Windmill: Difference between revisions

Replaced lossy JPEG with lossless PNG. |

m →Spread and decline: "the" to "there" |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

[[File:3 windmills.JPG||thumb|Oilmill [[De Zoeker, Zaandam|De Zoeker]], paintmill [[De Kat, Zaandam|De Kat]] and [[Paltrok mill|paltrok]] sawmill [[De Gekroonde Poelenburg, Zaandam|De Gekroonde Poelenburg]] at the [[Zaanse Schans]]]] |

[[File:3 windmills.JPG||thumb|Oilmill [[De Zoeker, Zaandam|De Zoeker]], paintmill [[De Kat, Zaandam|De Kat]] and [[Paltrok mill|paltrok]] sawmill [[De Gekroonde Poelenburg, Zaandam|De Gekroonde Poelenburg]] at the [[Zaanse Schans]]]] |

||

The total number of wind-powered mills in Europe is estimated to have been around 200,000 at its peak, which is modest compared to some 500,000 waterwheels.<ref name="lowtechmag">{{cite web|url=http://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2009/10/history-of-industrial-windmills.html |title=Wind powered factories: history (and future) of industrial windmills |publisher=Low-tech Magazine |date=2009-10-08 |accessdate=2013-08-15}}</ref> Windmills were applied in regions where |

The total number of wind-powered mills in Europe is estimated to have been around 200,000 at its peak, which is modest compared to some 500,000 waterwheels.<ref name="lowtechmag">{{cite web|url=http://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2009/10/history-of-industrial-windmills.html |title=Wind powered factories: history (and future) of industrial windmills |publisher=Low-tech Magazine |date=2009-10-08 |accessdate=2013-08-15}}</ref> Windmills were applied in regions where there was too little water, where rivers freeze in winter and in flat lands where the flow of the river was too slow to provide the required power.<ref name="lowtechmag"/> With the coming of the [[industrial revolution]], the importance of wind and water as primary industrial energy sources declined and were eventually replaced by steam (in [[steam mill]]s) and [[internal combustion]] engines, although windmills continued to be built in large numbers until late in the nineteenth century. |

||

More recently, windmills have been preserved for their historic value, in some cases as static exhibits when the antique machinery is too fragile to put in motion, and in other cases as fully working mills.<ref name="Victorian Farm">''Victorian Farm'', Episode 1. Directed and produced by Naomi Benson. BBC Television</ref> |

More recently, windmills have been preserved for their historic value, in some cases as static exhibits when the antique machinery is too fragile to put in motion, and in other cases as fully working mills.<ref name="Victorian Farm">''Victorian Farm'', Episode 1. Directed and produced by Naomi Benson. BBC Television</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:12, 18 April 2014

A windmill is a machine that converts the energy of wind into rotational energy by means of vanes called sails or blades.[1][2] The reason for the name "windmill" is that the devices originally were developed for milling grain for food production; the name stuck when in the course of history, windmill machinery was adapted to supply power for many industrial and agricultural needs other than milling.[3] The majority of modern windmills take the form of wind turbines used to generate electricity, or windpumps used to pump water, either for land drainage or to extract groundwater.

Windmills in antiquity

The windwheel of the Greek engineer Heron of Alexandria in the first century AD is the earliest known instance of using a wind-driven wheel to power a machine.[4][5] Another early example of a wind-driven wheel was the prayer wheel, which was used in ancient Tibet and China since the fourth century.[6] It has been claimed that the Babylonian emperor Hammurabi planned to use wind power for his ambitious irrigation project in the seventeenth century BC.[7]

Horizontal windmills

The first practical windmills had sails that rotated in a horizontal plane, around a vertical axis.[8] According to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, these panemone windmills were invented in eastern Persia as recorded by the Persian geographer Estakhri in the ninth century.[9][10] The authenticity of an earlier anecdote of a windmill involving the second caliph Umar (AD 634–644) is questioned on the grounds that it appears in a tenth-century document.[11] Made of six to 12 sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind grain or draw up water, and were quite different from the later European vertical windmills. Windmills were in widespread use across the Middle East and Central Asia, and later spread to China and India from there.[12]

