Neanderthal

| Neanderthal Temporal range: Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| File:Neanderthal child.jpg | |

| Reconstruction of a Neanderthal child from Gibraltar (Anthropological Institute, University of Zürich) | |

| |

| Mounted neanderthal skeleton, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. neanderthalensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo neanderthalensis King, 1864

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Palaeoanthropus neanderthalensis | |

The Neanderthal (Template:Pron-en, /ni(ː)ˈændərθɔːl/), or /neɪˈændərtɑːl/), or Neandertal, is an extinct member of the Homo genus that is known from Pleistocene specimens found in Europe and parts of western and central Asia. Neanderthals are either classified as a subspecies of humans (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) or as a separate species (Homo neanderthalensis).[1] The first proto-Neanderthal traits appeared in Europe as early as 600,000–350,000 years ago.[2] Proto-Neanderthal traits are occasionally grouped to another cladistic 'species', Homo heidelbergensis, or a migrant form, Homo rhodesiensis. By 130,000 years ago, complete Neanderthal characteristics had appeared. These characteristics then disappeared in Asia by 50,000 years ago and in Europe by 30,000 years ago.[3] The youngest Neanderthal finds include Hyaena Den (UK), considered older than 30,000 years ago, while the Vindija (Croatia) Neanderthals have been re-dated to between 32,000 and 33,000 years ago. No definite specimens younger than 30,000 years ago have been found; however, evidence of fire by Neanderthals at Gibraltar indicate that they may have survived there until 24,000 years ago. Modern human skeletal remains with 'Neanderthal traits' were found in Lagar Velho (Portugal), dated to 24,500 years ago and controversially interpreted as indications of extensively admixed populations.[4]

Neanderthal stone tools provide further evidence for their presence where skeletal remains have not been found. The last traces of Mousterian culture, a type of stone tools associated with Neanderthals, were found in Gorham's Cave on the remote south-facing coast of Gibraltar.[5] Other tool cultures sometimes associated with Neanderthal include Châtelperronian, Aurignacian, and Gravettian, with the latter extending to 22,000 years ago, the last indication of Neanderthal presence.

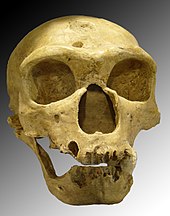

Neanderthal cranial capacity is often thought to have been as large or larger than modern humans, indicating that their brain size may have been the same or greater; however, a 1993 analysis of 118 hominid crania concluded that the cranial capacity of H.s. neandertal averaged 1,412 cc (86 cu in) while that of fossil modern H.s. sapiens averaged 1,487 cc (91 cu in).[6] On average, the height of Neanderthals was comparable to contemporaneous Homo sapiens. Neanderthal males stood about 165–168 cm (65–66 in) and were heavily built with robust bone structure. They were much stronger, having particularly strong arms and hands.[7] Females stood about 152–156 cm (60–61 in).[8] They were almost exclusively carnivorous[9] and apex predators.[10]

Etymology and classification

The Neandertal is a small valley of the river Düssel in the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located about 12 km (7.5 mi) east of Düsseldorf. Neanderthal is now spelled two ways: the old spelling of the German word Thal, meaning "valley or dale", was changed to Tal in 1901, but the former spelling is often retained in English and always in scientific names, while the modern spelling is always used in German in referring both to Neanderthals and the valley.

The Neandertal was named after theologian Joachim Neander, who lived nearby in Düsseldorf in the late 17th century. "Neander" is a classicized form of the common German surname Neumann. In turn, Neanderthals were named after "Neander Valley", where the first Neanderthal remains were found. The term Neanderthal Man was coined in 1863 by Anglo-Irish geologist William King.

The original German pronunciation (regardless of spelling) is with the sound /t/. In American English, the term is commonly anglicised to /θ/ (th as in thin), though scientists usually use /t/, and the latter, non-anglicised, pronunciation (followed by the German long a) is preferred in British English.

For some time, professionals debated whether Neanderthals should be classified as Homo neanderthalensis or as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, the latter placing Neanderthals as a subspecies of Homo sapiens. Genetic statistical calculation (2006 results) suggests at least 5% of the modern human gene pool can be attributed to ancient admixture, with the European contribution being from the Neanderthal.[11] Some morphological studies support that Homo neanderthalensis is a separate species and not a subspecies.[12] Some suggest inherited admixture. Others, for example University of Cambridge Professor Paul Mellars, say "no evidence has been found of cultural interaction"[13] and evidence from mitochondrial DNA studies have been interpreted as evidence Neanderthals were not a subspecies of H. sapiens.[14] A controversial study of Homo sapiens mtDNA from Australia (Mungo Man 40ky) suggested that its lineage was not part of the recent human genomic pool and mtDNA sequences for temporally comparative African specimens are not yet available.

Discovery

Neanderthal skulls were first discovered in Engis, Belgium (1829) by Philippe-Charles Schmerling and in Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar (1848), both prior to the "original" discovery in a limestone quarry of the Neander Valley in Erkrath near Düsseldorf in August, 1856, three years before Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published.[15]

The type specimen, dubbed Neanderthal 1, consisted of a skull cap, two femora, three bones from the right arm, two from the left arm, part of the left ilium, fragments of a scapula, and ribs. The workers who recovered this material originally thought it to be the remains of a bear. They gave the material to amateur naturalist Johann Carl Fuhlrott, who turned the fossils over to anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen. The discovery was jointly announced in 1857.

The original Neanderthal discovery is now considered the beginning of paleoanthropology. These and other discoveries led to the idea that these remains were from ancient Europeans who had played an important role in modern human origins. The bones of over 400 Neanderthals have been found since.

Specimens

- La Ferrassie 1: A fossilized skull discovered in La Ferrassie, France by R. Capitan in 1909. It is estimated to be 70,000 years old. Its characteristics include a large occipital bun, low-vaulted cranium and heavily worn teeth.

- Shanidar 1: Found in the Zagros Mountains in northern Iraq; a total of nine skeletons found believed to have lived in the Middle Paleolithic. One of the nine remains was missing part of its right arm; theorized to have been broken off or amputated. The find is also significant because it shows that stone tools were present among this tribe's culture. One was buried with flowers, showing that some type of burial ceremony may have occurred.

- La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1: Called the Old Man, a fossilized skull discovered in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France by A. and J. Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon in 1908. Characteristics include a low vaulted cranium and large browridge typical of Neanderthals. Estimated to be about 60,000 years old, the specimen was severely arthritic and had lost all his teeth, with evidence of healing. For him to have lived on would have required that someone process his food for him, one of the earliest examples of Neanderthal altruism (similar to Shanidar I.)

- Le Moustier: A fossilized skull, discovered in 1909, at the archaeological site in Peyzac-le-Moustier, Dordogne, France. The Mousterian tool culture is named after Le Moustier. The skull, estimated to be less than 45,000 years old, includes a large nasal cavity and a somewhat less developed brow ridge and occipital bun as might be expected in a juvenile.

- Neanderthal 1: Initial Neanderthal specimen found during an archaeological dig in August 1856. Discovered in a limestone quarry at the Feldhofer grotto in Neanderthal, Germany. The find consisted of a skull cap, two femora, the three right arm bones, two of the left arm bones, ilium, and fragments of a scapula and ribs.

Chronology

Bones with Neanderthal traits in chronological order.[clarification needed]

- > 350 Sima de los Huesos c. 500:350 hh/hn[16][17]

- 350–200 thousand years ago: Pontnewydd 225 thousand years ago.

