Afar people

Qafara عفر | |

|---|---|

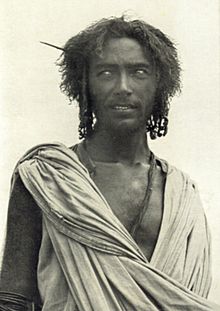

An Afar man in nomadic attire, 1950 | |

| Total population | |

| 2,708,000 (2022)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Horn of Africa | |

| 1,840,000 (2018)[1] | |

| 526,000 (2010)[2] | |

| 342,000 (2019)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Afar | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Saho, Somalis, Beja, and other Cushitic peoples[3] | |

The Afar (Afar: Qafár), also known as the Danakil, Adali and Odali, are a Cushitic ethnic group inhabiting the Horn of Africa.[4] They primarily live in the Afar Region of Ethiopia and in northern Djibouti, as well as the entire southern coast of Eritrea. The Afar speak the Afar language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family.[5] Afars are the only inhabitants of the Horn of Africa whose traditional territories border both the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.[6]

History

Early history

The earliest surviving written mention of the Afar is from the 13th-century Andalusian writer Ibn Sa'id, who reports of a people called Dankal, inhabiting an area extending from the port of Suakin to as far south as Mandeb, near Zeila.[7]

The Afar are consistently mentioned in Ethiopian records. They are first mentioned in the royal chronicles of Emperor Amda Seyon in a campaign beyond the Awash River. The Afar country was originally known in Ethiopian records as "Adal", a word that was used to denote the area of the lower Awash River to the country north of Lake Abbe, which G.W.B Huntingford describes as a "Danakil state in heavily forested region with permeant water and swamps". The chronicler describes the Afars as being "very tall with ugly faces” and that their hair was plaited like that of women so that it "reached to their waists". The chronicler was greatly impressed by their military prowess, as he states that they were "great fighters", for when they went into battle "they tied the ends of their garments, one man to the next, that they might not flee".[8]

They are again mentioned over a century later in the royal chronicles of Emperor Baeda Maryam. According to his chronicler the ruler of the Danakil offered to intervene and help in the Emperor's campaign against their neighbors, the Dobe'a. He sent the Emperor a horse, a mule laden with dates, a shield, and two spears to show his support, along with a message saying, "I have set up my camp, O my master, with the intention of stopping these people. If they are your enemies, I will not let them pass, and will seize them."[9]

According to sixteenth century Portuguese explorer Francisco Álvares, the Kingdom of Dankali was confined by Abyssinia to its west and Adal Sultanate in the east.[10]

Aussa States

Afar society has traditionally been organized into independent kingdoms, each ruled by its own Sultan. Among these were the Sultanate of Aussa, Sultanate of Girrifo, Sultanate of Dawe, Sultanate of Tadjourah, Sultanate of Rahaito, and Sultanate of Gobaad.[11] In 1577, the Adal leader Imam Muhammed Jasa moved his capital from Harar to Aussa in modern Afar region. In 1647, the rulers of the Emirate of Harar broke away to form their own polity. Harari imams continued to have a presence in the southern Afar Region until they were overthrown in the eighteenth century by the Mudaito dynasty of Afar who later established the Sultanate of Aussa.[12] The primary symbol of the Sultan was a silver baton, which was considered to have magical properties.[13]

Afar-Egyptian War

From the account given by survivors, on the 5th of October 1875, a Khedivate army divsion arrived in Tadjoura with their errands being to open up the roads between Ankober and Tadjoura, to enter into communication with King Menelik and his forces. They were also instructed to annex the Afar Sultanate of Aussa, and march further into the regions Wollo.[14] The forces consisted of 350 soldiers, 2 guns, and 45 camels. On the 14th of November upon reaching Aussa, the Egyptian forces were ambushed at night by a large number of Afar and Issa Somali warriors who managed to subdue the Egyptians, destroying their army leaving only a small number of them left fleeing to Massawa. Amongst the Egyptian casualties were the colonial invasion leader Munzinger, his wife, and his child.[15][16][17]

Conflict with Ethiopia

Ethiopia wanted to neutralize the Afar people and prevent them from helping the Italians during the course of the First Italo-Ethiopian War in 1895–1896. The show of Abyssinian force dissuaded the Afar sultan Mahammad Hanfare of the Sultanate of Aussa from honouring his treaties with Italy, and instead Hanfare secured a modicum of autonomy within the Ethiopian Empire by accepting Emperor Menelik indirect rule after the war.[18][19]

Afar Liberation Front

When a modern administrative system was introduced in Ethiopia after the Second World War, the Afar areas controlled by Ethiopia were divided into the provinces of Eritrea, Tigray, Wollo, Shewa and Hararge. Tribal leaders, elders, and religious and other dignitaries of the Afar tried unsuccessfully in the government from 1961 to end this division. Following an unsuccessful rebellion led by the Afar Sultan, Alimirah Hanfare, the Afar Liberation Front was founded in 1975 to promote the interests of the Afar people. Sultan Hanfadhe was shortly afterward exiled to Saudi Arabia. Ethiopia's then-ruling communist Derg regime later established the Autonomous Region of Assab (now called Aseb and located in Eritrea), although low-level insurrection continued until the early 1990s. In Djibouti, a similar movement simmered throughout the 1980s, eventually culminating in the Afar Insurgency in 1991. After the fall of the Derg that same year, Sultan Hanfadhe returned from exile.

