National Treasure (Japan)

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of the government of Japan designates through the Agency for Cultural Affairs the most precious of the nation's tangible cultural properties as National Treasures (国宝: kokuhō). The selection criteria require outstanding quality of workmanship, a very high value for world cultural history or exceptional value for scholarship. Designated properties are generally classified as either "buildings and structures" or "fine arts and crafts". The former comprises structures that are part of castles, Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines or residences. About 20% of the 1079 National Treasures are buildings. The other 80% of National Treasures are objects such as paintings, scrolls, sutras, works of calligraphy; sculptures in wood, bronze, lacquer or stone; crafts such as pottery, lacquer ware, carvings, metalworks, swords and textiles; archaeological and historical artifacts. The listed items cover the period from ancient to early modern Japan before the Meiji period, from some of the world's oldest pottery of the Jōmon period to 19th century documents and writings. Since the designation of the Akasaka Palace in 2009, there is one 20th century National Treasure.

"National Treasure" has been used in Japan since 1897, though the term's pre-1950 and post-1950 significance is different. Before 1950 the term had been assigned to a much larger number of cultural properties, comparable to today's Important Cultural Properties and National Treasures taken together. Japan has the most comprehensive network of legislation for protecting, preserving, and classifying its cultural patrimony.[1] Typical for the Japanese preservation and restoration protection is the regard to both physical and intangible properties and their protection.[2] Direct measures aimed at protecting designated National Treasures include restrictions on alterations, transfer and export; financial support in the form of grants and tax reduction. Furthermore the Agency for Cultural Affairs provides owners with advise on restoration, administration and public display of the properties. These efforts are supplemented by laws protecting the built environment of designated structures or the techniques necessary for restoration works.

Most of Japan's National Treasures are located in Kansai which had been the region of the capital of Japan from ancient times to the 19th century. Kyoto boasts about one in five national treasures. The designated "fine arts and crafts" properties are either in private hand or in museums such as the national museums of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Nara, public prefectural and city museums or private museums. Religious items are often housed in temples and Shinto shrines or their associated museums or treasure houses.

Categories of National Treasures

The Agency for Cultural Affairs designates tangible cultural properties as National Treasures in thirteen categories based on their type. It generally distinguishes between "buildings and structures" (建造物, kenzōbutsu) and "fine arts and crafts" (美術工芸品, bijutsu kōgeihin). Each of these main categories is further subdivided in specific categories.

Buildings and structures

A total of 215 structural cultural properties have been designated as National Treasures in one of six categories.

Castles

Eight National Treasures have been designated in the category "castles" (城郭, jōkaku). They are located at four sites: Himeji Castle, Matsumoto Castle, Inuyama castle and Hikone Castle and comprise sixteen structures such as donjon, watch towers and connecting galleries. Dating to the end of the Sengoku period, from the late 16th to the first half of the 17th century, these structures present the apogee of Japanese castle construction.

Residences

The Agency for Cultural Affairs distinguishes two categories of residential architecture: "modern residences" (住居, jūkyo) from the Meiji period onward and "historical residences" (住宅, jūtaku), which date to early modern Japan and earlier, before 1867. Presently, the only modern residential National Treasure is the Akasaka Palace in Tokyo from 1909. Fourteen National Treasures from 1485 to 1657 are listed in the category of historical residences. Ten of them are located in Kyoto. The structures listed include teahouses, shoin, and guest or reception halls.

Shrines

The Agency for Cultural Affairs designates main halls (honden), oratories (haiden), gates, offering halls (heiden), purification halls (haraedono) and other structures associated with shrines as National Treasures in the category "shrines" (神社, jinja). Presently there are 37 National Treasures in this category, covering the time from 12th century (late Heian period) to 19th century (late Edo period). About half of the designated structures are located in three prefectures: Kyoto, Nara and Shiga in the Kansai region of Japan.

Temples

Structures associated with Buddhist temples such as main halls (butsuden, hon-dō and kon-dō), pagodas, belfries, corridors and other halls or structures are designated in the category "temples" (寺院, jiin). At present there are 152 National Treasures in this category, including some of the oldest wooden structures in the world from the 6th century at Hōryū-ji and Tōdai-ji's Daibutsuden, the largest wooden building in the world. The structures listed cover more than 1000 years of Japanese Buddhist architecture, from 6th century (Asuka period) to 19th century late Edo period. Most of the designated properties are located in the Kansai region with 60 National Treasure temple structures in Nara prefecture and 29 in Kyoto prefecture. At 18 structures, Hōryū-ji is the temple with most National Treasures.

Miscellaneous structures

There are three "miscellaneous structures" (その他, sono hoka) that do not fall in any of the other categories. They are the North Noh stage in Kyoto's Nishi Hongan-ji, the auditorium of the former Shizutani School in Bizen and the Roman catholic Ōura Church in Nagasaki dating to 1581, 1701 and 1864 respectively.

