Stephen Hawking: Difference between revisions

Carcharoth (talk | contribs) →Awards and honours: tweak wording ('won' is not encyclopedic wording) |

→1975–present: add with citation |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

|accessdate=1 October 2009}}</ref> Hawking's inaugural lecture as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics was titled: "Is the end in sight for Theoretical Physics" and promoted the idea that [[supergravity]] would help solve many of the outstanding problems physicists were studying.{{sfn|Ferguson|2011|pp=93–94}} In 1982, Hawking participated in the three-week Nuffield Workshop on the Very Early Universe at Cambridge University.<ref>See Guth (1997) for a popular description of the workshop, or ''The Very Early Universe'', ISBN 0-521-31677-4 eds Gibbons, Hawking & Siklos for a detailed report.</ref> He participated in one of four groups that calculated the fluctuations of [[inflation (cosmology)|cosmological inflation]].<ref>{{Cite journal|title=The development of irregularities in a single bubble inflationary universe|first=S.W.|last=Hawking|journal=Phys.Lett.|volume=B115|pages=295|year=1982|bibcode=1982PhLB..115..295H|doi=10.1016/0370-2693(82)90373-2|issue=4}}</ref> |

|accessdate=1 October 2009}}</ref> Hawking's inaugural lecture as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics was titled: "Is the end in sight for Theoretical Physics" and promoted the idea that [[supergravity]] would help solve many of the outstanding problems physicists were studying.{{sfn|Ferguson|2011|pp=93–94}} In 1982, Hawking participated in the three-week Nuffield Workshop on the Very Early Universe at Cambridge University.<ref>See Guth (1997) for a popular description of the workshop, or ''The Very Early Universe'', ISBN 0-521-31677-4 eds Gibbons, Hawking & Siklos for a detailed report.</ref> He participated in one of four groups that calculated the fluctuations of [[inflation (cosmology)|cosmological inflation]].<ref>{{Cite journal|title=The development of irregularities in a single bubble inflationary universe|first=S.W.|last=Hawking|journal=Phys.Lett.|volume=B115|pages=295|year=1982|bibcode=1982PhLB..115..295H|doi=10.1016/0370-2693(82)90373-2|issue=4}}</ref> |

||

In collaboration with [[James Hartle|Jim Hartle]], Hawking developed a model |

In collaboration with [[James Hartle|Jim Hartle]] in 1983, Hawking developed a model, known as the [[Hartle–Hawking state]], a proposal that, prior to the [[Planck epoch]], the [[universe]] had no boundary in space-time; essentially before the [[Big Bang]], time did not exist and the concept of the beginning of the universe is meaningless.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1103/PhysRevD.28.2960}}</ref> This replaced the initial singularity of the classical Big Bang models with a region akin to the North Pole. One cannot travel north of the North Pole, but there is no boundary there – it is simply the point where all north-running lines meet and end.{{sfn|Baird|2007|loc=p. 234}} While initially the no-boundary proposal predicted a [[Shape of the Universe|closed universe]], discussions with [[Neil Turok]] led to the realisation that it is also compatible with an open universe.{{sfn|Yulsman|2003|loc=pp. 174–176}} Later work by Hawking appeared to show that, if this no-boundary proposition were correct, then when the universe stopped expanding and eventually collapsed, time would run backwards.<!-- (Hawking famously used the example of broken teacups reassembling). -->{{sfn|Ferguson|2011|pp=180–182}} Work by one of his former students, [[Don Page (physicist)|Don Page]], led Hawking to withdraw this concept.{{sfn|Ferguson|2011|p=182}} |

||

Along with Thomas Hertog at the European Organization for Nuclear Research ([[CERN]]), in 2006 Hawking proposed a theory of "top-down cosmology", which says that the universe had no unique initial state and therefore that it is inappropriate to formulate a theory that predicts the universe's current configuration from one particular initial state.<ref>{{cite web |

