Trade route

Trade routes are logistical networks identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo.[1] Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial and non commercial transportation.[1]

Historically, the period from 1500 BCE-1 CE saw the Western Asian, Mediterranean, Chinese and Indian societies develop major transportation networks for trade.[2] Europe's early trading routes included the Amber Road, which served as dependable networks for long distance trade.[3] Maritime trade along the Spice route became prominent during the middle ages; nations resorted to military means for control of this influential route.[4] During the middle ages organizations such as the Hanseatic League , aimed at protecting interests of the merchants and trade, also became increasingly prominent.[5]

With the advent of modern times, commercial activity shifted from the major trade routes of the Old World to newer routes between modern nation states. This activity was sometimes carried out without traditional protection of trade and under international free trade agreements, which allowed commercial goods to cross borders with relaxed restrictions.[6] Innovative transportation of the modern times includes pipeline transport, and the relatively well known trade using rail routes, automobiles and cargo airlines.

Early trade routes

Trading networks of the Old World included the Grand Trunk Road of India and the Incense Road of Arabia.[2] The peninsula of Anatolia lay on the commercial land routes to Europe from Asia as well as the sea route from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.[7] Records from the 19th century BCE attest to the existence of an Assyrian merchant colony at Kanesh in Cappadocia (now in modern Turkey).[7] The domestication of the camel allowed Arabian nomads to control the long distance trade in spices and silk from the Far East to the Arabian Peninsula.[8] The Egyptians had trade routes through the Red sea, importing spices from the "Land of Punt" (East Africa) and from Arabia.[9]

Incense Route

The Incense Route served as a channel for trading of Indian, Arabian and East Asian goods.[10] The incense trade flourished from South Arabia to the Mediterranean between roughly the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[11] This trade was crucial to the economy of Yemen and the frankincense and myrrh trees were seen as a source of wealth by the its rulers.[12]

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, emperor of Ptolemaic Egypt, may have forged an alliance with the Lihyanites in order to secure the incense route at Dedan, thereby rerouting the incense trade from Dedan to the coast along the Red Sea to Egypt.[13] I. E. S. Edwards connects the Syro-Ephraimite War to the desire of the Israelites and the Aramaeans to control the northern end of the Incence route, which ran up from Southern Arabia and could be tapped by commanding Transjordan.[14]

Gerrha, inhabited by Chaldean exiles from Babylon, controlled the Incense trade routes across Arabia to the Mediterranean and exercised control over the trading of aromatics to Babylon in the 1st century BC.[15] The Nabateans exercised control over the routes along the Incense Route.[16] In order to release the Incense Route from the Nabatean control military expeditions were undertaken, without success, by Antigonus Cyclops, emperor of Syria and Palestine.[16] The Nabatean control over trade increased and spread in many directions.[16]

The replacement of Greece by the Roman empire as the administrator of the Mediterranean basin led to the resumption of direct trade with the East and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of the south.[17] The Romans sacked Ptolemaic Egypt and controlled trade with India.[18] The monopoly of the middlemen weakened with the development of monsoon trade, forcing the Parthian and Arabian middlemen to adjust their prices so as to compete on the Roman market with the goods now being bought in by a direct sea route to India.[17] Indian ships sailed to Egypt as the maritime routes of Southern Asia were not under the control of a single power.[17]

Silk Route

The Silk road was one of the first trade routes to join the Eastern and the Western worlds.[19] According to Vadime Elisseeff (2000):[19]

Along the Silk Roads, technology traveled, ideas were exchanged, and friendship and understanding between East and West were experienced for the first time on a large scale. Easterners were exposed to Western ideas and life-styles, and Westerners too, learned about Eastern culture and its spirituality-oriented cosmology. Buddhism as an Eastern religion received international attention through the Silk Roads.