Fine arts and crafts

A total of 864 fine arts and crafts cultural properties have been designated as National Treasure in one of seven categories.

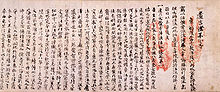

Ancient documents

Valuable Japanese historical documents are designated as National Treasure in the category "ancient documents" (古文書, komonjo). There are 59 items or sets of items in this category ranging from letters and diaries to records. One National Treasure is a linen map and one is an inscription on stone. Most objects however were created with a writing brush on paper and in many cases present important examples of calligraphy. The oldest item is from the late 7th century and the youngest from 19th century late Edo period.

Archaeological materials

Some of the oldest cultural properties are found in the category "archaeological materials" (考古資料, kōkoshiryō). There are presently 44 designated National Treasures. Many of these National Treasures denote large sets of various objects that were buried as part of graves or as offering for temple foundations and subsequently excavated from tombs, kofun, sutra mounds, or other archaeological sites. The oldest items are dogū clay figurines from the Jōmon period presenting some of the earliest signs of civilization in Japan. Other items listed include bronze mirrors and bells, jewelry, ancient swords, and knives. The youngest object, a hexagonal stone column, dates to the Nanboku-chō period, 1361. Most of the materials (27) are located in museums with seven National Treasures in the Tokyo National Museum.

Crafts

There are 252 National Treasures in the category "crafts" (工芸品, kōgeihin) including 122 swords and 130 other non-sword craft items.

- Swords

There are 122 swords and sword mounting National Treasures. The oldest designated properties date to the 7th century Asuka period. Most of the items are however from the Kamakura period and the youngest object is from the Muromachi period. The designated items are located in Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, museums or in private hand.

- Non-swords

Designated non-sword craft properties are Japanese, Chinese and Korean pottery, metalworks such as mirrors, temple bells, Buddhist ritual items and others; lacquerware such as boxes, furniture, harnesses and portable shrines; textiles, armour and other objects. These items cover the time from classical to early modern Japan from 7th century Asuka period to 18th century Edo period. They are located in Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines or museums. Also included in this category are sacred treasures which were presented by worshippers to Asuka Shrine, Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, Itsukushima Shrine, Kasuga-taisha and Kumano Hayatama Taisha. These treasures were dedicated to the enshrined deity of the respective shrine. They comprise garments, household and other items.

Historical materials

Large sets of historical materials are catalogued in the category "historical materials" (歴史資料, rekishi shiryō). Presently there are two National Treasure sets listed. One consists of more than 1000 documents and craft items related to the Shō family, the kings of Ryūkyū. The items date to between the 16th and 19th century and are located in the Naha City Museum of History.

The second set comprises religious and portrait paintings, documents, ceremonial tools, harnesses and items of clothing that were brought back by Hasekura Tsunenaga from his 1613 to 1620 trade mission (Keichō Embassy) to Europe. In total there are 47 objects which are located in the Sendai City Museum.

Paintings

Japanese and Chinese paintings from the 8th-century Classical Nara period to the early modern 19th-century Edo period are listed in the category "paintings" (絵画, kaiga). There are 158 National Treasures in this category showing Buddhist themes, landscapes, portraits and court scenes. Various base materials have been used: 90 are hanging scrolls; 38 are hand scrolls or emakimono; 20 are byōbu folding screens or paintings on sliding doors (fusuma); and three are albums. They are located in museums, Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, private collections, a university and one is located in a tomb (Takamatsuzuka Tomb). A large proportion of items are housed in the national museums of Tokyo, Kyoto and Nara. The greatest number of National Treasure paintings are located in Kyoto with 50, and Tokyo with 45, and more than half of the Tokyo paintings are located in the Tokyo National Museum.

Sculptures

Sculptures of Buddhist and Shintō deities or of priests venerated as founders of temple are listed in the category "sculptures" (彫刻, chōkoku). There are 126 National Treasure sculptures or groups of sculptures from the 7th-century Asuka period to the 13th-century Kamakura period. Most sculptures are wooden, 11 entries in the list are bronze, 11 are lacquer, 7 are made of clay and 1 entry, the Usuki Stone Buddhas, is a group of stone sculptures. The statues vary in size from just 10 cm (3.9 in) to 13 m (43 ft) and 15 m (49 ft) for the Great Buddhas of Nara and Kamakura. 70 of the 126 entries are located in Nara prefecture while another 37 are in Kyoto prefecture. With few exceptions, the sculptures are located in Buddhist temples. Hōryū-ji and Kōfuku-ji are the locations with the most entries, at 17 each. The Ōkura Shūkokan Museum of Fine Arts in Tokyo, the Nara National Museum in Nara and the Yoshino Mikumari Shrine in Yoshino, Nara have one National Treasure sculpture each; one National Treasure made up of four sculptures of Shinto gods is located at Kumano Hayatama Taisha and the Usuki Stone Buddhas belong to Usuki city.