- 200–135: Atapuerca,[18] Vértesszöllos, Ehringsdorf, Casal de'Pazzi, Biache, La Chaise, Montmaurin, Prince, Lazaret, Fontéchevade

- 135–45: Krapina, Saccopastore, Malarnaud, Altamura, Gánovce, Denisova, Okladnikov Altai, Pech de l'Azé, Tabun 120k ÷ 100±5,[19] Qafzeh9 100, Shanidar 1 to 9 80–60, La Ferrassie 1 70, Kebara 60, Régourdou, Mt. Circeo, Combe Grenal, Erd 50, La Chapelle-aux Saints 1 60, Amud, Teshik-Tash, .

- 45–35: Le Moustier 45, Feldhofer 42, La Quina, l'Horus, Hortus, Kulna, Šipka, Saint Césaire, Bacho Kiro, El Castillo, Bñnolas, Arcy-sur-Cure.[20]

- < 35: Chătelperron, Pestera cu Oase 35k, Figueria Brava, Mladeč 31k, Zafaraya 30,[20] Vogelherd 3?[21], Pestera Muierii 30k (n/s),[22] Vindija (Vi208, 32400][23]), Velika Pećina, Lagar Velho 24.5.

Anatomy

Neanderthals were generally only 12–14 cm (5–6 in) shorter than modern humans, contrary to a common view of them as "very short" or "just over 5 feet". Based on 45 long bones from (at most) 14 males and 7 females, Neanderthal males averaged 164–168 cm (65–66 in) and females 152–156 cm (60–61 in) tall. Compared to Europeans some 20,000 years ago, it is nearly identical, perhaps slightly taller. Considering the body build of Neanderthals, new body weight estimates show they are only slightly above the cm/weight or the body mass index of modern Americans or Canadians.[24]

Neanderthals had more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially of the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects, particularly in certain relatively isolated geographic regions. Evidence suggests they were much stronger than modern humans;[25] their relatively robust stature is thought to be an adaptation to the cold climate of Europe during the Pleistocene epoch.

A 2007 study suggested some Neanderthals may have had red hair and pale skin color.[26][27]

Distinguishing physical traits

The magnitude of autapomorphic traits in specimens differ in time. In the latest specimens, autapomorphy is fuzzy. The following is a list of physical traits which distinguish Neanderthals from modern humans; however, not all of them can be used to distinguish specific Neanderthal populations, from various geographic areas or periods of evolution, from other extinct humans. Also, many of these traits occasionally manifest in modern humans, particularly among certain ethnic groups traced to Neanderthal habitat ranges. Nothing is certain (from unearthed bones) about the shape of soft parts such as eyes, ears, and lips of Neanderthals.[28]

When comparing traits to worldwide average present day human traits in Neanderthal specimens, the following traits are distinguished. The magnitude on particular trait changes with 300,000 years timeline.

- Cranial

- Suprainiac fossa, a groove above the inion

- Occipital bun, a protuberance of the occipital bone which looks like a hair knot [29]

- Projecting mid-face

- Low, flat, elongated skull

- A flat basicranium[30][31][32]

- Supraorbital torus, a prominent, trabecular (spongy) brow ridge

- 1,200–1,900 cm3 (73–116 cu in) skull capacity

- Lack of a protruding chin (mental protuberance; although later specimens possess a slight protuberance)

- Crest on the mastoid process behind the ear opening

- No groove on canine teeth

- A retromolar space posterior to the third molar

- Bony projections on the sides of the nasal opening, projecting nose

- Distinctive shape of the bony labyrinth in the ear

- Larger mental foramen in mandible for facial blood supply

- Sub-cranial

- Considerably more robust, stronger build

- Long collar bones, wider shoulders

- Barrel-shaped rib cage

- Short, bowed shoulder blades

- Larger round finger tips

- Large kneecaps

- Thick, bowed shaft of the thigh bones, bowed femur

- Short shinbones and calf bones, shorter torus proportionally longer legs

- Long, gracile pelvic pubis (superior pubic ramus)

Genome

Previous investigations concentrated on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which, owing to strictly matrilineal inheritance and subsequent vulnerability to genetic drift, is of limited value to disprove interbreeding. More recent investigations have access to growing strings of sequenced nuclear (nDNA). The ongoing scientific efforts may be conceptually divided into:

- sequencing recovered remains of aDNA

- present day DNA (mtDNA, nDNA) sequencing to find differences in ancient signals in subpopulation gene pools.

aDNA

In July 2006, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and 454 Life Sciences announced that they would be sequencing the Neanderthal genome over the next two years. This genome is very likely to be roughly the size of the human genome, three-billion base pairs, and probably shares most of its genes. It is thought a comparison will expand understanding of Neanderthals as well as the evolution of humans and human brains.[33]

Svante Pääbo has tested more than 70 Neanderthal specimens and found only one which had enough DNA to sample. Preliminary DNA sequencing from a 38,000-year-old bone fragment of a femur found at Vindija cave, Croatia, in 1980 shows that Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens share about 99.5% of their DNA. From mtDNA analysis estimates, the two species shared a common ancestor about 500,000 years ago. An article[34] appearing in the journal Nature has calculated the species diverged about 516,000 years ago, whereas fossil records show a time of about 400,000 years ago. Scientists hope the DNA records will answer the question of whether there was interbreeding among the species.[35] A 2007 study pushes the point of divergence back to around 800,000 years ago.[36]

Edward Rubin of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California states that recent genome testing of Neanderthals suggests human and Neanderthal DNA are some 99.5% to nearly 99.9% identical.[37][38]

On November 16, 2006, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory issued a press release suggesting that Neanderthals and ancient humans probably did not interbreed.[39] Edward M. Rubin, director of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Joint Genome Institute (JGI), sequenced a fraction (0.00002) of genomic nuclear DNA (nDNA) from a 38,000-year-old Vindia Neanderthal femur bone. They calculated the common ancestor to be about 353,000 years ago, and a complete separation of the ancestors of the species about 188,000 years ago. Their results show the genomes of modern humans and Neanderthals are at least 99.5% identical, but despite this genetic similarity, and despite the two species having coexisted in the same geographic region for thousands of years, Rubin and his team did not find any evidence of any significant crossbreeding between the two. Rubin said, "While unable to definitively conclude that interbreeding between the two species of humans did not occur, analysis of the nuclear DNA from the Neanderthal suggests the low likelihood of it having occurred at any appreciable level."[40]

A main proponent of the interbreeding hypothesis is Erik Trinkaus of Washington University. In a 2006 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Trinkaus and his co-authors report a possibility that Neanderthals and humans did interbreed. The study claims to settle the extinction controversy; according to researchers, the human and neanderthal populations blended together through sexual reproduction. Trinkaus states, "Extinction through absorption is a common phenomenon,"[22] and "From my perspective, the replacement vs. continuity debate that raged through the 1990s is now dead."[41] Trinkaus thinks he sees evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans in some fossils like the 24,500-year-old skeleton of a child found in Lagar Velho in Portugal.

Recently, Richard E. Green et al. from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology published the full sequence of Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and suggested that "Neandertals had a long-term effective population size smaller than that of modern humans."[42] While reporting in Nature Journal about the same publication, James Morgan asserted that the mtDNA sequence contained clues that Neanderthals lived in "small and isolated populations, and probably did not interbreed with their human neighbours."[43][44]

Key dates

- 1829: Neanderthal skulls were discovered in Engis, Belgium.

