Lottery

- For other articles concerned with Lotteries see Lottery (disambiguation).

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2008) |

A lottery is a popular form of gambling which involves the drawing of lots for a prize. Some governments outlaw it, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national lottery. It is common to find some degree of regulation of lottery by governments.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most forms of gambling, including lotteries and sweepstakes, were illegal in many countries, including the U.S.A. and most of Europe. This remained so until after World War II. In the 1960s casinos and lotteries began to appear throughout the world as a means to raise revenue in addition to taxes.

Lotteries are most often run by governments or local states and are sometimes described as a regressive tax, since those most likely to buy tickets will typically be the less affluent members of a society. The astronomically high odds against winning have also led to the epithets of a "tax on stupidity", "math tax" or the oxymoron "voluntary tax" (playing the lottery is voluntary; taxes are not). They are intended to suggest that lotteries, being an addictive form of gambling, are governmental revenue-raising mechanisms that will attract only those consumers who fail to see that the game is a very bad deal. Indeed, the desire of lottery operators to guarantee themselves a profit requires that an average lottery ticket be worth substantially less than what it costs to buy. After taking into account the present value of the lottery prize as a single lump sum cash payment, the impact of any taxes that might apply, and the likelihood of having to share the prize with other winners, it is not uncommon to find that a ticket for a typical major lottery is worth less than one third of its purchase price. The large multi million dollar prize lotteries in the USA are paid by annuity over 20 years. Therefore, if you take a one-time lump sum cash payment, plus pay the federal taxes, you will end up with about one third of the total prize money offered.

Lotteries come in many formats. The prize can be fixed cash or goods. In this format there is risk to the organizer if insufficient tickets are sold. The prize can be a fixed percentage of the receipts. A popular form of this is the "50-50" draw where the organizers promise that the prize will be 50% of the revenue. The prize may be guaranteed to be unique where each ticket sold has a unique number. Many recent lotteries allow purchasers to select the numbers on the lottery ticket resulting in the possibility of multiple winners.

The fact that lotteries are commonly played leads to some contradictions against standard models of economic rationality. However, the expectations of some players may not be to win the game, but to experience the thrill and indulge in a fantasy of possibly becoming wealthy. Even ignoring the thrill factor, there is the theoretical possibility that the purchase of a lottery ticket could represent a gain in expected utility, even though it represents a loss in expected monetary value, thus making the purchase a rational decision. Insurance, for instance, represents negative expected monetary value but is not considered to be a tax on stupidity because it is generally believed to deliver positive expected utility to the individual.

What motivates so many people to buy lottery tickets? Alexander Hamilton expressed the opinion that most people are willing to wager a little amount with a chance to win a large amount...and that they prefer a small chance of winning a great amount instead of a great chance to win a small amount. Simply put, it costs little to dream big, and you can't win if you don't play.

Lottery tickets are usually scanned in large numbers, using marksense-technology. With today's computer performance, it takes less than one second to check if a particular combination was picked up by anyone, even for lotteries like Euromillions or MegaMillions.

Early history

The first signs of a lottery trace back the Han Dynasty between 205 and 187 B.C., where ancient Keno slips were discovered. The lottery has helped finance major governmental projects like the Great Wall of China. From the Chinese "The Book of Songs" (second millennium B.C.) comes a reference to a game of chance as "the drawing of wood", which in context appears to describe the drawing of lots. From the Celtic era, the Cornish words "teulet pren" translates into "to throw wood" and means "to draw lots". The Iliad by Homer refers to lots being placed into Agamemon's helmet to determine who would fight Hector.

The first known European lottery occurred during the Roman Empire, and was mainly done as a form of amusement at dinner parties. Each guest would receive a ticket, and prizes would often consist of fancy items such as dinnerware. Every ticket holder would be assured of winning something. This type of lottery however, was no more than the distribution of gifts by wealthy noblemen during the Saturnalian revelries. The earliest records of a lottery offering tickets for sale is the lottery organized by Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar. The funds were for repairs to the City of Rome, and the winners were given prizes in the form of articles of unequal value.