Along with Thomas Hertog at the European Organization for Nuclear Research ([[CERN]]), in 2006 Hawking proposed a theory of "top-down cosmology", which says that the universe had no unique initial state and therefore that it is inappropriate to formulate a theory that predicts the universe's current configuration from one particular initial state.<ref>{{cite web |

||

Revision as of 01:01, 30 December 2012

Stephen Hawking | |

|---|---|

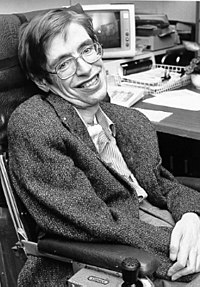

Stephen Hawking at NASA, 1980s | |

| Born | Stephen William Hawking 8 January 1942 Oxford, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouses |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Dennis Sciama |

| Other academic advisors | Robert Berman |

| Notable students | |

Stephen William Hawking, CH, CBE, FRS, FRSA (born 8 January 1942) is a British theoretical physicist, cosmologist, and author. Among his significant scientific works have been a collaboration with Roger Penrose on gravitational singularities theorems in the framework of general relativity, and the theoretical prediction that black holes emit radiation, often called Hawking radiation. Hawking was the first to set forth a cosmology explained by a union of the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. He is a vocal supporter of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

He is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. Hawking was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge between 1979 and 2009.

Hawking has achieved success with works of popular science in which he discusses his own theories and cosmology in general; his A Brief History of Time stayed on the British Sunday Times best-sellers list for a record-breaking 237 weeks. Hawking has a motor neurone disease related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a condition that has progressed over the years. He is almost entirely paralysed and communicates through a speech generating device. He married twice and has three children.

Early life and education

Stephen Hawking was born on 8 January 1942 to Frank and Isobel Hawking.[1][2] Despite family financial constraints, both parents had attended Oxford University, where Frank had studied medicine and Isobel Philosophy, Politics and Economics.[2] The two met shortly after the beginning of the Second World War at a medical research institute where Isobel was working as a secretary and Frank as a medical researcher.[2][3] Hawking's parents lived in Highgate but as London was under attack during the Second World War, his mother went to Oxford to give birth in greater safety.[4] He has two younger sisters, Philippa and Mary, and an adopted brother, Edward.[5] Hawking began his schooling at the Byron House School; he later blamed its "progressive methods" for his failure to learn to read while at the school.[6]

In 1950, when his father became head of the division of parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research, Hawking and his family moved to St Albans, Hertfordshire.[6][7] The eight-year-old Hawking attended St Albans High School for Girls for a few months; at that time, younger boys could attend one of the houses.[8][9] In St Albans, the family were considered highly intelligent and eccentric.[6][10] They lived a frugal existence in a large, cluttered, and poorly maintained house, and travelled in a converted London taxicab.[11][12] The family placed a high value on education, with regular trips to museums, and meals spent with everyone reading in silence.[6] During one of Hawking's father's frequent absences working in Africa,[13] the rest of the family spent four months in Majorca visiting his mother's friend Beryl and her husband, the poet Robert Graves.[8] On their return to England, Hawking attended Radlett School for a year[9] and from September 1952, St Albans School.[14] Hawking's father wanted his son to attend the well-regarded Westminster School, but 13-year-old Hawking was ill on the day of the scholarship examination. His family could not afford the school fees without the financial aid of a scholarship, so Hawking remained at St Albans.[15][16] As a positive consequence, Hawking remained with the close group of friends with whom he enjoyed board games, the manufacture of fireworks, model aeroplanes and boats,[17] and long discussions about Christianity and extrasensory perception.[18] From 1958, and with the help of the mathematics teacher Dikran Tahta, they built a computer from clock parts, an old telephone switchboard and other recycled components.[19][20]

Although at school he was known as "Einstein", Hawking was not initially successful academically.[21] With time, he began to show considerable aptitude for scientific subjects, and inspired by Tahta, decided to study mathematics at university.[22][23][24] Hawking's father advised him to study medicine, concerned that there were few jobs for mathematics graduates,[25] and wanted Hawking to attend University College, Oxford, his own alma mater. As it was not possible to read mathematics there at the time, Hawking decided to study physics and chemistry, and despite his headmaster's advice to wait till the next year, took the scholarship examinations in March 1959.[23][26] After performing well on the exams and interviews, University College accepted Hawking and offered him a scholarship.[26][27]

