Russian alphabet: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Listen |filename=russian_alphabet.ogg|title=Russian alphabet |description= Listen to the Russian alphabet | format =[[Ogg]]}} |

{{Listen |filename=russian_alphabet.ogg|title=Russian alphabet |description= Listen to the Russian alphabet | format =[[Ogg]]}} |

||

{{IPA notice}} |

{{IPA notice}} |

||

The '''Russian alphabet''' ({{lang-rus |русский алфавит}}, transliteration: ''rússkij alfavít'') is a form of the [[Cyrillic script]], developed in the [[First Bulgarian Empire]] during the 10th century AD at the [[Preslav Literary School]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters. |

The '''Russian alphabet''' ({{lang-rus |русский алфавит}}, transliteration: ''rússkij alfavít'') is a form of the [[Cyrillic script]], developed in the [[First Bulgarian Empire]] during the 10th century AD at the [[Preslav Literary School]].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters. |

||

==Alphabet== |

==Alphabet.== |

||

The Russian alphabet is as follows: |

The Russian alphabet is as follows: |

||

{| border=1 cellspacing=0 cellpadding=4 style="border-collapse:collapse; " |

{| border=1 cellspacing=0 cellpadding=4 style="border-collapse:collapse; " |

||

Revision as of 19:39, 22 April 2013

The Russian alphabet (Russian: русский алфавит, transliteration: rússkij alfavít) is a form of the Cyrillic script, developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 10th century AD at the Preslav Literary School.[citation needed] The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters.

Alphabet.

The Russian alphabet is as follows:

| Letter | Handwriting | Name | Old name | IPA | English example | № | Unicode (Hex) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Аа | а [a] |