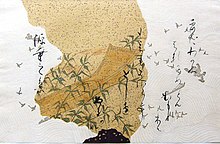

Writings

Written materials of various type such as sūtra transcriptions, poetry, historical and specialist books are designated in the category "writings" (書跡・典籍, shoseki, tenseki). 223 items or sets of items are National Treasures dating predominantly to classical Japan and the Imperial era of China from the 6th century to the Muromachi period. Most were made with a writing brush on paper and in many cases present important examples of calligraphy.

History

Background

Most cultural properties in Japan used to belong to Buddhist temples or Shinto shrines, or were handed down in aristocratic and samurai families.[3] Feudal Japan came to an abrupt end in 1867/68 when the Tokugawa shogunate was replaced by a new system of government in the Meiji Restoration.[4] Triggered by the official policy of separation of Shinto and Buddhism and anti-Buddhist movements that propagated the return to Shinto, a large number of Buddhist buildings and artwork were destroyed in an event known as haibutsu kishaku (literally "abolish Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni").[4][5][6] In 1871 the government confiscated the lands of temples, which were seen as a symbol of the previous ruling elite, and expropriated the properties of the feudal lords, causing the loss of historic castles and residences.[4][6][4] It is estimated that nearly 18,000 temples closed during this time.[6] Another factor that had a big influence on the cultural heritage was the increased industrialization and westernization, which accompanied the restoration and led to the impoverishment of Buddhist and Shinto institutions, the decay of temples and the export of valuable objects.[7][8][9]

1871 Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artifacts

On recommendation of universities, in 1871 the Daijō-kan issued a decree for the protection of antiquities, the Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artifacts (古器旧物保存方, koki kyūbutsu hozonkata), ordering prefectures, temples and shrines to compile lists of suitable important buildings and art treasures.[9][4] However, in the face of radical westernization, these efforts grounded to halt.[9] Starting in 1880 the government allotted funds for the preservation of ancient shrines and temples.[nb 1][7][4][4] By 1894, 539 shrines and temples had received subsidies for repairs and reconstruction[4][10][8] Buildings that were repaired during this period include the five-storied pagoda of Daigo-ji, the kon-dō of Tōshōdai-ji and the hon-dō of Kiyomizudera.[9] In a survey carried out under guidance of Okakura Kakuzō and Ernest Fenollosa from 1888 to 1897 all over Japan about 210,000 objects of artistic or historic merit were evaluated and catalogued.[4][8] The end of the 19th century saw a change in political climate and cultural values in the Japanese society: from an enthusiastic adoption of western values to a returned interest in the Japanese cultural heritage. Japanese architectural history appeared on curricula and the first books on architectural history were published, stimulated by the compiled inventories.[4]

1897 Ancient Temples and Shrines Preservation Law

On June 5, 1897, the government enacted the Ancient Temples and Shrines Preservation Law (古社寺保存法, koshaji hozonhō) (law number 49), which was the first systematic law for the preservation of Japanese historic art and architecture.[9][4] This law was formulated under the guidance of the architectural historian and architect Itō Chūta and established in 20 articles a system of government financial support for the preservation of buildings and the restoration of artworks.[9] It applied to works of architecture and related art of historic uniqueness and exceptional quality (art. 2).[9] Applications for financial support were to be made to the Ministry of Internal Affairs (art. 1), and the responsibility for restoration or preservation lay in the hand of local officials (art. 3). Restoration works were financed directly from the national coffers (art. 8).

This first law was followed by a second law on December 15, 1897 giving supplementary provisions for designating works of art in the possession of temples or shrines as "National Treasure" (国宝, kokuhō); religious architecture could be designated as "Specially Protected Building" (特別保護建造物, tokubetsu hogo kenzōbutsu).[4][11] The main criteria for designation were "artistic superiority" and "value as historical evidence and wealth of historical associations", but also age was considered in the designation.[2] Designated artworks could be from any of the following categories: painting, sculpture, calligraphy, books and handicrafts; subsequently swords were added. However the law was limited to items held by religious institutions, leaving privately owned articles unprotected.[12] Funds for the restoration of certain works of art and structures were raised from 20,000 yen to 150,000 yen and fines were set for the destruction of cultural properties. Owners had to register designated objects with newly created museums, which were granted first option in case of sale.[4] Initially, 44 temple and shrine buildings and 155 relics were thus designated, including the kon-dō at Hōryū-ji.[4][12]

The laws of 1897 are the foundation for today's preservation law.[11] At the time of their enactment only England, France, Greece and four other European nations had similar legislation in place.[5] The restoration of Tōdai-ji's Daibutsuden from 1906 to 1913 was carried out under these laws.[11] In 1914 the administration of cultural properties was transferred from the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Ministry of Education (today MEXT).[13]