University studies

Hawking went up to Oxford in October 1959, at the age of 17.[28] For the first 18 months he was bored and lonely. He was younger than many other students, and he found the academic work "ridiculously easy".[29][30] His physics tutor, Robert Berman, later said "It was only necessary for him to know that something could be done, and he could do it without looking to see how other people did it."[31] A change occurred during his second and third year when, according to Berman, Hawking made more effort "to be one of the boys". He became popular as a lively and witty college member, interested in classical music and science fiction.[28] Part of the transformation resulted from his decision to join the college Boat Club, where he coxed a rowing team.[32][33] The rowing trainer at the time noted that Hawking cultivated a daredevil image, steering his crew on risky courses leading to damaged boats.[34][32]

Hawking has estimated that he had studied for only approximately 1000 hours during his three years at Oxford. These unimpressive study habits made sitting his Finals a challenge, and he decided only to answer questions on theoretical physics rather than those requiring factual knowledge. A first-class honours degree was a condition of acceptance for his plans for graduate study in cosmology at the University of Cambridge with Fred Hoyle.[35][36] Anxious, he slept poorly the night before the examinations and the final result was on the borderline between first and second class honours, making a viva necessary.[36][37] Hawking was concerned that he was considered a lazy and difficult student, and when asked at the oral examination to describe his future plans said "If you award me a First, I will go to Cambridge. If I receive a Second, I shall stay in Oxford, so I expect you will give me a First."[36][38] He was held in higher regard than he believed: as Berman commented, the examiners "were intelligent enough to realize they were talking to someone far cleverer than most of themselves".[36] After receiving a first-class BA (Hons.) degree, and following a trip to Iran with a friend, he began his graduate work at Trinity Hall, Cambridge in October 1962.[39][40]

Hawking's first year as a doctoral student was a difficult one. He was initially disappointed to find that he had been assigned Dennis William Sciama as a supervisor rather than Hoyle.[41][42] Hawking found his mathematical studies had been inadequate for his studies in general relativity and cosmology.[43] He was also struggling with his health. Hawking had noticed clumsiness during his final year at Oxford. He had fallen down the stairs and had difficulty rowing.[44][45] The problems worsened, and his speech became slightly slurred; his family noticed the issues when he returned to St. Albans for Christmas, and medical investigations were begun.[46][47] The diagnosis, of motor neuron disease, came when Hawking was 21, just after he had met Jane Wilde, who was to become his first wife; doctors gave him a life expectancy of two years.[48][49] Hawking fell into a depression, and though his doctors advised that he continue with his studies, he felt there was little point as he would not be able to complete it.[50] At the same time, however, his relationship with Jane, now an undergraduate in London, was slowly developing, and the couple were engaged in October 1964.[51][52] Hawking later said that the engagement "gave him something to live for."[53] Despite the disease's progression – Hawking had difficulty walking without support, and his speech was almost unintelligible — he returned to his work with enthusiasm and success.[54] Hawking began to develop a reputation for brilliance and brashness when he publicly challenged the work Fred Hoyle and his student Jayant Narlikar at a lecture in June 1964.[55][56] When Hawking began his graduate studies, there was much debate in the physics community about the prevailing theories of the creation of the universe: the Big Bang and the Steady State theories.[57] Inspired by Roger Penrose's black hole singularity theorem, Hawking applied the same thinking to the entire Universe, and during 1965 wrote up his thesis on this topic.[58] There were other positive developments that year: Hawking received a research fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, and he and Jane were married on July 14 1965.[59] He completed his doctorate in March 1966.[60]

Career

1966–75

Hawking and his Cambridge friend and colleague, Roger Penrose, calculated in 1970 that if the universe obeys the general theory of relativity and fits the models of physical cosmology developed by Alexander Friedmann, then it must have begun as a singularity.[61] This work demonstrated that, far from being mathematical curiosities which appear only in exceptional circumstances, singularities are a fairly common feature of general relativity.[62] Hawking's essay on this subject and an essay by Penrose shared the Adams prize in 1966.[63] Hawking's essay served as the basis for the book, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, that Hawking published with George Ellis in 1973.[64] The first years of marriage were hectic: Jane lived in London during the week as she completed her degree, and the couple had difficulty finding housing that was close enough to the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP) that Hawking, with his two sticks, could walk there. They travelled to the United States several times so Hawking could attend conferences. Jane began a PhD program, and a son, Robert, was born in May 1967.[65] In 1969, Hawking accepted a specially created 'Fellowship for Distinction in Science' to remain at Cambridge.[66] In the early 1970s, Hawking's work with Brandon Carter, Werner Israel and D. Robinson strongly supported John Wheeler's no-hair theorem – that any black hole can be fully described by the three properties of mass, angular momentum, and electric charge.[67] With James M. Bardeen and Carter, he proposed the four laws of black hole mechanics, drawing an analogy with thermodynamics.[68] In 1974, he calculated that black holes emit radiation, known today as Hawking radiation, until they exhaust their energy and evaporate.[69]

