Glucose

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane

-2,3,4,5-tetrol OR (2R,3R,4S,5R,6R)-6 -(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro -2H-pyran-2,3,4,5-tetraol | |

| Other names

Dextrose

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| Abbreviations | Glc |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.156 g mol−1 |

| Density | 1.54 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | α-D-glucose: 146°C β-D-glucose: 150°C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Glucose (Glc), a monosaccharide (or simple sugar) also known as grape sugar, blood sugar, or corn sugar, is a very important carbohydrate in biology. The living cell uses it as a source of energy and metabolic intermediate. Glucose is one of the main products of photosynthesis and starts cellular respiration in both prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) and eukaryotes (animals, plants, fungi, and protists).

The name glucose comes from the Greek word glykys (γλυκύς), meaning "sweet", plus the suffix "-ose" which denotes a sugar.

Two stereoisomers of the aldohexose sugars are known as glucose, only one of which (D-glucose) is biologically active. This form (D-glucose) is often referred to as dextrose monohydrate, or, especially in the food industry, simply dextrose (from dextrorotatory glucose[1]). This article deals with the D-form of glucose. The mirror-image of the molecule, L-glucose, cannot be metabolized by cells in the biochemical process known as glycolysis.

Structure

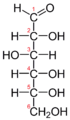

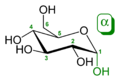

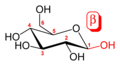

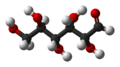

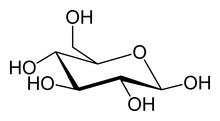

Glucose (C6H12O6) contains six carbon atoms, one of which is part of an aldehyde group, and is therefore referred to as an aldohexose. In solution, the glucose molecule can exist in an open-chain (acyclic) form and a ring (cyclic) form (in equilibrium). The cyclic form is the result of a covalent bond between the aldehyde C atom and the C-5 hydroxyl group to form a six-membered cyclic hemiacetal. At pH 7 the cyclic form is predominant. In the solid phase, glucose assumes the cyclic form. Because the ring contains five carbon atoms and one oxygen atom, which resembles the structure of pyran, the cyclic form of glucose is also referred to as glucopyranose. In this ring, each carbon is linked to a hydroxyl side group with the exception of the fifth atom, which links to a sixth carbon atom outside the ring, forming a CH2OH group. Glucose is commonly available in the form of a white substance or as a solid crystal. It can also be dissolved in water as an aqueous solution.

Isomers

Aldohexose sugars have 4 chiral centers giving 24 = 16 stereoisomers. These are split into two groups, L and D, with 8 sugars in each. Glucose is one of these sugars, and L-glucose and D-glucose are two of the stereoisomers. Only 7 of these are found in living organisms, of which D-glucose (Glu), D-galactose (Gal), and D-mannose (Man) are the most important. These eight isomers (including glucose itself) are related as diastereoisomers and belong to the D series.

An additional asymmetric center at C-1 (called the anomeric carbon atom) is created when glucose cyclizes and two ring structures called anomers are formed as α-glucose and β-glucose. These anomers differ structurally by the relative positioning of the hydroxyl group linked to C-1, and the group at C-6 which is termed the reference carbon. When D-glucose is drawn as a Haworth projection or in the standard chain conformation, the designation α means that the hydroxyl group attached to C-1 is positioned trans to the -CH2OH group at C-5, while β means it is cis. An inaccurate but superficially attractive alternative method of distinguishing α from β is by observing whether the C-1 hydroxyl is below or above the plane of the ring; this may fail if the glucose ring is drawn upside down or in an alternative chair conformation. The α and β forms interconvert over a timescale of hours in aqueous solution, to a final stable ratio of α:β 36:64, in a process called mutarotation.[2] The ratio would be α:β 11:89 if it weren't for the influence of the anomeric effect.[3]

-

The Fischer projection of the chain form of D-glucose -

The chain form of D-glucose -

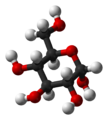

α-D-

glucopyranose -

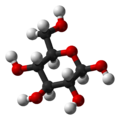

β-D-

glucopyranose -

Chain form: ball-and-stick model -

Chain form: space-filling model -

α-D-

glucopyranose -

β-D-

glucopyranose

Rotamers

Within the cyclic form of glucose, rotation may occur around the O6-C6-C5-O5 torsion angle, termed the ω-angle, to form three rotamer conformations as shown in the diagram below. Referring to the orientations of the ω-angle and the O6-C6-C5-C4 angle the three stable staggered rotamer conformations are termed gauche-gauche (gg), gauche-trans (gt) and trans-gauche (tg). For methyl α-D-glucopyranose at equilibrium the ratio of molecules in each rotamer conformation is reported as 57:38:5 gg:gt:tg.[4] This tendency for the ω-angle to prefer to adopt a gauche conformation is attributed to the gauche effect.