- 1848: Skull of an ancient human was found in Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar. Its significance was not realised at the time.

- 1856: Johann Karl Fuhlrott first recognised the fossil called “Neanderthal man”, discovered in Neanderthal, a valley near Mettmann in what is now North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

- 1880: The mandible of a Neanderthal child was found in a secure context and associated with cultural debris, including hearths, Mousterian tools, and bones of extinct animals.

- 1886: two nearly perfect skeletons of a man and woman were found at Spy, Belgium at the depth of 16 ft. with numerous Mousterian-type implements.

- 1899: Hundreds of Neanderthal bones were described in stratigraphic position in association with cultural remains and extinct animal bones.

- 1908: A nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton was discovered in association with Mousterian tools and bones of extinct animals.

- 1953–1957: Ralph Solecki uncovered nine Neanderthal skeletons in Shanidar Cave in northern Iraq.

- 1975: Erik Trinkaus’s study of Neanderthal feet confirmed that they walked like modern humans.

- 1987: Thermoluminescence results from Israeli fossils date Neanderthals at Kebara to 60,000 BP and humans at Qafzeh to 90,000 BP. These dates were confirmed by Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) dates for Qafzeh (90,000 BP) and Es Skhul (80,000 BP).

- 1991: ESR dates showed that the Tabun Neanderthal was contemporaneous with modern humans from Skhul and Qafzeh.

- 1997: Matthias Krings et al. are the first to amplify Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) using a specimen from Feldhofer grotto in the Neander valley.[45]

- 2000: Igor Ovchinnikov, Kirsten Liden, William Goodman et al. retrieved DNA from a Late Neanderthal (29,000 BP) infant from Mezmaikaya Cave in the Caucasus.[46]

- 2005: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology launched a project to reconstruct the Neanderthal genome.

- 2006: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology announced that it planned to work with Connecticut-based 454 Life Sciences to reconstruct the Neanderthal genome.

- 2009: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology announced that the "first draft" of a complete Neanderthal genome is completed.[47]

Language

The idea that Neanderthals lacked complex language was widespread,[48] despite concerns about the accuracy of reconstructions of the Neanderthal vocal tract, until 1983, when a Neanderthal hyoid bone was found at the Kebara Cave in Israel. The hyoid is a small bone which connects the musculature of the tongue and the larynx, and by bracing these structures against each other, allows a wider range of tongue and laryngeal movements than would otherwise be possible. The presence of this bone implies that speech was anatomically possible. The bone which was found is virtually identical to that of modern humans.[49]

The morphology of the outer and middle ear of Neanderthal ancestors, Homo heidelbergensis, found in Spain, suggests they had an auditory sensitivity similar to modern humans and very different from chimpanzees. They were probably able to differentiate between many different sounds.[50]

Neurological evidence for potential speech in neanderthalensis exists in the form of the hypoglossal canal. The canal of neanderthalensis is the same size or larger than in modern humans, which are significantly larger than the canal of australopithecines and modern chimpanzees. The canal carries the hypoglossal nerve, which controls the muscles of the tongue. This indicates that neanderthalensis had vocal capabilities similar to modern humans.[51] A research team from the University of California, Berkeley, led by David DeGusta, suggests that the size of the hypoglossal canal is not an indicator of speech. His team's research, which shows no correlation between canal size and speech potential, shows there are a number of extant non-human primates and fossilized australopithecines which have equal or larger hypoglossal canal.[52]

Another anatomical difference between Neanderthals and modern humans is their lack of a mental protuberance (the point at the tip of the chin). This may be relevant to speech as the mentalis muscle contributes to moving the lower lip and is used to voice a bilabial click. While some Neanderthal individuals do possess a mental protuberance, their chins never show the inverted T-shape of modern humans.[53] In contrast, some Neanderthal individuals show inferior lateral mental tubercles (little bumps at the side of the chin).

A recent extraction of DNA from Neanderthal bones indicates that Neanderthals had the same version of the FOXP2 gene as modern humans. This gene is known to play a role in human language.[54]

Steven Mithen (2006) proposes that the Neanderthals had an elaborate proto-linguistic system of communication which was more musical than modern human language, and which predated the separation of language and music into two separate modes of cognition.[55]

Tools

Neanderthal and Middle Paleolithic archaeological sites show a smaller and different toolkit than those which have been found in Upper Paleolithic sites, which were perhaps occupied by modern humans which superseded them. Fossil evidence indicating who may have made the tools found in Early Upper Paleolithic sites is still missing.

Neanderthals are thought to have used tools of the Mousterian class, which were often produced using soft hammer percussion, with hammers made of materials like bones, antlers, and wood, rather than hard hammer percussion, using stone hammers. A result of this is that their bone industry was relatively simple. However, there is good evidence that they routinely constructed a variety of stone implements. Neanderthal (Mousterian) tools most often consisted of sophisticated stone-flakes, task-specific hand axes, and spears. Many of these tools were very sharp. There is also good evidence that they used a lot of wood, objects which are unlikely to have been preserved until today.[56]

Also, while they had weapons, whether they had implements which were used as projectile weapons is controversial. They had spears, made of long wooden shafts with spearheads firmly attached, but they are thought by some to have been thrusting spears.[57] Still, a Levallois point embedded in a vertebra shows an angle of impact suggesting that it entered by a "parabolic trajectory" suggesting that it was the tip of a projectile.[58] Moreover, a number of 400,000 year old wooden projectile spears were found at Schöningen in northern Germany. These are thought to have been made by the Neanderthal's ancestors, Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis. Generally, projectile weapons are more commonly associated with H. sapiens. The lack of projectile weaponry is an indication of different sustenance methods, rather than inferior technology or abilities. The situation is identical to that of native New Zealand Māori — modern Homo sapiens, who also rarely threw objects, but used spears and clubs instead.[59]

Although much has been made of the Neanderthals' burial of their dead, their burials were less elaborate than those of anatomically modern humans. The interpretation of the Shanidar IV burials as including flowers, and therefore being a form of ritual burial,[60] has been questioned.[61] On the other hand, five of the six flower pollens found with Shanidar IV are known to have had 'traditional' medical uses, even among relatively recent 'modern' populations. In some cases Neanderthal burials include grave goods, such as bison and aurochs bones, tools, and the pigment ochre.

Neanderthals also performed many sophisticated tasks which are normally associated only with humans. For example, it is known that they controlled fire, constructed complex shelters, and skinned animals. A trap excavated at La Cotte de St Brelade in Jersey gives testament to their intelligence and success as hunters.[62]

Particularly intriguing is a hollowed-out bear femur with holes which may have been deliberately bored into it. This bone was found in western Slovenia in 1995, near a Mousterian fireplace, but its significance is still a matter of dispute. Some paleoanthropologists have hypothesized that it was a flute, while others believe it was created by accident through the chomping action of another bear. See: Divje Babe flute.

Pendants and other jewelry showing traces of ochre dye and of deliberate grooving have also been found[63] with later finds, particularly in France but whether or not they were created by Neanderthals or traded to them by Cro-Magnons is a matter of controversy.

Habitat and range

Early Neanderthals lived in the Last Glacial age for a span of about 100,000 years. Because of the damaging effects which the glacial period had on the Neanderthal sites, not much is known about the early species. Countries where their remains are known include Portugal, Ukraine, France[64] and Spain, Britain,[62] Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, Greece,[65] Iraq, Israel, Iran, Romania and Russia.