Hawking was elected one of the youngest Fellows of the Royal Society in 1974,[70] and in the same year he accepted the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Scholar visiting professorship at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) to work with his friend on the faculty, Kip Thorne.[71] As of 2011, he maintained ties to Caltech, having spent a month there almost every year since 1974.[72]

1975–present

The mid to late 1970s were a period of growing popularity and success for Hawking. His work was now much talked about; he was appearing in television documentaries, and in 1979 he became the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a position he held for 30 years until he retired in 2009.[73][74] Hawking's inaugural lecture as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics was titled: "Is the end in sight for Theoretical Physics" and promoted the idea that supergravity would help solve many of the outstanding problems physicists were studying.[75] In 1982, Hawking participated in the three-week Nuffield Workshop on the Very Early Universe at Cambridge University.[76] He participated in one of four groups that calculated the fluctuations of cosmological inflation.[77]

In collaboration with Jim Hartle in 1983, Hawking developed a model, known as the Hartle–Hawking state, a proposal that, prior to the Planck epoch, the universe had no boundary in space-time; essentially before the Big Bang, time did not exist and the concept of the beginning of the universe is meaningless.[78] This replaced the initial singularity of the classical Big Bang models with a region akin to the North Pole. One cannot travel north of the North Pole, but there is no boundary there – it is simply the point where all north-running lines meet and end.[79] While initially the no-boundary proposal predicted a closed universe, discussions with Neil Turok led to the realisation that it is also compatible with an open universe.[80] Later work by Hawking appeared to show that, if this no-boundary proposition were correct, then when the universe stopped expanding and eventually collapsed, time would run backwards.[81] Work by one of his former students, Don Page, led Hawking to withdraw this concept.[82]

Along with Thomas Hertog at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), in 2006 Hawking proposed a theory of "top-down cosmology", which says that the universe had no unique initial state and therefore that it is inappropriate to formulate a theory that predicts the universe's current configuration from one particular initial state.[83] Top-down cosmology posits that in some sense, the present "selects" the past from a superposition of many possible histories. In doing so, the theory suggests a possible resolution of the fine-tuning question.[84]

Thorne–Hawking–Preskill bet

In 1997, Hawking made a public scientific wager with Kip Thorne and John Preskill of Caltech concerning the black hole information paradox.[85] Thorne and Hawking argued that since general relativity made it impossible for black holes to radiate and lose information, the mass-energy and information carried by Hawking Radiation must be "new", and not from inside the black hole event horizon. Since this contradicted the quantum mechanics of microcausality, quantum mechanics would need to be rewritten. Preskill argued the opposite, that since quantum mechanics suggests that the information emitted by a black hole relates to information that fell in at an earlier time, the concept of black holes given by general relativity must be modified in some way.[86] The winner of the bet was to receive an encyclopedia of the loser's choice.[85]

In 2004, Hawking announced that he was conceding the bet because he now believed that black hole horizons should fluctuate and leak information, and gave Preskill a copy of Total Baseball. Comparing the useless information obtainable from a black hole to "burning an encyclopedia", Hawking commented, "I gave John an encyclopedia of baseball, but maybe I should just have given him the ashes".[85]

Personal life

Hawking married Jane Wilde in 1965. Jane cared for him until 1990 when the couple separated.[87] They had three children: Robert, Lucy, and Timothy.[87] Hawking married his personal care assistant, Elaine Mason, in 1995;[87] the couple divorced in October 2006.[88] In 1999, Jane Hawking published a memoir, Music to Move the Stars, describing her marriage to Hawking and its breakdown; in 2010 she published a revised version, Travelling to Infinity, My Life with Stephen.[89]

Illness

Hawking has a motor neurone disease related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a condition that has progressed over the years. As of 2012, he is almost completely paralysed and communicates through a speech generating device. Hawking's illness has advanced more slowly than typical cases of ALS: survival for more than 10 years after diagnosis is uncommon.[90][91]