The earliest public lottery on record is that which was held in the Dutch town of Sluis in 1434.

The first recorded lotteries to offer tickets for sale with prizes in the form of money were held in the Low Countries during the period 1443-1449. Various towns in Flanders (parts of Belgium, Holland, and France), held public lotteries to raise money for town fortifications, and raising money to help the poor. The town records of Ghent, Utrecht, and Bruges, indicate that the lotteries may well be of even greater antiquity. An early record dated May 9,1445 at L'Ecluse, refers to raising funds to build walls and town fortifications, with a lottery of 4,304 tickets and total prize money of 1737 florins.[1] In the seventeenth century it was quite normal in The Netherlands to organize lotteries in order to collect money for the poor. Tickets cost about four guilders and the prizes were paintings (50 to 100 per lottery); some of these the paintings were produced by nowadays famous painters as Jan van Goyen.

The Dutch were the first to shift the lottery to solely money prizes and base prizes on odds (roughly about 1 in 4 tickets winning a prize). The lottery proved to be very popular, and was hailed as a painless form of taxation. In the Netherlands the lottery was used to raise money for e.g. supporting poor people, building dikes, construction of defense works for towns and to buy free sailors from slavery in the Arab countries. The English word lottery stems from the Dutch word loterij, which is derived from the Dutch noun lot meaning fate. The Dutch state owned staatsloterij is the oldest still existing lottery.

English lotteries, 1566-1826

Although it is more than likely that the English first experimented with raffles and similar games of chance, the first recorded official lottery was chartered by Queen Elizabeth I, in the year 1566, and was drawn in 1569. This lottery was designed to raise money for the "reparation of the havens and strength of the Realme, and towardes such other publique good workes." Each ticket holder won a prize, and the total value of the prizes equaled the money raised. Prizes were in the form of silver plate and other valuable commodities. The lottery was promoted by scrolls posted throughout the country showing sketches of the prizes. [2]

Thus, the lottery money received was a loan to the government during the three years that the tickets ('without any Blankes') were sold. In later years, the government sold the lottery ticket rights to brokers, who in turn hired agents and runners to sell them. These brokers eventually became the modern day stockbrokers for various commercial ventures.

Most people could not afford the entire cost of a lottery ticket, so the brokers would sell shares in a ticket; this resulted in tickets being issued with a notation such as "Sixteenth" or "Third Class."

Many private lotteries were held, including raising money for The Virginia Company of London to support its settlement in America at Jamestown. The English State Lottery ran from 1694 until 1826. Thus, the English lotteries ran for over two hundred and fifty years, until the government under constant pressure from the opposition in parliament declared a final lottery in 1826. This lottery was held up to ridicule by contemporary commentators as "the last struggle of the speculators on public credulity for popularity to their last dying lottery."

Colonial & Early America Lotteries, 1612-1900

An English lottery authorized by King James I in 1612, granted the Virginia Company of London the right to raise money to help establish settlers in the first permanent English colony at Jamestown, Virginia.

Lotteries in colonial America played a significant part in the financing of both private and public ventures. It has been recorded that more than two hundred lotteries were sanctioned between 1744 and 1776 where they played a major role in financing projects that included roads, libraries, churches, colleges, canals, bridges, etc.[3] In the 1740s, Princeton and Columbia University had their beginnings financed by lotteries, as did the University of Pennsylvania by the Academy Lottery in 1755.

During the French and Indian Wars, several colonies used lotteries to supplement the cost of building fortifications and supporting their local militia. In May 1758, the State of Massachusetts raised money with a lottery for the "Expedition against Canada."

Benjamin Franklin organized a lottery to raise money to purchase cannon for the defense of Philadelphia. Several of these lotteries offered prizes in the form of "Pieces of Eight." George Washington's Mountain Road Lottery was unsuccessful in 1768. However, these rare lottery tickets bearing George Washington's signature have become collector's items which sell for about $15,000 in 2007. Later, in 1769, Washington was a manager for Col. Bernard Moore's "Slave Lottery" whereby land and slaves were advertised as prizes in the Virginia Gazette.

