Bridgeport, Connecticut, Centennial half dollar: Difference between revisions

Not a valid speedy reason |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:disgust}} |

|||

<div style="display:none"> |

|||

{{Infobox coin |

{{Infobox coin |

||

| Country = United States |

| Country = United States |

||

Revision as of 05:15, 16 March 2020

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

Disgust (Middle French: desgouster, from Latin gustus, 'taste') is an emotional response of rejection or revulsion to something potentially contagious[1] or something considered offensive, distasteful or unpleasant. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin wrote that disgust is a sensation that refers to something revolting. Disgust is experienced primarily in relation to the sense of taste (either perceived or imagined), and secondarily to anything which causes a similar feeling by sense of smell, touch, or vision. Musically sensitive people may even be disgusted by the cacophony of inharmonious sounds. Research has continually proven a relationship between disgust and anxiety disorders such as arachnophobia, blood-injection-injury type phobias, and contamination fear related obsessive–compulsive disorder (also known as OCD).[2][3]

Disgust is one of the basic emotions of Robert Plutchik's theory of emotions, and has been studied extensively by Paul Rozin.[4] It invokes a characteristic facial expression, one of Paul Ekman's six universal facial expressions of emotion. Unlike the emotions of fear, anger, and sadness, disgust is associated with a decrease in heart rate.[5]

Evolutionary significance

It is believed that the emotion of disgust has evolved as a response to offensive foods that may cause harm to the organism.[6] A common example of this is found in human beings who show disgust reactions to mouldy milk or contaminated meat. Disgust appears to be triggered by objects or people who possess attributes that signify disease.[7]

Self-report and behavioural studies found that disgust elicitors include:

- body products (feces, urine, vomit, sexual fluids, saliva, and mucus);

- foods (spoiled foods);

- animals (rats, fleas, ticks, lice, snakes, cockroaches, worms, flies, spiders, pigeons and frogs);

- hygiene (visible dirt and "inappropriate" acts [e.g., using an unsterilized surgical instrument]);

- body envelope violations (blood, gore, and mutilation);

- death (dead bodies and organic decay), hard diseases and disasters;

- visible signs of infection[8]

The above-mentioned main disgust stimuli are similar to one another in the sense that they can all potentially transmit infections, and are the most common referenced elicitors of disgust cross-culturally.[10] Because of this, disgust is believed to have evolved as a component of a behavioral immune system in which the body attempts to avoid disease-carrying pathogens in preference to fighting them after they have entered the body. This behavioral immune system has been found to make sweeping generalizations because "it is more costly to perceive a sick person as healthy than to perceive a healthy person as sickly".[11] Researchers have found that sensitivity to disgust is negatively correlated to aggression because feelings of disgust typically bring about a need to withdraw[clarification needed] while aggression results in a need to approach.[12] This can be explained in terms of each of the types of disgust. For those especially sensitive to moral disgust, they would want to be less aggressive because they want to avoid hurting others. Those especially sensitive to pathogen disgust might be motivated by a desire to avoid the possibility of an open wound on the victim of the aggression. Those sensitive to sexual disgust must have some sexual object present to be especially avoidant of aggression.[12] Based on these findings, disgust may be used as an emotional tool to decrease aggression in individuals. Disgust may produce specific autonomic responses, such as reduced blood pressure, lowered heart-rate and decreased skin conductance along with changes in respiratory behaviour.[13]

Research has also found that people who are more sensitive to disgust tend to find their own in-group more attractive and tend to have more negative attitudes toward other groups.[14] This may be explained by assuming that people begin to associate outsiders and foreigners with disease and danger while simultaneously associating health, freedom from disease, and safety with people similar to themselves.

Taking a further look into hygiene, disgust was the strongest predictor of negative attitudes toward obese individuals. A disgust reaction to obese individuals was also connected with views of moral values.[15]

Domains of disgust

Tybur, et al., outlines three domains of disgust: pathogen disgust, which "motivates the avoidance of infectious microorganisms"; sexual disgust, "which motivates the avoidance of [dangerous] sexual partners and behaviors"; and moral disgust, which motivates people to avoid breaking social norms. Disgust may have an important role in certain forms of morality.[16]

Pathogen disgust arises from a desire to survive and, ultimately, a fear of death. He compares it to a "behavioral immune system" that is the 'first line of defense' against potentially deadly agents such as dead bodies, rotting food, and vomit.[16]

Sexual disgust arises from a desire to avoid "biologically costly mates" and a consideration of the consequences of certain reproductive choices. The two primary considerations are intrinsic quality (e.g., body symmetry, facial attractiveness, etc.) and genetic compatibility (e.g., avoidance of inbreeding such as the incest taboo).[16]

Moral disgust "pertains to social transgressions" and may include behaviors such as lying, theft, murder, and rape. Unlike the other two domains, moral disgust "motivates avoidance of social relationships with norm-violating individuals" because those relationships threaten group cohesion.[16]

Gender differences

Women generally report greater disgust than men, especially regarding sexual disgust or general repulsiveness which have been argued to be consistent with women being more selective regarding sex for evolutionary reasons.[17]

Sensitivity to disgust rises during pregnancy, along with levels of the hormone progesterone.[18] Scientists have conjectured that pregnancy requires the mother to "dial down" her immune system so that the developing embryo won't be attacked. To protect the mother, this lowered immune system is then compensated by a heightened sense of disgust.[19]

Because disgust is an emotion with physical responses to undesirable or dirty situations, studies have proven there are cardiovascular and respiratory changes while experiencing the emotion of disgust.[20]

As mentioned earlier, women experience disgust more prominently than men. This is reflected in a study about dental phobia. A dental phobia comes from experiencing disgust when thinking about the dentist and all that entails. 4.6 percent of women compared to 2.7 percent of men find the dentist disgusting.[21]

Non-verbal communication

In a series of significant studies by Paul Ekman in the 1970s, it was discovered that facial expressions of emotion are not culturally determined, but universal across human cultures and thus likely to be biological in origin.[22] The facial expression of disgust was found to be one of these facial expressions. This characteristic facial expression includes slightly narrowed brows, waving the hand back and forth although different elicitors may produce different forms of this expression.[23] It was found that the facial expression of disgust is readily recognizable across cultures.[24] This facial expression is also produced in blind individuals and is correctly interpreted by deaf individuals.[7] This evidence indicates an innate biological basis for the expression and recognition of disgust. The recognition of disgust is also important among species as it has been found that when an individual sees a conspecific looking disgusted after tasting a particular food, he or she automatically infers that the food is bad and should not be eaten.[6] This evidence suggests that disgust is experienced and recognized almost universally and strongly implicates its evolutionary significance.

Facial feedback has also been implicated in the expression of disgust. That is, the making of the facial expression of disgust leads to an increased feeling of disgust. This can occur if the person just wrinkles one's nose without awareness that they are making a disgust expression.[25]

The mirror-neuron matching system found in monkeys and humans is a proposed explanation for such recognition, and shows that our internal representation of actions is triggered during the observation of another's actions.[26] It has been demonstrated that a similar mechanism may apply to emotions. Seeing someone else's facial emotional expressions triggers the neural activity that would relate to our own experience of the same emotion.[27] This points to the universality, as well as survival value of the emotion of disgust.