Classic Neanderthal fossils have been found over a large area, from northern Germany to Israel and Mediterranean countries like Spain and Italy in the south and from England and Portugal in the west to Uzbekistan in the east. This area probably was not occupied all at the same time; the northern border of their range in particular would have contracted frequently with the onset of cold periods. On the other hand, the northern border of their range as represented by fossils may not be the real northern border of the area they occupied, since Middle-Palaeolithic looking artifacts have been found even further north, up to 60° on the Russian plain.[66] Recent evidence has extended the Neanderthal range by about 1,250 miles (2,010 km) east into southern Siberia's Altay Mountains.[67][68]

Fate

Possible hypotheses for the fate of Neanderthals include the following:

- Neanderthals were a separate species from modern humans, did not interbreed, and became extinct (due to climate change or interaction with humans) and were replaced by early modern humans traveling from Africa.[69] Competition from H. sapiens probably contributed to Neanderthal extinction.[70] Jared Diamond has suggested a scenario of violent conflict.[71]

- Neanderthals were a contemporary subspecies which incidentally bred with Homo sapiens and disappeared through absorption (see Neanderthal interaction with Cro-Magnons)

- Neanderthals never split from Homo sapiens and most of their populations transformed into anatomically modern humans between 50-30 thousand years ago (see Multiregional origin of modern humans).

The anthropogeneses according to hypotheses #1 and #2 are basically in agreement with the Recent African origin of modern humans or RAO hypothesis.

Extinction

According to the oldest view (#1), modern humans (Homo sapiens) began replacing Neanderthals around 45,000 years ago, as the Cro-Magnon people appeared in Europe, pushing populations of Neanderthals into regional pockets, such as modern-day Croatia, Iberia, and the Crimean peninsula,[clarification needed] where they held on for thousands of years. The last traces of Mousterian culture (without human specimens) have been found in Gorham's Cave on the remote south-facing coast of Gibraltar, dated 30,000 to 24,500 years ago. Proponents of this model believe that modern humans and the neanderthals were separate species that were not interfertile. They cite the following evidence:

- The Neanderthals and Modern humans were contemporaneous species. The two species maintained distinct morphologies over hundreds of thousands of years. On a number of occasions the habitats of modern humans and the Neanderthals overlapped. However, despite this overlap, the respective morphologies remained distinct based on the available fossil record.[72]

- For example, remains associated with modern human anatomy have been found at Qafzeh in Israel dating to 90,000 years ago. These remains predate Neanderthal remains such as those at Kebara Cave, also in Israel, by about 30,000 years. Since Neanderthals appear after modern humans, it is unlikely that these modern humans evolved from the Neanderthals.[73]

- No incontrovertible fossils that demonstrate intermediate characteristics between modern humans and Neanderthals have been found.[72]

- Studies using non-recombinant DNA point to a recent African origin of Europeans. Mitochondrial DNA studies of a Neanderthal specimen revealed modern humans and Neanderthals last shared a common ancestor circa 600 000 years ago.[74][75]

- Currently all European mtDNA lineages trace back to African lineages. Haplogroup N (mtDNA), the ancestral haplogroup for all Europeans, is thought to have emerged in East Africa 60–80,000 years ago.

- A study conducted in 2008 of 28,000 year old Cro-Magnon remains found that the mtDNA haplogroup of the specimen was a common haplogroup in contemporary Europeans. The haplogroup differed substantially from known Neanderthal mtDNA sequences.[76]

- A recent statistical simulation found either no or insignificant admixing between modern humans and Neanderthals.[77] Another mtDNA analysis showed no evidence for Neanderthal contributions to the gene pool of modern humans.[78] The authors of the study concede this does not exclude Neanderthal contributions of other genes. They nevertheless argue other genetic and morphological data also suggest little or no Neanderthal contribution.

- The most recent patrilineal ancestor of all living humans (traced via Y-chromosome inheritance), Y-chromosomal Adam, is estimated to have lived in Africa 60,000 years ago.

Interbreeding hypotheses

The validity of such an extensive period of cornered Neanderthal groups is recently questioned. There is no longer certainty regarding the identity of the humans who produced the Aurignacian culture, even though the presumed westward spread of anatomically modern humans (AMHs) across Europe is still based on the controversial first dates of the Aurignacian. Currently, the oldest European anatomically modern Homo sapiens is represented by a robust modern human mandible discovered at Pestera cu Oase (south-west Romania), dated to 34–36 thousand years ago. Human skeletal remains from the German site of Vogelherd, so far regarded the best association between anatomically modern Homo sapiens and Aurignacian culture, were revealed to represent intrusive Neolithic burials into the Aurignacian levels and subsequently all the key Vogelherd fossils are now dated to 3.9–5.0 thousand years ago instead.[79] As for now, the expansion of the first anatomically modern humans into Europe can not be located by diagnostic and well-dated anatomically modern human fossils "west of the Iron Gates of the Danube" before 32 thousand years ago.[80]

Consequently, the exact nature of biological and cultural interactions between Neanderthals and other human groups between 50 and 30 thousand years ago is currently hotly contested.[81] A new proposal resolves the issue by taking the Gravettians rather than the Aurignacians as the anatomically modern humans which contributed to the Eurasian genetic pool after 30 thousand years ago.[81] Correspondingly, the human skull fragment found at the Elbe River bank at Hahnöfersand near Hamburg was once radiocarbon dated to 36,000 years ago and seen as possible evidence for the intermixing of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. It is now dated to the more recent Mesolithic.[82]

Modern human findings in Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal of 24,500 years ago, allegedly featuring Neanderthal admixtures, have been published.[83] However the interpretation of the Portuguese specimen is disputed.[72]

In another study, researchers have recently found in Pestera Muierii, Romania, remains of European humans from 30 thousand years ago who possessed mostly diagnostic "modern" anatomical features, but also had distinct Neanderthal features not present in ancestral modern humans in Africa, including a large bulge at the back of the skull, a more prominent projection around the elbow joint, and a narrow socket at the shoulder joint. Analysis of one skeleton's shoulder showed that these humans, like Neanderthal, did not have the full capability for throwing spears.[22]

The paleontological analysis of modern human emergence in Europe has been shifting from considerations of the Neanderthals to assessments of the biology and chronology of the earliest modern humans in western Eurasia. This focus, involving morphologically modern humans before 28,000 years ago shows accumulating evidence that they present a variable mosaic of derived modern human, archaic human, and Neanderthal features.[84][80][85] Studies of fossils from the upper levels of the Sima de las Palomas, Murcia, Spain, dated to 40,000 years ago, establish the late persistence of Neanderthals in Iberia. This reinforces the conclusion that the Neanderthals were not merely swept away by advancing modern humans. In addition, the Palomas Neanderthals variably exhibit a series of modern human features rare or absent in earlier Neanderthals. Either they were evolving on their own towards the modern human pattern, or more likely, they had contact with early modern humans around the Pyrenees. If the latter, it implies that the persistence of the Middle Paleolithic in Iberia was a matter of choice, and not cultural retardation.[86]

Cannibalism or ritual defleshing?

Neanderthals hunted large animals, such as the mammoth. Stone-tipped wooden spears were used for hunting and stone knives and poleaxes were used for butchering the animals or as weapons. However, they are believed to have practiced cannibalism, or ritual defleshing. This hypothesis has been represented after researchers found marks on Neanderthal bones similar to the bones of a dead deer butchered by Neanderthals.

Intentional burial and the inclusion of grave goods are the most typical representations of ritual behavior in the Neanderthals and denote a developing ideology. However, another much debated and controversial manifestation of this ritual treatment of the dead comes from the evidence of cut-marks on the bone which has 'historically been viewed' as evidence of ritual defleshing.