1919 Historical Sites, Places of Scenic Beauty, and Natural Monuments Preservation Law

At the beginning of the 20th century, modernization transformed the landscape and posed a threat to historic and natural monuments. Societies of prominent men like the "Imperial Ancient Sites Survey Society" or the "Society for the Investigation and Preservation of Historic Sites and Aged Trees" lobbied and achieved a resolution in the House of Peers for conservation measures. Eventually, this led to the 1919 Historical Sites, Places of Scenic Beauty, and Natural Monuments Preservation Law (史蹟名勝天然紀念物保存法, shiseki meishō enrenkinenbutsu hozonhō), giving the same protection and cataloging to these properties as temples, shrines and pieces of art had received in 1897.[8]

1929 National Treasures Preservation Law

By 1929 about 1100 properties had been designated under the "Ancient Shrines and Temples Preservation Law" from 1897.[2] Most of these were religious buildings erected from the 7th to early 17th century. About 500 buildings had been extensively restored with 90% of costs paid from the national budget. Restorations during the Meiji period often employed new materials and techniques.[4]

In 1929, the National Treasures Preservation Law (国宝保存法, kokuhō hozonhō) was passed and came into force on July 1 of the same year. This law replaced the laws from 1897 extending the protection to all public and private institutions and private individuals in order to prevent the export or removal of cultural properties.[12][10] The focus was extended from religious buildings to castles, teahouses, residences and more recent religious buildings. Many of these structures had been transferred from feudal to private owners following the Meiji restoration. Some of the first residential buildings designated would be the Yoshimura residence in Osaka (1937) and the Ogawa residence in Kyoto (1944).[4] In addition the designation "National Treasure" was applied not only to objects of art but to historical buildings as well.[14][2][4] The new law also required permissions for intended alterations of designated properties.[4]

Starting with the restoration of Tōdai-ji's Nandaimon gate in 1930, the standards for preservation works were raised. An architect supervised the reconstruction works on-site and extensive restoration reports, including plans, results of surveys, historical sources and documentation of the work done, became the norm.[4] During the 1930s about 70–75 percent of restoration costs came from the national budget, which increased even during the war.[4]

1933 Law Regarding the Preservation of Important Works of Fine Arts

In the early 1930s Japan suffered from the Great Depression. In order to prevent art objects that had not been designated from being exported due to the economic crisis, the Law Regarding the Preservation of Important Works of Fine Arts (重要美術品等ノ保存ニ関スル法律, jūyō bijutsuhin tōno hozon ni kan suru hōritsu) was passed on April 1, 1933. It provided for a simpler designation procedure and temporary protection that included export. About 8000 objects were protected under this law including temples, shrines and residential buildings.[4] By 1939 8,282 items in nine categories (painting, sculpture, architecture, documents, books, calligraphy, swords, crafts and archaeological resources) had been designated as National Treasure and were forbidden to be exported.[12]

During World War II many of the designated bulidings were camouflaged, and water tanks and fire walls installed for protection. 206 designated buildings, including Hiroshima Castle, were destroyed from May to August 1945.[4] The 9th century Buddhist text Tōdaiji Fujumonkō, designated as National Treasure in 1938 was destroyed in 1945 by fire as a result of the war.[15]

Present 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties

On January 26, 1949, the kon-dō of Hōryū-ji, one of the oldest extant wooden buildings in the world and the first to be protected under the "Ancient Temples and Shrines Preservation Law", caught fire, resulting in the serious damage of valuable 7th century wall paintings. This incident accelerated the reorganisation of cultural property protection and gave rise to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties (文化財保護法, bunkazai hogohō) which was drafted on May 30, 1950 and came into force on August 29 of the same year.[14][18][13][3] The new law combined the laws of 1919, 1929 and 1933, expanding their scope to cover also "intangible cultural properties" such as performing and applied arts, "folk cultural properties" and "buried cultural properties".[14][18] Before the enactment of this law only intangible cultural properties of especially high value at risk of extinction had been protected.[3][14][2] Even by international standards a broad spectrum of properties was covered by the 1950 law.[14] The law was the basis for the establishment of the Committee for the Protection of Cultural Properties, a precursor of today's Agency for Cultural Affairs.[19] It allowed the selection of the most important cultural properties, set restrictions on the alteration, repair and export of cultural properties and provided measures for the preservation and utilization of such properties.[20]

The regulations implementing the law specified three broad categories of properties: tangible/intangible cultural properties and "historic sites, places of scenic beauty, natural monuments".[14][19] Tangible cultural properties were in this context defined as objects of "high artistic or historic value" or archaeological materials (or other historic material) of "high scholarly value".[14] Designated buildings were required to be outstanding in design or building technique, having a high historic or scholarly value or being typical of a movement or area.[14]

A two tier system for tangible cultural properties was established with the gradings: Important Cultural Property and National Treasure.[14][18] The minister of education can designate important cultural properties as National Treasures if they are of "particularly high value from the standpoint of world culture or outstanding treasures for the Japanese people".[14] All previously designated National Treasures were initially demoted to important cultural properties. Some of them have been designated as new "National Treasures" since June 9, 1951.[14] Following a decision by the National Diet, properties to be nominated as World Heritage Site are required to be protected under the 1950 law.[21]

Extensions of the law since 1950

National Treasures have been designated according to the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties starting from June 9, 1951.[14] This law, which retains its validity, has since been supplemented with amendments and additional laws, re-organizing the system for protection and preservation or extending its scope to a larger variety of cultural properties. Some of these changes affected indirectly the protection of designated National Treasures.