Symptoms of the disease include increasing inability to control physical movements, including vocal functions, and severe coughing spells. In 1970, his difficulty in getting around made a wheelchair necessary.[92] From 1974 he could not feed himself or get out of bed, so graduate students helped, receiving free accommodation in return.[93] His speech became so slurred that he could be understood only by people who knew him well.[93] During a visit to CERN in Geneva in 1985, Hawking contracted pneumonia, which in his condition was life-threatening as it further restricted his already limited respiratory capacity. He had an emergency tracheotomy, losing what remained of his ability to speak.[94] A speech generating device was built in Cambridge, using software from an American company, that enables Hawking to operate a computer keyboard with small movements of his body, and then have a speech synthesiser speak the output.[95]

The speech synthesiser hardware he uses, DECtalk, which has an American accent, is no longer produced.[96] Asked why he has kept the same voice for so many years, Hawking stated that he has not heard a voice he likes better and that he identifies with it even though the synthesiser is both large and fragile by current standards.[97] For lectures and media appearances, Hawking prepares his remarks in advance,[failed verification] but when he answers questions, he and his system produce words at a rate of about one per minute.[98] Although Hawking's setup requires only a few characters to signal a complete word or phrase,[failed verification] because he can only enter data by twitching his cheek muscles, constructing complete sentences takes time.[98][99] Intel is working on a facial recognition system that will help speed up the writing.[100] The disease-related deterioration of his facial nerves continues such that there is a risk of him acquiring locked-in syndrome, so Hawking is collaborating with neuroscientists on a brain–computer interface that could translate Hawking's brain patterns into signals which would allow him to select letters and words.[99][100]

Hawking describes himself as lucky, as the slow progression of his disease has allowed him time to make influential discoveries and has not hindered him because, in his words, of "the help I have received from Jane, my children, and a large number of other people and organisations".[95]

Space and spaceflight

Hawking has suggested that space is the Earth's long term hope[101] and has indicated that he is almost certain that alien life exists in other parts of the universe: "To my mathematical brain, the numbers alone make thinking about aliens perfectly rational. The real challenge is to work out what aliens might actually be like".[102] He believes alien life not only exists on planets but perhaps in other places, like within stars or floating in outer space. He has also warned that a few of these species might be intelligent and threaten Earth:[103] "If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn't turn out well for the Native Americans".[102] He has advocated that, rather than try to establish contact, humans should try to avoid contact with alien life forms.[102]

In 2007, Hawking took a zero-gravity flight in a "Vomit Comet", courtesy of Zero Gravity Corporation, during which he experienced weightlessness eight times.[104] He was the first quadriplegic to float in zero gravity. Before the flight Hawking said:

"Many people have asked me why I am taking this flight. I am doing it for many reasons. First of all, I believe that life on Earth is at an ever-increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster such as sudden nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus, or other dangers. I think the human race has no future if it doesn't go into space. I therefore want to encourage public interest in space."[105]

Religious and philosophical views

In his early work, Hawking spoke of God in a metaphorical sense. In A Brief History of Time he wrote: "If we discover a complete theory, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason – for then we should know the mind of God."[106] In the same book he suggested the existence of God was unnecessary to explain the origin of the universe.[107] Hawking has stated that he is "not religious in the normal sense" and he believes that "the universe is governed by the laws of science. The laws may have been decreed by God, but God does not intervene to break the laws."[108] In an interview published in The Guardian, Hawking regarded the concept of Heaven as a myth, believing that there is "no heaven or afterlife" and that such a notion was a "fairy story for people afraid of the dark."[106][109]

At Google's Zeitgeist Conference in 2011, Hawking said that "philosophy is dead." He believes philosophers "have not kept up with modern developments in science" and that scientists "have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge." He said that philosophical problems can be answered by science, particularly new scientific theories which "lead us to a new and very different picture of the universe and our place in it".[110]

Recognition

On 19 December 2007, a statue of Hawking by artist Ian Walters was unveiled at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology, University of Cambridge.[111] Buildings named after Hawking include the Stephen W. Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador, El Salvador,[112] the Stephen Hawking Building in Cambridge,[113] and the Stephen Hawking Centre at Perimeter Institute in Canada.[114] In 2002, following a UK-wide vote, the BBC included him in their list of the 100 Greatest Britons.[115]

