Qin Shi Huang

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2007) |

| Qin Shi Huang | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reign | July 247 BCE–221 BCE |

| Reign | 221 BCE–Sept. 10, 210 BCE |

The monarch known now as Qin Shi Huang (Chinese: 秦始皇; pinyin: Qín Shǐ Huáng; Wade–Giles: Ch'in Shih-huang) (259 BCE – September 10, 210 BCE),[1] personal name Yíng Zhèng, was king of the Chinese State of Qin from 247 BCE to 221 BCE (officially still under the Zhou Dynasty), and then the first emperor of a unified China from 221 BCE to 210 BCE, ruling under the name the First Emperor (Chinese: 始皇帝; pinyin: Shǐ Huáng Dì; Wade–Giles: Shih Huang-Ti). As the ruler of the Great Qin, he was known for the introduction of Legalism and also for unifying China.

Qin Shi Huang remains a controversial figure in Chinese history. Having unified China, he and his chief adviser Li Si passed a series of major reforms aimed at cementing unification, and they undertook some gigantic projects, most notably the precursor version of the current Great Wall of China, a city-sized mausoleum guarded by a life-sized Terracotta Army, and a massive national road system, at the expense of numerous human lives. To ensure stability, he outlawed Confucianism and buried many of its scholars alive, banning and burning all books other than those officially decreed.

For all the tyranny of his autocratic rule, Qin Shi Huang is still regarded by many today as a pivotal figure in Chinese history whose unification of China has endured for more than two millennia.

Naming conventions

Qin Shi Huang was born in the Kingdom of Zhao, therefore he received the last name Zhao, which is a branch of "Ying". He was born in the Chinese month zhēng (正), the first month of the year in the Chinese calendar then in use, like January is now, and so he received the given name Zheng (政), both characters being used interchangeably in ancient China. In Chinese antiquity, people joined family names and given names together as is customary for all Chinese names today. Therefore, it is anachronistic to refer to Qin Shi Huang as "Zhao Zheng" or "Ying Zheng". The given name was never used except by close relatives; it is incorrect to call Qin Shi Huang "Prince Zheng", or alternatively by the common dynastic term "King Zheng of Qin". As a king, he was referred to as "King of Qin" only. Had he received a posthumous name after his death like his father, he would have been known by historians as "King NN. (posthumous name) of Qin".

After conquering the last independent Chinese state in 221 BCE, Qin Shi Huang was the king of a state of Qin ruling over the whole of China, an unprecedented accomplishment. Wishing to show that he was no longer a simple king like the kings of old during the Warring States Period, he created a new title, huangdi (皇帝), combining the word huang (皇) from the legendary Three Huang (Three August Ones) who ruled at the dawn of Chinese history, and the word di (帝) from the legendary Five Di (Five Sovereigns) who ruled immediately after the Three Huang. These Three Huang and Five Di were considered perfect rulers, of immense power and very long lives. The word huang also meant "big", "great". The word di also referred to the Supreme God in Heaven, creator of the world. Thus, by joining these two words for the first time, Qin Shi Huang created a title on a par with his feat of uniting the seemingly endless Chinese realm, in fact uniting the world. Ancient Chinese, like ancient Romans, believed their empire encompassed the whole world, a concept referred to as all under heaven.

This word huangdi is rendered in English as "emperor", a word which also has a long history dating back to ancient Rome (although "emperor" derived from imperator, which denoted the head of the military), and which English-speakers commonly deem to be superior to the word "king". Qin Shi Huang adopted the name First Emperor (Shi Huangdi, literally "commencing emperor"). He abolished posthumous names, by which former kings were known after their death, judging them inappropriate and contrary to filial piety, and decided that future generations would refer to him as the First Emperor (Shi Huangdi). His successor would be referred to as the Second Emperor (Er Shi Huangdi, literally "second generation emperor"), the successor of his successor as the Third Emperor (San Shi Huangdi, literally "third generation emperor"), and so on, for ten thousand generations, as the Imperial house was supposed to rule China for that long. ("Ten thousand" is equivalent to "forever" in Chinese, and also signifies "good fortune".)