азъ [as] |

/a/ | father | 1 | U+0410 / U+0430 | ||

| Бб | бэ [bɛ] |

буки [ˈbukʲɪ] |

/b/ or /bʲ/ | bad | – | U+0411 / U+0431 | ||

| Вв | вэ [vɛ] |

вѣди [ˈvʲedʲɪ] |

/v/ or /vʲ/ | vine | 2 | U+0412 / U+0432 | ||

| Гг | гэ [ɡɛ] |

глаголь [ɡlɐˈɡolʲ] |

/ɡ/ | go | 3 | U+0413 / U+0433 | ||

| Дд | дэ [dɛ] |

добро [dɐˈbro] |

/d/ or /dʲ/ | do | 4 | U+0414 / U+0434 | ||

| Ее | е [je] |

есть [jesʲtʲ] |

/je/ or / ʲe/ | yet | 5 | U+0415 / U+0435 | ||

| Ёё | ё [jo] |

– | /jo/ or / ʲo/ | yolk | – | U+0401 / U+0451 | ||

| Жж | жэ [ʐɛ] |

живѣте [ʐɨˈvʲetʲɪ][a] |

/ʐ/ | pleasure | – | U+0416 / U+0436 | ||

| Зз | зэ [zɛ] |

земля [zʲɪˈmlʲa] |

/z/ or /zʲ/ | zoo | 7 | U+0417 / U+0437 | ||

| Ии | и [i] |

иже [ˈiʐɨ] |

/i/ or / ʲi/ | me | 8 | U+0418 / U+0438 | ||

| Йй | и краткое [i ˈkratkəɪ] |

и съ краткой [ɪ s ˈkratkəj] |

/j/ | yes | – | U+0419 / U+0439 | ||

| Кк | ка [ka] |

како [ˈkakə] |

/k/ or /kʲ/ | kitten | 20 | U+041A / U+043A | ||

| Лл† | эл or эль [el] or [elʲ] |

люди [ˈlʲʉdʲɪ] |

/l/ or /lʲ/ | lamp | 30 | U+041B / U+043B | ||

| Мм | эм [ɛm] |

мыслѣте [mɨˈsʲlʲetʲɪ][2] |

/m/ or /mʲ/ | map | 40 | U+041C / U+043C | ||

| Нн | эн [ɛn] |

нашъ [naʂ] |

/n/ or /nʲ/ | not | 50 | U+041D / U+043D | ||

| Оо | о [о] |

онъ [on] |

/o/ | more | 70 | U+041E / U+043E | ||

| Пп | пэ [pɛ] |

покой [pɐˈkoj] |

/p/ or /pʲ/ | spell | 80 | U+041F / U+043F | ||

| Рр | эр [ɛr] |

рцы [rtsɨ] |

/r/ or /rʲ/ | rolled r | 100 | U+0420 / U+0440 | ||

| Сс | эс [ɛs] |

слово [ˈslovə] |

/s/ or /sʲ/ | see | 200 | U+0421 / U+0441 | ||

| Тт | тэ [tɛ] |

твердо [ˈtvʲɛrdə] |

/t/ or /tʲ/ | stool | 300 | U+0422 / U+0442 | ||

| Уу | у [u] |

укъ [uk] |

/u/ | boot | 400 | U+0423 / U+0443 | ||

| Фф | эф [ɛf] |

фертъ [fʲɛrt] |

/f/ or /fʲ/ | face | 500 | U+0424 / U+0444 | ||

| Хх | ха [xa] |

хѣръ [xʲɛr] |

/x/ | loch | 600 | U+0425 / U+0445 | ||

| Цц | це [tsɛ] |

цы [t͡sɨ] |

/t͡s/ | sits | 900 | U+0426 / U+0446 | ||

| Чч | че [tɕe] |

червь [t͡ɕɛrfʲ] |

/t͡ɕ/ | chip | 90 | U+0427 / U+0447 | ||

| Шш | ша [ʂa] |

ша [ʂa] |

/ʂ/ | Close to sharp (voiceless retroflex fricative) | – | U+0428 / U+0448 | ||

| Щщ | ща [ɕɕa] |

ща [ɕt͡ɕa] |

/ɕɕ/ | sheer (sometimes instead pronounced as with fresh cheese) (a voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative) | – | U+0429 / U+0449 | ||

| Ъъ | твёрдый знак [ˈtvʲordɨj znak] |

еръ [jer] |

silent, prevents palatalization of the preceding consonant | – | U+042A / U+044A | |||

| Ыы | ы [ɨ] |

еры [jɪˈrɨ] |

[ɨ] | roses or silly (close central unrounded vowel) | – | U+042B / U+044B | ||

| Ьь | мягкий знак [ˈmʲæxʲkʲɪj znak] |

ерь [jerʲ] |

/ ʲ/ | silent, slightly palatalizes the preceding consonant (if it is phonologically possible) | – | U+042C / U+044C | ||