Children's reactions to a face showing disgust

At a very young age, children are able to identify different, basic facial emotions. If a parent makes a negative face and a positive emotional face toward two different toys, a child as young as five months would avoid the toy associated with a negative face. Young children tend to associate a face showing disgust with anger instead of being able to identify the difference. Adults can make the distinction. The age of understanding seems to be around ten years old.[28]

Cultural differences

Because disgust is partially a result of social conditioning, there are differences among different cultures in the objects of disgust. For example, Americans "are more likely to link feelings of disgust to actions that limit a person's rights or degrade a person's dignity" while Japanese people "are more likely to link feelings of disgust to actions that frustrate their integration into the social world."[29] Furthermore, practices viewed as acceptable in some cultures may be viewed as disgusting in other cultures. In English the concept disgust can apply to both physical and abstract things, but in Hindi and Malayalam languages, the concept does not apply to both.[30]

Disgust is one of the basic emotions recognizable across multiple cultures and is a response to something revolting typically involving taste or sight. Though different cultures find different things disgusting, the reaction to the grotesque things remains the same throughout each culture; people and their emotional reactions in the realm of disgust remain the same.[31]

Neural basis

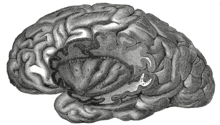

The scientific attempts to map specific emotions onto underlying neural substrates dates back to the first half of the 20th century. Functional MRI experiments have revealed that the anterior insula in the brain is particularly active when experiencing disgust, when being exposed to offensive tastes, and when viewing facial expressions of disgust.[32] The research has supported that there are independent neural systems in the brain, each handling a specific basic emotion.[6] Specifically, f-MRI studies have provided evidence for the activation of the insula in disgust recognition, as well as visceral changes in disgust reactions such as the feeling of nausea.[6] The importance of disgust recognition and the visceral reaction of "feeling disgusted" is evident when considering the survival of organisms, and the evolutionary benefit of avoiding contamination.[6]

Insula

The insula (or insular cortex), is the main neural structure involved in the emotion of disgust.[6][27][33] The insula has been shown by several studies to be the main neural correlate of the feeling of disgust both in humans and in macaque monkeys. The insula is activated by unpleasant tastes, smells, and the visual recognition of disgust in conspecific organisms.[6]

The anterior insula is an olfactory and gustatory center that controls visceral sensations and the related autonomic responses.[6] It also receives visual information from the anterior portion of the ventral superior temporal cortex, where cells have been found to respond to the sight of faces.[34]

The posterior insula is characterized by connections with auditory, somatosensory, and premotor areas, and is not related to the olfactory or gustatory modalities.[6]

The fact that the insula is necessary for our ability to feel and recognize the emotion of disgust is further supported by neuropsychological studies. Both Calder (2000) and Adolphs (2003) showed that lesions on the anterior insula lead to deficits in the experience of disgust and recognizing facial expressions of disgust in others.[33][35] The patients also reported having reduced sensations of disgust themselves. Furthermore, electrical stimulation of the anterior insula conducted during neurosurgery triggered nausea, the feeling of wanting to throw up and uneasiness in the stomach. Finally, electrically stimulating the anterior insula through implanted electrodes produced sensations in the throat and mouth that were "difficult to stand".[6] These findings demonstrate the role of the insula in transforming unpleasant sensory input into physiological reactions, and the associated feeling of disgust.[6]

Studies have demonstrated that the insula is activated by disgusting stimuli, and that observing someone else's facial expression of disgust seems to automatically retrieve a neural representation of disgust.[6][36] Furthermore, these findings emphasize the role of the insula in feelings of disgust.

One particular neuropsychological study focused on patient NK who was diagnosed with a left hemisphere infarction involving the insula, internal capsule, putamen and globus pallidus. NK's neural damage included the insula and putamen and it was found that NK's overall response to disgust-inducing stimuli was significantly lower than that of controls.[33] The patient showed a reduction in disgust-response on eight categories including food, animals, body products, envelope violation and death.[33] Moreover, NK incorrectly categorized disgust facial expressions as anger. The results of this study support the idea that NK had damage to a system involved in recognizing social signals of disgust, due to a damaged insula caused by neurodegeneration.[33]

Disorders

Huntington's disease

Many patients with Huntington's disease, a genetically transmitted progressive neurodegenerative disease, are unable to recognize expressions of disgust in others and also don't show reactions of disgust to foul odors or tastes.[37] The inability to recognize expressions of disgust appears in carriers of the Huntington gene before other symptoms appear.[38] People with Huntington's disease are impaired at recognition of anger and fear, and experience a notably severe problem with disgust recognition.[39]

Major depressive disorder

Patients with major depression have been found to display greater brain activation to facial expressions of disgust.[40] Self-disgust, which is disgust directed towards one's own actions, may also contribute to the relationship between dysfunctional thoughts and depression.[41]

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

The emotion of disgust may have an important role in understanding the neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), particularly in those with contamination preoccupations.[42] In a study by Shapira & colleagues (2003), eight OCD subjects with contamination preoccupations and eight healthy volunteers viewed pictures from the International Affective Picture System during f-MRI scans. OCD subjects showed significantly greater neural responses to disgust-invoking images, specifically in the right insula.[43] Furthermore, Sprengelmeyer (1997) found that the brain activation associated with disgust included the insula and part of the gustatory cortex that processes unpleasant tastes and smells. OCD subjects and healthy volunteers showed activation patterns in response to disgust pictures that differed significantly at the right insula. In contrast, the two groups were similar in their response to threat-inducing pictures, with no significant group differences at any site.[44]

Animal research

With respect to studies using rats, prior research of signs of a conditioned disgust response have been experimentally verified by Grill and Norgren (1978) who developed a systematic test to assess palatability. The Taste Reactivity (TR) test has thus become a standard tool in measuring disgust response.[45] When given a stimulus intraorally which had been previously paired with a nausea-inducing substance, rats will show conditioned disgust reactions. "Gaping" in rats is the most dominant conditioned disgust reaction and the muscles used in this response mimic those used in species capable of vomiting.[46] Studies have shown that treatments that reduced serotonin availability or that activate the endocannabinoid system can interfere with the expression of a conditioned disgust reaction in rats. These researchers showed that as nausea produced conditioned disgust reactions, by administering the rats with an antinausea treatment they could prevent toxin-induced conditioned disgust reactions. Furthermore, in looking at the different disgust and vomiting reactions between rats and shrews the authors showed that these reactions (particularly vomiting) play a crucial role in the associative processes that govern food selection across species.[47]

In discussing specific neural locations of disgust, research has shown that forebrain mechanisms are necessary for rats to acquire conditioned disgust for a specific emetic (vomit-inducing) substance (such as lithium chloride).[48] Other studies have shown that lesions to the area postrema[49] and the parabrachial nucleus of the pons[50] but not the nucleus of the solitary tract[50] prevented conditioned disgust. Moreover, lesions of the dorsal and medial raphe nuclei (depleting forebrain serotonin) prevented the establishment of lithium chloride-induced conditioned disgust.[47]

Non-human primates

Non-human primates display signs of disgust and aversion to biological contaminants. Exposure to bodily excrements that usually elicit disgust reactions in humans, such as feces, semen, or blood, have an impact on primates' feeding preferences.[51] Chimpanzees generally avoid the smells of biological contaminants, but only show a weak tendency to move away from these odors, possibly because olfactory stimuli are not enough to give chimps a high enough threat level to move away.[52] Chimpanzees physically recoil when presented with food items on soft, moist substrates, possibly because in nature, moisture, softness, and warmth are characteristics needed to grow pathogens.[52] These responses are functionally similar to what humans' responses would be to the same kinds of stimuli, indicating that the underlying mechanism for this behavior is similar to ours.[53]

Chimpanzees generally avoid food contaminated with dirt or feces, but most individuals still consume these kinds of contaminated foods.[51] While chimps do show a preference for food items with lower contamination risk, they do not avoid risk altogether, as most humans would. This may be due to a trade-off between the nutritional value of the food items and the risk of infection from the biological contaminants, with the chimps weighing the benefit of the food more heavily than the risk of contamination.[54] In contrast to chimpanzees, Japanese macaques are more sensitive to visual cues of contaminants when there is no accompanying odor.[53] Bonobos are most sensitive to fecal odors and rotten food odors.[55] Overall, primates incorporate various senses in their feeding decisions, with disgust being an adaptive trait that helps them avoid potential parasites and other threats from contaminants.