Neanderthal bones from various sites (Combe-Grenal and Abri Moula in France, Krapina in Croatia and Grotta Guattari in Italy) have all been cited as bearing cut marks made by stone tools.[87] However, results of technological tests reveal varied causes.

Re-evaluation of these marks using high-powered microscopes, comparisons to contemporary butchered animal remains and recent ethnographic cases of excarnation mortuary practises have shown that perhaps this was a case of ritual defleshing.

- At Grotta Guattari, the apparently purposefully widened base of the skull (for access to the brains) has been shown to be caused by carnivore action, with hyena tooth marks found on the skull and mandible.

- According to some studies, fragments of bones from Krapina show marks which are similar to those seen on bones from secondary burials at a Michigan ossuary (14th century AD) and are indicative of removing the flesh of a partially decomposed body.

- According to others, the marks on the bones found at Krapina are indicative of defleshing, although whether this was for nutritional or ritual purposes cannot be determined with certainty.[88]

- Analysis of bones from Abri Moula in France does seem to suggest cannibalism was practiced here. Cut-marks are concentrated in places expected in the case of butchery, instead of defleshing. Additionally the treatment of the bones was similar to that of roe deer bones, assumed to be food remains, found in the same shelter.[89]

The evidence indicating cannibalism would not distinguish Neanderthals from modern Homo sapiens. Ancient and existing Homo sapiens are known to have practiced cannibalism (e.g. the Korowai) and/or mortuary defleshing (e.g. the sky burial of Tibet).

Grooves in bones are hypothesized to be cuts by Neanderthal tools, not animal teeth. The chances of them being random, as some writers attributing them to animals have proposed, is debated.

Pathology

Within the west Asian and European record there are five broad groups of pathology or injury noted in Neanderthal skeletons.

Fractures

Neanderthals seemed to suffer a high frequency of fractures, especially common on the ribs (Shanidar IV, La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 ‘Old Man’), the femur (La Ferrassie 1), fibulae (La Ferrassie 2 and Tabun 1), spine (Kebara 2) and skull (Shanidar I, Krapina, Sala 1). These fractures are often healed and show little or no sign of infection, suggesting that injured individuals were cared for during times of incapacitation. The pattern of fractures, along with the absence of throwing weapons, suggests that they may have hunted by leaping onto their prey and stabbing or even wrestling it to the ground.[90]

Trauma

Particularly related to fractures are cases of trauma seen on many skeletons of Neanderthals. These usually take the form of stab wounds, as seen on Shanidar III, whose lung was probably punctured by a stab wound to the chest between the 8th and 9th ribs. This may have been an intentional attack or merely a hunting accident; either way the man survived for some weeks after his injury before being killed by a rock fall in the Shanidar cave. Other signs of trauma include blows to the head (Shanidar I and IV, Krapina), all of which seemed to have healed, although traces of the scalp wounds are visible on the surface of the skulls.

Degenerative disease

Arthritis is particularly common in the older Neanderthal population, specifically targeting areas of articulation such as the ankle (Shanidar III), spine and hips (La Chapelle-aux-Saints ‘Old Man’), arms (La Quina 5, Krapina, Feldhofer) knees, fingers and toes. This is closely related to degenerative joint disease, which can range from normal, use-related degeneration to painful, debilitating restriction of movement and deformity and is seen in varying degree in the Shanidar skeletons (I–IV).

Hypoplastic disease

Dental enamel hypoplasia is an indicator of stress during the development of teeth and records in the striations and grooves in the enamel periods of food scarcity, trauma or disease. A study of 669 Neanderthal dental crowns showed that 75% of individuals suffered some degree of hypoplasia and that nutritional deficiencies were the main cause of hypoplasia and eventual tooth loss. All particularly aged skeletons show evidence of hypoplasia and it is especially evident in the Old Man of La Chapelle-aux-Saints and La Ferrassie 1 teeth.

Infection

Evidence of infections on Neanderthal skeletons is usually visible in the form of lesions on the bone, which are created by systematic infection on areas closest to the bone. Shanidar I has evidence of the degenerative lesions as does La Ferrassie 1, whose lesions on both femora, tibiae and fibulae are indicative of a systemic infection or carcinoma (malignant tumour/cancer).

Childhood

Neanderthal children might have grown faster than modern human children. Modern humans have the slowest body growth of any mammal during childhood (the period between infancy and puberty) with lack of growth during this period being made up later in an adolescent growth spurt.[91][92][93] The possibility that Neanderthal childhood growth was different was first raised in 1928 by the excavators of the Mousterian rock-shelter of a Neanderthal juvenile.[94] Arthur Keith in 1931 wrote, "Apparently Neanderthal children assumed the appearances of maturity at an earlier age than modern children."[95] The earliness of body maturation can be inferred from the maturity of a juvenile's fossile remains and estimated age of death. The age at which juveniles die can be indirectly inferred from their tooth morphology, development and emergence. This has been argued to both support[96] and question[97] the existence of a maturation difference between Neanderthals and modern humans. Since 2007 tooth age can be directly calculated using the noninvasive imaging of growth patterns in tooth enamel by means of x-ray synchrotron microtomography.[98] This research supports the existence of a much quicker physical development in Neanderthals than in modern human children.[99] The x-ray synchrotron microtomography study of early H. sapiens sapiens argues that this difference existed between the two species as far back as 160,000 years before present.[100]

Popular culture

In popular idiom the word neanderthal is sometimes used as an insult, to suggest that a person combines a deficiency of intelligence and an attachment to brute force, as well as perhaps implying the person is old fashioned or attached to outdated ideas, much in the same way as "dinosaur" is also used. Although they are frequently characterized in this manner, research showing Neanderthals were as intelligent as contemporaneous Homo sapiens, with early stone tool technologies of comparable efficiency, is debunking long-held beliefs.[101]

Counterbalancing this are sympathetic literary portrayals of Neanderthals, as in the novel The Inheritors by William Golding, Isaac Asimov's The Ugly Little Boy, and Jean M. Auel's Earth's Children series, though Auel repeatedly compares Neanderthals to modern humans unfavorably within the series, showing them to be less advanced in nearly every facet of their lives. Instead she gives them access to a 'race memory' and uses it to explain both their cultural richness and eventual stagnation. A more serious treatment is offered by Finnish palaeontologist Björn Kurtén, in several works including Dance of the Tiger, and British psychologist Stan Gooch in his hybrid-origin theory of humans. The Neanderthal Parallax, a trilogy of science fiction novels dealing with neanderthals, written by Robert J. Sawyer, explores a scenario where neanderthals are seen as a distinct species from humans and survive in a parallel universe version of earth. The novels explore what happens when they, having developed a sophisticated technological culture of their own, open a portal to this version of the earth. The three novels are titled Hominids, Humans, and Hybrids, respectively, and together form essentially one story.

In the Thursday Next series of novels by Jasper Fforde, a small population of Neanderthals were re-created in modern Britain by advanced cloning techniques in the later years of the twentieth century. These fictional Neanderthals have equivalent intelligence to normal humans, but have a radically different culture in which aggression and competition are virtually unthinkable.