Properties and energy content

The Gibbs free energy of formation of solid glucose is -909 kJ/mol and the enthalpy of formation is -1271.1 kJ/mol. The heat of combustion (with liquid water in the product) is about 2803 kJ/mol, or 3.72 kcal per gram. The ΔG (change of Gibbs free energy) for this combustion is about -2880 kJ/mol.

Upon heating, glucose, like any carbohydrate, will undergo caramelization, followed by pyrolysis (carbonization) yielding steam and a char consisting mostly of carbon. This reaction is exothermic, releasing about 0.237 kcal per gram.

Production

Natural

- Glucose is one of the products of photosynthesis in plants and some prokaryotes.

- In animals and fungi, glucose is the result of the breakdown of glycogen, a process known as glycogenolysis. In plants the breakdown substrate is starch.

- In animals, glucose is synthesized in the liver and kidneys from non-carbohydrate intermediates, such as pyruvate and glycerol, by a process known as gluconeogenesis.

Commercial

Glucose is produced commercially via the enzymatic hydrolysis of starch. Many crops can be used as the source of starch. Maize, rice, wheat, potato, cassava, arrowroot, and sago are all used in various parts of the world. In the United States, cornstarch (from maize) is used almost exclusively.

-

Glucose

-

Glucose tablets

Function

Scientists can speculate on the reasons why glucose, and not another monosaccharide such as fructose (Fru), is so widely used in organisms. One reason might be that glucose has a lower tendency, as compared to other hexose sugars, to non-specifically react with the amino groups of proteins. This reaction (glycation) reduces or destroys the function of many enzymes. The low rate of glycation is due to glucose's preference for the less reactive cyclic isomer. Nevertheless, many of the long-term complications of diabetes (e.g., blindness, kidney failure, and peripheral neuropathy) are probably due to the glycation of proteins or lipids. In contrast, enzyme-regulated addition of glucose to proteins by glycosylation is often essential to their function.[5]

As an energy source

Glucose is an ubiquitous fuel in biology. It is used as an energy source in most organisms, from bacteria to humans. Use of glucose may be by either aerobic or anaerobic respiration (fermentation). Carbohydrates are the human body's key source of energy, through aerobic respiration, providing approximately 3.75 kilocalories (16 kilojoules) of food energy per gram.[6] Breakdown of carbohydrates (e.g. starch) yields mono- and disaccharides, most of which is glucose. Through glycolysis and later in the reactions of the Citric acid cycle (TCAC), glucose is oxidized to eventually form CO2 and water, yielding energy sources, mostly in the form of ATP. The insulin reaction, and other mechanisms, regulate the concentration of glucose in the blood. A high fasting blood sugar level is an indication of prediabetic and diabetic conditions.

Glucose is a primary source of energy for the brain, and hence its availability influences psychological processes. When glucose is low, psychological processes requiring mental effort (e.g., self-control, effortful decision-making) are impaired.[7][8][9][10]

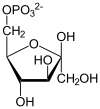

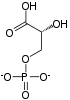

Glucose in glycolysis

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Compound C00031 at KEGG Pathway Database. Enzyme 2.7.1.1 at KEGG Pathway Database. Compound C00668 at KEGG Pathway Database. Reaction R01786 at KEGG Pathway Database. | ||||||||||||||||||||

Use of glucose as an energy source in cells is via aerobic or anaerobic respiration. Both of these start with the early steps of the glycolysis metabolic pathway. The first step of this is the phosphorylation of glucose by hexokinase to prepare it for later breakdown to provide energy.