Particularly in the 1960s, the spectrum of protected buildings was expanded to include early examples of western architecture.[14] In 1966 the Law for the Preservation of Ancient Capitals was passed. It was restricted to the ancient capitals of Kamakura, Heijō-kyō (Nara), Heian-kyō (Kyoto), Asuka, Yamato (present day Asuka, Nara), Fujiwara-kyō (Kashihara), Tenri, Sakurai and Ikaruga, places with a large number of National Treasures.[10][10][21] This law was extended in 1975 to groups of historic buildings, not necessarily located in capitals.[22][2][18][21]

As a second major change of 1975, the government started to protect not only tangible or intangible properties for their historic or artistic value directly but also the techniques for the conservation of cultural properties.[22] This step was made necessary by the disappearance of skilled craftsmen as a result of the industrialization.[22] The techniques protected applied to tangible and intangible cultural properties and included the mounting of paintings and calligraphy on scrolls, the repair of lacquerware and wooden sculptures, and the production of Noh masks, costumes and instruments.[22][18]

The two-tier system of "National Treasures" and "Important Cultural Properties" was supplemented in 1996 with a new level Registered Cultural Property for items in great need of preservation and use, initially limited to buildings and acting as a waiting list for the list of nominated Important Cultural Properties and thereby for National Treasures.[18] A large number of mainly industrial and historic residencees from the late Edo to the Shōwa period were registered under this system.[23] Compared to important cultural properties and National Treasures, registration entails fewer responsibilities for the owner.[23] Since the end of the 20th century, the Agency for Cultural Affairs has been focusing on the designation of structures built between 1868 and 1930 or those in underrepresented regions.[14] The insufficient supply of raw materials and tools necessary for restoration works was realized by the agency.[22] In 1999 the protective authority was transferred to prefectures and designated cities.[18]

Designation procedure

Cultural products with a tangible form that possess high historic, artistic, and academic value for Japan are listed in a three-tier system. Properties that are in great need for preservation and use are cataloged as "Registered Cultural Properties".[nb 2][20] Important objects are designated as "Important Cultural Properties".[3]

Important cultural properties that show truly exceptional workmanship, a particularly high value for the world cultural history or an exceptional value to scholarship can be designated as "National Treasure".[12][20] In order to achieve designation, the owner of an important cultural property contacts or is contacted by the Agency for Cultural Affairs to exchange advice and information regarding the registration.[13] In the latter case, the agency always asks the owner for consent beforehand, even though this is not required by law.[nb 3][14] The agency then contacts the Council for Cultural Affairs, which consists of five members appointed by the minister of education for their "wide and eminent views on and knowledge of culture". The council may seek support from an investigative commission, and eventually prepares a report to the Agency for Cultural Affairs. If they support the nomination, the property is placed on the registration list of cultural properties, the owner is informed of the outcome and an announcement is made in the official gazette.[18][13][20][14] The designation policy is deliberately restrained, keeping the number of designated properties low.[24]In this respect the South Korean protective system is similar to that of Japan.[25] In the 21st century between one and five properties were designated every year.[26]

Preservation and utilization measures

To guarantee the preservation and utilization of designated National Treasures, a set of measures was laid down in the "Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties" from 1950. These direct measures are supplemented by indirect efforts aimed at protecting the built environment (in the case of architecture) or techniques necessary for restoration works.[nb 4][18]

Owners or managers of National Treasures are responsible for administration and restoration works.[20] They are required to consult the Agency for Cultural affairs in case of loss, destruction, damage, alteration, change in location or transfer of ownership of the cultural property.[13][20] Any changes require a permit and the agency is to be notified of repairs at least 30 days before (§ 43)[14][20][18]. On request, owners have to supply information and report to the commissioner of the agency for cultural affairs on the condition of the property (§ 54).[14] If a National Treasure is damaged, the commissioner can order the owner or custodian to carry out repairs and can in case of non-compliance carry out repairs himself.[nb 5] In case of sale of a National Treasure, the government has the first option to buy the item (§ 46).[14][27] National treasures are generally more restricted in transfer and may not be exported.[24]