See also

- Abrigo do Lagar Velho — More about "the Lapedo child"

- Almas: wild man of Mongolia

- Altamura Man

- Biological anthropology

- Caveman

- Homo floresiensis

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

- List of Neanderthal sites

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

- Neanderthal genome project

- Neanderthal extinction hypotheses

- Neanderthal Museum

- Pleistocene megafauna

Footnotes

- ^ Tattersall I, Schwartz JH (1999). "Hominids and hybrids: the place of Neanderthals in human evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7117–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7117. PMC 33580. PMID 10377375. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ J. L. Bischoff; et al. (2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350 kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500 kyr: New Radiometric Dates". J. Archaeol. Sci. 30 (30): 275. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Viegas, Jennifer (June 23, 2008). "Last Neanderthals Were Smart, Sophisticated". Discovery Channel. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Duarte C, Maurício J, Pettitt PB, Souto P, Trinkaus E, van der Plicht H, Zilhão J (1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in Iberia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7604–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Finlayson, C; Pacheco, Fg; Rodríguez-Vidal, J; Fa, Da; Gutierrez, López, Jm; Santiago, Pérez, A; Finlayson, G; Allue, E; Baena, Preysler, J; Cáceres, I; Carrión, Js; Fernández, Jalvo, Y; Gleed-Owen, Cp; Jimenez, Espejo, Fj; López, P; López, Sáez, Ja; Riquelme, Cantal, Ja; Sánchez, Marco, A; Guzman, Fg; Brown, K; Fuentes, N; Valarino, Ca; Villalpando, A; Stringer, Cb; Martinez, Ruiz, F; Sakamoto, T (2006). "Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe". Nature. 443 (7113): 850–3. doi:10.1038/nature05195. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16971951.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stanyon, R.; et al. (1993). "Cranial Capacity in Hominid Evolution". Human Evolution. 8 (3): 205–216. doi:10.1007/BF02436715.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ "Science & Nature — Wildfacts — Neanderthal". BBC. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Helmuth H (1998). "Body height, body mass and surface area of the Neanderthals". Zeitschrift Für Morphologie Und Anthropologie. 82 (1): 1–12. PMID 9850627.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Text "2008-05-26" ignored (help); Text "mdy" ignored (help)}} - ^ Richards MP, Pettitt PB, Trinkaus E, Smith FH, Paunović M, Karavanić I (2000). "Neanderthal diet at Vindija and Neanderthal predation: the evidence from stable isotopes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (13): 7663–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.120178997. PMC 16602. PMID 10852955.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frabetti, P (2004). "On the narrow dip structure at 1.9 GeV/c2 in diffractive photoproduction". Physics Letters B. 578: 290. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2003.10.071.

- ^ Plagnol, V; Wall, Jd (2006). "Possible ancestral structure in human populations". PLoS Genetics. 2 (7): e105. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020105. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 1523253. PMID 16895447.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Harvati K, Frost SR, McNulty KP (2004). "Neanderthal taxonomy reconsidered: implications of 3D primate models of intra- and interspecific differences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (5): 1147–52. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308085100. PMC 337021. PMID 14745010.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Modern humans, Neanderthals shared earth for 1,000 years". ABC News (Australia). September 1, 2005. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ Hedges SB (2000). "Human evolution. A start for population genomics". Nature. 408 (6813): 652–3. doi:10.1038/35047193. PMID 11130051.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Homo neanderthalensis". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Bischoff, J (2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30: 275. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834.

- ^ Arsuaga JL, Martínez I, Gracia A, Lorenzo C (1997). "The Sima de los Huesos crania (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). A comparative study". Journal of Human Evolution. 33 (2–3): 219–81. doi:10.1006/jhev.1997.0133. PMID 9300343.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kreger, C. David. "Homo neanderthalensis". ArchaeologyInfo.com. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Mcdermott, F; Grün, R; Stringer, Cb; Hawkesworth, Cj (1993). "Mass-spectrometric U-series dates for Israeli Neanderthal/early modern hominid sites". Nature. 363 (6426): 252–5. doi:10.1038/363252a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8387643.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rincon, Paul (September 13, 2006). "Neanderthals' 'last rock refuge'". BBC News. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Conard, Nj; Grootes, Pm; Smith, Fh (2004). "Unexpectedly recent dates for human remains from Vogelherd". Nature. 430 (6996): 198–201. doi:10.1038/nature02690. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15241412.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Hayes, Jacqui (November 2, 2006). "Humans and Neanderthals interbred". Cosmos. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- ^ Higham T, Ramsey CB, Karavanić I, Smith FH, Trinkaus E (2006). "Revised direct radiocarbon dating of the Vindija G1 Upper Paleolithic Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (3): 553–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510005103. PMC 1334669. PMID 16407102.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Helmuth H (1998). "Body height, body mass and surface area of the Neanderthals". Zeitschrift Für Morphologie Und Anthropologie. 82 (1): 1–12. PMID 9850627.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Neanderthal". BBC. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Laleuza-Fox, Carles (2007-10-25). "A Melanocortin 1 Receptor Allele Suggests Varying Pigmentation Among Neanderthals". Science. 318: 1453. doi:10.1126/science.1147417. PMID 17962522.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rincon, Paul (October 25, 2007). "Neanderthals 'were flame-haired'". BBC News. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (March 10, 2005). "Scientists Build 'Frankenstein' Neanderthal Skeleton". LiveScience. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Gunz, P; Harvati, K (2007). "The Neanderthal "chignon": variation, integration, and homology" (PDF). Journal of human evolution. 52 (3): 262–74. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.010. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 17097133.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.pajamacore.org/writings/origins.php[dead link]

