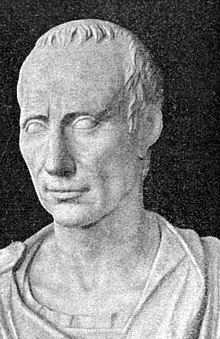

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (Latin: IMP·C·IVLIVS·CAESAR·DIVVS¹) (July 13, 100 BC – March 15, 44 BC) was a Roman military and political leader. He was instrumental in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. Caesar launched the first Roman invasion of Britain, and his conquest of Gallia Comata extended the Roman world all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, introducing Roman influence into what has become modern France, an accomplishment whose direct consequences are visible to this day.

Caesar fought and won a civil war which left him undisputed master of the Roman world, and began extensive reforms of Roman society and government. He was proclaimed dictator for life, and heavily centralized the already faltering government of the weak republic. Caesar's friend Marcus Brutus conspired with others to assasinate Caesar in hopes of saving the Republic. The dramatic assassination on the Ides of March was the catalyst for a second set of civil wars, which marked the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire under Caesar's grand-nephew and adopted son, Caesar Augustus.

Caesar's military campaigns are known in detail from his own written Commentaries (Commentarii), and many details of his life are recorded by later historians such as Suetonius, Plutarch, and Cassius Dio.

Early Life

Caesar was born in Rome to a well-known patrician family (gens Julia), which supposedly traced its ancestry to Julus, the son of the Trojan prince Aeneas, who according to myth was the son of Venus. Caesar was raised in the Subura, a lower-class neighborhood of Rome, where he apparently learned to speak several languages, including Hebrew and Gallic dialects.

The Julii Caesares, although of impeccable aristocratic patrician stock, were not rich by the standards of the Roman nobility. Thus, no member of his family had achieved any outstanding prominence in recent times, though in his father's generation there was a renaissance of their fortunes. His paternal aunt, Julia, married Gaius Marius, a talented general and reformer of the Roman army. Marius became one of the richest men in Rome at the time and while he gained political clout, the Caesar family gained the wealth.

Towards the end of Marius' life in 86 BC, internal politics reached a breaking point. Several disputes of the Marius faction against Lucius Cornelius Sulla led to civil war and eventually opened the way to Sulla's dictatorship. Caesar was tied to the Marius party through family connections. Not only was he Marius' nephew, he was also married to Cornelia Cinnilla, the youngest daughter of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Marius' greatest supporter and Sulla's enemy. To make matters worse, in the year 85 BC, just after Caesar turned 15, his father grew ill and soon died. Both Marius and his father had left Caesar much of their property and wealth in their wills.

Thus, when Sulla emerged as the winner of this civil war and began his program of proscriptions, Caesar, not yet 20 years old, was in a bad position. Sulla ordered Caesar to divorce Cornelia in 82 BC, but Caesar refused and prudently left Rome to hide. Sulla pardoned Caesar and his family and allowed him to return to Rome. In a prophetic moment, Sulla was said to comment on the dangers of letting Caesar live. According to Suetonius, the dictator in relenting on Caesar’s proscription said, "He whose life you so much desire will one day be the overthrow of the part of nobles, whose cause you have sustained with me; for in this one Caesar, you will find many a Marius."

Despite Sulla's pardon, Caesar did not remain in Rome and left for military service in Asia and Cilicia. While still in Asia Minor, Caesar was involved in several military operations. In 80 BC while still serving under Thermus, he played a pivotal role in the siege of Miletus. During the course of the battle Caesar showed such personal bravery in saving the lives of legionaries, that he was later awarded the corona civica (oak crown). The award was of the highest honor given to a non-commander, and when worn in public, even in the presence of the Roman Senate, people were forced to stand and applaud his presence.

Back in Rome in 78 BC, when Sulla died, Caesar began his political career in the Forum at Rome as an advocate, known for his oratory and ruthless prosecution of former governors notorious for extortion and corruption. The great orator Cicero even commented, "does anyone have the ability to speak better than Caesar?" Aiming at rhetorical perfection, Caesar traveled to Rhodes in 75 BC for philosophical and oratorical studies with the famous teacher Apollonius Molo.

On the way, Caesar was kidnapped by Cilician pirates in the Mediterranean Sea. When they demanded a ransom of twenty talents, he laughed at them, saying they did not know whom they had captured. Instead, he ordered them to ask for fifty. They accepted, and Caesar sent his followers to various cities to collect the ransom money. In all he was held for 38 days would often laughingly threaten to have them all crucified. True to his word, as soon as he was ransomed and released, he organized a naval force, captured the pirates and their island stronghold and put them to death by crucifixion as a warning to other pirates. However, since they had treated him well, he had their throats cut before they were crucified to lessen their suffering.

In 69 BC, Caesar became a widower after Cornelia's death trying to deliver a stillborn son. In the same year, he lost his aunt Julia, to whom he was very attached. It was untraditional for Roman women to have great public funerals, but Caesar broke tradition and gave them fine funerals. During the funerals Caesar delivered eulogy speeches from the rostra. Julia's funeral was filled with political connotations, since Caesar insisted on parading Marius's funeral mask. Although Caesar was very fond of both women (according to Suetonius), these speeches were interpreted by his political opponents as propaganda for his upcoming election for the office of quaestor.

