IBM: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 218.186.9.2 (talk) to last version by Blondinm |

title |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{copyedit}} |

{{copyedit}} |

||

'''IBM''' |

|||

{{Infobox_Company | |

{{Infobox_Company | |

||

company_name = International Business Machines Corporation | |

company_name = International Business Machines Corporation | |

||

Revision as of 03:25, 6 September 2006

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. |

IBM

| |

| Company type | Public (NYSE: IBM) |

|---|---|

| Industry | Computer hardware Computer software Consulting IT Services |

| Founded | 1888, incorporated 1911 |

| Headquarters | Armonk, New York, USA |

Key people | Samuel J. Palmisano, Chairman & CEO Mark Loughridge SVP & CFO Dan Fortin, President (Canada) Frank Kern, President (Asia Pacific) Nick Donofrio, EVP (Innovation & Technology) Colleen Arnold, President IOT Northeast Europe Dominique Cerutti, President IOT Southwest Europe |

| Products | See complete products listing |

| Revenue | |

(10.5% operating margin[2]) | |

(9.3% profit margin[2]) | |

| Total assets | 123,380,000,000 United States dollar (2018) |

Number of employees | 329,373 (2005)[2] |

| Subsidiaries | ADSTAR Informix Iris Associates Lotus Software Rational Software Sequent Computer Systems Tivoli Systems, Inc. |

| Website | www.ibm.com |

International Business Machines Corporation (IBM, or, colloquially, Big Blue; NYSE: IBM) is a multinational computer technology corporation headquartered in Armonk, New York, USA. The company is one of the few information technology companies with a continuous history dating back to the 19th century; it was founded in 1888 and incorporated (as Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (C-T-R)) on June 15 1911, and listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1916. IBM manufactures and sells computer hardware, software, infrastructure services, hosting services, and consulting services in areas ranging from mainframe computers to nanotechnology.[citation needed] With almost 330,000 employees worldwide and revenues of US$91 billion[1] annually (figures from 2005), IBM is the largest information technology company in the world, and holds more patents than any other technology company.[3]

Since 2001, services and consulting (Global Service) revenues have been larger than those from manufacturing (Hardware).[4] Significantly, IBM has also been steadily increasing its workforce in developing countries (notably, in IBM India) and retrenching in the US and Europe.[5][6][7] Samuel J. Palmisano was elected CEO on January 29 2002 after having led IBM's Global Services, and helping it to become a business with $100 billion in backlog in 2004.[8] Palmisano replaced Louis V. Gerstner, who held the job from 1993 to 2002, taking over from John Akers, who left during a period of financial difficulty for the company.

IBM has engineers and consultants in over 170 countries and IBM Research has eight laboratories, all located in the Northern Hemisphere, with five of those locations outside of the United States.[9] IBM employees have earned five Nobel Prizes, four Turing Awards, five National Medals of Technology, and five National Medals of Science.[10]

As a chip maker IBM is among the Worldwide Top 20 Semiconductor Sales Leaders.

History

1888 – 1924: The founding of IBM

IBM's history dates back decades before the development of electronic computers when it developed punched card data processing equipment. It originated as the Computing Tabulating Recording (CTR) Corporation, which was incorporated on June 15 1911 in Endicott, New York a few miles west of Binghamton.

CTR was formed through a merger of three separate corporations: Tabulating Machine Corporation (founded 1896 in Washington D.C.), the Computing Scale Corporation (founded 1901 in Dayton, Ohio) and the International Time Recording Company (founded 1900 in Endicott, NY). The president of the Tabulating Machine Corporation at that time was Herman Hollerith, who had founded the company. The key person behind the merger was financier Charles Flint, who brought together the founders of the three companies to propose a merger and remained a member of the board of CTR until his retirement in 1930.[11]

Thomas J. Watson Sr., the founder of IBM, became General Manager of CTR in 1914 and President in 1915. In 1917, the CTR entered the Canadian market under the name of International Business Machines Co., Limited and in February 14 1924, CTR changed its name to International Business Machines Corporation.

The companies that merged to form CTR manufactured a wide range of products, including employee time-keeping systems, weighing scales, automatic meat slicers, and most importantly for the development of the computer, punched card equipment. Over time CTR came to focus purely on the punched card business, and ceased its involvement in the other activities.