The most frequently reported disgust-like behavior in non-human primates is expelling bad-tasting food items, but even this behavior is not very common. This might be because primates effectively avoid potentially bad-tasting food items, and food that is avoided cannot be expelled, hence the low observation rate of this behavior.[51] Primates, notably gorillas and chimpanzees, occasionally make facial expressions such as grimacing and tongue protrusions after having bad-tasting food.[56] Individual primate preferences vary widely, some tolerating extremely bitter food, while others are more particular.[53] Taste preferences are more often noticed in high ranking individuals, likely because lower ranked individuals may have to tolerate less-desired foods.[51]

While in humans there is a strong difference in disgust reactions between the two sexes, this difference has not been documented in non-human primates. In humans, women generally report greater disgust than men.[57] In bonobos and chimps, females are not any more avoidant than males of contamination risk.[55] There is some evidence suggesting that juveniles are less contamination-risk avoidant than adults, which is in line with research on the development of the disgust response in humans.[51]

Coprophagy is commonly observed in chimpanzees, possibly suggesting that chimps do not really have a disgust mechanism the way humans do.[58] Coprophagy is usually only done to re-ingest seeds from one's own feces, which is less risky than ingesting others' feces in terms of exposure to new parasites.[59] Additionally, chimps often use leaves and twigs to wipe themselves when they stepped in others' feces instead of removing it with their bare hands.[51] Great apes almost always remove feces from their bodies after accidentally stepping in it, even in instances where it would be beneficial to wait. For example, when grapes are being passed out to chimps and they accidentally step in feces, they almost always take the time to stop and wipe it off even if it means missing out on food.[53]

Unlike in humans, the avoidance of social contamination (ex: staying away from sick conspecifics) is rare in great apes.[60] Instead, great apes often groom sick conspecifics or just treat them with indifference.[51] Additionally, great apes treat products of a sick conspecific such as mucus or blood with interest or indifference.[53] This is in contrast with human disease avoidance, where avoiding those who appear sick is a key feature.

Taken together, studies on the disgust reaction in primates show that disgust is adaptive in primates and that the avoidance of potential sources of pathogens is triggered by the same contaminants as for humans.[61] The adaptive problems that primates faced did not align to the degree that they did for early humans, which is why disgust manifests differently in humans and non-human primates.[62] Differences in disgust responses between humans and non-human primates likely reflects their unique ecological standpoints. Rather than disgust being a unique human emotion, disgust is a continuation of the parasite and infection avoidance behavior found in all animals.[51] One theory explaining the difference is that since primates are largely foragers and never shifted to the hunter-scavenger lifestyle with a diet high in meat, they were never exposed to the new wave of pathogens that humans were exposed to, as well as the selection pressures that would come with this diet. Therefore, the disgust mechanisms in primates remained muted, only strong enough to address the distinct problems primates faced in their evolutionary history.[62] Additionally, disgust-like behavior in great apes should be lower than in humans because they live in less hygienic conditions. Humans' clean habits over generations has reduced how frequently we are exposed to disgust elicitors and has likely expanded the stimuli that would elicit disgust reactions in us. Great apes on the other hand are constantly exposed to disgust elicitors, leading to habituation and a muted form of disgust compared to modern humans.[53]

Morality

Although disgust was first thought to be a motivation for humans to only physical contaminants, it has since been applied to moral and social moral contaminants as well. The similarities between these types of disgust can especially be seen in the way people react to the contaminants. For example, if someone stumbles upon a pool of vomit, they will do whatever possible to place as much distance between themselves and the vomit as possible, which can include pinching the nose, closing the eyes, or running away. Likewise, when a group experiences someone who cheats, rapes, or murders another member of the group, its reaction is to shun or expel that person from the group.[63]

Arguably, there is a completely different construct of the emotion of disgust from the core disgust that can be seen in Ekman's basic emotions. Socio-moral disgust occurs when social or moral boundaries appear to be violated, the socio-moral aspect centers on human violations of the autonomy and dignity of others (e.g., racism, hypocrisy, disloyalty).[64] Socio-moral disgust is different from core disgust. In the 2006 study done by Simpson and colleagues, there was a divergence found in disgust responses between the core elicitors of disgust and the socio-moral elicitors of disgust, suggesting that the makeup of core and socio-moral disgust may be different emotional constructs.[64]

Studies have found that disgust has been known to predict prejudice and discrimination.[65][66] Through passive viewing tasks and functional magnetic resonance researchers were able to provide direct evidence that the insula is largely involved in racially biased perception of facial disgust through two distinct neural pathways: amygdala and insula, both areas of the brain that deal with emotion processing.[64] It was found that racial prejudice elicited disgusted facial expressions. Disgust can also predict prejudice and discrimination towards individuals with obesity.[66] Vertanian, Trewartha and Vanman (2016) showed participants photos of obese targets and non-obese targets performing everyday activities. They found that, compared to non-obese people, obese targets elicited more disgust, more negative attitudes and stereotypes, and a greater desire for a social distance from participants.

Jones & Fitness (2008)[63] coined the term "moral hypervigilance" to describe the phenomenon that individuals who are prone to physical disgust are also prone to moral disgust. The link between physical disgust and moral disgust can be seen in the United States where criminals are often referred to as "slime" or "scum" and criminal activity as "stinking" or being "fishy". Furthermore, people often try to block out the stimuli of morally repulsive images in much the same way that they would block out the stimuli of a physically repulsive image. When people see an image of abuse, rape, or murder, they often avert their gazes to inhibit the incoming visual stimuli from the photograph just like they would if they saw a decomposing body.[citation needed]

Moral judgments can be traditionally defined or thought of as directed by standards such as impartiality and respect towards others for their well-being. From more recent theoretical and empirical information, it can be suggested that morality may be guided by basic affective processes. Jonathan Haidt proposed that one's instant judgments about morality are experienced as a "flash of intuition" and that these affective perceptions operate rapidly, associatively, and outside of consciousness.[67] From this, moral intuitions are believed to be stimulated prior to conscious moral cognitions which correlates with having a greater influence on moral judgments.[67]

Research suggests that the experience of disgust can alter moral judgments. Many studies have focused on the average change in behavior across participants, with some studies indicating disgust stimuli intensifies the severity of moral judgments.[68] Later studies found the reverse effect,[69] and some studies have suggested that the average effect of disgust on moral judgments is small or absent.[70][71][72] Potentially reconciling these effects, one study indicated that the direction and size of the effect of disgust stimuli on moral judgment depends upon an individual's sensitivity to disgust.[73] One effort to reconcile the inconsistent findings suggests that studying the effects of induced disgust on moral judgments alone is insufficient. Instead, the magnitude of experienced disgust appears to be a critical factor. Research by Białek et al. [74] found that self-reported levels of disgust were more predictive of changes in moral judgments than the mere presence of disgust elicitors. This approach may provide a more nuanced understanding of how disgust influences moral decision-making.