Caesar’s Cursus Honorum

Caesar was elected quaestor by the Assembly of the People in 69 BC, at the age of 30, as stipulated in the Roman cursus honorum. He drew the lots and was assigned with a quaestorship in Hispania Ulterior, a Roman province roughly situated in modern Portugal and southern Spain. As an administrative and financial officer, the trip was largely uneventful, but it was while in Hispania that he had the famous encounter with a statue of Alexander the Great. At the temple of Hercules in Gades, it was said that he broke down and cried. When asked why he would have such a reaction, his simple response was: "Do you think I have not just cause to weep, when I consider that Alexander at my age had conquered so many nations, and I have all this time done nothing that is memorable."

Caesar was released early from his office as quaestor, and allowed to return to Rome early. Despite any personal grief over the loss of his wife, of who all accounts suggest he loved dearly, Caesar was set to remarry in 67 BC for political gain. This time, however, he chose an odd alliance. The granddaughter of Sulla, and daughter of Quintus Pompey, Pompeia was to be his next wife. Now as a member of the Senate, thanks to his election earlier as Quaestor, Caesar supported laws which were designed to grant Pompey the Great unlimited powers in dealing with Cilician Pirates in the Mediterranean. Obviously building a relationship with Rome’s great general would play into his hands later.

Between the support of the laws regarding Pompey’s command, Caesar served as the curator of the Appian Way. The maintenance of this road, which stretched from Rome to Cumae and beyond to the heel of Italy’s boot, was an important and high profile position. While it was enormously expensive on a personal basis, it gave a great deal of prestige to a young Senator, and Crassus’ support certainly made it an achievable task for Caesar. All the while, Caesar continued to pursued his judicial career until his election as curule aedile in 65 BC, along with a young rival and member of the optimate faction by name of Bibulus.

This magistrate position was the next step in the Roman cursus honorum and was a grand opportunity for the master of the public spectacle. The curule aediles were responsible for such public duties as the construction and care of temples, maintenance of public buildings, traffic, and other aspects of Rome's daily life. Perhaps most important of all, the staging of public games on state holidays and management of the Circus Maximus. Caesar indebted himself to the point of near financial ruin during this time, but enhanced his image irreversibly with the common people. Caesar ended his year as aedile in glory but in bankruptcy. His debts reached several hundred gold talents (millions of Euros in today's currency) and threatened to be an obstacle for his future career. His co‑aedile Bibulus was so unspectacular in comparison that he later commented in frustration that the entire year’s aedile ship was credited to Caesar alone, instead of both.

His success as aedile was, however, an enormous help for his election as Pontifex Maximus (high priest) in 63 BC, following the death of the previous holder Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius. This office meant a new house — the Domus Publica (public house) — in the Forum, the responsibility of all Roman religious affairs and the custody of the Vestal virgins under his roof. For Caesar, it also meant a relief of his debts. The election put Caesar in a position of considerable power, with opportunity for income. The Pontifex was elected to a lifetime term and while technically not a political office, still provided considerable advantages in dealing with the Senate and legislation.

Caesar's debut as Pontifex was however marked by a scandal. Following the death of his wife Cornelia, he had married Pompeia, a granddaughter of Sulla, in 67 BC. As the wife of the Pontifex and an important matrona, Pompeia was responsible for the organization of the Bona Dea festival in December. These rites were exclusive to women and considered very sacred. However, Publius Clodius Pulcher managed to get in the house disguised as a woman. This was absolute sacrilege and Pompeia received a letter of divorce. Caesar himself admitted that she could be innocent in the plot, but, as he said: "Caesar's wife, like the rest of Caesar's family, must be above suspicion."

63 BC was an especially difficult year, not only for Caesar, but for the Roman Republic itself. Caesar ran for, and won, the office of urban Praetor. Before he could even take office, however, the Catiline Conspiracy erupted putting Caesar in direct conflict with the optimates once again. The result was the conviction to death of five notable Roman men, Catiline's allies, without a trial. The option open was banishment, as imprisonment before trial was unheard of; if banished the men would simply have gone to take command of Catiline's armies in Etruria. The Senate deliberated on the matter, with Caesar one of the few men to speak up against the death penalty.

Towards the end of his Praetorship, Caesar was again in serious jeapardy of prosecution for his debts. Crassus came to the rescue again, paying off a quarter of his 20 million denarii balance. Eventually, by 61 BC, Caesar was finally assigned to serve as the Proconsular governor of further Spain, the province he served in as a quaestor. With this appointment, his creditors backed off, allowing that this position could be quite profitable. Leaving Rome even before he was officially to take over, Caesar was not taking chances.