1930s – 1940s: World War II and Holocaust era

During World War II, IBM manufactured the Browning Automatic Rifle and the M1 Carbine. Allied military forces widely utilized IBM's tabulating equipment for military accounting, logistics, and other War-related purposes. There was extensive use of IBM punch-card machines for calculations made at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project for developing the first atomic bombs; this has been notably discussed by Richard Feynman in his book, Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!. During the War IBM also built the Harvard Mark I for the U.S. Navy, the first large-scale automatic digital computer in the U.S.

In 2001, author Edwin Black published IBM and the Holocaust (ISBN 0-609-80899-0), a book documenting how IBM's New York headquarters and CEO Thomas J. Watson acted through its overseas subsidiaries to provide the Third Reich with punch card machines knowing that the machines could help the Nazis conquer Europe and destroy European Jewry. The book extensively quoted from numerous IBM and governmental memos and letters chronicling how IBM in New York, IBM's Geneva office and Dehomag, its German subsidiary, were intimately involved in supporting Nazi oppression. Black also published IBM's own internal reports admitting that these machines made the Nazis much more efficient in their efforts. The 2003 documentary film The Corporation showed close-ups of several documents including IBM code sheets for concentration camps taken from the files of the National Archives.

Shortly after the war, IBM recovered the profit made from their Hollerith departments in the concentration camps, the printing of millions of punchcards used to keep track of the prisoners, the custom-built punchcard systems, etc.

IBM asserts that, since their German subsidiary came under control by the Nazi authorities, they were not responsible for their role in the holocaust.[12]. As in many cases, when the US entered the war, the Reich left in place the original IBM managers who continued their contacts via Geneva.

1950s: Air Force and airline projects

In the 1950s, IBM became a chief contractor for developing computers for the United States Air Force's automated defense systems. Working on the SAGE anti-aircraft system, IBM gained access to crucial research being done at MIT, working on the first real-time, digital computer (which included many other advancements such as an integrated video display, magnetic core memory, light guns, the first effective algebraic computer language, analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog conversion techniques, digital data transmission over telephone lines, duplexing, multiprocessing, and networks). IBM built fifty-six SAGE computers at the price of US$30 million each, and at the peak of the project devoted more than 7,000 employees (20% of its then workforce) to the project. More valuable to the company in the long run than the profits, however, was the access to cutting-edge research into digital computers being done under military auspices. IBM neglected, however, to gain an even more dominant role in the nascent industry by allowing the RAND Corporation to take over the job of programming the new computers, because, according to one project participant (Robert P. Crago), "we couldn't imagine where we could absorb two thousand programmers at IBM when this job would be over some day, which shows how well we were understanding the future at that time"[13] IBM would use its experience designing massive, integrated real-time networks with SAGE to design its SABRE airline reservation system, which met with much success.

1960s – 1980s: Success

IBM was the largest of the eight major computer companies (with UNIVAC, Burroughs, Scientific Data Systems, Control Data Corporation, General Electric, RCA and Honeywell) through most of the 1960s. People in this business would talk of "IBM and the seven dwarfs", given the much smaller size of the other companies or of their computer divisions (IBM produced approximately 70 % of all computers in 1964).[14]

In 1970, GE sold most of its computer business to Honeywell and in 1971, RCA sold its computing division to Sperry Rand. With only Burroughs, UNIVAC, NCR, Control Data, and Honeywell producing mainframes, people then talked of "IBM and the BUNCH."[14]

Most of those companies are now long gone as IBM competitors, except for Unisys, which is the result of multiple mergers that included UNIVAC and Burroughs. NCR and Honeywell dropped out of the general mainframe and mini sector and concentrated on lucrative niche markets, NCR's being cash registers (hence the name, National Cash Register), and Honeywell becoming the market leader in thermostats. General Electric remains one of the world's largest companies, but no longer operates in the computer market. The IBM computer, the IBM mainframe, that earned it its position in the market at that time is still growing today. It was originally known as the IBM System/360 and, in far more modern 64-bit form, is now known as the IBM System z9.