The effect also seems to be limited to a certain aspect of morality. Horberg et al. found that disgust plays a role in the development and intensification of moral judgments of purity in particular.[75] In other words, the feeling of disgust is often associated with a feeling that some image of what is pure has been violated. For example, a vegetarian might feel disgust after seeing another person eating meat because he/she has a view of vegetarianism as the pure state-of-being. When this state-of-being is violated, the vegetarian feels disgust. Furthermore, disgust appears to be uniquely associated with purity judgments, not with what is just/unjust or what is harmful/caregiving, while other emotions such as fear, anger, and sadness are "unrelated to moral judgments of purity".[75]

Some other research suggests that an individual's level of disgust sensitivity is due to their particular experience of disgust.[67] One's disgust sensitivity can be either high or low. The higher one's disgust sensitivity is, the greater the tendency to make stricter moral judgments.[67] Disgust sensitivity can also relate to various aspects of moral values, which can have a negative or positive impact. For example, Disgust sensitivity is associated with moral hypervigilance, which means people who have higher disgust sensitivity are more likely to think that other people who are suspects of a crime are more guilty. They also associate them as being morally evil and criminal, thus endorsing them to harsher punishment in the setting of a court.[citation needed]

Disgust is also theorized as an evaluative emotion that can control moral behavior.[67] When one experiences disgust, this emotion might signal that certain behaviors, objects, or people are to be avoided in order to preserve their purity. Research has established that when the idea or concept of cleanliness is made salient then people make less severe moral judgments of others.[67] From this particular finding, it can be suggested that this reduces the experience of disgust and the ensuing threat of psychological impurity diminishes the apparent severity of moral transgressions.[76]

Political orientation

In one study, people of differing political persuasions were shown disgusting images in a brain scanner. In conservatives, the basal ganglia and amygdala and several other regions showed increased activity, while in liberals other regions of the brain increased in activity. Both groups reported similar conscious reactions to the images. The difference in activity patterns was large: the reaction to a single image could predict a person's political leanings with 95% accuracy.[77][78] Later, however, such results have been proven to be mixed, with failed replications and questions about what is actually being measured also raising questions about the generalizability of the findings.[79]

Self-disgust

Although limited research has been done on self-disgust, one study found that self-disgust and severity of moral judgments were negatively correlated.[80] This is in contrast to findings related to disgust, which typically results in harsher judgments of transgressions. This implies that disgust directed towards the self functions very differently from disgust directed towards other people or objects.[80] Self-disgust "may reflect a pervasive condition of self-loathing that makes it difficult to assign deserving punishment to others".[80] In other words, those who feel self-disgust cannot easily condemn others to punishment because they feel that they may also be deserving of punishment. The concept of self-disgust has been implicated in several mental health conditions, including depression,[81] obsessive-compulsive disorder[82] and eating disorders.[83]

Functions

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (February 2018) |

The emotion of disgust can be described to serve as an effective mechanism following occurrences of negative social value, provoking repulsion, and desire for social distance.[84] The origin of disgust can be defined by motivating the avoidance of offensive things, and in the context of a social environment, it can become an instrument of social avoidance.[84] An example of disgust in action can be found from the Bible in the book of Leviticus (See especially Leviticus chapter 11). Leviticus includes direct commandments from God to avoid disgust causing individuals, which included people who were sexually immoral and those who had leprosy.[84] Disgust is known to promote the avoidance of pathogens and disease.[85]

As an effective instrument for reducing motivations for social interaction, disgust can be anticipated to interfere with dehumanization or the maltreatment of persons as less than human.[84] Research was performed which conducted several functional magnetic resonance images (fMRI) in which participants viewed images of individuals from stigmatized groups that were associated with disgust, which were drug addicts and homeless people.[84] What the study found was that people were not inclined in making inferences about the mental conditions of these particular disgust inducing groups.[84] Therefore, examining images of homeless people and drug addicts caused disgust in the response of the people who participated with this study.[84] This study coincides with disgust following the law of contagion, which explains that contact with disgusting material renders one disgusting.[84] Disgust can be applied towards people and can function as maltreatment towards another human being. Disgust can exclude people from being a part of a clique by leading to the view that they are merely less than human. An example of this is if groups were to avoid people from outside of their own particular group. Some researchers have distinguished between two different forms of dehumanization. The first form is the denial of uniquely human traits, examples include: products of culture and modification.[84] The second form is the denial of human nature, examples include: emotionality and personality.[84]

Failure to attribute distinctively human traits to a group leads to animalistic dehumanization, which defines the object group or individual as savage, crude, and similar to animals.[84] These forms of dehumanization have clear connections to disgust.[84] Researchers have proposed that many disgust elicitors are disgusting because they are reminders that humans are not diverse from other creatures.[84] With the aid of disgust, animalistic dehumanization directly reduces one's moral concerns towards excluding members from the outer group.[84] Disgust can be a cause and consequence of dehumanization.[84] Animalistic dehumanization may generate feelings of disgust and revulsion.[84] Feelings of disgust, through rousing social distance, may lead to dehumanization. Therefore, a person or group that is generally connected with disgusting effects and seen as physically unclean may induce moral avoidance.[84] Being deemed disgusting produces a variety of cognitive effects that result in exclusion from the perceived inner group.[84]

Political and legal aspects of disgust

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

The emotion disgust has been noted to feature strongly in the public sphere in relation to issues and debates, among other things, regarding anatomy, sex and bioethics. There is a range of views by different commentators on the role, purpose and effects of disgust on public discourse.

Leon Kass, a bioethicist, has advocated that "in crucial cases...repugnance is the emotional expression of deep wisdom, beyond reason's power fully to articulate it." in relation to bio-ethical issues (See: Wisdom of repugnance).

Martha Nussbaum, a jurist and ethicist, explicitly rejects disgust as an appropriate guide for legislating, arguing the "politics of disgust" is an unreliable emotional reaction with no inherent wisdom. Furthermore, she argues this "politics of disgust" has in the past and present had the effects of supporting bigotry in the forms of sexism, racism and antisemitism and links the emotion of disgust to support for laws against Miscegenation and the oppressive caste system in India. In place of this "politics of disgust", Nussbaum argues for the Harm principle from John Stuart Mill as the proper basis for legislating. Nussbaum argues the harm principle supports the legal ideas of consent, the Age of majority and privacy and protects citizens. She contrasts this with the "politics of disgust" which she argues denies citizens humanity and equality before the law on no rational grounds and cause palpable social harm. (See Martha Nussbaum, From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law). Nussbaum published Hiding From Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law in 2004; the book examines the relationship of disgust and shame to a society's laws. Nussbaum identifies disgust as a marker that bigoted, and often merely majoritarian, discourse employs to "place", by diminishment and denigration, a despised minority. Removing "disgust" from public discourse constitutes an important step in achieving humane and tolerant democracies.