In March 1993, the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Front (ARDUF) was established. It constituted a coalition of three Afar organizations: the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Union (ARDUU), founded in 1991 and led by Mohamooda Gaas (or Gaaz); the Afar Ummatah Demokrasiyyoh Focca (AUDF); and the Afar Revolutionary Forces (ARF). A political party, it aims to protect Afar interests. As of 2012, the ARDUF is part of the United Ethiopian Democratic Forces (UEDF) coalition opposition party.[20]

Demographics

Geographical distribution

The Afar principally reside in the Danakil Desert in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, as well as in Eritrea and Djibouti. They number 2,276,867 people in Ethiopia (or 2.73% of the total population), of whom 105,551 are urban inhabitants, according to the most recent census (2007).[21] The Afar make up over a third of the population of Djibouti, and are one of the nine recognized ethnic divisions (kililoch) of Ethiopia.[22]

Language

Afars speak the Afar language as a mother tongue. It is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family.

The Afar language is spoken by ethnic Afars in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, as well as in southern Eritrea and northern Djibouti. However, since the Afar are traditionally nomadic herders, Afar speakers may be found further afield.

Together, with the Saho language, Afar constitutes the Saho–Afar dialect cluster.

Society

Religion

Afar people are predominantly Muslim. They have a long association with Islam through the various local Muslim polities and practice the Sunni sect of Islam.[11] The majority of the Afar had adopted Islam by the 13th century due to the expanding influence of holy men and traders from the Arabian peninsula.[23] The Afar mainly follow the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islam. Sufi orders like the Qadiriyya are also widespread among the Afar. Afar religious life is somewhat syncretic with a blend of Islamic concepts and pre-Islamic ones such as rain sacrifices on sacred locations, divination, and folk healing.[24][25]

Culture

Socially, they are organized into clan families led by elders and two main classes: the asaimara ('reds') who are the dominant class politically, and the adoimara ('whites') who are a working class and are found in the Mabla Mountains.[26] Clans can be fluid and even include outsiders like the (Issa clan).[24]

In addition, the Afar are reputed for their martial prowess. Men traditionally carry the jile, a famous curved knife. They also have an extensive repertoire of battle songs.[11]

The Afar are mainly livestock holders, primarily raising camels but also tending to goats, sheep, and cattle. However, shrinking pastures for their livestock and environmental degradation have made some Afar instead turn to cultivation, migrant labor, and trade. The Ethiopian Afar have traditionally engaged in salt trading but recently Tigrayans have taken much of this occupation.[24]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Afar". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Afar". Ethnologue. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Joireman, Sandra F. (1997). Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development. Universal-Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 1581120001.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 6 April 2010. ISBN 9780080877754. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 6 April 2010. ISBN 9780080877754. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Fairhead, J. D., and R. W. Girdler. "A discussion on the structure and evolution of the Red Sea and the nature of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and Ethiopia rift junction-The seismicity of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Afar triangle." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 267.1181 (1970): 49–74.

- ^ Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1997), p. 61

- ^ Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands, pp. 61–67, 106f.

- ^ Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands, pp. 61–67, 106f.

- ^ Chekroun, Amélie. Le" Futuh al-Habasa": écriture de l'histoire, guerre et société dans le Bar Sa'ad ad-din [The Futuh al-Habasa: Writings on History, War and Society in the Bar Sa'ad ad-din (Ethiopia, 17th century).]. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne. p. 196.

- ^ a b c Matt Phillips, Jean-Bernard Carillet, Lonely Planet Ethiopia and Eritrea, (Lonely Planet: 2006), p. 301.

- ^ Page, Willie. Encyclopedia of africaN HISTORY andCULTURE (PDF). Facts on File inc. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Trimingham, p. 262.

- ^ Poluha, Eva (28 January 2016). Thinking Outside the Box: Essays on the History and (Under)Development of Ethiopia. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5144-2223-6.

- ^ Wylde, Modern Abyssinia, p. 25.

- ^ Britain), Royal Geographical Society (Great (1876). Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London. Edward Stanford.

- ^ Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People, second edition. London: Oxford University Press. 1965. p. 90. ISBN 0-19-285061-X.

- ^ Akyeampong, Emmanuel Kwaku; Gates, Henry Louis (2012). Dictionary of African biography vol 1–6. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780195382075.

- ^ Soule, Aramis Houmed (2018). Deux vies dans l'histoire de la Corne de l'Afrique: Les sultans 'afar Maḥammad Ḥanfaré (r. 1861–1902) & 'Ali-Miraḥ Ḥanfaré (r. 1944–2011). Centre français des études éthiopiennes. pp. 38–43. ISBN 9782821872332.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ethiopia – Political Parties, Accessed: 1-07-2006.

- ^ "Country level" Archived 16 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Table 3.1, p.73.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Miran, Jonathan (2005). "A Historical Overview of Islam in Eritrea". Die Welt des Islams. 45 (2): 177–215. doi:10.1163/1570060054307534 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. pp. 11, 12. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- ^ Brugnatelli, Vermondo. "Arab-Berber contacts in the Middle Ages and Ancient Arabic dialects: new evidence from an old Ibadite religious text." African Arabic: approaches to dialectology. Berlin: de Gruyter (2013): 271–291.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert (2003). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-447-04746-3.

References

- Mordechai Abir, The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the reunification of the Christian empire, 1769–1855 (London: Longmans, 1968).

- J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Oxford: Geoffrey Cumberlege for the University Press, 1952).

Further reading

- Jeangene Vilmer, Jean-Baptiste; Gouery, Franck (2011). Les Afars d'Éthiopie. Dans l'enfer du Danakil. ISBN 9782352701088. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013.