IBM's success in the mid-1960s led to inquiries as to IBM antitrust violations by the U.S. Department of Justice, which filed a complaint for the case U.S. v. IBM in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, on January 17 1969. The suit alleged that IBM violated the Section 2 of the Sherman Act by monopolizing or attempting to monopolize the general purpose electronic digital computer system market, specifically computers designed primarily for business. Litigation continued until 1983, and had a significant impact on the company's practices. In 1973, IBM was ruled to have created a monopoly via its 1956 patent-sharing agreement with Sperry-Rand in the decision of Honeywell v. Sperry Rand, a decision that invalidated the patent on the ENIAC.

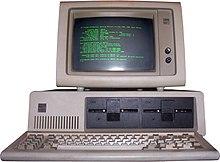

The company hired Don Estridge at the IBM Entry Systems Division in Boca Raton, Florida. With a team known as chess, they built the IBM PC, released on August 11 1981. Although not cheap, at a base price of US$1,565 it was affordable for businesses — and it was business that purchased the PC. However it was not the corporate computer department that was responsible for this, for the PC was not seen as a proper computer. It was generally well-educated middle managers that saw the potential — once the revolutionary VisiCalc spreadsheet, the killer app, had been ported to the PC as the clone, Lotus 1-2-3. Reassured by the IBM name, they began buying the machines on their own budgets to help do the calculations they had learned at business school.

1990s

On October 5, 1992, at the COMDEX computer expo, IBM announced the first Thinkpad laptop computer, the 700c. The computer, which then cost US$ 4350, included a 25 MHz Intel 80486SL processor, a 10.4-inch active matrix display, removable 120 MB hard drive, 4 MB RAM (expandable to 16 MB) and a TrackPoint II pointing device.[15]

On January 19 1993 IBM announced a US$4.97 billion loss for the 1992 financial year, which was at that time the largest single-year corporate loss in U.S. history. Since that loss, IBM has made major changes in its business activities, shifting its focus significantly away from components and hardware and towards software and services.

2000 - 2006

In 2002, IBM strengthened its business advisory capabilities by acquiring the consulting arm of professional services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. The company is increasingly focused on business solution-driven consulting, services and software, with emphasis also on high-value chips and hardware technologies; as of 2005 it employs about 195,000 technical professionals. That total includes about 350 Distinguished Engineers and 60 IBM Fellows, its most-senior engineers.

In 2002, IBM announced the beginning of a US$10 billion program to research and implement the infrastructure technology necessary to be able to provide supercomputer-level resources "on demand" to all businesses as a metered utility.[16] The program has since then been implemented.[17]

IBM has steadily increased its patent portfolio since the early 1990s, which is valuable for cross-licensing with other companies. In every year from 1993 to 2005, IBM has been granted significantly more U.S. patents than any other company. The thirteen-year period has resulted in over 31,000 patents for which IBM is the primary assignee.[3] In 2003, IBM earned 3415 patents, breaking the US record for patents in a single year.[18]

Protection of the company's intellectual property has grown into a business in its own right, generating over $10 billion dollars to the bottom line for the company during this period.[19][20] A 2003 Forbes article quotes Paul Horn, head of IBM Research, saying that IBM has generated $1 billion in profit by licensing intellectual property.[21]

In 2004, IBM announced the proposed sale of its PC business to Chinese computer maker Lenovo Group, which is partially owned by the Chinese government, for US$650 million in cash and US$600 million in Lenovo stock. The deal was approved by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States in March 2005, and completed in May 2005. IBM will have a 19% stake in Lenovo, which will move its headquarters to New York State and appoint an IBM executive as its chief executive officer. The company will retain the right to use certain IBM brand names for an initial period of five years. As a result of the purchase, Lenovo inherited a product line that featured the ThinkPad, a line of laptops that had been one of IBM's most successful products.

Of late, IBM has shifted much of its focus to the provision of business consulting & re-engineering services from its hardware & technology focus. The new IBM has enhanced global delivery capabilities in consulting, software and technology based process services - and this change is reflected in its top-line.[22]

On June 20 2006, IBM and Georgia Institute of Technology jointly announced a new record in silicon-based chip speed at 500GHz. This was done by freezing the chip to -451 °F (Template:FahrenheitToCelsius °C) using liquid helium and is not comparable to CPU speed. The chip operated at about 350GHz at room temperature.[23]

Projects

BlueEyes

BlueEyes[24] is the name of a human recognition venture initiated by IBM to allow people to interact with computers in a more natural manner. The technology aims to enable devices to recognize and use natural input, such as facial expressions. The initial developments of this project include scroll mice and other input devices that sense the user's pulse, monitor his or her facial expressions, and the movement of his or her eyelids.