| Ээ | э [ɛ] |

э оборотное [ˈɛ əbɐˈrotnəɪ] |

/ɛ/ | met | – | U+042D / U+044D | ||

| Юю | ю [ju] |

ю [ju] |

/ju/ or / ʲu/ | use | – | U+042E / U+044E | ||

| Яя | я [ja] |

я [ja] |

/ja/ or / ʲa/ | yard | – | U+042F / U+044F | ||

| letters eliminated in 1917–18 | ||||||||

| Іі | – | – | і десятеричное [i] |

/i/ or / ʲi/ or /j/ | Like и or й | 10 | ||

| Ѳѳ | – | – | ѳита [fʲɪˈta] |

/f/ or /fʲ/ | Like ф | 9 | ||

| Ѣѣ | – | – | ять [jætʲ] |

/e/ or / ʲe/ | Like е | – | ||

| Ѵѵ | – | – | ижица [ˈiʐɨtsə] |

/i/ or / ʲi/ | Usually like и, see below | – | ||

| letters eliminated before 1750 | ||||||||

| Ѕѕ | – | – | зѣло [zʲɪˈlo][3] |

/z/ or /zʲ/ | Like з | 6 | ||

| Ѯѯ | – | – | кси [ksʲi] |

/ks/ or /ksʲ/ | Like кс | 60 | ||

| Ѱѱ | – | – | пси [psʲi] |

/ps/ or /psʲ/ | Like пс | 700 | ||

| Ѡѡ | – | – | омега [ɐˈmʲeɡə] |

/o/ | Like о | 800 | ||

| Ѫѫ | – | – | юсъ большой [jus bɐlʲˈʂoj] |

/u/, /ju/ or / ʲu/ | Like у or ю | – | ||

| Ѧѧ | – | – | юсъ малый [jus ˈmɑlɨj] |

/ja/ or / ʲa/ | Like я | – | ||

| Ѭѭ | – | – | юсъ большой іотированный [jus bɐlʲˈʂoj jɪˈtʲirəvənnɨj] |

/ju/ or / ʲu/ | Like ю | – | ||

| Ѩѩ | – | – | юсъ малый іотированный [jus ˈmɑlɨj jɪˈtʲirəvən.nɨj] |

/ja/ or / ʲa/ | Like я | – | ||

The consonant letters represent both as "soft" (palatalized, represented in the IPA with a ⟨ʲ⟩) and "hard" consonant phonemes. If a consonant letter is followed by a vowel letter, then the soft/hard quality of the consonant depends on whether the vowel is meant to follow "hard" consonants ⟨а, о, э, у, ы⟩ or "soft" ones ⟨я, ё, е, ю, и⟩; see below. A handful of consonant phonemes do not have phonemically distinct "soft" and "hard" variants. See Russian phonology for details.

Letter names

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Until approximately 1900, mnemonic names inherited from Church Slavonic were used for the letters. They are given here in the pre-1918 orthography of the post-1708 civil alphabet.

The great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin wrote: "The letters constituting the Slavonic alphabet do not produce any sense. Аз, буки, веди, глаголь, добро etc. are separate words, chosen just for their initial sound". But since the names of the first letters of the Slavonic alphabet seem to form text, attempts were made to compose sensible text from all letters of the alphabet.

Here is one such attempt to "decode" the message:

| аз буки веди | I know letters |

| глаголь добро есть | "To speak is a beneficence" or "The word is property" |

| живете зело, земля, и иже и како люди | "Live, while working heartily, people of the Earth, in the manner people should obey" |

| мыслете наш он покой | "try to understand the Universe (the world that is around)" |

| рцы слово твердо | "carry the knowledge ("word" here refers to "knowledge") firmly" |

| ук ферт хер | "The knowledge is fertilized by the Creator, knowledge is the gift of God" |

| цы червь ша ер ять ю | "Try harder, to understand the Light of the Creator" |

In this attempt words only in two first lines somewhat correspond to real meanings of the letters' names, while "translations" in other lines seem to be fabrications or fantasies. For example, "покой" ("rest" or "apartment") doesn't mean "the Universe", and "ферт" doesn't have any meaning in Russian or other Slavonic languages (there are no words of Slavonic origin beginning with "f" at all). The last line contains only one translatable word – "червь" ("worm"), which, however, was not included in the "translation".

Another version of "the message", incorporating the letters phased out by mid-1750s, reads:

| Verse | Transliteration | Translation |

| "А(в)се буквы ведая глаголить – добро есть. Живет зло (на) земле вечно и каждому людину мыслить надо о покаянии, речью (и) словом твердить учение веры Христовой (в) Царствие Божие, чаще шептать, щтоб (все буквы) (вз)ятием этим усвоить и по законам божьим стремиться писать слова и жить" | A(v)sye bukvy vyedaya glagolit' – dobro yest'. Zhivyet zlo (na) zyemlye vyechno i kazhdomu lyudinu myslit' nado o pokayaniyi, ryech'yu (i) slovom tverdit' uchyeniye vyery Khristovoy (v) Tsarstviye Bozhiye, chashchye sheptat', shchtob (vsye bukvy) (vz)yatiyem etim usvoyit' i po zakonam bozh'im stremit'sya pisat' slova i zhit') | "Knowing all these letters renders speech a virtue. Evil lives on Earth eternally, and each person must think of repentance, with speech and word making firm in their mind the faith in Christ and the Kingdom of God. Whisper [the letters] frequently to make them yours by this repetition in order to write and live according to laws of God". |