Leigh Turner (2004) has argued that "reactions of disgust are often built upon prejudices that should be challenged and rebutted." On the other hand, writers, such as Kass, find wisdom in adhering to one's initial feelings of disgust. A number of writers[who?] on the theory of disgust find it to be the proto-legal foundation of human law.

Disgust has also figured prominently in the work of several other philosophers. Nietzsche became disgusted with the music and orientation of Richard Wagner, as well as other aspects of 19th century culture and morality. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote widely about experiences involving various negative emotions related to disgust.[86]

The Hydra's Tale: Imagining Disgust

According to the book The Hydra's Tale: Imagining Disgust by Robert Rawdon Wilson,[87] disgust may be further subdivided into physical disgust, associated with physical or metaphorical uncleanliness, and moral disgust, a similar feeling related to courses of action. For example; "I am disgusted by the hurtful things that you are saying." Moral disgust should be understood as culturally determined; physical disgust as more universally grounded. The book also discusses moral disgust as an aspect of the representation of disgust. Wilson does this in two ways. First, he discusses representations of disgust in literature, film and fine art. Since there are characteristic facial expressions (the clenched nostrils, the pursed lips)—as Charles Darwin, Paul Ekman, and others have shown—they may be represented with more or less skill in any set of circumstances imaginable. There may even be "disgust worlds" in which disgust motifs so dominate that it may seem that entire represented world is, in itself, disgusting. Second, since people know what disgust is as a primary, or visceral, emotion (with characteristic gestures and expressions), they may imitate it. Thus, Wilson argues that, for example, contempt is acted out on the basis of the visceral emotion, disgust, but is not identical with disgust. It is a "compound affect" that entails intellectual preparation, or formatting, and theatrical techniques. Wilson argues that there are many such "intellectual" compound affects—such as nostalgia and outrage—but that disgust is a fundamental and unmistakable example. Moral disgust, then, is different from visceral disgust; it is more conscious and more layered in performance.

Wilson links shame and guilt to disgust (now transformed, wholly or partially, into self-disgust) primarily as a consequence rooted in self-consciousness. Referring to a passage in Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook, Wilson writes that "the dance between disgust and shame takes place. A slow choreography unfolds before the mind's-eye."[88]

Wilson examines the claims of several jurists and legal scholars—such as William Ian Miller—that disgust must underlie positive law. "In the absence of disgust", he observes, stating their claim, ". . . there would be either total barbarism or a society ruled solely by force, violence and terror." The moral-legal argument, he remarks, "leaves much out of account."[89] His own argument turns largely upon the human capacity to learn how to control, even to suppress, strong and problematic affects and, over time, for entire populations to abandon specific disgust responses.

Plutchik's Wheel of Emotions

Disgust is the opposite of trust on the emotion wheel.[93] A mild form of disgust is boredom, while a more intense version is loathing.[94]

See also

- Affective neuroscience

- Amygdala

- Aversion therapy

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Contempt

- Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells

- Fear

- Foodborne illness

- Menippean satire

- Nausea

- Papez circuit

- Phobia

- Social neuroscience

- Taboo

- Vomiting

References

- ^ Badour, Christal L.; Feldner, Matthew T. (July 2018). "The Role of Disgust in Posttraumatic Stress". Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. 9 (3): pr.032813. doi:10.5127/pr.032813.

- ^ Husted, D.S.; Shapira, N.A.; Goodman, W.K. (2006). "The neurocircuitry of obsessive–compulsive disorder and disgust". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 30 (3): 389–399. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.11.024. PMID 16443315. S2CID 20685000.

- ^ Cisler, Josh M.; Olatunji, Bunmi O.; Lohr, Jeffrey M.; Williams, Nathan L. (June 2009). "Attentional bias differences between fear and disgust: Implications for the role of disgust in disgust-related anxiety disorders". Cognition & Emotion. 23 (4): 675–687. doi:10.1080/02699930802051599. PMC 2892866. PMID 20589224.

- ^ Young, Molly (27 December 2021). "How Disgust Explains Everything". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021.

- ^ Rozin, Paul; Haidt, Jonathan; McCauley, Clark (2018). "Disgust". In Barrett, Lisa Feldman; Lewis, Michael; Haviland-Jones, Jeannette M. (eds.). Handbook of Emotions. Guilford Publications. pp. 815–834. ISBN 978-1-4625-3636-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wicker, Bruno; Keysers, Christian; Plailly, Jane; Royet, Jean-Pierre; Gallese, Vittorio; Rizzolatti, Giacomo (October 2003). "Both of Us Disgusted in My Insula". Neuron. 40 (3): 655–664. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00679-2. PMID 14642287.

- ^ a b Oaten, M.; Stevenson, R. J.; Case, T. I. (2009). "Disgust as a Disease-Avoidance Mechanism". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (2): 303–321. doi:10.1037/a0014823. PMID 19254082.

- ^ Curtis, Valerie; Biran, Adam (December 2001). "Dirt, Disgust, and Disease: Is Hygiene in Our Genes?". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 44 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1353/pbm.2001.0001. PMID 11253302.

- ^ "'Horror house' demolished but neighborhood left overrun with rats". ABC Action News Tampa Bay (WFTS). 20 December 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Curtis, Valerie A. (2007). "Dirt, disease, and disgust: A natural history of hygiene". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 61 (8): 660–664. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.062380. PMC 2652987. PMID 17630362.

- ^ Schaller, Mark; Duncan, Lesley A. (2011). "The behavioral immune system: Its evolution and social psychological implications". In Forgas, Joseph P.; Haselton, Martie G.; von Hippel, William (eds.). Evolution and the Social Mind. Psychology Press. pp. 293–307. doi:10.4324/9780203837788. ISBN 978-1-136-87298-3.

- ^ a b Pond, R. S.; DeWall, C. N.; Lambert, N. M.; Deckman, T.; Bonser, I. M.; Fincham, F. D. (2012). "Repulsed by violence: Disgust sensitivity buffers trait, behavioral, and daily aggression". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 102 (1): 175–188. doi:10.1037/a0024296. PMID 21707194.

- ^ Ritz, Thomas; Thöns, Miriam; Fahrenkrug, Saskia; Dahme, Bernhard (26 August 2005). "Airways, respiration, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia during picture viewing". Psychophysiology. 42 (5): 568–578. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00312.x. PMID 16176379.

- ^ Navarrete, Carlos David; Fessler, Daniel M.T. (July 2006). "Disease avoidance and ethnocentrism: the effects of disease vulnerability and disgust sensitivity on intergroup attitudes". Evolution and Human Behavior. 27 (4): 270–282. Bibcode:2006EHumB..27..270N. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.12.001.

- ^ Vartanian, L R (2 March 2010). "Disgust and perceived control in attitudes toward obese people". International Journal of Obesity. 34 (8): 1302–1307. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.45. PMID 20195287.

- ^ a b c d Tybur, Joshua M.; Lieberman, Debra; Griskevicius, Vladas (2009). "Microbes, mating, and morality: Individual differences in three functional domains of disgust". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 97 (1): 103–122. doi:10.1037/a0015474. PMID 19586243.

- ^ Druschel, B. A.; Sherman, M. F. (March 1999). "Disgust sensitivity as a function of the Big Five and gender". Personality and Individual Differences. 26 (4): 739–748. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00196-2.