Awards and honours

Hawking has been awarded both the Eddington Medal (1975) and the Gold Medal (1985) from the British Royal Astronomical Society, and the Hughes (1976) and Copley (2006) Medals from the Royal Society.[87][116] In 1979 he received the Swiss Albert Einstein Medal[87] and he shared the Israeli Wolf Prize in Physics with Roger Penrose in 1988.[87] In 1981 he was awarded the American Franklin Medal, in 1999 the Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society,[117] and in 2003 the Michelson-Morley Award of Case Western Reserve University.[87] He was made a CBE in 1982 and a Companion of Honour in 1989.[87] In 2009 he received America's highest civilian honour, the Presidential Medal of Freedom,[118] He has also been awarded Spain's Fonseca Prize (2008)[119] and the Russian Fundamental Physics Prize (2012).[120]

Popular publications

Hawking's first popular science book, A Brief History of Time, was published on 1 April 1988[121] and stayed on the British Sunday Times best-sellers list for a record-breaking 237 weeks.[122] It was followed by The Universe in a Nutshell (2001). A collection of essays titled Black Holes and Baby Universes (1993) was also popular. He co-wrote A Briefer History of Time (2005) with Leonard Mlodinow to update his earlier works to make them accessible to a wider audience. In 2007 Hawking and his daughter, Lucy Hawking, published George's Secret Key to the Universe, a children's book focusing on science that Lucy Hawking described as "a bit like Harry Potter but without the magic."[123]

Books

- A Brief History of Time (1988)[124]

- Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays (1993)[125]

- The Universe in a Nutshell (2001)[124]

- On The Shoulders of Giants (2002)[124]

- A Briefer History of Time (2005)[124]

- God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History (2005)[124]

- The Grand Design (2010)[124]

Children's fiction

These are co-written with his daughter Lucy.

- George's Secret Key to the Universe (2007)[124]

- George's Cosmic Treasure Hunt (2009)[124]

- George and the Big Bang (2011)[124]

Films and series

- A Brief History of Time (1992)[126]

- Stephen Hawking's Universe (1997)[127][128]

- Horizon: The Hawking Paradox (2005)[129]

- Masters of Science Fiction (2007)[130]

- Stephen Hawking: Master of the Universe (2008)[131]

- Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking (2010)[132]

- Brave New World with Stephen Hawking (2011)[133]

- Stephen Hawking's Grand Design (2012)[134]

In popular culture

Hawking has appeared as himself on episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation,[135] The Simpsons,[136] Futurama,[137] and The Big Bang Theory.[138] His synthesiser voice was used on parts of the Pink Floyd song "Keep Talking".[139]

Hawking's early life and the onset of his illness was the subject of the 2004 BBC4 TV film Hawking in which he was portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch. In 2008, he was featured in the documentary series Stephen Hawking, Master of the Universe, for Channel 4. He presided over the unveiling of the "Chronophage" (time-eating) Corpus Clock at Corpus Christi College Cambridge in September of the same year.[140]

On 29 August 2012 he narrated the Enlightenment segment of the 2012 Summer Paralympics opening ceremony.[141]

See also

- Bekenstein–Hawking formula

- Black hole information paradox

- Gibbons–Hawking ansatz

- Gibbons–Hawking effect

- Gibbons–Hawking space

- Gibbons–Hawking–York boundary term

- Hartle–Hawking state

- The Black Hole War

References

- ^ Larsen 2005, pp. xiii, 2.

- ^ a b c Ferguson 2011, p. 21.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Larsen 2005, pp. 2, 5.

- ^ a b c d Ferguson 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Larsen 2005, p. 3.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, p. 24.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 11–12.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 13.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 8.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 25–26.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 26.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 25.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, p. 27.

- ^ Hoare, Geoffrey; Love, Eric (5 January 2007). "Dick Tahta". guardian.co.uk. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 41.

- ^ a b White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 28–29.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 46–47, 51.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 29.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Hawking 1992, p. 44.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 50.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Ferguson 2011, p. 31.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 54.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 54–55.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 33.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Donaldson, Gregg J. (May 1999). "The Man Behind the Scientist". Tapping Technology. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Larsen 2005, pp. 18–19.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 59–61.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. xiv.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 40.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 42.

- ^ White & Gribbin 2002, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 61–65.