Non-vocalized letters

- hard sign (⟨ъ⟩), when put after a consonant, acts like a "silent back vowel" that separates a succeeding iotated vowel from the consonant, making that sound with a distinct /j/ glide. Today it is used mostly to separate a prefix from the following root. Its original pronunciation, lost by 1400 at the latest, was that of a very short middle schwa-like sound, /ŭ/ but likely pronounced [ə] or [ɯ]

- soft sign (⟨ь⟩) acts like a "silent front vowel" and indicates that the preceding consonant is palatalized. This is important as palatalization is phonemic in Russian. For example, брат [brat] ('brother') contrasts with брать [bratʲ] ('to take'). The original pronunciation of the soft sign, lost by 1400 at the latest, was that of a very short fronted reduced vowel /ĭ/ but likely pronounced [ɪ] or [jɪ]. There are still some remains of this ancient reading in modern Russian, in the co-existing versions of the same name, read differently, such as in Марья and Мария (Mary).

Vowels

The vowels ⟨е, ё, и, ю, я⟩ indicate a preceding palatal consonant and with the exception of ⟨и⟩ are iotated (pronounced with a preceding /j/) when written at the beginning of a word or following another vowel (initial ⟨и⟩ was iotated until the nineteenth century). The IPA vowels shown are a guideline only and sometimes are realized as different sounds, particularly when unstressed. However, ⟨е⟩ is used in words of foreign origin without palatalization and indicate /e/. Which words this applies to must be learned (generally to avoid using ⟨э⟩ after a consonant), and ⟨я⟩ is often realized as [æ] between soft consonants, such as in мяч ("toy ball").

⟨ы⟩ is an old Common Slavonic tense intermediate vowel, thought to have been preserved better in modern Russian than in other Slavic languages. It was originally nasalized in certain positions: камы [ˈka.mɨ̃]; камень [ˈka.mʲɪnʲ] ("rock"). Its written form developed as follows: ⟨ъ⟩ + ⟨і⟩ → ⟨ъı⟩ → ⟨ы⟩.

⟨э⟩ was introduced in 1708 to distinguish the non-iotated/non-palatalizing /e/ from the iotated/palatalizing one. The original usage had been ⟨е⟩ for the uniotated /e/, ⟨ѥ⟩ or ⟨ѣ⟩ for the iotated, but ⟨ѥ⟩ had dropped out of use by the sixteenth century. In native Russian words, ⟨э⟩ is found only at the beginnings of words, but otherwise it may be found elsewhere, such as when spelling out English or other foreign names, or in words of foreign origin such as the brand-name Aeroflot (Аэрофлот).

⟨ё⟩, introduced by Karamzin in 1797 and made official in 1943 by the Soviet Ministry of Education,[4] marks a /jo/ sound that has historically developed from /je/ under stress, a process that continues today. The letter ⟨ё⟩ is optional (in writing, not in pronunciation): it is formally correct to write ⟨e⟩ for both /je/ and /jo/. None of the several attempts in the twentieth century to mandate the use of ⟨ё⟩ have stuck.

| Grapheme | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| і | Decimal I | identical in pronunciation to ⟨и⟩, was used exclusively immediately in front of other vowels and the ⟨й⟩ ("Short I") (for example, ⟨патріархъ⟩ [pətrʲɪˈarx], 'patriarch') and in the word ⟨міръ⟩ [mʲir] ('world') and its derivatives, to distinguish it from the word ⟨миръ⟩ [mʲir] ('peace') (the two words are actually etymologically cognate[5][6] and not arbitrarily homonyms).[7] |

| ѳ | Fita | from the Greek theta, was identical to ⟨ф⟩ in pronunciation, but was used etymologically (for example, ⟨Ѳёдор⟩ "Theodore"). |

| ѣ | Yat | originally had a distinct sound, but by the middle of the eighteenth century had become identical in pronunciation to ⟨е⟩ in the standard language. Since its elimination in 1918, it has remained a political symbol of the old orthography. |

| ѵ | Izhitsa | from the Greek upsilon, usually identical to ⟨и⟩ in pronunciation, as in Byzantine Greek, was used etymologically for Greek loanwords; by 1918, it had become very rare. In spellings of the eighteenth century, it was also used after some vowels that have since been replaced with ⟨в⟩. For example, a Greek prefix originally spelled ⟨аѵто⟩ is now spelled ⟨авто⟩. |