A similar type of horizontal windmill with rectangular blades, used for irrigation, can also be found in thirteenth-century China (during the Jurchen Jin Dynasty in the north), introduced by the travels of Yelü Chucai to Turkestan in 1219.[13]

Horizontal windmills were built, in small numbers, in Europe during the 18th and nineteenth centuries,[8] for example Fowler's Mill at Battersea in London, and Hooper's Mill at Margate in Kent. These early modern examples seem not to have been directly influenced by the horizontal windmills of the Middle and Far East, but to have been independent inventions by engineers influenced by the Industrial Revolution.[14]

Vertical windmills

Due to a lack of evidence, debate occurs among historians as to whether or not Middle Eastern horizontal windmills triggered the original development of European windmills.[15][16][17][18] In northwestern Europe, the horizontal-axis or vertical windmill (so called due to the plane of the movement of its sails) is believed to date from the last quarter of the twelfth century in the triangle of northern France, eastern England and Flanders.

The earliest certain reference to a windmill in Europe (assumed to have been of the vertical type) dates from 1185, in the former village of Weedley in Yorkshire which was located at the southern tip of the Wold overlooking the Humber estuary.[19] A number of earlier, but less certainly dated, twelfth-century European sources referring to windmills have also been found.[20] These earliest mills were used to grind cereals.

Post mill

The evidence at present is that the earliest type of European windmill was the post mill, so named because of the large upright post on which the mill's main structure (the "body" or "buck") is balanced. By mounting the body this way, the mill is able to rotate to face the wind direction; an essential requirement for windmills to operate economically in north-western Europe, where wind directions are variable. The body contains all the milling machinery. The first post mills were of the sunken type, where the post was buried in an earth mound to support it. Later, a wooden support was developed called the trestle. This was often covered over or surrounded by a roundhouse to protect the trestle from the weather and to provide storage space. This type of windmill was the most common in Europe until the nineteenth century, when more powerful tower and smock mills replaced them.

Hollow-post mill

In a hollow-post mill, the post on which the body is mounted is hollowed out, to accommodate the drive shaft.[21] This makes it possible to drive machinery below or outside the body while still being able to rotate the body into the wind. Hollow-post mills driving scoop wheels were used in the Netherlands to drain wetlands from the fourteenth century onwards.

Tower mill

By the end of the thirteenth century, the masonry tower mill, on which only the cap is rotated rather than the whole body of the mill, had been introduced. The spread of tower mills came with a growing economy that called for larger and more stable sources of power, though they were more expensive to build. In contrast to the post mill, only the cap of the tower mill needs to be turned into the wind, so the main structure can be made much taller, allowing the sails to be made longer, which enables them to provide useful work even in low winds. The cap can be turned into the wind either by winches or gearing inside the cap or from a winch on the tail pole outside the mill. A method of keeping the cap and sails into the wind automatically is by using a fantail, a small windmill mounted at right angles to the sails, at the rear of the windmill. These are also fitted to tail poles of post mills and are common in Great Britain and English-speaking countries of the former British Empire, Denmark, and Germany but rare in other places. Around some parts of the Mediterranean Sea, tower mills with fixed caps were built because the wind's direction varied little most of the time.

Smock mill

The smock mill is a later development of the tower mill, where the tower is replaced by a wooden framework, called the "smock." The smock is commonly of octagonal plan, though examples with more, or fewer, sides exist. The smock is thatched, boarded or covered by other materials, such as slate, sheet metal, or tar paper. The lighter construction in comparison to tower mills make smock mills practical as drainage mills as these often had to be built in areas with unstable subsoil. Having originated as a drainage mill, smock mills are also used for a variety of purposes. When used in a built-up area it is often placed on a masonry base to raise it above the surrounding buildings.

Mechanics

Sails

Common sails consist of a lattice framework on which a sailcloth is spread. The miller can adjust the amount of cloth spread according to the amount of wind available and power needed. In medieval mills, the sailcloth was wound in and out of a ladder type arrangement of sails. Postmedieval mill sails had a lattice framework over which the sailcloth was spread, while in colder climates, the cloth was replaced by wooden slats, which were easier to handle in freezing conditions.[22] The jib sail is commonly found in Mediterranean countries, and consists of a simple triangle of cloth wound round a spar.