The commissioner can recommend public access to the property and, if subsidies were granted, he can order public access or loan to a museum for a limited period of time (§ 51).[14][27][20] The requirement of public access which for private owners means ceding certain rights, has been suggested as one of the reasons that, with the exception of the Shōsōin, none of the properties under supervision of the Imperial Household Agency has been designated as National Treasure.[25] The agency holds the view that their properties are sufficiently protected and do not need any protection under the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties.[14] Through documentation and the establishment and operation of museums and centres for cultural research, the government satisfies public and scientific interest in cultural properties.[18]

Measures are not limited to responsibilities for owners. Apart from the prestige gained through the designation, owners are entitled to local tax exemption including fixed assets tax, special property tax, and city planning tax. National taxes applying to the transfer of properties are also reduced.[28][20][18]

The Agency for Cultural Affairs provides owners or custodians with advise and guidance on matters of administration, restoration and the public display of National Treasures.[20][13] Besides this, the agency promotes local activities that are aimed at the protection of cultural properties, such as activities for the study, protection, or transmission of cultural properties.[20]

Not least, the government provides grants for repairs, maintenance and the installation of fire-prevention facilities and other disaster prevention systems.[20] Subsidies to municipalities to purchase land or cultural property structures are also available.[18] Designated properties generally become more valuable.[20][13][27] The budget allocated by the Agency for Cultural Affairs in fiscal 2009 for the "Facilitation of Preservation Projects for National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties" amounted to 12,013 million yen or 11.8% of the total budget of the agency. Enhancements of Cultural Properties Protection which include the former contingent were allocated 62,219 million yen or 61.0%.[28]

Only if the owner cannot be located or damages or fails to adequately protect the designated property or is unwilling to cooperate for public access does the government have the right to name a custodian which is usually a local governing body.[27]

Statistics

The Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan publishes the list of National Treasures and other designated Japanese cultural artifacts at the Database of National Cultural Properties.[26] As of December 1, 2009, there are 864 National Treasures in the arts and crafts category and 215 in the buildings and structures category. The total number of arts and crafts items as well as the total number of structures is actually higher since related objects are sometimes joined under a common name.

Geographical distribution

This table shows the number of National Treasures in each prefecture grouped by type of the property. Gold colored cells mark prefectures with the largest number of National Treasures for the given category (column).

| Prefecture | National Treasures | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine arts and crafts | Buildings and structures | Total | |||||||||||||

| Ancient documents | Archaeol. materials | Crafts | Historical materials | Paintings | Sculptures | Writings | Sum | Castles | Resid. | Shrines | Temples | Misc. struct. | Sum | ||

| Aichi | -

|

-

|

9 | -

|

2 | -

|

4 | 15 | 1 | 1 | -

|

1 | -

|

3 | 18 |

| Akita | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 1 |

| Aomori | -

|

1 | 2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

3 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 3 |

| Chiba | 2 | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

5 | 8 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 8 |

| Ehime | -

|

1 | 8 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

9 | -

|

-

|

-

|

3 | -

|

3 | 12 |

| Fukui | -

|

-

|

3 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | 4 | -

|

-

|

-

|

2 | -

|

2 | 6 |

| Fukuoka | 1 | 6 | 6 | -

|

2 | -

|

2 | 17 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 17 |

| Fukushima | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1 | 1 | 2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 3 |

| Gifu | 1 | -

|

2 | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

4 | -

|

-

|

-

|

3 | -

|

3 | 7 |

| Gunma | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 0 |

| Hiroshima | -

|

-

|

14 | -

|

2 | -

|

1 | 17 | -

|

-

|

1 | 6 | -

|

7 | 24 |

| Hokkaido | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 1 |

| Hyōgo | -

|

1 | 2 | -

|

2 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 5 | -

|

-

|

6 | -

|

11 | 20 |

| Ibaraki | -

|

-

|

2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 2 |

| Ishikawa | -

|

-

|

2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 2 |

| Iwate | -

|

-

|

4 | -

|

1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 8 |

| Kagawa | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

3 | 4 | -

|

-

|

1 | 1 | -

|

2 | 6 |

| Kagoshima | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 1 |

| Kanagawa | -

|

-

|

6 | -

|

6 | 1 | 4 | 17 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 18 |

| Kōchi | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | 2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 3 |

| Kumamoto | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

1 | 1 |

| Kyoto | 29 | 4 | 17 | -

|

52 | 37 | 67 | 206 | -

|

11 | 7 | 29 | 1 | 48 | 254 |

| Mie | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

3 | 4 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 4 |

| Miyagi | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

2 | 3 | -

|

-

|

1 | 2 | -

|

3 | 6 |

| Miyazaki | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 0 |

| Nagano | -

|

1 | 1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

2 | 1 | -

|

1 | 3 | -

|

5 | 7 |

| Nagasaki | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | -

|

-

|

-

|

2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Nara | 2 | 7 | 38 | -

|

17 | 70 | 15 | 149 | -

|

-

|

4 | 60 | -

|

64 | 213 |

| Niigata | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 1 |

| Ōita | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

2 | -

|

-

|

1 | 1 | -

|

2 | 4 |

| Okayama | -

|

-

|

5 | -

|

2 | -

|

-

|

7 | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 2 | 9 |

| Okinawa | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 1 |

| Osaka | 2 | 3 | 22 | -

|

6 | 4 | 14 | 51 | -

|

-

|

2 | 3 | -

|

5 | 56 |

| Saga | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1 | 1 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 1 |