At the outset of the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress used lotteries to raise money to support the Colonial Army. Alexander Hamilton wrote that lotteries should be kept simple, and that, "Everybody...will be willing to hazard a trifling sum for the chance of considerable gain...and would prefer a small chance of winning a great deal to a great chance of winning little." Taxes had never been accepted as a way to raise public funding for projects, and this led to the popular belief that lotteries were a form of a hidden tax.

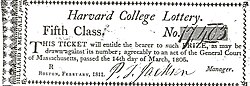

At the end of the Revolutionary War the various states had to resort to lotteries to raise funds for numerous public projects. For many years these lotteries were highly successful and contributed to the nation's rapid growth. The lotteries were used for such diverse projects as the Pennsylvania Schuylkill - Susquehanna Canal (lottery in May, 1795), and Harvard College (lottery in March, 1806). Many American churches raised needed building funds through state authorized private lotteries.

However, they eventually became a source of financial mismanagement and scandal. Most notorious of the lotteries was the Louisiana State Lottery (1868-1892) which was aptly called the "Golden Octopus" because its tentacles reached into every home in America.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century a large majority of state constitutions banned lotteries. Finally, on July 29, 1890, U.S. President Benjamin Harrison sent a message to Congress demanding "severe and effective legislation" against lotteries. Congress acted swiftly, and banned the U.S. mails from carrying lottery tickets. The Supreme Court upheld the law in 1892, and that brought a complete halt to all lotteries in the U.S.A. by 1900.

When lotteries raised their head again in 1964, it would take many years of constitutional amendements by the various states before the lotteries were allowed to flourish again...and flourish they did.

On March 12, 1964, New Hampshire became the first state to sell lottery tickets in the modern era.

For modern USA lotteries visit: Lotteries in the United States

Countries with a national lottery

Americas

- Argentina: Quiniela, Loto and various others.

- Barbados: Barbados lottery and various others.

- Brazil: Mega-Sena and various others

- Canada: Lotto 6/49 and Lotto Super 7

- Dominican Republic: Lotería Electrónica Internacional Dominicana S.A.

- Ecuador: Lotería Nacional

- Mexico: Lotería Nacional para la Asistencia Pública

- Mexico: Pronósticos para la Asistencia Pública

Europe

- Pan-European: "Euro Millions"

- Nordic countries: Viking Lotto

- Austria: Lotto 6 aus 45, "Euro Millions" and Zahlenlotto

- Belgium: Loterie Nationale or Nationale Loterij and "Euro Millions"

- Bulgaria: TOTO 2 6/49

- Croatia: Hrvatska lutrija

- Denmark: Lotto, Klasselotteriet

- Finland: Lotto

- France: La Française des Jeux and "Euro Millions"

- Germany: Lotto 6 aus 49 and Spiel 77 and Super 6

- Greece: Lotto 6/49 , Joker 5/45 + 1/20 and various others

- Hungary: Lottó

- Iceland: Lottó

- Ireland: The National Lottery, An Chrannchur Náisiúnta and "Euro Millions"

- Italy: Lotto, "Superenalotto"

- Latvia: Latloto 5/35, SuperBingo, Keno. Visit: [1]

- Luxembourg: "Euro Millions"

- Malta: Super 5 (Every Wednesday), Lotto (Lottu in Maltese) (Every Saturday)

- Montenegro: Lutrija Crne Gore

- Netherlands: Staatsloterij

- Norway: Lotto

- Poland: Lotto

- Portugal: Lotaria Clássica, "Euro Millions" and Lotaria Popular

- Romania: Loteria Romana - 6/49, 5/40, Pronosport

- Russia: Sportloto

- Serbia: Drzavna lutrija Srbije

- Slovakia: Tipos, národná lotériová spoločnosť, a.s. operating Loto, Joker, Loto 5 z 35, Euromilióny and various others

- Slovenia: Loterija Slovenije

- Spain: Loterías y Apuestas del Estado and "Euro Millions"

- Sweden: Lotto svenskaspel.se

- Switzerland: Swiss Lotto and "Euro Millions"