Arriving in Hispania, Caesar developed a remarkable reputation as a military commander. Between 61 BC and 60 BC, he won considerable victories over the local Spanish Calaici and Lusitani tribes. During one of his victories, his men hailed him as Imperator in the field, which was a vital consideration in being eligible for a triumph back in Rome. Caesar was now faced with a terrible dilemma, though. He wanted to run for Consul for 59 BC and would have to be present within the city of Rome to do so, but he also wanted to receive the honor of a triumph. The optimates surely would use this against him, forcing him to wait outside the city, as was the custom, until they confirmed his triumph. The delay would force Caesar to miss his chance to run for Consul and he made a fateful decision. In the summer of 60 BC, Caesar entered Rome to run for the highest political office in the Roman Republic.

First Triumvirate

In 60 BC, Caesar’s decision to forego a chance at a triumph for his achievements in Spain put him in a position to run for Consul. Even though Caesar had overwhelming popularity within the citizen assemblies, he had to manipulate formidable alliances within the Senate itself in order to secure his election. Already maintaining a solid friendship with the fabulously wealthy Crassus, he approached Crassus’ rival Pompey with the concept of a coalition. Pompey had already been considerably frustrated by the inability to get land reform for his eastern veterans and Caesar brilliantly patched up any differences between the two powerful leaders. The alliance was formed in late 60 BC, and remarkably remained a secret for some time. Caesar won the election easily enough, but the Optimates managed to get Caesar’s former co-aedile Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus elected as the junior Consul..

Once in office in 59 BC, Caesar’s first order of business was to pass a law that required the public release of all debates and procedures of the Senate. Next on the agenda was the appeasement of Pompey. Unused land in parts of Italy would be restored and offered to Pompey’s veterans. Doing so would not only alleviate the problem of the unemployed mob in Rome but would satisfy Pompey and his legions. Still Cato the younger and the Optimates faction opposed the concept simply because it was Caesar’s idea. Caesar rebuked the Senate and took it directly to the people.

While speaking before the citizen assemblies, Caesar asked his co-consul Bibulus his feelings on the bill, as it was important to have the support of both standing consuls. His reply was simply to say that the bill would not be passed even if everyone else wanted it. At this point the so-called first triumvirate was made publicly known with both Pompey and Crassus voicing public approval of the measure in turn. The law carried with overwhelming public support and Bibulus retired to his home in disgrace. Bibulus spent the remainder of his Consular year trying to use religious omens to declare Caesar’s laws as null and void, in an attempt to bog down the political system. Instead, however, he simply gave Caesar complete autonomy to pass almost any proposal he wanted to. After Bibulus’ withdrawal, the year of the Consulship of Caesar and Bibulus was often referred to jokingly thereafter as the year of "Julius and Caesar".

Already secure with Crassus, by marrying the daughter of his client Piso, Caesar next strengthened his alliance with Pompey. Pompey was married to Caesar’s daughter Julia. In what seemed to be a mere political edge, the marriage blossomed into romance by all accounts. Caesar was given the Proconsulship of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, granting him the opportunity to match political victories with military glory. This five year term, unprecedented for an area that was relatively secure, was an obvious sign of Caesar’s ambition for external conquests. Caesar’s future campaigns would all be conducted at his own discretion. In an additional stroke of luck, current governor of Gallia Narbonensis died, and this province was assigned to Caesar as well.

As 59 BC came to a close, Caesar had the support of the people, along with the two most powerful men in Rome (aside from himself), and the opportunity for infinite glory in Gaul. At the age of 40, while already holding the highest office in Rome and defeating his enemies at every turn, the true greatness of his career was yet to come. Marching quickly to the relative safety of his provinces, to invoke his 5 year imperium and avoid prosecution, Caesar was about to alter the geographic landscape of the ancient world.

Gallic Wars

Julius Caesar took official command of his provinces of Illyricum, Cisalpine Gaul and Transalpine Gaul in 59 BC. Beyond the province of Transalpine Gaul was a vast land comprising modern France, called Gallia Comata, where loose confederations of Celtic tribes maintained varying relationships with Rome. For the most part, a general peace reigned between the tribes and Rome for the better part of the last century, but external pressures from Germanic tribes started unsettling the relative calm. In late 59 BC, the Germanic leader Ariovistus lead an invasion of Gaul and raided the border regions, but Caesar quelled the situation at that point by arranging an alliance with the Germans by early 58 BC.

As the campaign year of 56 BC opened, Caesar found that Gaul still wasn’t quite ready for Roman occupation. Caesar sent his generals to every corner of Gaul, quelling any form of Gallic resistance in their way. Decimus Brutus, the young future assassin of Caesar, was sent to build a fleet amongst the Veneti. The Veneti controlled the waterways with a formidable fleet of their own and were augmented by British Celts. At first the Gallic vessels outmatched the Romans, and Brutus could do little to hamper Veneti operations. Roman ingenuity took over, however, and they began using hooks launched by archers to grapple the Veneti ships to their own. Before long, the Veneti were completely defeated, and like many tribes before them, sold into slavery.

