"Free, as in Beer", by Lawrence Lessig, Wired

- ^ [5], Business Models for Open Source Hardware Design

- ^ [6], from "Make: Online : The Open Source Hardware Bank, retrieved 26 April 2010

- ^ Clive Thompson, “Build It. Share It. Profit. Can Open Source Hardware Work?”, Wired Magazine, October 2008

External links

- Open Source Semiconductor Core Licensing, 25 Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 131 (2011) Article analyzing the law, technology and business of open source semiconductor cores

- Definition of Open source hardware at freedomdefined.org

- P2P Foundation: Open Hardware Directory

- Openpicus Open Source Wireless platform for smart sensors and internet of things

- Database of Open-source hardware writings at Open Collector

- Open Source Everywhere Wired

- Build It. Share It. Profit. Can Open Source Hardware Work? Wired

- Richard Stallman -- On "Free Hardware" (LinuxToday)

- Open Sesame! (Reports), The Economist

- Business models for Open Hardware

- oshug.org Open Source Hardware User Group

- Open Source Hardware and Design Alliance

- explanation of OSHW for the uninitiated (dead link)

- Open Source CNC Hardware Community