Cultural interactions patronized often by powerful emperors, such as Kanishka, led to development of art due to introduction of a rich variety of influences.[19] Buddhist missions thrived along the Silk Roads, partly due to the conducive intermixing of trade and cultural values, which created a series of safe stoppages for both the pilgrims and the traders.[20] Among the frequented routes of the Silk Route was the Burmese route extending from Bhamo, which served as a path for Marco Polo's visit to Yunnan and Indian Buddhist missions to Canton in order to establish Buddhist monasteries.[21] This route — often under the presence of hostile tribes — also finds mention in the works of Rashid al-Din.[21]

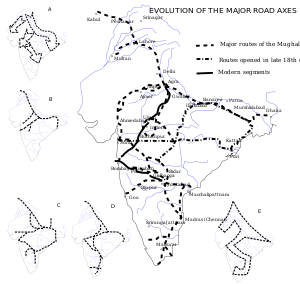

Grand Trunk Road

The Grand Trunk Road connecting Calcutta in India to Peshawar in Pakistan has existed for over two and a half millennia.[22] One of the important trade routes of the world, this road has been a strategic artery with fortresses, halting posts, wells, post offices, milestones and other facilities.[22] Part of this road through Pakistan also coincided with the Silk Road.[22]

This highway has been associated with emperors Chandragupta Maurya and Sher Shah Suri, the latter became synonymous with this route due to his role in ensuring the safety of the travelers and the upkeep of the road.[23] Emperor Sher Shah widened and realigned the road to other routes, and provided approximately 1700 roadside inns through his empire.[23] These inns provided free food and lodgings to the travelers regardless of their status.[23]

The British occupation of this road was of special significance for the British Raj in India.[24] Bridges, pathways, newer inns were constructed by the British for the first thirty seven years of their reign since the occupation of Punjab in 1849.[24] The British followed roughly the same alignment as the old routes, and at some places the newer routes ran parallel to the older routes.[24]

Vadime Elisseeff (2000) comments on the Grand Trunk Road:[25]

Along this road marched not only the mighty armies of conquerers, but also the caravans of traders, scholars, artists, and common folk. Together with people, moved ideas, languages, customs, and cultures, not just in one, but in both directions. At different meeting places— permanent as well as temporary— people of different origins and from different cultural backgrounds, professing different faiths and creeds, eating different foods, wearing different clothes, and speaking different languages and dialects would meet one another peacefully. They would understand one another's food, dress, manner, and etiquette, and even borrow words, phrases, idioms and, at times, whole languages from others.

Amber Road

The Amber Road was a European trade route associated with the trade and transport of amber.[3] Amber satisfied the criteria for long distance trade as it was light in weight and in high demand for ornamental purposes around the Mediterranean.[3] Before the establishment of Roman control over areas such as Pannonia, the Amber Road was virtually the only route available for long distance trade.[3]

Towns along the Amber Road began to rise steadily during the first century, despite the troop movements under Titus Flavius Vespasianus and his son Titus Flavius Domitianus.[26] Under the reign of Tiberius Caesar Augustus, the Amber Road was straightened and paved according to the prevailing urban standards.[27] Roman towns began to appear along the road, initially founded near the site of Celtic oppida.[27]

The third century saw the Danube river become the principal artery of trade, eclipsing the Amber Road and other commercial routes.[3] The redirection of investment to the Danubian forts saw the towns along the Amber Road growing slowly, though yet retaining their prosperity.[28] The prolonged struggle between the Romans and the barbarians further left its mark on the towns along the Amber Road.[29]

Via Maris

Via Maris, literally Latin for "the way of the sea,"[30] was an ancient highway used by the Romans and the Crusaders.[31] The states controlling the Via Maris were in a position to grant access for trade to their own citizens and collect tolls from the outsiders to maintain the trade route.[32] The name Via Maris is a Latin translation of a Hebrew phrase related to Isaiah.[31] Due to the Biblical significance many attempts have been made by the Christian pilgrims in order to locate the route, among other Biblical sites.[31] 13th century traveler and pilgrim Burchard of Mount Zion refers to the Via Maris route as a way leading along the shore of the Sea of Galilee.[31]

Spice Trade

As trade between India and the Greco-Roman world increased[33] spices became the main import from India to the Western world,[34] bypassing silk and other commodities.[35] The Indian commercial connection with South East Asia proved vital to the merchants of Arabia and Persia during the seventh century and the eighth century.[36]