In all, dozens of tribes were forced to surrender to Roman domination and hundreds of thousands of prisons were sent back to Rome as slaves. With the defeat of the Gallic resistance, Caesar next began to focus his attention across the channel. Still, the conquest was not quite as complete as it seemed. First Caesar would have to deal with more Germanic incursions before he could cross to Britain. And despite his confidence, the Gallic tribes were not nearly as subdued as he thought. For now, though, Caesar returned to Cisalpine Gaul to attend to political matters in Rome.

An agreement was reached with Pompey and Crassus in which Caesar would have his extension on his term as proconsul of Gaul while granting Pompey and Crassus a balance of power opportunity. Pompey and Crassus were to be elected as joint Consuls for 55 BC, with Pompey receiving Spain as his province and Crassus to get Syria. With the matter resolved, Crassus and Pompey returned to Rome to stand for the elections of 55 BC. Despite bitter resistance from the Optimates, including a delay in the election, the two were eventually confirmed as Consuls. Caesar quickly returned to Gaul set into motion the first Roman invasion of Britain.

Even after an unsuccessful first invasion, Caesar succeed in invasion a second time with the largest naval invasion in history until the Invasion of Normandy. At year’s end in 55 BC, Caesar had traveled to the farthest point in the known world and held most of Gaul firmly in his hand. But not all was going Caesar’s way. In 54 BC, his only daughter, Julia Caesaris, died in childbirth, leaving both Pompey and Caesar heartbroken. And to make matters worse, Crassus had been killed in 53 BC during his ill-fated campaign in Parthia. Without Crassus or Julia, Pompey began to drift towards the Optimates faction, and relations with Caesar withered. Still away in Gaul, Caesar tried to secure Pompey's support by offering him one of his nieces in marriage, but Pompey refused. Instead, Pompey married Cornelia Metalla, the daughter of Metallus Scipio, one of Caesar's greatest enemies.

New discontent was brewing among the tribes of southern central Gaul. Among those tribes were the Arverni. Initially hesitant, a young chieftan, Vercingetorix came to forefront to rally the Gauls. Other neighboring tribes soon joined the growing revolt, especially in the absence of the legions who occupied the northern and eastern portions of Gaul. Caesar had to make haste from Cisalpine Gaul and joined his army in the late winter early spring of 52 BC, Caesar had no choice but to consolidate his forces against the formidable revolt.

Caesar followed Vercingetorix’s retreating army to the fortified town of Alesia. With an alleged army of some 80,000 men, Vercingetorix and his Gauls were in shock from Caesar’s Germanic cavalry allies and were in no condition to meet the 60,000 Romans Legionaries on the battlefield. Caesar ordered the complete circumvallation of the Alesian plateau, which would not only enclose the Gauls, but keep his large army occupied during the siege. Walls, ditches and forts of various sizes stretched the entire circle for a total length of 10 miles. In one of the most brilliant siege tactics in the history of warfare, and a testament to the skill of Roman engineering, Caesar ordered a second wall to be built on the outside of the first. This wall, nearly identical to the first in construction and type, extended as much as 15 miles around the inner wall and left enough of a gap in between to fortify the entire Roman army. First wall was designed to keep Vercingetorix in, and the second wall to keep his allies out.

A massive army was raised to defend Vercingetorix. According to Caesar, nearly 250,000 Gauls came in support of their besieged ‘King’. This force marched from the territory of the Aedui to crush the Romans between two forces larger than that of their target. Inside Alesia, however, conditions were terrible, with an estimated 180,000 people (including non-combatant women and children) running out of food and supplies.

By the time the relief force arrived, Vercingetorix and his army were in dire straights, with many of his men likely on the verge of surrender. October 2, would prove to be the final battle of Alesia. The Gauls on both sides hammered the weakness in the Roman wall. Overall, the Romans may have been outnumbered as many as 6 to 1. The battle that was once very close to the possible end of Caesar, turned into an all out rout and the Gauls outside the Roman walls were slaughtered. By the end of the battle, the Germanic cavalry would virtually wipe out the retreating Gauls, leaving only Vercingetorix on the inside. Forced back into Alesia after the defeat of his relief force, with no hope of additional reinforcements, and only with the starving remnants of his own army, Vercingetorix was forced to surrender

The defeat of Vercingetorix lead to an effective end of the Gallic Wars. The whole campaign resulted in 800 conquered cities, 300 subdued tribes, one million men sold to slavery and another three million dead in battle fields.

Civil War

The Optimates despised Caesar and his conquests and looked for every opportunity to strip him of his command. Prosecuting Caesar, whether the goal was death, exile or just a symbolic limitation of his power, would prevent his re-establishment of the populares agenda that he so masterfully instituted previously. The years 50 BC and 49 BC were pivotal because during this time frame, Caesar’s imperium, namely safety from prosecution, was set to expire. Caesar badly desired the ability to run for the Consulship in abstentia, thereby allowing him the safe transfer of protection from his Proconsular Imperium, granted by his command in Gaul, to that of the actual Consulship once again.

By this time, however, Pompey, likely the only man able to smooth things over, had clearly sided with the Optimates. His jealously over Caesar’s success and his ultimate goal of acceptance and power within the Senate took him ever further from the alliance with Caesar. Laws were passed while Pompey was Consul without colleague that forced a candidate to be present in Rome to run for office.