- ^ Hawking, Stephen; Penrose, Roger (1970). "The Singularities of Gravitational Collapse and Cosmology". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 314 (1519): 529–548. Bibcode:1970RSPSA.314..529H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1970.0021.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. xix.

- ^ Hawking & Ellis 1973, p. xi.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 49.

- ^ Hawking & Israel 1989, p. 278.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 82.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 95.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 90–92.

- ^ "Hawking gives up academic title". BBC News. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 93–94.

- ^ See Guth (1997) for a popular description of the workshop, or The Very Early Universe, ISBN 0-521-31677-4 eds Gibbons, Hawking & Siklos for a detailed report.

- ^ Hawking, S.W. (1982). "The development of irregularities in a single bubble inflationary universe". Phys.Lett. B115 (4): 295. Bibcode:1982PhLB..115..295H. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(82)90373-2.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.28.2960, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.28.2960instead. - ^ Baird 2007, p. 234.

- ^ Yulsman 2003, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, pp. 180–182.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (26 June 2008). "Stephen Hawking's explosive new theory". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Hawking, S.W.; Hertog, T. (2006). "Populating the landscape: A top-down approach". Physical Review D. 73 (12). arXiv:hep-th/0602091. Bibcode:2006PhRvD..73l3527H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.123527.

- ^ a b c Hawking, S.W. (2005). "Information loss in black holes". Physical Review D. 72 (8). arXiv:hep-th/0507171. Bibcode:2005PhRvD..72h4013H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.72.084013.

- ^ Preskill, John. "John Preskill's comments about Stephen Hawking's concession". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Larsen 2005, pp. x–xix.

- ^ Sapsted, David (20 October 2006). "Hawking and second wife agree to divorce". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ "Welcome back to the family, Stephen". The Times. 6 May 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ Mitsumoto & Munsat 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Harmon, Katherine (7 January 2012). "How Has Stephen Hawking Lived to 70 with ALS?". Scientific American. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 32.

- ^ a b Stephen Hawking (1994). Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays. Random House. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-553-37411-7.

- ^ Larsen 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Hawking, Stephen. "Living with ALS". Stephen Hawking Official Website. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Greenemeier, Larry (10 August 2009). "Getting Back the Gift of Gab: Next-Gen Handheld Computers Allow the Mute to Converse". Scientific American. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking says pope told him not to study beginning of universe". USA Today. 15 June 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b de Lange, Catherine (30 December 2011). "The man who saves Stephen Hawking's voice". New Scientist. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b Boyle, Alan (25 June 2012). "How researchers hacked into Stephen Hawking's brain". NBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Start-up attempts to convert Prof Hawking's brainwaves into speech". BBC. 7 July 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (16 October 2001). "Colonies in space may be only hope, says Hawking". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ a b c "Stephen Hawking warns over making contact with aliens". BBC News. 25 April 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Hickman, Leo (25 April 2010). "Stephen Hawking takes a hard line on aliens". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Hawking takes zero-gravity flight". BBC News. 27 April 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Physicist Hawking experiences zero gravity". CNN. 26 April 2007. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ a b Sample, Ian (15 May 2011). "Stephen Hawking: 'There is no heaven; it's a fairy story'". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony (29 December 1991). "Towards a Theory of Everything". The Observer. p. 42.

Though A Brief History of Time brings in God as a useful metaphor, Hawking is an atheist

- ^ Stewart, Phil (31 October 2008). "Pope sees physicist Hawking at evolution gathering". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking: Heaven Is A Myth". The Huffington Post. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Warman, Matt (17 May 2011). "Stephen Hawking tells Google 'philosophy is dead'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Vice-Chancellor unveils Hawking statue". University of Cambridge. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ Komar, Oliver; Buechner, Linda (October 2000). "The Stephen W. Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador Central America Honours the Fortitude of a Great Living Scientist". Journal of College Science Teaching. XXX (2). Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "The Stephen Hawking Building". BBC News. 18 April 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Grand Opening of the Stephen Hawking Centre at Perimeter Institute". Perimeter Institute. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "100 great Britons – A complete list". Daily Mail. 21 August 2002. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Oldest, space-travelled, science prize awarded to Hawking". The Royal Society. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ "Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize". American Physical Society. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (13 August 2009). "Obama presents presidential medal of freedom to 16 recipients". guardian.co.uk. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Fonseca Prize 2008". University of Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ "Fundamental Physics Prize - News". Fundamental Physics Prize. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ Stephen Hawking (1 September 1998). A Brief History of Time: The Updated and Expanded Tenth Anniversary Edition. Random House Digital, Inc. p. viii. ISBN 978-0-553-38016-3.