- ^ Fleischman, Diana S.; Fessler, Daniel M.T. (February 2011). "Progesterone's effects on the psychology of disease avoidance: Support for the compensatory behavioral prophylaxis hypothesis". Hormones and Behavior. 59 (2): 271–275. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.11.014. PMID 21134378. S2CID 27607102.

- ^ Gorman, James (23 January 2012). "Disgust's Evolutionary Role Is Irresistible to Researchers". The New York Times.

- ^ Meissner, Karin; Muth, Eric R.; Herbert, Beate M. (January 2011). "Bradygastric activity of the stomach predicts disgust sensitivity and perceived disgust intensity". Biological Psychology. 86 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.014. PMID 20888886.

- ^ Schienle, Anne; Köchel, Angelika; Leutgeb, Verena (December 2011). "Frontal late positivity in dental phobia: A study on gender differences". Biological Psychology. 88 (2–3): 263–269. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.08.010. PMID 21889569.

- ^ Ward, Jamie (2006). The Student's Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-534-1.[page needed]

- ^ Rozin, Paul; Lowery, Laura; Ebert, Rhonda (1994). "Varieties of disgust faces and the structure of disgust". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 66 (5): 870–881. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.870. PMID 8014832.

- ^ Ekman, Paul; Friesen, Wallace V.; Ellsworth, Phoebe (1972). Emotion in the Human Face: Guide-lines for Research and an Integration of Findings. Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-016643-8.[page needed]

- ^ Lewis, Michael B. (August 2012). "Exploring the positive and negative implications of facial feedback". Emotion. 12 (4): 852–859. doi:10.1037/a0029275. PMID 22866886.

- ^ Kohler, Evelyne; Keysers, Christian; Umiltà, M. Alessandra; Fogassi, Leonardo; Gallese, Vittorio; Rizzolatti, Giacomo (2 August 2002). "Hearing Sounds, Understanding Actions: Action Representation in Mirror Neurons". Science. 297 (5582): 846–848. Bibcode:2002Sci...297..846K. doi:10.1126/science.1070311. PMID 12161656.

- ^ a b Sprengelmeyer, R.; Rausch, M.; Eysel, U. T.; Przuntek, H. (22 October 1998). "Neural structures associated with recognition of facial expressions of basic emotions". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1409): 1927–1931. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0522. PMC 1689486. PMID 9821359.

- ^ Hayes, Catherine J.; Stevenson, Richard J.; Coltheart, Max (January 2009). "Production of spontaneous and posed facial expressions in patients with Huntington's disease: Impaired communication of disgust". Cognition & Emotion. 23 (1): 118–134. doi:10.1080/02699930801949090.

- ^ Haidt, Jonathan; Rozin, Paul; Mccauley, Clark; Imada, Sumio (March 1997). "Body, Psyche, and Culture: The Relationship between Disgust and Morality". Psychology and Developing Societies. 9 (1): 107–131. doi:10.1177/097133369700900105.

- ^ Kollareth, D; Russell, JA (September 2017). "The English word disgust has no exact translation in Hindi or Malayalam". Cognition & Emotion. 31 (6): 1169–1180. doi:10.1080/02699931.2016.1202200. PMID 27379976. S2CID 4475125.

- ^ Olatunji, Bunmi O.; Haidt, Jonathan; McKay, Dean; David, Bieke (October 2008). "Core, animal reminder, and contamination disgust: Three kinds of disgust with distinct personality, behavioral, physiological, and clinical correlates". Journal of Research in Personality. 42 (5): 1243–1259. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.009.

- ^ Phillips, M. L.; Young, A. W.; Senior, C.; Brammer, M.; Andrew, C.; Calder, A. J.; Bullmore, E. T.; Perrett, D. I.; Rowland, D.; Williams, S. C. R.; Gray, J. A.; David, A. S. (October 1997). "A specific neural substrate for perceiving facial expressions of disgust". Nature. 389 (6650): 495–498. Bibcode:1997Natur.389..495P. doi:10.1038/39051. PMID 9333238.

- ^ a b c d e Calder, Andrew J.; et al. (2000). "Impaired recognition and experience of disgust following brain injury". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (11): 1077–1088. doi:10.1038/80586. PMID 11036262. S2CID 40182662.

- ^ Keysers, C.; Xiao, D. K.; Foldiak, P.; Perrett, D. I. (2001). "The speed of sight". Cognitive Neuroscience. 13 (1): 90–101. doi:10.1162/089892901564199. PMID 11224911. S2CID 9433619.

- ^ Adolphs, Ralph; et al. (2003). "Dissociable neural systems for recognizing emotions". Brain and Cognition. 52 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00009-5. PMID 12812805. S2CID 25826623.

- ^ Stark, R.; Zimmermann, M.; Kagerer, S.; Schienle, A.; Walter, B. (2007). "Hemodynamic brain correlates of disgust and fear ratings". NeuroImage. 37 (2): 663–673. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.005. PMID 17574869. S2CID 3355457.

- ^ Mitchell, I. J. (February 2005). "Huntington's Disease Patients Show Impaired Perception of Disgust in the Gustatory and Olfactory Modalities". Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 17 (1): 119–121. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.1.119.

- ^ Sprengelmeyer, R.; Schroeder, U.; Young, A.W.; Epplen, J.T. (January 2006). "Disgust in pre-clinical Huntington's disease: A longitudinal study". Neuropsychologia. 44 (4): 518–533. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.003. PMID 16098998.

- ^ Sprengelmeyer, Reiner; Young, Andrew W.; Calder, Andrew J.; Karnat, Anke; Lange, Herwig; Hömberg, Volker; Perrett, David I.; Rowland, Duncan (1996). "Loss of disgust". Brain. 119 (5): 1647–1665. doi:10.1093/brain/119.5.1647. PMID 8931587.

- ^ Surguladze, Simon A.; El-Hage, Wissam; Dalgleish, Tim; Radua, Joaquim; Gohier, Benedicte; Phillips, Mary L. (October 2010). "Depression is associated with increased sensitivity to signals of disgust: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 44 (14): 894–902. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.02.010. PMC 4282743. PMID 20307892.

- ^ Simpson, J.; Hillman, R.; Crawford, T.; Overton, P. G. (23 October 2010). "Self-esteem and self-disgust both mediate the relationship between dysfunctional cognitions and depressive symptoms". Motivation and Emotion. 34 (4): 399–406. doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9189-2.

- ^ Stein, D.J.; Liu, Y.; Shapira, N.A.; Goodman, W.K. (2001). "The psychobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: How important is disgust?". Current Psychiatry Reports. 3 (4): 281–287. doi:10.1007/s11920-001-0020-3. PMID 11470034. S2CID 11828609.

- ^ Shapira, Nathan A.; Liu, Yijun; He, Alex G.; Bradley, Margaret M.; Lessig, Mary C.; James, George A.; Stein, Dan J.; Lang, Peter J.; Goodman, Wayne K. (October 2003). "Brain activation by disgust-inducing pictures in obsessive-compulsive disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 54 (7): 751–756. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00003-9. PMID 14512216.