In all cases, the mill needs to be stopped to adjust the sails. Inventions in Great Britain in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to sails that automatically adjust to the wind speed without the need for the miller to intervene, culminating in patent sails invented by William Cubitt in 1813. In these sails, the cloth is replaced by a mechanism of connected shutters.

In France, Pierre-Théophile Berton invented a system consisting of longitudinal wooden slats connected by a mechanism that lets the miller open them while the mill is turning. In the twentieth century, increased knowledge of aerodynamics from the development of the airplane led to further improvements in efficiency by German engineer Bilau and several Dutch millwrights.

The majority of windmills have four sails. Multiple-sailed mills, with five, six or eight sails, were built in Great Britain (especially in and around the counties of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire), Germany, and less commonly elsewhere. Earlier multiple-sailed mills are found in Spain, Portugal, Greece, parts of Romania, Bulgaria, and Russia.[23] A mill with an even number of sails has the advantage of being able to run with a damaged sail and the one opposite removed without resulting in an unbalanced mill.

Machinery

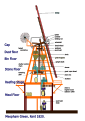

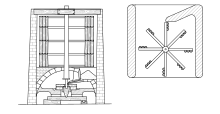

Gears inside a windmill convey power from the rotary motion of the sails to a mechanical device. The sails are carried on the horizontal windshaft. Windshafts can be wholly made of wood, or wood with a cast iron poll end (where the sails are mounted) or entirely of cast iron. The brake wheel is fitted onto the windshaft between the front and rear bearing. It has the brake around the outside of the rim and teeth in the side of the rim which drive the horizontal gearwheel called wallower on the top end of the vertical upright shaft. In grist mills, the great spur wheel, lower down the upright shaft, drives one or more stone nuts on the shafts driving each millstone. Post mills sometimes have a head and/or tail wheel driving the stone nuts directly, instead of the spur gear arrangement. Additional gear wheels drive a sack hoist or other machinery. The machinery differs if the windmill is used for other applications than milling grain. A drainage mill uses another set of gear wheels on the bottom end of the upright shaft to drive a scoop wheel or Archimedes' screw. Sawmills use a crankshaft to provide a reciprocating motion to the saws. Windmills have been used to power many other industrial processes, including papermills, threshing mills, and to process oil seeds, wool, paints and stone products.[3]

-

An isometric drawing of the machinery of the Beebe Windmill

-

Cross section of a post mill

-

Windshaft, brake wheel, and brake blocks in smock mill d'Admiraal in Amsterdam

-

Interior view, Pantigo windmill, East Hampton, New York Historic American Buildings Survey

-

Technical drawing of a 1793 Dutch tower mill for land drainage

Spread and decline

The total number of wind-powered mills in Europe is estimated to have been around 200,000 at its peak, which is modest compared to some 500,000 waterwheels.[22] Windmills were applied in regions where there was too little water, where rivers freeze in winter and in flat lands where the flow of the river was too slow to provide the required power.[22] With the coming of the industrial revolution, the importance of wind and water as primary industrial energy sources declined and were eventually replaced by steam (in steam mills) and internal combustion engines, although windmills continued to be built in large numbers until late in the nineteenth century. More recently, windmills have been preserved for their historic value, in some cases as static exhibits when the antique machinery is too fragile to put in motion, and in other cases as fully working mills.[24]

Of the 10,000 windmills in use in the Netherlands around 1850,[25] about 1000 are still standing. Most of these are being run by volunteers, though some grist mills are still operating commercially. Many of the drainage mills have been appointed as backup to the modern pumping stations. The Zaan district has been said to have been the first industrialized region of the world with around 600 operating wind-powered industries by the end of the eighteenth century.[25] Economic fluctuations and the industrial revolution had a much greater impact on these industries than on grain and drainage mills so only very few are left.