- ^ Bower, Bruce (April 11, 1992). "Neanderthals to investigators: can we talk? - vocal abilities in pre-historic humans". Science News.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Arensburg, B; Schepartz, La; Tillier, Am; Vandermeersch, B; Rak, Y (1990). "A reappraisal of the anatomical basis for speech in Middle Palaeolithic hominids". American journal of physical anthropology. 83 (2): 137–46. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330830202. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 2248373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moulson, Geir (July 20, 2006). "Neanderthal genome project launches". MSNBC. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Green RE, Krause J, Ptak SE; et al. (2006). "Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA". Nature. 444 (7117): 330–6. doi:10.1038/nature05336. PMID 17108958.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wade, Nicholas (November 15, 2006). "New Machine Sheds Light on DNA of Neanderthals". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Pennisi E (2007). "Ancient DNA. No sex please, we're Neandertals". Science. 316 (5827): 967. doi:10.1126/science.316.5827.967a. PMID 17510332.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Neanderthal bone gives DNA clues". CNN. Associated Press. November 16, 2006. Archived from the original on November 18, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Than, Ker (November 15, 2006). "Scientists decode Neanderthal genes". MSNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Neanderthal Genome Sequencing Yields Surprising Results And Opens A New Door To Future Studies" (Press release). Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. November 16, 2006. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ Hayes, Jacqui (November 15, 2006). "DNA find deepens Neanderthal mystery". Cosmos. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Mundell, E. J. (October 30, 2006). "Modern Humans, Neanderthals May Have Interbred". AllRefer. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Green, Re; Malaspinas, As; Krause, J; Briggs, Aw; Johnson, Pl; Uhler, C; Meyer, M; Good, Jm; Maricic, T; Stenzel, U; Prüfer, K; Siebauer, M; Burbano, Ha; Ronan, M; Rothberg, Jm; Egholm, M; Rudan, P; Brajković, D; Kućan, Z; Gusić, I; Wikström, M; Laakkonen, L; Kelso, J; Slatkin, M; Pääbo, S (2008). "A complete Neandertal mitochondrial genome sequence determined by high-throughput sequencing". Cell. 134 (3): 416–26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.021. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 2602844. PMID 18692465.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans PD, Mekel-Bobrov N, Vallender EJ, Hudson RR, Lahn BT (2006). "Evidence that the adaptive allele of the brain size gene microcephalin introgressed into Homo sapiens from an archaic Homo lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (48): 18178–83. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606966103. PMC 1635020. PMID 17090677.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans PD, Gilbert SL, Mekel-Bobrov N, Vallender EJ, Anderson JR, Vaez-Azizi LM, Tishkoff SA, Hudson RR, Lahn BT (2005). "Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size, continues to evolve adaptively in humans". Science. 309 (5741): 1717–20. doi:10.1126/science.1113722. PMID 16151009.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krings, M; Stone, A; Schmitz, Rw; Krainitzki, H; Stoneking, M; Pääbo, S (1997). "Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans". Cell. 90 (1): 19–30. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 9230299.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ovchinnikov, Iv; Götherström, A; Romanova, Gp; Kharitonov, Vm; Lidén, K; Goodwin, W (2000). "Molecular analysis of Neanderthal DNA from the northern Caucasus". Nature. 404 (6777): 490–3. doi:10.1038/35006625. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10761915.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morgan, James (February 12, 2009). "Neanderthals 'distinct from us'". BBC News. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ Lieberman, Philip (1971). "On the Speech of Neanderthal Man". Linguistic Inquiry. 2 (2): 203–222. doi:10.2307/4177625. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Arensburg B, Tillier AM, Vandermeersch B, Duday H, Schepartz LA, Rak Y (1989). "A Middle Palaeolithic human hyoid bone". Nature. 338 (6218): 758–60. doi:10.1038/338758a0. PMID 2716823.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martínez I, Rosa M, Arsuaga JL, Jarabo P, Quam R, Lorenzo C, Gracia A, Carretero JM, Bermúdez de Castro JM, Carbonell E (2004). "Auditory capacities in Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (27): 9976–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403595101. PMC 454200. PMID 15213327.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kay RF, Cartmill M, Balow M (1998). "The hypoglossal canal and the origin of human vocal behavior". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (9): 5417–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.9.5417. PMC 20276. PMID 9560291.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeGusta D, Gilbert WH, Turner SP (1999). "Hypoglossal canal size and hominid speech". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (4): 1800–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.4.1800. PMC 15600. PMID 9990105.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jeffrey Schwartz, Ian Tattersall (2000). "The human chin revisited: What is it, and who has it?". Journal of Human Evolution. 38: 367–409. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0339.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wade, Nicholas (October 19, 2007). "Neanderthals Had Important Speech Gene, DNA Evidence Shows". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Mithen, Steven J. (2006). The singing neanderthals: the origins of music, language, mind, and body. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02192-4. OCLC 62090869.[page needed]

- ^ Pettitt, Paul (2000). "Odd man out: Neanderthals and modern humans". British Archeology. 51. ISSN 1357-4442. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Churchill, Steven E. (2002). "Of assegais and bayonets: Reconstructing prehistoric spear use". Evolutionary Anthropology. 11 (5): 185–186. doi:10.1002/evan.10027.

- ^ Boëda, Eric (1999). "A Levallois point embedded in the vertebra of a wild ass (Equus africanus): hafting, projectiles and Mousterian hunting weapons". Antiquity. 73 (280): 394–402. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schwimmer, E. G. (1961). "Warfare of the Maori". Te Ao Hou: the New World. 36: 51–53. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Solecki, Ralph S. (1975). "Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq". Science. 190 (4217): 880–881. Bibcode:1975Sci...190..880S.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sommer, J. D. (1999). "The Shanidar IV 'Flower Burial': a Re-evaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 9 (1): 127–129. ISSN 0959-7743.

- ^ a b Dargie, Richard (2007). A History of Britain. London: Arcturus. p. 9. ISBN 9780572033422. OCLC 124962416.

- ^ Kuhn SL, Stiner MC, Reese DS, Güleç E (2001). "Ornaments of the earliest Upper Paleolithic: new insights from the Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (13): 7641–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.121590798. PMC 34721. PMID 11390976.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hammond, Norman (September 1, 2005). "Neanderthals and modern man shared a cave". The Times. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ "Ancient tooth provides evidence of Neanderthal movement" (Press release). Durham University. February 11, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Pavlov P, Roebroeks W, Svendsen JI (2004). "The Pleistocene colonization of northeastern Europe: a report on recent research". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1–2): 3–17. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.002. PMID 15288521.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wade, Nicholas (October 2, 2007). "Fossil DNA Expands Neanderthal Range". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Ravilious, Kate (October 1, 2007). "Neandertals Ranged Much Farther East Than Thought". National Geographic Society. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ "First genocide of human beings occurred 30,000 years ago". Pravda. October 24, 2007. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ McKie, Robin (May 17, 2009). "How Neanderthals met a grisly fate: devoured by humans". The Observer. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Diamond, Jared M. (1992). The third chimpanzee: the evolution and future of the human animal. New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-098403-1. OCLC 60088352.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Ruzicka J, Hansen EH, Ghose AK, Mottola HA (1979). "Enzymatic determination of urea in serum based on pH measurement with the flow injection method". Analytical Chemistry. 51 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1021/ac50038a011. PMID 33580.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lahr, Marta Mirazón (1996). "Discussions of Continuity versus Discontinuity". The evolution of modern human diversity: a study of cranial variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0-521-47393-4. OCLC 33131545.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Jones, Dan (November 15, 2006). "Neanderthals have genome chunk sequenced". New Scientist. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Kaplan, Karen (August 9, 2008). "Neanderthals, modern humans share ancestor, scientists say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Caramelli D, Milani L, Vai S, Modi A, Pecchioli E, Girardi M, Pilli E, Lari M, Lippi B, Ronchitelli A, Mallegni F, Casoli A, Bertorelle G, Barbujani G (2008). "A 28,000 years old Cro-Magnon mtDNA sequence differs from all potentially contaminating modern sequences". PLoS ONE. 3 (7): e2700. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002700. PMC 2444030. PMID 18628960.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Currat M, Excoffier L (2004). "Modern humans did not admix with Neanderthals during their range expansion into Europe". PLoS Biology. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Krings M, Stone A, Schmitz RW, Krainitzki H, Stoneking M, Pääbo S (1997). "Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans" (PDF). Cell. 90 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80310-4. PMID 9230299. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Conard, Nj; Grootes, Pm; Smith, Fh (2004). "Unexpectedly recent dates for human remains from Vogelherd". Nature. 430 (6996): 198–201. doi:10.1038/nature02690. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15241412.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Soficaru A, Dobos A, Trinkaus E (2006). "Early modern humans from the Pestera Muierii, Baia de Fier, Romania". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (46): 17196–201. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608443103. PMC 1859909. PMID 17085588.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Finlayson C, Carrión JS (2007). "Rapid ecological turnover and its impact on Neanderthal and other human populations". Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Personal Edition). 22 (4): 213–22. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.02.001. PMID 17300854.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Terberger, Thomas (2006). "From the First Humans to the Mesolithic Hunters in the Northern German Lowlands– Current Results and Trends". Across the western Baltic. Vordingborg, Denmark: Sydsjællands Museum. pp. 23–56. ISBN 87-983097-5-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Duarte C, Maurício J, Pettitt PB, Souto P, Trinkaus E, van der Plicht H, Zilhão J (1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in Iberia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7604–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Trinkaus E, Moldovan O, Milota S, Bîlgăr A, Sarcina L, Athreya S, Bailey SE, Rodrigo R, Mircea G, Higham T, Ramsey CB, van der Plicht J (2003). "An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (20): 11231–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.2035108100. PMC 208740. PMID 14504393.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Trinkaus E (2007). "European early modern humans and the fate of the Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (18): 7367–72. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702214104. PMC 1863481. PMID 17452632.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Washington University in St. Louis (December 8, 2008). "Late Neandertals and Modern Human Contact in Southeastern Iberia". Newswise. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Andrea Thompson (2006-12-04). "Neanderthals Were Cannibals, Study Confirms". Health SciTech. LiveScience.