Qin Shi Huang had now become the First Emperor of the State of Qin. The official name of the newly united China was still "State of Qin", as Qin had absorbed all the other states. The contemporaries called the emperor "First Emperor", dropping the phrase "of the State of Qin", which was obvious without saying. However, soon after the emperor's death, his regime collapsed, and China was beset by a civil war. Eventually, in 202 BCE the Han Dynasty managed to reunify the whole of China, which now became officially known as the State of Han (漢國), or Empire of Han. Qin Shi Huang could no longer be called "First Emperor", as this would imply that he was the "First Emperor of the Empire of Han". The custom thus arose of preceding his name with Qin (秦), which no longer referred to the State of Qin, but to the Qin Dynasty, a dynasty replaced by the Han Dynasty. The word huangdi (emperor) in his name was also shortened to huang, so that he became known as Qin Shi Huang. It seems likely that huangdi was shortened to obtain a three-character name, because it is rare for Chinese people to have a name composed of four or more characters.

This name Qin Shi Huang (i.e., "First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty") is the name that appears in the Records of the Grand Historian written by Sima Qian, and is the name most favored today inside China when referring to the First Emperor. Westerners sometimes write "Qin Shi Huangdi", which is improper given Chinese naming conventions; it is more conventional to write "Qin Shi Huang" or "First Emperor of Qin".

Youth and King of Qin: the conqueror

At the time of the young Zheng's birth, China was divided into warring feudal states. This period of Chinese history is referred to as the Warring States Period. The competition was extremely fierce and by 260 BC there were only a handful of states left (the others having been conquered and annexed), including Zheng's state, Qin, which was the most powerful. It was governed by a Legalist government and focused earnestly on military matters. Legalism taught that laws were obeyed out of fear not respect.

Zheng was born in Handan, the capital of the enemy State of Zhao, so he had the name Zhao Zheng. He was the son of Zichu (子楚), a prince of the royal house of Qin who served as a hostage in the State of Zhao under an agreement between the states of Qin and Zhao. Zichu later returned to Qin after many adventures and with the help of a rich merchant called Lü Buwei, and he managed to ascend the throne of Qin, Lü Buwei becoming chancellor (prime minister) of Qin. Zichu is known posthumously as King Zhuangxiang of Qin. According to a widespread story, Zheng was not the actual son of Zichu, but the son of the powerful chancellor Lü Buwei. This tale arose because Zheng's mother had originally been a concubine of Lü Buwei before he gave her to his good friend Zichu shortly before Zheng's birth. However, the story is dubious since the Confucians would have found it much easier to denounce a ruler whose birth was illegitimate.

Zheng ascended the throne in 245 BC at the age of 13, and was king under a regent until 238 BC when, at the age of 21 and a half, he staged a palace coup and assumed full power. Contrary to the accepted rules of war of the time, he ordered the execution of prisoners of war. He continued the tradition of tenaciously attacking and defeating the feudal states (dodging a celebrated assassination attempt by Jing Ke while doing so) and finally took control of the whole of China in 221 BC by defeating the last independent Chinese state, the State of Qi.

Then in that same year, at the age of 38, the king of Qin proclaimed himself First Emperor of the unified states of China, making him the most powerful man in China (see chapter above).

First Emperor: the unifier

Shǐ Huángdì

"First Emperor"

(small seal script

from 220 BCE)

In an attempt to avoid a recurrence of the political chaos of the Warring States Period, Qin Shi Huang and his prime minister Li Si completely abolished feudalism. They instead divided the empire into thirty-six commanderies. Power in the commanderies was in the hands of governors dismissed at will by the central government. Civilian and military powers were also separated to avoid too much power falling in the hands of a single civil servant. Thus, each commandery was run by a civilian governor (守 shōu) assisted by a military governor (尉 wèi). The civilian governor was superior to the military governor, a constant in Chinese history. The civilian governor was also reassigned to a different commandery every few years to prevent him from building up a base of power. An inspector (監 jiàn) was also in post in each commandery, in charge of informing the central government about the local implementation of central policies, reporting on the governors' exercise of power, and possibly resolving conflicts between the two governors.

This administrative system was only an extension to the whole empire of the system already in place in the State of Qin before the Chinese unification. In the State of Qin, feudalism had been abolished in the 4th century BCE, and the realm had been divided into commanderies, with centrally appointed governors.