Caesar’s only options throughout were either to surrender willingly and face certain prosecution along the end of his career or life, or go to war. On January 1, 49 BC and the days immediately following, the Senate rejected Caesar’s final peace proposal and declared him a public enemy. Around the 10th of January 49 BC, word reached Caesar and he marched south with the 13th Legion from Ravenna towards the southern limit of Cisalpine Gaul’s border. He likely arrived around January 11, and stopped on the northern bank of the small river border, the Rubicon.

Caesar seemed to contemplate the situation understandably for some time before making his final fateful decision. He is then reported to have muttered the now infamous phrase, from the work of the poet Menander, "Alea iacta est", usually quoted as "The die is cast." The Rubicon was crossed and Caesar officially invaded the legal border from his province into Italy, thus starting the civil war. Despite having two legions to Caesar’s one, Caesar’s Gallic legions were on the move to join him so Pompey and the rest of Caesar’s opposition had little choice but to leave Rome immediately and abandon Italy to Caesar. When Caesar entered Rome, he was elected Dictator, but only served for 11 days when he left office and served as Consul instead.

Soon joined by four legions from Gaul, Caesar moved swiftly into Thessaly, incorporating the towns of the region under his control. His exhausted and poorly supplied army was able to secure new sources of food and essentially become re-energized for the continuing campaign. Caesar first faced Pompey on July 10, 48 BC at Dyrrhacium. Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat to Pompey. He decisively defeated Pompey's numerically superior army — Pompey had nearly twice the number of infantry and considerably more cavalry — at the battle of Pharsalus in an exceedingly short engagement in 48 BC.

As the battle closed, Caesar reviewed the field and was likely shaken by the effects of civil war. He claimed that 15,000 enemy soldiers were killed, including 6,000 Romans, while losing only 200 of his own men, though both numbers are likely either over or under exaggerated. Still, the sight of the field apparently had a profound effect on the new master of the Roman world. In surveying the carnage, Caesar supposedly said, "They would have it so, I, Gaius Caesar, after so much success, would be condemned had I dismissed my army."

Caesar in the East

The following the defeat at Pharsalus, the majority of the remaining Pompeian forces surrendered to Caesar, and the major part of the war was essentially over. Pompey himself fled to Egypt, where his own horrible fate awaited him. Respected as the conqueror of the east, Pompey certainly felt comfortable heading into Egypt. While waiting off-shore to receive word from the boy-king, Ptolemy XIV, Pompey was betrayed and assassinated. Stabbed in the back and decapitated, his body was burned on the shore and his head was brought to the king in order to present as a gift to Caesar. On July 24, 48 BC, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus was dead, just short of 58 years old. When Caesar arrived in pursuit of Pompey, to certainly, by all accounts, grant him a pardon and welcome him back to Rome, Ptolemy presented Caesar with Pompey’s head and his signet ring. Caesar, despite realizing Pompey’s death made him the master of Rome, was overcome with grief. Turning away from the slave who presented Pompey’s head, Caesar burst into tears at the sight of his rival, former friend, and son-in-law.

When Caesar arrived with just 4,000 men, or just under one full legion, he immediately took over the palace and presumed to secure his authority. He had two goals while in Egypt, secure grain and repayment of Egyptian debts, and also to settle the matter of who should rule the country: Cleopatra or Ptolemy. Caesar privately requested a meeting with Cleopatra in order to take stock of her before making a decision.

Cleopatra was slipped into some bed coverings and presented to Caesar as a gift. Though little is known of the actual meeting, it’s quite clear that the young queen made an enormous impression on Caesar. She was elegant and charismatic, but most of all, she had power and money, and Caesar supposed she was susceptible to manipulation. Caesar, at 52 years old and 35 years her elder, easily withstood her seduction attempts, and seduced her. He would place Cleopatra on the throne of Egypt and use her as the key to controlling the vast wealth of Egypt.

By January of 47 BC, Caesar secured the reign of Cleopatra by enforcing the will of her father Ptolemy XII with both military and political force, and married her to her younger brother Ptolemy XIV. Over the next several months, Caesar and Cleopatra went on what seemed like a honeymoon vacation along the Nile. Traveling on Cleopatra’s barge as far south as his men would let him, they toured the entire country all the way to the border of Ethiopia.

While Caesar and Cleopatra enjoyed their love affair in earnest, however, Republican forces in Spain and Africa continued to be a threat. Making matters worse, though, Pharnaces II of Pontus, son of the great Roman enemy Mithridates the Great was making incursions against neighboring provinces in the Roman east. Once again Caesar gathered his forces and marched off to face another threat.

The End of the Civil War

By the campaign season of 47 BC, Caesar left Egypt and began an overland march through the far eastern provinces. Heading towards the trouble with Pharnaces, Caesar traveled through Judaea and Syria, accepting apologies and granting pardons to those foreign kings and Roman governors who had supported Pompey. In so doing, he was also able to rebuild his war chest through the various tributes paid to him. Caesar meet King Pharnaces in the battle of Zela. His victory was so swift and so complete that he commemorated it in his triumph with the words: Veni Vidi Vici ("I came, I saw, I conquered").