| Saitama | -

|

1 | 2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | 4 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 4 |

| Shiga | 8 | 1 | 5 | -

|

4 | 4 | 12 | 34 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 12 | -

|

22 | 56 |

| Shimane | -

|

2 | 2 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

4 | -

|

-

|

2 | -

|

-

|

2 | 6 |

| Shizuoka | 1 | -

|

7 | -

|

1 | -

|

2 | 11 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 11 |

| Tochigi | 1 | -

|

4 | -

|

-

|

-

|

5 | 10 | -

|

-

|

6 | -

|

-

|

6 | 16 |

| Tokushima | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | 0 |

| Tokyo | 10 | 12 | 74 | -

|

46 | 1 | 64 | 207 | -

|

1 | -

|

1 | -

|

2 | 209 |

| Tottori | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

2 | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

-

|

1 | 3 |

| Toyama | -

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

0 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 1 |

| Wakayama | 1 | -

|

3 | -

|

9 | 5 | 9 | 27 | -

|

-

|

-

|

7 | -

|

7 | 34 |

| Yamagata | 1 | -

|

2 | -

|

1 | -

|

-

|

4 | -

|

-

|

-

|

1 | -

|

1 | 5 |

| Yamaguchi | -

|

-

|

3 | -

|

1 | -

|

2 | 6 | -

|

-

|

1 | 2 | -

|

3 | 9 |

| Yamanashi | -

|

-

|

1 | -

|

2 | -

|

-

|

3 | -

|

-

|

-

|

2 | -

|

2 | 5 |

| Sum | 59 | 44 | 252 | 2 | 158 | 126 | 223 | 864 | 8 | 15 | 37 | 152 | 3 | 215 | 1079 |

The geographical distribution of National Treasures in Japan is highly uneven. Remote areas like Hokkaido or Kyushu have very few designated properties and in most prefectures there are only a couple of National Treasure structures. Three prefectures, Gunma, Miyazaki and Tokushima do not have any National Treasures.

Four prefectures in the Kansai region of central Honshū out of the forty Japanese prefectures boast each more than ten National Treasure structures: Hyōgo (11), Kyoto (48), Nara Prefecture (64) and Shiga Prefecture (22). Together they comprise 145 or 67.5% of all structural National Treasures in Japan. Three sites, Kyoto, capital and seat of the imperial court for more than 1000 years, Hōryū-ji founded by Prince Shotoku around 600 and Nara, capital of Japan from 710 to 784, together have 90 structural National Treasures.

Fine arts and crafts National Treasures are distributed in a similar fashion to the designated structures with remote areas having few National Treasures and a high concentration in the Kansai region. The seven prefectures of that area harbor 480 or 55.5% of all arts and crafts National Treasures. Tokyo, which has only two National Treasure buildings, has an exceptionally high number of cultural properties in this category. Out of the 207 properties located in Tokyo, 87 are at the Tokyo National Museum.[29]

Types of National Treasures

About 89% of structural National Treasures are religious in nature. Residences account for 8% of all designated buildings and the rest is shared among castles and miscellaneous structures. More than 90% are wooden buildings and about 13% of designated buildings are in private ownership.

In "fine arts and crafts", more than 30% of National Treasures are written materials such as documents, letters or books. Swords, paintings, sculptures and non-sword craft items each account for about 15% of National Treasures in this category.

Age of National Treasures

With some of the oldest archaeological National Treasures older than 10,000 years and the Akasaka Palace dating to the early 20th century, the designated items provide an exemplary overview about the history of Japanese art and architecture from ancient to modern times. Items from any of the categories of National Treasures do not cover this whole interval of time, but generally only a short period of time which is often determined by historical events and sometimes coincides with the time in which this specific artistry or type of architecture flourished.

Temple National Treasures cover the time from around the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the mid-6th century to 19th century early modern Japan. The history of Shinto shrines in Japan is even older than that of temples. However, due to the tradition of rebuilding shrines at regular intervals, known as Shikinen sengū-sai (式年遷宮祭), the oldest designated shrine structures date to the late 12th century. The archetypical Japanese castles are a product of a period of 50 years starting with the construction of Azuchi Castle in 1576 which marked a change in style and function of castles. Castle construction ends around 1620 when the Tokugawa shogunate, after having destroyed the Toyotomi clan in 1615, prohibits the building of new castles.