Eclipse

Eclipse is a platform-independent software framework written in the Java programming language. Eclipse was originally a proprietary product developed by IBM as a successor of its VisualAge family of tools. As of 2006, Eclipse is managed by the non-profit Eclipse Foundation and the source code is released under the free software, open source Eclipse Public License.

alphaWorks

Free software available at alphaWorks, IBM's source for emerging software technology:

- Flexible Internet Evaluation Report Architecture: A highly flexible architecture for the design, display, and reporting of Internet surveys.

- History Flow Visualization Application: A tool for visualizing dynamic, evolving documents and the interactions of multiple collaborating authors.

- IBM Performance Simulator for Linux on POWER: A tool that provides users of Linux on Power a set of performance models for IBM's POWER processors.

- Database File Archive And Restoration Management: An application for archiving and restoring hard disk files whose file references are stored in a database.

- Policy Management for Autonomic Computing: A policy-based autonomic management infrastructure that simplifies the automation of IT and business processes. (This is an ETTK technology.)

- FairUCE: A spam filter that stops spam by verifying sender identity instead of filtering content.

- Unstructured Information Management Architecture (UIMA) SDK: A Java SDK that supports the implementation, composition, and deployment of applications working with unstructured information.

Extreme Blue

Designed as a cross-disciplinary high-profile technology initiative, Extreme Blue is designed to pair up experienced IBM engineers, talented interns, and business managers to develop high-value technology. Great emphasis is placed on emerging business needs and the technologies that can solve them. Sites are operated in San Jose, California, Austin, Texas, and Raleigh, North Carolina, as well as outside the United States.

These projects tend to involve rapid-prototyping of high-profile software or hardware projects and business opportunities. Entry is competitive, both for interns and for IBM employees seeking career growth opportunities with a management focus.

Gaming

IBM develops processing chips for gaming consoles. The Xbox 360 contains IBM's tri-core chipset Xenon. At the request of Microsoft, IBM was able to design the chip and ramp up to production volumes in less than 24 months (with co-production at Chartered Semiconductor Manufacturing in Singapore.)[25] Meanwhile, Sony's PlayStation 3 will feature the Cell, a new chip designed by IBM, Toshiba, and Sony in a joint venture. The Cell is already slated for use in other systems (Toshiba plans to use it on HDTVs), unlike the Xbox 360 chip, whose plans are owned by Microsoft. The Nintendo Wii will, like its predecessor, the GameCube, feature an IBM chip (codenamed Broadway).

In May 2002, IBM and Butterfly.net, Inc. announced the Butterfly Grid, a commercial grid for the online video gaming market.[26] In March 2006, IBM announced separate agreements with Hoplon Infotainment, Online Game Services Incorporated (OGSI) and RenderRocket. The deals included on-demand (for Hoplon Infotainment and RenderRocket) and blade servers (for OGSI).[27]

Big Blue

There are different theories as to where IBM's nickname Big Blue originates from. One theory is that blue comes from the color of the big, room-sized, mainframes that IBM installed in the 1950s and 1960s[28] and that the nickname was coined by business writers.[29] A second theory is the blue comes from the colour of IBM's logo,[30] and a third theory is that it comes from the fact that IBM executives wore blue suits.[28]

Corporate culture

IBM has often been described as having a sales-centric or a sales-oriented business culture. Traditionally, many of its executives and general managers would be chosen from its sales force. In addition, middle and top management would often be enlisted to give direct support to salesmen in the process of making sales to important customers.

For most of the 20th century, a blue suit, white shirt, and a dark tie was the public uniform of IBM employees. But by the 1990s, IBM relaxed these codes; the dress and behavior of its employees does not differ appreciably from that of their counterparts in large technology companies.