Letters in disuse by 1750

⟨ѯ⟩ and ⟨ѱ⟩ derived from Greek letters xi and psi, used etymologically though inconsistently in secular writing until the eighteenth century, and more consistently to the present day in Church Slavonic.

⟨ѡ⟩ is the Greek letter omega, identical in pronunciation to ⟨о⟩, used in secular writing until the eighteenth century, but to the present day in Church Slavonic, mostly to distinguish inflexional forms otherwise written identically.

⟨ѕ⟩ corresponded to a more archaic /dz/ pronunciation, already absent in East Slavic at the start of the historical period, but kept by tradition in certain words until the eighteenth century in secular writing, and in Church Slavonic to the present day.

The yuses ⟨ѫ⟩ and ⟨ѧ⟩, letters that originally used to stand for nasalized vowels /õ/ and /ẽ/, had become, according to linguistic reconstruction, irrelevant for East Slavic phonology already at the beginning of the historical period, but were introduced along with the rest of the Cyrillic script. The letters ⟨ѭ⟩ and ⟨ѩ⟩ had largely vanished by the twelfth century. The uniotated ⟨ѫ⟩ continued to be used, etymologically, until the sixteenth century. Thereafter it was restricted to being a dominical letter in the Paschal tables. The seventeenth-century usage of ⟨ѫ⟩ and ⟨ѧ⟩ (see next note) survives in contemporary Church Slavonic.

The letter ⟨ѧ⟩ was adapted to represent the iotated /ja/ ⟨я⟩ in the middle or end of a word; the modern letter ⟨я⟩ is an adaptation of its cursive form of the seventeenth century, enshrined by the typographical reform of 1708.

Until 1708, the iotated /ja/ was written ⟨ıa⟩ at the beginning of a word. This distinction between ⟨ѧ⟩ and ⟨ıa⟩ survives in Church Slavonic.

Although it is usually stated that the letters labelled "fallen into disuse by the eighteenth century" in the table above were eliminated in the typographical reform of 1708, reality is somewhat more complex. The letters were indeed originally omitted from the sample alphabet, printed in a western-style serif font, presented in Peter's edict, along with the modern letter ⟨й⟩, but were reinstated under pressure from the Russian Orthodox Church in a later variant of the modern typeface. Nonetheless, they fell completely out of use in secular writing by 1750.

Treatment of foreign sounds

Because Russian borrows terms from other languages, there are various conventions in dealing with sounds not present in Russian. For example, while Russian has no [h], there are a number of common words (particularly proper nouns) borrowed from languages like English and German that contain such a sound in the original language. In well-established terms, such as галлюцинация [gəlʲutsɨˈnatsɨjə] ('hallucination'), this is written with ⟨г⟩ and pronounced with /g/ while newer terms use ⟨х⟩, pronounced with /x/, such as хобби [ˈxobʲɪ] ('hobby').[8]

Similarly, words originally with [θ] in their source language are either pronounced with /t(ʲ)/), as in the name Тельма ('Thelma') or, if borrowed early enough, with /f(ʲ)/ or /v(ʲ)/, as in the names Фёдор ('Theodore') and Матве́й ('Matthew').

There are also certain tendencies in borrowed words. For example, in loanwords from French and German, palatal and velar consonants tend to be soft before /u/ so that, for example, Küchelbecker becomes Кюхельбе́кер [kʲʉxʲɪlˈbɛkʲɛr].[9]

Numeric values

The numerical values correspond to the Greek numerals, with ⟨ѕ⟩ being used for digamma, ⟨ч⟩ for koppa, and ⟨ц⟩ for sampi. The system was abandoned for secular purposes in 1708, after a transitional period of a century or so; it continues to be used in Church Slavonic.