- Turkey: Various games by Milli Piyango İdaresi (National Lottery Administration) including Loto 6/49 and jackpots

- United Kingdom: The National Lottery, the main game being Lotto. Also Monday - The Charities Lottery, launched on May 8, 2006.[2] and "Euro Millions"

Asia

- Hong Kong: Mark Six

- Israel: "Lotto"

- Japan: Takarakuji

- Lebanon: "La Libanaise des Jeux"

- Malaysia: Sports Toto, Magnum and Magnum 4D, Pan Malaysian Pools (da ma chai)

- Philippines: Philippine Lotto Draw

- Singapore: TOTO, 4D

- South Korea: Lotto

- Taiwan: Taiwan Lottery[3]

- Thailand: สลากกินแบ่งรัฐบาล (salak gin bang ratthabarn or "Government Lottery"), also called lottery or หวย (huay).

Africa

- South Africa: South African National Lottery

- Kenya :Toto 6/49, Kenya Charity Sweepstake,

Australia

Country lottery details

In several countries, lotteries are legalized by the governments themselves. In addition, with the explosion of the internet, several online web-only lotteries and traditional lotteries with online payments have surfaced. In the web-only lotteries, the user has to select his pick and either watch an ad for a few seconds before his pick is confirmed or has to click on a web banner/link to register his pick in the system. The numbers may be drawn by the site that runs the online lotto or might be linked to a major physical lotto draw to ensure reliability. Prize money ranges from $100,000 to $10 million.

Lottery in the United States

In the United States, the existence of lotteries is subject to the laws of each state; there is no national lottery.

Private lotteries were legal in the United States in the early 1800s.[4] In fact, a number of US patents were granted on new types of lotteries. In today's vernacular, these would be considered business method patents.

Before the advent of state-sponsored lotteries, many illegal lotteries thrived; for example, see Numbers game and Peter H. Matthews. The first modern state lottery in the U.S. was established in the state of New Hampshire in 1964; as of 2008, lotteries are established in 42 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands.

The first modern interstate lottery in the U.S. was formed in 1985 and linked three of the New England states. In 1988, the Multi-State Lottery Association (MUSL) was formed with Oregon, Iowa, Kansas, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Missouri, and the District of Columbia as its charter members; it is best known for its "Powerball" drawing, which is designed to build up very large jackpots. Another interstate lottery, The Big Game (now called Mega Millions), was formed in 1996 by the states of Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan and Virginia as its charter members. These states were joined by New Jersey (1999), New York and Ohio (May 2002), Washington state (September 2002), Texas (2003) and California (2005) for a total of 12 members. [4]

Instant lottery tickets, also known as scratch cards, were first introduced in the 1970s and have since become a major source of state lottery revenue. Some states have introduced keno and video lottery terminals (slot machines in all but name).

Other interstate lotteries include Cashola, Hot Lotto and Wild Card 2, some of MUSL's other games.

With the advent of the Internet it became possible for people to play lottery-style games on-line, many times for free (the cost of the ticket being supplemented by merely seeing, say, a pop-up ad). Three of the many websites which offer free games (after registration) include iwinweekly.com, GuessLotto.com and the larger iWon.com, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of IAC Search & Media. GTech Corporation, in the United States, administers 70% of the worldwide online and instant lottery business, according to its website. With online gaming rules generally prohibitive, "lottery" games face less scrutiny. This is leading to the increase in web sites offering lottery ticket purchasing services, charging premiums on base lottery prices. The legality of such services falls into question across many jurisdictions, especially throughout the United States, as the gambling laws related to lottery play generally have not kept pace with the spread of technology.

The most recent evolution of the lottery on the internet has appeared on the social network Facebook. The free lottery has weekly drawings and allows people to receive daily lottery tickets and send their friends tickets.

Presently, many state lotteries in the USA donate large portions of their proceeds to the public education system. However these funds frequently replace instead of supplement conventional funding, resulting in no additional money for education.