Qin Shi Huang commanded all the members of the former royal houses of the conquered states to move to Xianyang, the capital of Qin, in modern day Shaanxi province, so they could be kept under tight surveillance for rebellious activities. Qin Shi Huang also ordered most previously existing books burned, excepting some medical and agricultural texts held in the palace archives.

Qin Shi Huang and Li Si unified China economically by standardizing the Chinese units of measurements such as weights and measures, the currency, the length of the axles of carts (so every cart could run smoothly in the ruts of the new roads), the legal system, and so on. The emperor also developed an extensive network of roads and canals connecting the provinces to improve trade between them and to accelerate military marches to revolting provinces.

Perhaps most importantly, the Chinese script was unified. Under Li Si, the seal script of the state of Qin, which had already evolved organically during the Eastern Zhou out of the Zhou dynasty script, was standardized through removal of variant forms within the Qin script itself. This newly standardized script was then made official throughout all the conquered regions, thus doing away with all the regional scripts and becoming the official script for all of China. Contrary to popular belief, Li Si did not invent the script, nor was it completely new at the time. Edicts written in the new script were carved on the walls of sacred mountains around China, such as the famous carved edicts of Mount Taishan, to let Heaven know of the unification of Earth under an emperor, and also to propagate the new script among people. However, the script was difficult to write, and an informal Qin script, variously termed vulgar or common writing, remained in use which was already evolving into an early form of clerical script.

Shi Huang made the color black the official court color. Among the five primary elements, the color for water is black. He often claimed that to Qin belongs the virtue of water. This might be due to his "taming of the Yellow River", a process of building numerous massive dams and tributaries to the Yellow River. Such an enormous undertaking certainly would not have been possible without a unified China.

Qin Shi Huang continued military expansion during his reign, annexing regions to the south (what is now Guangdong province was penetrated by Chinese armies for the first time) and fighting nomadic tribes to the north and northwest. These tribes (the Xiongnu) were subdued, but the campaign was essentially inconclusive, and to prevent the Xiongnu from encroaching on the northern frontier any longer, the emperor ordered the construction of an immense defensive wall, linking several walls already existing since the time of the Warring States.

This wall, for whose construction hundreds of thousands of men were mobilized, and an unknown number died, is a precursor of the current Great Wall of China. It was built much further north than the current Great Wall, which was built during the Ming Dynasty, when China had at least twice as many inhabitants as in the days of the First Emperor, and when more than a century was devoted to building the wall (as opposed to a mere ten years during the rule of the First Emperor). Very little survives today of the great wall built by the First Emperor.

By his order, 12 Jin Ren, 12 bronze colossi were made from the collected weapons after his unification of China.

Death and aftermath

Later in his life, Qin Shi Huang feared death and desperately sought the fabled elixir of life, visiting Zhifu Island several times to this end. He even sent a Zhifu islander Xu Fu with ships carrying hundreds of young men and women in search of Mount Penglai, where the Eight Immortals lived. These people never returned, as they knew that if they returned without the promised elixir, they would surely be executed. Legends claim that they settled down in one of the Japanese islands, a view that many Chinese and Japanese people are familiar with today.

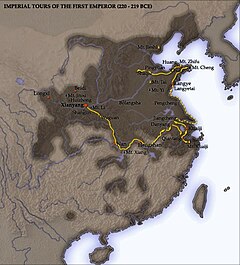

The emperor often took tours to major cities in his empire to inspect the efficiency of the bureaucracy and to symbolize the presence of Qin's prestige. Nevertheless, these trips provided opportunities for assassins, the most famous of whom was Zhang Liang. After his assassination had been attempted too often for comfort, he grew paranoid of remaining in one place too long and would hire servants to bear him to different buildings in his palace complex to sleep in each night. He also hired several "doubles" to make it less clear which figure was the emperor.

The emperor died while on one of his tours to Eastern China, on September 10, 210 BCE (Julian Calendar) at the palace in Shaqiu prefecture, about two months away by road from the capital Xianyang. Reportedly, he died of swallowing mercury pills, made by his court scientists and doctors, which contained too much of the liquid metal. Ironically, these pills were meant to make Qin Shi Huang immortal. The "theory," devised by alchemists, was that if mercury could even absorb gold, then if eaten, it would give that person its own powers, making him immortal. Mercury compounds were mixed with some food so as to make it edible.