In 2003, IBM embarked on an ambitious project to rewrite company values using its Jam technology -- Intranet-based online discussions on key business issues for a limited time, involving more than 50,000 employees over 3 days in this case. Jam technology includes sophisticated text analysis software (eClassifier) to mine online comments for themes, and Jams have now been used six times internally at IBM. As a result of the 2003 Jam, the company values were updated to reflect three modern business, marketplace and employee views: "Dedication to every client's success", "Innovation that matters - for our company and for the world", "Trust and personal responsibility in all relationships."[31]

In 2004, another Jam was conducted in which more than 52,000 employees exchanged best practices for 72 hours. This event was focused on finding actionable ideas to support implementation of the values identified previously. A new post-Jam Ratings event was developed to allow IBMers to select key ideas that support the values. (For further information, see Harvard Business Review, December, 2004, interview with IBM Chairman Sam Palmisano.)

IBM has, since March 1998 when it announced support for Linux, been influenced by the open source movement.[32] The company invests billions of dollars in services and software based on Linux through the IBM Linux Technology Center, which includes over 300 Linux kernel developers.[33] IBM has also released code under different open-source licenses, for example the platform-independent software framework Eclipse (worth circa 40 million US$ at the time of the donation)[34] and the java-based relational database management system (RDBMS) Apache Derby. IBM's open source involvement has not been trouble-free, however; see SCO v. IBM.

Corporate affairs

Diversity and workforce issues

IBM's efforts to promote workforce diversity and equal opportunity date back at least to World War I, when the company hired disabled veterans. IBM was the only technology company ranked in Working Mother magazine's Top 10 for 2004, and one of two technology companies in 2005 (the other company being Hewlett-Packard).[35][36]

The company has traditionally resisted labor union organizing, although unions represent some IBM workers outside the United States. Alliance@IBM, part of the Communications Workers of America, is trying to organize IBM in the U.S. with very little success.

In the 1990s, two major pension program changes, including a conversion to a cash balance plan, resulted in an employee class action lawsuit alleging age discrimination. IBM employees won the lawsuit and arrived at a partial settlement, although appeals are still underway.

Historically IBM has had a good reputation of long-term staff retention with few large scale layoffs. In more recent years there have been a number of broad sweeping cuts to the workforce as IBM attempts to adapt to changing market conditions and a declining profit base. After posting weaker than expected revenues in the first quarter of 2005, IBM eliminated 14,500 positions from its workforce, predominantly in Europe. On June 8 2005, IBM Canada Ltd. eliminated approximately 700 positions. IBM projects these as part of a strategy to 'rebalance' its portfolio of professional skills & businesses. IBM India and other IBM offices in China, the Philippines and Costa Rica have been witnessing a recruitment boom and steady growth in number of employees.

On October 10 2005, IBM became the first major company in the world to formally commit to not using genetic information in its employment decisions. This came just a few months after IBM announced its support of the National Geographic Society's Genographic Project.

Logos

-

The logo that was used from 1924 to 1946. The logo is in a form intended to suggest a globe, girdled by the word "International."

-

The logo that was used from 1947 to 1956. The familiar "globe" was replaced with the simple letters "IBM" in a typeface called "Beton Bold."

-

The logo that was used from 1956 to 1972. The letters "IBM" took on a more solid, grounded and balanced appearance.

-

In 1972, the horizontal stripes now replaced the solid letters to suggest "speed and dynamism."

Corporate governance

Current members of the board of directors of IBM are: Cathleen Black, Ken Chenault, Juergen Dormann, Michael Eskew, Shirley Ann Jackson, Charles F. Knight, Minoru Makihara, Lucio Noto, James W. Owens (effective 1 March 2006), Samuel J. Palmisano, Joan Spero, Sidney Taurel, Charles Vest, and Lorenzo Zambrano.

See also

- IBM PC compatible (or IBM PC clone)

- List of IBM acquisitions and spinoffs

- List of IBM products

- List of commercial failures in computer technology

- SCO v. IBM

References and footnotes

- ^ a b c d "IBM Stock Report". Morningstar, Inc. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ a b c "IBM: Company Overview". Reuters. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ a b "IBM maintains patent lead, moves to increase patent quality". 2006-01-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ 2002 IBM annual report: Financial only (pdf). IBM. p. 64. Retrieved 2006-07-23.