The major reason for the immediate phosphorylation of glucose by a hexokinase is to prevent diffusion out of the cell. The phosphorylation adds a charged phosphate group so the glucose 6-phosphate cannot easily cross the cell membrane. Irreversible first steps of a metabolic pathway are common for regulatory purposes.

As a precursor

Glucose is critical in the production of proteins and in lipid metabolism. Also, in plants and most animals, it is a precursor for vitamin C (ascorbic acid) production. It is modified for use in these processes by the glycolysis pathway.

Glucose is used as a precursor for the synthesis of several important substances. Starch, cellulose, and glycogen ("animal starch") are common glucose polymers (polysaccharides). Lactose, the predominant sugar in milk, is a glucose-galactose disaccharide. In sucrose, another important disaccharide, glucose is joined to fructose. These synthesis processes also rely on the phosphorylation of glucose through the first step of glycolysis.

In industry it is a precursor to vitamine C in the Reichstein process.

Sources and absorption

All major dietary carbohydrates contain glucose, either as their only building block, as in starch and glycogen, or together with another monosaccharide, as in sucrose and lactose. In the lumen of the duodenum and small intestine, the glucose oligo- and polysaccharides are broken down to monosaccharides by the pancreatic and intestinal glycosidases. Other polysaccarhides cannot be processed by the human intestine and require assistance by intestinal flora if they are to be broken down; the most notable exceptions are sucrose (fructose-glucose) and lactose (galactose-glucose). Glucose is then transported across the apical membrane of the enterocytes by SLC5A1, and later across their basal membrane by SLC2A2.[11] Some of the glucose goes directly toward fueling brain cells, intestinal cells, and red blood cells, while the rest makes its way to liver, adipose tissue, and muscle cells, where it is absorbed (under the influence of insulin) and stored as glycogen. Liver cell glycogen is (when insulin is low or absent) converted to glucose and returned to the blood, muscle cell glycogen is not returned to the blood as the necessary enzymes are lacking. In fat cells, glucose is used to power reactions which, among other things, synthesize some fat types. Glycogen is the body's 'glucose energy' storage mechanism as it is much more 'space efficient' and less reactive than glucose itself.

See also

- Blood glucose or Blood sugar

- HbA1c

- DMF (potential glucose-based biofuel)

- Glycation

- Glycosylation

- Photosynthesis

- Fructose

- Beriberi - vitamin deficiency affecting ability to convert carbohydrates into glucose

- Sugars in wine

References

- ^ dextrose - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

- ^ McMurry, John (1988). Organic Chemistry. Brooks/Cole. p. 866. ISBN 0534079687.

- ^ Juaristi, Eusebio (1995). The Anomeric Effect. CRC Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0849389410.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kirschner, K.N. Woods, R.J. (2001). "Solvent interactions determine carbohydrate conformation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98 (19): 10541–10545. doi:10.1073/pnas.191362798. PMID 11526221.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ citation needed

- ^ CHAPTER 3: CALCULATION OF THE ENERGY CONTENT OF FOODS - ENERGY CONVERSION FACTORS

- ^ Fairclough, S. H., & Houston, K. (2004). "A metabolic measure of mental effort". Biological Psychology. 66: 177–190. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001. PMID 15041139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gailliot, M.T., Baumeister, R.F., DeWall, C.N., Maner, J.K., Plant, E.A., Tice, D.M., Brewer, L.E., & Schmeichel, B.J. (2007). "Self-Control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 92: 325–336. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325. PMID 17279852.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gailliot, M.T., & Baumeister, R.F. (2007). "The physiology of willpower: Linking blood glucose to self-control". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 11: 303–327. doi:10.1177/1088868307303030. PMID 18453466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Masicampo, E.J., & Baumeister, R.F. (2008). "Toward a physiology of dual-process reasoning and judgment: Lemonade, willpower, and expensive rule-based analysis". Psychological Science. 19: 255–260. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02077.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferraris, Ronaldo P. (2001). "Dietary and developmental regulation of intestinal sugar transport". Biochemical Journal. 360 (360): 265–276. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600265. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

External links

- D-glucose EINECS number 200-075-1

- L-glucose EINECS number 213-068-3

- CID 5793 from PubChem (D-glucose)

- CID 206 from PubChem (L-glucose)

- Computational Chemistry Wiki

- What is Glucose