Prime Minister Li Si, who accompanied him, was extremely worried that the news of his death could trigger a general uprising in the empire, given the brutal policies of the government, and the resentment of the population forced to work on Herculean projects such as the Great Wall in the north of China or the mausoleum of the emperor.

It would take two months for the government to reach the capital, and it would not be possible to stop the uprising. Li Si decided to hide the death of the emperor, and return to Xianyang. Most of the imperial entourage accompanying the emperor was left uninformed of the emperor's death, and each day Li Si entered the wagon where the emperor was supposed to be traveling, pretending to discuss affairs of state.

The secretive nature of the emperor while alive allowed this stratagem to work, and it did not raise doubts among courtiers. Li Si also ordered that two carts containing fish be carried immediately before and after the wagon of the emperor. The idea behind this was to prevent people from noticing the foul smell emanating from the wagon of the emperor, where his body was starting to decompose severely.

Eventually, after about two months, Li Si and the imperial court were back in Xianyang, where the news of the death of the emperor was announced.

Qin Shi Huang did not like to talk about death and he never really wrote a will. After his death, Li Si and the chief eunuch Zhao Gao persuaded his eighteenth son Huhai to forge the Emperor's will. Li Si was afraid that if Prince Fusu ascended the throne, it would endanger his position since Fusu was once exiled by the late emperor because of Li's thoughts.

They forced his first son Fusu to commit suicide, stripped the command of troops from Meng Tian, a loyal supporter of Fusu, and killed his family. Huhai became the Second Emperor (Er Shi Huangdi), known by historians as Qin Er Shi.

Qin Er Shi was not nearly as capable as his father. Revolts against him quickly erupted. His reign was a time of extreme civil unrest, and everything the First Emperor had worked for crumbled away, within a short period. The imperial palace and state archives were burned: this has been disastrous for later historians, because after the burning of the books by his father, almost the only written records left were those in the palace archives.

Within four years of Qin Shi Huang's death, his son was killed by Zhao Gao when the rebellious army approached the capital, and soon the Qin Dynasty crumbled to civil strife. Zhao Gao then appointed Fusu's son, Ziying, to be the next emperor. Ziying tricked Zhao Gao by refusing to attend his coronation, then stabbed the eunuch to death. But Liu Bang's army had approached the capital, and Ziying was forced to take an immediate decision of abdication, in order to avoid another ruthless rebel general, Xiang Yu, who was notorious for his brutality. Liu Bang then founded the Han dynasty.

Han Dynasty, rejected legalism (in favor of Confucianism) and moderated the laws, but kept Qin Shi Huang's basic political and economic reforms intact. In this way his work was carried on through the centuries and became a lasting feature of Chinese society.

Mausoleum and Terracotta Army

- Terracota army

Qin Shi Huang was buried in his mausoleum, with the famous Terracotta Army, near modern day Xi'an (Shaanxi province).

For 2000 years, a secret army of clay soldiers protected the hidden tomb of China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang. Until 1974 none knew of its existence; now Chinese archaeologists are gradually unfolding the mystery.

The site measures some three miles across[citation needed]. The Chinese historian Sima Qian, writing a century after the First Emperor's death, wrote that it took 700,000 men to construct it. The British historian John Man points out that this figure is larger than any city of the world at that time and calculates that the foundations could have been built by 16,000 men in two years.[2] Sima Qin's description of the tomb includes replicas of palaces and scenic towers, 'rare utensils and wonderful objects', 100 rivers made with mercury, representations of 'the heavenly bodies', and crossbows rigged to shoot anyone who tried to break in.[3]

Sima Qian never mentioned, however, the terracotta army - which was discovered by a team of well diggers. It is the detail of the terracotta armies that makes it so valuable. The soldiers were created with a series of mix-and-match clay molds and then further individualized by the artists' hand.

All the standing warriors were attached to clay plinths that rested on the tiled floor, which still resembles a modern pavement. Chinese archaeologists have been meticulous and patient in their work.