The Abbasids used Alexandria, Damietta, Aden and Siraf as entry ports to India and China.[37] Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden payed tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.[37] Moluccan products shipped across the ports of Arabia to the Near East passed through the ports of India and Sri Lanka.[38] Indian exports of spices find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850), al-Ghafiqi (1150 AD), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (fourteenth century).[38] After reaching either the Indian or the Sri Lankan ports were sometimes shipped to East Africa, where they would be used for many purposes, including burial rites.[38]

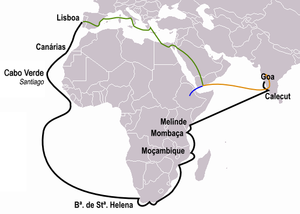

On the orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, continuing to the eastern coast of Africa to Malindi to sail across the Indian Ocean to Calicut.[39] The wealth of the Indies was now open for the Europeans to explore; the Portuguese Empire was one of the early European empires to grow from spice trade.[39]

Hanseatic trade

Shortly before the twelfth century the Germans played a relatively modest role in the north European trade.[40] With the development of Hanseatic trade German traders became prominent in the Baltic and the North Sea regions.[41] Following the death king Eric Menved, German forces attacked and sacked Denmark.[42] The new administration bought artisans and merchants with them and controlled the Hansa regions.[42] During the third quarter of the fourteenth century the Hanseatic trade faced two major difficulties: economic conflict with the Flanders and hostilities with Denmark.[5] These events led to the formation of an organized association of Hanseatic towns, which replaced the earlier union of German merchants.[5] This new Hansa of the towns, aimed at protecting interests of the merchants and trade, became prominent for the next hundred and fifty years.[5]

Philippe Dollinger associates the downfall of the Hansa to a new alliance between Lubeck, Hamburg and Bremen, which outshadowed the older institution.[43] He further sets the date of dissolution of the Hansa at 1630.[43] The Hansa was almost entirely forgotten by the end of the eighteenth century.[44] Georg Friedrich Sartorius published the first monograph regarding the community in the early years of the nineteenth century.[44]

Modern trade

The modern times saw development of newer means of transport and free trade agreements which altered the political and logistical approach prevalent during the middle ages. Newer means of transport led to the establishment of new routes, and countries opened up borders to allow trade in mutually agreed goods as per the prevailing free trade agreement. Some old trading route were reopened during the modern times, although in different political and logistical scenarios.[45]

The 1844 Railway act of England compelled at least one train to a station every day with the third class fares priced at a penny a mile.[46] Trade benefited as the workers and the lower classes had the ability to travel to other towns frequently.[47] Suburban communities began to develop and towns began to spread outwards.[47] The British constructed a vast railway network in India, but it was considered to serve a strategic purpose in addition to the commercial purpose.[48]

The modern times saw nations struggle for the control of rail routes.[49] The unification of the United States of America was helped by the efficient use of railways.[49] The Trans-Siberian Railway was intended to be used by the Russian government for control of Manchuria and later China; the German forces wanted to establish Berlin-Baghdad Railway in order to influence the Near East; and the Austrian government planned a route from Vienna to Salonika for control of the Balkans.[49]

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline connects the modern nation states of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey through a buried pipeline.[50] With a capacity to export one million barrels of oil a day, it has pump stations in all the three countries.[50] Other examples of pipeline transport include Alashankou-Dushanzi Crude Oil Pipeline and Iran-Armenia Natural Gas Pipeline.

Historically, governments followed a policy of protection of trade.[6] International Free Trade became visible in 1860 with the Anglo-French commercial treaty and the sentiment further gained momentum during the post Second World War era.[6] On May 2004, the United States of America signed the American Free trade Agreement with five Central American nations.[6]

According to The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition:[6]

After World War II, strong sentiment developed throughout the world against protection and high tariffs and in favor of freer trade. The results were new organizations and agreements on international trade such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1948), the Benelux Economic Union (1948), the European Economic Community (Common Market, 1957), the European Free Trade Association (1959), Mercosur (the Southern Cone Common Market, 1991), and the World Trade Organization (1995). In 1993 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was approved by the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. In the early 1990s the nations of the European Union (the successor organization to the Common Market) undertook to remove all barriers to the free movement of trade and employment across their mutual borders.