Lottery in Canada

In Canada prior to 1967 buying a ticket on the Irish Sweepstakes was illegal. In that year the federal Liberal government introduced a special law (an Omnibus Bill) intended to bring up-to-date a number of obsolete laws. The Minister of Justice at that time, Pierre-Elliot Trudeau, sponsored the bill. On September 12, 1967, Mr. Trudeau announced that his government would insert an amendment concerning lotteries.

Even while the Omnibus Bill was still being written, Mayor Jean Drapeau of Montreal, trying to recover some of the money spent on the World’s Fair and the new subway system, announced a "voluntary tax". For a $2.00 donation you would be eligible to participate in a draw with a grand prize of $100 000. According to Mayor Drapeau, this "tax" was not a lottery for two reasons. The prizes were given out in the form of silver bars, not money, and the "competitors" chosen in a drawing would have to reply correctly to four questions about Montreal during a second draw. That competition would determine the value of the prize that the winner would win. The replies to the questions were printed on the back of the ticket and therefore the questions would not cause any undue problems. The inaugural draw was held on May 27, 1968.

There were debates in Ottawa and Quebec City about the legality of this 'voluntary tax'. The Minister of Justice alleged it was a lottery. Montreal’s mayor replied that it did not contravene the federal law. While everyone awaited the verdict, the monthly draws went off without a hitch. Players from all over Canada, the United States, Europe, and Asia participated.

On September 14, 1968 the Quebec Appeal Court declared Mayor Drapeau’s "voluntary tax" illegal. However, the municipal authorities did not give up the struggle. The Council announced in November that the City would appeal this decision to the Supreme Court.

As the debate over legalities continued, sales dropped significantly, because many people did not want to participate in anything illegal. Despite offers of new prizes the revenue continued to drop monthly, and by the nineteenth and final draw, was only a little over $800 000.

On December 23, 1969 an amendment was made to the Canadian Criminal Code allowing a provincial government to legally operate lottery systems.

The first provincial lottery in Canada was Quebec's Inter-Loto in 1970. Other provinces and regions introduced their own lotteries through the 1970s, and the federal government ran Loto Canada (originally the Olympic Lottery) for several years starting in the late 1970s to help recoup the expenses of the 1976 Summer Olympics. Lottery wins are generally not subject to Canadian tax, but may be taxable in other jurisdictions, depending on the residency of the winner.[5]

Today, Canada has two nation-wide lotteries: Lotto 6/49, and Lotto Super 7 (which started in 1994). These games are administered by the Interprovincial Lottery Corporation, which is a consortium of the five regional lottery commissions, all of which are owned by their respective provincial and territorial governments:

- Atlantic Lottery Corporation (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador)

- Loto-Québec (Quebec)

- Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation (Ontario)

- Western Canada Lottery Corporation (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Yukon Territory, Northwest Territories, Nunavut)

- British Columbia Lottery Corporation (British Columbia)

Lottery in France

The first known lottery in France was created by King Francis I in or around 1505. After that first attempt, lotteries were forbidden for two centuries. They reappeared at the end of the 17th century, as a "public lottery" for the Paris municipality (called Loterie de L'Hotel de Ville) and as "private" ones for religious orders, mostly for nuns in convents.

Lotteries quickly became one of the most important resources for religious congregations in the 18th century, and helped to build or rebuild about 15 churches in Paris, including St. Sulpice and Le Panthéon. At the beginning of the century, the King avoided having to fund religious orders by giving them the right to run lotteries, but the amounts generated became so large that the second part of the century turned into a struggle between the monarchy and the Church for control of the lotteries. In 1774, the monarchy--specifically Madame de Pompadour--founded the Loterie de L'École Militaire to buy what is called today the Champ de Mars in Paris, and build a military academy that Napoleon Bonaparte would later attend; they also banned all other lotteries, with 3 or 4 minor exceptions. This lottery became known a few years later as the Loterie Royale de France. Just before the French Revolution in 1789, the revenues from La Lotterie Royale de France were equivalent to between 5 and 7% of total French revenues.