- Qin Shi Huang Tomb

The main tomb (located at 34°22′52.75″N 109°15′13.06″E / 34.3813194°N 109.2536278°E) containing the emperor has yet to be opened and there is evidence suggesting that it remains relatively intact.[4]

Historiography of Qin Shi Huang

In traditional Chinese historiography, the First Emperor of the Chinese unified states was almost always portrayed as a brutal tyrant, superstitious (a result of his interest in immortality and assassination paranoia), and sometimes even as a mediocre ruler.

Ideological prejudices against the Legalist State of Qin were established as early as 266 BCE, when Confucian philosopher Xun Zi disparaged it. Later Confucian historians condemned the emperor who had burned the classics and buried Confucian scholars alive. They eventually compiled a list of the Ten Crimes of Qin to highlight his tyrannical actions.

The famous Han poet and statesman Jia Yi concluded his essay The Faults of Qin (过秦论), with what was to become the standard Confucian judgment of the reasons for Qin's collapse. Jia Yi's essay, admired as a masterpiece of rhetoric and reasoning, was copied into two great Han histories and has had a far-reaching influence on Chinese political thought as a classic illustration of Confucian theory.

He explained the ultimate weakness of Qin as a result of its ruler's ruthless pursuit of power, harsh laws and unbearable burdens placed on the population in projects such as the Great Wall - the precise factor which had made it so powerful; for as Confucius had taught, the strength of a government ultimately is based on the support of the people and virtuous conduct of the ruler.

Because of this systematic Confucian bias on the part of Han scholars, some of the stories recorded about Qin Shi Huang are doubtful and some may have been invented to emphasize his bad character. Some of the stories are plainly fictitious, designed to tarnish the First Emperor's image, e.g. the story of a stone fallen from the sky engraved with words denouncing the emperor and prophesying the collapse of his empire after his death.

This makes it difficult to know the truth about other stories. For instance, the accusation that he had 460 scholars executed by having them buried with only their heads above ground and then decapitated seems unlikely to be completely true, but we have no way to know for certain.

Only in modern times were historians able to penetrate beyond the limitations of traditional Chinese historiography. The political rejection of the Confucian tradition as an impediment to China's entry into the modern world opened the way for changing perspectives to emerge.

In the three decades between the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the outbreak of the Second World War, with the deepening dissatisfaction with China's weakness and disunity, there emerged a new appreciation of the man who had unified China.

In the time when he was writing, when Chinese territory was encroached upon by foreign nations, leading Kuomintang historian Xiao Yishan emphasized the role of Qin Shi Huang in repulsing the northern barbarians, particularly in the construction of the Great Wall.

Another historian, Ma Feibai (马非百), published in 1941 a full-length revisionist biography of the First Emperor entitled Qin Shi Huangdi Zhuan (《秦始皇帝传》), calling him "one of the great heroes of Chinese history".

Ma compared him with the contemporary leader Chiang Kai-shek and saw many parallels in the careers and policies of the two men, both of whom he admired. Chiang's Northern Expedition of the late 1920s, which directly preceded the new Nationalist government at Nanjing was compared to the unification brought about by Qin Shi Huang.

With the coming of the Communist Revolution in 1949, new interpretations again surfaced. The establishment of the new, revolutionary regime meant another re-evaluation of the First Emperor, this time following Marxist theory.

The new interpretation given of Qin Shi Huang was generally a combination of traditional and modern views, but essentially critical. This is exemplified in the Complete History of China, which was compiled in September 1955 as an official survey of Chinese history.

The work described the First Emperor's major steps toward unification and standardisation as corresponding to the interests of the ruling group and the merchant class, not the nation or the people, and the subsequent fall of his dynasty a manifestation of the class struggle.

The perennial debate about the fall of the Qin Dynasty was also explained in Marxist terms, the peasant rebellions being a revolt against oppression — a revolt which undermined the dynasty, but which was bound to fail because of a compromise with "landlord class elements".

Since 1972, however, a radically different official view of Qin Shi Huang has been given prominence throughout China. The re-evaluation movement was launched by Hong Shidi's biography Qin Shi Huang. The work was published by the state press to be a mass popular history, and it sold 1.85 million copies within two years.

In the new era, Qin Shi Huang was seen as a farsighted ruler who destroyed the forces of division and established the first unified, centralized state in Chinese history by rejecting the past. Personal attributes, such as his quest for immortality, so emphasized in traditional historiography, were scarcely mentioned.