Thence, in 46 BC, he proceeded to Africa to deal with the remnants of Pompey's senatorial supporters under Cato the Younger. He quickly gained a significant victory at Thapsus over the forces of Metellus Scipio, who was killed in battle, and Cato the Younger. After Cato say that his forced were defeated by Caesar, in traditional Roman fashion, he fell on his sword and committed suicide.

Despite this great loss for the Senatorial faction, Pompey's sons Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompeius, together with Titus Labienus, Caesar's former propraetorian legate (legatus propraetore) and second in command in the Gallic War, escaped to Spain, where they continued to resist Caesar’s dominance of the Roman world. Caesar arrived in Spain in late November or early December of 46 BC, with 8 legions and 8,000 cavalry of his own. Caesar’s arrival was completely unexpected by the enemy, and the surprise gave him an early advantage.

In March of 45 BC, the two armies faced off in the battle of Munda with Pompey holding the high ground. Caesar was forced to march uphill against the strong enemy position, but he was never one to shirk from a chance at open battle. As his army marched to meet Pompey, and the battle was joined, it soon became clear that this would be among the most ferociously fought battles of Caesar’s career. The exhausting battle was taking its toll and both commanders left their strategic overview positions to join their men in the ranks. Caesar himself later told friends that he had fought many times for victory, but Munda was the first time he had fought for his life. Finally after an epic struggle, Caesar’s 10th legion, under his nephew Octavian, began to make the difference.

Positioned on Caesar’s right wing, the 10th started to push back Pompey’s wing. Labienus, in command of Pompey’s cavalry, recognized the threat and broke off from the main battle with his cavalry to secure the camp, but this seemed to have dire consequences. Pompey’s men seemed to have viewed this as a general retreat by the one man who knew Caesar so well, and panic was the result. Caesar’s army overwhelmed the retreating enemy and was merciless in its zeal to end the war. Up to 30,000 men were slaughtered in the carnage, including Labienus, but Gnaeus Pompey managed to escape. Still, it would turn out to be the final major battle and victory of Caesar’s career, and one that effectively ended land based resistance.

After the Civil War

Over the next few months, Caesar mopped up in Hispania and brutally punished the people for their disloyalty. Gnaeus Pompey was later killed and his brother Sextus who garrisoned Corduba managed to flee Spain entirely. Caesar was joined by his nephew Octavian just prior to the battle of Munda, and the young man secured himself as Caesar’s heir during the campaign in Spain. He certainly learned a great deal about provincial administration from his now all-powerful uncle. It was after the battle of Munda that Caesar stopped referring to Octavian as his nephew and called him his son.

Caesar returned to Italy in September, 45 BC, and among his first tasks was to file his will, naming Octavian as his solo heir. While away, the Senate had already begun bestowing honors on Caesar. Even though Caesar had not proscribed his enemies, instead pardoned nearly every one of them, there seemed to be little open resistance to Caesar, at least publicly.

Great games and celebrations were to be held on April 21to honor Caesar’s great victory. Along with the games, Caesar was honored with the right to wear triumphal clothing, including a purple robe (reminiscent of the kings of Rome) and laurel crown, on all public occasions. A large estate was being built at Rome’s expense, and on state property, for Caesar’s exclusive use. The title of Imperator also became a legal title that he could use in his name for the rest of his life.

A statue of Caesar was placed in the temple of Quirinus with the inscription To the Invincible God. Since Quirinus was the deified likeness of the city and its founder and first King, Romulus, this act identified Caesar not only on equal terms with the gods, but with the ancient kings as well. In yet more scandalous behavior, Caesar had coins minted bearing his likeness. This was the first time in Roman history that a living Roman was featured on a coin, clearly placing him above the Roman state, and tradition.

When Caesar actually returned to Rome in October of 45 BC, he gave up his fourth Consulship (which he had held without colleague) and placed Quintus Fabius Maximus and Gaius Trebonius as suffect consuls in his stead. He celebrated a fifth triumph, this time to honor his victory in Spain. The Senate continued to encourage more honors. A temple to Libertas was to be built in his honor, and he was granted the title Liberator. They elected him Consul for life, and allowed to hold any office he wanted, including those generally reserved for Plebeians, like the Tribune. He also was given the power to appointed magistrates to all provincial duties, a process previously done by draw of lots or through the approval of the Senate. The month of his birth, Quintilis, was renamed July (Latin Julius) in his honor and his birthday, July 13, was recognized as a national holiday. Even a tribe of the people’s assembly was to be named for him. A temple and priesthood, the Flamen maior, was established and dedicated in honor of his family.

Caesar, however, did have a reform agenda and took on various subjects social ills. He passed a law that prohibited citizens between the ages of 20 and 40 from leaving Italy for more than 3 years unless on military assignment. This theoretically would help preserve the continued operation of local farms and businesses and prevent corruption abroad. If a member of the social elite did harm or killed a member of the lower class, then all the wealth of the perpetrator was to be confiscated. A general cancellation of one-fourth of all debt also greatly relieved the public and helped to endear him even further to the common population.