- ^ Radford, Tim (31 July 2009). "How God propelled Stephen Hawking into the bestsellers lists". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Man must conquer other planets to survive, says Hawking". Daily Mail. 13 June 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Books". Stephen Hawking Official Website. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Black Holes and Baby Universes". Kirkus Reviews. 20 March 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "A Brief History of Time: Synopsis". Errol Morris. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking's Universe". PBS. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Kristine Larsen (30 June 2005). Stephen Hawking: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-313-32392-8. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "The Hawking Paradox". BBC. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ Richmond, Ray (3 August 2007). ""Masters of Science Fiction" too artistic for ABC". Reuters. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "Master of the Universe". Channel 4. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ "Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking". Discovery Channel. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Brave New World with Stephen Hawking". Channel 4. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking's Grand Design". Discovery Channel. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Okuda & Okuda 1999, p. 380.

- ^ Cheng, Maria (5 January 2012). "Stephen Hawking to turn 70, defying disease". Boston.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (3 January 2012). "Stephen Hawking: driven by a cosmic force of will - Telegraph". The Daily Telegraph. London: TMG. ISSN 0307-1235. OCLC 49632006. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "Professor Stephen Hawking films Big Bang Theory cameo". BBC news. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 94.

- ^ "Time to unveil Corpus Clock". Cambridgenetwork.co.uk. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ "Paralympics: Games opening promises 'journey of discovery'". BBC. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

Bibliography

- Baird, Eric (2007). Relativity in Curved Spacetime: Life Without Special Relativity. Chocolate Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-9557068-0-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ferguson, Kitty (2011). Stephen Hawking: His Life and Work. Transworld. ISBN 978-1-4481-1047-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gibbons, Gary W.; Hawking, Stephen W.; Siklos, S.T.C., eds. (1983). The Very early universe: proceedings of the Nuffield workshop, Cambridge, 21 June to 9 July, 1982. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31677-4.

- Hawking, Stephen W. (1994). Black holes and baby universes and other essays. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-37411-7.

- Hawking, Stephen W.; Ellis, George F.R. (1973). The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09906-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hawking, Stephen W. (1992). Stephen Hawking's A brief history of time: a reader's companion. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-07772-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hawking, Stephen W.; Israel, Werner (1989). Three Hundred Years of Gravitation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37976-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Larsen, Kristine (2005). Stephen Hawking: a biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32392-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitsumoto, Hiroshi; Munsat, Theodore L. (2001). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a guide for patients and families. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-888799-28-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Okuda, Michael; Okuda, Denise (1999). The Star trek encyclopedia: a reference guide to the future. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-53609-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Michael; Gribbin, John (2002). Stephen Hawking: A Life in Science (2nd ed.). National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-08410-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yulsman, Tom (2003). Origins: the quest for our cosmic roots. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7503-0765-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Boslough, John (1 June 1989). Stephen Hawking's universe: an introduction to the most remarkable scientist of our time. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-70763-8. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Pickover, Clifford A. (16 April 2008). Archimedes to Hawking: laws of science and the great minds behind them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533611-5. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

External links

- Stephen Hawking's web site

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Stephen Hawking at IMDb

- Stephen Hawking at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Template:Worldcat id

- Stephen Hawking collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Stephen Hawking collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- "Archival material relating to Stephen Hawking". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Stephen William Hawking at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Use dmy dates from November 2012

- 1942 births

- Academics of the University of Cambridge

- Adams Prize recipients

- Albert Einstein Medal recipients

- Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

- Alumni of University College, Oxford

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Cosmologists

- English astronomers

- English atheists

- English people with disabilities

- English physicists

- English science writers

- Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- People educated at St Albans School, Hertfordshire

- Honorary Fellows of University College, Oxford

- Living people

- Lucasian Professors of Mathematics

- Members of the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Mental calculators

- People educated at St Albans High School for Girls

- People from Oxford

- People from St Albans

- People with motor neurone disease

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Religious skeptics

- Stephen Hawking

- Theoretical physicists

- Wolf Prize in Physics laureates