The new evaluations described how, in his time (an era of great political and social change), he had no compunctions in using violent methods to crush counter-revolutionaries, such as the "industrial and commercial slave owner" chancellor Lü Buwei. Unfortunately, he was not as thorough as he should have been and after his death, hidden subversives, under the leadership of the chief eunuch Zhao Gao, seized power and used it to restore the old feudal order.

To round out this re-evaluation, a new interpretation of the precipitous collapse of the Qin Dynasty was put forward in an article entitled "On the Class Struggle During the Period Between Qin and Han" by Luo Siding, in a 1974 issue of Red Flag, to replace the old explanation. The new theory claimed that the cause of the fall of Qin lay in the lack of thoroughness of Qin Shi Huang's "dictatorship over the reactionaries, even to the extent of permitting them to worm their way into organs of political authority and usurp important posts."

Qin Shi Huang was ranked #17 in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

Mao Zedong, chairman of the People's Republic of China, was reviled for his persecution of intellectuals. Being compared to the First Emperor, Mao responded: "He buried 460 scholars alive; we have buried forty-six thousand scholars alive... You [intellectuals] revile us for being Qin Shi Huangs. You are wrong. We have surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold."[5]

Qin Shi Huang in fiction

- During the Korean War, the play Song of the Yi River was produced. The play was based on the attempted assassination of Qin Shi Huang (called "Ying Zheng") by Jing Ke of Wei, at the request of the Prince of Yan, in 227 BCE. In the play Ying Zheng was portrayed as a cruel tyrant and an aggressor and invader of other states. Jing Ke, in contrast, was a chivalrous warrior who said that "tens of thousands of injured people are all my comrades." A huge newspaper ad for this play proclaimed: "Invasion will definitely end in defeat; peace must be won at a price." The play portrayed an underdog fighting against a cruel, powerful foreign invader with help from a sympathetic foreign volunteer.

- Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986), the Argentine writer, wrote an acclaimed essay on Qin Shi Huang, 'The Wall and the Books' (La muralla y los libros), included in the 1952 collection Other Inquisitions (Otras Inquisiciones). It muses on the opposition between large-scale construction (the Wall) and destruction (book-burning) that defined his reign, in order to make a point about 'the aesthetic experience'.

- The book Lord of the East, published in 1956, is a historical romance about the favourite daughter of Qin Shihuang, who runs away with her lover. The story uses Qin Shihuang to create the barrier for the young couple.

- The 1984 book Bridge of Birds (by Barry Hughart) portrays the emperor as a power-hungry megalomaniac who achieved immortality by having his heart removed by an "Old Man of the mountain."

- The Chinese Emperor, by Jean Levi, appeared in 1984. This work of historical fiction moves from discussions of politics and law in the Qin state to fantasy, in which the First Emperor's terracotta soldiers were actually robots created to replace fallible humans.

- In the Area 51 book series, Qin Shi Huang is revealed to be an alien exile stranded on Earth during an interstellar civil war. The Great Wall is actually designed to display the symbol for 'help' in his language, and he orders it built in the hope that a passing spaceship would notice it and rescue him.

- In Hydra's Ring, the 39th novel in the Outlanders series, Shi Huang Di is revealed to be still alive in the early 23rd century through extraterrestrial nano-technology that has bestowed a form of immortality.

- In the Magic Tree House book series, one book is titled "Day of the Dragon King." The Dragon King is Qin Shi Huangdi.

Films and television

- The 1963 Japanese movie Shin No Shikoutei portrays Qin Shihuang as a battle-hardened emperor with his roots in the military. Despite his rank, he is shown lounging around a campfire with common men. A female character, Lady Chu, serves as a foil who questions whether the emperor's cause is just. He converts her from an enemy to a loyal concubine.

- In the 1986 film Big Trouble in Little China, the First Emperor is said to have been responsible for the sorcerer Lo Pan's curse.

- Hong Kong Asia Television Limited (ATV) Channel made a TV drama called "The Rise of the Great Wall - Emperor Qin Shi Huang" (秦始皇) during the 1980s. It was one of ATV's most expensive projects, with 63 episodes chronicling Qin Shi Huang's life from his birth to his death. The title song summed up most of the storyline: "The land shall be under my foot; nobody shall be equal to me."