Caesar tightly regulated the purchase of state-subsidized grain and forbade those who could afford privately supplied grain from purchasing from the grain dole. He made plans for the distribution of land to his veterans and for the establishment of veteran colonies throughout the Roman world. Caesar ordered a complete overhaul of the Roman calendar in 46 BC, establishing a 365-day year with a leap year every fourth year (this Julian Calendar was subsequently modified by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 into the modern calendar). As a result of this reform, the year 46 BC was in fact 445 days long to bring the calendar into line.

Plutarch records that at one point, Caesar informed the Senate that he felt his honours were more in need of reduction than augmentation, but withdrew this position so as not to appear ungrateful. He was given the title Pater Patriae ("Father of the Fatherland"). He was appointed dictator a third time, and then nominated for nine consecutive one-year terms as dictator, effectually making him dictator for ten years. He was also given censorial authority as prefect of morals (praefectus morum) for three years.

At the onset of 44 BC, the honors given upon Caesar continued and the subsequent rift between he and the aristocrats deepened. He had been named Dictator Perpetuus, making him dictator for the remainder of his life . This title even began to show up on coinage bearing Caesar’s likeness, placing him above all others in Rome. Some among the population even began to refer to him as ‘Rex’ (Latin king), but Caesar refused to accept the title. But the seeds of conspiracy were beginning to grow within the Senate.

Assassination

The fear of Caesar becoming king continued when someone placed a diadem on the statue of Caesar on the Rostra. Not long after the incident with the diadem, two tribunes had citizens arrested after they called out the title ‘Rex’ to Caesar as he passed by on the streets of Rome. Caesar acted harshly. He ordered those arrested to be released, and instead took the tribunes before the Senate and had them stripped of their positions.

At the coming festival of the Lupercalia, the biggest test of the Roman people for their willingness to accept Caesar as King was to take place. On February 15, 44 BC, Caesar sat upon his gilded chair on the Rostra and watched the race. When Mark Antony ran into the forum and was raised to the Rostra by the priests attending the event. Antony produced a diadem and attempted to place it on Caesar’s head, saying "the people offer this the title of king to you through me." Caesar quickly refused being sure that the diadem didn’t touch his head. The crowd roared with approval, but Antony, undeterred attempted to place it on Caesar’s head again. Still there was no voice of support from the crowd, and Caesar rose from his chair and refused Antony again, saying, "I will not be king of Rome!" The crowd wildly endorsed Caesar’s actions.

Caesar planned to leave in April of 44 BC for campaigns in Parthia, and a secret opposition that was steadily building had to act fast. Made up mostly of men that Caesar had pardoned already, they knew their only chance to rid Rome of Caesar was to prevent him ever leaving for Parthia.

Caesar summoned the Senate to meet in the Theatrum Pompeium (built by Pompey) on the Ides of March (March 15) 44 BC. A few days before, a soothsayer had said to Caesar, "Beware the Ides of March." As the Senate convened, Caesar was attacked and stabbed to death by a group of senators who called themselves the Liberators (Liberatores); the Liberators justified their action on the grounds that they committed tyrannicide, not murder, and were preserving the Republic from Caesar's alleged monarchical ambitions. Among the assassins who locked themselves in the Temple of Jupiter were Gaius Trebonius, Decimus Junius Brutus, Marcus Junius Brutus, and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Caesar had personally pardoned most of his murderers or personally advanced their careers. Caesar sustained 23 (as much as 35 by some accounts) stab wounds, which ranged from superficial to mortal, and ironically fell at the feet of a statue of his best friend and greatest rival, Pompey the Great. Pompey had recently been deified by the Senate, some accounts report that Caesar prayed to Pompey as he lay dying. His last words have been reported as:

- Et tu, Brute? (Lat., "And (even) you, Brutus?" – from Shakespeare's play, Julius Caesar)

Caesar's death also marked, ironically, the end of the Roman Republic, for which the assassins had struck him down. The Roman middle and lower classes, with whom Caesar was immensely popular, and had been since Gaul and before, were enraged that a small group of high-browed aristocrats had killed their champion. Antony, who'd been as of late drifting from Caesar, capitalized on the grief of the Roman mob and threatened to unleash them on the Optimates, perhaps with the intent of taking control of Rome himself.

But Caesar named his grand nephew Gaius Octavius sole heir of his vast fortune, giving Octavius both the immensely powerful Caesar name and control of one of the largest amounts of money in the Republic. In addition, Gaius Octavius was also, for all intents and purposes, the son of the great Caesar, and consequently the loyalty of the Roman populace shifted from dead Caesar to living Octavius. Octavius, only aged 19 at the time of Caesar's death, proved to be ruthless and lethal, and while Antony dealt with Decius Brutus in the first round of the new civil wars, Octavius consolidated his position. A new Triumvirate was found — the Second and final one — with Octavian, Antony, and Caesar's loyal cavalry commander Lepidus as the third member. This Triumvirate deified Caesar as Divus Julius and – seeing that Caesar's clemency had resulted in his murder – brought back the horror of proscription, abandoned since Sulla, and proscribed its enemies in large numbers in order to sieze even more funds for the second civil war against Brutus and Cassius, whom Antony and Octavian defeated at Philippi.