Diacritics

Russian spelling uses fewer diacritics than those used for most European languages. The only diacritic, in the proper sense, is the acute accent ⟨◌́⟩ (Russian: знак ударения 'mark of stress'), which marks stress on a vowel, as it is done in Spanish. Although Russian word stress is often unpredictable and can fall on different syllables in different forms of the same word, this diacritic is only used in special cases: in dictionaries, children's books, or language-learning resources, on minimal pairs distinguished only by stress (for instance, за́мок 'castle' vs. замо́к 'lock'). Rarely, it is used to specify the stress in uncommon foreign words and in poems where unusual stress is used to fit the meter.

The letter ⟨ё⟩ is a special variant of the letter ⟨е⟩, which is not always distinguished in written Russian, but the umlaut-like sign has no other uses. Stress on this letter is never marked, as it is always stressed, except in some loanwords.

Unlike the case of ⟨ё⟩, the letter ⟨й⟩ has completely separated from ⟨и⟩. It is neither considered a vowel, nor even a diacriticized letter.

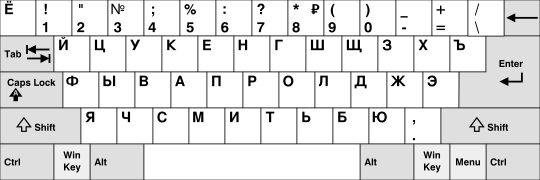

Keyboard layout

The Russian keyboard layout for PC computers is as follows:

See also

- Russian cursive (handwritten letters)

- Russian orthography

- Reforms of Russian orthography

- Russian braille

- Russian manual alphabet

- Romanization of Russian

- Computer russification

- Russian phonology

- Cyrillic script

- Yoficator

Notes

- ^ Ushakov, Dmitry, "живете", Толковый словарь русского языка Ушакова (article) (in Russian), RU: Yandex

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help); the dictionary makes difference between е and ё.[1]

References

- ^ Ushakov, Dmitry, "ёлка", Толковый словарь русского языка Ушакова (in Russian), RU: Yandex.

- ^ Ushakov, Dmitry, "мыслете", Толковый словарь русского языка Ушакова (article) (in Russian), RU: Yandex

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help). - ^ ФЭБ, RU: Feb web.

- ^ Benson 1960, p. 271.

- ^ Vasmer 1979.

- ^ Vasmer, "мир", Dictionary (etymology) (in Russian) (online ed.), retrieved 16 October 2005.

- ^ Smirnovskiy 1915, p. 4.

- ^ Dunn & Khairov 2009, pp. 17–8.

- ^ Halle 1959, p. 73.

Bibliography

- Benson, Morton (1960), "Review of The Russian Alphabet by Thomas F. Magner", The Slavic and East European Journal, 4 (3): 271–72

- Dunn, John; Khairov, Shamil (2009), Modern Russian Grammar, Modern Grammars, Routledge

- Halle, Morris (1959), Sound Pattern of Russian, MIT Press

- Smirnovskiy, P (1915), A Textbook in Russian Grammar, vol. Part I. Etymology (26th ed.), CA: Shaw

- Vasmer, Max (1979), Russian Etymological Dictionary, Winter

External links

- Cyrillic Virtual Keyboard (Cyrillic Fonts) with Russian Spellcheck (product), Soft corp.

- CyrAcademisator, Podolak. Bi-directional online transliteration for ALA-LC (diacritics), scientific, ISO/R 9, ISO 9, GOST 7.79B and others. Supports Old Slavonic characters

- Petherick, David, "How to Read the Russian Alphabet in 75 Minutes", Knol, Google.

- "Russian alphabet audio slowly and at normal speed. Five letters at a time", Learn Russian, Language 101

- Learn Russian Alphabet (Videos), Wiki translate.

- Sounds of individual letters of Russian Alphabet, Russian for everyone.

- How to read Russian (with audio) (course with audio and reading exercises), Russian for free.