Construction of mills spread to the Cape Colony in the seventeenth century. The early tower mills did not survive the gales of the Cape Peninsula, so in 1717, the Heeren XVII sent carpenters, masons, and materials to construct a durable mill. The mill, completed in 1718, became known as the Oude Molen and was located between Pinelands Station and the Black River. Long since demolished, its name lives on as that of a Technical school in Pinelands. By 1863, Cape Town could boast 11 mills stretching from Paarden Eiland to Mowbray.[26]

Wind turbines

A wind turbine is a windmill-like structure specifically developed to generate electricity. They can be seen as the next step in the development of the windmill. The first wind turbines were built by the end of the nineteenth century by Prof James Blyth in Scotland (1887),[27] Charles F. Brush in Cleveland, Ohio (1887–1888)[28][29] and Poul la Cour in Denmark (1890s). La Cour's mill from 1896 later became the local powerplant of the village Askov. By 1908 there were 72 wind-driven electric generators in Denmark, ranging from 5 to 25 kW. By the 1930s, windmills were widely used to generate electricity on farms in the United States where distribution systems had not yet been installed, built by companies such as Jacobs Wind, Wincharger, Miller Airlite, Universal Aeroelectric, Paris-Dunn, Airline, and Winpower. The Dunlite Corporation produced turbines for similar locations in Australia.

Forerunners of modern horizontal-axis utility-scale wind generators were the WIME-3D in service in Balaklava USSR from 1931 until 1942, a 100-kW generator on a 30-m (100-ft) tower,[30] the Smith-Putnam wind turbine built in 1941 on the mountain known as Grandpa's Knob in Castleton, Vermont, USA of 1.25 MW[31] and the NASA wind turbines developed from 1974 through the mid-1980s. The development of these 13 experimental wind turbines pioneered many of the wind turbine design technologies in use today, including: steel tube towers, variable-speed generators, composite blade materials, and partial-span pitch control, as well as aerodynamic, structural, and acoustic engineering design capabilities. The modern wind power industry began in 1979 with the serial production of wind turbines by Danish manufacturers Kuriant, Vestas, Nordtank, and Bonus. These early turbines were small by today's standards, with capacities of 20–30 kW each. Since then, commercial turbines have increased greatly in size, with the Enercon E-126 capable of delivering up to 7 MW, while wind turbine production has expanded to many countries.

As the 21st century began, rising concerns over energy security, global warming, and eventual fossil fuel depletion led to an expansion of interest in all available forms of renewable energy. Worldwide, many thousands of wind turbines are now operating, with a total nameplate capacity of 194,400 MW.[32] Europe accounted for 48% of the total in 2009.

Windpumps

Windpump (known where they are in use as windmills) are used extensively on farms and ranches in the United States, Canada, Southern Africa, and Australia. These mills feature a large number of blades, so they turn slowly with considerable torque in low winds and are self-regulating in high winds. A tower-top gearbox and crankshaft convert the rotary motion into reciprocating strokes carried downward through a rod to the pump cylinder below. Such mills pumped water and powered feed mills, saw mills, and agricultural machinery. The farm windpump was invented by Daniel Halladay in 1854.[33][34] In early California and some other states, the windmill was part of a self-contained domestic water system including a hand-dug well and a redwood water tower supporting a redwood tank and enclosed by redwood siding (tankhouse). During the late 19th century steel blades and steel towers replaced wooden construction. At their peak in 1930, an estimated 600,000 units were in use.[35] Firms such as U.S. Wind Engine and Pump Company, Challenge Wind Mill and Feed Mill Company, Appleton Manufacturing Company, Star, Eclipse, Fairbanks-Morse, and Aermotor became the main suppliers in North and South America.

In Australia, the Griffiths Brothers at Toowoomba manufactured windmills from 1876, with the trade name Southern Cross Windmills in use from 1903. These became an icon of the Australian rural sector by utilizing the water of the Great Artesian Basin.[36]

See also

References

- ^ "Mill definition". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ "Windmill definition stating that a windmill is a mill or machine operated by the wind". Merriam-webster.com. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ a b Gregory, R. The Industrial Windmill in Britain. Phillimore, 2005

- ^ Dietrich Lohrmann, "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 77, Issue 1 (1995), pp.1-30 (10f.)

- ^ A.G. Drachmann, "Heron's Windmill", Centaurus, 7 (1961), pp. 145-151

- ^ Lucas, Adam (2006). Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology. Brill Publishers. p. 105. ISBN 90-04-14649-0.

- ^ Sathyajith, Mathew (2006). Wind Energy: Fundamentals, Resource Analysis and Economics. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-3-540-30905-5.