- The 1996 movie The Emperor's Shadow uses legends about Qin Shi Huang to make a political statement on Chinese Communism. The film focuses on his relationship with the rebellious musician Gao Jianli, known historically as a friend of the would-be assassin Jing Ke. Gao plays a song for the assassin before he sets out to kill the emperor.

- The 1999 movie The Emperor and the Assassin focuses on the identity of the emperor's father, his supposed heartless treatment of his officials, and a betrayal by his childhood lover, paving the way for Jing Ke's assassination attempt. The director of the film, Chen Kaige, sought to question whether the emperor's motives were meritorious. A major theme in this movie is the conflict between the Emperor’s dedication to his vows and to his lover, Lady Zhao.

- In the animated series Histeria, Pepper Mills wanted Shi Huang Di's autograph, thinking he was Scooby Doo.

- The 2001 Hong Kong TVB serial drama A Step into the Past, based on a book with the same title, stars Raymond Lam Fung as Zhao Pan, a man from the Kingdom of Zhao who takes over the identity of the emperor (called "Ying Zheng") and rises to power. He is unwittingly helped by Hong Siu Lung, a time traveller from the 21st century.

- The 2002 movie Hero, starring Jet Li, tells the story of assassination attempts on Qin Shi Huang (played by renowned Chinese actor Chen Daoming) by legendary warriors. It portrays him as a powerful ruler willing to take any steps to bring unification to his people.

- In 2005 The Discovery Channel ran a drama-documentary special on Qin Shi Huang called First Emperor: The Man Who Made China, featuring James Pax as the emperor. It was shown on the UK Channel 4 in 2006.

- In The Myth (2005), Jackie Chan plays both a modern-day archaeologist and a general under Qin Shi Huang. Kim Hee-sun starred alongside Jackie Chan as a Korean Princess who was forced to marry Qin Shi Huang.

- Bob Bainborough portrayed Qin Shi Huang in an episode of History Bites.

- In the animated Martin Mystery series, the hero finds that the Terracotta Army is actually kept to keep the First Emperor inside his tomb and not help him in the spiritual world.

- In My Date With A Vampire series 2, a flashback shows that Qin Shi Huang was the Emperor who was deceived that the way to having Immortality was found, and was turned into a vampire.

- In the 2008 film The Mummy: The Tomb of the Dragon Emperor, Qin Shi Huang is the film's villain and is played by Jet Li.

Music

- Emperor Qin is the protagonist in the opera The First Emperor by Tan Dun and has been sung by Plácido Domingo on its world premiere.

Video games

- The 1995 computer game Qin: Tomb of the Middle Kingdom depicts a fictional archaeological mission to explore the First Emperor's burial site. The emperor is featured in several voiceovers in Mandarin Chinese.

- The video game Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb portrays Indiana Jones entering the tomb of Qin Shi Huang to recover "The Heart of the Dragon".

- In the 2002 computer game Prince Of Qin, the user plays as Qin Shi Huang's first son Fu Su, who was forced to commit suicide in history. But in this game, Fu Su does not die, he will fight for his birth right to inherit the throne and seek for the truth of Qin Shi Huang's death.

- In the 2005 computer game Civilization IV, Qin Shi Huang is one of the two playable leaders of China. The other is Mao Zedong.

- In the computer game Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom, the Qin Dynasty campaign has the player as the head architect of Qin Shi Huang, in charge of seeing the construction of the capitol, the great wall, as well as his tomb and the terracotta army, although the game takes liberties with the timeframes in which these events actually take place.

- The Playstation title Fear Effect 2: Retro Helix deals heavily with the myths of the emperor's tomb, and The Eight Immortals.

References

- ^ "Emperor Qin Shi Huang -- First Emperor of China". TravelChinaGuide.com. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ Mann, John The Terracotta Army, Bantam Press 2007 p125

- ^ Mann, John The Terracotta Army, Bantam Press 2007 p170

- ^ Jane Portal and Qingbo Duan, The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Arm, British Museum Press, 2007, p. 207

- ^ Mao Zedong sixiang wan sui! (1969), p. 195. Referenced in Governing China (2nd ed.) by Kenneth Lieberthal (2004).

Further reading

- Wood, Frances (2007). The First Emperor of China. Profile. ISBN 1846680328.