Throughout the 18th century, philosophers like Voltaire as well as some bishops complained that lotteries exploit the poor. This subject has generated much oral and written debate over the morality of the lottery. All lotteries (including state lotteries) were frowned upon by idealists of the French Revolution, who viewed them as a method used by the rich for cheating the poor out of their wages.

The Lottery reappeared again in 1936, called loto, when socialists needed to increase state revenue. Since that time, La Française des Jeux (government owned) has had a monopoly on most of the games in France, including the lotteries. There have also been reports of lotteries regarding the mass guillotine executions in France. It has been said that a number was attached to the head of each person to be executed and then after all the executions, the executioner would pull out one head and the people with the number that matched the one on the head were awarded prizes (usually small ones); each number was 3-to-5 digits long.

Lottery in New Zealand

Lotteries in New Zealand are controlled by the New Zealand government. A state owned trading organisation, the New Zealand Lotteries Commission, operates low prize scratch ticket games and Powerball type lotteries with weekly prize jackpots. Lottery profits are distributed by The New Zealand Lottery Grants Board's directly to charities and community organisations. Sport and Recreation New Zealand, Creative New Zealand, and the New Zealand Film Commission are statutory bodies that operate autonomously in distributing their allocations from the Lottery Grants Board.

The lotteries are drawn on Saturday and Wednesday. Lotto is sold via a network of computer terminals in shopping centers across the nation. The Lotto game was first played in 1987 and replaced New Zealand's original national lotteries, the Art Union and the Golden Kiwi. Lotto is a pick 6 from 40 numbers game. The odds of winning the first division prize of around NZ$300,000 to NZ$2 million are 1 in 3,838,380.

The Powerball game is the standard pick 6 from 40 Lotto numbers with an additional pick 1 from 10 Powerball number. This game has odds of 1 in 30,707,040 and a first prize of between NZ$1million and NZ$15million. In 2007 Powerball changed to a pick 1 of 10 game (formerly pick 1 of 8)and the minimum Powerball prize increased from $1 million to $2 million. Big Wednesday is a game played by picking 6 numbers from 45 plus heads or tails from a coin toss. A jackpot cash prize of NZ$1million to NZ$15 million is supplemented with product prizes such as Porsche and Aston Martin cars, boats, holiday homes and luxury travel. The odds of winning first prize are 1 in 16,290,120. Results services for these games can be found at NZ Lotto Results.

Probability of winning

The chances of winning a lottery jackpot are principally determined by several factors: the count of possible numbers, the count of winning numbers drawn, whether or not order is significant and whether drawn numbers are returned for the possibility of further drawing.

In a typical 6 from 49 lotto, 6 numbers are drawn from 49 and if the 6 numbers on a ticket match the numbers drawn, the ticket holder is a jackpot winner - this is true regardless of the order in which the numbers are drawn. The odds of being the jackpot winner are approximately 1 in 14 million (13,983,816 to be exact). The derivation of this result (and other winning scores) is shown in the Lottery mathematics article. To put these odds in context, suppose one buys one lottery ticket per week. 13,983,816 weeks is roughly 269,000 years; In the quarter-million years of play, one would only expect to win the jackpot once.

The odds of winning any actual lottery can vary widely depending on lottery design. Mega Millions is a very popular multi-state lottery in the United States which is known for jackpots that grow very large from time to time. This attractive feature is made possible simply by designing the game to be extremely difficult to win: 1 chance in 175,711,536. That's over twelve times higher than the example above. Mega Millions players also pick six numbers, but two different "bags" are used. The first five numbers come from one bag that contains numbers from 1 to 56. The sixth number -- the "Mega Ball number" -- comes from the second bag, which contains numbers from 1 to 46. To win a Mega Millions jackpot, a player's five regular numbers must match the five regular numbers drawn and the Mega Ball number must match the Mega Ball number drawn. In other words, it is not good enough to pick 10, 18, 25, 33, 42 / 7 when the drawing is 7, 10, 25, 33, 42 / 18. Even though the player picked all the right numbers, the Mega Ball number at the end of the ticket doesn't match the one drawn, so the ticket would be credited with matching only four numbers (10, 25, 33, 42).