Express delivery through international cargo airlines touched US $ 20 billion in 1998 and, according to the World Trade Organization, is expected to triple in 2015.[51] In 1998, 50 pure cargo service companies operated internationally.[51]

Notes

- ^ a b Ciolek, T. Matthew. "Old World Trade Routes (OWTRAD) Project" (HTML). Asia Pacific Research Online.

- ^ a b Denemark 200: 274

- ^ a b c d e Burns 2003: 213

- ^ Donkin 2003: 169

- ^ a b c d Dollinger 1999: 62

- ^ a b c d e free trade. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05.

- ^ a b Stearns 2001: 37

- ^ Stearns 2001: 41

- ^ Rawlinson 2001: 11-12

- ^ "Traders of the Gold and Incense Road" (HTML). Message of the Republic of Yemen, Berlin.

- ^ "Incense Route - Desert Cities in the Negev" (HTML). UNESCO.

- ^ Glasse 2001: 59

- ^ Kitchen 1994: 46

- ^ Edwards 1969: 329

- ^ Larsen 1983: 56

- ^ a b c Eckenstein 2005: 86

- ^ a b c Lach 1994: 13

- ^ Shaw 2003: 426

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 326

- ^ Elisseeff 2000: 5

- ^ a b Elisseeff 2000: 14

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 158

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 161

- ^ a b c Elisseeff 2000: 163

- ^ Elisseeff 2000: 178

- ^ Burns 2003: 216

- ^ a b Burns 2003: 211

- ^ Burns 2003: 229

- ^ Burns 2003: 231

- ^ Orlinsky 1981: 1064

- ^ a b c d Orlinsky 1981: 1065

- ^ Silver 1983: 49

- ^ At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Ethiopia, and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise. - Strabo (II.5.12.); Source.

- ^ Ball 2000: 131

- ^ Ball 2000: 137

- ^ Donkin 2003: 59

- ^ a b Donkin 2003: 91-92

- ^ a b c Donkin 2003: 92

- ^ a b Gama, Vasco da. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Dollinger 1999: page 9

- ^ Dollinger 1999: page 42

- ^ a b Dollinger 1999: page 54

- ^ a b Dollinger 1999: page xix

- ^ a b Dollinger 1999: page xx

- ^ Historic India-China link opens (BBC)

- ^ Seaman 1973: 29-30

- ^ a b Seaman 1973: 30

- ^ Seaman 1973: 348

- ^ a b c Seaman 1973: 379

- ^ a b BP Caspian : Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline (Overview)

- ^ a b Hindley 2004: 41

References

- Stearns, Peter N. (2001-09-24). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Rawlinson, Hugh George (2001). Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times of the Fall of Rome. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120615492.

- Denemark, Robert Allen (2000). World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change. Routledge. ISBN 0415232767.

- Glasse, Cyril (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0759101906.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (1994). Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0853233594.

- Edwards, I. E. S. (1969). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521227178.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Larsen, Curtis (1983). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarcheology of an Ancient Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226469069.

- Eckenstein, Lina (June 23, 2005). A History of Sinai. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0543952150.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery. Book 1. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226467317.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192804588.

- Elisseeff, Vadime (2000). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1571812210.

- Orlinsky, Harry Meyer (1981). Israel Exploration Journal Reader. KTAV Publishing House Inc. ISBN 0870682679.

- Silver, Morris (1983). Prophets and Markets: The Political Economy of Ancient Israel. Springer. ISBN 0898381126.

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. ISBN 0415113768.

- Donkin, Robin A. (2003). Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 0871692481.

- Burns, Thomas Samuel (2003). Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.-A.D. 400. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801873061.

- Seaman, Lewis Charles Bernard (1973). Victorian England: Aspects of English and Imperial History 1837-1901. Routledge. ISBN 0415045762.

- Hindley, Brian (2004). Trade Liberalization in Aviation Services: Can the Doha Round Free Flight?. American Enterprise Institute. ISBN 0844771716.

- Dollinger, Philippe (1999). The German Hansa. Routledge. ISBN 041519072X.