- ^ Pathou-Mathis M (2000). "Neanderthal subsistence behaviours in Europe". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 10: 379–395. doi:10.1002/1099-1212(200009/10)10:5<379::AID-OA558>3.0.CO;2-4.

- ^ Defleur A, White T, Valensi P, Slimak L, Cregut-Bonnoure E (1999). "Neanderthal cannibalism at Moula-Guercy, Ardèche, France". Science. 286: 128–131. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.128. PMID 10506562.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ T.D. Berger and E. Trinkaus (1995). "Patterns of trauma among Neadertals". Journal of Archaeological Science. 22: 841–852. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(95)90013-6. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ^ Walker R, Hill K, Burger O, Hurtado AM (2006). "Life in the slow lane revisited: ontogenetic separation between chimpanzees and humans". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 129 (4): 577–83. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20306. PMID 16345067.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bogin, Barry (1997). "Evolutionary hypotheses for human childhood". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 104 (S25): 63–89. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(1997)25+<63::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Bogin, Barry (1999). Patterns of human growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56438-7. OCLC 39692257.[page needed]

- ^ Garrod, D. A. E., Buxton, L. H. D., Elliot-Smith, G., Bate, D.M. A. (1928). "Excavation of a Mousterian rock-shelter at Devil's Tower, Gibraltar". Journal of the Royal Antrhopological Institute. 58: 33–113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Keith, Arthur (1931). New discoveries relating to the antiquity of man. London: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 346. OCLC 3665578.

- ^ Ramirez Rozzi FV, Bermudez De Castro JM (2004). "Surprisingly rapid growth in Neanderthals". Nature. 428 (6986): 936–9. doi:10.1038/nature02428. PMID 15118725.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Macchiarelli R, Bondioli L, Debénath A, Mazurier A, Tournepiche JF, Birch W, Dean MC (2006). "How Neanderthal molar teeth grew". Nature. 444 (7120): 748–51. doi:10.1038/nature05314. PMID 17122777.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tafforeau P, Smith TM (2008). "Nondestructive imaging of hominoid dental microstructure using phase contrast X-ray synchrotron microtomography". Journal of Human Evolution. 54 (2): 272–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.09.018. PMID 18045654.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Smith TM, Toussaint M, Reid DJ, Olejniczak AJ, Hublin JJ (2007). "Rapid dental development in a Middle Paleolithic Belgian Neanderthal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (51): 20220–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707051104. PMC 2154412. PMID 18077342.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith TM, Tafforeau P, Reid DJ, Grün R, Eggins S, Boutakiout M, Hublin JJ (2007). "Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (15): 6128–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700747104. PMC 1828706. PMID 17372199.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Science Daily, "New Evidence Debunks 'Stupid' Neanderthal Myth"

References

- Boë, Louis-Jean (2002). "The potential Neandertal vowel space was as large as that of modern humans" (PDF). Journal of Phonetics. 30 (3): 465–484. doi:10.1006/jpho.2002.0170.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Derev'anko, Anatoliy P. (1998). The Paleolithic of Siberia: new discoveries and interpretations. Novosibirsk: Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography. ISBN 0252020529. OCLC 36461622.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jacobs, James Q. (July 4, 2000). "Neanderthal DNA Sequencing". Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- Kreger, C. David (June 30, 2000). "Homo neanderthalensis". ArchaeologyInfo.com. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- Lieberman, Philip (2007). "Current views on Neanderthal speech capabilities: A reply to Boe et al. (2002)". Journal of Phonetics. 35 (4): 552–563. doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2005.07.002.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - O'Neil, Dennis (May 12, 2009). "Evolution of Modern Humans: Neandertals". Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- Serre D, Langaney A, Chech M, Teschler-Nicola M, Paunovic M, Mennecier P, Hofreiter M, Possnert G, Pääbo S (2004). "No evidence of Neandertal mtDNA contribution to early modern humans". PLoS Biology. 2 (3): E57. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020057. PMC 368159. PMID 15024415.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Wild, Eva M. (2005). "Direct dating of Early Upper Palaeolithic human remains from Mladeč". Nature. 435: 332–5. doi:10.1038/nature03585.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) link for Nature subscribers

External links

- The Way We Are

- Link to picture of the Neanderthal trace near Gediz River in Turkey

- Link to Cross-Eyed stereoview of Neanderthal fossil cast in Chicago Field Museum

- Krapina.com — 'Krapina: The World's Largest Neanderthal Finding Site'

- Mousterian Tools of Neanderthals From Europe — World Museum of Man

- Langseth, Jared (2005). "Homo neanderthalensis". MSU EMuseum.

- "Neanderthals 'mated with modern humans'". BBC News. April 21, 1999.

- Briggs, Helen (March 27, 2003). "Neanderthals 'had hands like ours'". BBC News.

- Bringmans, Patrick (2008). "The Neanderthal Sites at Veldwezelt-Hezerwater".

- Neanderthal DNA — 'Neanderthal DNA' Includes Neanderthal mtDNA sequences

- Boyle, Alan (2006-06-06). "A Neanderthal's DNA tale". MSNBC.

- UniZH.ch — 'Comparing Neanderthals and modern humans: Neanderthals differ from anatomically modern Homo sapiens in a suite of cranial features' (cranio-facial reconstructions), Institut für Informatik der Universität Zürich

- Horan, Richard D. (2005). "How trade saved humanity from biological exclusion: an economic theory of Neanderthal extinction". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 58: 1. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2004.03.009.

- Shaw, Kl (2002). "Conflict between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies of a recent species radiation: what mtDNA reveals and conceals about modes of speciation in Hawaiian crickets" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (25): 16122–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.242585899. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 138575. PMID 12451181.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Koller, J. (2001). "High-Tech in the Middle Palaeolithic: Neandertal-Manufactured Pitch Identified". European Journal of Archaeology. 4: 385. doi:10.1177/146195710100400315.

- Sawyer GJ, Maley B (2005). "Neanderthal reconstructed". Anatomical Record. Part B, New Anatomist. 283 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1002/ar.b.20057. PMID 15761833.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ritter, Macolm (September 13, 2006). "Neanderthal Find Hints at Longer Era". CBS News.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Than, Ker (November 15, 2006). "Scientists decode Neanderthal genes". MSNBC. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - 'Bone and Stone' A digitally enhanced single frame philatelic exhibit dedicated to the Neanderthal.

- Macchiarelli, R; Bondioli, L; Debénath, A; Mazurier, A; Tournepiche, Jf; Birch, W; Dean, Mc (2006). "How Neanderthal molar teeth grew". Nature. 444 (7120): 748–51. doi:10.1038/nature05314. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17122777.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ramanan, Kharlena María (1997). "Neanderthals: A Cyber Perspective". Indiana State University. Archived from the original on March 2003.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - The Cryptid Zoo 'Neanderthals and Neanderthaloids in Cryptozoology'-modern sightings promoted by the pseudoscience of cryptozoology