The SuperEnalotto of Italy is supposedly the most difficult where players try to match 6 numbers out of 90. The odds in making the jackpot: 1 in 622,614,630.

Most lotteries give lesser prizes for matching just some of the winning numbers. The Mega Millions game is an extreme case, giving a very small payout (US$2) even if a player matches only the Mega Ball number at the end of your ticket. Matching more numbers, the payout goes up. Although none of these additional prizes affect the chances of winning the jackpot, they do improve the odds of winning something and therefore add a little to the value of the ticket. In most lotteries, if a large amount of smaller prizes are awarded, the jackpot will be reduced, in a similar manner that the jackpot is divided if multiple players have tickets with all the winning numbers.

In the UK National Lottery the smallest prize is £10 for matching three balls. There exists a Wheeling Challenge to create the smallest set of tickets to cover enough combinations to ensure that any 6 numbers drawn will match against at least 3 numbers on at least one of the tickets. The current record is 163 tickets.

The expected value of lottery bets is often notably bad. In the United States, an expected value of 50% of the purchase price is common. For instance, when the player buys a lottery ticket for, say, $10 he obtains a financial asset with an expected value of only $5. Hence, buying a lottery ticket reduces the buyer's expected net worth. This is in contrast with financial securities like stocks and bonds whose prices are theoretically based on their expected real values, as expected by the markets at any given point in time.

In a famous occurrence, a Polish-Irish businessman named Stefan Klincewicz bought up almost all of the 1,947,792 combinations available on the Irish lottery. He and his associates paid less than one million Irish pounds while the jackpot stood at £1.7 million. There were three winning tickets, but with the "Match 4" and "Match 5" prizes, Klincewicz made a small profit overall.

Notable prizes

| Prize | Lottery | Country | Name | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $390m | Mega Millions | United States | Won by one ticket holder from New Jersey and one from Georgia | 6 March 2007 | World's largest jackpot |

| $365m | Powerball | United States | One ticket bought jointly by eight co-workers at a Nebraska meat processing plant | 18 February 2006 | World's largest single winner |

| $363m | The Big Game | United States | Two winning tickets: Larry and Nancy Ross (Michigan), Joe and Sue Kainz (Illinois) | 9 May 2000 | The Big Game is now named Mega Millions |

| €180m | EuroMillions | France(2), Portugal(1) | Three ticket holders | 3 February 2006 | Europe's largest jackpot |

| €115m | EuroMillions | Ireland | Dolores McNamara | 29 July 2005 | Europe's largest single winner and the world's largest single payout. |

| €71.8m | SuperEnalotto | Italy | One ticket bought jointly by ten bar customers in Milan | 4 May 2005 | Largest Italian prize |

| £42m | National Lottery | United Kingdom | Three ticket holders | 6 January 1996 | Largest UK prize |

| £35.4m | EuroMillions | UK | Angela Kelly, 40, East Kilbride, South Lanarkshire [6] | 10 August 2007 | Largest UK single winner |

| €37.6m | National Lottery | Germany | Won by a nurse from North Rhine-Westphalia | 7 October 2006 | Largest German prize and single winner |

| €16.2 m | National Lottery | Ireland | Paul and Helen Cunningham | 28 July 2007 | Biggest single winner and jackpot (Ireland) |

Sources:

http://www.usamega.com/archive-052000.htm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4746057.stm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4676172.stm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/4740982.stm

http://www.sisal.it/se/se_main/1,4136,se_Record_Default,00.html

On 20 September 2005 a primary school boy in Italy won £27.6 million in the national lottery. Although children are not allowed to gamble under Italian law, children are allowed to play the lottery. [7]

Payment of prizes

Winnings are not necessarily paid out in a lump sum, contrary to the expectation of many lottery participants. In certain countries, such as the USA, the winner gets to choose between an annuity payment and a one-time payment. The one-time payment is much smaller, indeed often only half, of the advertised lottery jackpot, even before applying any withholding tax to which the prize may be subject. The annuity option provides regular payments over a period that may range from 10 to 40 years.