In Japan the first signs of stable living patterns and civilization date to the Jōmon period from about 14,000 BC to 300 BC. Clay figurines (dogū) and some of the world's oldest pottery discovered at sites in northern Japan have been designated as the oldest National Treasures in the category "archaeological materials". Some of the youngest items in this category are objects discovered in sutra mounds from the Kamakura period.

The starting date of designated "crafts", "writings" and "sculptures" is connected to the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in 552. In fact some of the oldest designated National Treasures of these categories were directly imported from mainland China and Korea. After the Kamakura period, the art of Japanese sculpture which had been mainly religious in nature deteriorated. Consequently there are no National Treasure sculptures from after the Kamakura period.

Notes

- ^ In connection with the establishment of "State Shinto", shrines had received annual funds since 1874.

- ^ This applies primarily to works of the modern period like houses, public structures, bridges, dikes, fences, and towers, threatened by land development and changes in lifestyle. Registration is meant to prevent their demolition without evaluation of their cultural value. Protection measures are moderate and include notification, guidance and suggestions. As of April 1, 2009, there are 7407 registered structures.

- ^ It is usually difficult to obtain the consent from state properties and private firms.

- ^ These supplemental measures were added as amendments to the 1950 "Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties".

- ^ For important cultural properties, the commissioner has only the right to recommend repairs.

References

- ^ Hickman 2002, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f Jokilehto 2002, p. 280

- ^ a b c d e Agency for Cultural Affairs (ed.). "Intangible Cultural Heritage" (PDF). Administration of Cultural Affairs in Japan ― Fiscal 2009. Asia/Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU). Cite error: The named reference "pamphlet05" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Enders & Gutschow 1998, p. 12

- ^ a b Robertson 2005, p. 38

- ^ a b c Gibbon 2005, p. 331

- ^ a b Jokilehto 2002, p. 279

- ^ a b c d Robertson 2005, p. 39

- ^ a b c d e f g Coaldrake 2002, p. 248

- ^ a b c d Issarathumnoon, Wimonrart (2003–2004). "The Machizukuri bottom-up approach to conservation of historic communities: lessons for Thailand" (PDF). The Nippon Foundation. Urban Design Lab, Tokyo University.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c Coaldrake 2002, p. 249

- ^ a b c d e Mackay-Smith, Alexander (2000-04-29). "Mission to preserve and protect". Japan Times. Tokyo: Japan Times Ltd. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gibbon 2005, p. 332

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Enders & Gutschow 1998, p. 13

- ^ Yoshida 2001, p. 135

- ^ "金堂" (in Japanese). Hōryū-ji. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ "五重塔" (in Japanese). Hōryū-ji. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Cultural Properties for Future Generations" (PDF). Administration of Cultural Affairs in Japan ― Fiscal 2009. Agency for Cultural Affairs. 2007-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b McVeigh 2004, p. 171

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Preservation and Utilization of Cultural Properties" (PDF). Administration of Cultural Affairs in Japan ― Fiscal 2009. Agency for Cultural Affairs. 2009.

- ^ a b c Nobuko, Inaba (1998). "Policy and System of Urban / Territorial Conservation in Japan". Tokyo: Tokyo National Research Institute of Cultural Properties. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ a b c d e Enders & Gutschow 1998, p. 14

- ^ a b Enders & Gutschow 1998, p. 15

- ^ a b Gibbon 2005, p. 333

- ^ a b Gibbon 2005, p. 335

- ^ a b The Agency for Cultural Affairs (2008-11-01). "国指定文化財 データベース" (in Japanese). Database of National Cultural Properties. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ a b c d Gibbon 2005, p. 334

- ^ a b "Foundations for Cultural Administration" (PDF). Administration of Cultural Affairs in Japan ― Fiscal 2009. Agency for Cultural Affairs. 2003–2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "Frequently asked questions about the Tokyo National Museum". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

Bibliography

- Coaldrake, William Howard (2002) [1996]. Architecture and authority in Japan. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-05754-X. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Enders, Siegfried R. C. T.; Gutschow, Niels (1998). Hozon: architectural and urban conservation in Japan (illustrated ed.). Stuttgart/London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 3930698986.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Gibbon, Kate Fitz (2005). Who owns the past?: cultural policy, cultural property, and the law. Rutgers series on the public life of the arts (illustrated ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813536871.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hickman, Money L. (2002). Japan's Golden Age: Momoyama (illustrated ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300094078.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Jokilehto, Jukka (2002) [1999]. A history of architectural conservation. Butterworth-Heinemann series in conservation and museology, Conservation and Museology Series (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0750655119.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - McVeigh, Brian J. (2004). Nationalisms of Japan: managing and mystifying identity. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0742524558.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Robertson, Jennifer Ellen (2005). A companion to the anthropology of Japan. Blackwell Companions to Social and Cultural Anthropology (illustrated ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631229558.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Yoshida, Kanehiko (2001). Kuntengo Jiten (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Tōkyōdō Shuppan. ISBN 4-490-10570-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)