- ^ "Big Blue Shift". 2006-06-05. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM wakes up to India's skills". 2006-06-05. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM cuts 13000 employees, mostly in Europe". 2005-05-05. Retrieved 2006-06-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Personal biography". March 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Worldwide IBM Research Locations". IBM. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

- ^ "Awards & Achievements". IBM. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ "IBM Archives: Charles R. Flint".

- ^ "IBM Statement on Nazi-era Book and Lawsuit". IBM. 2001-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wendover, Robert (2003). High Performance Hiring. Thomson Crisp Learning. p. 179. ISBN 1-56052-666-1.

- ^ a b W. Pugh, Emerson (1995-02-01). Building IBM. pp. 296–297. ISBN 0-262-16147-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ "IBM's ThinkPad turns 10". CNET News.com. 2002-10-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|writer=ignored (help) - ^ Spooner, John G. (2002-10-30). "IBM talks up 'computing on demand'". CNET.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lamonica, Martin (2004-03-02). "IBM fills in on-demand picture". CNET.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM breaks U.S. patent record". IBM. 2004-01-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ John Teresko (2003-03-01). "IBM's Patent/Licensing Connection". IndustryWeek.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Patent Licensing: Another Way to Enhance Return on Investment". Inc. (magazine). 2001-08-09. Archived from the original on 2002-07-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM's Path From Invention To Income". Forbes. 2003-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Can Big Blue Succeed In BPO?". Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. 2004-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Toon, John (2006-06-20). "Georgia Tech/IBM Announce New Chip Speed Record". Georgia Institute of Technology.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM Almaden Research Center".

- ^ "IBM delivers Power-based chip for Microsoft Xbox 360 worldwide launch". IBM. 2005-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Butterfly and IBM introduce first video game industry computing grid". IBM. 2002-05-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM joins forces with game companies around the world to accelerate innovation". IBM. 2006-03-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Logos, Letterheads & Business Cards: Design for Profit. Rotovision. 2004. p. 15. ISBN 2-88046-750-0.

- ^ Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde. State University of New York Press. 2006. p. 228. ISBN 0-7914-6787-2.

- ^ The Essential Guide to Computing: The Story of Information Technology. Publisher: Prentice Hall PTR. p. 55. ISBN 0-13-019469-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Samuel J. Palmisano (2004-04-27). "Speeches". IBM.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "IBM launches biggest Linux lineup ever". IBM. 1999-03-02. Archived from the original on 1999-11-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Farrah Hamid (2006-05-24). "IBM invests in Brazil Linux Tech Center". LWN.net.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Interview: The Eclipse code donation". IBM. 2001-11-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "100 best companies for working mothers 2004". Working Mother Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 2004-10-17.

- ^ "100 best companies 2005". Working Mother Media, Inc. Retrieved 2006-06-26.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- Gerstner, Jr., Louis V. (2002). Who Says Elephants Can't Dance? HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-715448-8.

- Black, Edwin (2001-02-12). IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation. New York: Crown Publishing Group. p. 528. ISBN 0-609-60799-5.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

| Tauqeer Ahmed Khan | 2001 | IBM vs. Pakistan: The Struggle for the Future | ISBN n/a |

| Robert Sobel | 1981 | IBM: Colossus in Transition | ISBN 0-8129-1000-1 |

| Robert Sobel | 1981 | Thomas Watson, Sr.: IBM and the Computer Revolution (biography of Thomas J. Watson) | ISBN 1-893122-82-4 |

External links

- Official website, including links for News, Press Room, Syndicated Information, On Demand Business, eServers, Grid computing, alphaWorks, and History

- The IBM Songbook; Ever Onward (needs Flash)

- IBM Research, with links to Cambridge, Massachusetts and Zurich facilities, among others

- IBM Antitrust Suit Records 1950-1982

- IBM Jargon Dictionary

- IBM Compatibles

- developerWorks - IBM's resource for software developers, including blogs

- power.org

- IBM Executive Compensation

- IBMeye fan blog

- History of IBM Watson Research Laboratory at Columbia University

- Mainframe blog

- parody video: IBM Mainframe meets "The Office"