In some online lotteries, the annual payments can be as little as $25,000 over 40 years, with a balloon payment in the final year. This type of installment payment is often made through investment in government-backed securities. Online lotteries pay the winners through their insurance backup. However, many winners choose to take the lump-sum payment, since they believe they can get a better rate of return on their investment elsewhere.

In some countries, lottery winnings are not subject to personal income tax, so there are no tax consequences to consider in choosing a payment option. In Canada, Australia, Ireland, and the United Kingdom all prizes are immediately paid out as one lump sum, tax-free to the winner.

In the United States, federal courts have consistently held that a lump sum payments received from third parties in exchange for the rights to lottery annuities are not capital assets for tax purpose. Rather, the lump sum is subject to ordinary income tax treatment.

Scams and frauds

This section possibly contains original research. (September 2007) |

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (March 2008) |

Template:Globalize/US Lottery, like any form of gambling, is susceptible to fraud, despite the high degree of scrutiny claimed by the organizers. One method involved is to tamper with the machine used for the number selection. By rigging a machine, it is theoretically easy to win a lottery. This act is often done in connivance with an employee of the lottery firm. Methods used vary; loaded balls where select balls are made to pop-up making it either lighter or heavier than the rest. All balls should be independantly verified for materials, size, pressure, susceptibility to magnetism, and other qualities.

The most infamous case of insider lottery fraud was in Pennsylvania in 1980. The Pennsylvania lottery determined its winner by an air blower, where three numbers would bubble up. By injecting fluid into every ball except those numbered 4 and 6, and then buying tickets with every combination of 4 and 6, lottery personnel guaranteed themselves big winnings. On a game that is based on the basis of get rich quick, those on the inside can be tempted to cash in on the winnings themselves.

In some US States, such as Kansas and Minnesota, losing lottery tickets can be mailed in for a raffle of special prizes. The trouble with that is that employees of stores that sell lottery tickets sometimes collect the lottery tickets that are thrown away and send them in. As a lottery official put it "The retailers have an unlimited supply of free tickets. You do not need to be an FBI agent to realize that is a tremendously unfair advantage." [5]

Some advance fee fraud scams on the Internet are based on lotteries. The fraud starts with spam congratulating the recipient on their recent lottery win. The email explains that in order to release funds the email recipient must part with a certain amount (as tax/fees) as per the rules or risk forfeiture.

Another form of lottery scam involves the selling of "systems" which purport to improve a player's chances of selecting the winning numbers in a Lotto game. These scams are generally based on the buyer's (and perhaps the seller's) misunderstanding of probability and random numbers. Sale of these systems or software is legal, however, since they mention that the product cannot guarantee a win, let alone a jackpot.

See also

- Combinadic

- Factorial

- Gambling

- GTech Corporation

- Keno

- Luck

- Probability

- Probability theory

- Betting pool

- Free lottery

- E-Lottery

References

- ^ Ron Shelley,The Lottery Encyclopedia(1986)

- ^ John Ashton, A History of English Lotteries, 1893.

- ^ John Samuel Ezell, Fortune's Merry Wheel, 1960.

- ^ Bellhouse, D.R., “The Genoese Lottery”, Statistical Science, vol. 6, No. 2. (May, 1991), pp. 141 -148

- ^ "Legalized Gambling; America's Bad Bet" by John Eidsmoe

(3). The Lottery Encyclopedia, 1986 by Ron Shelley (NY Public Library)

(4). A History of English Lotteries, by John Ashton, London: Leadenhall Press 1893

(5). Fortune's Merry Wheel, by John Samuel Ezell, Harvard University Press 1960.

(6) Lotteries and Sweepstakes, 1932 by Ewen L'Estrange

External links

- Wintrillions

- World Lottery Association

- North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries

- Multi-State Lottery Association

- FTC Consumer Alert on International Lotteries

- Euler's Analysis of the Genoese Lottery

- Lotto Millionaire Numbers A site dedicated to picking numbers for Lottery Games based on the real odds of winning.

- Lotto-LogixA directory of lottery resources and information sources.