- ^ Sprengelmeyer, R.; Young, A. W.; Pundt, I.; Sprengelmeyer, A.; Calder, A. J.; Berrios, G.; Winkel, R.; Vollmoeller, W.; Kuhn, W.; Sartory, G.; Przuntek, H. (1997). "Disgust implicated in obsessive-compulsive disorder". Biological Sciences. 264 (1389): 1767–1773. Bibcode:1997RSPSB.264.1767S. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0245. PMC 1688750. PMID 9447734.

- ^ Grill, H.C.; Norgren, R. (1978a). "The taste Reactivity Test. I: Miimetic responses to gustatory stimuli in neurologically normal rats". Brain Research. 143 (2): 263–279. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(78)90568-1. PMID 630409. S2CID 4637907.

- ^ Travers, J. B.; Norgren, R. (1986). "Electromyographic analysis of the ingestion and rejection of sapid stimuli in the rat". Behavioral Neuroscience. 100 (4): 544–555. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.100.4.544. PMID 3741605.

- ^ a b Parker, Linda A.; Rana, Shadna A.; Limebeer, Cheryl L. (September 2008). "Conditioned nausea in rats: Assessment by conditioned disgust reactions, rather than conditioned taste avoidance". Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology / Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale. 62 (3): 198–209. doi:10.1037/a0012531. PMID 18778149.

- ^ Grill, H.C.; Norgren, R. (1978b). "Chronically decerebrate rats demonstrate satiation but not bait shyness". Science. 201 (4352): 267–269. Bibcode:1978Sci...201..267G. doi:10.1126/science.663655. PMID 663655.

- ^ Eckel, Lisa A.; Ossenkopp, Klaus-Peter (February 1996). "Area postrema mediates the formation of rapid, conditioned palatability shifts in lithium-treated rats". Behavioral Neuroscience. 110 (1): 202–212. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.110.1.202. PMID 8652067.

- ^ a b Flynn, F. W; Grill, H. J.; Shulkin, J.; Norgren, R. (1991). "Central gustatory lesions: II. Effects on sodium appetite, taste aversion learning, and feeding behaviors". Behavioral Neuroscience. 105 (6): 944–954. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.105.6.944. PMID 1777107.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Case, Trevor I.; Stevenson, Richard J.; Byrne, Richard W.; Hobaiter, Catherine (July 2020). "The animal origins of disgust: Reports of basic disgust in nonhuman great apes". Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. 14 (3): 231–260. doi:10.1037/ebs0000175. hdl:10023/17757. ProQuest 2229333470.

- ^ a b Sarabian, Cecile; Ngoubangoye, Barthelemy; MacIntosh, Andrew J. J. (November 2017). "Avoidance of biological contaminants through sight, smell and touch in chimpanzees". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (11): 170968. doi:10.1098/rsos.170968. PMC 5717664. PMID 29291090.

- ^ a b c d e f Cecile, Anna Sarabian (2019). Exploring the origins of disgust: Evolution of parasite avoidance behaviors in primates (Thesis). Kyoto University. doi:10.14989/doctor.k21615. hdl:2433/242653.[page needed]

- ^ Rottman, Joshua (April 2014). "Evolution, Development, and the Emergence of Disgust". Evolutionary Psychology. 12 (2): 417–433. doi:10.1177/147470491401200209. PMC 10480999. PMID 25299887.

- ^ a b Sarabian, Cecile; Belais, Raphael; MacIntosh, Andrew J. J. (4 June 2018). "Feeding decisions under contamination risk in bonobos". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1751): 20170195. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0195. PMC 6000142. PMID 29866924.

- ^ Whiten, A.; Goodall, J.; McGrew, W. C.; Nishida, T.; Reynolds, V.; Sugiyama, Y.; Tutin, C. E. G.; Wrangham, R. W.; Boesch, C. (June 1999). "Cultures in chimpanzees". Nature. 399 (6737): 682–685. Bibcode:1999Natur.399..682W. doi:10.1038/21415. PMID 10385119. S2CID 4385871.

- ^ Haidt, Jonathan; McCauley, Clark; Rozin, Paul (May 1994). "Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors". Personality and Individual Differences. 16 (5): 701–713. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7.

- ^ Krief, Sabrina; Jamart, Aliette; Hladik, Claude-Marcel (April 2004). "On the possible adaptive value of coprophagy in free-ranging chimpanzees". Primates. 45 (2): 141–145. doi:10.1007/s10329-003-0074-4. PMID 14986147.

- ^ Bertolani, Paco; Pruetz, Jill D. (12 July 2011). "Seed Reingestion in Savannah Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) at Fongoli, Senegal". International Journal of Primatology. 32 (5): 1123–1132. doi:10.1007/s10764-011-9528-5.

- ^ Hart, Benjamin L.; Hart, Lynette A. (4 June 2018). "How mammals stay healthy in nature: the evolution of behaviours to avoid parasites and pathogens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1751): 20170205. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0205. PMC 6000140. PMID 29866918.

- ^ Curtis, Valerie; de Barra, Mícheál; Aunger, Robert (12 February 2011). "Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 366 (1563): 389–401. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0117. PMC 3013466. PMID 21199843.

- ^ a b Kelly, Daniel (2011). Yuck!: The Nature and Moral Significance of Disgust. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-29484-3.[page needed]

- ^ a b Jones, Andrew; Fitness, Julie (2008). "Moral hypervigilance: The influence of disgust sensitivity in the moral domain". Emotion. 8 (5): 613–627. doi:10.1037/a0013435. PMID 18837611.

- ^ a b c Simpson, Jane; Carter, Sarah; Anthony, Susan H.; Overton, Paul G. (March 2006). "Is Disgust a Homogeneous Emotion?". Motivation and Emotion. 30 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9005-1.

- ^ Liu, Yunzhe; Lin, Wanjun; Xu, Pengfei; Zhang, Dandan; Luo, Yuejia (29 September 2015). "Neural basis of disgust perception in racial prejudice". Human Brain Mapping. 36 (12): 5275–5286. doi:10.1002/hbm.23010. PMC 6868979. PMID 26417673.

- ^ a b Vartanian, Lenny R.; Trewartha, Tara; Vanman, Eric J. (16 December 2015). "Disgust predicts prejudice and discrimination toward individuals with obesity". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 46 (6): 369–375. doi:10.1111/jasp.12370.

- ^ a b c d e f David, Bieke; Olatunji, Bunmi O. (May 2011). "The effect of disgust conditioning and disgust sensitivity on appraisals of moral transgressions". Personality and Individual Differences. 50 (7): 1142–1146. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.004.

- ^ Schnall, Simone; Haidt, Jonathan; Clore, Gerald L.; Jordan, Alexander H. (9 May 2008). "Disgust as Embodied Moral Judgment". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 34 (8): 1096–1109. doi:10.1177/0146167208317771. PMC 2562923. PMID 18505801.

- ^ Cummins, Denise Dellarosa; Cummins, Robert C. (2012). "Emotion and Deliberative Reasoning in Moral Judgment". Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 328. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00328. PMC 3433709. PMID 22973255.

- ^ May, Joshua (3 May 2013). "Does Disgust Influence Moral Judgment?". Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 92 (1): 125–141. doi:10.1080/00048402.2013.797476.

- ^ Landy, Justin F.; Goodwin, Geoffrey P. (July 2015). "Does Incidental Disgust Amplify Moral Judgment? A Meta-Analytic Review of Experimental Evidence". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 10 (4): 518–536. doi:10.1177/1745691615583128. PMID 26177951.