A third civil war then broke out between Octavian on one hand and Antony and Cleopatra on the other. This final civil war, culminating in Antony and Cleopatra's defeat at Actium, resulted in the ascendancy of Octavian, who became the first Roman Emperor, under the name Caesar Augustus. In 42 BC, Caesar was formally deified as "the Divine Julius" (Divus Iulius), and Caesar Augustus henceforth became Divi filius ("Son of God").

The literary Caesar

See Literary works of Julius Caesar.

The military Caesar

See Military career of Julius Caesar.

Caesar's name

See Etymology of the name of Julius Caesar.

Caesar's marriages and offspring

- First marriage to Cornelia Cinnilla

- Julia Caesaris, married to Pompey

- a grandson, dead at several days, unnamed

- a stillborn son, unnamed

- Julia Caesaris, married to Pompey

- Second marriage to Pompeia Sulla

- Third marriage to Calpurnia Pisonis

- Affair with Cleopatra VII

- Ptolemy XV Caesar (Caesarion), Egyptian pharaoh

- Posthumously adopted son, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, Roman emperor

Chronology

- July 13 100 BC – Birth in Rome; Alternatively, July 12, 102 BC

- 84 BC – First marriage to Cornelia Cinnilla

- 82 BC – Escapes the Sullan persecutions

- 81/79 BC – Military service in Asia and Cilicia; tryst with Nicomedes of Bithynia

- 70s – Career as an advocate

- 69 BC – Death of Cornelia, Quaestor in Hispania Ulterior

- 65 BC – Curule aedile

- 63 BC – Second marriage to Pompeia Sulla,

- December, Divorces Pompeia

- Elected pontifex maximus and praetor urbanus

- the Catilinarian conspiracy

- 61 BC – Serves of Propraetor in Hispania Ulterior

- 59 BC – First consulship with Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, beginning of the First Triumvirate

- Third marriage to Calpurnia Pisonis

- 58 BC/53 BC – First term as Proconsul of Gaul

- 54 BC – Death of Julia

- 53 BC – Death of Crassus: end of the First Triumvirate

- 53 BC/48 BC — Second term as Proconsul of Gaul

- 52 BC – Battle of Alesia

- 49 BC – Crossing of the Rubicon, the civil war starts

- 48 BC – Defeats Pompey in Greece at Battle of Pharsalus, made dictator (serves for 11 days)

- Second consulship with Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus

- 47 BC – Campaign in Egypt; meets Cleopatra VII

- 46 BC – Defeats Cato and Metellus Scipio in northern Africa, third consulship with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

- Second dictatorship

- Elected Pontifex Maximus for life (introduces Julian Calendar) and adoptes Octavian as heir

- 45 BC – Defeats the last opposition in Hispania

- Returns to Rome; fourth consulship (without colleague)

- Named Pater Patriae by the Senate and third dictatorship

- 44 BC –

- Fifth consulship with Marc Antony

- Appointed perpetual dictator

- February, Refuses the diadem offered by Antony

- March 15, Assassinated

- 42 BC Formally deified as "the Divine Julius" (Divus Julius),

References

- The Gallic War, by Caesar; Loeb Classics

- Life of Caesar, by Plutarch; Oxford Classics

- The Twelve Caesars – Julius Caesar, by Suetonius; Penguin Classics

Related topics

External links

Primary sources

Caesar's own writings

- Forum Romanum Index to Caesar's works online in Latin and translation

- [1] in Latin and translation (anonymous site)

Ancient historians on Caesar

- Suetonius: The Life of Julius Caesar. (Latin and English, cross-linked: the English translation by J. C. Rolfe.)

- Suetonius: The Life of Julius Caesar (J. C. Rolfe English translation, modified)

- Plutarch: The Life of Julius Caesar (English translation)

- Cassius Dio, Books 37‑44 (English translation)

Secondary Material

- Julius Caesar Suzanne Cross's site with in‑depth history of Caesar, plus a timeline and links.

- C. Julius Caesar Jona Lendering's in‑depth history of Caesar (Livius.Org)

- Julius Caesar — virgil.org An Annotated Guide to Online Resources categorized into Primary Sources, Background & Images, Modern Essays & Historical Fiction.

- Julius Caesar, page with many links in several languages, including English

- History of Julius Caesar

Loosely Related

- All Julius Caesar Summary of Shakespeare's play, with background material on Shakespeare and Caesar.

- Forum of Caesar (Official site of the modern excavators)

Notes

1- Official name after 42 BC, Imperator Gaius Iulius Caesar Divus, in English, "Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar, the deified one". Born as Gaius Iulius Gaii Filius Gaii Nepos Caesar, in English, "Gaius Julius Caesar, son of Gaius, grandson of Gaius". Template:Lived