- ^ a b Wailes, R. Horizontal Windmills. London, Transactions of the Newcomen Society vol.XL 1967-68 pp125-145

- ^ دانره المعارف بزرگ اسلامی - اصطخري، ابواسحاق[dead link]

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Donald Routledge Hill (1986). Islamic Technology: An illustrated history, p. 54. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42239-6.

- ^ Dietrich Lohrmann, "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 77, Issue 1 (1995), pp. 1–30 (8)

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, May 1991, p. 64–69. (cf. Donald Routledge Hill, Mechanical Engineering)

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 560.

- ^ Hills, R L. Power from Wind: A History of Windmill Technology. Cambridge University Press 1993

- ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (2007), Shadows in the Desert, Osprey Publishing, p. 280, ISBN 1-84603-108-7

- ^ Lynn White Jr. Medieval technology and social change (Oxford, 1962) p. 86 & p. 161–162

- ^ Lucas, Adam (2006), Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology, Brill Publishers, pp. 106–7, ISBN 90-04-14649-0

- ^ Bent Sorensen (November 1995), "History of, and Recent Progress in, Wind-Energy Utilization", Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 20 (1): 387–424, doi:10.1146/annurev.eg.20.110195.002131

- ^ Laurence Turner, Roy Gregory (2009). Windmills of Yorshire. Catrine, East Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 9781840334753.

- ^ Lynn White Jr., Medieval technology and social change (Oxford, 1962) p. 87.

- ^ Martin Watts (2006). Windmills. Osprey Publishing. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7478-0653-0.

- ^ a b c "Wind powered factories: history (and future) of industrial windmills". Low-tech Magazine. 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Wailes, Rex (1954), The English Windmill, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 99–104

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Victorian Farm, Episode 1. Directed and produced by Naomi Benson. BBC Television

- ^ a b Endedijk, L and others. Molens, De Nieuwe Stockhuyzen. Wanders. 2007. ISBN 978-90-400-8785-1

- ^ "Local Windmills". Mostertsmill.co.za. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Shackleton, Jonathan. "World First for Scotland Gives Engineering Student a History Lesson". The Robert Gordon University. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ [Anon, 1890, 'Mr. Brush's Windmill Dynamo', Scientific American, vol 63 no. 25, 20th Dec, p. 54]

- ^ History of Wind Energy in Cutler J. Cleveland,(ed) Encyclopedia of Energy Vol.6, Elsevier, ISBN 978-1-60119-433-6, 2007, pp. 421-422

- ^ Erich Hau, Wind turbines: fundamentals, technologies, application, economics, Birkhäuser, 2006 ISBN 3-540-24240-6, page 32, with a photo

- ^ The Return of Windpower to Grandpa's Knob and Rutland County, Noble Environmental Power, LLC, 12 November 2007. Retrieved from Noblepower.com website 10 January 2010. Comment: this is the real name for the mountain the turbine was built, in case you wondered.

- ^ Global wind energy council

- ^ americanheritage.com

- ^ "fnal.gov". fnal.gov. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Paul Gipe, Wind Energy Comes of Age, John Wiley and Sons, 1995 ISBN 0-471-10924-X, pages 123-127

- ^ Bruce Millet, Triumph of the Griffiths Family (1984) (retrieved 10-12-2013)

Further reading

- Chartrand. French Fortresses in North America 1535–1763: Quebec, Montreal, Louisbourg and New Orleans.

- Drachmann, A.G. (1961) "Heron's Windmill", Centaurus, 7.

- Gregory, Roy and Laurence Turner (2009) Windmills of Yorkshire ISBN 978-1-84033-475-3.

- Hassan, Ahmad Y., Donald Routledge Hill (1986). Islamic Technology: An illustrated history. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42239-6.

- Lohrmann, Dietrich (1995) "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 77, Issue 1

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Shepherd, Dennis G. (1990) Historical Development of the Windmill, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, NASA Contractor Report 4337 DOE/NASA.5266-1, prepared for National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Lewis Research Center & Office of Management, Scientific and Technical Information Division, DOI:10.1115/1.802601.

- Tunis, Edwin (1999), Colonial living, The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-6227-2, pp. 72 and 73.

- Vowles, Hugh Pembroke: "An Enquiry into Origins of the Windmill", Journal of the Newcomen Society, Vol. 11 (1930–31)