- ^ Ghelfi, Eric; Christopherson, Cody D.; Urry, Heather L.; Lenne, Richie L.; Legate, Nicole; Ann Fischer, Mary; Wagemans, Fieke M. A.; Wiggins, Brady; Barrett, Tamara; Bornstein, Michelle; de Haan, Bianca; Guberman, Joshua; Issa, Nada; Kim, Joan; Na, Elim; O’Brien, Justin; Paulk, Aidan; Peck, Tayler; Sashihara, Marissa; Sheelar, Karen; Song, Justin; Steinberg, Hannah; Sullivan, Dasan (March 2020). "Reexamining the Effect of Gustatory Disgust on Moral Judgment: A Multilab Direct Replication of Eskine, Kacinik, and Prinz (2011)". Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. 3 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1177/2515245919881152.

- ^ Ong, HH (2014). "Moral judgment modulation by disgust is bi-directionally moderated by individual sensitivity". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 194. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00194. PMC 3944793. PMID 24639665.

- ^ Białek, Michał; Muda, Rafał; Fugelsang, Jonathan; Friedman, Ori (2021). "Disgust and Moral Judgment: Distinguishing Between Elicitors and Feelings Matters". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 12 (3): 304–313. doi:10.1177/1948550620919569.

- ^ a b Horberg, E. J.; Oveis, Christopher; Keltner, Dacher; Cohen, Adam B. (2009). "Disgust and the moralization of purity". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 97 (6): 963–976. doi:10.1037/a0017423. PMID 19968413.

- ^ David, Bieke; Olatunji, Bunmi O. (May 2011). "The effect of disgust conditioning and disgust sensitivity on appraisals of moral transgressions". Personality and Individual Differences. 50 (7): 1142–1146. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.004.

- ^ Ahn, Woo-Young; Kishida, Kenneth T.; Gu, Xiaosi; Lohrenz, Terry; Harvey, Ann; Alford, John R.; Smith, Kevin B.; Yaffe, Gideon; Hibbing, John R.; Dayan, Peter; Montague, P. Read (November 2014). "Nonpolitical Images Evoke Neural Predictors of Political Ideology". Current Biology. 24 (22): 2693–2699. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.2693A. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.050. PMC 4245707. PMID 25447997.

- ^ Jones, Dan (30 October 2014). "Left or right-wing? Brain's disgust response tells all". New Scientist.

- ^ Smith, Kevin B; Warren, Clarisse (2020). "Physiology predicts ideology. Or does it? The current state of political psychophysiology research". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. Political Ideologies. 34: 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.01.001. S2CID 211040475.

- ^ a b c Olatunji, Bunmi O.; David, Bieke; Ciesielski, Bethany G. (2012). "Who am I to judge? Self-disgust predicts less punishment of severe transgressions". Emotion. 12 (1): 169–173. doi:10.1037/a0024074. PMID 21707158.

- ^ Overton, P. G.; Markland, F. E.; Taggart, H. S.; Bagshaw, G. L.; Simpson, J. (2008). "Self-disgust mediates the relationship between dysfunctional cognitions and depressive symptomatology". Emotion. 8 (3): 379–385. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.379. PMID 18540753.

- ^ Olatunji, Bunmi O.; Cox, Rebecca; Kim, Eun Ha (March 2015). "Self-Disgust Mediates the Associations Between Shame and Symptoms of Bulimia and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 34 (3): 239–258. doi:10.1521/jscp.2015.34.3.239.

- ^ Bektas, Sevgi; Keeler, Johanna Louise; Anderson, Lisa M.; Mutwalli, Hiba; Himmerich, Hubertus; Treasure, Janet (2022). "Disgust and Self-Disgust in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Nutrients. 14 (9): 1728. doi:10.3390/nu14091728. PMC 9102838. PMID 35565699.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Sherman, Gary D.; Haidt, Jonathan (28 June 2011). "Cuteness and Disgust: The Humanizing and Dehumanizing Effects of Emotion". Emotion Review. 3 (3): 245–251. doi:10.1177/1754073911402396.

- ^ Kupfer, Tom R.; Giner-Sorolla, Roger (15 December 2016). "Communicating Moral Motives" (PDF). Social Psychological and Personality Science. 8 (6): 632–640. doi:10.1177/1948550616679236.

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul (1992). Being and Nothingness. Translated by Barnes, Hazel Estella. Simon and Schuster. pp. 604–607. ISBN 978-0-671-86780-5.

- ^ Wilson, Robert (2007). "On Disgust: A Menippean Interview. Interview with Robert Wilson". Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/ Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée. 34 (2).

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 281.

- ^ Wilson 2002, pp. 51–52.

- ^ "Robert Plutchik's Psychoevolutionary Theory of Basic Emotions" (PDF). Adliterate.com. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ^ Jonathan Turner (1 June 2000). On the Origins of Human Emotions: A Sociological Inquiry Into the Evolution of Human Affect. Stanford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8047-6436-0.

- ^ Atifa Athar; M. Saleem Khan; Khalil Ahmed; Aiesha Ahmed; Nida Anwar (June 2011). "A Fuzzy Inference System for Synergy Estimation of Simultaneous Emotion Dynamics in Agents". International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 2 (6).

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (1991). The Emotions. University Press of America. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8191-8286-9.

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (2001). "The Nature of Emotions". American Scientist. 89 (4): 344–350. doi:10.1511/2001.28.344.

Bibliography

- Cohen, William A. and Ryan Johnson, eds. Filth: Dirt, Disgust, and Modern Life. University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

- Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Praeger, 1966.

- Kelly, Daniel. Yuck! The Nature and Moral Significance of Disgust. MIT Press, 2011.

- Korsmeyer, Carolyn (2011) Savoring Disgust: The Foul and the Fair in Aesthetics Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199842346.

- McCorkle Jr., William W. Ritualizing the Disposal of the Deceased: From Corpse to Concept. Peter Lang, 2010.

- McGinn, Colin. The Meaning of Disgust. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Menninghaus, Winfried. Disgust: Theory and History of a Strong Sensation. Tr. Howard Eiland and Joel Golb. SUNY Press, 2003

- Miller, William Ian. The Anatomy of Disgust. Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law. Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Rindisbacher, Hans J. (2005). "A Cultural History of Disgust". KulturPoetik. 5 (1): 119–127. JSTOR 40602909.

- Wilson, Robert (2007). "On Disgust: A Menippean Interview. Interview with Robert Wilson". Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/ Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée. 34 (2).

- Wilson, R. Rawdon (2002). The Hydra's Tale: Imagining Disgust. University of Alberta. ISBN 978-0-88864-368-1.

External links

- Nancy Sherman, a researcher investigating disgust

- Jon Haidt's page about the Disgust Scale

- Moral Judgment and the Social Intuitionist Model, publications by Jonathan Haidt on disgust and its relationship with moral ideas

- Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law

- Shame and Group Psychotherapy

- Turner, Leigh (March 2004). "Is repugnance wise? Visceral responses to biotechnology". Nature Biotechnology. 22 (3): 269–270. doi:10.1038/nbt0304-269. PMID 14990944.

- Purity and Pollution by Jonathan Kirkpatrick (RTF)

- Paper on the economic effects of Repugnance

- Anatomy of Disgust, Channel 4 program

- WhyFiles.org Article written about a February 2009 study in "Science" linking moral judgments with facial expressions that indicate sensory disgust.